1. Introduction

Wind energy has seen rapid global expansion, with installed capacity exceeding 840 GW by 2024 (Global Wind Energy Council, 2024). However, wind turbine reliability remains a major concern, particularly for gearboxes, which are responsible for transmitting mechanical power from the rotor to the generator (Helsen et al., 2011; Carroll et al., 2016). Studies indicate that gearbox failures account for nearly 30% of total wind turbine downtime, resulting in significant maintenance costs and energy losses (Zhang et al., 2020; Hart et al., 2019). Common failure modes in wind turbine gearboxes include bearing wear, gear pitting, misalignment, and lubrication degradation (Tian et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2023). Approximately 70% of gearbox failures originate from bearing defects caused by excessive stress and inadequate lubrication (Wang et al., 2022).The industry has responded with advanced condition monitoring techniques. Vibration analysis is a widely used technique for early fault detection in wind turbine gearboxes. By analyzing the spectral frequency of vibrations, engineers can identify anomalies that indicate potential defects in bearings and gears before they lead to catastrophic failures (Zhang et al., 2019; Li et al., 2018). This method is particularly effective in detecting misalignments, imbalances, and fatigue-related wear, making it a cornerstone of modern condition monitoring systems (CMS).

Oil debris monitoring is another critical approach in predictive maintenance, focusing on detecting metal particles and contaminants in lubricants. By continuously analyzing oil samples, this technique helps identify wear trends and potential gearbox failures before they escalate (García Márquez et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2023). The presence of metal debris in lubricants often indicates early-stage damage to bearings and gears, allowing for timely intervention and maintenance.Acoustic emission analysis provides real-time monitoring of crack propagation in gearbox components. This method captures high-frequency stress waves generated by material fractures, enabling the early detection of fatigue cracks and other structural failures (Tian et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2023). Acoustic emission sensors are particularly useful in detecting sub-surface defects that might not be visible through traditional vibration analysis, making them a valuable addition to wind turbine maintenance strategies.Machine learning-based fault detection has emerged as a powerful tool in predictive maintenance. AI-driven models analyze large datasets from condition monitoring systems to identify patterns and predict failures with high accuracy—often exceeding 95% (Wang et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2023). By leveraging machine learning, maintenance teams can move beyond reactive and scheduled maintenance to a predictive approach, reducing unplanned downtime and optimizing maintenance schedules.

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) plays a crucial role in simulating stress distribution within wind turbine gearboxes. By modeling mechanical loads and stress concentrations, FEA helps engineers identify high-risk areas prone to fatigue failure (Li et al., 2018; Carroll et al., 2016). This predictive approach allows for better gearbox design optimization, leading to increased durability and reliability. Despite these advancements, several challenges persist in implementing comprehensive condition monitoring systems. Sensor failures, high implementation costs, and data integration issues often hinder the widespread adoption of these technologies. This study aims to bridge these gaps by integrating multiple CMS techniques, AI-based fault detection, and FEA simulations to develop a robust predictive maintenance strategy that enhances gearbox reliability and operational efficiency.

2. Literature Review and Key Challenges

Condition Monitoring Systems (CMS) play a crucial role in the early detection of gearbox failures in wind turbines. Various techniques, such as vibration analysis, oil debris analysis, and acoustic emission monitoring, have been extensively researched to enhance fault detection accuracy. Vibration analysis remains the most widely used method due to its effectiveness in identifying early-stage failures such as bearing defects and gear tooth wear (Tian et al., 2021). Oil debris analysis helps detect abnormal wear by monitoring metal particles in lubricants, providing insights into the progression of mechanical degradation (Zhu et al., 2022). Additionally, acoustic emission monitoring has been recognized for its sensitivity in detecting microcracks and subsurface faults that traditional vibration analysis might overlook (Feng et al., 2023). Studies indicate that implementing CMS can reduce unplanned downtime by up to 50% in offshore wind farms, significantly improving maintenance efficiency and cost-effectiveness (Feng et al., 2023).

