1. Introduction

Botulinum toxin (BoNT) is the most potent toxin that causes botulism, a life-threatening condition characterized by flaccid paralysis. BoNT blocks neurotransmitter release by cleaving soluble

N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive-factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins at the presynaptic terminals of neurons [

1]. BoNTs are produced by

Clostridium botulinum and related species as progenitor toxin complexes (PTCs) with neurotoxin-associated proteins (NAPs) [

2]. NAPs comprise a non-toxic non-hemagglutinin (NTNHA) and three hemagglutinins (HAs: HA1, HA2, and HA3). NTNHA associates with BoNT to form M-PTC and protects the toxin from digestion and destabilization in gastrointestinal juice [

2,

3]. The HA complex is assembled from six HA1, three HA2, and three HA3 [

4,

5], and associates with medium PTC (M-PTC) to form large PTC (L-PTC), which exhibits approximately 700-fold higher oral toxicity than M-PTC [

2,

6]. HA facilitates the intestinal absorption of BoNTs through at least two activities: carbohydrate-binding [

5,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] and barrier-disrupting [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. L-PTC binds to the luminal surface of the intestinal epithelial cells via HA’s carbohydrate-binding activity [

7,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. After transcytosis from the apical to the basolateral surface, HA binds to E-cadherin and inhibits cell-cell adhesion; HA disrupts the epithelial barrier, resulting in the paracellular transport of BoNT across the intestine [

13,

15,

17].

BoNTs have been classified into seven serotypes (A-G), of which serotypes A, B, E, and F cause human botulism [

26]. L-PTCs are classified as “hyper-oral-toxic (HOT)” or “non-HOT” based on their relative oral toxicity levels [

2,

6,

25]. These classes can be categorized based on the carbohydrate-binding activity of HA [

25]. L-PTC serotype A-62A (L-PTC/A_62A), a non-hyper-oral-toxic toxin, targets intestinal microfold (M) cells for entry [

23], exerting oral toxicity by disrupting the epithelial barrier around M cells [

17,

23]. In contrast, L-PTC serotype B-Okra (L-PTC/B_Okra), which exhibits 20–80 fold greater oral toxicity and is classified as HOT-type, is taken up by enterocytes (also known as intestinal absorptive cells) [

25]. The HA of L-PTC/B_Okra increased the intestinal permeability of FITC-dextran and PTCs [

13], although the effect of the barrier-disrupting activity of L-PTC/B_Okra on oral toxicity remains unclear.

In this study, we established an in vitro reconstitution and purification system for recombinant L-PTC/B_Okra and created a recombinant L-PTC/B_Okra mutant with carbohydrate-binding activity, but not barrier-disrupting activity (rL-PTC/BB-KA). Our results demonstrate that the barrier-disrupting activity of the HOT-type toxin L-PTC/B_Okra is critically involved in its oral toxicity.

