1. Introduction

Rotator cuff (RC) tears and their related symptoms impose a significant burden on the healthcare system, causing 28.8% of individuals to seek consultation with general practitioners for shoulder pain [

1]. RC tears are common contributors to shoulder discomfort and impairment, becoming more prevalent as individuals age [

2]. Despite extensive research, the exact cause of shoulder pain resulting from RC tears remains unclear. Asymptomatic RC tears were found to be twice as prevalent as symptomatic RC tears in the general population [

3]. These findings add to the complexity of understanding shoulder pain associated with RC tears. The relationships between the severity of RC tears, pain, and disability experienced by individuals are complex and vary from person to person. Hence, findings on imaging modalities do not align with patient-reported pain measures.

Recent research has reported that the prevalence of central sensitization in individuals with chronic RC tears is 39.4%, which is higher than that reported in individuals with spine and knee musculoskeletal disorders [

4]. However, the evidence concerning central sensitization in rotator cuff related shoulder pain (RCRSP) remains ambiguous [

5], likely because of the inherent difficulties in accurately and consistently measuring central sensitization directly in humans. Compared with those at rest, individuals with RCRSP often experience increased pain levels when moving their shoulders [

6]. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of measuring movement-evoked pain (MEP) in musculoskeletal disorders [

7]. MEP represents a significant yet commonly ignored obstacle to patient adherence to exercise programs [

8]. The mechanisms underlying pain at rest and MEP are also distinct [

9]. Peripheral and central sensitization processes seem to contribute to the development of MEP [

10,

11]. The term "sensitivity to movement-evoked pain" refers to the heightened experience of pain during a movement in reaction to repeated movements, such as repeatedly raising the arm [

12]. However, research has revealed no correlation between the number of abnormal RC tendons and the occurrence of pain triggered by movement in the shoulder [

13,

14].

Temporal summation (TS) is a psychophysical phenomenon assessed via quantitative sensory testing in which a train of identical, brief noxious pulses (typically mechanical or thermal, delivered at ~0.3–1 Hz) produces progressively greater pain ratings, even though each stimulus has the same intensity. TS reflects the perceptual correlate of wind up, the electrophysiological process in dorsal horn wide dynamic range neurons whereby repeated C fibre input at similar frequencies leads to a progressively increasing discharge of action potentials [

15].

In many chronic pain conditions, including the RCRSP, everyday movements repeatedly activate peripheral nociceptors in a way that mimics the brief, repeated pulses used in TS paradigms. These patients often exhibit exuberant TS (i.e., greater increases in pain ratings across the pulse train) because their spinal circuits are primed. Spinal circuits become “primed” in chronic pain patients through convergence of synaptic plasticity, loss of inhibitory control, neuroimmune activation, and altered descending modulation. These changes lower the threshold for dorsal horn neurons to fire and to summate successive C fibre inputs so that even normal or mildly noxious afferent volleys produce exaggerated pain. As such, these patients may be prone to amplified pain during repetitive arm movements. By identifying individuals with pronounced TS, clinicians can both anticipate which patients will struggle most with activity-related pain and tailor interventions, such as graded exposure, to target the underlying central facilitation. In the RCRSP, however, it remains unclear whether the severity of MEP is significantly related to TS. Therefore, this study aims to establish the relationships among TS, pain at rest, and MEPs in individuals with RC tears.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study was conducted within a prospective longitudinal study that aimed to develop a prediction model for the development of chronic pain in individuals undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR). Data collection was performed preoperatively before the ARCR procedure. This study was conducted between August 2022 and January 2024. Institutional ethics committee (Approval number IEC 40/2020) approval was obtained before the commencement of the study. The trial was registered under the clinical trial registry with a registration number (CTRI/2021/04/032929). All participants received a participant information sheet and signed a written informed consent form before participating in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

2.2. Study Population

The study's inclusion criteria were individuals aged 18 to 70 years, with unilateral symptomatic RC tears diagnosed through clinical examination and/or diagnostic imaging (diagnostic ultrasound/magnetic resonance imaging), and participants with RC tears resulting from degenerative and traumatic causes. The exclusion criteria included a history of shoulder surgery; other shoulder disorders, such as osteoarthritis, instability, labral tear, or infection; a diagnosis of psychological disorders; chronic pain in other body regions; systemic inflammatory conditions; neurological disorders; or malignancy.

