1. Introduction

Lung cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounting for approximately 85% of all lung cancer cases [

1]. For patients with early-stage NSCLC, surgical resection has always been considered the treatment of choice, offering the best chance for long-term survival [

2]. Traditionally, lobectomy has been the gold standard for the surgical management of this tumor [

3], but thanks to an attentive screening program, it has spread worldwide. To a more frequent identification of small lung tumors, the thoracic surgery community has been pushed into developing more and more less invasive and extensive resections.

In this setting, considering the latest publication of the JCOG0802 and CALGB 140503 trials, lung segmentectomy has been recently proven to be a valid alternative to lobectomy in selected patients with NSCLC < 2 cm, with acceptable long-term outcomes without significant functional impairment [

4,

5]

Furthermore, the minimally invasive approach has largely replaced open surgery for almost every elective procedure, and technological innovations and technical developments have provided a significant boost in this direction, ultimately enabling the use of robotic platforms worldwide. The robotic platform offers enhanced precision, superior dexterity, and three-dimensional visualization, potentially leading to better surgical outcomes compared to traditional thoracoscopic techniques [

6,

7], particularly in the case of sublobar resection [

8].

Robotic-assisted segmentectomy (RAS) is, in fact, a recent evolution in the field of minimally invasive thoracic surgery; however, despite its growing adoption, the long-term efficacy of RAS, particularly its oncologic outcomes, remains unclear.

This study aims to explore whether RAS can serve as an alternative to RAL in early-stage NSCLC, with a specific focus on long-term outcomes, including 10-year cancer-specific survival (CSS), cumulative rate of relapse (RR), and local recurrence (LR).

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of 1,040 patients who underwent robotic anatomical lung resection for early-stage NSCLC between August 2007 and August 2023 was performed at the European Institute of Oncology in Milan. Forty patients underwent RAS, and each patient was retrospectively matched with three patients undergoing RAL over the same period, by propensity score matching (1:3) based on demographic characteristics (age, sex), pathological features (tumor size and grade, histology, tumor site), and pathological stage, following 8th TNM staging system.

Inclusion criteria were: clinical stage IA and IB NSCLC (less than 4 cm in size, N0 and no evident pleural involvement) according to the 8th edition of the TNM staging system in lung cancer; intent-to-treat anatomical segmentectomy or lobectomy with radical lymphadenectomy, performed by robotic approach; no preoperative induction therapy; no previous history of concurrent malignant disease or other previous primary lung cancer. We excluded from the study all patients with one or more of the following conditions: histology other than NSCLC; incomplete preoperative staging; incomplete lymphadenectomy; or anatomical resection other than anatomical segmentectomy or lobectomy.

The decision to perform anatomical segmentectomy or lobectomy was based on the patient’s fitness for surgery (respiratory function, previous lung surgery) and the surgeon’s choice.

All segmentectomies were “simple” segmentectomy following the definition proposed by Handa et al [

9].

Data were collected retrospectively from patients’ medical records, including demographic information, operative details, postoperative outcomes, and long-term follow-up data.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (UID 4367) of our Institution, and all patients provided informed consent to undergo surgery and for their data to be used in research.

2.1. Preoperative Assessment

Preoperative staging was based on a total-body computed tomography scan (CT scan) and positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose (PET) scan. Whenever possible, suspected lymph node involvement was verified with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) or mediastinoscopy. Staging and functional exams were always performed within 5 weeks before surgery.

2.2. Surgical Procedures

All patients underwent segmentectomy or lobectomy via robotic approach along with systematic lymph node dissection, under general anesthesia and single-lung ventilation. The four-arm robotic approach, as described elsewhere [

10], was applied. Briefly, a 3-cm utility incision was made in the fourth or fifth intercostal space, anteriorly, along with three additional 8-mm ports: one for the camera in the seventh or eighth intercostal space along the mid-axillary line, and two others at the seventh or eighth intercostal space in the posterior axillary line and in the auscultatory triangle at the sixth intercostal space, respectively. Until 2015, da Vinci S and SI systems (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) were applied, whereas the da Vinci Xi system was introduced thereafter. Pulmonary arteries, veins, and bronchi were resected either with a mechanical stapler (EndoGIA 30 vascular and 30 or 45 parenchyma) or with a robotized stapler (EndoWrist 30 or 45 vascular and parenchyma). The segmental plane was completed with inflation of the lobe. Patients with N1 involvement or with positive margins on frozen section underwent lobectomy and were excluded from the analysis.

