Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Interim Summary & Action Steps

5. What Constitutes the Reference Range for These Minerals?

6. Potential for Reducing Risks

7. Discussion

References

- National Institutes of Health. Calcium Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-HealthProfessional/. Accessed 8 August 2024.

- Weaver CM, Heaney RP, Eds. Calcium in Human Health. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. 2006.

- Elíes, J.; Yáñez, M.; Pereira, T.M.C.; Gil-Longo, J.; MacDougall, D.A.; Campos-Toimil, M. An Update to Calcium Binding Proteins. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020, 1131, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkwarf, HJ. Calcium in pregnancy and lactation. Chapter 18, pp. 297-309 in: Calcium in Human Health, Weaver CM, Heaney RP, Eds. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, 2006.

- Touyz, R.M.; de Baaij, J.H.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Ingelfinger, J.R. Magnesium Disorders. New Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1998–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothari, M.; Wanjari, A.; Shaikh, S.M.; Tantia, P.; Waghmare, B.V.; Parepalli, A.; Hamdulay, K.F.; Nelakuditi, M. A Comprehensive Review on Understanding Magnesium Disorders: Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management Strategies. Cureus 2024, 16, e68385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kröse, J.L.; de Baaij, J.H.F. Magnesium biology. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.A.; Panonnummal, R. ‘Magnesium’-the master cation-as a drug—possibilities and evidences. BioMetals 2021, 34, 955–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoke JE, Yanari S, Bloch K. Synthesis of glutathione from gamma-glutamylcysteine. J Biol Chem. 1953, 201, 573–586. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanari, S.; Snoke, J.E.; Bloch, K. Energy sources in glutathione synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1953, 201, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangherlin, A.; O’nEill, J.S. Signal Transduction: Magnesium Manifests as a Second Messenger. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R1403–R1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, C.S. Maternal Mineral and Bone Metabolism During Pregnancy, Lactation, and Post-Weaning Recovery. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 449–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, E.; Odonnell, A.; Nelson, S.; Fomon, S. Body-composition of reference fetus. Growth 1976, 40, 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, A.; Palm, M.; Hansson, L.; Axelsson, O. Reference values for clinical chemistry tests during normal pregnancy. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 115, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Pu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Zhang, C. Evaluation of serum electrolytes measurement through the 6-year trueness verification program in China. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020, 59, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wu, M.; Zhang, G.; Lin, L.; Tu, M.; Xiao, D.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Longitudinal plasma magnesium status during pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 65392–65400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansu, K.; Cikim, I.G. Vitamin and mineral levels during pregnancy. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 68, 1705–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Phosphorus: Fact sheet for professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Phosphorus-HealthProfessional/.

