Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of the New Chalcogenides from the Ge-Te-Cu System and Preparation of the Bilayer Structure

2.2. Methods Used for Characterization of the Synthesized New Chalcogenides and Measuring the Kinetic of the Photoinduced Birefringence

2.3. Optical Setup for Measuring the Photo-Induced Birefringence

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Z.; Clima, S.; Garbin, D.; Degraeve, R.; Pourtois, G.; Song, Z.; Zhu, M. Chalcogenide Ovonic Threshold Switching Selector. Nanomicro Lett. 2024, 11, 16–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, T.; Ovshinsky, S. R. ; Phase-Change Optical Storage Media. Photo-Induced Metastability in Amorphous Semiconductors; Kolobov A.V.; 1st ed.; Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, 2003; pp. 310–326.

- Wuttig, M.; Yamada, N. Erratum: Phase-change materials for rewriteable data storage. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 1004–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, A. Advanced technology and systems of cross point memory. International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020, 24.1.1–24.1.4.

- Yamada, N.; Ohno, E.; Akahira, N.; Nishiuchi, K.; Nagata, K.; Takao, M. High Speed Overwritable Phase Change Optical Disk Material, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1987, 26, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, H.; Harigaya, M.; Nonoyama, O.; Kageyama, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Yamada, K.; Deguchi, H.; Ide, Y. Completely Erasable Phase Change Optical Disc II: Application of Ag-In-Sb-Te Mixed-Phase System for Rewritable Compact Disc Compatible with CD-Velocity and Double CD-Velocity. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1993, 32, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorini; A. D.; Chèze, C.; García, I. L.; Petrucci, C.; Bertelli, M.; Riva, F. R.; Prili S.; Privitera S. M. S.; Buscema M.; Sciuto, A.; Franco, S.; D'Arrigo G.; Longo, M.; Simone, S.; Mussi, V.; Placidi, E.; Cyrille, M-C.; Tran, N-P.; Calarco, R.; Arciprete, F. Growth, electronic and electrical characterization of Ge-rich Ge–Sb–Te alloy. Nanomater. 2022, 13.

- Petroni, E.; Allegra, M.; Baldo, M.; Laurin, L.; Andrea, S.; Favennec, L.; Desvoivres, L.; Sandrini, J.; Boccaccio, C.; Le-Friec, Y.; Ostrovsky, A.; Gouraud, P.; Bonnevialle, A.; Ranica, R.; Redaelli, A. Study of Ge-Rich Ge–Sb–Te device-dependent segregation for industrial grade embedded phase-change memory. PSS RRL, 2024, 18.

- Zhou, X.; Zhou, X.; Xia, M.; Rao, F.; Wu, L.; Li, X.; Song, Z.; Feng, S.; Sun, H. Understanding phase-change behaviors of carbon-doped Ge2 Sb2 Te5 for phase-change memory application. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 14207–14214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovchak, R.; Plummer, J.; Kovalskiy, A.; Holovchak, Y.; Ignatova, T.; Trofe, A.; Mahlovanyi, B.; Cebulski, J.; Krzeminski, P.; Shpotyuk, Y.; Boussard-Pledel, C.; Bureau, B. Phase-change materials based on amorphous equichalcogenides. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, L. K.; Sripathi, Y.; Reddy G., B. Material science aspects of phase change optical recording. Bull. Mater. Sci., 1995, 18, 725–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Shen, X.; Nie, Q.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Fu, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, T.; Dai, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, R. Te-based chalcogenide films with high thermal stability for phase change memory. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 093514–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Koike, J. Optical contrast and laser-induced phase transition in GeCu2Te3 thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongol, M.; AbouZied, M.; Gamal, G.A.; El-Denglawey, A. Synthesis and the RDF fine structure of Ge0. 15Te0.78Cu0.07 bulk alloy. Optik, 2016, 127, 8186–8193. [Google Scholar]

- Skelton, J. M.; Kobayashi, K.; Sutou, Y.; Elliott, S. R. Origin of the unusual reflectance and density contrasts in the phase-change material Cu2GeTe3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 224105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Sutou, Y.; Koike, J. Phase change characteristics in GeTe-CuTe pseudobinary alloy films. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 26973–26980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Sutou, Y.; Fons, P.; Shindo, S.; Kozina, X.; Skelton, J. M.; Kolobov, A.V.; Kobayashi, K. ; Electronic Structure of Transition-Metal Based Cu2GeTe3 Phase Change Material: Revealing the Key Role of Cu d Electrons. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 7440–7449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Ming; Chen L.; The microstructure and electrical and optical properties of Ge–Cu–Te phase-change thin films. Cryst Eng Comm, 2024, 26, 395–405.