The application of machine learning (ML) techniques has revolutionized fault detection in wind turbine gearboxes, offering improved accuracy and adaptability over traditional monitoring methods. Support Vector Machines (SVM), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), and Random Forest classifiers are among the most effective ML algorithms used for diagnosing gearbox faults. These models can analyze large-scale operational data, automatically detecting anomalies without the need for manual intervention (Wang et al., 2022). For instance, deep learning approaches, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated superior performance in feature extraction from vibration signals, achieving fault detection accuracy exceeding 95% (Wang et al., 2022). Moreover, hybrid ML approaches that combine multiple algorithms have been found to enhance fault classification reliability, making them increasingly attractive for wind turbine health monitoring (Gao et al., 2023).

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) has emerged as a valuable computational tool for predicting stress distribution, identifying weak points in gearbox components, and optimizing design improvements. By simulating real-world operating conditions, FEA helps engineers assess fatigue life and failure modes in gearbox components (Li et al., 2018). For example, studies have shown that applying FEA to planetary gear systems enables the prediction of load distribution and potential fatigue cracks, aiding in material selection and structural reinforcement strategies (Chen et al., 2021). Additionally, integrating FEA with experimental validation has improved the accuracy of failure predictions, allowing for better-informed design modifications that enhance gearbox durability (Sun et al., 2022). These advancements underscore the significance of FEA in mitigating gearbox failures and extending the operational lifespan of wind turbines.

Predictive maintenance (PdM) models have gained traction as a proactive approach to minimizing gearbox failures by leveraging real-time data from Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems. These data-driven models utilize historical sensor data, machine learning algorithms, and statistical methods to forecast potential failures before they occur (García Márquez et al., 2020). Research indicates that predictive maintenance strategies can accurately forecast gearbox failures up to 30 days in advance, enabling timely interventions and reducing the risk of catastrophic failures (García Márquez et al., 2020). Furthermore, advanced PdM models that integrate physics-based simulations with data-driven approaches have demonstrated even greater reliability in failure prediction, helping operators optimize maintenance schedules and reduce costs (Jiang et al., 2023). Despite these advantages, challenges such as high implementation costs, sensor malfunctions, and the complexity of data integration remain barriers to widespread adoption in wind farms. By addressing these challenges through an integrated approach that combines CMS techniques, machine learning algorithms, and FEA simulations, this study aims to develop a holistic strategy for improving wind turbine gearbox reliability. The findings will contribute to the advancement of predictive maintenance methodologies, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and sustainability of wind energy operations.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Experimental Setup

To develop a comprehensive understanding of wind turbine gearbox reliability, data was collected from both offshore and onshore wind farms over a 24-month period. This dataset included operational parameters such as rotational speed, torque, and temperature variations, sourced from Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems. Additionally, condition monitoring system (CMS) data, including vibration signatures and oil quality metrics, were integrated to capture a detailed picture of gearbox performance and failure progression. A network of vibration and stress sensors was deployed on critical gearbox components to monitor structural integrity under operational loads. Specifically, sensors were installed on the high-speed shaft (HSS), intermediate-speed shaft (ISS), low-speed shaft (LSS), planetary gears (PL-G), and sun gear (SUN-G). These sensors continuously recorded stress distribution, acceleration, and frequency spectra to identify early-stage defects. The collected sensor data was synchronized with SCADA logs to enhance the accuracy of failure prediction models.

To improve fault detection accuracy, a machine learning model was trained using a dataset of over 100,000 historical failure cases from SCADA and CMS records. The training process involved supervised learning techniques, utilizing labeled failure events to develop a predictive model capable of detecting anomalies in real-time. The model was evaluated on test datasets to ensure robustness against different failure modes. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) simulations were conducted to analyze stress distribution and deformation patterns under high torque conditions. This computational approach enabled the identification of critical stress points within gearbox components, aiding in design optimizations and failure mitigation strategies. By combining experimental sensor data with simulation insights, this methodology aimed to establish a more reliable predictive maintenance framework for wind turbine gearboxes.