- De Jorge, F.B.; Delascio, D.; De Ulhoa Cintra, A.B.; Antunes, M.L. Magnesium concentration in the blood serum of normal pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 1965, 25, 253–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rigo, J.; Pieltain, C.; Christmann, V.; Bonsante, F.; Moltu, S.J.; Iacobelli, S.; Marret, S. Serum Magnesium Levels in Preterm Infants Are Higher Than Adult Levels: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Xu, Q.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Shi, R. High-Normal Serum Magnesium and Hypermagnesemia Are Associated With Increased 30-Day In-Hospital Mortality: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheungpasitporn, W.; Thongprayoon, C.; Chewcharat, A.; Petnak, T.; Mao, M.A.; Davis, P.W.; Bathini, T.; Vallabhajosyula, S.; Qureshi, F.; Erickson, S.B. Hospital-Acquired Dysmagnesemia and In-Hospital Mortality. Med Sci. 2020, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, I.G.; Vega, A.; Goicoechea, M.; Shabaka, A.; Gatius, S.; Abad, S.; López-Gómez, J.M. Impact of Serum Magnesium Levels on Kidney and Cardiovascular Prognosis and Mortality in CKD Patients. J. Ren. Nutr. 2021, 31, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, N.F.; Reidinger, C.J.; Robertson, A.D.; Brenner, M. Bone mineral density changes during lactation: maternal, dietary, and biochemical correlates. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 1738–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.; Fente, C.; Barreiro, R.; López-Racamonde, O.; Cepeda, A.; Regal, P. Association between Breast Milk Mineral Content and Maternal Adherence to Healthy Dietary Patterns in Spain: A Transversal Study. Foods 2020, 9, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Solomons, N.W.; E Scott, M.; Koski, K.G. Minerals and Trace Elements in Human Breast Milk Are Associated with Guatemalan Infant Anthropometric Outcomes within the First 6 Months. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2067–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, A.; Marin, T.; De Leo, G.; Waller, J.L.; Stansfield, B.K. Nutrient composition of preterm mother’s milk and factors that influence nutrient content. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridis, I.; Kasapidou, E.; Dagklis, T.; Leonida, I.; Leonida, C.; Bakaloudi, D.R.; Chourdakis, M. Nutrition in Pregnancy: A Comparative Review of Major Guidelines. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2020, 75, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.B.; Sorenson, J.C.; Pollard, E.L.; Kirby, J.K.; Audhya, T. Evidence-Based Recommendations for an Optimal Prenatal Supplement for Women in the U.S., Part Two: Minerals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciosek, Ż.; Kot, K.; Kosik-Bogacka, D.; Łanocha-Arendarczyk, N.; Rotter, I. The Effects of Calcium, Magnesium, Phosphorus, Fluoride, and Lead on Bone Tissue. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, C.S. The Skeleton Is a Storehouse of Mineral That Is Plundered During Lactation and (Fully?) Replenished Afterwards. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihtonen, K.; Korhonen, P.; Isojärvi, J.; Ojala, R.; Ashorn, U.; Ashorn, P.; Tammela, O. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy and maternal and offspring bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2021, 1509, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Tian, J.; Winzenberg, T.; Wu, F. Calcium supplementation for improving bone density in lactating women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelamegham, S.; Mahal, L.K. Multi-level regulation of cellular glycosylation: from genes to transcript to enzyme to structure. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016, 40, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durin, Z.; Houdou, M.; Legrand, D.; Foulquier, F. Metalloglycobiology: The power of metals in regulating glycosylation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2023, 1867, 130412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulquier, F.; Legrand, D. Biometals and glycosylation in humans: Congenital disorders of glycosylation shed lights into the crucial role of Golgi manganese homeostasis. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2020, 1864, 129674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lönnerdal, B.; Hernell, O. An Opinion on “Staging” of Infant Formula. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 62, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegar, B.; Wibowo, Y.; Basrowi, R.W.; Ranuh, R.G.; Sudarmo, S.M.; Munasir, Z.; Atthiyah, A.F.; Widodo, A.D.; Supriatmo, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Kadim, M.; et al. The Role of Two Human Milk Oligosaccharides, 2′-Fucosyllactose and Lacto-N-Neotetraose, in Infant Nutrition. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2019, 22, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, C.P.; Brownbill, P.; Dilworth, M.; Glazier, J.D. Review: Adaptation in placental nutrient supply to meet fetal growth demand: Implications for programming. Placenta 2010, 31, S70–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runnels, L.W.; Komiya, Y. TRPM6 and TRPM7: Novel players in cell intercalation during vertebrate embryonic development. Dev. Dyn. 2020, 249, 912–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiya, Y.; Su, L.-T.; Chen, H.-C.; Habas, R.; Runnels, L.W. Magnesium and embryonic development. Magnes. Res. 2014, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Shinohara, A.; Matsukawa, T.; Chiba, M.; Wu, J.; Iesaki, T.; Okada, T. Chronic magnesium deficiency decreases tolerance to hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in mouse heart. Life Sci. 2011, 88, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Jauniaux, E. The human placenta: new perspectives on its formation and function during early pregnancy. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2023, 290, 20230191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, R.N.; Cuffe, J.; Moritz, K.; Paravicini, T. Maternal hypomagnesemia causes placental abnormalities and fetal and postnatal mortality. Placenta 2015, 36, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, J.; Gupta, M.; McGill, M.; Xue, X.; Chatterjee, P.; Yoshida-Hay, M.; Robeson, W.; Metz, C. Magnesium deficiency during pregnancy in mice impairs placental size and function. Placenta 2016, 39, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocylowski, R.; Grzesiak, M.; Gaj, Z.; Lorenc, W.; Bakinowska, E.; Barałkiewicz, D.; von Kaisenberg, C.S.; Lamers, Y.; Suliburska, J. Associations between the Level of Trace Elements and Minerals and Folate in Maternal Serum and Amniotic Fluid and Congenital Abnormalities. Nutrients 2019, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/why-we-need-to-talk-about-losing-a-baby. Accessed 1 October 2024.