2.3. Procedure

Demographic characteristics, including age, sex, height, weight, duration of symptoms, affected side, and dominant side, were recorded for all participants who agreed to participate in the study. The participants were given a standardized briefing to introduce them to the numerical pain rating scale (NRS). A familiarization session with the TS was conducted before the data were collected, which included a trial of the TS with a mechanical stimulus on the contralateral knee at the area of the tibialis anterior muscle. All the data were obtained by a qualified physiotherapist (APB) with 12 years of clinical experience.

2.4. Temporal Summation

The participants were told to use an NRS from 0 to 10, with zero indicating “no pain” and 10 denoting “most intense imaginable pain”. Each participant was subsequently instructed to rate their level of pain at the test location on a 0–10 scale. Mechanical TS was assessed on the dorsal aspect of the unaffected forearm. The mechanical stimuli were delivered via Semmes Weinstein monofilament log 6.65, which was calibrated to bend at 300 g of pressure. The monofilament was used to deliver the stimuli, and it was positioned vertically above the target site of contact. Initially, the researcher applied a single pin-prick stimulus, followed by a series of 10 pin-prick stimuli delivered at a frequency of 1 Hz within a 1 cm² area. Pain ratings were recorded after the first and tenth stimuli. This procedure was repeated three times, and the average TS difference (TS

D) score was used for analysis. The TS

D score was calculated by subtracting the first stimulus's pain intensity rating (TS

1) from the tenth stimulus's intensity rating (TS

10) [

16].

2.5. Movement-Evoked Pain

The participants provided their pain ratings on the NRS for current pain at rest and movement-evoked pain. Pain at rest was assessed while the patient sat upright on the edge of the bed without using any support or sling for the affected shoulder. Measuring pain at rest as current pain intensity while seated immediately before performing a task as baseline pain is suggested, as it allows for direct comparison between pain at rest and MEP [

17]. The participants were instructed to actively lift their affected arm as much as possible in the scaption plane to measure the MEP, and the pain intensity was recorded at the end of the available movement. This trial was repeated three times on the affected shoulder, with a rest period of 2 minutes between each repetition. The average intensity of the three trials was used to calculate movement-evoked pain. Higher values represented greater pain ratings on the NRS. Testing MEPs while the shoulder is in active motion until the onset of pain or at a maximum range of motion has been established as a reliable method for evaluating MEPs in patients with RCRSP [

18].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The Jamovi 2.3.26 software was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were employed to present participant demographic data. As the data did not follow a normal distribution, nonparametric statistics were used according to the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test. The relationships between TS, movement-evoked pain, and pain at rest in RC tear participants were evaluated via Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. The values were expressed as correlation coefficients and were interpreted as described by Hinkle et al. (2003), where ‘0’ means no relationship, ‘0.00 to 0.30’ means little if any correlation, ‘0.30 to 0.50’ means a low positive correlation, ‘0.50 to 0.70’ means a moderate positive correlation, ‘0.70 to 0.90’ means a high positive correlation, and ‘0.90 to 1.00’ means a very high positive correlation [

19]. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the associations between TS, movement-evoked pain, and pain at rest in participants subgrouped into acute pain (< 3 months) and chronic pain (> 3 months). The level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

This cross-sectional study examined 85 participants, and

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the participants. Most of the participants were middle-aged males who were right-hand dominant, and nearly half of them experienced pain on the dominant side. The duration of symptoms varied widely, and participants with both acute (n=40) and chronic (n=45) pain were included. The average pain score indicates greater pain intensity during movement than at rest. The mean scores of TS at the end of the first and tenth stimuli are displayed alongside the mean difference score for TS (TS

D=TS

10 -TS

1).