Operating time was measured from the first incision to the final closure of the wound.

2.3. Postoperative Follow-Up

Patients were followed with a physical examination, chest X-ray, and blood tests 1 month after surgery. Subsequent follow-up consisted of a physical exam plus chest and upper abdomen CT scans every 4 months for 3 years, then every 6 months until the fifth year, and annually thereafter.

Recurrences in the hilar/mediastinal nodal area or lung tissue near the previous resection were recorded as local. New pulmonary nodules or pleural lesions on the same or opposite side were classified as regional, while any lesions found outside the thoracic cavity were considered distant metastases.

Postoperative complications were defined as any complication occurring within 30 days after surgery and were categorized using the Thoracic Morbidity and Mortality classification system [

11]. Postoperative death was defined as mortality occurring within 30 days after surgery or during hospitalization.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Absence of normality was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test for all continuous variables considered in the analysis, which were described as median and range and compared using a non-parametric median test. Categorical data were expressed as numbers and frequencies and were compared using the Chi-squared test. CSS was defined as the time from the date of surgery to the date of death due to lung cancer; instead, relapse was defined as the occurrence of local, regional, or distant lesions related to the treated lung cancer. Deaths from unrelated causes were treated as competing events. Survival outcomes, including CSS and RR, were analyzed using the Kalbfeisch-Prentice method [

12], and compared by Gray’s test [

13]. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05. Analysis was performed using SAS software v. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States).

3. Results

Forty patients who underwent RAS and fulfilled the inclusion criteria were propensity score matched (1:3) with 120 patients undergoing RAL. The median age of patients in the RAS group was 64.5 years (range, 50–85 years), compared to 66 years (range, 43–83 years) in the RAL group (p = 0.69). In the RAS and RAL groups, 22 patients (55.0%) and 53 patients (44.2%), respectively, were male (p = 0.23).

In the segmentectomy group, 17 patients had S6 segmentectomy, 17 patients underwent apico-dorsal segmentectomy (left S1+S2+S3), three patients underwent lingulectomy (left S4+S5), and three patients had a right apico-ventral segmentectomy (right S1+S2).

Adenocarcinoma was the most common histology in both cohorts (87.5% and 87.5%, respectively; p = 1.00), and most tumors were graded as G2 (60.0% and 68.3%, respectively; p = 0.63). The median tumor size was 12.5 (6–34) mm in the RAS group, compared to 15 (6–32) mm in the RAL group (p = 0.64). The majority of tumors were at stage I of the disease in both groups (90.0% and 96.7%, respectively; p = 0.17).

The characteristics of patients, operative details, and pathological features for matched RAS and RAL cohorts are detailed in

Table 1.

Only one patient (2.5%) in the RAS group was converted to thoracotomy for pleural adhesions. In contrast, three patients (2.5%) in the RAL group were converted to open surgery (one for bleeding and two for pleural adhesions).

3.1. Short-Term Outcomes

The short-term outcomes of the matched RAS and RAL cohorts are presented in

Table 2.

The median operative time for RAS was 159 (95–224) minutes, which was slightly shorter but not statistically significant compared to the median operative time for RAL, 167 (70–348) minutes (p = 0.27). The median length of hospital stay was shorter in the RAS group, with a median of 4 days (range, 3–21 days), compared to 5 days (range, 3–35 days) in the RAL group (p = 0.10). Notably, none of the patients in the RAS cohort experienced a postoperative Intensive Care Unit (ICU) stay, whereas 15 (12.5%) patients in the RAL cohort did (p = 0.02). The 30-day mortality rate was 0% in both groups, with a 30-day morbidity rate of 25% in the RAS group and 23.3% in the RAL group (p = 0.83). In particular, into the RAS cohort, 2 (5.0%) patients experienced major complications such as severe pulmonary embolism in 1 case (grade IV) and sputum retention requiring bronchoscopy in another patient (grade IIIa); 8 (20.0%) patients experienced minor complications such as pulmonary atelectasis in 2 cases (grade I), wound hematoma in 1 case (grade II), pleural effusion in 1 patient (grade II), two atrial fibrillation (grade II), and 2 cases of prolonged air leak (grade II).