2. Results

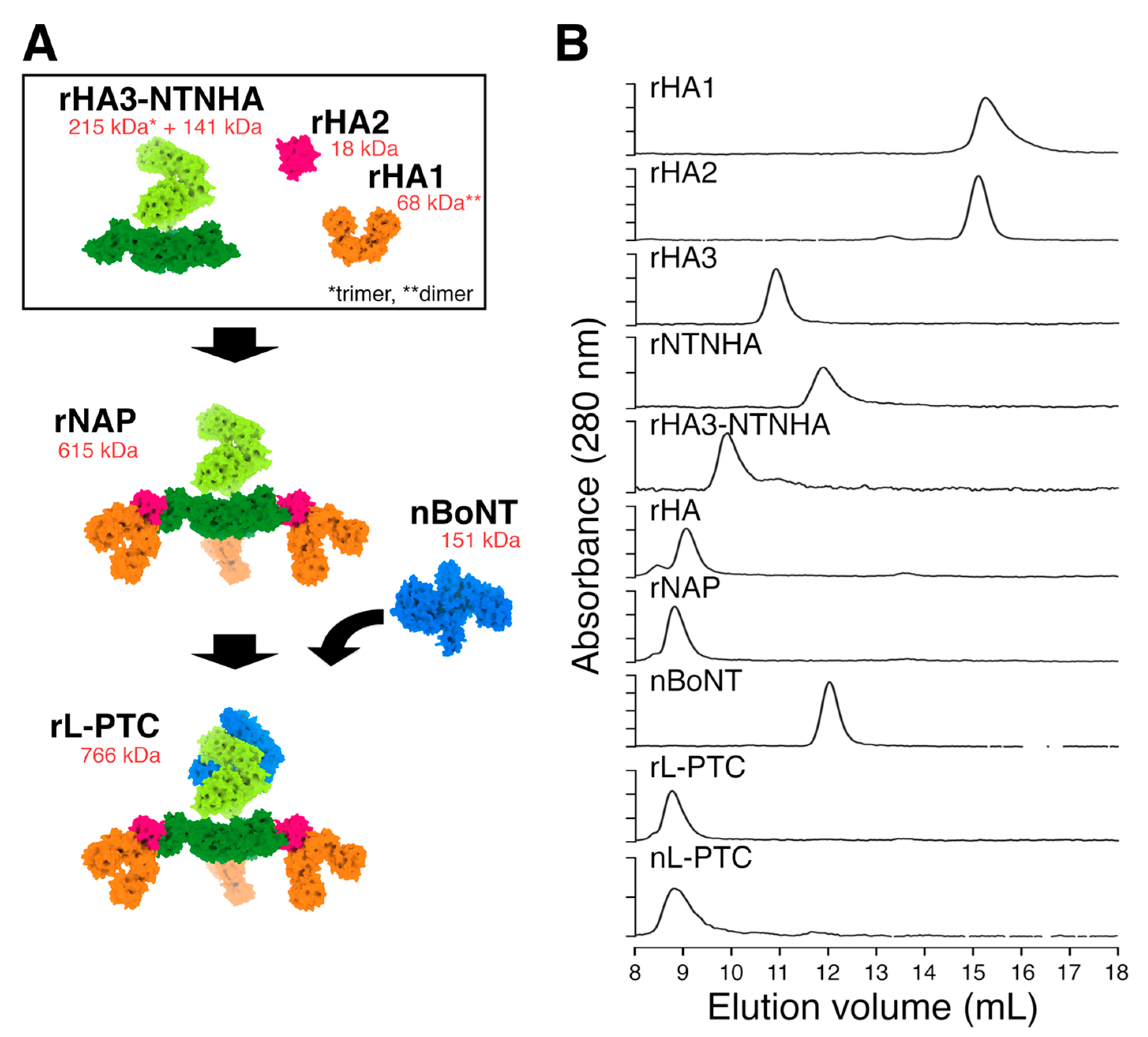

2.1. In Vitro Reconstitution and Purification of Recombinant L-PTC (rL-PTC)

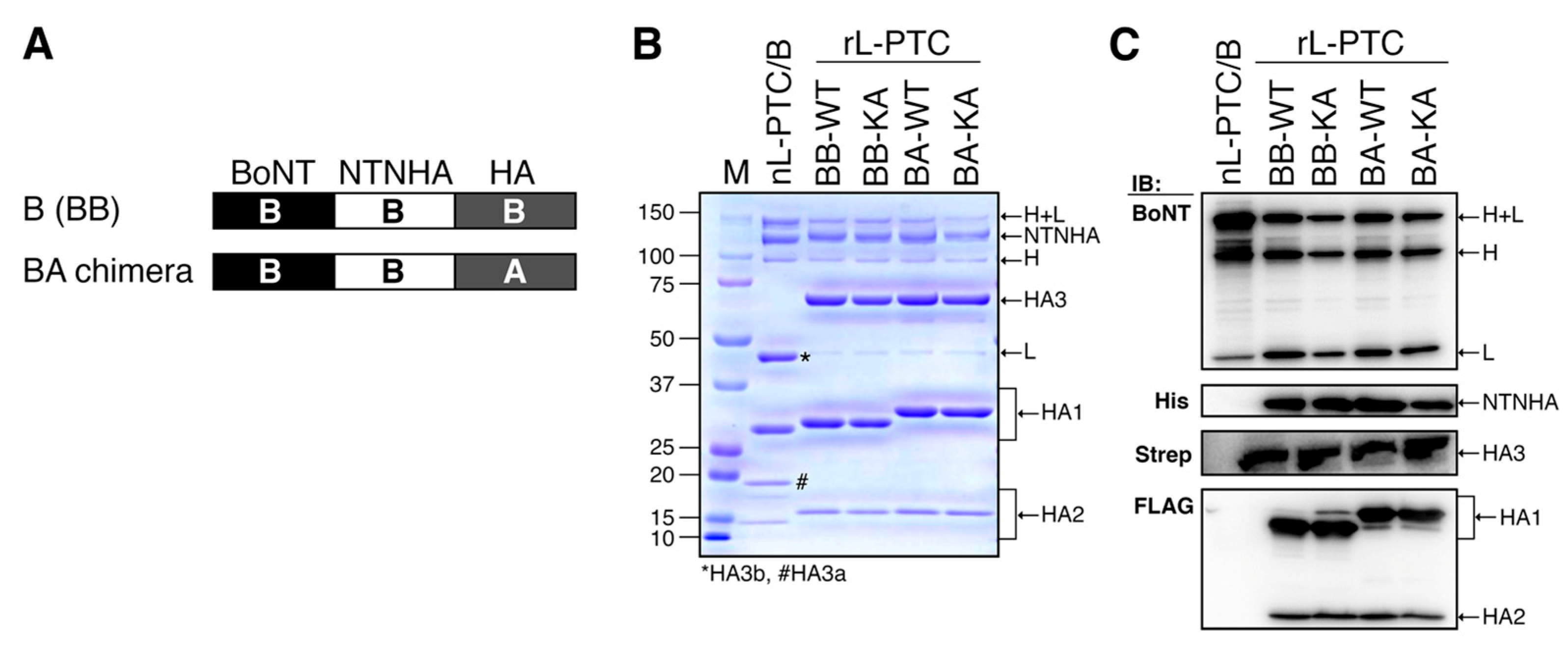

To elucidate the impact of HA differences between L-PTC/B and L-PTC/A on oral toxicity, we created rL-PTC/B (also termed rL-PTC/BB-WT) and a chimeric rL-PTC/B comprising HA/A instead of HA/B (rL-PTC/BA-WT) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2A-C) [