- Sami, A.S.; Suat, E.; Alkis, I.; Karakus, Y.; Guler, S. The role of trace element, mineral, vitamin and total antioxidant status in women with habitual abortion. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2019, 34, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.-I.; Cardenas, A.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Zota, A.R.; Hivert, M.-F.; Aris, I.M.; Sanders, A.P. Non-essential and essential trace element mixtures and kidney function in early pregnancy – A cross-sectional analysis in project viva. Environ. Res. 2022, 216, 114846–114846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenhouse, C.; Suva, L.J.; Gaddy, D.; Wu, G.; Bazer, F.W. Phosphate, Calcium, and Vitamin D: Key Regulators of Fetal and Placental Development in Mammals. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2022, 1354, 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothen, J.-P.; Rutishauser, J.; Arnet, I.; Allemann, S.S. Renal insufficiency and magnesium deficiency correlate with a decreased formation of biologically active cholecalciferol: a retrospective observational study. Pharm. Weekbl. 2022, 45, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.A.; Siadat, S.; Main, E.K.; Huybrechts, K.F.; El-Sayed, Y.Y.; Hlatky, M.A.; Atkinson, J.; Sujan, A.; Bateman, B.T. Chronic Hypertension During Pregnancy: Prevalence and Treatment in the United States, 2008–2021. Hypertension 2024, 81, 1716–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, J.S.; Ananth, C.V. Chronic Hypertension: A Neglected Condition but With Emerging Importance in Obstetrics and Beyond. Hypertension 2024, 81, 1724–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosanoff, A.; Costello, R.B.; Johnson, G.H. Effectively Prescribing Oral Magnesium Therapy for Hypertension: A Categorized Systematic Review of 49 Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2021, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. RE: Petition for a qualified health claim for magnesium and reduced risk of high blood pressure (hypertension) (docket No. FDA-2016-Q-3770). January 10, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/155304/download?attachment.

