Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

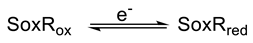

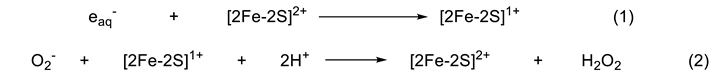

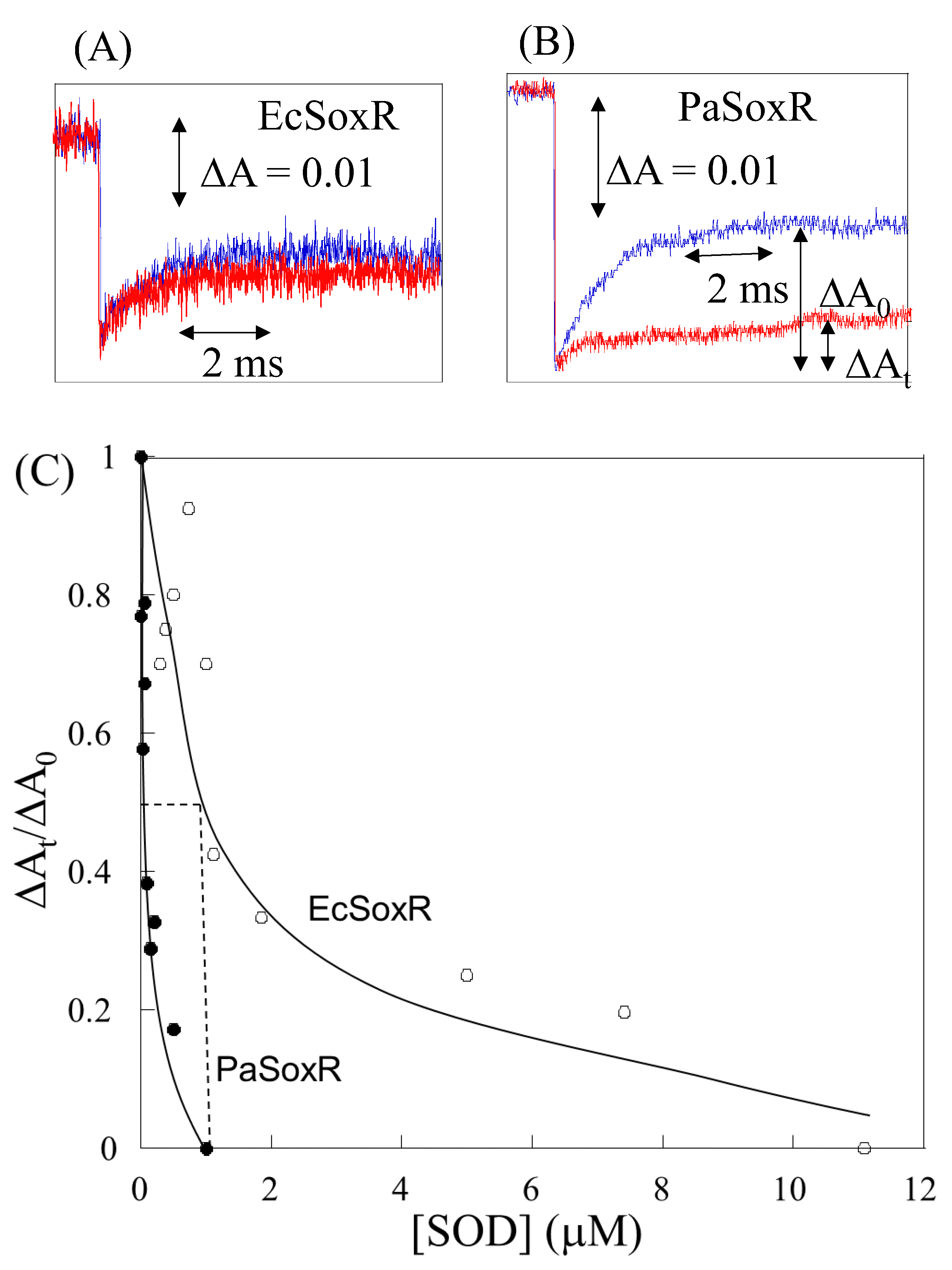

2. Direct Reaction of O2- with [2Fe-2S] Cluster in SoxR

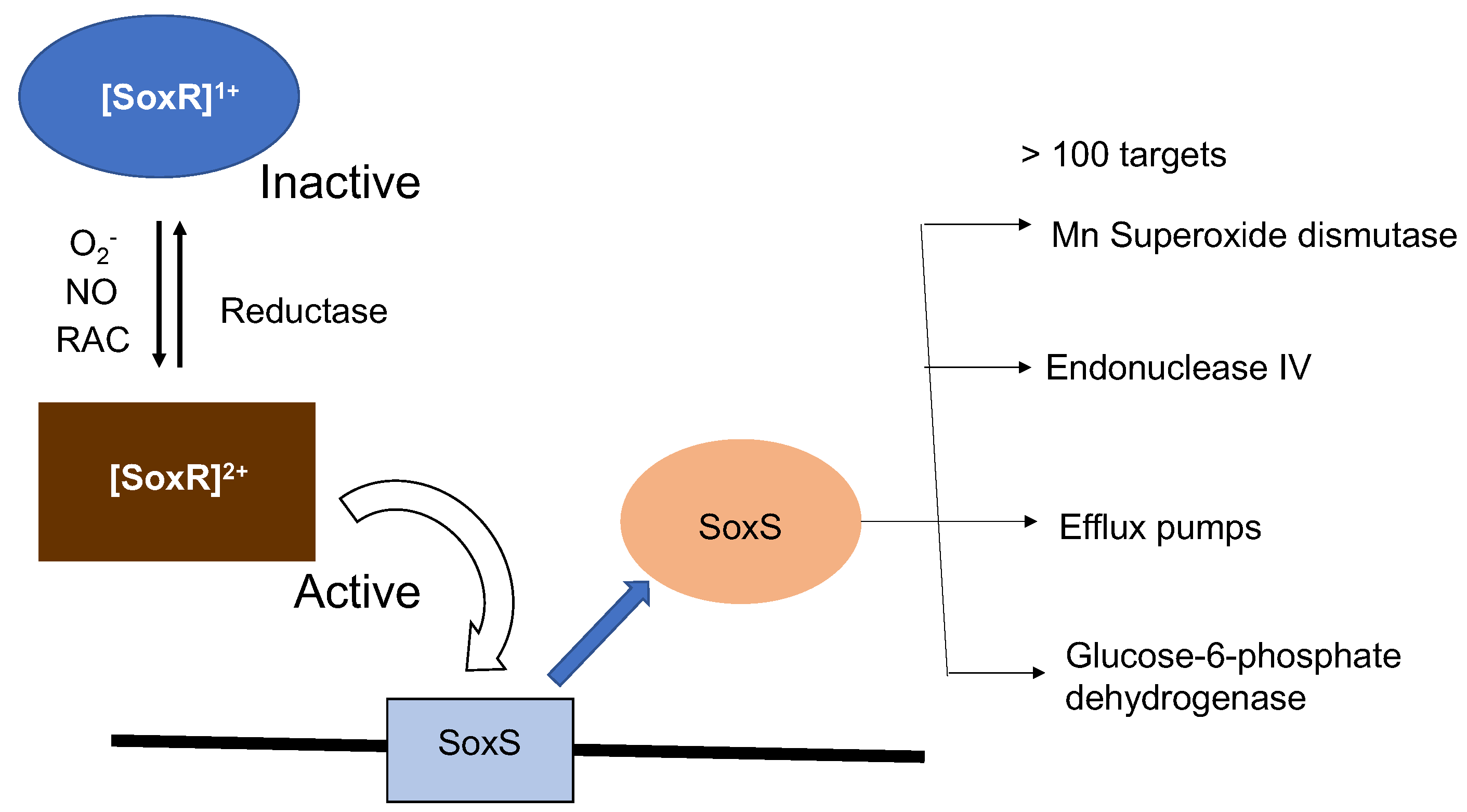

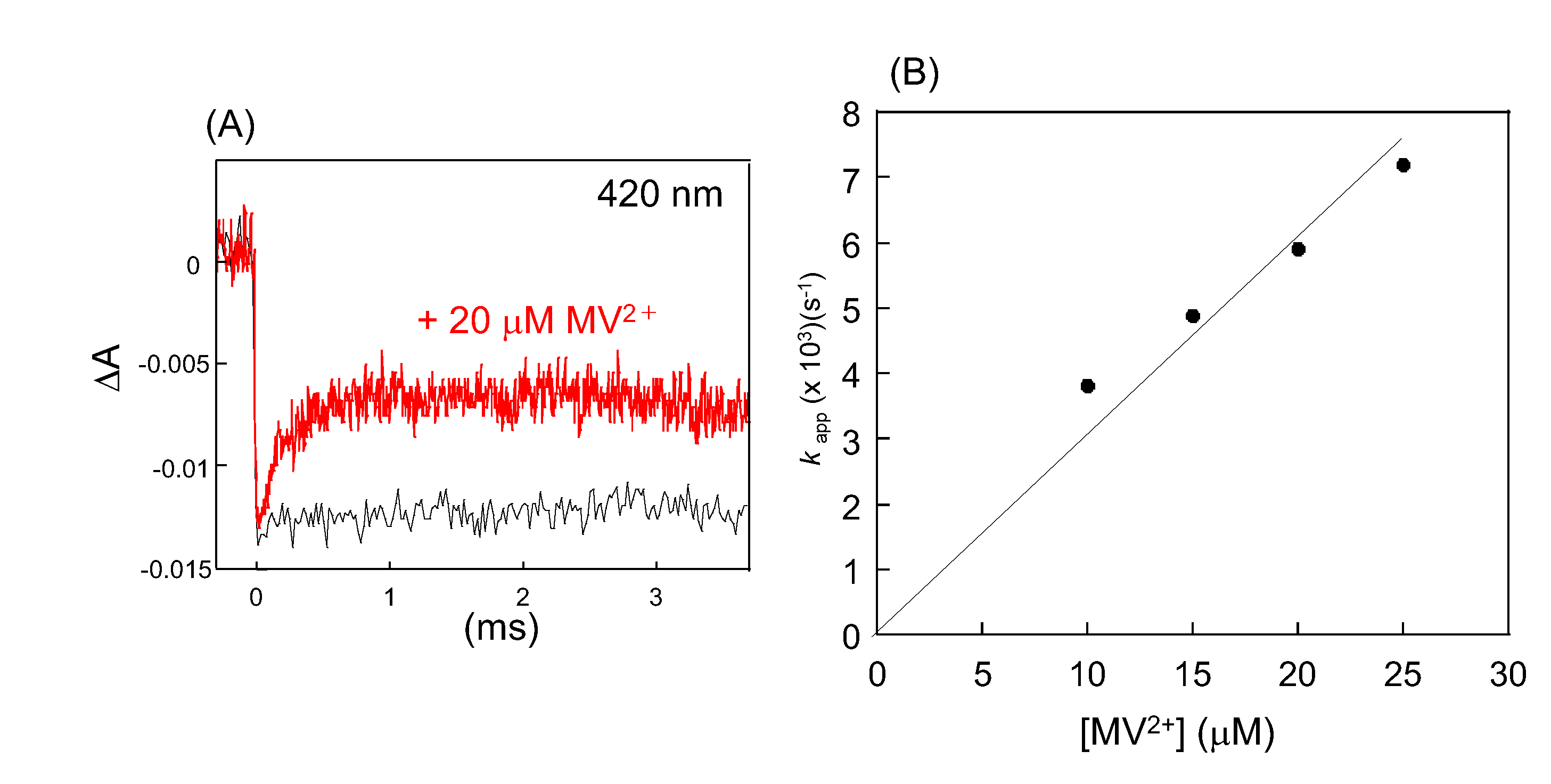

3. Response of the SoxR [2Fe-2S] Cluster to RACs

4. Physiological Significance of SoxR Response to O2- and RACs

5. Conclusion and Future Respective

References

- E. Boncella, E. T. Sabo, R. M. Santore, J. Carter, J. Whalen, J. D. Hudspeth, and