Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.2.1. Chitosan Extraction from Periwinkle Shell Powder

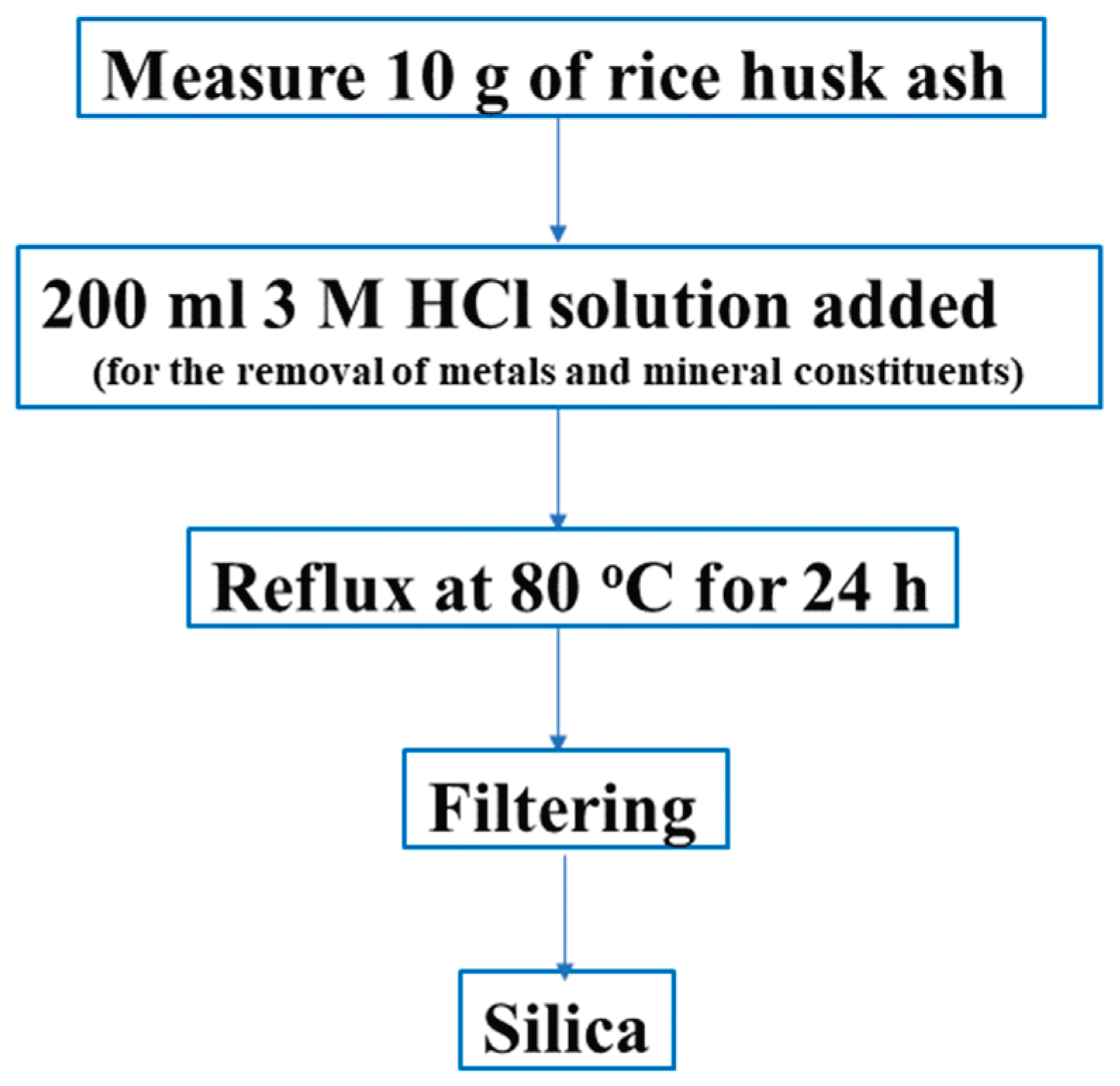

2.2.2. Silica Extraction

2.2.3. Synthesis of Porous Silica

2.2.4. Modification of Porous Silica

2.3. Characterization of the Porous Silica

2.4. Batch Adsorption Process

2.5. Adsorption Isotherms

2.6. Adsorption Kinetics

3. Results and Discussion

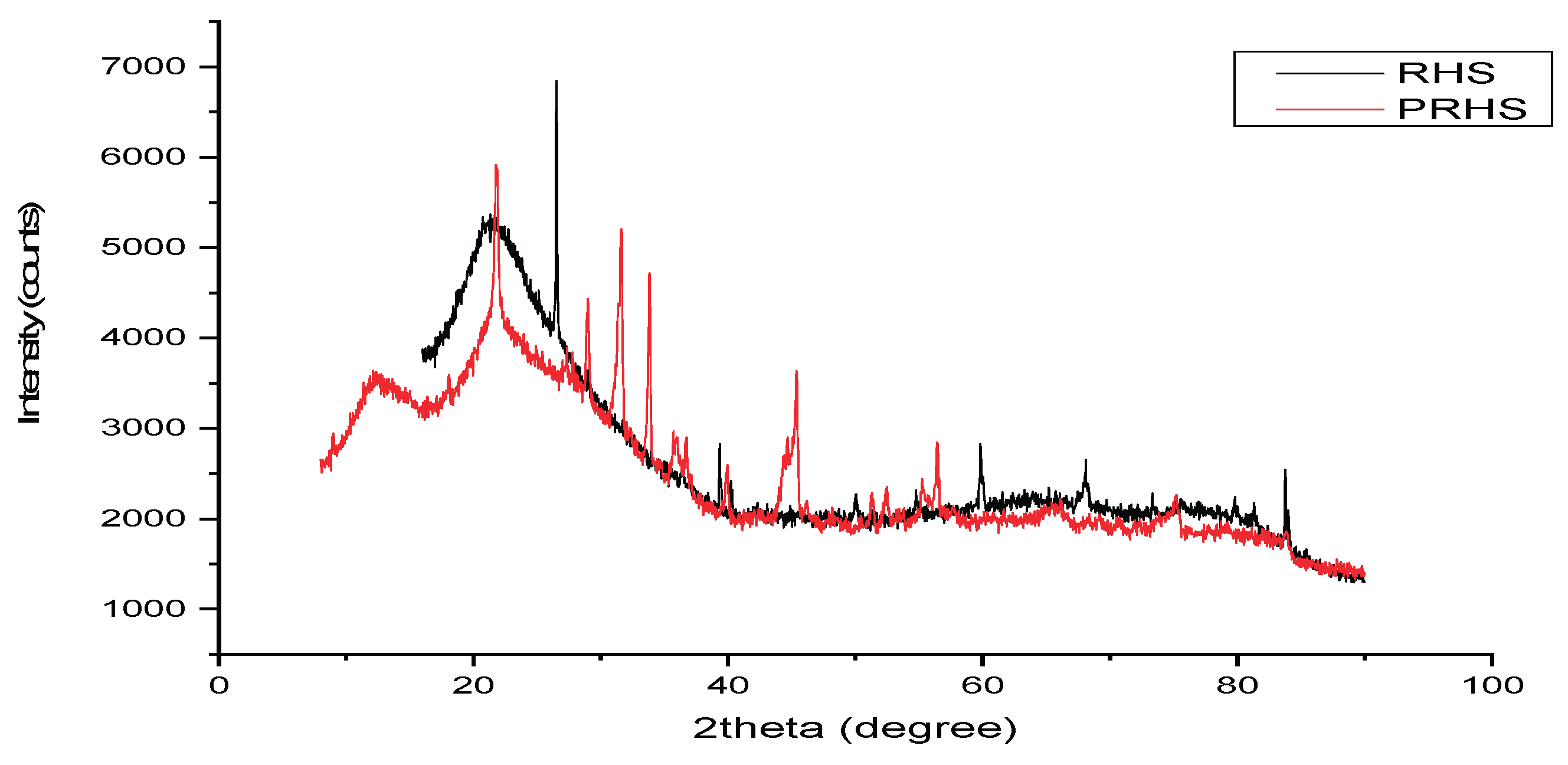

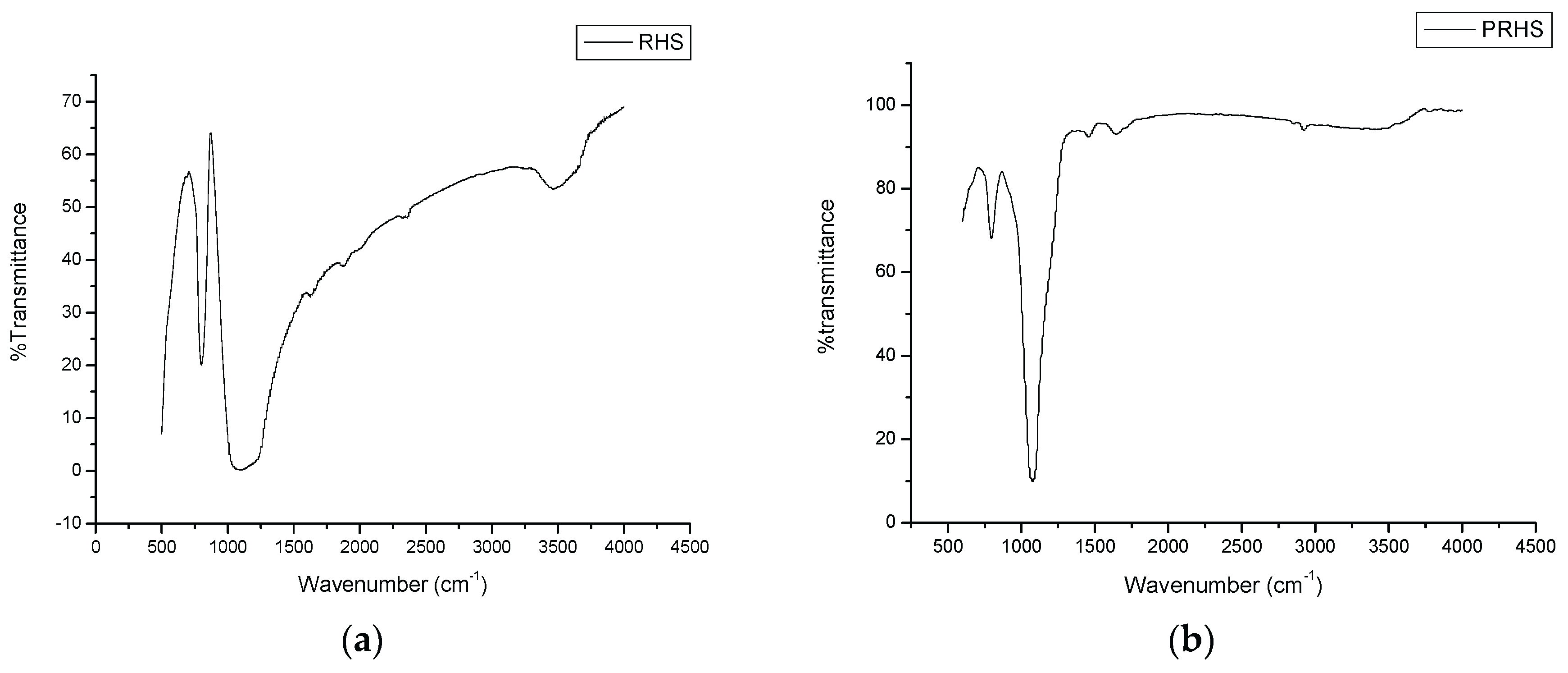

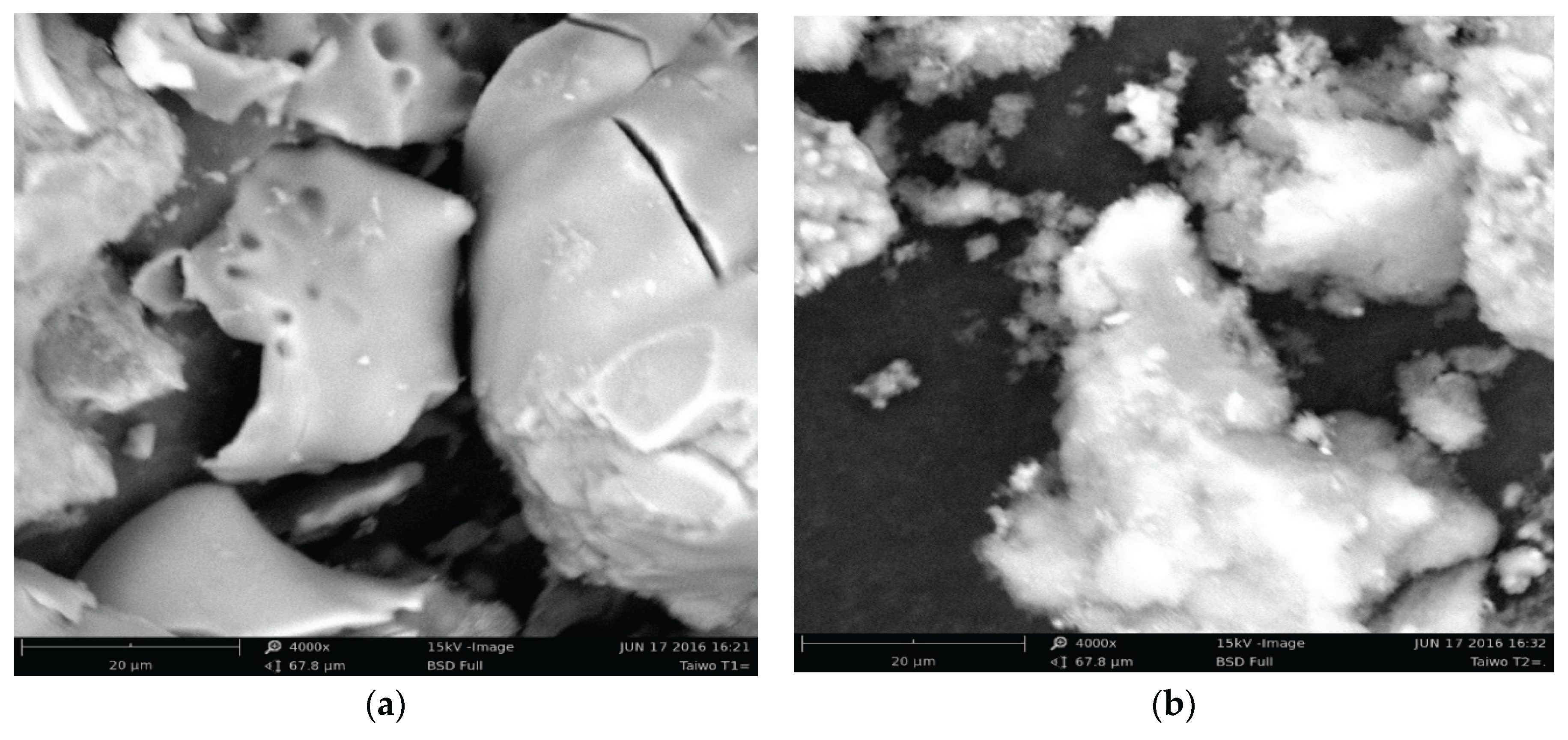

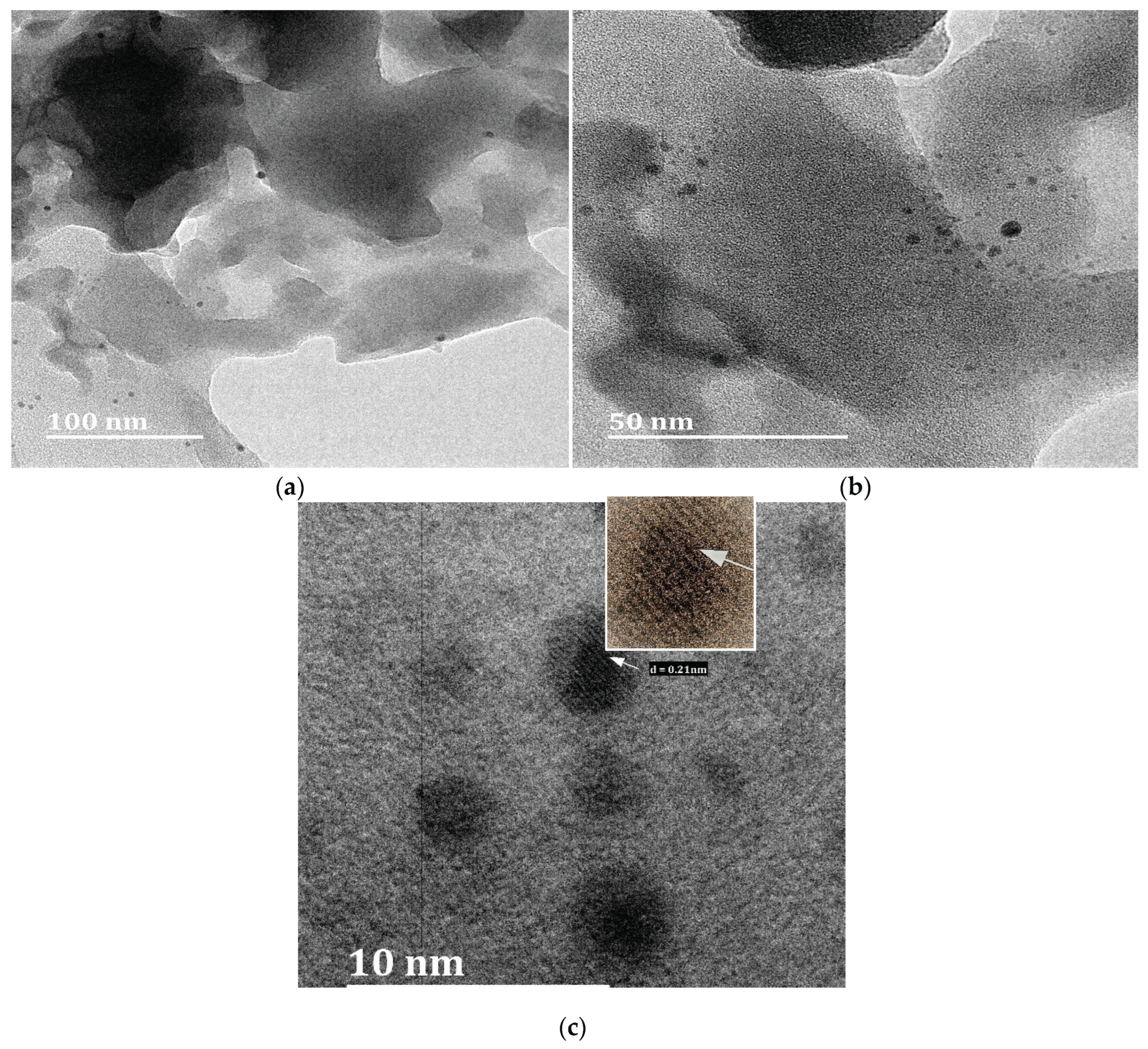

3.1. Characterisation of Silica and Porous Silica Produced from Rice Husk

3.2. Optimization Studies on the Pesticide Removal from Aqueous Solution

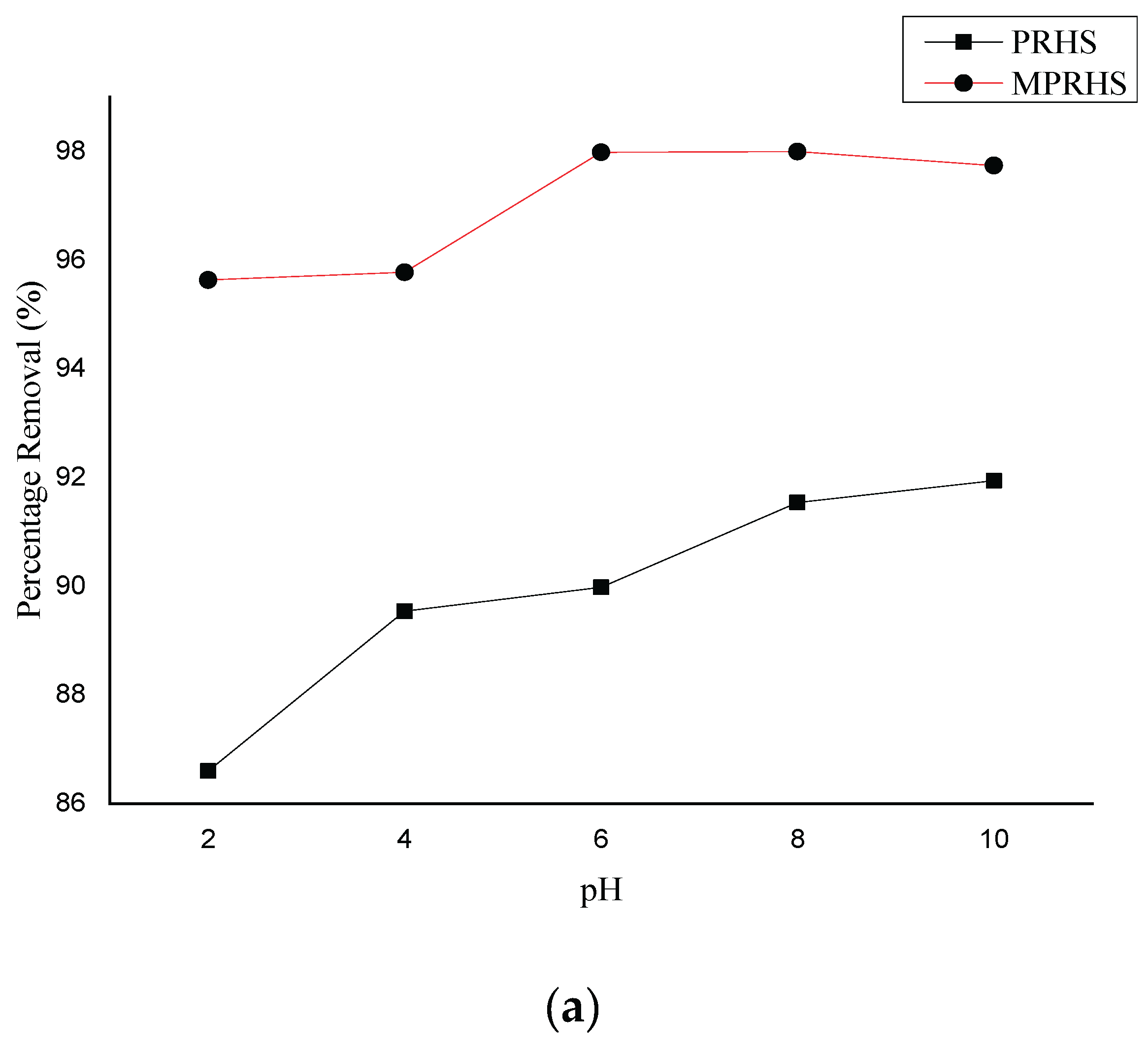

3.2.1. pH Effect on Adsorption

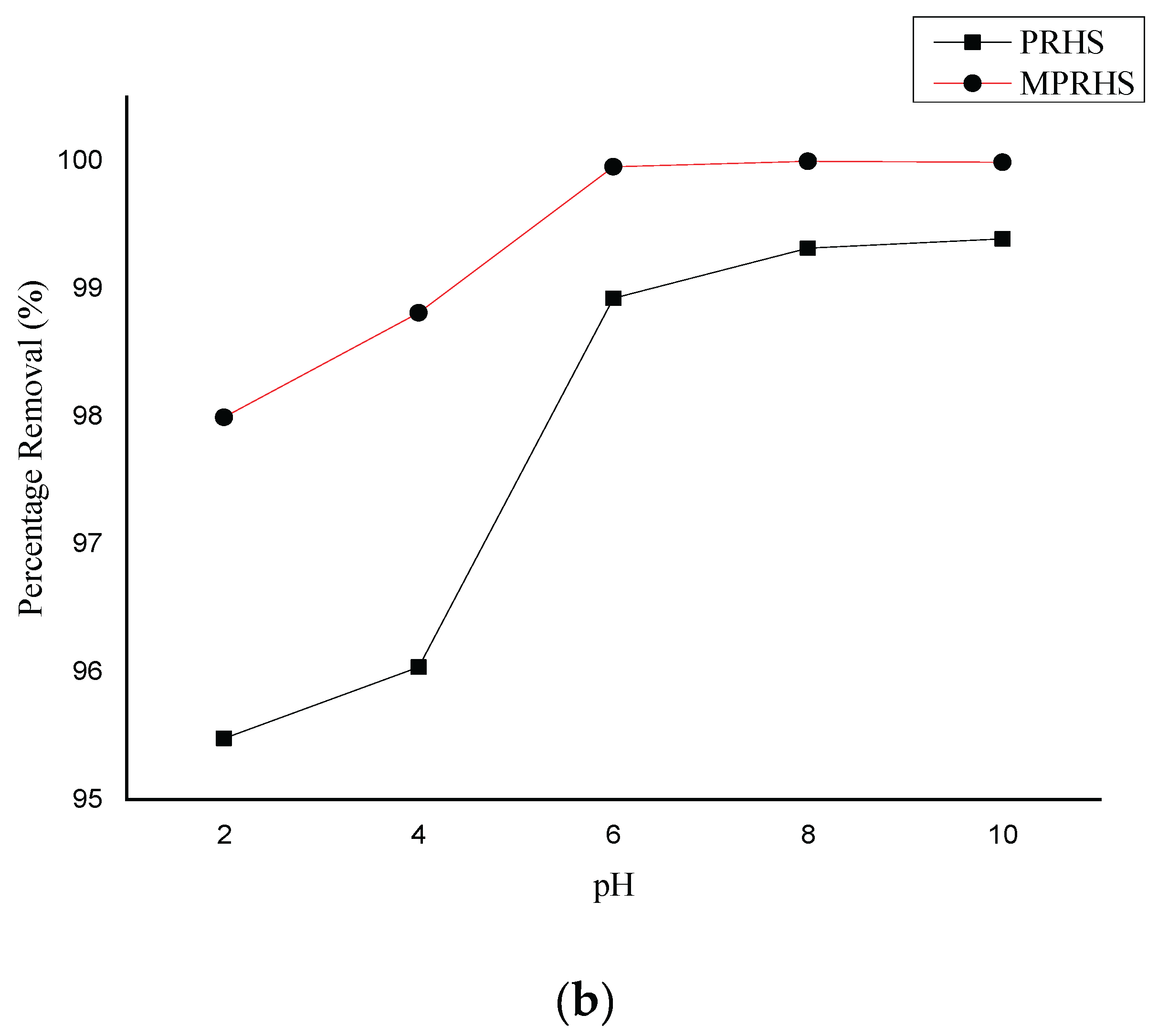

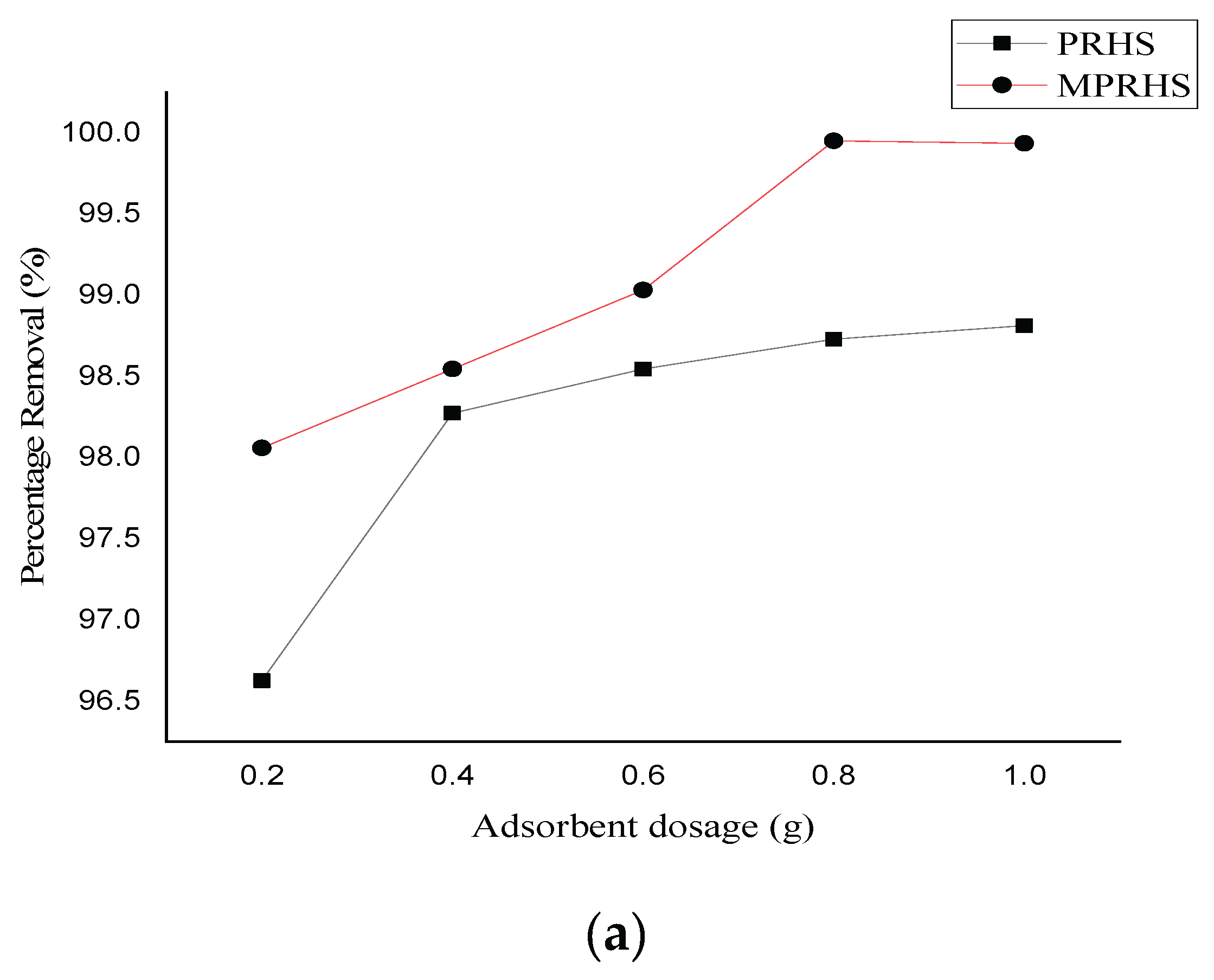

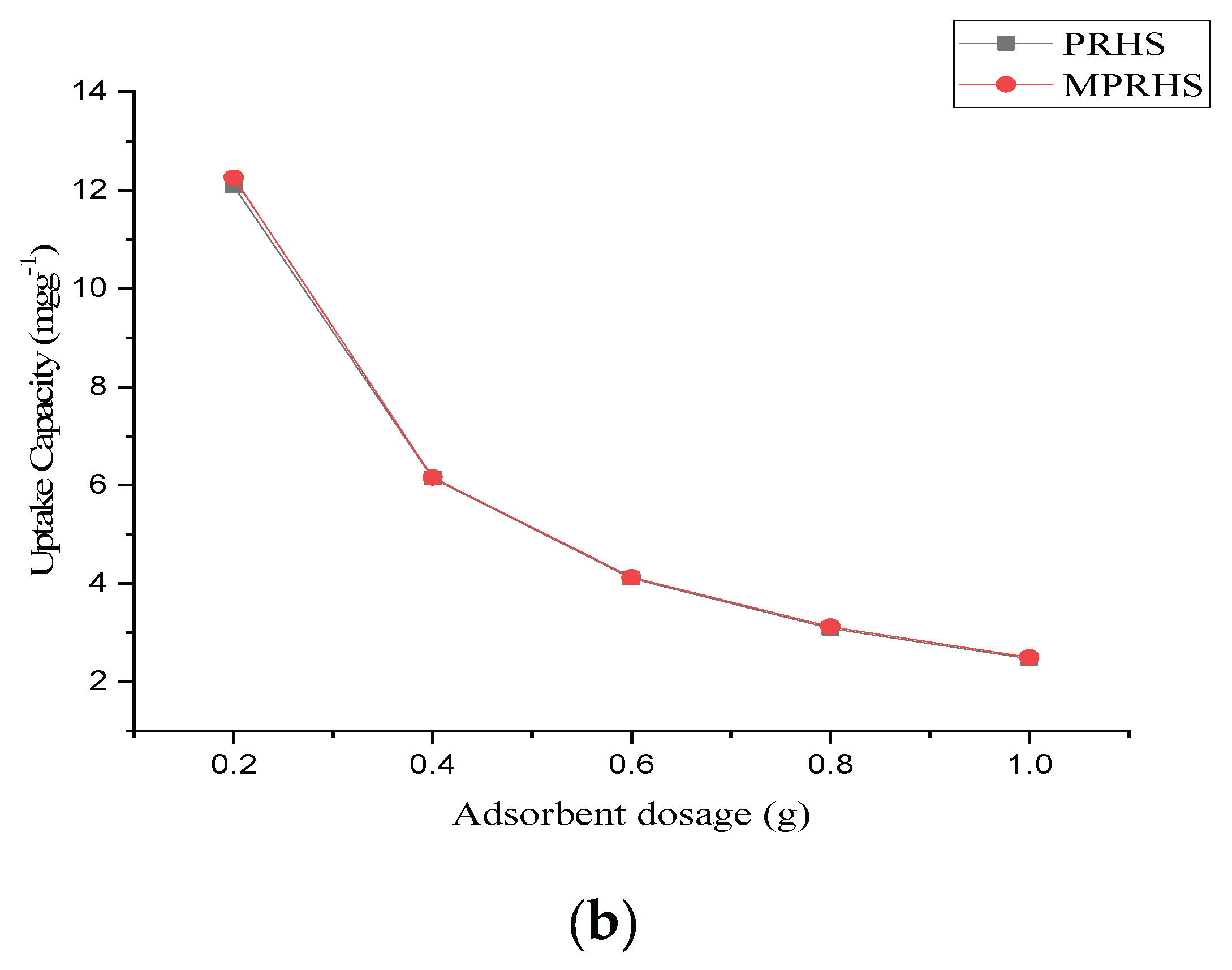

3.2.2. Adsorption Effect of Adsorbent Dosage

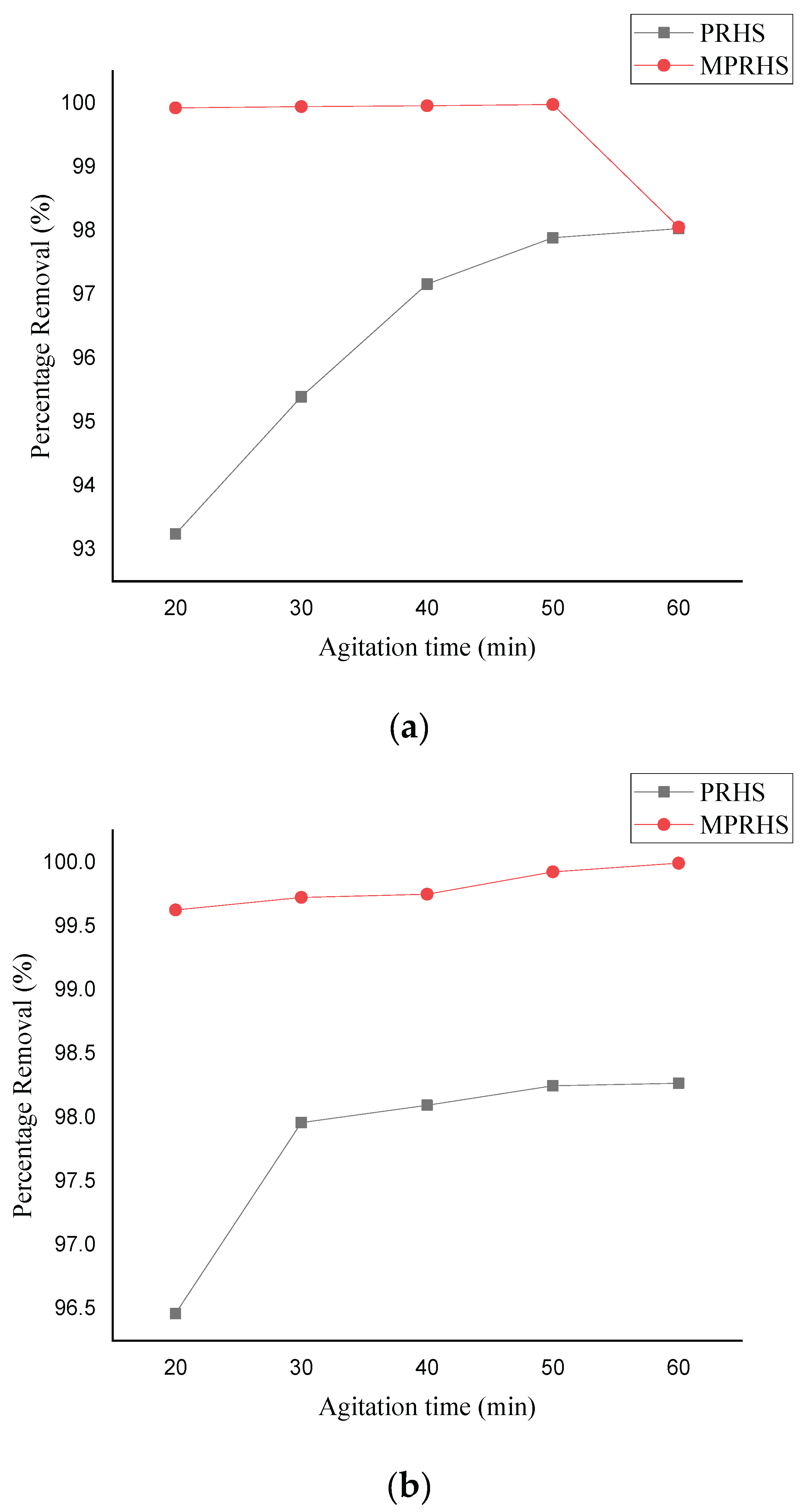

3.2.3. Effect of Agitation Time on Adsorption

3.2.4. Kinetics Studies

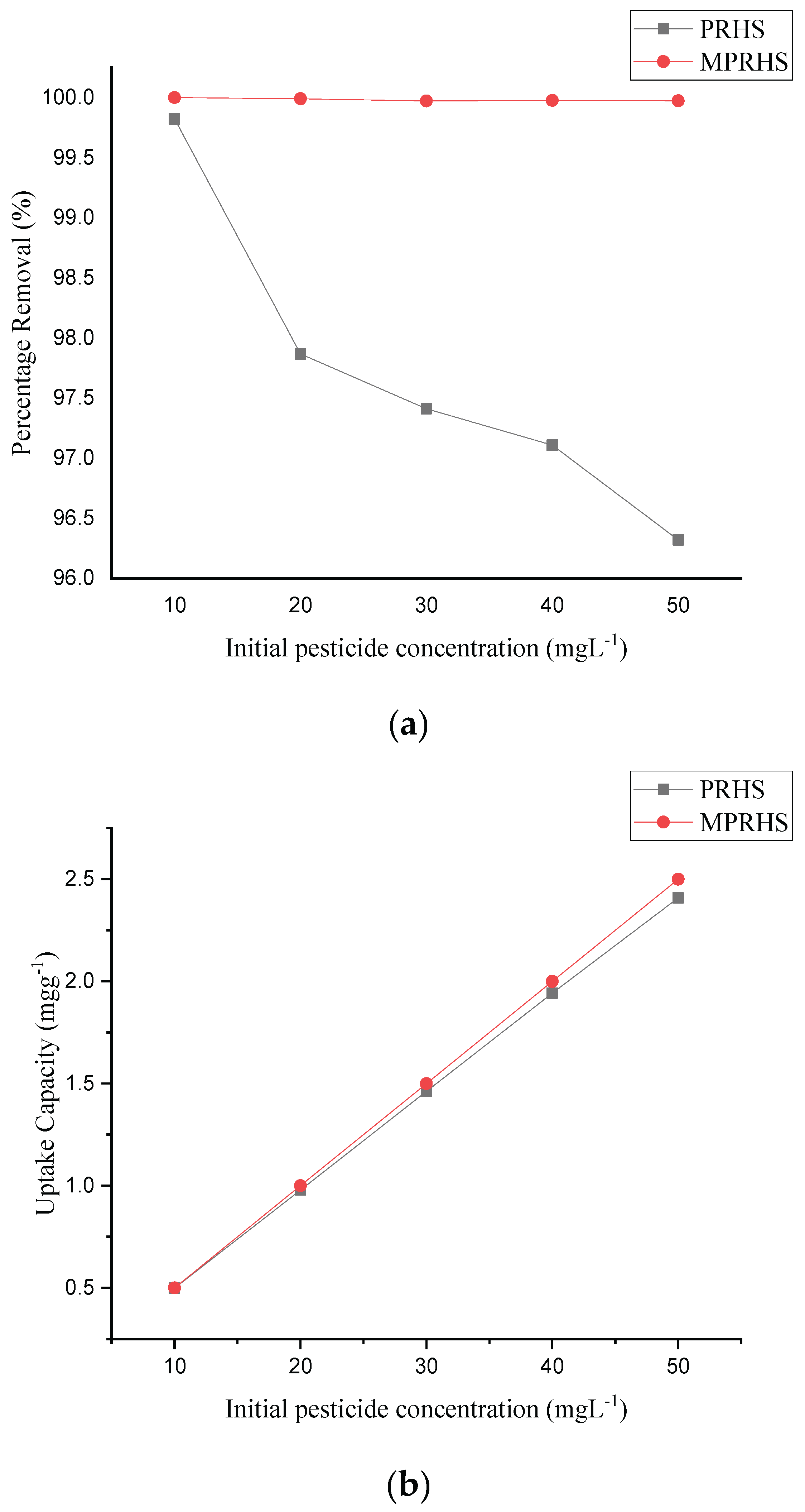

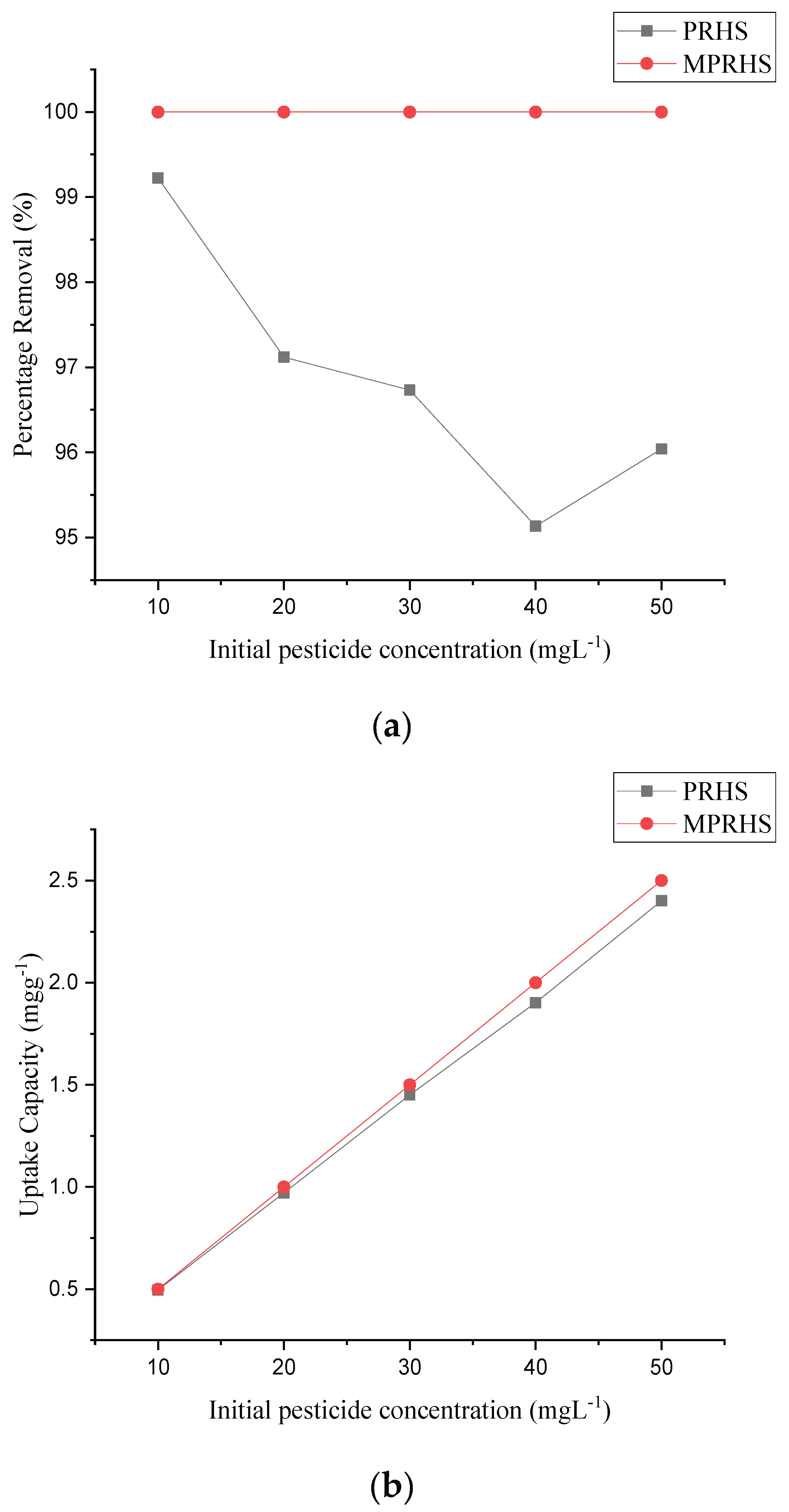

3.2.5. Effect of Pesticide Concentration on Adsorption

3.2.6. Isotherm Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Declaration of Competing Interest

Compliance with ethical standards

Acknowledgments

References

- Özkara, A.; Akyil, D.; Konuk, M. Pesticides, environmental pollution, and health. environmental health risk - hazardous factors to living species. Intech 2016. [CrossRef]