- Saris, N.-E.L.; Mervaala, E.; Karppanen, H.; Khawaja, J.A.; Lewenstam, A. Magnesium: An update on physiological, clinical and analytical aspects. Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 294, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, M.J.; Granfeldt, A.; Andersen, L.W. Bicarbonate, calcium, and magnesium for in-hospital cardiac arrest – An instrumental variable analysis. Resuscitation 2023, 191, 109958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn, M.K.; Bailey, D.; Balion, C.; Cembrowski, G.; Collier, C.; De Guire, V.; Higgins, V.; Jung, B.; Ali, Z.M.; Seccombe, D.; et al. Reference Interval Harmonization: Harnessing the Power of Big Data Analytics to Derive Common Reference Intervals across Populations and Testing Platforms. Clin. Chem. 2023, 69, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.I.; Brown, P.W. The Effects of Magnesium on Hydroxyapatite Formation In Vitro from CaHPO4 and Ca4(PO4)2O at 37.4°C. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1997, 60, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, F.W.; Stanton, M.F. Serum magnesium levels in the United States, 1971-1974. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1986, 5, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía-Rodríguez, F.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Villalpando, S.; García-Guerra, A.; Humarán, I.M.-G. Iron, zinc, copper and magnesium deficiencies in Mexican adults from the National Health and Nutrition Survey 2006. Salud Publica De Mex. 2013, 55, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, P.S.; Nessim, S.J. Clinical aspects of magnesium physiology in patients on dialysis. Semin. Dial. 2017, 30, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, R.B.; Elin, R.J.; Rosanoff, A.; Wallace, T.C.; Guerrero-Romero, F.; Hruby, A.; Lutsey, P.L.; Nielsen, F.H.; Rodriguez-Moran, M.; Song, Y.; et al. Perspective: The Case for an Evidence-Based Reference Interval for Serum Magnesium: The Time Has Come. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 977–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosanoff, A. Perspective: US Adult Magnesium Requirements Need Updating: Impacts of Rising Body Weights and Data-Derived Variance. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2020, 12, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, R.; Shindo, Y.; Oka, K. Magnesium Is a Key Player in Neuronal Maturation and Neuropathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workinger, J.L.; Doyle, R.P.; Bortz, J. Challenges in the Diagnosis of Magnesium Status. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenders, N.H.J.; Vervloet, M.G. Magnesium: A Magic Bullet for Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease? Nutrients 2019, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Chen, R.; Zheng, W.; Guo, C.; Lu, L.; Ji, X.; Chi, Z.; Yu, J. Association Between Serum Magnesium and Anemia: China Health and Nutrition Survey. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2014, 159, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Wal-Visscher, E.R.; Kooman, J.P.; van der Sande, F.M. Magnesium in Chronic Kidney Disease: Should We Care? Blood Purif. 2018, 45, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasdam, S.-M.; Glasdam, S.; Peters, G.H. The Importance of Magnesium in the Human Body: A Systematic Literature Review. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2016, 73, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akizawa, Y.; Koizumi, S.; Itokawa, Y.; Ojima, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Tamura, T.; Kusaka, Y. Daily Magnesium Intake and Serum Magnesium Concentration among Japanese People. J. Epidemiology 2008, 18, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino, P.; Netti, L.; Mariani, M.V.; Maraone, A.; D’aMato, A.; Scarpati, R.; Infusino, F.; Pucci, M.; Lavalle, C.; Maestrini, V.; et al. Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Screening for Magnesium Deficiency. Cardiol. Res. Pr. 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, A.S.; Bressendorff, I.; Nordholm, A.; Egstrand, S.; Jørgensen, N.R.; Klausen, T.W.; Olgaard, K.; Hansen, D.; Jacobsen, A.A. Diurnal variation of magnesium and the mineral metabolism in patients with chronic kidney disease. Bone Rep. 2021, 15, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, M.S. Magnesium: Are We Consuming Enough? Nutrients 2018, 10, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosanoff, A.; Weaver, C.M.; Rude, R.K. Suboptimal magnesium status in the United States: are the health consequences underestimated? Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosanoff, A.; West, C.; Elin, R.J.; Micke, O.; Baniasadi, S.; Barbagallo, M.; Campbell, E.; Cheng, F.-C.; Costello, R.B.; Gamboa-Gomez, C.; et al. Recommendation on an updated standardization of serum magnesium reference ranges. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 3697–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micke, O.; Vormann, J.; Kraus, A.; Kisters, K. Serum magnesium: time for a standardized and evidence-based reference range. Magnes Res. 2021, 34, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micke, O.; Vormann, J.; Classen, H.-G.; Kisters, K. Magnesium: Bedeutung für die hausärztliche Praxis – Positionspapier der Gesellschaft für Magnesium-Forschung e. V. DMW - Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2020, 145, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Wang, X.-F.; Li, D.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Zhao, L.-J.; Liu, X.-G.; Guo, Y.-F.; Shen, J.; Lin, X.; Deng, J.; et al. The good, the bad, and the ugly of calcium supplementation: a review of calcium intake on human health. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 2443–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver CM, Heaney RP. Food sources, supplements, and bioavailability. Chapter 9, pp. 129-142 in: Calcium in Human Health, Weaver CM, Heaney RP, Eds. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, 2006.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendation on calcium supplementation before pregnancy for the prevention of pre-eclampsia and its complications. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- National Institutes of Health. Magnesium Fact Sheet for Professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Magnesium-HealthProfessional/?print=1. Accessed 8 August 2024.