In terms of lymph node harvesting, the RAS group had significantly lower median numbers of N2 nodal stations sampled compared to the RAL group: 2 [0 - 5] and 3 [1 - 5], respectively, p= 0.0001), whereas the median number of N1 stations harvested was overlapping between the two groups (RAS 2 (0-4) vs. RAL 2 (0-5); p = 0.18). Additionally, the median number of lymph nodes retrieved was significantly lower in the RAS group compared to the RAL group, both in station N1 and N2 (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.06, respectively) (

Table 2).

3.2. Long-Term Outcomes

The overall median follow-up was 60 months [range 1 to 190]. In particular, the median follow-up for the RAS group was 118 months [range 6 to 190].

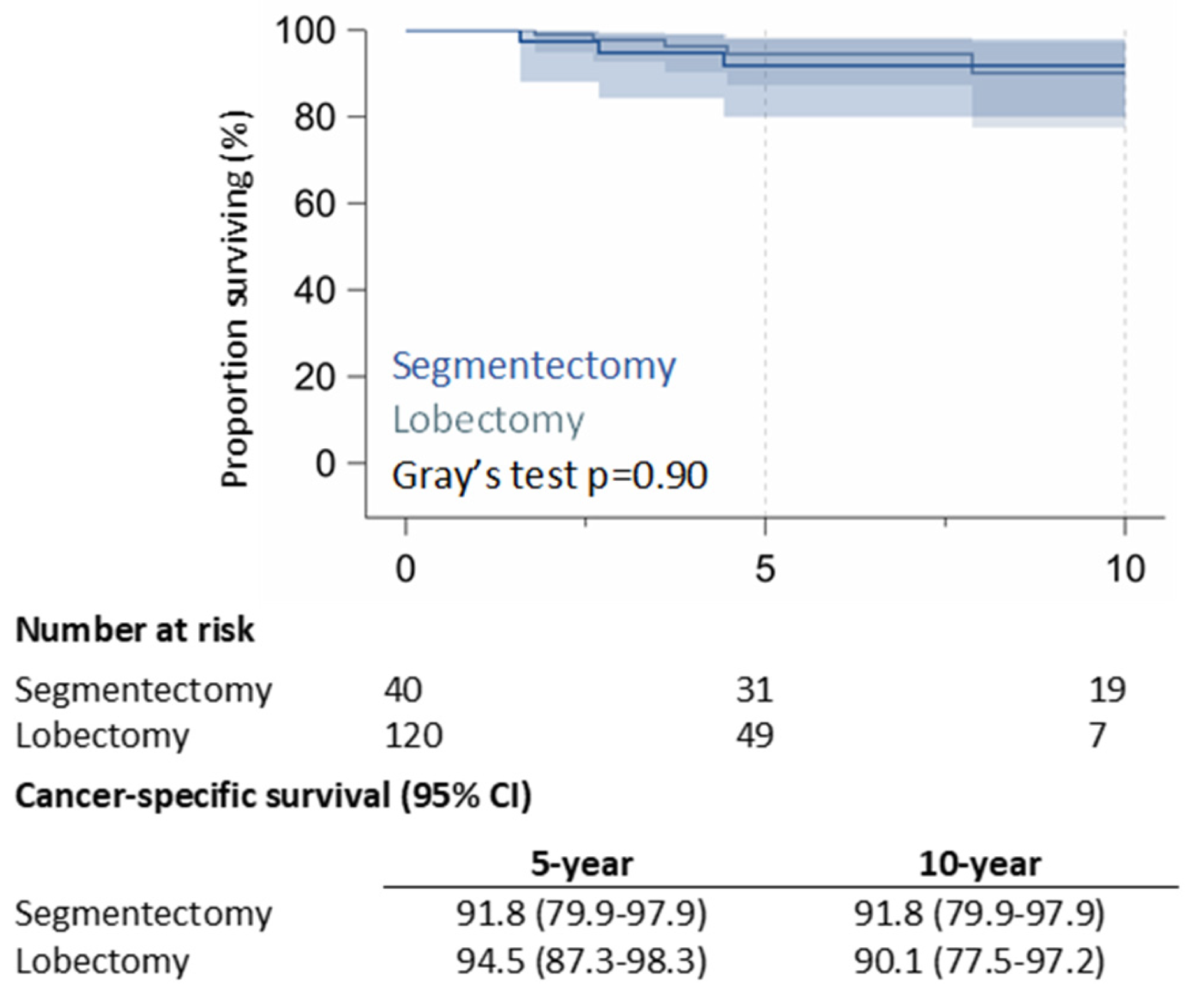

The 10-year CSS rate was 91.8% (95% CI: 79.9%–97.9%) in the RAS group and 90.1% (95% CI: 77.5%-97.2%) in the RAL group (p = 0.90) (