- Mishra, S. P.; Krishnamoorthy, K.; Sahoo, R.; Kumar, A. Organic–inorganic hybrid polymers containing 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene and chalcogens in the main chain. J. Mater. Chem. 2006, 16, 3297–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbreders, A.; Teteris, J.; Kolobjonoks, V. Holographic recording in polymer composites of organic photochromes and chalcogenides, Sixth International Conference on Advanced Optical Materials and Devices, Riga, Latvia, 12. 11. 2008, 7142. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli, M.; Sfuncia, G.; De Simone, S.; Fattorini, A. D.; Calvi, S.; Mussi, V.; Arciprete, F.; Mio, A. M.; Calarco, R.; Longo, M. Stable chalcogenide Ge–Sb–Te heterostructures with minimal Ge segregation. Sci Rep, 2024, 14, 15713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberova-Buhova, N.; Nedelchev, L.; Stoykova, E.; Nazarova, D. Optical response evaluation of azopolymer thin solid films doped with gold nanoparticles with different sizes. J. Chem. Technol. Metall, 2022, 57, 671–675. [Google Scholar]

- Teteris, J.; Gertners, U. Optical field-induced surface relief formation on chalcogenide and azo-benzene polymer films, International Conference on Functional Materials and Nanotechnologies, Riga, Latvia, 17–20 April.

- Nazarova, D.; Nedelchev, L.; Sharlandjev, P.; Dragostinova, V. Anisotropic hybrid organic/inorganic (azopolymer/SiO2 NP) materials with enhanced photoinduced birefringence. Appl. Opt. 2013, 52, E28–E33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateev, G.; Nazarova, D.; Nedelchev, L. Increase of the Photoinduced Birefringence in Azopolymer Films Doped with TiO2 Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Technol. 2019, 3, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarova, D.; Nedelchev, L.; Stoykova, E.; Blagoeva, B.; Mateev, G.; Karashanova, D.; Georgieva, B.; Kostadinova, D. Photoinduced birefringence in azopolymer doped with Au nanoparticles. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1310, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