- Spätling, L.; Classen, H.G.; Kisters, K.; Liebscher, U.; Rylander, R.; et al. Supplementation of magnesium in pregnancy. J Preg Child Health. 2017, 4, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parazzini, F.; Di Martino, M.; Pellegrino, P. Magnesium in the gynecological practice: a literature review. Magnes. Res. 2017, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Qu, S.; Chen, Y.; Fang, J.; Song, X.; He, K.; Jiang, K.; Sun, X.; Shi, J.; Tao, Y.; et al. Associations of the magnesium depletion score and magnesium intake with diabetes among US adults: an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2018. Epidemiology Heal. 2024, 46, e2024020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repke, J.T. Calcium, Magnesium, and Zinc Supplementation and Perinatal Outcome. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991, 34, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čabarkapa, V.; Bogavac, M.; Jakovljević, A.; Pezo, L.; Nikolić, A.; Belopavlović, Z.; Mirjana, D. Serum magnesium level in the first trimester of pregnancy as a predictor of pre-eclampsia – a pilot study. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2018, 37, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo-Monge, M.F.; Barrado, E.; Parodi-Román, J.; Escobedo-Monge, M.A.; Torres-Hinojal, M.C.; Marugán-Miguelsanz, J.M. Magnesium Status and Ca/Mg Ratios in a Series of Children and Adolescents with Chronic Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosanoff, A.; West, C.; Elin, R.J.; Micke, O.; Baniasadi, S.; Barbagallo, M.; Campbell, E.; Cheng, F.-C.; Costello, R.B.; Gamboa-Gomez, C.; et al. Recommendation on an updated standardization of serum magnesium reference ranges. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 3697–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.; Marshall, K.; Zagorin, S.; Devarshi, P.P.; Mitmesser, S.H. Socioeconomic Inequalities Impact the Ability of Pregnant Women and Women of Childbearing Age to Consume Nutrients Needed for Neurodevelopment: An Analysis of NHANES 2007–2018. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, C.; Aaseth, J.O. Magnesium: a scoping review for Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, P.M.; Marcelino, G.; Santana, L.F.; de Almeida, E.B.; Guimarães, R.d.C.A.; Pott, A.; Hiane, P.A.; Freitas, K.d.C. Minerals in Pregnancy and Their Impact on Child Growth and Development. Molecules 2020, 25, 5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, T.; Lin, X.; Jing, X.; Zhang, J. Oral Magnesium Supplementation for the Prevention of Preeclampsia: a Meta-analysis or Randomized Controlled Trials. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2021, 200, 3572–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makrides, M.; Crosby, D.D.; Shepherd, E.; A Crowther, C.; Bain, E.; Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. Magnesium supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2019, CD000937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Song, G.; Zhao, G.; Meng, T. Effect of oral magnesium supplementation for relieving leg cramps during pregnancy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 60, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunabalasingam, S.; Slizys, D.D.A.L.; Quotah, O.; Magee, L.; White, S.L.; Rigutto-Farebrother, J.; Poston, L.; Dalrymple, K.V.; Flynn, A.C. Micronutrient supplementation interventions in preconception and pregnant women at increased risk of developing pre-eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 77, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.; Flynn, A.; Cashman, K. The effect of magnesium supplementation on biochemical markers of bone metabolism or blood pressure in healthy young adult females. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 53, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubero, M.B.; Llop, S.; Irizar, A.; Murcia, M.; Molinuevo, A.; Ballester, F.; Levi, M.; Lozano, M.; Ayerdi, M.; Santa-Marina, L. Serum metal levels in a population of Spanish pregnant women. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 36, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCowan, L.M.; Figueras, F.; Anderson, N.H. Evidence-based national guidelines for the management of suspected fetal growth restriction: comparison, consensus, and controversy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, S855–S868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, C.A.L.; Ray, J.G.; Figueiroa, J.N.; Alves, J.G. BRAzil magnesium (BRAMAG) trial: a double-masked randomized clinical trial of oral magnesium supplementation in pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarjan, A.; Zarean, E. Effect of Magnesium Supplement on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Randomized Control Trial. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2017, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, L.M.; Fhloinn, D.M.N.; Gaydadzhieva, G.T.; Mazurkiewicz, O.M.; Leeson, H.; Wright, C.P. Magnesium in pregnancy. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, T.; Liu, Y.; Koivisto, A.; Virtanen, S.; Luoto, R. Effects of dietary counselling on micronutrient intakes in pregnant women in Finland. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlova, S.; Dikke, G.; Pickering, G.; Djobava, E.; Konchits, S.; Starostin, K. Magnesium level correlation with clinical status and quality of life in women with hormone related conditions and pregnancy based on real world data. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelverton, C.A.; Rafferty, A.A.; Moore, R.L.; Byrne, D.F.; Mehegan, J.; Cotter, P.D.; Van Sinderen, D.; Murphy, E.F.; Killeen, S.L.; McAuliffe, F.M. Diet and mental health in pregnancy: Nutrients of importance based on large observational cohort data. Nutrition 2022, 96, 111582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, S.A.; Brown, A.R.; Camargo, J.T.; Kerling, E.H.; Carlson, S.E.; Gajewski, B.J.; Sullivan, D.K.; Valentine, C.J. Micronutrient Gaps and Supplement Use in a Diverse Cohort of Pregnant Women. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, K.; Dastidar, R.G.; Aroor, A.R.; Rao, M.; Shetty, S.; Poojari, V.G.; Bs, V. Micronutrients in Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. F1000Research 2024, 11, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, P.-J.; Liao, C.-Y.; Kao, Y.-H.; Chan, J.-S.; Lin, Y.-F.; Chuu, C.-P.; Chen, J.-S. Comparison of fractional excretion of electrolytes in patients at different stages of chronic kidney disease. Medicine 2020, 99, e18709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Period | Calcium (mmol/L) | Magnesium (mmol/L) | Phosphate (mmol/L)1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit* | Upper Limit* | Lower Limit* | Upper Limit* | Lower Limit* | Upper Limit* | |