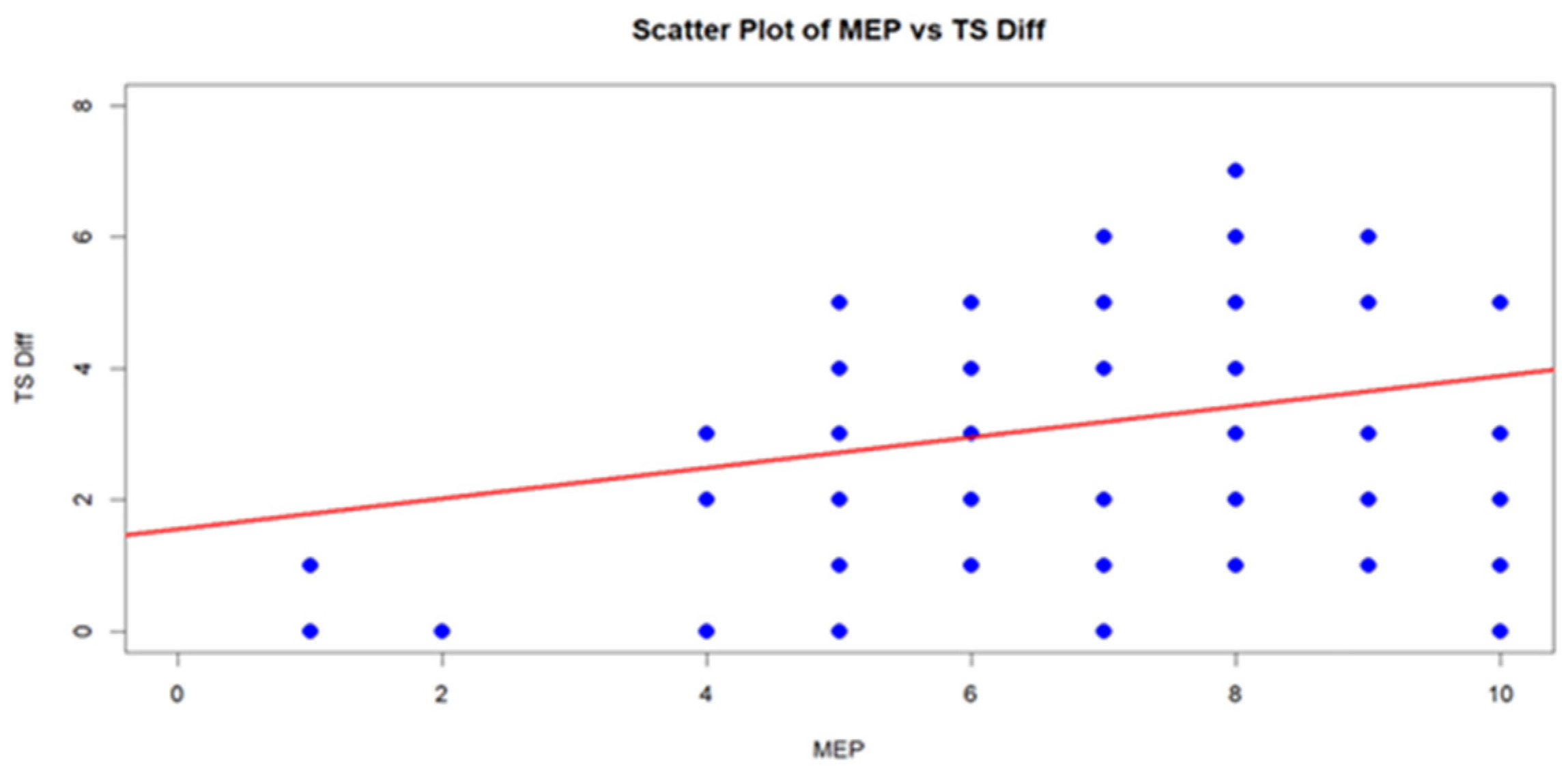

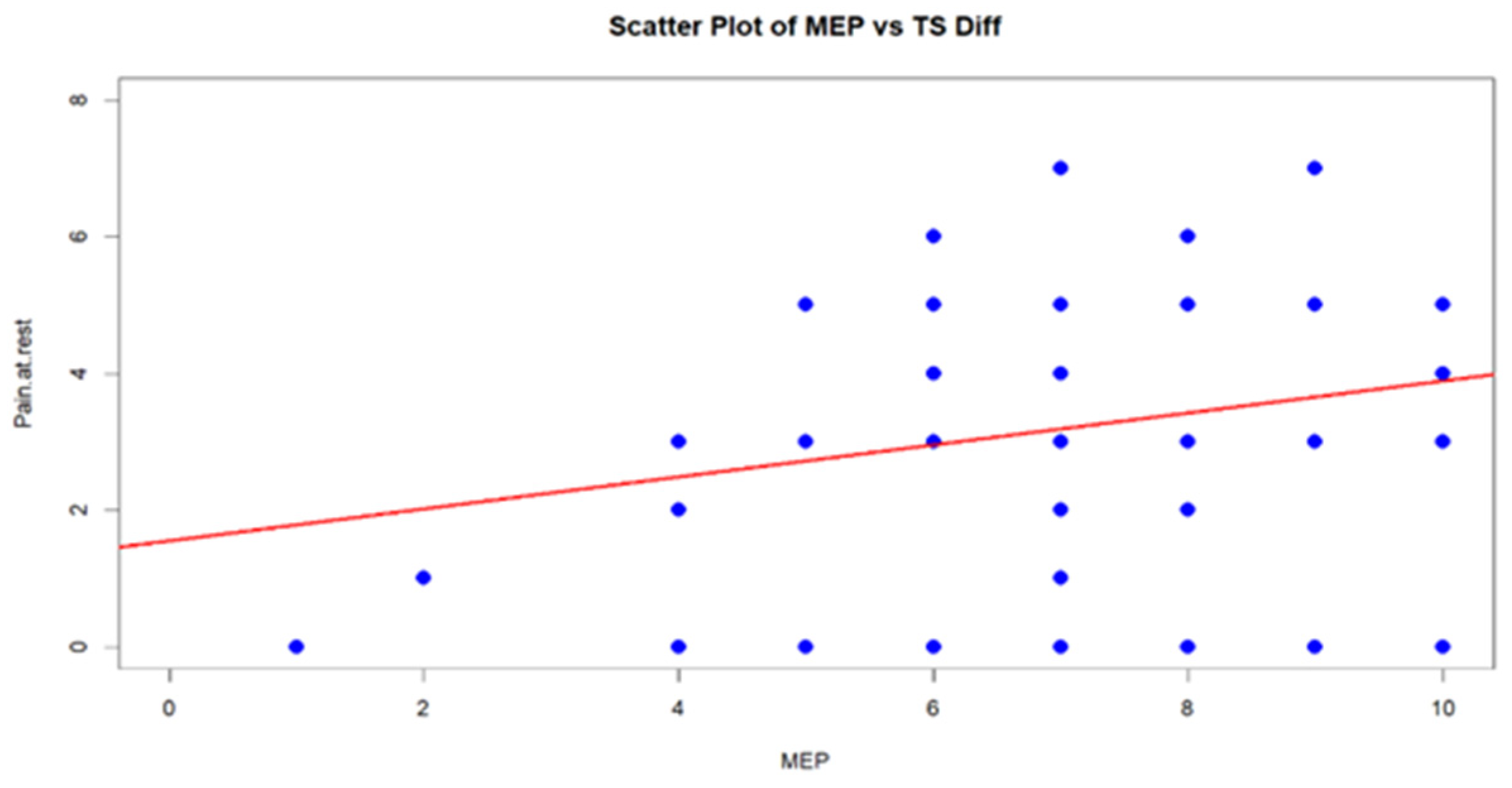

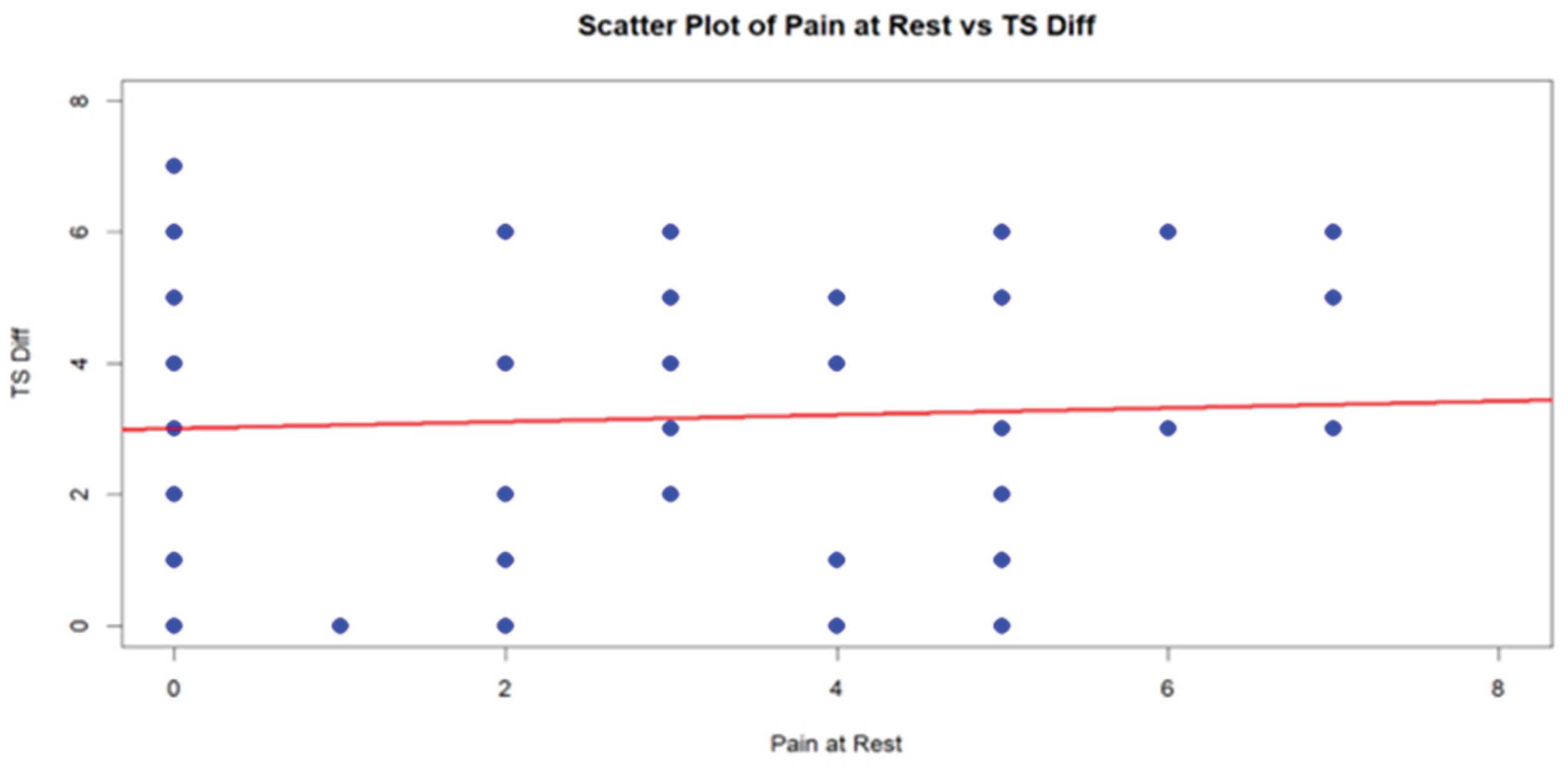

Table 2 displays the correlations between TS, pain at rest, and MEP in participants with RC tears. A weak, statistically significant correlation was found between the mechanical TS and MEP (r = 0.23; p = 0.02). MEP and pain at rest also demonstrated a weak, statistically significant correlation (r = 0.30; p = 0.005), whereas TS and pain at rest were not correlated (r = 0.04; p = 0.68).

As shown in

Table 3, the logistic regression analysis revealed various associations between different pain durations and factors. A relatively high odds ratio was observed for pain at rest (1.018 with CI (0.82 - 1.264)) and TS (1.153 with CI (0.901-1.475)), suggesting a potential association between pain at rest, TS, and the presence of acute or chronic pain. In contrast, MEP had a lower odds ratio (0.773 with CI (0.599--0.998)), indicating an inverse relationship with acute and chronic pain.