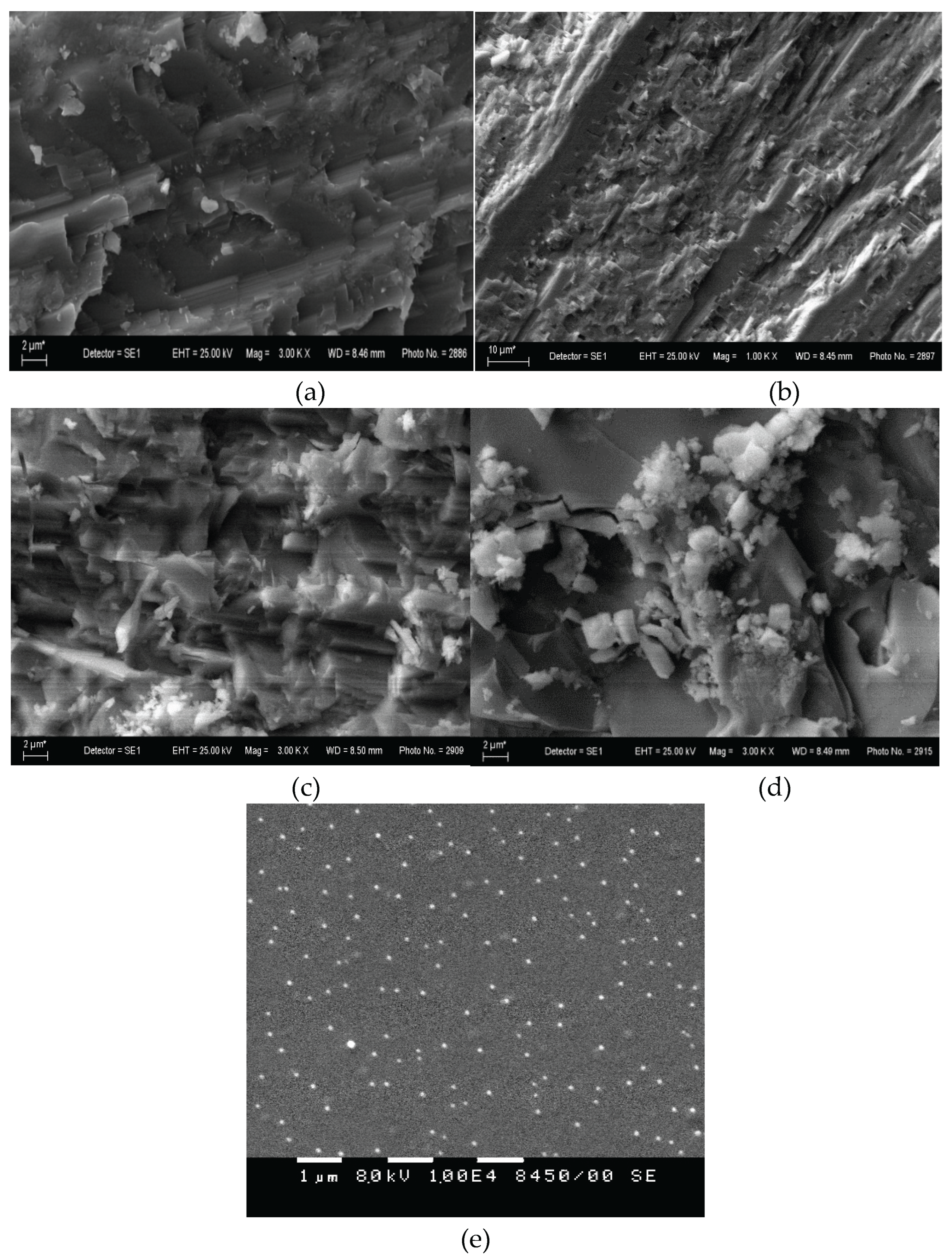

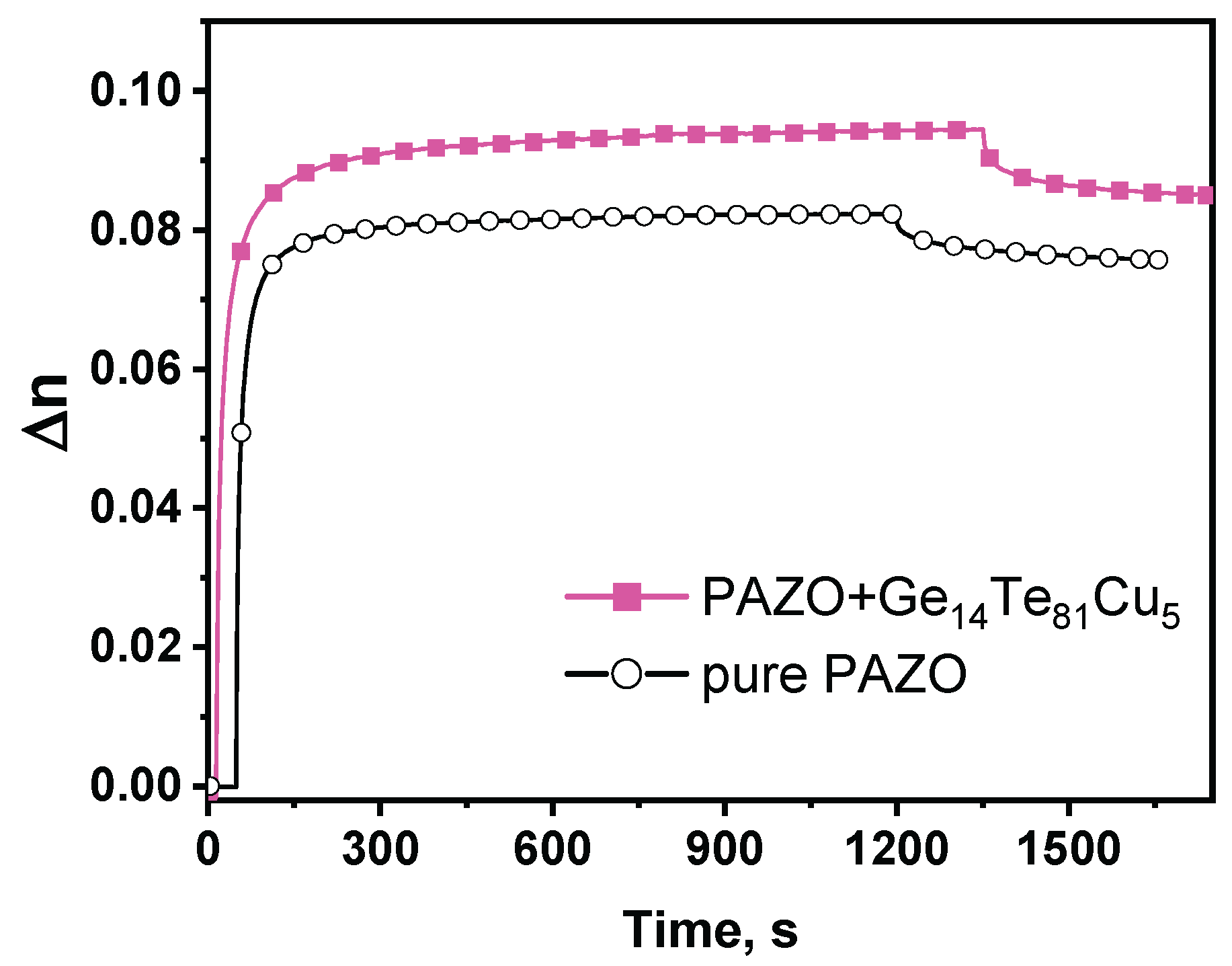

- Stoilova, A.; Dimov, D.; Trifonova, Y.; Lilova, V.; Blagoeva, B.; Nazarova, D.; Nedelchev, L. Preparation, structural investigation and optical properties determination of composite films based on PAZO polymer doped with GeTe4-Cu chalcogenide particles. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 95, 30301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, L.; Ramanujam, P.S. Polarization Holography; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