- Valdés, O.; Ávila-Salas, F.; Marican, A.; Fuentealba, N.; Villaseñor, J.; Arenas-Salinas, M.; Argandona, Y.; Durán-Lara, E.F. Methamidophos removal from aqueous solutions using a super adsorbent based on crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogel. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2017, 135(11), 45964. [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, S.; Jefferson, B.; Jarvis, P. Pesticide removal from drinking water sources by adsorption: a review. Environmental Technology Reviews 2019, 8(1), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, H.; Kapur, M.; Mondal, M.K. Comparative study of malathion removal from aqueous solution by agricultural and commercial adsorbents. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2014, 3, 67–73. [CrossRef]

- Okoya, A.A.; Sonaike, T.O.; Adekunle, O.K. Effect of application rates of selected natural pesticides on soil biochemical parameters and litter decomposition. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2014, 9(50), 3655-3662.

- Okoya, A.A.; Ogunfowokan, A.O.; Asubiojo, O.I. Torto, N. Organochlorine pesticide residues in sediments and waters from cocoa producing areas of Ondo State, Southwestern Nigeria. International Scholarly Research Notices 2013a, Volume 2013, 12 pages. [CrossRef]

- Okoya, A.A.; Torto, N.; Ogunfowokan, A.O.; Asubiojo, O.I. Organochlorine (OC) pesticide residues in soils of major cocoa plantations in Ondo State, Southwestern Nigeria. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2013b, 8(28), 3842–3848. [CrossRef]