25]. HA3 Lys607 is crucial for the binding of HA to E-cadherin, and its alanine substitution (K607A, KA) impairs E-cadherin binding and barrier-disrupting activities [

16]. We also generated rL-PTCs containing HA3-K607A (rL-PTC/BB-KA and rL-PTC/BA-KA) (

Figure 2B,C). These rL-PTCs contained similar amounts of BoNT/B, NTNHA/B, and HAs (

Figure 2B,C).

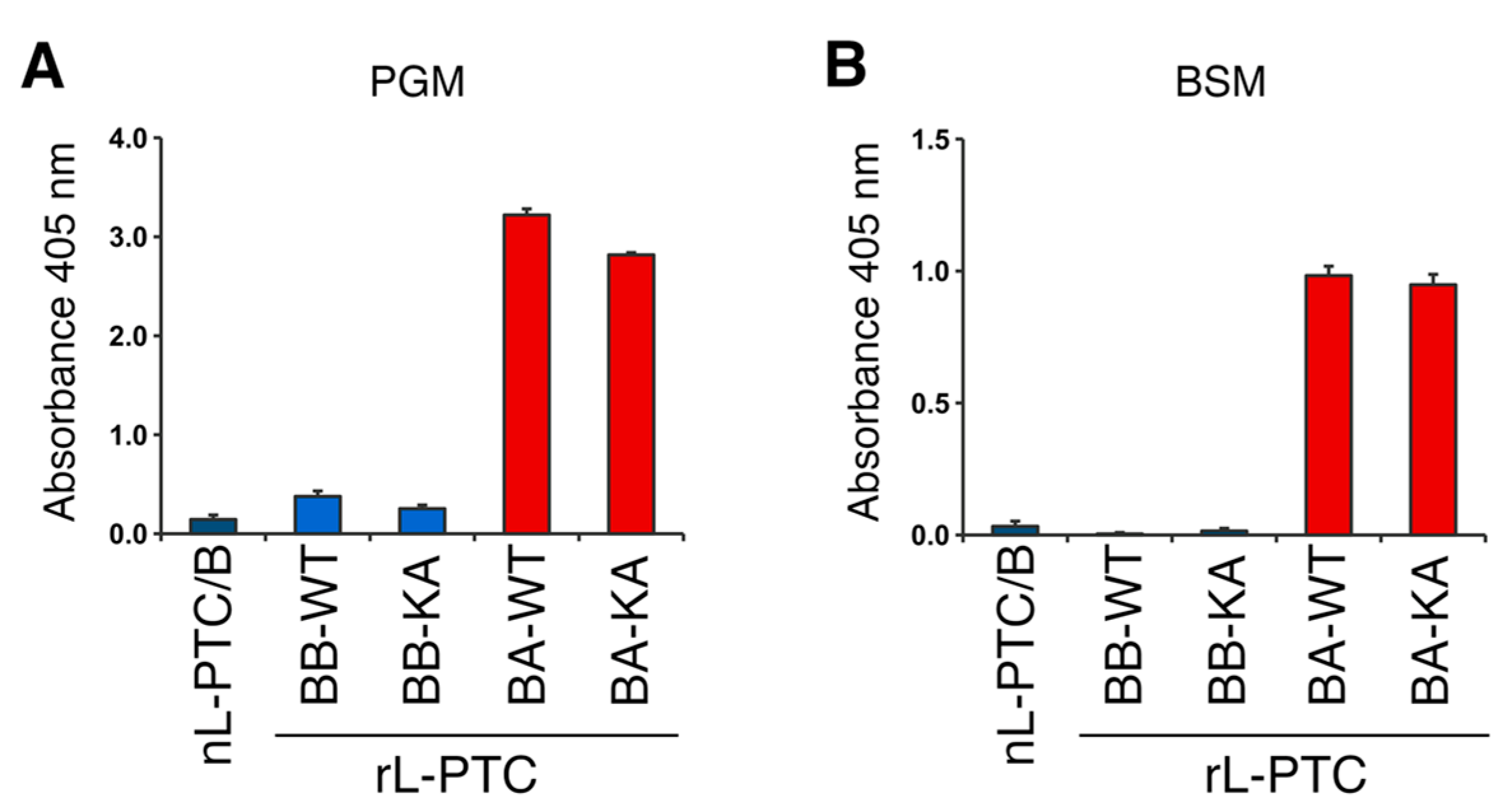

2.2. Carbohydrate-Binding Activity

L-PTC binds to the intestinal epithelium through the carbohydrate-binding activity of HA [