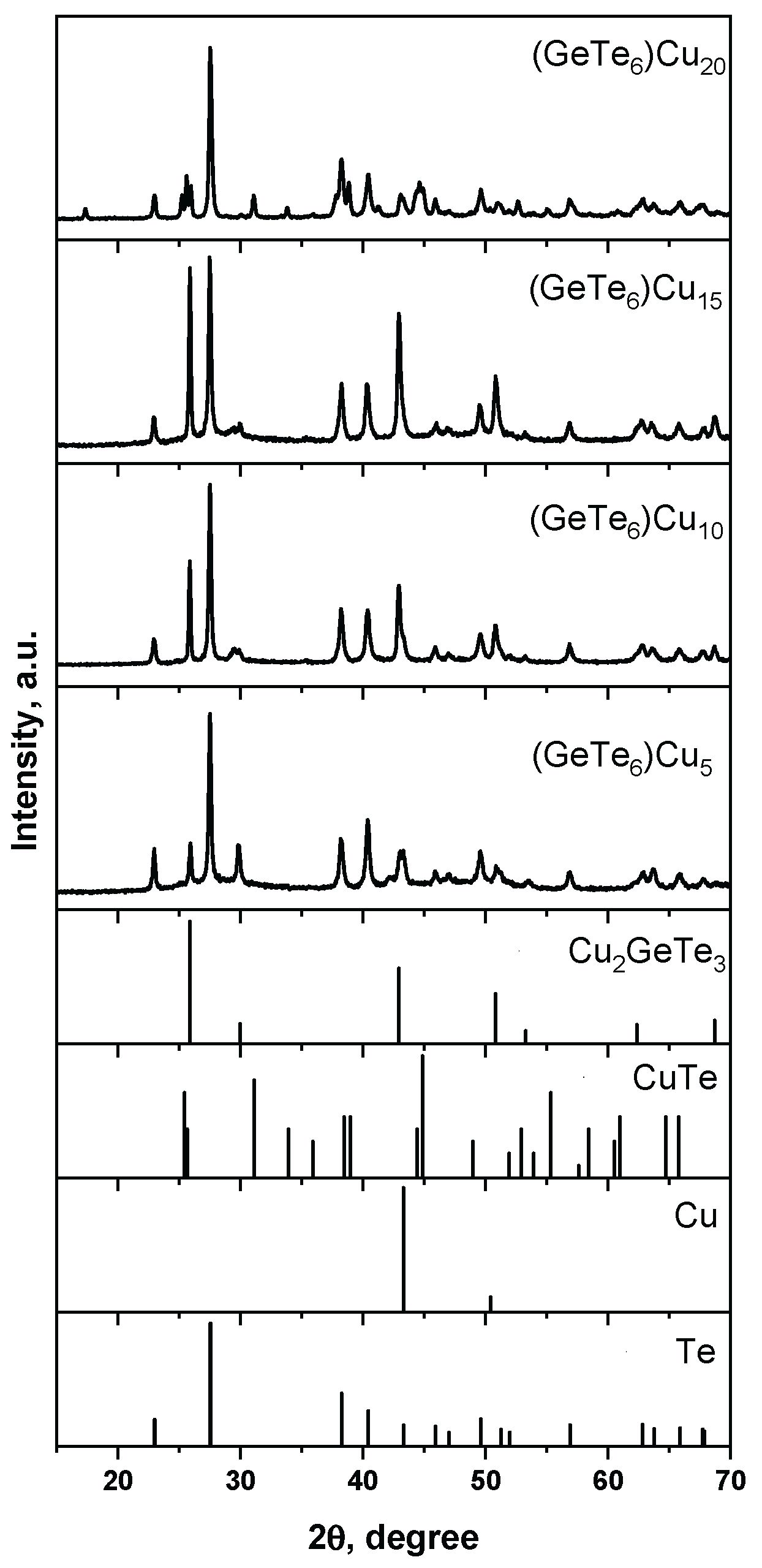

- Delgado, G.; Mora, A.; Pirela, M. Velásquez-Velásquez, A. ; Villarreal, M.; Fernández, B. Structural refinement of the ternary chalcogenide compound Cu2GeTe3 by X-ray powder diffraction. Phys. Stat. Sol. (a), 2004, 201, 2900. [Google Scholar]

