1. Introduction

The construction sector is one of the largest contributors to global environmental impacts. It accounts for approximately 36% of final energy use and 39% of energy- and process-related CO₂ emissions globally, while construction and demolition waste (CDW) represent over 30% of the total waste generated in the European Union [

1,

2]. These figures underscore the urgency of transitioning to more sustainable practices and efficient resource management in the built environment.

In response to these challenges, several EU-wide policy frameworks have been introduced, including the European Green Deal, the Circular Economy Action Plan, the Renovation Wave strategy, and the Level(s) framework for sustainable buildings. These initiatives promote life cycle thinking, carbon neutrality, and the reuse of materials in construction [

3,

4,

5,

6]. To support these goals, the construction sector is increasingly exploring the use of enabling methodologies and tools such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Agile Project Management (APM). BIM provides data-rich digital models across the life cycle of buildings, supporting circular design and real-time decision-making [

7,

8]. APM promotes flexibility, stakeholder involvement, and iterative workflows [

9].

Despite this potential, the integrated application of CE, BIM, and APM remains limited, particularly among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which account for over 99% of construction firms in the EU [

10,

11]. SMEs typically face constraints in terms of financial and human capital, which impedes the adoption of digital technologies and circular approaches [

12]. Research shows that SMEs lag in BIM proficiency and strategic readiness for circular transformation [

13].

BIM plays a critical role in enabling circularity in the built environment by providing a unified platform for material tracking, life-cycle assessment (LCA), and scenario modelling for reuse and disassembly [

7,

8]. As a digital backbone, BIM facilitates early-stage decisions that influence the entire building life cycle, including the reuse of components at end-of-life and reductions in embodied carbon.

Meanwhile, the application of agile methods in construction is still emerging. Agile project management, widely used in IT, emphasizes responsiveness and adaptability—qualities increasingly needed in sustainable construction [

14,

15]. Initial case studies show that agile approaches can enhance coordination, reduce delays, and support iterative design, particularly in modular construction or prefabricated systems [

9,

16]. However, the cultural shift required to implement agile in the AEC sector remains a significant challenge.

The integration of circular economy principles, BIM, and agile management is an emerging research frontier. Recent conceptual and practice-led studies have proposed frameworks and platforms that combine these elements into coherent methodologies, enabling construction firms—especially SMEs—to enhance resource efficiency and regenerative capacity [

13,

16].

This paper contributes to this discourse by presenting an integrated framework for CE–APM-BIM synergy, supported by insights from the BLOOM project dataset and a cross-national SME survey. The goal is to inform both policy and practice by outlining actionable pathways for implementing circularity through digital and agile tools in the construction sector.

The paper addresses the gap between successful CE implementation and potential by developing a conceptual framework that integrates CE, APM, and BIM in the construction sector, with a particular focus on SMEs in Mediterranean and Central European regions. Drawing from secondary data (BLOOM project) and a targeted readiness survey, the study aims to assess current practices, identify implementation barriers, and outline actionable pathways for integration. Accordingly, the following research questions guide this work:

How can circular economy principles, agile project management practices, and BIM methodologies be jointly applied to improve resource efficiency and flexibility in construction projects?

What synergies, trade-offs, and barriers arise when integrating these approaches into SME-led projects, and how are they manifested in current practice (with reference to EU/Mediterranean contexts)?

How can the insights from literature and practice be synthesized into a conceptual framework to guide SMEs in implementing circular and agile BIM-driven construction processes?

By addressing these questions, the study contributes to both academic discourse and industry practice, offering an integrative perspective that aligns digitalization, agility, and circularity in support of a regenerative built environment.

Unlike previous studies that have examined Circular Economy (CE), Agile Project Management (APM), or Building Information Modeling (BIM) in isolation or partial combinations, this paper presents the first empirically grounded integration of all three into a coherent framework tailored to the needs of construction SMEs. By triangulating findings from two complementary surveys—BLOOM and the CE-APM-BIM 2025 Survey—it develops a novel CE–APM–BIM model that connects strategic orientation, procedural flexibility, and digital enablement. The framework contributes both theoretical insight and actionable guidance for accelerating regenerative construction through integrated, context-sensitive innovation.

2. State of the Practice

Despite growing interest in circularity, agile project management and digitalisation in the AEC sector, only a limited number of real-world cases document the integrated application of Circular Economy (CE), Agile Project Management (APM), and Building Information Modelling (BIM)—especially among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). However, a range of studies offer partial insights into the implementation of these concepts, confirming their individual or paired benefits while identifying critical entry points for full integration.

A notable example describe the case of Links FF&E, a UK-based SME operating in design, production, and fit-out [

17]. The company partially implemented BIM within a 30-month lean transformation programme focused on Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA). This case demonstrated that BIM can effectively streamline processes and operations in SMEs and that technology adoption challenges can be mitigated by focusing on waste reduction and value creation.

Although few studies document cases of SMEs directly implementing CE–APM–BIM in combination, several provide valuable insights into individual components. One SME involved in the BLOOM survey, operating in southern Europe, reported initial attempts to link agile project workflows with resource reuse planning and digital monitoring via BIM tools. The integration of BIM and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) in line with the Swiss sustainability standard Minergie-ECO has been previously explored [

18,

19]. Both studies deliver proof-of-concept evidence that BIM–LCA coupling can transform linear sustainability workflows into circular ones, supporting decision-making with structured and visual information while reducing implementation efforts.

The researchers stress the importance of circularity metrics and computational tools during early design phases [

20]. Their study introduces RhinoCircular, a tool providing real-time feedback on material choices and circularity indicators, such as material passports, enhancing early-stage sustainability assessments.

Further, a demolition planning framework is proposed, that uses BIM to identify recyclable materials, facilitating low-threshold CE practices for construction firms [

21]. This framework supports digital deconstruction planning by linking design data to material recovery strategies—an approach particularly relevant for SMEs operating under tight resource constraints. The broader potential of BIM in enabling circular practices in the built environment is also explored by researchers [

22]. They highlight BIM’s capacity to support circular analysis, manage buildings as material banks, enable new workflows, and integrate supply chains. Similarly, a validated BIM-based circularity assessment tool is developed in a Dutch renovation project [

23], which is significant contribution toward practical circularity across project phases. Their findings confirm that such tools can be effectively adopted in practice and serve as a basis for lifecycle-based circular design strategies. Although the study does not focus specifically on SMEs, the tool was validated through user feedback and successfully applied in a real-world renovation project in the Netherlands. This demonstrates the practical viability of BIM-based circularity metrics and their potential scalability to SME contexts.

In terms of environmental performance evaluation and APM, there is existing application of three different LCA methods to assess a modular Sprint unit [

24]. The study incorporates circularity aspects and allocation rules into its life cycle modelling, offering methodological lessons for circular building design assessment—especially in prefabricated or modular construction. Great case of a U.S.-based SME with a circular business model is presented in the construction sector [

25]. Although not explicitly focused on APM or BIM, their theoretical framework for value creation in circular business models is confirmed through empirical SME data and highlights the influence of contextual factors.

Another relevant SME case, describing the use of agile practices in the implementation of an ERP system within a Canadian construction-related SME, is already published [

26]. Their findings show that agile thinking positively influenced requirement definition and organisational improvement—providing transferrable lessons for CE–APM–BIM transition strategies.

Finally, the theoretical synergy between agile management and circular economy thinking in construction is also researched [

27]. The study identifies mutual reinforcement between agile and circular transitions and recommends agile workflows as a strategic pathway to enhance sustainability and project efficiency.

While none of the reviewed studies report full CE–APM–BIM implementation, partial combinations such as BIM–LCA [

18], BIM with agile ERP [

26], or agile–circular synergies [

26] confirm the practical and conceptual basis for such integration. This reinforces the novelty of the present empirical framework.

Table 1 summarizes the reviewed studies, highlighting the types of integration explored and the extent of SME involvement.

3. Research Design and Methodology

This section outlines the research strategy adopted to investigate the integration of circular economy (CE), Building Information Modeling (BIM), and Agile Project Management (APM) in the construction sector. The study employs a mixed-methods approach combining secondary data analysis and a primary survey, with a particular focus on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) operating in Mediterranean and Central European contexts.