Despite these associations, the analysis also revealed that, within the subgroup of participants with acute and chronic pain, there was no significant association between TS and pain at rest. The model demonstrated mild predictive power, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.600 and a nonsignificant p value (0.189), suggesting limited predictive ability. Furthermore, the model exhibited a low McFadden’s R2 value (R2McF = 0.04), indicating that it explained only a small proportion of the variance in pain outcomes.

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 display scatter plots of the correlations between MEP and TS, between MEP and pain at rest, and between TS and pain at rest, respectively.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the correlations among TS, pain at rest, and MEPs in individuals with symptomatic RC tears. A weak but statistically significant correlation was found between TS and MEP and between pain at rest and MEP, but there was no correlation between TS and pain at rest.

According to a recent study comparing quantitative sensory testing measurements with MEPs in persistent low back pain patients, TS explained 12% of the variation in MEPs [

20]. In whiplash injuries, TS could account for 20% of the variance in sensitivity to movement-evoked pain, suggesting that certain processes underlying MEP also intersect with TS processes [

12]. In individuals with knee osteoarthritis, the association between sensitivity to physical activity and TS on the index knee was relatively modest [

21]. The pain-movement conceptual model emphasizes the interdependence between pain and movement [

22]. A recent study revealed that an imbalance in pain modulation, characterized by increased pain facilitation detected through TS, could significantly contribute to the severity of movement-related pain and impaired physical function in individuals with chronic low back pain [

23]. A significant association was found between the TS of mechanical pain and the severity of clinical pain in adults suffering from chronic low back pain [

24]. Our findings enhance the understanding of MEP in individuals with symptomatic RC tears. A deeper understanding of how facilitatory pain pathways influence MEP can lead to improvements in clinical practice and research. Even though the intensity of the mechanical stimuli remained constant throughout the TS procedure, RC tear patients reported noticeably more pain in response to the last application of the stimulus than the first. The weak linear correlation between the TS and MEP in our study points towards two distinct mechanisms for pain during movement and the facilitating process of ascending pain.

It has been suggested that changes in the central nervous system, lowering nociceptive thresholds, and peripheral mechanical factors, such as the activation of silent nociceptors, are responsible for MEP [

11,

25]. Unlike self-reported validated questionnaires, the MEP provides a pain rating immediately after completing a physical activity. The observed weak, statistically significant correlation between MEP and pain at rest suggests that these two pain experiences, although related, are distinct and likely influenced by different underlying mechanisms. A study examining the association between pain at rest and MEP in knee osteoarthritis patients concluded that there was an absence of correlation between these two pain phenomena [

17]. Pain at rest is frequently associated with ongoing inflammation or tissue damage, which leads to persistent nociceptor activation even in the absence of movement. In contrast, MEP involves the activation of previously silent nociceptors that specifically respond to mechanical stimuli during movement [

25]. This activation can occur even without overt inflammation, indicating a distinct peripheral sensitization process. Furthermore, MEP has been linked to central sensitization, where heightened sensitivity can amplify pain perception during movement, also affecting pain at rest. In summary, the weak correlation between MEP and pain at rest reflects their distinct underlying peripheral pathophysiological mechanisms. Recognizing and assessing both types of pain can inform more comprehensive pain management strategies.

The present findings suggest differential associations between pain characteristics and acute and chronic pain states. Pain at rest and TS were positively associated with the presence of acute or chronic pain, although these associations did not reach statistical significance. These findings are partially consistent with those of previous studies, indicating that central sensitization mechanisms, of which TS is a hallmark, are often elevated in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain [

26]. MEP, in contrast, showed a statistically significant inverse association, which may reflect the protective behavior observed in chronic pain states where individuals avoid movement to reduce perceived threat or discomfort [

27].