7,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. We assessed the carbohydrate-binding activity of rL-PTCs by ELISA using porcine gastric mucin (PGM) and bovine submaxillary mucin (BSM) [

16]. Similar to nL-PTC/B, rL-PTC/BB-WT and rL-PTC/BB-KA bound to PGM and BSM (

Figure 3). HA/A has more extended carbohydrate-binding pockets than HA/B and binds to mucins with high affinity (

Figure 3) [

25]. Similar to rL-PTC/BB, rL-PTC/BA-WT and rL-PTC/BA-KA exhibited similar binding affinities for PGM and BSM (

Figure 3). These data show that rL-PTC KA mutants have carbohydrate-binding activity comparable to that of rL-PTC-WT.

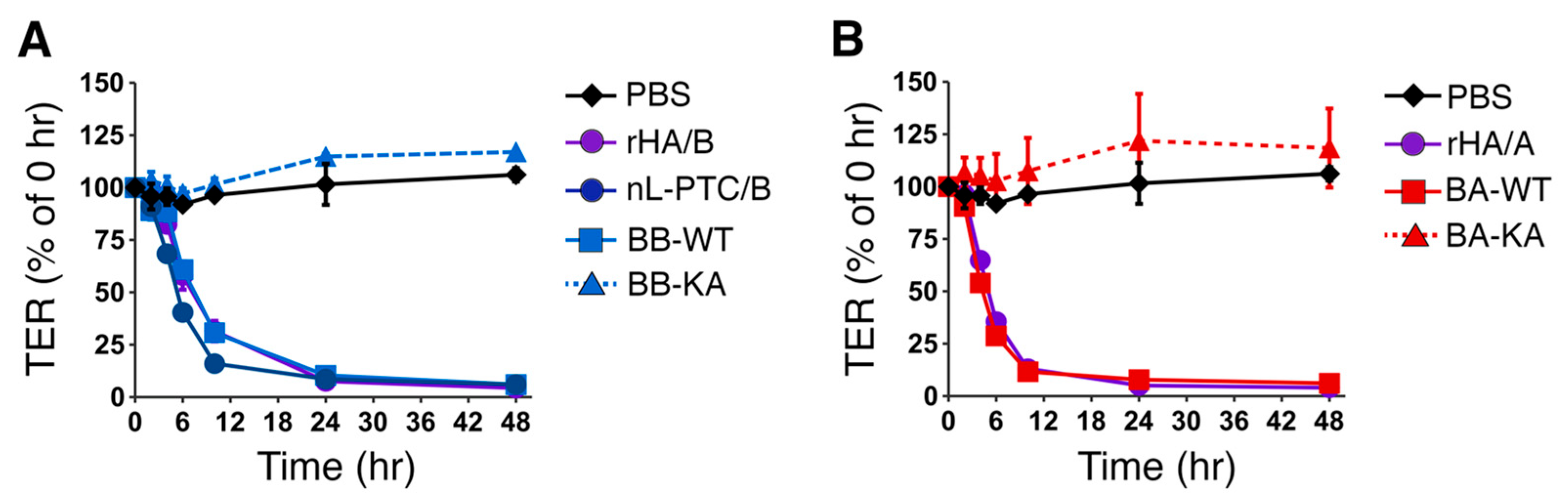

2.3. Epithelial Barrier-Disrupting Activity

HA/A and HA/B inhibit cell-cell adhesion in epithelial cells by binding to E-cadherin, resulting in epithelial barrier disruption [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. HA2 and HA3

mini (aa 380-626) are responsible for the binding of HA to E-cadherin. Notably, the recombinant HA/B (rHA/B) harboring the HA3-K607A mutant is deficient in barrier-disrupting activity [

16,

17,

18]. rL-PTC/BB-WT and rL-PTC/BA-WT disrupted the epithelial barrier of Caco-2 cell monolayers, similar to nL-PTC/B, rHA/B, and recombinant rHA/A (rHA/A) (

Figure 4). In contrast, rL-PTC/BB-KA and rL-PTC/BA-KA had no effect on the epithelial barrier function (

Figure 4). These data indicate that the HA3 K607A mutation impairs the barrier-disrupting activities of L-PTC and HA.