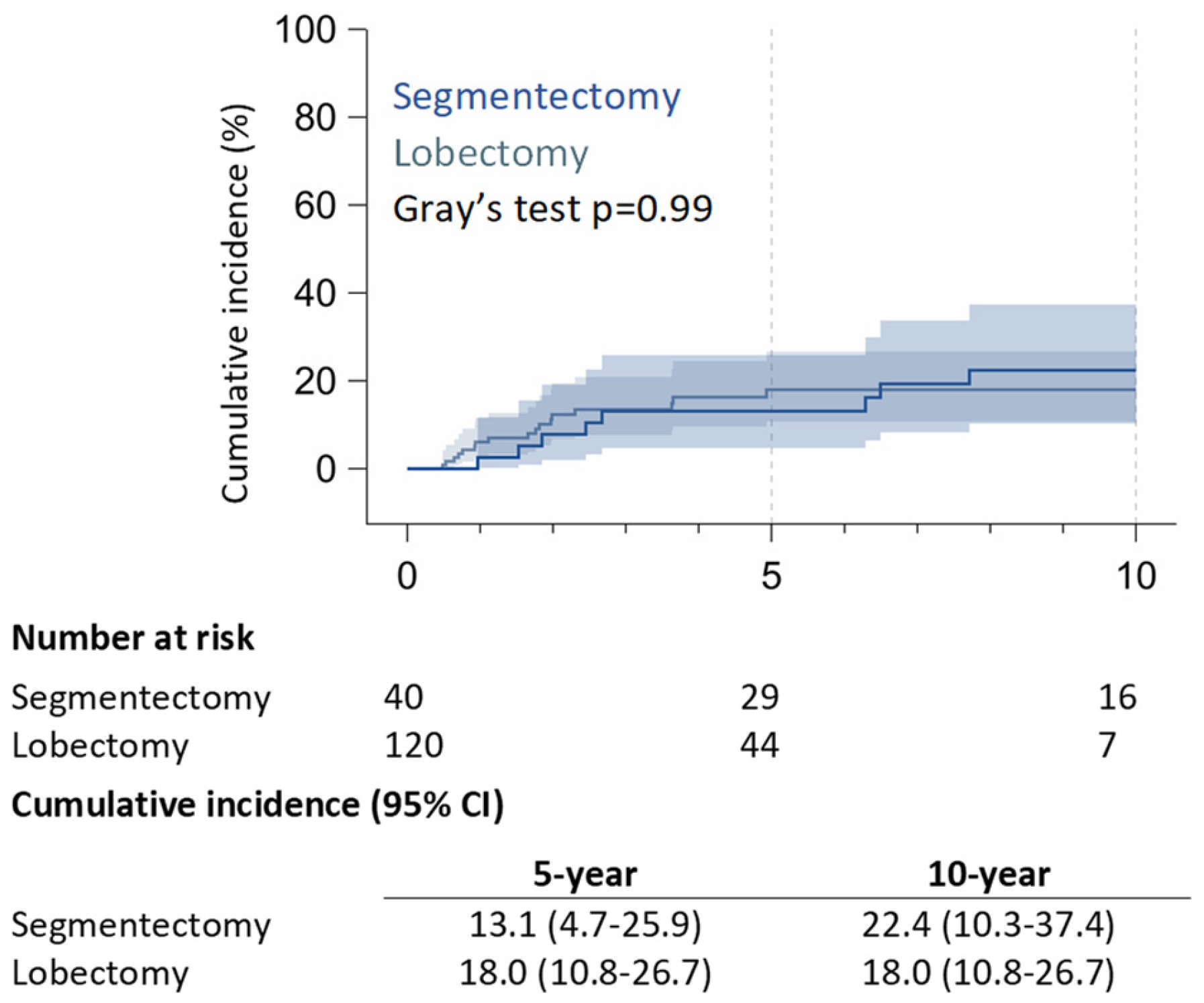

Figure 1). 5-year of RR was 13.1% (95% CI: 4.7% – 25.9%) in the RAS group and 18.0% (95% CI: 10.8% – 26.7%) in the RAL group; 10-year of RR was 22.4% (95% CI: 10.3% – 37.4%) for RAS patients, and 18.0% (95% CI: 10.8% – 26.7%) for RAL patients (p = 0.99) (

Figure 2).