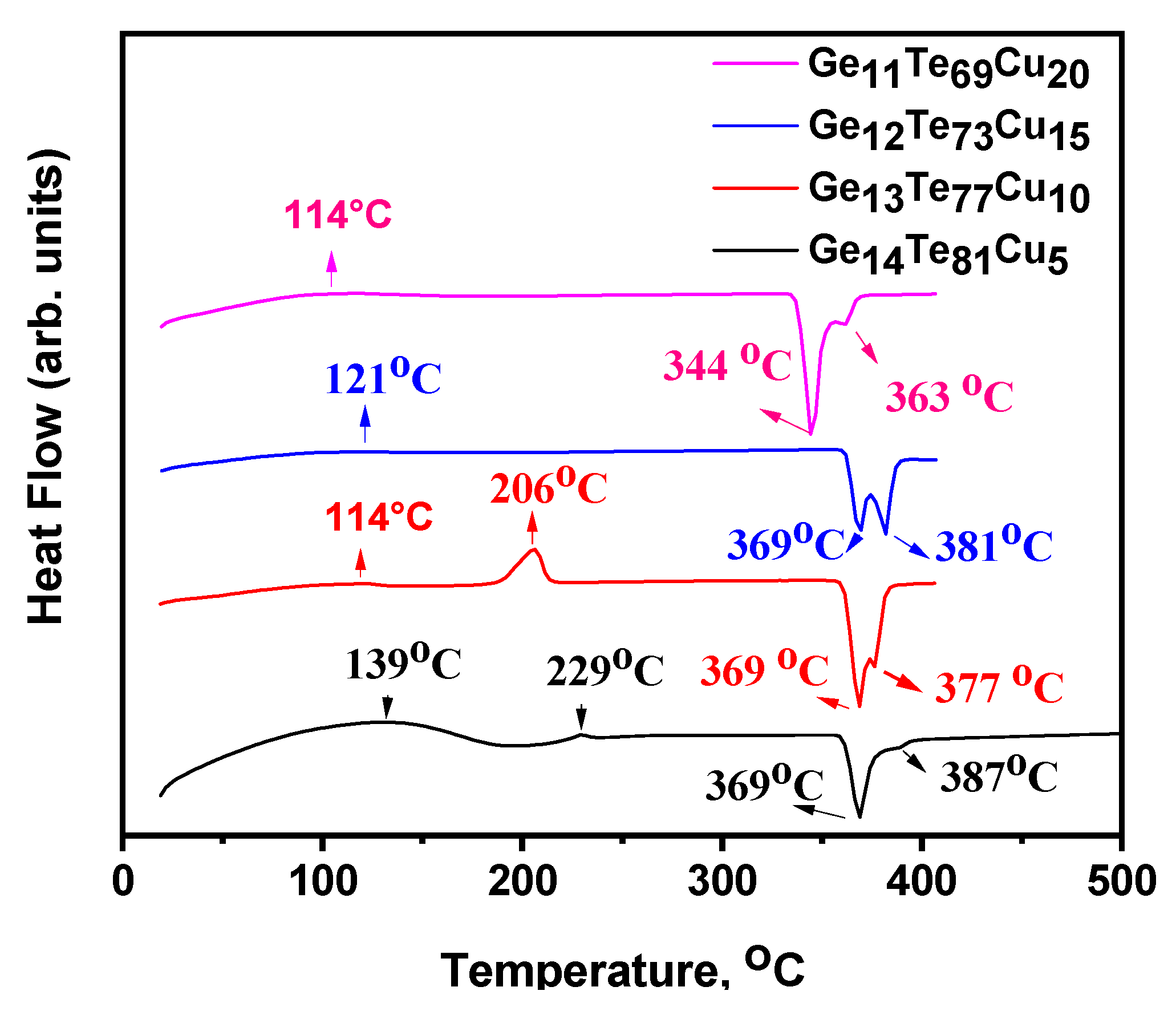

- Petkov, P.; Ilchev, P.; Ilcheva, V.; Petkova, T. ; Physico-chemical properties of Ge-Te-Ga glasses. J. Optoelectron. Adv. M. 2007, 9, 3093–3096. [Google Scholar]