| Week 7–17 | 2.18 (2.12–2.23) | 2.53 (2.50–2.57) | 0.70 (0.69–0.71) | 0.96 (0.88–1.059) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | 1.65 (1.43–1.86) |

| Week 17–24 | 2.08 (2.04–2.11) | 2.45 (2.41–2.50) | 0.66 (0.65–0.66) | 0.87 (0.84–0.90) | 0.84 (0.74–0.95) | 1.45 (1.41–1.48) |

| Week 24–28 | 2.04 (1.99–2.08) | 2.40 (2.36–2.43) | 0.63 (0.63–0.63) | 0.91 (0.86–0.97) | 0.81 (0.67–0.95) | 1.47 (1.43–1.51) |

| Week 28–31 | 2.07 (2.03–2.11) | 2.41 (2.33–2.49) | 0.63 (0.63–0.64) | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | 0.77 (0.70–0.85) | 1.44 (1.38–1.49) |

| Week 31–34 | 2.05 (1.99–2.10) | 2.38 (2.37–2.40) | 0.64 (0.64–0.64) | 0.90 (0.84–0.97) | 0.84 (0.72–0.95) | 1.42 (1.35–1.49) |

| Week 34–38 | 2.04 (1.96–2.11) | 2.41 (2.39–2.43) | 0.57 (0.50–0.65) | 0.87 (0.84–0.90) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | 1.50 (1.43–1.57) |

| Predelivery | 1.98 (1.91–2.05) | 2.46 (2.42–2.50) | 0.64 (0.63–0.65) | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | 1.50 (1.43–1.57) |

| Postpartum | 2.06 (1.90–2.22) | 2.57 (2.51–2.63) | 0.68 (0.66–0.71) | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 1.80 (1.62–1.99) |

| Gestation (Days) | Gestation (Weeks) | No. of Women | Mean [Mg], mEq/L | SD | Plasma Volume (mL) | Corrected Conc. Mg (mEq/L) | Conc. Mg (mmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~30 | ~4 | 5 | 1.873 | 0.104 | 2644 | 1.834 | 0.92 |

| 31-60 | 4-9 | 12 | 1.826 | 0.103 | 2643 | 1.787 | 0.89 |

| 61-90 | 9-13 | 28 | 1.728 | 0.091 | 2770 | 1.773 | 0.89 |

| 91-120 | 13-17 | 29 | 1.694 | 0.139 | 3047 | 1.912 | 0.96 |

| 121-150 | 17-21 | 23 | 1.599 | 0.177 | 3305 | 1.957 | 0.98 |

| 151-180 | 21-26 | 23 | 1.558 | 0.104 | 3550 | 2.048 | 1.02 |

| 180-210 | 26-30 | 17 | 1.488 | 0.101 | 3769 | 2.077 | 1.04 |

| 211-240 | 30-34 | 9 | 1.526 | 0.121 | 3820 | 2.159 | 1.08 |

| 240-270 | 34-39 | 5 | 1.392 | 0.173 | 3658 | 1.882 | 0.94 |

| Normal Value | 2.087 | 0.067 | 2.087 | 1.04 |

| Category | Mineral content, mmol/L | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | P | Mg | ||