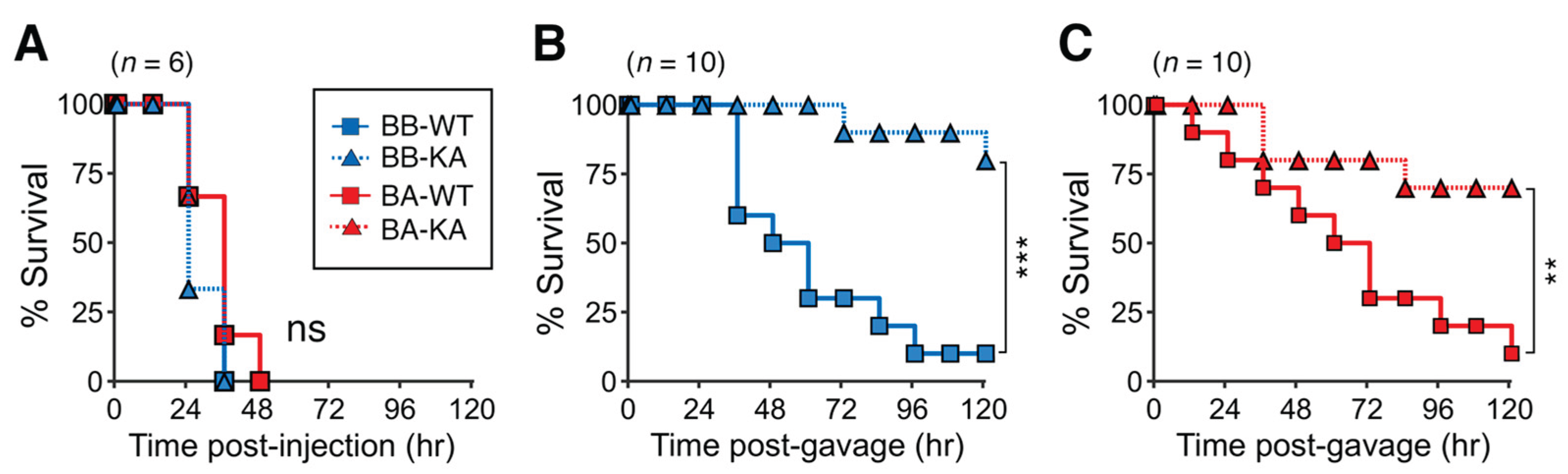

2.4. Toxicities of rL-PTC

We assessed the BoNT toxicity of rL-PTCs by intraperitoneal (i.p.) administering 200 pg of rL-PTCs to mice. L-PTCs absorbed from the intestines or injected into the bloodstream dissociate into BoNT and NAP in the circulation [

2,

3]. In other words, intraperitoneal injection resulted in the toxicity of BoNT alone in the L-PTC complex. rL-PTC/BB-WT, rL-PTC/BB-KA, rL-PTC/BA-WT, and rL-PTC/BA-KA exhibited similar BoNT toxicity (

Figure 5A). The oral toxicity of rL-PTCs was assessed by intragastrically (i.g.) administering 200 ng of rL-PTC/BBs or 2 μg rL-PTC/BAs to mice. rL-PTC/BB-WT exhibited at least a 10-fold higher oral toxicity than rL-PTC/BA-WT, indicating that the difference in HA in L-PTC affected oral toxicity (

Figure 5B,C) [

25]. rL-PTC/BB-KA, which lacks barrier-disrupting activity (

Figure 4A), exhibited dramatically reduced toxicity (

Figure 5B), similar to that of rL-PTC/BA-KA (

Figure 5C). These data demonstrate that barrier-disrupting activity is crucial for the oral toxicity of both serotypes, B-Okra and A-62A.

3. Discussion

The large botulinum toxin complex (L-PTC) comprises 14 protein subunits, including BoNT, NTNHA, HA1, HA2, and HA3, in a 1:1:6:3:3 stoichiometry [

4,

5]. Consistent with a previous study on rL-PTC/A_62A [

17], we established

an in vitro reconstitution and purification system for rL-PTC/B_Okra using nBoNT/B_Okra and its recombinant components (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The rL-PTC/BB-KA mutant exhibited carbohydrate-binding and BoNT activities comparable to those of rL-PTC/BB-WT and nL-PTC/B (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5A), but lacked barrier-disrupting activity (

Figure 4). Our findings indicate that the KA mutation impaired the oral toxicity of rL-PTC/B (

Figure 5B). These data demonstrated that barrier-disputing activity is essential for the oral toxicity of L-PTC/B_Okra.