- Tyona, M. D. A comprehensive study of spin coating as a thin film deposition technique and spin coating equipment, Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 2, 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Jemelka, J.; Palka, K.; Janicek, P.; Slang, S.; Jancalek, J.; Kurka, M.; Vlcek, M. Solution processed multi-layered thin films of Ge20Sb5S75 and Ge20Sb5Se75 chalcogenide glasses. Sci Rep, 2023, 13, 16609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarova, D.; Nedelchev, L.; Berberova-Buhova, N.; Mateev, G. Nanocomposite photoanisotropic materials for applications in polarization holography and photonics. Nanomaterials, 2023, 13, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krecmer, P.; Moulin, A. M.; Stephenson, R. J.; Rayment, T.; Welland, M. E.; Elliott S., R. Reversible Nanocontraction and Dilatation in a Solid Induced by Polarized Light. Sci. 1997, 277, 1799–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Ke.; Gotoh, T.; Nakayama, H. Anisotropic patterns formed in Ag–As–S ion-conducting amorphous semiconductor films by polarized light. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999, 75, 2256–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M. Disordered chalcogenide optoelectronic. J. Optoelectron. Adv. M. 2005, 7, 2189–2210. [Google Scholar]

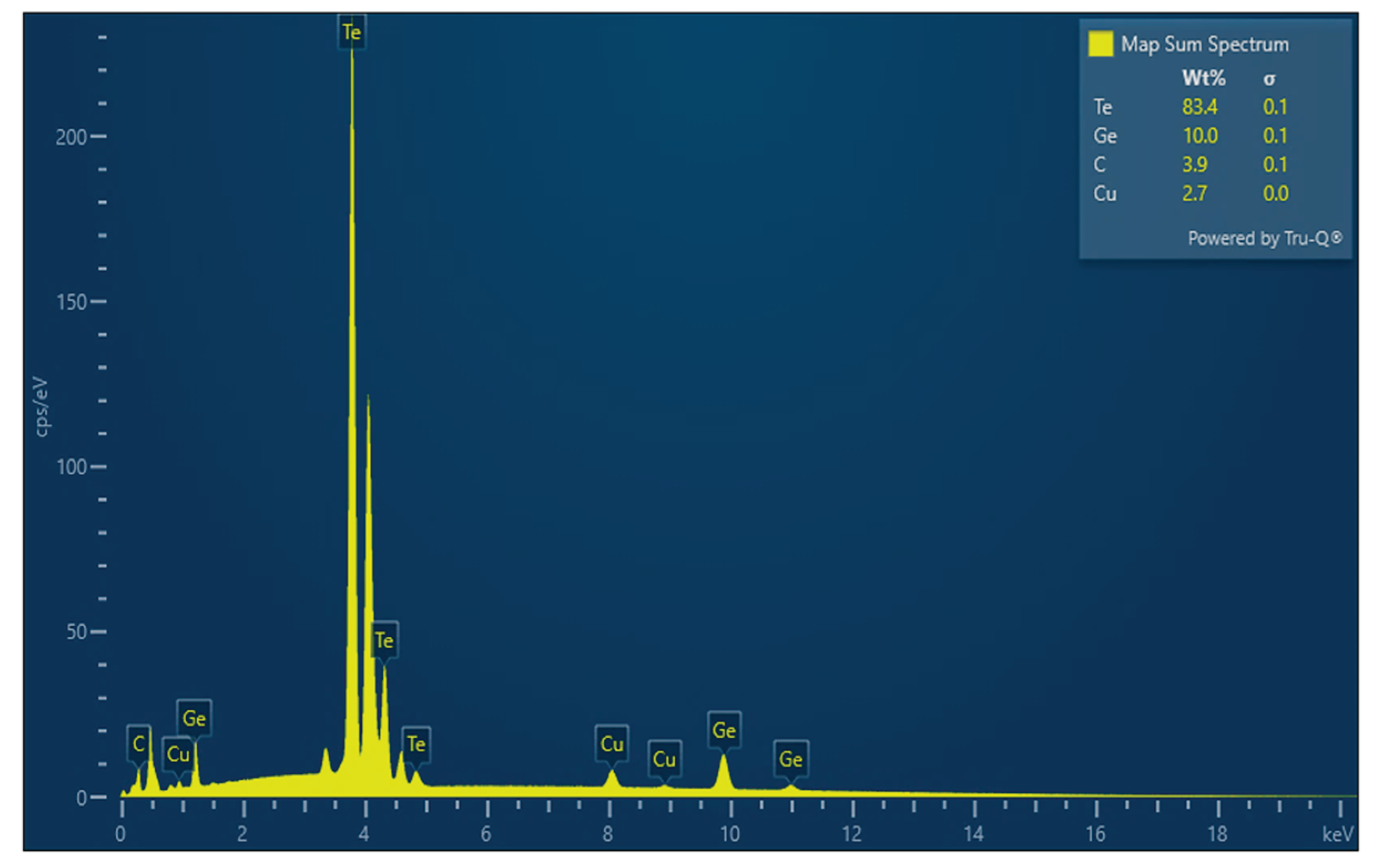

| Sample mol % |

Theoretically determined elemental concentration, wt. % | Elemental concentration determined by EDS, wt. % |