| A. Mothers who carried to term | ||||

| Human (Early lactation) | 7.4 | 3.9 | 1.4 | Sánchez [25] |

| Human (Late lactation) | 6.3 | 3.9 | 1.4 | |

| Human (Early lactation) | 6.9 | - | 1.0 | Li [26] |

| Human (Late lactation) | 6.6 | - | 0.9 | |

| Human (Established feeding) | 6.7 | - | 1.5 | |

| Human | 7 | 4.7 | 1.3 | Sanchez [26] |

| B. Mothers who delivered prematurely | ||||

| Human (Day 7 post-partum) | 6.1 | 4.7 | 1.3 | Gates [27] |

| Human (Day 14 post-partum) | 5.6 | 4.6 | 1.2 | |

| Human (Day 21 post-partum) | 5.5 | 4.4 | 1.2 | |

| Human (Day 28 post-partum) | 5.3 | 4.1 | 1.4 | |

| The values in this table are means and do not reflect the reported standard deviations, confidence intervals, or the ranges of concentrations found. | ||||

| Period | Molar Ratio Ca:Mg | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LoCa:LoMg | HiCa:LoMg | HiCa:HiMg | LoCa:HiMg | |

| Week 7–17 | 3.11 | 3.61 | 2.64 | 2.27 |

| Week 17–24 | 3.15 | 3.71 | 2.82 | 2.39 |

| Week 24–28 | 3.24 | 3.81 | 2.64 | 2.24 |

| Week 28–31 | 3.29 | 3.83 | 2.65 | 2.27 |

| Week 31–34 | 3.20 | 3.72 | 2.64 | 2.28 |

| Week 34–38 | 3.58 | 4.23 | 2.77 | 2.34 |

| Predelivery | 3.09 | 3.84 | 2.62 | 2.11 |

| Postpartum | 3.03 | 3.78 | 2.60 | 2.08 |

| For mother with chronic Mg2+ deficiency | For child |

|---|---|

| Poor embryonic development Poor placental development Spontaneous abortion Declines in renal health Hypertension |

Inadequate intrauterine growth and development (Fetal Growth Restriction) Spontaneous pre-term birth |

| Late pregnancy complications (Not a focus of this review) | |

| Declines in mental health during pregnancy Pre-eclampsia and related side effects Placental abruption Declines in immune health Gestational diabetes Early time of delivery (pre-term delivery) Post-partum depression Post-partum recovery of bone mineral density |

Retarded organ development/fetal programming Congenital abnormalities Poor skeletal development |