Study Limitations

This study is not without limitations. Since all our participants were diagnosed with symptomatic RC tears and were on pain medications, we did not consider the role of pain medications in facilitating pain mechanisms and MEP. Peripheral processes, such as muscle weakness, can impact arm elevation while MEP is measured; the range of shoulder elevation was not considered in our study. The initial study question aimed to develop a prediction model for chronic pain following ARCR that formed the basis for sample size estimation in this secondary analysis. The sample size calculation was not conducted with the objective of this study, but future investigations should include a more rigorous uptake of study findings. The duration of pain among our participants varied from acute to chronic, which may significantly influence the correlation results, as TS is a phenomenon commonly associated with chronic pain.

Implications

From a clinical standpoint, a deeper comprehension of the interplay between various measures of pain integration may hold significant value in assessing the risk of adverse pain-related outcomes. Our findings indicate that individuals with sensitized responses to mechanical tasks may experience pain during everyday activities such as arm elevation.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated a weak but significant correlation between MEP and TS in individuals with symptomatic RC tears, suggesting partially overlapping yet distinct underlying pain mechanisms. No association was observed between pain at rest and TS, supporting the hypothesis that different neurophysiological pathways may drive resting and MEP. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating both MEP and TS in clinical assessments, as they may inform targeted interventions for movement-related shoulder pain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.B. and G.A.M.; methodology, A.P.B.; software, V.J.; formal analysis, V.J.; investigation, V.P. and K.K.V.A.; A.P.B.; writing—review and editing, J.M.E. and M.M; supervision, G.A.M., V.P., K.K.V.A., J.M.E., M.M., project administration, G.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Kasturba Hospital, Manipal) of MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION with the approval number IEC: 40/2020 on 15th January 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the

corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the participants for their time and cooperation in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MEP |

Movement-Evoked Pain |

| RC |

Rotator Cuff |

| TS |

Temporal Summation |

| RCRSP |

Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain |

| ARCR |

Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair |

| NRS |

Numerical Pain Rating Scale |

References

- Hinsley, H.; Ganderton, C.; Arden, N.K.; Carr, A.J. Prevalence of rotator cuff tendon tears and symptoms in a Chingford general population cohort, and the resultant impact on UK health services: a cross-sectional observational study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, M.; Di Carlo, L.; Salini, V.; Schiavone, C. Risk factors associated to bilateral rotator cuff tears. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2017, 103, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minagawa, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Abe, H.; Fukuda, M.; Seki, N.; Kikuchi, K.; Kijima, H.; Itoi, E. Prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears in the general population: From mass-screening in one village. J. Orthop. 2013, 10, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, R.; Yang, R.; Ning, N. Central sensitization syndrome in patients with rotator cuff tear: prevalence and associated factors. Postgrad. Med. 2023, 135, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haik, M.N.; Evans, K.; Smith, A.; Henríquez, L.; Bisset, L. People with musculoskeletal shoulder pain demonstrate no signs of altered pain processing. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pr. 2019, 39, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, D.C.; Tangrood, Z.J.; Wilson, R.; Sole, G.; Abbott, J.H. Tailored exercise and manual therapy versus standardised exercise for patients with shoulder subacromial pain: a feasibility randomised controlled trial (the Otago MASTER trial). BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemans, L.; Polli, A.; Nijs, J.; Wideman, T.; Bandt, H.D.; Beckwée, D. It Hurts to Move! Intervention Effects and Assessment Methods for Movement-Evoked Pain in Patients With Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2022, 52, 345–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobkin, P.L.; Da Costa, D.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Dritsa, M.; Du Berger, R.; Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Lowensteyn, I. Adherence during an individualized home based 12-week exercise program in women with fibromyalgia. J. Rheumatol. 2006, 33, 333–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, L.V.; Abner, T.S.S.; Sluka, K.A. Does exercise increase or decrease pain? Central mechanisms underlying these two phenomena. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 4141–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, K.A.; Chimenti, R.L.; Alsouhibani, A.M.; Berardi, G.; Booker, S.Q.; Knox, P.J.; Post, A.A.; Merriwether, E.N.; Wilson, A.T.; Simon, C.B. Through the Lens of Movement-Evoked Pain: A Theoretical Framework of the “Pain-Movement Interface” to Guide Research and Clinical Care for Musculoskeletal Pain Conditions. J. Pain 2024, 25, 104486–104486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullwood D, Means S, Merriwether EN, Chimenti RL, Ahluwalia S, Booker SQ. Toward understanding movement-evoked pain (MEP) and its measurement: A scoping review. Clin J Pain. 2021;37:61–8.