3.1. Research Strategy and Data Sources

The secondary data analysis draws on insights from the BLOOM project, supported by the Norwegian Financial Mechanism 2014–2021, under the Programme Business Development and Innovation Croatia (EEA Grants mechanism). BLOOM explored upskilling needs in the construction sector to support circular construction, as well as green and digital transitions of the construction sector. The dataset comprises both quantitative results and qualitative insights from 153 SME respondents across beneficiary countries, offering robust baseline evidence on sectoral readiness for CE and digital transformation. To update and complement the BLOOM findings, an online CE-APM-BIM survey was conducted between March and May 2025 with 98 SME respondents from five Mediterranean countries (Croatia, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Cyprus). Participants were recruited from a professional mailing list of construction sector experts and practitioners. At the time of the survey, the database contained 5,304 verified email addresses, primarily associated with SMEs and freelance professionals in Mediterranean countries. The survey invitation was distributed via email, followed by two reminder messages and partial telephone follow-up. A total of 98 valid responses were collected over a six-week period.

The sampling strategy combined purposive and convenience sampling, targeting individuals likely to have familiarity or involvement with CE, BIM, or APM practices in construction. While not statistically representative, the sample reflects a cross-section of innovation-active firms and professionals in the region.

3.2. Survey Design and Execution

The BLOOM survey contained 18 structured questions organized into three thematic modules:

Awareness and implementation of circular economy principles

Capacity for digital tools and BIM

Organizational agility and project management practices

Question types included four-point Likert-scale items (to gauge knowledge, implementation levels, and perceived barriers), multiple-choice items, and open-ended qualitative prompts. The instrument was pre-tested with five domain experts and adjusted accordingly to improve clarity and reliability.

Participants were informed about the anonymous and voluntary nature of their participation, in line with ethical research guidelines. No personally identifiable data were collected.

In the BLOOM survey, the sample of 153 respondents primarily comprised SME owners (34%), technical managers (28%), site engineers (18%), and sustainability officers or coordinators (11%), with the remainder split between architects and external consultants. The majority of participants were based in Croatia and Romania, followed by Portugal and Bulgaria. Most respondents represented micro and small enterprises (78%), reflecting the dominant structure of the construction sector in the region. Gender representation skewed male (76%), and the average years of experience among respondents was 14.3 years.

Similarly, the CE–APM–BIM survey included 98 respondents, most of whom were professionals currently active in SME contexts: 31% were project managers, 26% were architects or designers, 19% held BIM-related roles (e.g., coordinators, modellers), and 13% were executives or owners. Notably, 11% identified themselves as working in academic or advisory roles with strong ties to industry. The geographic distribution spanned five Mediterranean countries, with the highest participation from Croatia and Italy. Gender balance remained skewed (72% male), and nearly 60% of participants reported prior involvement in at least one innovation-focused project related to sustainability or digitalization. These characteristics reinforce the credibility and contextual relevance of the dataset for developing the CE–APM–BIM framework.

3.3. Analytical Approach and Ethical Considerations

Quantitative responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics (means, frequencies) and basic cross-tabulations. Responses to open-ended questions underwent inductive thematic analysis using manual coding techniques to identify recurring patterns of motivation, barriers, and integration logic. This analysis was triangulated with findings from the BLOOM dataset to increase validity.

No formal ethics approval was required as the research did not involve sensitive personal data or interventions. Informed consent was implied through voluntary completion of the questionnaire. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT-4, OpenAI, 2024) was used strictly for language editing and formatting support. All analytical and interpretative work was conducted manually by the authors. Data used in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. All data were stored securely and used exclusively for academic purposes in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679.

Additionally, to ensure analytical robustness and increase interpretative validity, survey results were triangulated not only across datasets (BLOOM and CE–APM–BIM), but also across respondent profiles, firm sizes, and countries. While the sample is non-probabilistic, the combination of purposive and convenience sampling enabled a diverse set of perspectives particularly suited for exploratory and framework-generating research. Given the novelty of integrating CE, BIM, and APM in SME contexts, the study follows pragmatist epistemology, prioritizing practical insight and actionable knowledge over statistical generalizability.

The framework developed from this research is thus intended not as a one-size-fits-all solution, but as a contextualized heuristic grounded in empirical observation and theoretical synthesis. It offers a structured starting point for future empirical validation and policy experimentation in the Mediterranean and broader European construction ecosystem.

4. Results

4.1. BLOOM Analysis

The BLOOM dataset, comprising 153 responses from SMEs in the construction sector, provides insight into current levels of awareness, implementation, and perceived obstacles regarding CE, BIM, and agile practices. Over 75% of respondents indicated a high awareness of Circular Economy (CE) principles, particularly regarding material efficiency, waste reduction, and energy use. However, while 63% reported using BIM tools to some extent, the reported use of agile methodologies was significantly lower, with fewer than 20% indicating any practical implementation. Despite awareness, practical integration remains limited. Only 19% of SMEs reported active efforts to combine CE, BIM, and agility in ongoing projects. This indicates a substantial gap between conceptual understanding and implementation capacity.

The most frequently cited barriers to integration included: (1) Lack of training and expertise (78%), (2) Regulatory uncertainty, particularly around secondary materials (52%), (3) Limited access to financing for innovation (46%). Conversely, respondents identified peer learning, pilot funding, and digital toolkits as critical enablers.

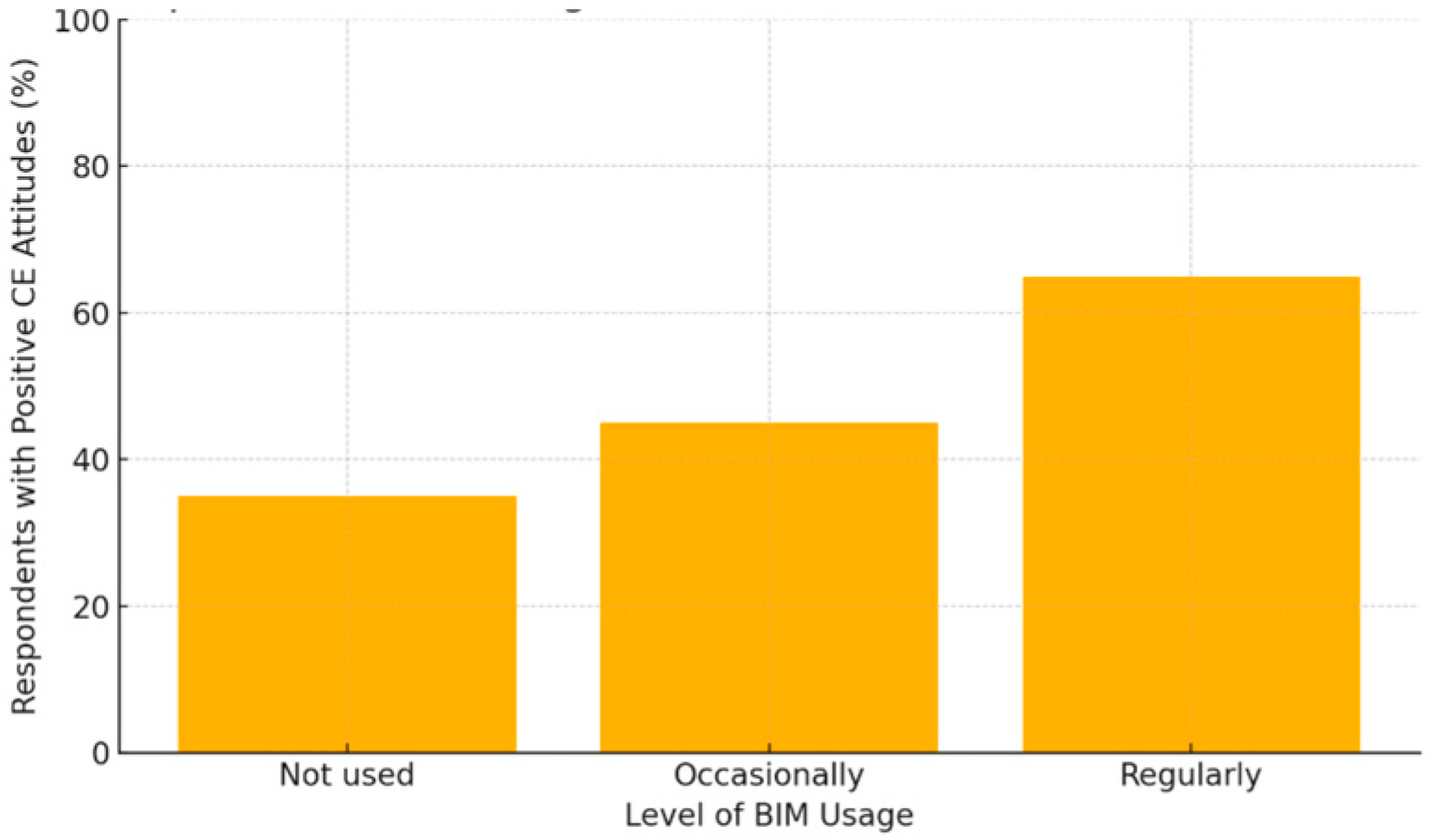

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of respondents expressing positive attitudes toward Circular Economy (CE) principles, segmented by their reported level of Building Information Modeling (BIM) usage. A clear positive trend is observed: among firms not using BIM, only 35% report supportive views of CE, compared to 65% of firms regularly using BIM. These findings suggest a potential correlation between digital maturity and sustainability orientation within the sector, implying that increased BIM adoption may serve as a facilitator for CE-aligned strategies.