We previously demonstrated that L-PTC/A_62A enters the host through intestinal microfold (M) cells in Peyer’s patches [

23]. Once in the intestine, the NAP of L-PTC/A_62A disrupts the epithelial barrier around M cells [

23]. Additionally, Lee

et al. [

17] reported that the absence of this barrier-disrupting activity significantly impaired the oral toxicity of rL-PTC/A_62A. The HA of L-PTC/A_62A augmented oral toxicity by compromising the barrier integrity of intestinal M cells. In contrast, we recently revealed that hyper-oral-toxic (HOT)-type toxin of serotype B-Okra, unlike non-HOT-type toxin of serotype A-62A, enters the host not only through intestinal M cells but also through the absorptive epithelial cells (enterocytes) of the small intestine [

25]. We found that L-PTC/B disrupts the epithelial barrier of enterocytes in the small intestine [

13], and the absence of this activity reduces the oral toxicity of rL-PTC/B_Okra (

Figure 5B). In summary, we demonstrated that HA of the HOT-type toxin contributes to the high oral toxicity by compromising the barrier integrity of enterocytes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plasmid Construction

Genomic DNA was extracted and purified from C. botulinum serotype B strain Okra and serotype A strain 62A. NTNHA (aa 1-1197) derived from the serotype B BoNT complex (NTNHA/B)-encoding gene, was cloned into the NheI-SalI site of the pET28b(+) vector (Merck) (pET28b-His-NTNHA/B). HA3 (aa 19-626) encoding genes derived from serotype B and A BoNT complexes (HA3/B and HA3/A, respectively) were cloned into the KpnI-SalI site of the pET52b(+) vector (Merck) (pET52b-strep-HA3/B or /A). DNA fragments encoding His-NTNHA/B and strep-HA3s were amplified by PCR and cloned into the XbaI-SacI and NdeI-XhoI sites of pETDuet(+) (Merck) using a GeneArtTM Seamless Cloning and Assembly kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the PrimeSTAR Max Polymerase (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan). The inserted regions of these plasmids and the presence of mutations were confirmed using DNA sequencing.

4.2. Protein Expression and Purification

To obtain the recombinant HA3-NTNHA (rHA3-NTNHA) complexes, Escherichia coli Rosetta2 (DE3) cells (Merck) transformed with the co-expression plasmids were grown in Terrific Broth (TB) media. Protein expression was induced using the Overnight ExpressTM Autoinduction System 1 (Merck) at 18℃ for 48 hr. The cells were then harvested and lysed in a lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 300 mM NaCl) by sonication. The His-tagged proteins were bound to HisTrap HP (Cytiva) and eluted with His elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole). To purify the HA3-NTNHA complex, the eluates were loaded onto StrepTrap HP (Cytiva) equilibrated with PBS (pH 7.4), and the bound proteins were eluted with 3 mM D-desthiobiotin.

Recombinant FLAG-tagged HA1 serotypes B and A (rHA1/B-FLAG and rHA1/A-FLAG, respectively) and recombinant FLAG-tagged HA2 serotypes B and A (FLAG-rHA2/B and FLAG-rHA2/A, respectively) were prepared as previously described [

11]. Native BoNT serotype B-Okra (nBoNT/B) was prepared as described previously [

29].

All proteins were dialyzed against PBS (pH 7.4 or 6.0) and stored at -80℃ until needed. Protein concentrations of the samples were determined using a Pierce BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

4.3. In Vitro Reconstitution and Purification

Recombinant HA complexes (rHA: HA1 + HA2 + HA3) and recombinant HA1, HA2, and HA3 proteins were mixed at a molar ratio of 4:4:1 in PBS (pH 7.4). To reconstitute recombinant NAP complexes (rNAP: NTNHA + HA), recombinant HA1, HA2, and HA3-NTNHA were mixed at a molar ratio of 12:12:1 in PBS (pH 7.4). The mixtures were then incubated at 37℃ for 3 hr. The complexes were purified using StrepTrap HP and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline PBS (pH 6.0).

To reconstitute recombinant L-PTC (rL-PTC), nBoNT/B and rNAP proteins were mixed at a molar ratio of 3:1 in PBS (pH 6.0) and incubated at 37℃ for 3 hr. The rL-PTC complexes were bound to a-Lactose gels (EY laboratories) equilibrated with PBS (pH 6.0) and then eluted with 0.2 M lactose. Purified proteins were dialyzed against PBS (pH 6.0). The protein concentrations of the samples were determined using a Pierce BCA assay.

4.4. Size Exclusion Chromatography

10 μg of each protein were loaded onto Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva) equilibrated with PBS (pH 6.0) using ÄKTA pure (Cytiva).

4.5. Western Blotting

Equimolar amounts of protein were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto Immobilon-P

TM PVDF membranes (Merck). After blocking with 5% skim milk, the membranes were incubated with antibodies against BoNT/B (rabbit, anti-serum [

13]), His tag (mouse monoclonal Ab, clone OGHis, MBL), Strep-tag II tag (mouse monoclonal Ab, Cat. 71590-3, Merck), and FLAG tag (mouse monoclonal Ab, clone M2, Merck), followed by appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Subsequently, the membranes were developed using ECL Select (Cytiva) and visualized with an ImageQuant

TM LAS 4000 mini (Cytiva).