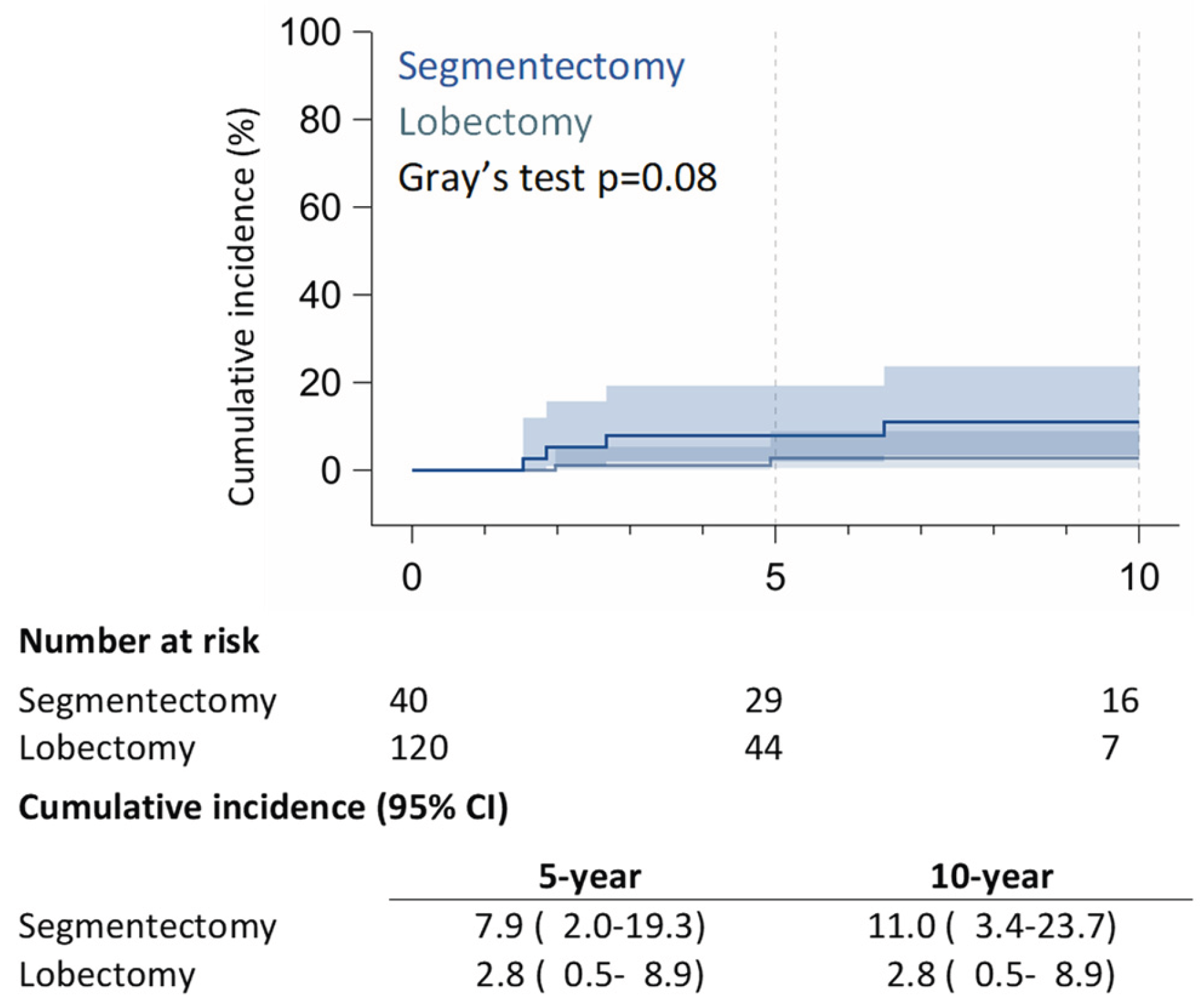

Within the RAS cohort, 8 (20%) patients had recurrences: 5 (12.5%) patients experienced local recurrences (LR) (4 on lung parenchyma and one on ipsilateral mediastinal nodes), 2 (5%) patients developed regional recurrence on contralateral lung parenchyma, and 1 (2.5%) patient developed distant recurrence on the bone. Within the RAL matched group, 17 (14.2%) patients experienced recurrences: 2 (1.7%) patients had local recurrence with hilar lymph node relapses, 8 (6.7%) patients presented regional recurrences (2 ipsilateral pleural lesions and six contralateral pulmonary nodules), and 7 (5.8%) patients had distant metastasis, mainly brain recurrences. 5-year of LR was 7.9% (95% CI: 2.0% – 19.3%) in the RAS group and 2.8% (95% CI: 0.5% – 8.9%) in the RAL group; 10-year of LR was 11.0% (95% CI: 3.4% – 23.7%) for RAS patients, and 2.8% (95% CI: 0.5% – 8.9%) for RAL patients (p = 0.08) (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

Lung segmentectomy has recently been proven to be a valid alternative to lobectomy in selected patients with NSCLC <2 cm [

4,

5]. In the early 2010s, the first reports of experiences in RAS appeared in the literature, yielding encouraging results [

14,

15]. Since then, several studies have consecutively demonstrated its safety and feasibility [

16,

17,

18,

19], which explains the increasing use of the robotic approach for segmentectomies [

20,

21,

22]. The short-term outcomes of RAS are encouraging and not only comparable to those provided by VATS or open surgery, but also superior [

16,

19,

23,

24]. Recently, RAS has been demonstrated to be a feasible alternative to RAL for conserving lung function in patients with respiratory-compromised lung cancer [

25], but achieving favorable oncological outcomes remains the top priority for thoracic surgeons. The NCCN guidelines [

2] emphasized that both VATS and RATS were viable options for patients without anatomical or surgical contraindications, provided that the fundamental oncologic principles and dissection techniques of thoracic surgery are not compromised. Nonetheless, the oncologic efficacy and long-term outcomes of this procedure remain under investigation, primarily due to the limited median follow-up, which, in the literature, currently does not exceed 5 years [

16,