The observed correlation between BIM usage and positive attitudes toward CE suggests that digital maturity may serve as a key enabler for broader sustainability integration. To explore this relationship further, the following figure (

Figure 2) examines the extent to which BIM adoption correlates with overall organizational readiness to integrate CE–APM–BIM approaches. This transition from attitudinal support to practical implementation highlights the central role of BIM as a foundational capability for system-wide transformation.

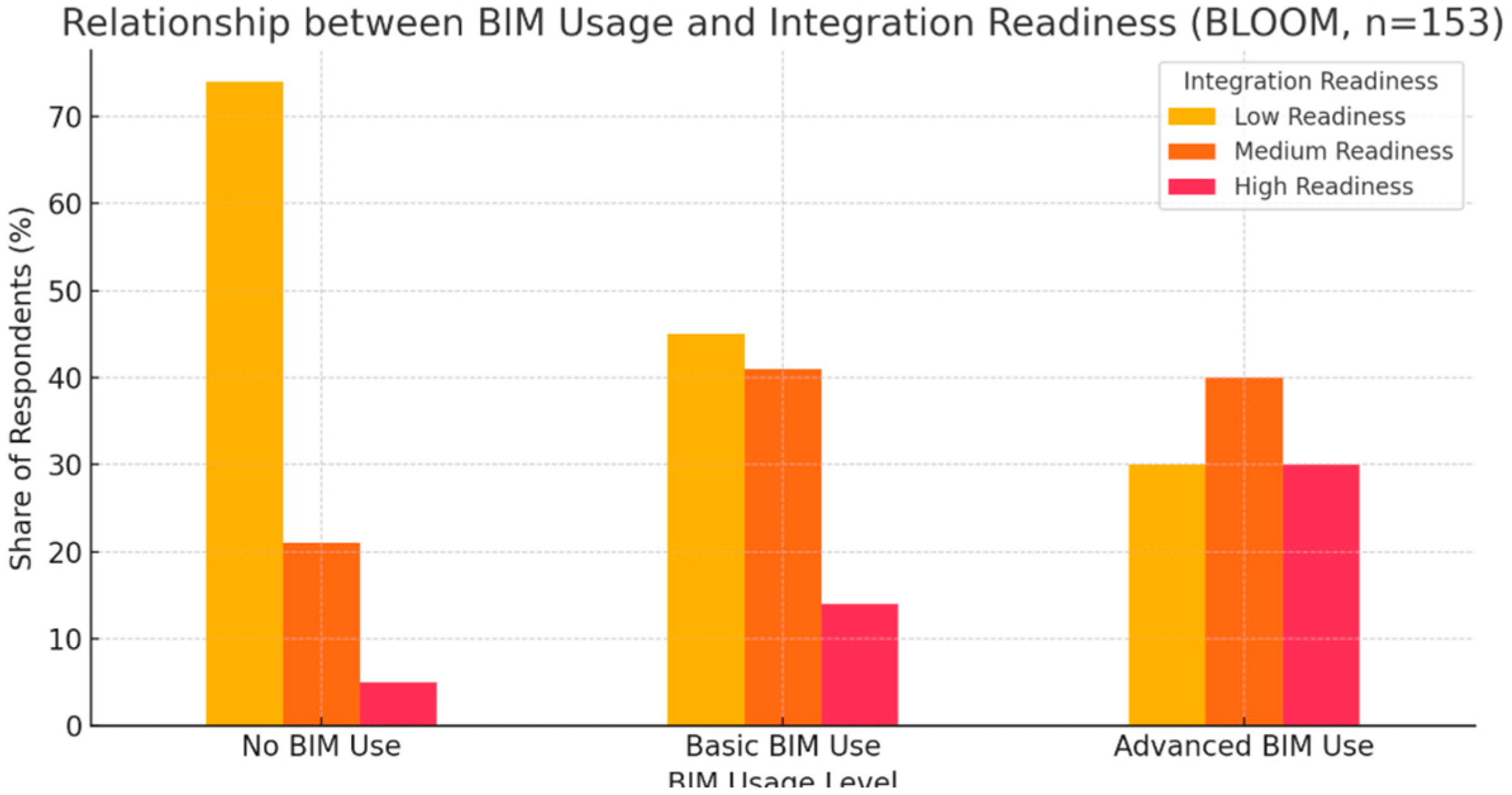

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of integration readiness across three tiers of BIM usage. Among firms not using BIM, only 5% report high readiness to integrate CE–APM–BIM principles, compared to 30% among firms with advanced BIM application. The trend suggests that BIM maturity is strongly associated with higher organizational readiness to engage in holistic, sustainable innovation. Notably, the proportion of low readiness drops significantly as BIM adoption increases. This reinforces the view that digital capabilities serve as a foundation for broader transformation in construction SMEs.

Although the statistical significance of the findings is limited due to the small size of subgroups (e.g., medium CE activity group, n = 8; high CE activity group, n = 12), the data indicate that firms with low engagement in circular economy (CE) practices report no involvement in experimental sustainability projects. Among those with medium CE activity (n = 8), 12.5% reported participation in such initiatives. Notably, no firms in the high CE category (n = 12) reported experimental engagement, which may be attributed to the small sample size and potential underreporting. While these trends should be interpreted with caution, they point to a possible association between increasing CE maturity and innovation-oriented behavior among SMEs in the construction sector.

4.2. CE-APM-BIM Survey Findings

In spring 2025, a rapid survey was conducted to assess the current readiness of construction sector professionals to integrate circular economy (CE) principles, Building Information Modeling (BIM), and agile project management methodologies (APM). The survey, disseminated across five Mediterranean countries, yielded 98 valid responses. Although limited in sample size, the data offer timely insights into emerging patterns of awareness, adoption, and perceived barriers in practice.

Despite widespread conceptual alignment with the goals of sustainability and digital transformation, actual implementation remains limited. A significant majority of respondents (86%) expressed agreement with the strategic importance of integrating CE, APM and BIM, to improve resource efficiency and project adaptability. However, only a small fraction had translated this recognition into operational practice. BIM use was found to be predominantly confined to the design phase, with just 21% of participants reporting application in later project stages such as construction or operation. Agile methodologies, meanwhile, remained largely experimental, with only 12% indicating any form of agile adoption within their current delivery models.