- Erhunmwunse, N.O.; Dirisu, A.; Olomukoro, J.O. Implications of pesticide usage in Nigeria. Tropical Freshwater Biology 2012, 21(1), 15–25. [CrossRef]

- Ojo, J. Pesticides use and health in nigeria. Ife Journal of Science 2016, 18(4), 981–991.

- Szewczyk, R.; Różalska, S.; Mironenka, J.; Bernat, P. Atrazine biodegradation by mycoinsecticide Metarhizium robertsii: Insights into its amino acids and lipids profile. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 262, p.110304. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.K.; Dikshit, A.K. Atrazine and human health. Int. J. Ecosyst 2011, 1(1), 14–23.

- Hansen, S.P.; Messer, T.L.; Mittelstet, A.R. Mitigating the risk of atrazine exposure: identifying hot spots and hot times in surface waters across Nebraska, USA. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 250, 109424. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, R.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Tao, L.; Xu, W. Effects of different parameters on the removal of atrazine in a water environment by Aspergillus oryzae biosorption. Journal of Pesticide Science 2021, 46(2), 214-221.

- Bhatt, P.; Sethi, K.; Gangola, S.; Bhandari, G.; Verma, A.; Adnan, M.; Singh, Y.; Chaube, S. Modeling and simulation of atrazine biodegradation in bacteria and its effect in other living systems. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2022., 40(7), 3285–3295. [CrossRef]