|---|---|---|

| Ge14Te81Cu5 |

Ge – 8.7 Te – 88.6 Cu – 2.7 |

Ge – 10.0±0.1 Te – 83.4±0.1 Cu – 2.7±0.0 |

| Ge13Te77Cu10 |

Ge – 8.3 Te – 86.1 Cu – 5.6 |

Ge – 6.6±0.1 Te – 82.2±0.1 Cu – 5.6±0.0 |

| Ge12Te73Cu15 |

Ge – 7.8 Te – 83.6 Cu – 8.6 |

Ge – 7.9±0.1 Te – 76.5±0.1 Cu – 9.7±0.0 |

| Ge11Te69Cu20 |

Ge – 7.3 Te – 81.0 Cu – 11.7 |

Ge – 0.7±0.0 Te – 71.3±0.1 Cu – 9.2±0.0 |

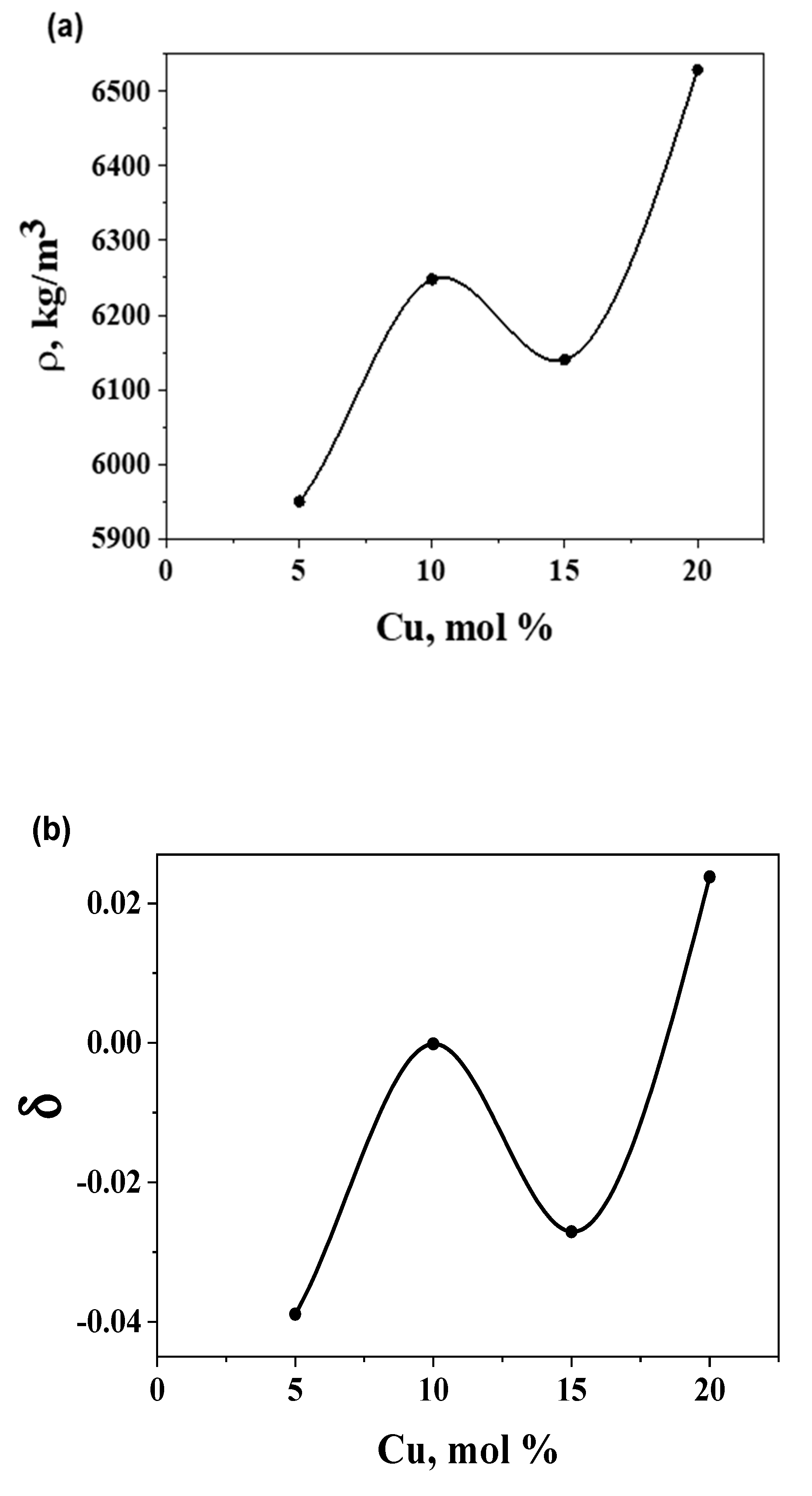