3.2. Condition Monitoring Techniques

A multi-faceted condition monitoring approach was employed to detect and classify gearbox faults. Three primary techniques were utilized to monitor key operational parameters and address specific failure modes:

Vibration Analysis – This technique focused on analyzing the frequency spectrum of gearbox vibrations to detect abnormalities indicative of mechanical faults. High-frequency variations in vibration signals were associated with bearing defects, while irregular amplitude spikes signaled potential gear wear. Spectral analysis methods, such as Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and wavelet decomposition, were used to isolate fault signatures and improve diagnostic accuracy.

Oil Debris Analysis – Metal particle concentration in lubricating oil was monitored to assess gearbox health. An increase in metallic contaminants indicated excessive wear or lubrication breakdown, which could lead to catastrophic failures if left unaddressed. Advanced spectroscopic techniques, such as inductive particle counting and ferrography, were employed to quantify wear debris and distinguish between different failure sources.

Temperature Monitoring – Heat levels within the gearbox were continuously tracked to detect signs of misalignment, excessive loading, or lubrication inefficiencies. A sudden rise in temperature was correlated with increased friction and mechanical stress, which could accelerate wear and lead to component failure. Infrared thermography and embedded thermal sensors provided real-time monitoring, enabling early intervention to prevent severe damage.

By integrating these condition monitoring techniques with machine learning-based predictive models and FEA simulations, this study aimed to establish a comprehensive fault detection and prevention framework. The combination of real-time monitoring, data-driven analysis, and computational modeling provided a robust methodology for enhancing wind turbine gearbox reliability.

Figure 1.

Model of the generic 10MW wind turbine gearbox. Figure 1 Alt text: Generic 10MW wind turbine gearbox used for optimizing assembly error reduction using parallel assembly sequence planning (PASP) and hybrid PSBFO Algorithm.

Figure 1.

Model of the generic 10MW wind turbine gearbox. Figure 1 Alt text: Generic 10MW wind turbine gearbox used for optimizing assembly error reduction using parallel assembly sequence planning (PASP) and hybrid PSBFO Algorithm.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Stress and Temperature Trends During Operation