4.6. Mucin ELISA

96-well ELISA plates (IWAKI) were coated with 100 ng/mL porcine gastric mucin (PGM; M1778, Sigma) and bovine submaxillary mucin (BSM; M3895, Sigma) at 37℃ for 1 hr. After blocking with 1% BSA/PBS-T (pH 6.0), the plates were incubated with 10 nM L-PTCs or HAs at 37℃ for 1 hr. After washing with PBS-T (pH 6.0), the plates were probed with antibodies against BoNT/B or FLAG tags, followed by incubation with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Subsequently, the plates were developed using ABTS (Merck), and the absorbance at 405 nm was measured.

4.7. Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TER) Assay

TER was measured using a Millicell-ERS (Merck), as described previously [

13]. Briefly, Caco-2 cell monolayers were established on Transwell

TM filters (Corning) and 10 nM L-PTCs or HAs were added to the basolateral chambers. TER was measured at different time points up to 48 h post-addition.

4.8. Mouse Bioassay

Female BALB/c mice aged 7-8 wk were purchased from Japan SLC. The mice were fasted for 4 h before the challenge. For intraperitoneally (i.p.) administration, the mice were injected i.p. with 100 pg of rL-PTCs in 300 μL of bioassay buffer (0.1% gelatin, 10 mM NaPi, pH 6.0). For intragastric (i.g.) administration, the mice were gavaged i.g. with 200 ng of rL-PTC/BBs or 2 μg of rL-PTC/BAs in 300 μl of bioassay buffer. The mice were re-fed 1 h after the challenge, and the survival rate was assessed every 12 h over the subsequent five days. The toxins were administered in a single-blind manner, and intoxication was scored by two investigators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S. A.; investigation, C. M., S. A., and T. M.; data analysis, M. Z.; data curation, C. M. and S. A.; writing—original draft preparation, S. A.; writing—review and editing, S. A. and Y. F.; supervision, Y. F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, Grant Numbers 19K21257 and 20K16240 to S. A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Kanazawa University (AP-163708) and performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of Kanazawa University.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mayu Kitamura and Sachiyo Akagi for their technical assistance, and the members of the Fujinaga Lab for helpful discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schiavo, G.; Matteoli, M.; Montecucco, C. Neurotoxins Affecting Neuroexocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 717–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, G. Clostridium Botulinum Toxins. Pharmacol. Ther. 1982, 19, 165–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugii, S.; Ohishi, I.; Sakaguchi, G. Correlation between Oral Toxicity and in Vitro Stability of Clostridium Botulinum Type A and B Toxins of Different Molecular Sizes. Infect. Immun. 1977, 16, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatsu, S.; Sugawara, Y.; Matsumura, T.; Kitadokoro, K.; Fujinaga, Y. Crystal Structure of Clostridium Botulinum Whole Hemagglutinin Reveals a Huge Triskelion-Shaped Molecular Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 35617–35625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Gu, S.; Jin, L.; Le, T.T.N.; Cheng, L.W.; Strotmeier, J.; Kruel, A.M.; Yao, G.; Perry, K.; Rummel, A.; et al. Structure of a Bimodular Botulinum Neurotoxin Complex Provides Insights into Its Oral Toxicity. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohishi, I. Oral Toxicities of Clostridium Botulinum Type A and B Toxins from Different Strains. Infect. Immun. 1984, 43, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinaga, Y.; Inoue, K.; Watanabe, S.; Yokota, K.; Hirai, Y.; Nagamachi, E.; Oguma, K. The Haemagglutinin of Clostridium Botulinum Type C Progenitor Toxin Plays an Essential Role in Binding of Toxin to the Epithelial Cells of Guinea Pig Small Intestine, Leading to the Efficient Absorption of the Toxin. Microbiology 1997, 143, 3841–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Sobhany, M.; Transue, T.R.; Oguma, K.; Pedersen, L.C.; Negishi, M. Structural Analysis by X-Ray Crystallography and Calorimetry of a Haemagglutinin Component (HA1) of the Progenitor Toxin from Clostridium Botulinum. Microbiology 2003, 149, 3361–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lam, K.-H.; Kruel, A.M.; Perry, K.; Rummel, A.; Jin, R. High-Resolution Crystal Structure of HA33 of Botulinum Neurotoxin Type B Progenitor Toxin Complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, Y.; Iwamori, M.; Matsumura, T.; Yutani, M.; Amatsu, S.; Fujinaga, Y. Clostridium Botulinum Type C Hemagglutinin Affects the Morphology and Viability of Cultured Mammalian Cells via Binding to the Ganglioside GM3. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 3334–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatsu, S.; Matsumura, T.; Yutani, M.; Fujinaga, Y. Multivalency Effects of Hemagglutinin Component of Type B Botulinum Neurotoxin Complex on Epithelial Barrier Disruption. Microbiol. Immunol. 