26]. The recently published Phase 3 clinical trial, JCOG0802, demonstrated the benefits of segmentectomy versus lobectomy in terms of overall survival for patients with small peripheral NSCLC, even though the proportion of patients with local relapse was almost double for segmentectomy compared to lobectomy (10.5% vs 5.4%, p = 0.0018) [

4].

Additionally, in the CALGB 140503 trial, published in The Lancet one year later, the authors concluded that sublobar resection was not inferior to lobectomy in terms of disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS) was similar between the two procedures [

5]. To date, both trials confirmed lung segmentectomy as a valid alternative to lobectomy in selected patients with peripheral NSCLC < 2 cm, in terms of oncological outcome, but without any consistent data on the surgical approach (VATS vs RATS vs open approach). Even in our study, RAS offers excellent long-term outcomes for selected patients with early-stage NSCLC, comparable to RAL; the 10-year CSS rate was as high as 92% in the RAS group, underscoring the oncologic efficacy of RAS in achieving durable disease control in selected cases. In particular, in the 5 years of follow-up, our 5-year survival rate seems to be in line with those reported in the literature, even if slightly worse than the 100% 5-year OS found by Zhou and colleagues [

16], who included only stage IA, but better than the 55% 5-year CSS reported by Nguyen and colleagues [

26], who included also patients with pN+ or pT2, as in our study. However, it is essential to note that the rate of LR was significantly higher in the RAS group (12.5%) compared to the RAL group (1.7%) (p = 0.08).

The lower rate of ICU stays observed in the RAS group compared to the RAL group suggests a favorable safety profile, likely attributable to the less extensive nature of segmentectomy compared to lobectomy.

The morbidity rates were comparable between the RAS and RAL groups, indicating that RAS does not increase the risk of postoperative complications compared to RAL. These findings align with the results reported in the literature [

24]. However, the 30-day morbidity rate observed in our cohort appears to be slightly higher than that reported in the literature, which ranges from 10% to 24% [

17]. Nonetheless, the great majority of our postoperative complications were minor, not requiring specific treatment. These findings support the growing adoption of RAS as a viable surgical option for selected patients with early-stage NSCLC, particularly those for whom preservation of lung function is a priority.