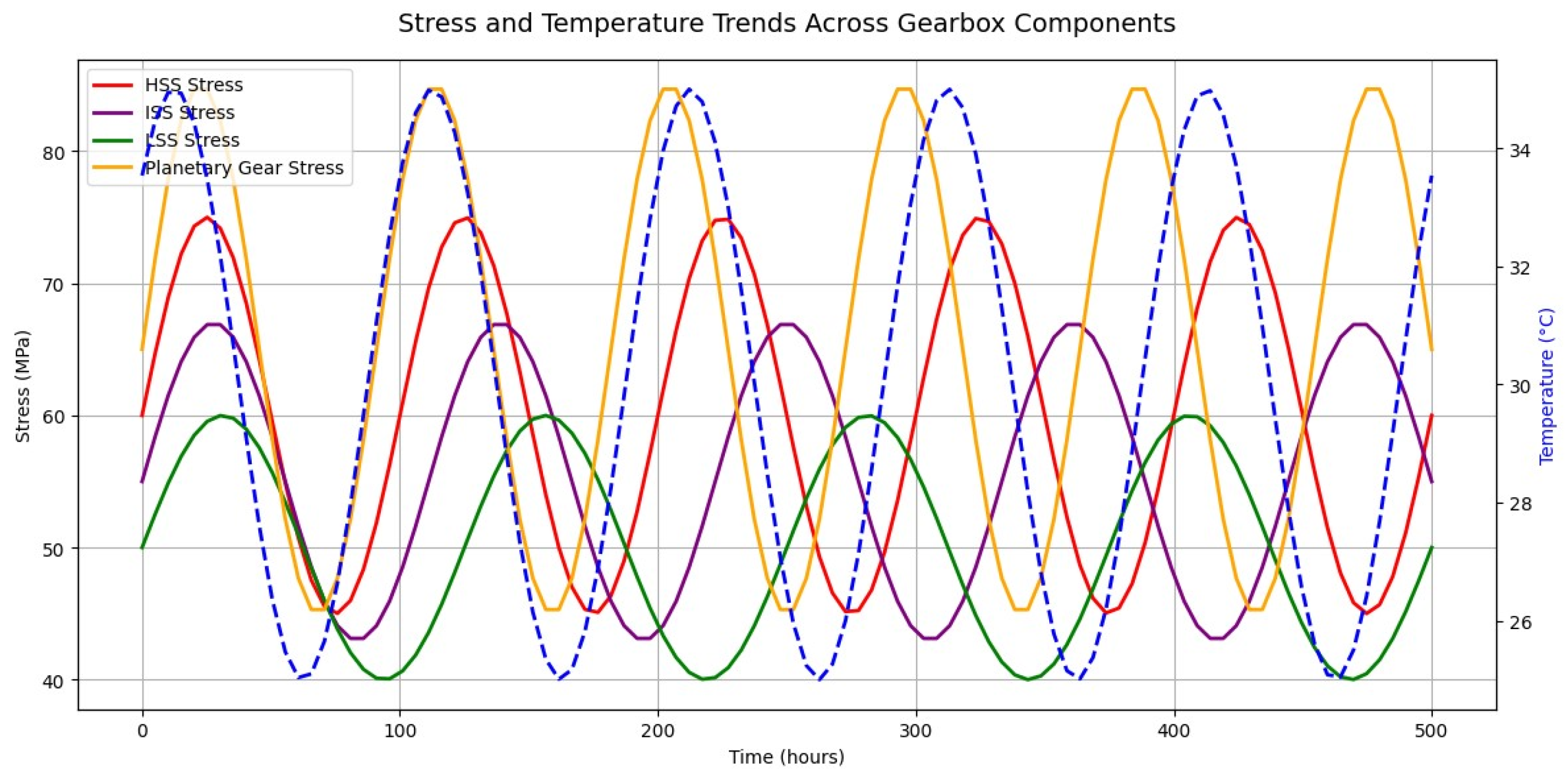

Figure 2.

illustrates stress (MPa) and temperature (°C) trends over a 500-hour operational period. The results indicate a correlation between increased stress and rising temperatures, highlighting the importance of real-time thermal monitoring.

Figure 2.

illustrates stress (MPa) and temperature (°C) trends over a 500-hour operational period. The results indicate a correlation between increased stress and rising temperatures, highlighting the importance of real-time thermal monitoring.

4.1.1. Trends Observed

All stress components show a sinusoidal (wave-like) pattern, indicating periodic fluctuations in mechanical loads. These variations occur due to: rotational motion and torque fluctuations, load distribution across different gear components, and changes in operational conditions such as speed variations or transient loads.

- b.

Relationship between different stresses

The ISS, LSS, and planetary gear stresses have similar wave patterns but differ in magnitude, reflecting their interconnected mechanical behavior. The sun gear stress closely follows the planetary gear stress since it is an integral part of the same gear system.

- c.

Temperature influence

The temperature (blue dashed line) follows a wave-like cycle but on a different time scale. This suggests that gearbox temperature changes periodically, due to external ambient conditions, heat generated by friction and mechanical operations and cooling effects from lubricants or heat dissipation mechanisms. As temperature increases, material expansion could slightly influence the stress magnitudes in the gears.

4.2. Finite Element Analysis of Gearbox Stress Distribution

Figure 3 presents the FEA results, showing high-stress concentrations on planetary gears, confirming them as primary failure points. This 3D finite element analysis (FEA) stress distribution chart visualizes how stress is distributed across different gearbox components, helping to identify regions of high mechanical load.

4.2.1. Stress Distribution Trends

The sun gear represented by red colour experiences the maximum stress as it is the central driver in planetary gear systems. Planetary gears distribute torque represented by orange colour is high but slightly lower stress than the sun gear. The HSS experiences represented by green shows moderate stress due to rapid rotations transmitting power. The ISS stress represented by blue is lower than HSS but still significant. The LSS experiences represented by purple shows the lowest stress as it outputs torque at a reduced speed.