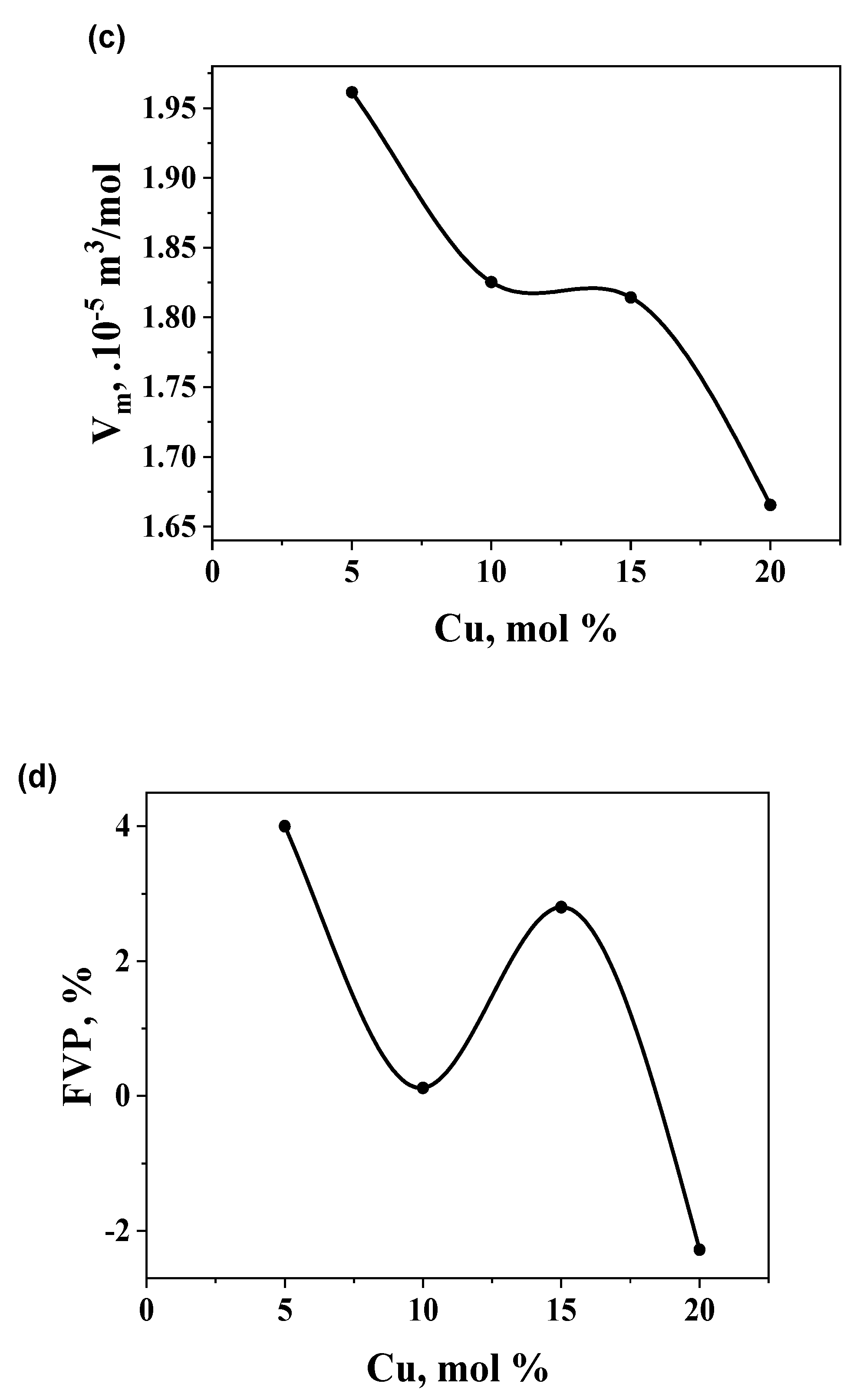

| Sample |

Density, 103 kg/m3 |

Compactness, 10-2 |

Molar volume, 10-5m3/mol |

FVP, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ge14Te81Cu5 | 5.950 | -3.890 | 1.961 | 4.00 |

| Ge13Te77Cu10 | 6.248 | -0.015 | 1.825 | 0.12 |

| Ge12Te73Cu15 | 6.140 | -2.709 | 1.814 | 2.80 |

| Ge11Te69Cu20 | 6.529 | 2.378 | 1.666 | -2.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).