- Wan, A.K.; Rainville, P.; O'LEary, S.; Elphinston, R.A.; Sterling, M.; Larivière, C.; Sullivan, M.J. Validation of an index of Sensitivity to Movement-Evoked Pain in patients with whiplash injuries. PAIN Rep. 2018, 3, e661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaiti, R.K.; Caneiro, J.; Gasparin, J.T.; Chaves, T.C.; Malavolta, E.A.; Gracitelli, M.E.; Meulders, A.; da Costa, M.F. Shoulder pain across more movements is not related to more rotator cuff tendon findings in people with chronic shoulder pain diagnosed with subacromial pain syndrome. PAIN Rep. 2021, 6, e980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Sanders R, An Q, Baumgarten KM, Bishop JY, et al. Symptoms of pain do not correlate with rotator cuff tear severity: A cross-sectional study of 393 patients with a symptomatic atraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tear. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:793–800.

- Staud, R.; Vierck, C.J.; Cannon, R.L.; Mauderli, A.P.; Price, D.D. Abnormal sensitization and temporal summation of second pain (wind-up) in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. PAIN® 2001, 91, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.-T.; You, D.S.; Law, C.S.W.; Darnall, B.D.; Gross, J.J.; Manber, R.; Mackey, S. Association between temporal summation and conditioned pain modulation in chronic low back pain: baseline results from 2 clinical trials. PAIN Rep. 2021, 6, e975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano-Meca, J.A.; Gacto-Sánchez, M.; Montilla-Herrador, J. Movement-evoked pain is not associated with pain at rest or physical function in knee osteoarthritis. Eur. J. Pain 2024, 28, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Mani, R.; Zeng, J.; Chapple, C.M.; Ribeiro, D.C. Test-retest reliability of movement-evoked pain and sensitivity to movement-evoked pain in patients with rotator cuff-related shoulder pain. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2023, 27, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle DE, Wiersma W, Jurs SG. Applied statistics for the behavioral sciences. Boston: Houghton Mifflin College Division; 2003.

- Simon CB, Lentz TA, Ellis L, Bishop MD, Fillingim RB, Riley JL III, et al. Static and dynamic pain sensitivity in adults with persistent low back pain: Comparison to healthy controls and associations with movement-evoked pain versus traditional clinical pain measures. Clin J Pain. 2021;37:494–503.

- Wideman, T.H.; Finan, P.H.; Edwards, R.R.; Quartana, P.J.; Buenaver, L.F.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Smith, M.T. Increased sensitivity to physical activity among individuals with knee osteoarthritis: Relation to pain outcomes, psychological factors, and responses to quantitative sensory testing. PAIN® 2014, 155, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, K.A.; Fox, E.J.; George, S.Z. Toward a Transformed Understanding: From Pain and Movement to Pain With Movement. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 1503–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstreet, D.S.; Michl, A.N.; Penn, T.M.; Rumble, D.D.; Aroke, E.N.; Sims, A.M.; King, A.L.; Hasan, F.N.; Quinn, T.L.; Long, D.L.; et al. Temporal summation of mechanical pain prospectively predicts movement-evoked pain severity in adults with chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, M.A.; Bulls, H.W.; Trost, Z.; Terry, S.C.; Gossett, E.W.; Wesson-Sides, K.M.; Goodin, B.R. An Examination of Pain Catastrophizing and Endogenous Pain Modulatory Processes in Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain. Pain Med. 2015, 17, 1452–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, D.B.; Simon, C.B.; Manini, T.M.; George, S.Z.; Riley, J.L.; Fillingim, R.B. Movement-evoked pain: transforming the way we understand and measure pain. PAIN® 2018, 160, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. PAIN® 2011, 152, S2–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J.L.; Thorn, B.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Keefe, F.; Martin, M.; Bradley, L.A.; Lefebvre, J.C. Theoretical Perspectives on the Relation Between Catastrophizing and Pain. Clin. J. Pain 2001, 17, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).