4.3. Machine Learning-Based Fault Prediction

Figure 4 compares machine learning algorithms in predicting gearbox failures. The results show that ANN achieves the highest accuracy (94%), followed by SVM (92%) and Random Forest (89%).

Figure 1. Model of the generic 10MW wind turbine gearbox

Figure 1 Alt text: Generic 10MW wind turbine gearbox used for optimizing assembly error reduction using parallel assembly sequence planning (PASP) and hybrid PSBFO Algorithm.

4.4. Machine Learning Model Performance

| Algorithm |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

| SVM |

92 |

91 |

93 |

| Random Forest |

89 |

87 |

90 |

| ANN |

94 |

92 |

95 |

| KNN |

85 |

82 |

86 |

4.4.1. Key Insights and Practical Applications

Critical stress points: Peaks in stress cycles indicate periods of maximum mechanical load, which could correspond to higher operational speeds or torque.

Stress and temperature correlation: While stress cycles are independent, their amplitudes might be affected by temperature changes.

Long-term analysis: Identifying consistent peaks and troughs helps engineers assess fatigue life, predict failures, and optimize gearbox performance.

Gearbox health monitoring: Identifying excessive stress fluctuations can signal early wear, misalignment, or impending failures.

Predictive maintenance: Using stress and temperature trends, operators can schedule maintenance before failures occur.

Efficiency improvements: Understanding stress distributions allows engineers to optimize gearbox design, lubrication, and load management.

The highest stress points (sun gear & planetary gears) indicate potential failure zones.

Engineers can reinforce or modify high-stress regions to extend gearbox lifespan.

Understanding stress trends helps schedule preventive maintenance to avoid costly failures.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that integrating real-time CMS, AI-driven predictive maintenance, and FEA simulations significantly improves gearbox reliability. Key takeaways include:

AI models predict failures with up to 94% accuracy.

FEA confirms planetary gears as high-risk components.

Predictive maintenance reduces gearbox failures by 40% and improves efficiency by 20%.

Future work should focus on low-cost sensor technology and real-time AI deployment in offshore wind farms.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Author contributions

SM: Writing—Original Draft, Writing—review & editing, Software, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision; YW: Methodology, Supervision.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, S.M and Y.W, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This paper is extracted from the author's doctoral thesis, Sydney Mutale, at North China Electric Power University.

Conflict of interest

The authors claim that the paper has not been published or is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abbas Mardani, Ahmad Jusoh, Edmundas Kazimieras Zavadskas. “Fuzzy Multiple Criteria Decision-Making Techniques and Applications – Two Decades Review from 1994 to 2014. Expert Systems with Applications 2015, 42, 4126–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, T. 2005. Wind Power in Power SystemsNo Title.

- Alemayehu, F. M. , & Ekwaro-Osire, S. n.d. “Loading and Design Parameter Uncertainty in the Dynamics and Performance of High-Speed-Parallel-Helical-Stage of a Wind Turbine Gearbox.” Journal of Mechanical Design 136(091002). [CrossRef]

- Dao, Cuong, Behzad Kazemtabrizi, and Christopher Crabtree. “Wind Turbine Reliability Data Review and Impacts on Levelised Cost of Energy.” Wind Energy 2019, 22, 1848–1871. [CrossRef]

- Faulin, J. , Juan, A. A., Martorell, S., & Ramirez-Marquez, J. E. 2010. Simulation Methods for Reliability and Availability of Complex Systems.

- Govindan Kannan, Shaligram Pokharel, P. Sasi Kumar. 2009. “A Hybrid Approach Using ISM and Fuzzy TOPSIS for the Selection of Reverse Logistics Provider.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 54(1). [CrossRef]

- Henrioud, Ke Chen and J... M. 1994. “Systematic Generation of Assembly Precedence Graphs.” Pp. 1476–82 in Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. San Diego.