- Varol, S.; Başarslan, S.K.; Fırat, U.; Alp, H.; Uzar, E.; Arıkanoğlu, A.; Evliyaoğlu, O.; Acar, A.; Yücel, Y.; Kıbrıslı, E.; Gökalp, O. Detection of borderline dosage of malathion intoxication in a rat’s brain. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci 2015,19, 2318–2323.

- Bossi, R.; Vinggaard, A.M.; Taxvig, C.; Boberg, J.; Bonefeld-Jørgensen, E.C. Levels of pesticides and their metabolites in Wistar rat amniotic fluids and maternal urine upon gestational exposure. International journal of environmental research and public health 2013, 10(6), 2271–2281. [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Meneses, M.P.; Salas-Labadía, C; Sanabrais-Jiménez, M.; Santana-Hernández, J.; Serrano-Cuevas, A.; Juárez-Velázquez, R.; Olaya-Vargas, A.; Pérez-Vera, P. Exposure to the insecticides permethrin and malathion induces leukemia and lymphoma-associated gene aberrations in vitro. Toxicology in Vitro 2017, 44, 17–26. [CrossRef]

- Okoya, A.A.; Adegbaju, O.S.; Akinyele, A.B.; Akinola, O.E.; Amuda, O.S. Comparative assessment of the efficiency of rice husk biochar and conventional water treatment method to remove chlorpyrifos from pesticide polluted water. Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology 2020, 39(2), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, R.Z.; Ma, Y.Q.; Guan, W.B.; Wu, X.L.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Du, L.Y.; Pan, C.P. Preparation of cellulose/graphene composite and its applications for triazine pesticides adsorption from water. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2015, 3(3), 396–405. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Mehta, R.; Saha, S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Biswas, P.K.; Kole, R.K. Removal of multiple pesticide residues from water by low-pressure thin-film composite membrane. Applied Water Science, 2020, 10, 1–8. 10:244. [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, T.; Bilal, M.; Nabeel, F.; Adeel, M.; Iqbal, H.M. Environmentally-related contaminants of high concern: potential sources and analytical modalities for detection, quantification and treatment. Environ Int 2018, . [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Rasheed, T.; Nabeel, F.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Zhao, Y. Hazardous contaminants in the environment and their laccase-assisted degradation – A review. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 234, 253–264. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Saha, S.; Ghosh, S.; Purkait, A.; Biswas, P.K.; Kole, R.K. Removal of pesticide residues by mesoporous alumina from water. International Journal of Chemical Studies 2019, 7(3), 1719–1725.

- KPMG. Rice industry review https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/ng/pdf/ audit/rice-industry-review.pdf 2019, (Accessed 7/13/2021).

- Chieng, S.; Kuan, S. H. Harnessing bioenergy and high value–added products from rice residues: a review. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2022, 12(8), 35473571. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, Y. Recent progress in the conversion of biomass wastes into functional materials for value-added applications. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials 2020, 21(1), 787–804. [CrossRef]

- Rudovica, V.; Rotter, A.; Gaudêncio, S.P.; Novoveská, L.; Akgül, F.; Akslen-Hoel, L.K.; Alexandrino, D.A.; Anne, O.; Arbidans, L.; Atanassova, M.; Burlakovs, J. Valorization of marine waste: use of industrial by-products and beach wrack towards the production of high added-value products. Frontiers in marine science 2021, 8, 723333. [CrossRef]

- Buzea, C.; Pacheco, I.; Robbie, K. Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: sources and toxicity. Biointerphases 2007, 2, MR17–MR71. [CrossRef]

- Jassal, V.; Shanker, U.; Kaith, B.S. Aeglemarmelos mediated green synthesis of different nano-structured metal hexacyanoferrates: Activity against photodegradation of harmful organic dyes. Scientifica 2016, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Shanker, U.; Jassal, V. Recent strategies for removal and degradation of persistent & toxic organochlorine pesticides using nanoparticles: A review. Journal of Environmental Management 2017, 190, 208–222. [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, Z.; Mohammad. S.G. Study of the adsorption efficiency of an eco-friendly carbohydrate polymer for contaminated aqueous solution by organophosphorus pesticide. Open Journal of Organic Polymer Materials 2014., 4, 16–28 DOI:10.4236/ojopm.2014.41004.