One of the key differences observed between RAS and RAL was the extent of lymph node dissection. RAS resulted in significantly lower lymph node retrieval and station sampling, which is consistent with the less extensive nature of segmentectomy. However, this lower nodal retrieval did not result in worse long-term survival or higher relapse rates, suggesting that the oncologic control achieved with RAS is adequate despite the lower extent of lymph node dissection.

The ability of RAS to achieve comparable survival outcomes with less extensive dissection may offer significant benefits in terms of reduced surgical morbidity.

The findings of this study highlight the potential of RAS to combine the benefits of minimally invasive surgery with effective oncologic control, making it an attractive option for selected patients with early-stage disease.

The retrospective nature of this study and its relatively small sample size are notable limitations that must be taken into account when interpreting these results. The lack of randomization poses another limit, as it prevents the establishment of causality. Although propensity score matching was employed to reduce selection bias, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be completely ruled out. Furthermore, the study population consisted primarily of patients with early-stage NSCLC, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to patients with more advanced disease or those with neoplasms other than NSCLC. Finally, the long period considered in the study, influenced by technical and technological developments without taking into account the learning curve, may have introduced an inherited selection bias.

Prospective randomized trials are needed to confirm the long-term outcomes of this study and to explore further the comparative efficacy of RAS and RAL in different patient populations. Additionally, while the study provides valuable insights into the 10-year outcomes of RAS, a longer follow-up is necessary to fully assess the durability of these outcomes.

5. Conclusions

RAS is an effective and safe surgical option for selected patients with ES-NSCLC, offering excellent long-term outcomes with 10-year CSS comparable to RAL. However, lymph node dissection was less extensive in the RAS group, and the incidence of LR was definitely higher compared to RAL. Future research should focus on larger, prospective studies to validate these findings and to explore the potential benefits of RAS in broader cohorts. As robotic surgical technology continues to advance, it is likely to play an increasingly important role in the management of early-stage NSCLC, offering patients less invasive yet effective treatment options.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. (Monica Casiraghi) and R.O.; methodology, M.C. (Monica Casiraghi), A.M.; software, P.M.; validation, L.B. and L.S.; formal analysis, P.M.; investigation, L.G., G.C., C.D. and C.B.; resources, L.B. and G.L.I.; data curation, G.L.I., R.O. and M.C. (Matteo Chiari); writing—original draft preparation, M.C. (Monica Casiraghi) and R.O.; writing—review and editing, M.C. (Monica Casiraghi); visualization, M.C. (Monica Casiraghi); supervision, L.S.; project administration, R.O.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health with Ricerca Corrente and 5x1000 funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, Milan Italy (UID 4367).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

This article was proofread by Carlotta Delmastro (Professional medical translator/editor).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSS: Cancer-Specific Survival |

| RR: rate of relapse |

| ICU: Intensive Care Unit |

| NSCLC: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| RAL: Robotic-Assisted Lobectomy |

| RAS: Robotic-Assisted Segmentectomy |

| CI: confidential interval |

| SD: Standard Deviation |

| LR: local recurrence |

References

- A Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, version 9.2024. 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf.