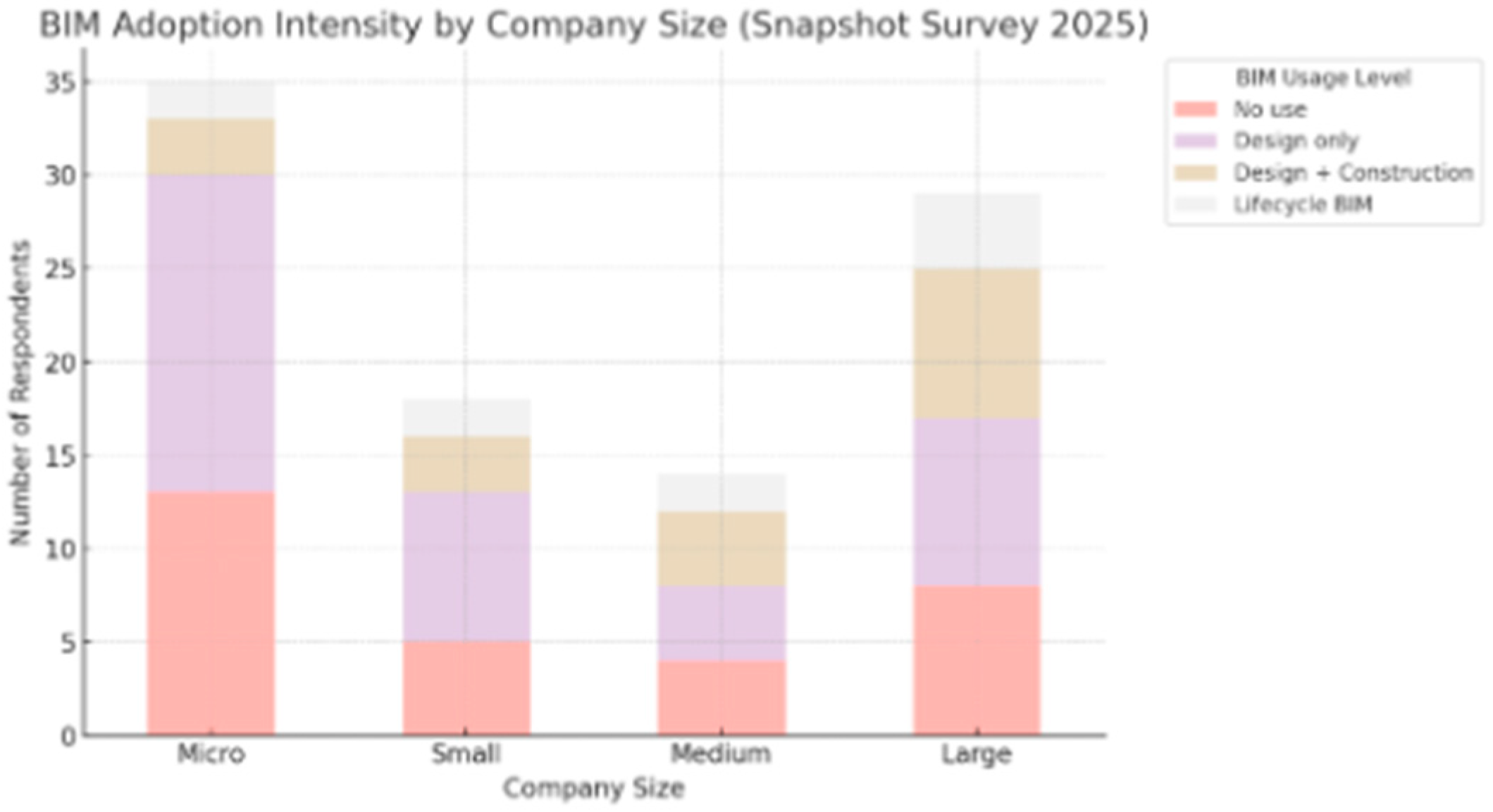

Figure 3 presents the distribution of Building Information Modeling (BIM) usage intensity across firms of varying sizes, as reported in the CE-APM-BIM Survey 2025 (n = 98). BIM usage is categorized across four levels: “No use,” “Design only,” “Design + Construction,” and “Lifecycle BIM.”

Micro (n = 35) and small (n = 18) firms show a concentration at the lower end of the adoption spectrum: 30.6% of micro firms (13 out of 35) and 27.8% of small firms (5 out of 18) report no BIM use. Additionally, the majority—48.6% of micro (17/35) and 44.4% of small firms (8/18)—use BIM solely during the design phase. Only a marginal share extends BIM to construction (8.6% of micro, 3/35; 16.7% of small, 3/18) or applies it across the entire lifecycle (5.7% of micro, 2/35; 11.1% of small, 2/18). These patterns reflect persistent barriers to digital uptake among smaller enterprises, including limited internal capacity, lack of specialized training, and limited exposure to complex project environments where advanced BIM integration is either required or incentivized.

Medium-sized firms (n = 14) exhibit a more balanced adoption profile. While 28.6% (4/14) report no BIM use and 28.6% (4/14) use it only for design, a notably higher share (28.6%, 4/14) apply BIM across both design and construction, and 14.3% (2/14) report full lifecycle BIM use. This broader distribution may reflect a critical mass of internal resources and project complexity that justifies a more advanced BIM strategy.

Interestingly, large enterprises (n = 29) do not show the highest levels of Lifecycle BIM adoption. Only 13.8% (4/29) report using BIM across the lifecycle, a lower share than among medium-sized firms. Although their rates of “No use” are somewhat lower (27.6%, 8/29), a considerable portion remains concentrated in the “Design only” (31.0%, 9/29) and “Design + Construction” (27.6%, 8/29) categories.

This somewhat counterintuitive pattern may be explained by several structural and market-related factors. Many large firms in the sample are contractors, operating in contexts where Lifecycle BIM is not routinely required—such as public tenders or low-margin projects. Moreover, such firms often exhibit siloed organizational structures, where BIM is deployed in discrete departments but not extended across the entire asset lifecycle. Legacy systems, fragmented digital ecosystems, and uneven client-side demand further inhibit full integration. As such, large firm capacity does not automatically translate into advanced digital implementation.

These findings on the intensity of BIM usage by company size confirm the presence of structural barriers to digital transformation, particularly among smaller firms. Building on these patterns, the next figure (

Figure 4) shifts focus on preferred training formats that could address identified capacity gaps—especially in the context of integrating Circular Economy (CE), Agile Project Management (APM), and BIM approaches.

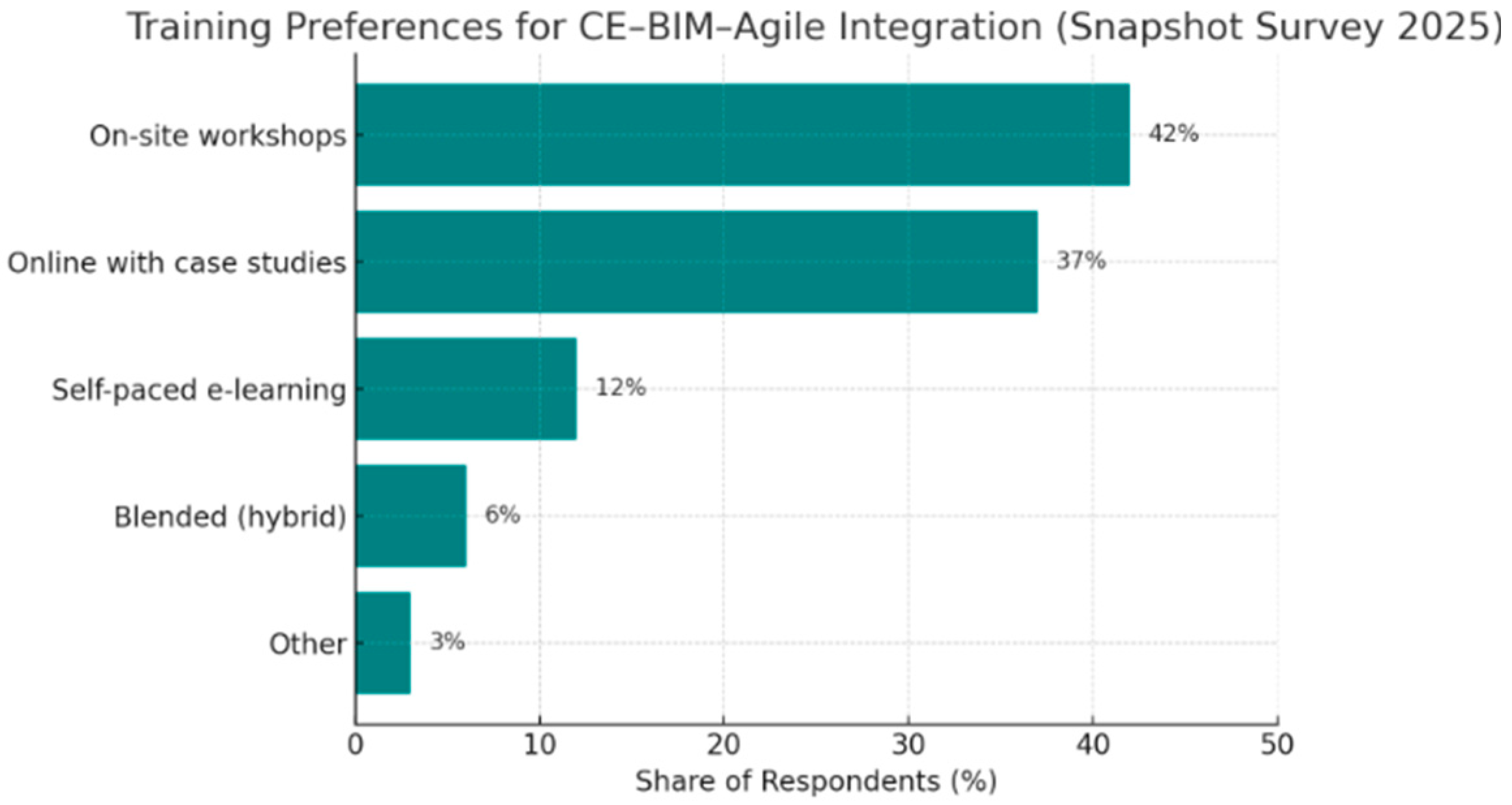

Therefore,

Figure 4 presents the distribution of training preferences for integrating Circular Economy (CE), Building Information Modeling (BIM), and Agile Project Management (APM), based on data from the CE-APM-BIM Survey 2025 (n = 98). Respondents were asked to indicate their preferred learning formats from a predefined set of options commonly used in professional training. A clear majority of respondents (94%, n = 92) expressed interest in participating in some form of structured training. Among them, 42% (n = 41) favored on-site workshops, reflecting a preference for direct, hands-on learning with opportunities for peer interaction. An additional 37% (n = 36) preferred online training formats that include real-world case studies, emphasizing the demand for applied knowledge contextualized to construction practice. These top-ranked formats indicate that SMEs value experiential and practical approaches over purely theoretical instruction.