- Okoya, A.A.; Akinyele, A.B.; Amuda, O.S.; Ofoezie, I.E. Chitosan-grafted carbon for the sequestration of heavy metals in aqueous solution. American Chemical Science Journal. 2016, 11(3), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Dare, E.O.; Bello, A.O. Extraction of nanosilica from bagasse ash. unpublished undergraduate project, 2009, university of agriculture, abeokuta.

- Shaikh, I.R.; Shaikh, A.A. Utilization of wheat husk ash as silica source for the synthesis of MCM-41 type mesoporous silicates: A sustainable approach towards valorisation of the agricultural waste stream. Research Journal of Chemical Sciences 2013, 3(11), 66–72.

- Ghorbani, F.; Younesi, H.; Mehraban, Z.; Mehmet, S.C.; Ghoreyshi, A.A.; Anbia, M. Preparation and characterization of highly pure silica from sedge as agricultural waste and its utilization in the synthesis of mesoporous silica MCM-41. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2013, 44, 821–828. [CrossRef]

- Bhagiyalakshmi, M.; Yun, L.J.; Anuradha, R.; Jang, H.T. Utilization of rice husk ash as silica source for the synthesis of mesoporous silicas and their application to CO2 adsorption through TREN/TEPA grafting. Journal of Hazard Materials. 2010, 175, 928–38. [CrossRef]

- Kecili, R.; Hussain, C.M. Mechanism of adsorption on nanomaterials. Nanomaterials in Chromatography. 2018, 89–115. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-812792-6.00004-2.

- Okoronkwo, E.A.; Imoisili, P.E.; Olubayode, S.A.; Olusunle, S.O.O. Development of silica nanoparticle from corn cob ash. Advances in Nanoparticles 2016, 5, 135–139. 10.4236/anp.2016.52015.

- Saceda, J.F.; de Leon, R.L. Properties of silica from rice husk and rice husk ash and their utilization for zeolite Y synthesis. Quim. Nova 2011, 34(8), 1394–1397. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tan, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, B.; Wei, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tan, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, B.; Wei, Y.; Sun, Z.; Gao, L.; Zhong, L.; Dong, Q.; Zang, H. Research on the secondary structure and hydration water around human serum albumin induced by ethanol with infrared and near-infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Molecular Structure 2023, 1275, 134684.

- Li, N.; Guo, Q.; Wang, Q.; Liao, L. Water characterization and structural attribution of different colored opals. RSC advances 2022, 12(47), 30416–30425. [CrossRef]

- Malfait, B.; Moréac, A.; Jani, A.; Lefort, R.; Huber, P.; Fröba, M.; Morineau, D. Structure of water at hydrophilic and hydrophobic interfaces: Raman spectroscopy of water confined in periodic mesoporous (organo) silicas. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2022, 126(7), 3520-3531 . [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, R.; Mohammadi, R.; Peighambardoust, S.J.; Jalali, S.; Ramavandi, B. Application of nano-silica particles generated from offshore white sandstone for cadmium ions elimination from aqueous media. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2020, 19, 101031–. [CrossRef]

- Kamble, M.; Salvi, H.; Yadav, G.D. Preparation of amino-functionalized silica supports for immobilization of epoxide hydrolase and cutinase: characterization and applications. Journal of Porous Materials 2020. [CrossRef]

- Imoisili, P.E.; Ukoba, K.O.; Tien-Chien, J. Synthesis and characterization of amorphous mesoporous silica from palm kernel shell ash. boletín de la sociedad española de cerámica y vidrio 2020a, 59, 159–164. [CrossRef]

- Imoisili, P.E.; Ukoba, K.O.; Tien-Chien, J. Green technology extraction and characterisation of silica nanoparticles from palm kernel shell ash via sol–gel. J Mater Res Technol 2020b, 9(1), 307–313. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wu, Z.; Du, C.; Wu, Z.; Ye, B.; Cravotto, G. Enhanced adsorption of atrazine on a coal-based activated carbon modified with sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate under microwave heating. Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2017, 77, 257–262. [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.A.; Bhatti, H.N.; Hussain, I.; Bhatti, I.A.; Asghar, M. Sol–Gel Synthesis of mesoporous silica–iron composite: Kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics studies for the adsorption of Turquoise-Blue X-GB Dye. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 2019. [CrossRef]

- Alsherbeny, S.; Jamil, T.S.; El-Sawi, S.A.; Eissa, F.I. Low-cost corn cob biochar for pesticides removal from water. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 2022., 65(2), .639–650. [CrossRef]

- Gurmessa, B. K.; Taddesse, A.M.; Teju, E. UiO-66 (Zr-MOF): Synthesis, characterization, and application for the removal of malathion and 2, 4-d from aqueous solution. Environmental Pollutants and Bioavailability 2023, 35(1), p2222910. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ma, X.L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.J.; Feng, J. The adsorption behavior of atrazine in common soils in northeast China. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2019, 103, 316–322.

- Rissouli, L., Benicha, M., Chafik, T., Chabbi, M., Decontamination of water polluted with pesticide using biopolymers: Adsorption of glyphosate by chitin and chitosan. J Mater Environ Sci 2017, 8(12), 4544-4549.

- Hamadi, N.K.; Swaminathan, S.; Chen, X.D. Adsorption of paraquat dichloride from aqueous solution by activated carbon derived from used tires. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2004, 122:133–141. [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumaar, S.; Krishna, S.K.; Kalaamani, P.; Subburamaan, C.V.; Ganapathi, N. Adsorption of organophosphorous pesticide from aqueous solution using “waste” jute fiber carbon. Modern Applied Science 2010., 4(6), 67–83.

- Nor, A.B.; Hanisah, M.N.; Mohd, Y.I.; Noorain, M.I.; Mohd, A.H.; Ahmad, Z.A. Highly efficient removal of diazinon pesticide from aqueous solutions by using coconut shell-modified biochar, Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2020, 13(7), 6106–6121, . [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, S.; Bhatti, H.N., Iqbal, M., Noreen, S. Mango stone biocomposite preparation and application for crystal violet adsorption: a mechanistic study. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2017, 239, 180–189. [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaq, F.; Bhatti, H.N.; Khan, A.; Iqbal, M.; Kausar, A. Polypyrole, polyaniline and sodium alginate biocomposites and adsorption-desorption efficiency for imidacloprid insecticide. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 147, 217–232. [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Bhatti, H.N.; Iqbal, M.; Noreen, S. Eriobotrya japonica seed biocomposite efficiency for copper adsorption: Isotherms, kinetics, thermodynamic and desorption studies. Journal of Environmental Management 2016, 176, 21–33. [CrossRef]

- Sellaoui, L.; Gómez-Avilés, A.; Dhaouadi, F.; Bedia, J.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Rtimi, S.; Belver, C. Adsorption of emerging pollutants on lignin-based activated carbon: Analysis of adsorption mechanism via characterization, kinetics and equilibrium studies. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 452, 139399. [CrossRef]

- Elwakeel, K.Z.; Yousif, A.M. Adsorption of malathion on thermally treated egg shell material. Water science and Technology 2010, 1035–1041. [CrossRef]

- Okoya, A.A.; Diisu, D. Adsorption of indigo-dye from textile wastewater onto activated carbon prepared from sawdust and periwinkle shell. Trends Applied Sci. Res 2021, 16, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Alrefaee, S. H.; Aljohani, M.; Alkhamis, K.; Shaaban, F.; El-Desouky, M. G.; El-Bindary, A. A.; El-Bindary, M. A. Adsorption and effective removal of organophosphorus pesticides from aqueous solution via novel metal-organic framework: Adsorption isotherms, kinetics, and optimization via Box-Behnken design. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 384, 122206.

- Hassan, A.A.; Sajid, M.; Tanimu, A.; Abdulazeez, I.; Alhooshani, K. Removal of methylene blue and rose bengal dyes from aqueous solutions using 1-naphthylammonium tetrachloroferrate (III), Journal of Molecular Liquids 2021, 322, 114966, . [CrossRef]

- Naushad, M.; ALOthman, Z.A.; Khan, M.R.; ALQahtani, N.J.; ALSohaimi, I.H. Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamic studies for the removal of organophosphorus pesticide using Amberlyst-15 resin: Quantitative analysis by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2014. [CrossRef]

- Jusoh, A.; Hartini, W.J.H.; Ali, N.; Endut, A. Study on the removal of pesticide in agricultural run off by granular activated carbon. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102, 5312 – 5318.