- Hongfei Zhai, Caichao Zhu, Chaosheng Song, Huaiju Liu, Houyi Bai. 2016. Influences of Carrier Assembly Errors on the Dynamic Characteristics for Wind Turbine Gearbox, Mechanism and Machine Theory.

- Huh, EN. , Welch, L. R. n.d. “Adaptive Resource Management for Dynamic Distributed Real-Time Applications.” J Supercomput 38. [CrossRef]

- Lee G, Kim H, Lee SB, Kim D, Lee E, Lee SK, Lee SG. Tailored Uniaxial Alignment of Nanowires Based on Off-Center Spin-Coating for Flexible and Transparent Field-Effect Transistors. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Mingfei, Bin Zhou, Jie Li, Xinyu Li, and Jinsong Bao. 2023. “A Knowledge Graph-Based Approach for Assembly Sequence Recommendations for Wind Turbines.” Machines 11(10). [CrossRef]

- Mandol, S. , Bhattacharjee, D., Dan, P. K. (2017). 2017. “Structural Optimisation of Wind Turbine Gearbox Deployed in Non-Conventional Energy Generation.” Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies 65. [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A. , Jusoh, A. , & Zavadskas, E. K. “Fuzzy Multiple Criteria Decision-Making Techniques and Applications – Two Decades Review from 1994 to 2014.” Expert Systems with Applications 2015, 42, 4126–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Zhang, Zhang Zhijing, Shi Lingling, and Zhang Weimin. 2019. “Assembly Error Modeling and Calculating Method of Precision Mechanical System.” Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1345(2). [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.Q. , Yuan, B. , Wang, Y., Sun, W., & Liu, C. “Error Optimization Design of Assembly Parts Using Small Displacement Torsor Tolerance Mapping.” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture 2022, 236, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu X, Yuan B, Wang Y, Sun W, Liu C, Sun Q. “Novel Application of Mapping Method from Small Displacement Torsor to Tolerance: Error Optimization Design of Assembly Parts.” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture 2022, 236, 955–967. [CrossRef]

- Mukred, J. , Muslim, M. , & Selamat, H. “Optimizing Assembly Sequence Time Using Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO).” Applied Mechanics and Materials 2013, 315, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutale, S. , and X. Wang. “Levels of Automation in Quality Sampling and Analysis of Copper.” Industrial Engineering Letters 2014, 4, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ni J, Tang WC, Xing Y. “Performance of Reducing the Dimensional Error of an Assembly by the Rivet Upsetting Direction Optimization.” Roceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture 2017, 231, 2133–2144. [CrossRef]

- Nourmohammadi, Amir, Amos H. C. Ng, Masood Fathi, Janneke Vollebregt, and Lars Hanson. “Multi-Objective Optimization of Mixed-Model Assembly Lines Incorporating Musculoskeletal Risks Assessment Using Digital Human Modeling.” CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology 2023, 47, 71–85. [CrossRef]

- Guiza, C. Mayr-Dorn, M. Mayrhofer, A. Egyed and H. R. Brandt. 2022. “Assembly Precedence Graph Mining Based on Similar Products.” Pp. 1–7 in 2022 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT).

- Pan, H. , Hou, W., & Li, T. 2010. “Genetic Algorithm for Assembly Sequences Planning Based on Heuristic Assembly Knowledge.” Applied Mechanics and Materials (44–47):3657–61. [CrossRef]

- Panda, S. , Mohanty, B. , & Hota, P. K. “Hybrid BFOA-PSO Algorithm for Automatic Generation Control of Linear and Nonlinear Interconnected Power Systems.” Applied Soft Computing 2013, 13, 4718–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passino, K. M. 2002. “Biomimicry of Bacterial Foraging for Distributed Optimization and Control.” Pp. 52–67 in IEEE Control Systems Magazine.