| Risk: Failure to appropriately glycosylate lipid intermediates and proteins |

|

| Risk: Inability to meet nutrient demands retards embryonic development [39] |

|

| Risk: Aberrations in placental development |

|

| Risk: Spontaneous abortion |

|

| Risk: Declines in renal health |

|

| Risk: Inadequate biosynthesis of active Vitamin D3 |

|

| Risk: Essential Hypertension |

|

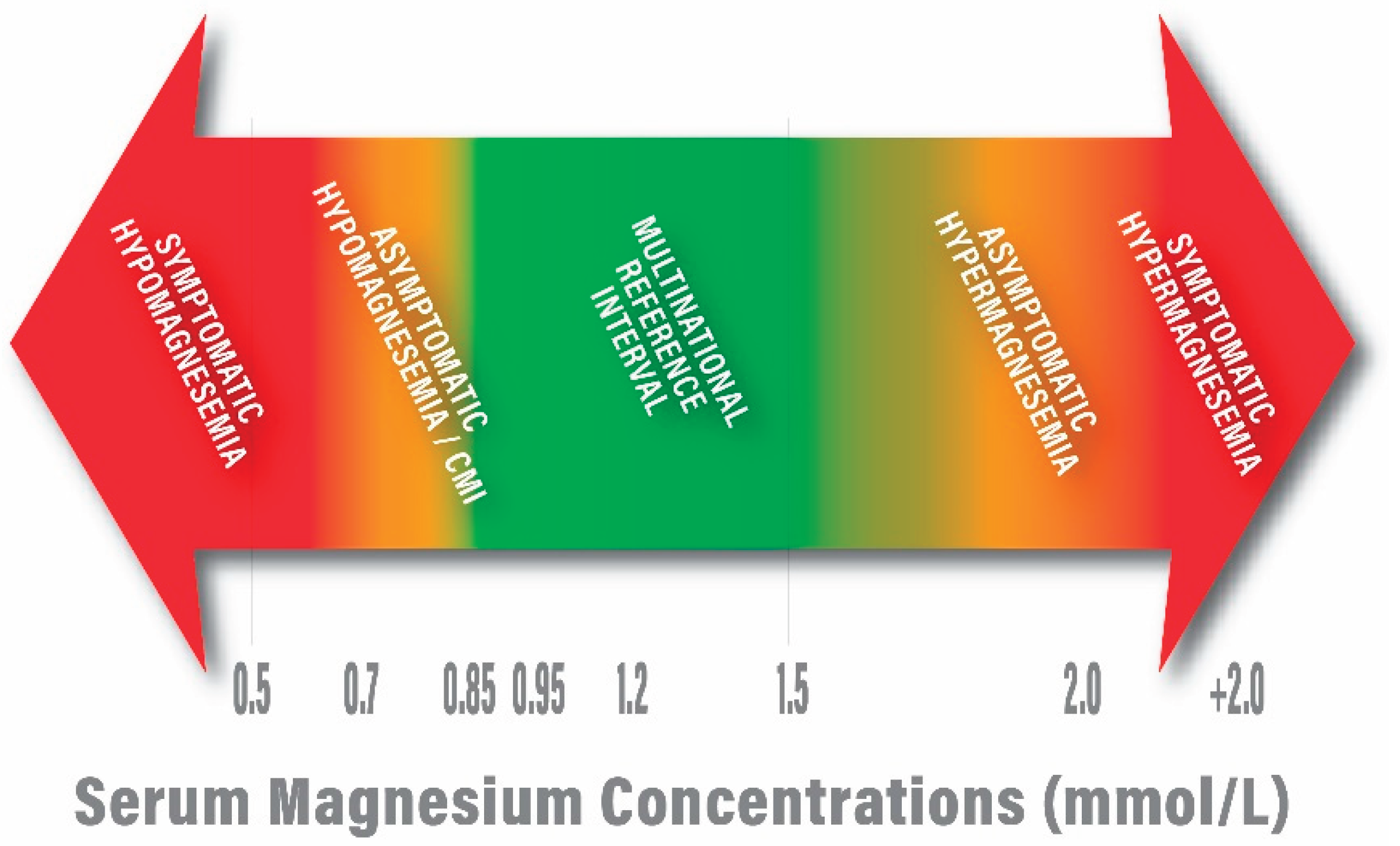

| 0.68-0.88 mmol/L [Martin 59] |

| 0.70 – 0.96 mmol/L [Lowenstein and Stanton 60] |

| 0.70 – 0.95 mmol/L [Mejía-Rodriguez 61] |

| 0.71 – 0.94 [Nordic reference interval, Larsson 14] |

| 0.7 – 1.0 mmol/L [a U.S. standard; Misra 62] |

| 0.85 – 0.96 mmol/L [Costello 63; Rosanoff 64] |

| 0.5 – 1.05 mmol/L [a Japanese standard; Yamanaka 65] |

| 0.7 – 1.0 mmol/L [Workinger 66] |

| 0.7 – 1.05 mmol/L [a European standard; Leenders 67] |

| 0.84 – 1.05 mmol/L [Zhan 68] |

| 0.7 – 1.1 mmol/L [Van de Wal-Visscher 69; Glasdam 70] |

| 0.54 – 1.19 mmol/L [Akizawa 71] |

| 0.76 – 1.15 mmol/L [a European standard; Severino 72] |

| 1. | Phosphorus data are included for reference. Phosphorus and calcium are interrelated because hormones, such as vitamin D and parathyroid hormone (PTH), regulate the metabolism of both minerals. In addition, phosphorus and calcium make up hydroxyapatite, the main structural component in bones and tooth enamel. In adults, normal phosphate concentration in serum or plasma is 2.5 to 4.5 mg/dL (0.81 to 1.45 mmol/L) [18]. |

| 2. | The reference ranges for serum calcium and serum magnesium vary but generally range from 2.2-2.7 mmol/L and 0.7-1.0 mmol/L, respectively. |

| 3. | Data related to serum creatinine concentrations in Stage 1 and 2 chronic kidney disease patients show increases in serum creatinine when kidney function is compromised [109]. Thus, the association of increased serum creatinine with risk of pre-eclampsia may reflect early changes in kidney function. |

| 4. | Magnesium citrate contains 11% magnesium by weight. If 300 mg of magnesium citrate was administered, the magnesium content was 34 mg. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).