By comparison, 12% (n = 12) of respondents opted for self-paced e-learning, and 6% (n = 6) indicated a preference for blended (hybrid) learning models. A small number (3%, n = 3) selected other formats. Importantly, only 6% (n = 6) of participants reported no interest in training at all, highlighting an overwhelming latent readiness for capacity-building in the construction sector.

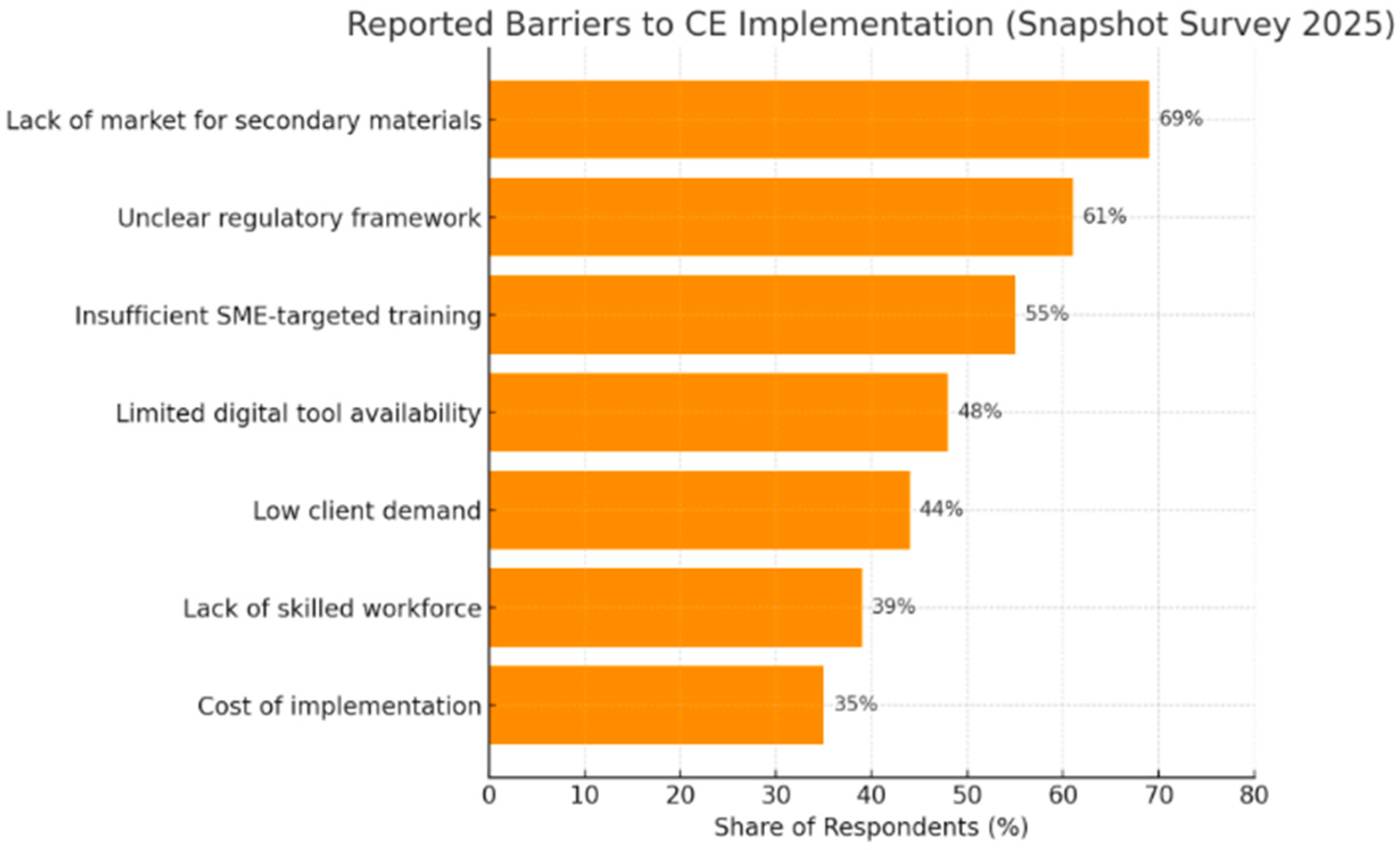

Figure 5 presents a multi-response analysis of the most reported barriers to implementing Circular Economy (CE) principles, derived from the CE-APM-BIM Survey 2025 (n = 98). Respondents were allowed to select multiple barriers, reflecting the multi-layered and systemic nature of CE implementation challenges in the construction sector.

The dominant constraint, reported by 69% of respondents (n = 68), was the absence of a functional and economically viable market for secondary construction materials. This finding points to a critical supply-side gap that inhibits material reuse, hinders planning reliability, and weakens business cases for circular procurement. Closely following, 61% of participants (n = 60) identified the lack of clear, consistent regulatory frameworks as a major impediment—underscoring the urgent need for policy harmonization and the integration of CE criteria into public procurement guidelines and building codes.

Equally concerning is the training gap: 55% of firms (n = 54) noted the absence of CE-specific educational offerings tailored to the realities of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), particularly those with limited internal capacity for innovation. Furthermore, 48% (n = 47) cited insufficient access to digital tools for material tracking, lifecycle monitoring, and circular design, emphasizing the technological barriers to operationalizing CE ambitions.

Additional factors include low client demand for circular construction solutions (44%, n = 43), shortages of skilled professionals capable of implementing CE principles (39%, n = 38), and the perceived high cost of transition measures (35%, n = 34). Collectively, these obstacles reveal a misalignment between strategic intent and operational feasibility, particularly for firms navigating volatile market conditions and fragmented supply chains.

These findings reinforce the qualitative insights from open-ended survey responses, which stressed the need for practical, regionally adapted tools, realistic implementation guidance, and capacity-building initiatives tailored to the specific constraints of Mediterranean construction ecosystems. Respondents repeatedly called for training formats that link CE concepts with BIM-enabled workflows and agile coordination practices, delivered through peer-based, experiential formats such as workshops and case-based online modules.

Taken together, the results of the CE-APM-BIM survey suggest a sector poised for transformation but constrained by infrastructure, policy gaps, and capacity deficits. These insights underscore the importance of integrative pilot projects and cross-sectoral knowledge exchange as mechanisms for accelerating uptake across the Mediterranean construction landscape.

5. Discussion

The findings from both the BLOOM project and the CE-APM-BIM survey 2025 converge on a clear insight: awareness of Circular Economy (CE), Building Information Modelling (BIM), and Agile Project Management (APM) is high among construction-sector SMEs, but implementation remains low. In the BLOOM dataset, over 75% of respondents reported familiarity with CE concepts, and 63% indicated some level of BIM use—yet only 19% demonstrated readiness to integrate CE, BIM, and APM simultaneously. Similarly, in the primary CE-APM-BIM survey, 86% acknowledged the strategic potential of integration, yet only 21% used BIM beyond the design phase, and a mere 12% reported any agile project delivery experience.

Despite differing regional and institutional contexts, both data sources highlight strikingly similar barriers to implementation: lack of a viable market for secondary construction materials, unclear regulatory frameworks, and limited access to SME-adapted training. These converging findings reinforce the reliability of the observed patterns and underscore the systemic nature of the transition gap in circular construction.

BIM emerges as a critical enabler in the shift toward integrated circular and agile construction practices. Analysis of both datasets shows a positive correlation between BIM maturity and CE–APM readiness. In the BLOOM data, firms with advanced BIM use were significantly more likely to report openness to agile processes and CE-aligned experimentation. This suggests that digital maturity, particularly in lifecycle data modelling, enhances a firm’s capacity to engage with regenerative practices.

Nevertheless, the CE-APM-BIM survey revealed that such digital maturity is rare: only one in five firms uses BIM beyond the design phase. Even among large firms, Lifecycle BIM remains limited (13.8%), and 27.6% of large respondents reported no BIM use at all. This highlights a critical bottleneck: while BIM may be a prerequisite for advanced CE implementation, it is not yet widely adopted in practice, and scaling its use across the SME landscape requires targeted intervention.