- Azarkan, S.; Peña, A.; Draoui, K.; Sainz-Diaz, C.I. X Adsorption of two fungicides on natural clays of Morocco. Appl Clay Sci 2011, 123, 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Salvestrini, S.; Sagliano, P.; Iovino, P.; Capasso, S.; Colella, C. Atrazine adsorption by acid-activated zeolite-rich tuffs. Appl Clay Sci 2010, 49, 330–5. [CrossRef]

- Salmani, M.H.; Ehrampoush, M.H.; Eslami, H.; Eftekhar, B. Synthesis, characterization and application of mesoporous silica in removal of cobalt ions from contaminated water. Groundwater for sustainable development 2020, 11, 100425. [CrossRef]

- Naushad, M.; ALOthman, Z.A.; Khan, M.R. Removal of malathion from aqueous solution using De-Acidite FF-IP resin and determination by UPLC–MS/MS: Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics studies. Talanta 2013, 115, 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, W. Magnetic mesoporous imprinted adsorbent based on Fe3O4-modified sepiolite for organic micropollutant removal from aqueous solution. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 27034–42. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yin, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, C. Preponderant adsorption for chlorpyrifos over atrazine by wheat straw-derived biochar: experimental and theoretical studies. RSC Adv 2016, 6, 10615–24. [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, G.; Tamilarasan, R.; Dharmendirakumar, M. Adsorption, kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies on the removal of basic dye Rhodamine-B from aqueous solution by the use of natural adsorbent perlite. J. Mater. Environ. Sci 2012, 3(1), 157-170.

- Kumar, P.S.; Ramakrishnan, K.; Kirupha, S.D.; Sivanesan, S. Thermodynamic and kinetic studies of cadmium adsorption from aqueous solution onto rice husk, Braz J Chem Eng 2010, 27, 347–355. [CrossRef]

- Kajjumba, W.G.; Emik, S.; Öngen, A.; Özcan, K.H.; Aydın, S. Modelling of adsorption kinetic processes—errors, theory and application. Advanced Sorption Process Applications 2018. [CrossRef]

- Akpomie, K.G.; Dawodu, F.A. Efficient abstraction of nickel (II) and manganese (II) ions from solution onto an alkaline-modified montmorillonite. J Taibah Uni Sci 2014, 8, 343–56. [CrossRef]

- Akpomie, K.G;, Dawodu, F.A. Potential of a low-cost bentonite for heavy metal abstraction from binary component system. Beni – Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2015, 4, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Aharoni, C.; Tompkins, F.C. Kinetics of adsorption and desorption and the Elovich equation. In Advances in Catalysis and Related Subjects, Eley, D.D., Pines, H., Weisz, P.B., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, 1970, Volume 21, pp. 1–49. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T. A. Kinetic models and thermodynamics of adsorption processes: Classification. In Interface science and technology 2022, Volume 34, pp. 65–97. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, R.S.; Tiwari, P.N.; Singh, J.K.; Gode, F.; Sharma, Y.C. Removal of malathion from aqueous solutions and waste water using fly ash. J Water Resource and Protection 2010, 2, 322–330. DOI:10.4236/jwarp.2010.24037.

- Agarwal, S.; Tyagi, I.; Gupta, V.K.; Fakhri, A.; Sadeghi, N. Adsorption of toxic carbamate pesticide oxamyl from liquid phase by newly synthesized and characterized graphene quantum dots nanomaterials. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bruzzoniti, M.C.; De Carlo, R.M.; Rivoira, L.; Del Bubba, M.; Pavani, M.; Riatti, M.; Onida, B. Adsorption of bentazone herbicide onto mesoporous silica: application to environmental water purification. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2015, 1 - 11. [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, T. A.; Alene, A. N. A comparative study of acidic, basic, and reactive dyes adsorption from aqueous solution onto kaolin adsorbent: Effect of operating parameters, isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics. Emerging Contaminants 2022, 8, 59-74. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudian, M.H.; Azari, A.; Jahantigh, A.; Sarkhosh, M.; Yousefi, M.; Razavinasab, S.A.; Afsharizadeh, M.; Shahraji, F.M.; Pasandi, A.P.; Zeidabadi, A.; Bardsiri, T.I. Statistical modeling and optimization of dexamethasone adsorption from aqueous solution by Fe3O4@ NH2-MIL88B nanorods: Isotherm, kinetics, and thermodynamic. Environmental Research 2023, 236, 116773. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hossain, M.F.; Duan, C.; Lu, J.; Tsang, Y.F.; Islam, M.S.; Zhou, Y. Isotherm models for adsorption of heavy metals from water-A review. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135545.

- Yue, Y.; Adhab, A.H.; Sur, D.; Menon, S.V.; Singh, A.; Supriya, S.; Mishra, S.B.; Nathiya, D.; Mahdi, M.S.; Mansoor, A.S.; Radi, U.K.; Thermodynamic modelling adsorption behavior of a well-known gelation crosslinker on sandstone rocks. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1), 22544. [CrossRef]

- Anirudhan, T.S.; Suchithra, P.S. Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic modeling for the adsorption of heavy metals onto chemically modified hydrotalcite. Ind. J. Chem. Technol 2010, 17, 247–259.

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Lin, H.; Xu, R.; Zhu, H.; Bao, L.; Xu, X. Lanthanum carbonate grafted ZSM-5 for superior phosphate uptake: Investigation of the growth and adsorption mechanism. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 430, 133166. [CrossRef]

| Element Symbol | Element Name | Confidence | RHS | PRHS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration % | Error | Concentration % | Error | |||

| Si | Silicon | 100.0 | 23.7 | 0.9 | 18.9 | 1.2 |

| O | Oxygen | 100.0 | 76.3 | 1.5 | 73.9 | 1.6 |

| Na | Sodium | 100.0 | 6.3 | 4.2 | ||

| Br | Bromine | 100.0 | 0.9 | 4.8 | ||

| Kinetics Models | PRHS | MPRHS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrazine | Malathion | Atrazine | Malathion | |

| qeexp (mg/g) | 3.06 | 3.07 | 3.12 | 3.125 |

| Pseudo-First Order | ||||

| qecal (mg/g) | 2.027 | 0.907 | 0.098 | 26.152 |

| K1 (min-1) | 0.116 | 0.141 | 0.051 | 0.052 |

| R2 | 0.9495 | 0.9591 | 1 | 0.8011 |

| Pseudo-second Order | ||||

| K2 (g/mgmin) | 0.175 | 0.602 | 22.260 | 2.980 |

| qecal (mg/g) | 3.170 | 3.106 | 3.125 | 3.128 |

| h (mg/gmin) | 1.758 | 5.807 | 217.391 | 29.156 |

| R2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Intraparticle Diffusion | ||||

| Kd (mg/gmin1/2) | 0.0473 | 0.0157 | 0.0006 | 0.0035 |

| C | 2.7163 | 2.9589 | 3.1197 | 3.0969 |

| R2 | 0.9317 | 0.723 | 0.9921 | 0.9377 |

| Liquid film Diffusion | ||||

| Kfd | 0.1158 | 0.1409 | 0.0509 | 0.0518 |

| I | 0.4128 | 1.2192 | 6.481 | 4.4032 |

| R2 | 0.9495 | 0.9591 | 1 | 0.8011 |

| Elovich equation | ||||

| α (mg/gmin) | 4.821x105 | 2.47x1019 | 3.02x10-843 | 1.6x10145 |

| β (g/min) | 6.139 | 16.694 | 635 | 109.890 |

| R2 | 0.9922 | 0.8373 | 0.9982 | 0.8606 |

| Isotherm Models | PRHS | MPRHS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrazine | Malathion | Atrazine | Malathion | |

| Langmuir | ||||

| qL | 2.434 | 2.832 | 2.782 | 0 |

| KL | 513.558 | 1.354 | 0.763 | 0 |

| R2 | 0.8533 | 0.8498 | 0.8516 | 0 |

| Freudlich | ||||

| KF | 0.650 | 1.483 | 1.691 | 0 |

| n | -5.740 | 2.195 | 3.085 | 0 |

| 1/n | -0.174 | 0.456 | 0.324 | 0 |

| R2 | 0.4135 | 0.9568 | 0.924 | 0 |

| Temkin | ||||

| B | -0.1604 | 0.864 | 0.3616 | 0 |

| A | 0.005 | 9.355 | 135.368 | 0 |

| R2 | 0.2265 | 0.809 | 0.7791 | 0 |

| Scatchard | ||||

| B | 16.374 | 2.3293 | -11.426 | 0 |

| Qm | 8.0836 | 2.453 | 12.314 | 0 |

| R2 | 0.0052 | 0.5899 | 0.5323 | 0 |

| Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) | ||||

| Β | 3x10-9 | -3x10-8 | -1x10-8 | 0 |

| qmD-R | 0.8848 | 1.764 | 1.710 | 0 |

| R2 | 0.1714 | 0.8033 | 0.7658 | 0 |

| E KJ/mol | 15909.95 | 4082.48 | 7071.07 | 0 |

| PRHS | MPRHS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrazine | Malathion | Atrazine | Malathion | |

| Co | RL | RL | RL | RL |

| 10 | 0.000195 | 0.068776 | 0.115875 | 1 |

| 20 | 9.74E-05 | 0.035613 | 0.061501 | 1 |

| 30 | 6.49E-05 | 0.024027 | 0.041859 | 1 |

| 40 | 4.87E-05 | 0.018129 | 0.031726 | 1 |

| 50 | 3.89E-05 | 0.014556 | 0.025543 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).