- Ginsberg, R.J.; Rubinstein, L.V. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995, 60, 615–622; discussion 622–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, H.; Okada, M.; Tsuboi, M.; Nakajima, R.; Suzuki, K.; Aokage, K.; Aoki, T.; Okami, J.; Yoshino, I.; Ito, H.; et al. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral non-small-cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 1607–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altorki, N.; Wang, X.; Kozono, D.; Watt, C.; Landrenau, R.; Wigle, D.; Port, J.; Jones, D.R.; Conti, M.; Ashrafi, A.S.; et al. Lobar or Sublobar Resection for Peripheral Stage IA Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J.; Flores, R.M.; Rusch, V.W. Robotic assistance for video-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy: Technique and initial results. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2006, 131, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, G.; Palleschi, A.; Mendogni, P.; Tosi, D. Approaches and outcomes of Robotic-Assisted Thoracic Surgery (RATS) for lung cancer: A narrative review. J. Robot. Surg. 2022, 17, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Feng, Q.; Huang, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Luo, F. Updated Evaluation of Robotic- and Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lobectomy or Segmentectomy for Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 853530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, Y.; Tsutani, Y.; Mimae, T.; Tasaki, T.; Miyata, Y.; Okada, M. Surgical Outcomes of Complex Versus Simple Segmentectomy for Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 107, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casiraghi, M.; Cara, A.; Mazzella, A.; Girelli, L.; Iacono, G.L.; Uslenghi, C.; Caffarena, G.; Orlandi, R.; Bertolaccini, L.; Maisonneuve, P.; et al. 1000 Robotic-assisted lobectomies for primary lung cancer: 16 years single center experience. Lung Cancer 2024, 195, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovic, J.; Al-Hussaini, A.; Al-Shehab, D.; Threader, J.; Villeneuve, P.J.; Ramsay, T.; Maziak, D.E.; Gilbert, S.; Shamji, F.M.; Sundaresan, R.S.; et al. Evaluating the Reliability and Reproducibility of the Ottawa Thoracic Morbidity and Mortality Classification System. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011, 91, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Ning, J.; Huang, X. Empirical Comparison of the Breslow Estimator and the Kalbfleisch Prentice Estimator for Survival Functions. J Biom Biostat. 2018, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignam, J.J.; Kocherginsky, M.N. Choice and Interpretation of Statistical Tests Used When Competing Risks Are Present. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4027–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylewski, M.R.; Ohaeto, A.C.; Pereira, J.F. Pulmonary Resection Using a Total Endoscopic Robotic Video-Assisted Approach. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 23, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardolesi, A.; Park, B.; Petrella, F.; Borri, A.; Gasparri, R.; Veronesi, G. Robotic Anatomic Segmentectomy of the Lung: Technical Aspects and Initial Results. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 94, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Huang, J.; Pan, F.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Song, W.; Luo, Q. Operative outcomes and long-term survival of robotic-assisted segmentectomy for stage IA lung cancer compared with video-assisted thoracoscopic segmentectomy. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perroni, G.; Veronesi, G. Robotic segmentectomy: Indication and technique. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 3404–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerfolio, R.J.; Watson, C.; Minnich, D.J.; Calloway, S.; Wei, B. One Hundred Planned Robotic Segmentectomies: Early Results, Technical Details, and Preferred Port Placement. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 101, 1089–1095; Discussion 1095–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Hu, J.; Han, Y.; Huang, M.; Xiang, J.; Li, H. Early outcomes of robotic versus thoracoscopic segmentectomy for early-stage lung cancer: A multi-institutional propensity score-matched analysis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 160, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruki, T.; Kubouchi, Y.; Kidokoro, Y.; Matsui, S.; Ohno, T.; Kojima, S.; Nakamura, H. A comparative study of robot-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and conventional approaches for short-term outcomes of anatomical segmentectomy. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023, 72, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.; Akhmerov, A.; Justo, M.; Fong, A.; Mahfoozi, A.; Soukiasian, H.J.; Imai, T.A. Trends in segmentectomy for the treatment of stage 1A non-small cell lung cancers: Does the robot have an impact? Am. J. Surg. 2022, 225, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneuertz, P.J.; Zhao, J.; D’sOuza, D.M.; Abdel-Rasoul, M.; Merritt, R.E. National Trends and Outcomes of Segmentectomy in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 113, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.Z.; Tan, Z.H.; Li, J.B.; Xie, C.L.; Sun, T.Y.; Long, H.; Fu, J.H.; Zhang, L.J.; Lin, P.; Yang, H.X. Comparison of Short-Term Outcomes Between Robot-Assisted and Video-Assisted Segmentectomy for Small Pulmonary Nodules: A Propensity Score-Matching Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023, 30, 2757–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Tang, Z.; Mi, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, K.; Liang, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, L. Robotic and video-assisted lobectomy/segmentectomy for non-small cell lung cancer have similar perioperative outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 3883–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echavarria, M.F.; Cheng, A.M.; Velez-Cubian, F.O.; Ng, E.P.; Moodie, C.C.; Garrett, J.R.; Fontaine, J.P.; Robinson, L.A.; Toloza, E.M. Comparison of pulmonary function tests and perioperative outcomes after robotic-assisted pulmonary lobectomy vs segmentectomy. Am. J. Surg. 2016, 212, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Gharagozloo, F.; Tempesta, B.; Meyer, M.; Gruessner, A. Long-term results of robotic anatomical segmentectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2018, 55, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).