Together, the surveys reveal a fragmented SME landscape—characterized by high conceptual alignment but inconsistent operational capacity. The BLOOM results highlight substantial variation in CE maturity across firms, while the CE-APM-BIM Survey confirms strong demand for support: 94% of respondents expressed interest in integrated training, with a strong preference for applied, experiential formats.

This suggests that SMEs are not resistant to change but rather lack the structural support to engage meaningfully in transformation. The findings point out four strategic imperatives:

Accessible tools that simplify CE–BIM–APM application in real projects;

Targeted, hands-on training rooted in practical scenarios and regional realities;

A transparent regulatory framework that reduces uncertainty and aligns procurement criteria with CE goals;

Pilot projects and demonstration sites that showcase feasible, scalable models of circular construction.

These imperatives align closely with the BLOOM project’s proposed roadmap, which emphasize the value of community-based experimentation and cross-sectoral knowledge exchange.

Given the aligned findings, there is a clear rationale for advancing a unified conceptual framework that brings together CE, BIM, and APM as mutually reinforcing pillars of regenerative construction. CE provides long-term strategic direction, BIM offers the technical infrastructure for data-driven decision-making, and APM introduces the agile mindset required to coordinate uncertainty and drive iterative innovation.

This discussion lays the groundwork for the framework proposed in the next section. The empirical insights validate the need for an integrated model that is simple enough to be actionable for SMEs, yet robust enough to address the complexity of transitioning from linear to circular construction. The CE–BIM–APM framework is thus offered not as a theoretical abstraction, but as a practical response to the challenges and potentials documented across two interrelated studies.

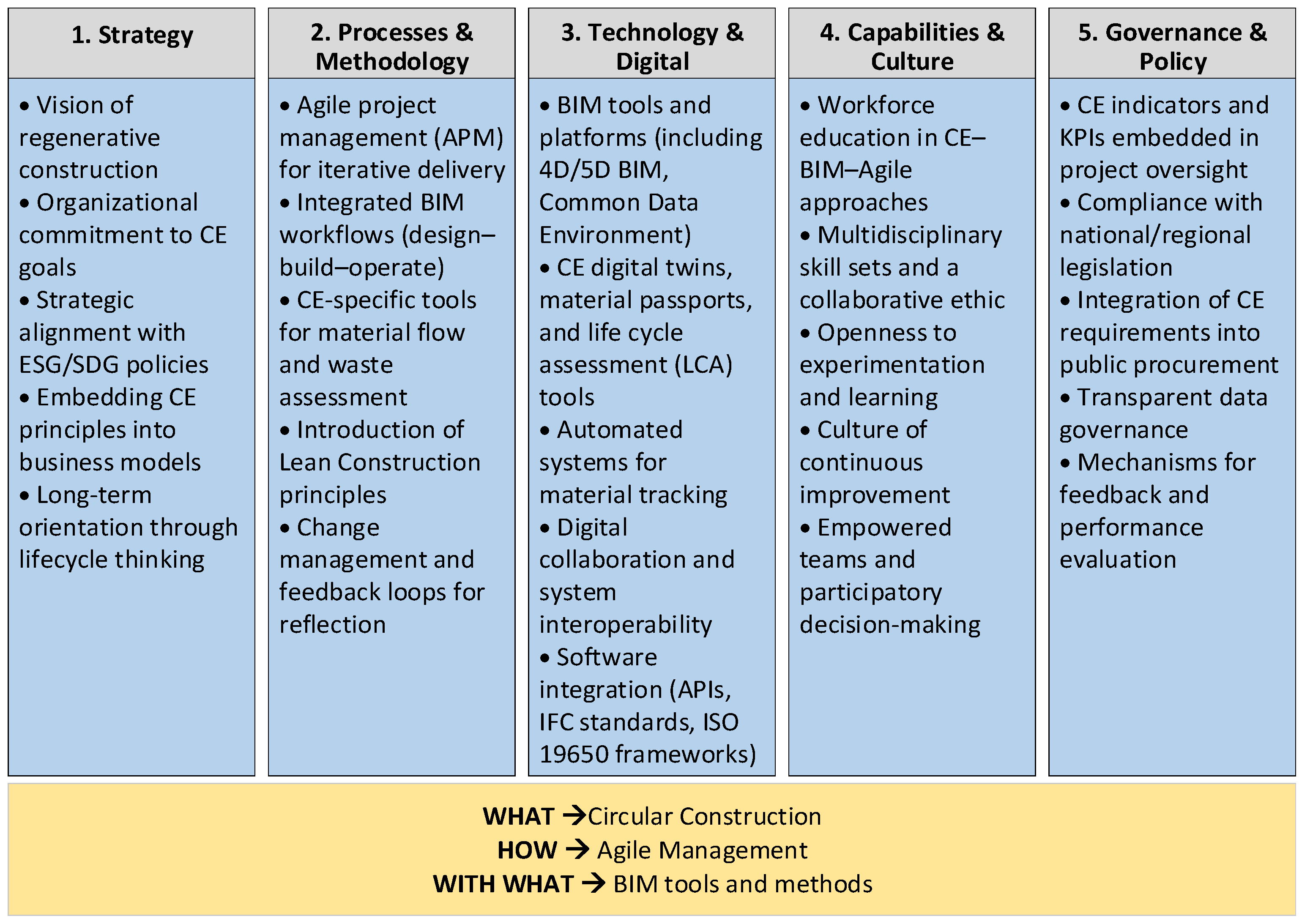

6. The CE-APM-BIM Integration Framework

Building on the conducted research and state-of-the-art, this section introduces an integrated framework designed to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in their transition toward regenerative construction practices. The framework synthesizes Circular Economy (CE) as the strategic “why,” Agile Project Management (APM) as the procedural “how,” and Building Information Modeling (BIM) as the digital “with what.” It positions these elements within five core pillars essential for enabling systems-level transformation in the construction sector: Strategy, Processes & Methodology, Technology & Digital Infrastructure, Capabilities & Culture, and Governance & Policy.

As demonstrated by both datasets, conceptual awareness of CE, BIM, and APM is widespread, but implementation lags due to fragmented systems, insufficient training, and regulatory and technological uncertainty. The surveys also highlight a strong latent demand for transformation: over 80% of SMEs believe in the strategic value of integration, and nearly all respondents expressed interest in structured, practice-oriented learning formats. Yet, the key bottlenecks—low BIM maturity, unclear CE regulation, and weak agile readiness—suggest the need for a unified but flexible approach that enables SMEs to engage in transformative practices even under resource constraints. The proposed CE–APM–BIM Integration Framework addresses this by offering a holistic view of enablers and interdependencies across organizational layers.

The framework is structured along five interdependent pillars:

Strategy – defining long-term direction and embedding CE values into organizational vision and business models.

Processes & Methodology – operationalizing CE through agile project delivery, BIM-enabled workflows, and lean construction tools.

Technology & Digital Infrastructure – deploying digital enablers (e.g., 4D/5D BIM, material passports, digital twins) to support circular data management and collaboration.

Capabilities & Culture – fostering a multidisciplinary, empowered, and learning-oriented workforce through targeted training and inclusive governance.

Governance & Policy – embedding CE criteria into procurement, aligning projects with regulatory mandates, and ensuring transparency through KPIs and performance feedback mechanisms.

The framework is visually represented in

Figure 6, with vertical pillars depicting enabling dimensions and a horizontal layering that aligns CE (what to achieve), APM (how to work), and BIM (with what to enable). This structure ensures conceptual clarity while allowing for contextual customization based on firm size, market maturity, and project typology.

Each of the five pillars of the CE–APM–BIM Integration Framework comprises actionable and interrelated components that enable meaningful progress toward circular and regenerative construction practices. The Strategy pillar encompasses the establishment of key performance indicators (KPIs) aligned with circular economy objectives, integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) considerations, and the institutionalization of lifecycle thinking within business models and long-term planning. This strategic orientation ensures that CE principles are embedded not merely as project-level add-ons but as core organizational values guiding investment, procurement, and innovation.

Within the Processes and Methodology dimension, the framework advocates for the operationalization of CE through the integration of assessment tools—such as material flow analysis and waste audits—into agile project sprints and iterative planning cycles. By doing so, sustainability objectives become part of routine decision-making rather than isolated assessments. Agile methods facilitate adaptive management, allowing teams to reflect, learn, and improve continuously throughout the project lifecycle.