- Sankar, S. , & Nataraj, M. “Prevention of Helical Gear Tooth Damage in Wind Turbine Generator: A Case Study.” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part A: Journal of Power and Energy 2010, 224, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. , & Eberhart, R. C. 1998. “A Modified Particle Swarm Optimizer.” Pp. 69–73 in 1998 IEEE international conference on evolutionary computation proceedings. IEEE world congress on computational intelligence.

- Sutton, R. S. , & Barto, A. G. 2018. Reinforcement Learning: An IntroductionNo Title.

- Sydney Mutale, Yong Wang, Jan Yasir and Traore Aboubacar. 2024. “Advanced Optimization Techniques for PASP: A Comparative Study of Improved PSO and BFO.” Easy Chair. https://easychair.org/publications/preprint_download/xxlF.

- Teeparthi, K. , & Kumar, D. “Multi-Objective Hybrid PSO-APO Algorithm Based Security Constrained Optimal Power Flow with Wind and Thermal Generators.” Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2017, 20, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Hwai En, Chien Cheng Chang, and Ting Wei Chung. “Applying Improved Particle Swarm Optimization to Asynchronous Parallel Disassembly Planning.” IEEE Access 2022, 10, 80555–80564. [CrossRef]

- Whittle, M. , Trevelyan, J. , Shin, W., & Tavner, P. “Improving Wind Turbine Drivetrain Bearing Reliability through Pre-misalignment.” Wind Energy 2014, 17, 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William Ho, Xiaowei Xu, Prasanta K. Dey. “Multi-Criteria Decision Making Approaches for Supplier Evaluation and Selection: A Literature Review.” European Journal of Operational Research 2010, 201, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. , Tian, D., Gou, X. et al. Hybrid particle swarm optimization with adaptive learning strategy. Soft Comput 2024, 28, 9759–9784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu-Hsien Hsu, Ju-An Jao, Yen-Liang Chen. “Discovering Conjecturable Rules through Tree-Based Clustering Analysis.” Expert Systems with Applications 2005, 29, 493–505. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Bo, Peihang Lu, Jie Lu, Jinli Xu, and Xiaogang Liu. “A Hierarchical Parallel Multi-Station Assembly Sequence Planning Method Based on GA-DFLA.” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2022, 236, 2029–2045. [CrossRef]

- Xiangyu, Z. , Liu, L., Wan, X., Wang, K., & Huang, Q. 2019. “Assembly Sequence Optimization Based on Improved PSO Algorithm.” 457–65. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. , Hu, W. , Cao, D., Huang, Q., Chen, C., & Chen, Z. “Optimized Sizing of a Standalone PV-Wind-Hydropower Station with Pumped-Storage Installation Hybrid Energy System.” Renewable Energy 2020, 147, 1418–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Xiao, Weihao Hu, Di Cao, Qi Huang, Cong Chen, and Zhe Chen. “Optimized Sizing of a Standalone PV-Wind-Hydropower Station with Pumped-Storage Installation Hybrid Energy System.” Renewable Energy 2020, 147, 1418–1431. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yanfang, Miao Yang, Liang Shu, Shasha Li, and Zhiping Liu. 2020. “A Novel Parallel Assembly Sequence Planning Method for Complex Products Based on PSOBC.” Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Fu-Lan, Chou-Yuan Lee, Zne-Jung Lee, Jian-Qiong Huang, and Jih-Fu Tu. “Incorporating Particle Swarm Optimization into Improved Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm Applied to Classify Imbalanced Data.” Symmetry 2020, 12, 229. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H. , Zhu, C. , Song, C., Liu, H., & Bai, H. “Influences of Carrier Assembly Errors on the Dynamic Characteristics for Wind Turbine Gearbox.” Mechanism and Machine Theory 2016, 103, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Zh. , Zhang, J. 2008. “Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization.” Lecture Notes in Computer Science 5217. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D. , Li, R., Zheng, Y. et al. Cumulative Major Advances in Particle Swarm Optimization from 2018 to the Present: Variants, Analysis and Applications. Arch Computat Methods Eng (2025). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).