2018, 62, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatsu, S.; Fujinaga, Y. Botulinum Hemagglutinin: Critical Protein for Adhesion and Absorption of Neurotoxin Complex in Host Intestine. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2132, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Jin, Y.; Kabumoto, Y.; Takegahara, Y.; Oguma, K.; Lencer, W.I.; Fujinaga, Y. The HA Proteins of Botulinum Toxin Disrupt Intestinal Epithelial Intercellular Junctions to Increase Toxin Absorption. Cell. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Takegahara, Y.; Sugawara, Y.; Matsumura, T.; Fujinaga, Y. Disruption of the Epithelial Barrier by Botulinum Haemagglutinin (HA) Proteins - Differences in Cell Tropism and the Mechanism of Action between HA Proteins of Types A or B, and HA Proteins of Type C. Microbiology 2009, 155, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, Y.; Matsumura, T.; Takegahara, Y.; Jin, Y.; Tsukasaki, Y.; Takeichi, M.; Fujinaga, Y. Botulinum Hemagglutinin Disrupts the Intercellular Epithelial Barrier by Directly Binding E-Cadherin. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, Y.; Yutani, M.; Amatsu, S.; Matsumura, T.; Fujinaga, Y. Functional Dissection of the Clostridium Botulinum Type B Hemagglutinin Complex: Identification of the Carbohydrate and E-Cadherin Binding Sites. PLoS One 2014, 9, e111170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Zhong, X.; Gu, S.; Kruel, A.M.; Dorner, M.B.; Perry, K.; Rummel, A.; Dong, M.; Jin, R. Molecular Basis for Disruption of E-Cadherin Adhesion by Botulinum Neurotoxin A Complex. Science 2014, 344, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatsu, S.; Matsumura, T.; Zuka, M.; Fujinaga, Y. Molecular engineering of a minimal E-cadherin inhibitor protein derived from Clostridium botulinum hemagglutinin. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinaga, Y.; Inoue, K.; Nomura, T.; Sasaki, J.; Marvaud, J.C.; Popoff, M.R.; Kozaki, S.; Oguma, K. Identification and Characterization of Functional Subunits of Clostridium Botulinum Type A Progenitor Toxin Involved in Binding to Intestinal Microvilli and Erythrocytes. FEBS Lett. 2000, 467, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinaga, Y.; Inoue, K.; Watarai, S.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Arimitsu, H.; Lee, J.-C.; Jin, Y.; Matsumura, T.; Kabumoto, Y.; Watanabe, T.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Binding Subcomponents of Clostridium Botulinum Type C Progenitor Toxin for Intestinal Epithelial Cells and Erythrocytes. Microbiology 2004, 150, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimitsu, H.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Lee, J.-C.; Ochi, S.; Tsukamoto, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ma, S.; Tsuji, T.; Oguma, K. Molecular Properties of Each Subcomponent in Clostridium Botulinum Type B Haemagglutinin Complex. Microb. Pathog. 2008, 45, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Lee, K.; Gu, S.; Lam, K.-H.; Jin, R. Botulinum Neurotoxin A Complex Recognizes Host Carbohydrates through Its Hemagglutinin Component. Toxins 2014, 6, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura, T.; Sugawara, Y.; Yutani, M.; Amatsu, S.; Yagita, H.; Kohda, T.; Fukuoka, S.-I.; Nakamura, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Hase, K.; et al. Botulinum Toxin A Complex Exploits Intestinal M Cells to Enter the Host and Exert Neurotoxicity. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, T.I.; Stanker, L.H.; Lee, K.; Jin, R.; Cheng, L.W. Translocation of Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotype A and Associated Proteins across the Intestinal Epithelia. Cell. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatsu, S.; Matsumura, T.; Morimoto, C.; Keisham, S.; Goto, Y.; Kohda, T.; Hirabayashi, J.; Kitadokoro, K.; Katayama, T.; Kiyono, H.; Tateno, H.; Zuka, M.; Fujinaga, Y. Gut mucin fucosylation dictates the entry of botulinum toxin complexes.

- Arnon, S.S.; Schechter, R.; Inglesby, T.V.; Henderson, D.A.; Bartlett, J.G.; Ascher, M.S.; Eitzen, E.; Fine, A.D.; Hauer, J.; Layton, M.; et al. Botulinum Toxin as a Biological Weapon: Medical and Public Health Management. JAMA 2001, 285, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohishi, I.; Sugii, S.; Sakaguchi, G. Oral Toxicities of Clostridium Botulinum Toxins in Response to Molecular Size. Infect. Immun. 1977, 16, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouguchi, H.; Watanabe, T.; Sagane, Y.; Sunagawa, H.; Ohyama, T. In Vitro Reconstitution of the Clostridium Botulinum Type D Progenitor Toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 2650–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Amatsu, S.; Misaki, R.; Yutani, M.; Du, A.; Kohda, T.; Fujiyama, K.; Ikuta, K.; Fujinaga, Y. Fully Human Monoclonal Antibodies Effectively Neutralizing Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotype B. Toxins 2020, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).