The Technology and Digital Infrastructure pillar is anchored in the deployment of interoperable platforms that support real-time collaboration, data transparency, and lifecycle information management. Tools such as 4D/5D BIM, digital twins, material passports, and life cycle assessment (LCA) systems—underpinned by openBIM principles and ISO 19650 frameworks—enable comprehensive data-driven coordination across project phases and stakeholder boundaries.

In terms of Capabilities and Culture, the framework emphasizes the importance of developing a multidisciplinary workforce equipped with the skills and mindsets necessary to navigate CE, agile, and BIM domains simultaneously. Upskilling efforts should include blended learning formats, peer-to-peer exchanges, and structured support for agile team formation. Creating a culture that values experimentation, feedback, and continuous improvement is critical to sustaining innovation over time.

Finally, the Governance and Policy pillar highlights the need for transparent and consistent rules that support CE implementation. This includes embedding CE-relevant indicators and KPIs into project oversight, ensuring compliance with national and regional legislation, and linking CE requirements to public procurement mechanisms. Establishing robust data governance practices and feedback loops further enhances accountability and learning at both organizational and system levels.

Taken together, these pillars form a coherent, adaptable framework capable of guiding pilot projects, informing policy design, and structuring capacity-building programs tailored to the specific needs and constraints of SMEs. The modular nature of the framework accommodates varying starting points and levels of maturity, providing a clear yet flexible trajectory toward higher integration of circular, agile, and digital principles in construction.

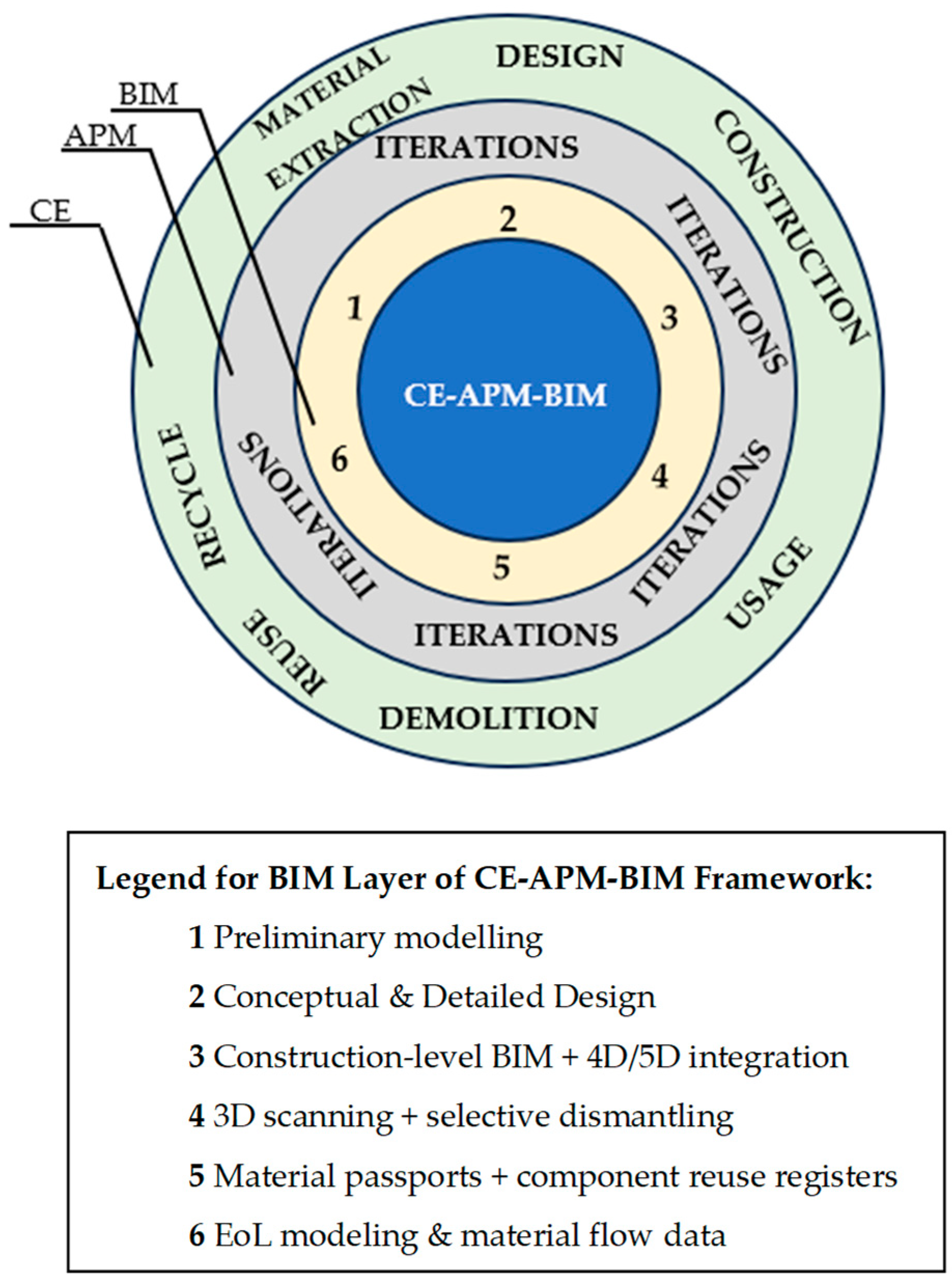

While

Figure 6 outlines the five structural pillars necessary to enable the integration of Circular Economy (CE) goals, Agile methodologies, and BIM tools in construction SMEs, the conceptual framework remains inherently systemic and multi-layered. To further clarify the operational relationships between these components,

Figure 7 offers a dynamic representation of the CE–Agile–BIM integration process.

This process-oriented diagram emphasizes the functional interaction among strategic principles (CE), delivery methods (Agile), and enabling technologies (BIM). It visualizes how circular objectives are embedded into iterative workflows, supported by BIM-based tools and guided by agile procedures. Moreover,

Figure 7 illustrates the procedural logic of the CE–APM–BIM integration framework, highlighting how iterative loops operate across all phases of the construction lifecycle—from material sourcing to end-of-life (EoL) processes. In this context, iterations represent cyclical processes of improvement, adaptation, and feedback that occur within each stage of the circular economy (CE) loop. These are enabled by agile project management methodologies and supported by Building Information Modeling (BIM) tools and workflows.

Together, the two figures provide a complementary view—

Figure 6 frames the structural enablers, while

Figure 7 captures the procedural logic that drives integrated project execution across the lifecycle.

Phase-specific interpretation of iterations in the CE–APM–BIM framework:

Iterative cycles involve evaluating alternative material sourcing strategies with lower environmental impact, integrating simulations of secondary material availability, and aligning with material passports through BIM platforms. Agile methods facilitate rapid testing of different procurement and reuse scenarios.

- 2.

Design

Iterations in the design phase are supported by BIM-enabled parametric modeling (e.g., 4D/5D BIM), which fosters real-time collaboration between architects, engineers, and contractors. Agile sprints promote rapid testing of CE strategies such as modularity, disassembly potential, and design for adaptability.

- 3.

Construction

During construction, iterative adjustments are driven by digital monitoring tools that enable real-time optimization of workflows. BIM models are updated continuously, and agile coordination ensures flexibility in execution plans as materials, site conditions, or CE constraints evolve.

- 4.

Usage

Iterations in the usage phase relate to continuous performance monitoring via digital twins and sensor-based systems. Feedback from building operation informs maintenance strategies aimed at extending the lifecycle of components and systems, in alignment with CE principles.

- 5.

Reuse

BIM models, enriched during the usage phase, enable identification of elements suitable for disassembly and reuse. Iterative cycles here involve feasibility assessments, market alignment, and logistic planning for the reintegration of components into new value chains.

- 6.

End-of-Life (EoL: Demolition, Recycle, Reuse)

In the final phase, iterative assessments support decisions around selective demolition, sorting strategies, and material recovery optimization. BIM facilitates data-driven material inventories, while agile principles ensure adaptive decision-making in response to site conditions and regulatory factors.

7. Conclusions

This study contributes to the growing discourse on sustainable transformation in the construction sector by presenting and empirically supporting an integrated CE–APM–BIM framework. Grounded in two complementary survey datasets across Mediterranean SMEs, the findings confirm a significant strategic awareness of circularity, agility, and digitalization, yet highlight persistent implementation barriers—particularly in agile practices and full lifecycle BIM adoption. The proposed framework synthesizes five key pillars—Strategy, Processes, Technology, Capabilities, and Governance—to provide a structured, modular foundation for SMEs navigating the shift toward regenerative construction. It positions Circular Economy (CE) as the strategic anchor, Agile Project Management (APM) as the procedural enabler, and Building Information Modeling (BIM) as the digital infrastructure necessary for effective integration across the project lifecycle.

By explicitly connecting CE goals with agile operational models and BIM-based digitalization, the framework provides a structured response to long-standing fragmentation in sustainability innovation. It reflects international best practices (e.g., Level(s), ISO 19650, SDGs) while remaining adaptable to regional realities, especially in the Mediterranean and Central European context. Moreover, the framework supports cross-sectoral alignment: it can be used not only by construction firms but also by educators, policymakers, and digital tool developers to shape interventions that reinforce each other. Its modular structure allows for phased implementation, ensuring that even resource-constrained SMEs can engage in meaningful circular innovation.

The empirical evidence reinforces that while SMEs are motivated to engage in sustainability transitions, they remain constrained by training gaps, regulatory ambiguity, and digital immaturity. To overcome these systemic obstacles, the study emphasizes the need for policy-aligned pilot projects, practical training formats, and incentive-based digital toolkits—especially adapted to the SME context.

Limitations and Future Work

This research is subject to several limitations. First, the survey sample, while diverse and well-targeted, is not statistically representative and may reflect a higher-than-average level of innovation readiness. Second, the framework has not yet been piloted in real-world settings, so its operational feasibility across project types and regulatory contexts remains to be tested. Third, cultural factors influencing agile adoption in construction were only indirectly captured.

Future research should focus on empirical validation of the framework through pilot implementations, longitudinal studies, and cross-national comparisons. Special attention should be given to the role of clients, procurement processes, and certification systems in enabling or hindering the CE–APM–BIM integration. Furthermore, developing open-access training modules and digital maturity assessment tools would be crucial next steps to support SME readiness. By advancing this framework, we aim to inform both practitioners and policymakers on scalable, systemic approaches to unlocking circularity through agile, digitally supported construction processes.

Funding

This research received no external funding. However, part of the initial data collection was conducted within the framework of the BLOOM project, supported by the Norway Grants 2014–2021 under the “Business Development and Innovation Croatia” program. The results from the BLOOM survey (n = 153) served as a foundation for the broader CE–APM–BIM research presented in this paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its focus on anonymous expert surveys with no collection of personal, sensitive, or health-related data. The study involved voluntary participation of professionals in the construction sector and did not include any vulnerable populations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation in the surveys was entirely voluntary, and all responses were collected anonymously without any personally identifiable information.

Data Availability Statement

The aggregated survey data and synthesized indicators supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to participating in confidentiality agreements, raw individual-level data is not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all respondents who participated in both the BLOOM and CE-APM-BIM 2025 surveys. Special thanks are extended to the Faculty of Civil Engineering, University of Zagreb, for providing access to the necessary research infrastructure (including computational equipment and software tools) that supported the technical aspects of the study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4, 2024) for technical assistance in paraphrasing, data visualization refinement, and layout suggestions. The author has critically reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the final content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEC |

Architecture, Engineering and Construction |

| APM |

Agile Project Management |

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling / Modelling |

| BLOOM |

Project acronym: empowering construction SMEs for the circular economy; supported by the Norway Grants 2014–2021 under the Business Development and Innovation Croatia Programme |

| CDW |

Construction and Demolition Waste |

| CE |

Circular Economy |

| DfMA |

Design for Manufacture and Assembly |

| EEA |

European Economic Area |

| EoL |

End-of-Life |

| ERP |

Enterprise Resource Planning |

| ESG |

Environmental, Social and Governance |

| EU |

European Union |

| FF&E |

Furniture, Fixtures and Equipment |

| IEA |

International Energy Agency |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| KPI |

Key Performance Indicator |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| LD |

Linear Dichroism (vjerojatno pogrešno uneseno, nema veze s temom)

|

| Minergie-ECO |

Swiss building sustainability certification standard combining energy efficiency and ecological quality |

| RhinoCircular |

A design tool for real-time circularity feedback based on Rhino/Grasshopper platform |

| SME |

Small and Medium-sized Enterprise |

| TLA |

Three-Letter Acronym (generička kratica, nebitna za sadržaj)

|

| UNEP |

United Nations Environment Programme |

References

- UNEP (2022) 2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme. https://globalabc.org/resources/publications.

- IEA (2023) Buildings: Tracking Clean Energy Progress. International Energy Agency. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/buildings.

- European Commission (2019) The European Green Deal. COM(2019) 640 final. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640.

- European Commission (2020a) Circular Economy Action Plan: For a cleaner and more competitive Europe. COM(2020) 98 final. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0098.

- European Commission (2020b) A Renovation Wave for Europe – Greening our buildings, creating jobs, improving lives. COM(2020) 662 final. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0662.

- European Commission (2021) EU taxonomy for sustainable activities. Available at: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en.

- González, M.J. , García Navarro, J. and Mainini, A.G. (2022) ‘BIM-based circular strategies for design and construction: A systematic review’. Buildings 2022, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. , Park, J. and Lee, S. (2023) ‘Integration of BIM and material passports for circular construction: A case study’, Buildings, 13(2), 297. [CrossRef]

- Denicol, J. , Davies, A. and Krystallis, I. (2020) ‘What are the causes and cures of poor megaproject performance? A systematic literature review and research agenda’, Project Management Journal, 51(3), pp. 328–345. [CrossRef]

- Vourc’h, A. , Sgaravatto, B. and Zimmermann, E. (2022) ‘SMEs and Circular Economy: What Do We Know? A Literature Review’, Buildings, 12(12), 2106. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat (2023) Generation of waste by economic activity and households. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Waste_statistics.

- EEA and Norway Grants (2024) BLOOM Project – Building Learning Outcomes for Occupations in the Circular Construction. Internal dataset.

- Martens, B. , Aelenei, D. and Silva, S.M. (2022) ‘Agile BIM-based platform to support material reuse in circular construction’, Sustainability, 14(20), 13208. [CrossRef]

- Bjørberg, S. , Thomsen, A., Jensen, P.A. and Re Cecconi, F. (2023) ‘Linking circular economy and agile principles in facility management’, Journal of Facilities Management, 21(3), pp. 272–288. [CrossRef]

- Koskela, L. and Howell, G. (2002) ‘The underlying theory of project management is obsolete’, Proceedings of the PMI Research Conference, 293–302.

- Enembreck, F. , Veras, A.L.M., Sato, L.M. and Graciolli, O.D. (2024) ‘Agile frameworks in circular built environments: theoretical intersections and practice-led challenges’, Sustainability, 16(3), 1235. [CrossRef]

- Underwood, J. , Shelbourn, M., Fleming, A., Heywood, J., & Roberts, I. (2018). Streamlining a Design, Manufacture, and Fitting Workflow Within a UK Fit-Out SME: A BIM Implementation Case Study (pp. 242–266). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Naneva, A. (2022). greenBIM, a BIM-based LCA integration using a circular approach based on the example of the Swiss sustainability standard Minergie-ECO. E3S Web of Conferences, 349, 10002. [CrossRef]

- greenBIM, a BIM-based LCA integration using a circular approach based on the example of the Swiss sustainability standard Minergie-ECO. (n.d.

- Heisel, F. , & McGranahan, J. (2024). Enabling Design for Circularity with Computational Tools (pp. 97–110). Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Kuzminykh, A. , Granja, J., Parente, M., & Azenha, M. (2024). Promoting circularity of construction materials through demolition digitalisation at the preparation stage: Information requirements and openBIM-based technological implementation. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 62, 102755. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, V. F. , & Góes, T. M. (2021). Contribuição do BIM para o desenvolvimento da Economia Circular no ambiente construído: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. 30. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , van den Berg, M., Voordijk, H., & Adriaanse, A. M. (2023). Circularity Assessment Across Project Phases in a Bim Environment. [CrossRef]

- Kakkos, E. , & Hischier, R. (2022). Paving the way towards circularity in the building sector. Empa’s Sprint Unit as a beacon of swift and circular construction. IOP Conference Series, 1078(1), 012009. [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E. , Ünal, E., Urbinati, A., Chiaroni, D., & Manzini, R. (2019). Value creation in circular business models: the case of a US small medium enterprise in the building sector. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 146, 291–307. [CrossRef]

- Mamoghli, S. , & Cassivi, L. (2019). Agile ERP Implementation: The Case of a SME. International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, 188–196. [CrossRef]

- Enembreck, F. L. P. , Freitas, M. do C. D., Bragança, L., & Tavares, S. F. (2023). Potential Synergy Between Agile Management and the Mindset of Circular Economy in Construction Projects (pp. 239–248). Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).