C. N. Morrison, “The expanding utility of iron-sulfur clusters: Their functional roles in biology, synthetic small molecules, maquettes and artificial proteins, biomimetic materials, and therapeutic strategies” Coordination Chem. Vol. 453, 214229 2022.

- M. Gupta and C. E. Outten, “Iron-Sulfur Cluster Signaling; The Common Thread in Fungal Iron Regulation,” Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. Vol. 55, 189-201, 2020.

- J. C. Crack, J. Green, A. J. Thomson, and N. E. le Brun, “Iron-sulfur cluster sensor-regulators.” Curr. Opin. in Chem. Biol. Vol. 16, 35-44, 2012.

- H. Beinert, R. H. Holm, E. Münck, “Iron-sulfur clusters: Nature’s modular, multipurpose structures.” Science, Vol.277, 653-659, 1997.

- D. Read, R. ET. Bentrley, S. L. Archer, K. J. Dunham-Snary, “Mitochondrial iron-sulfur clusters: Structure, function, and an emerging role in vascular biology.” Redox Biology, Vol.47, 12164, 2021.

- S. M. Bian and J. A. Cowan, “Protein-bound iron-sulfur centers. Form, function, and assembly.” Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999; 190, 1049–1066.

- P. J. Kiley and H. Beinert, “The role of Fe-S proteins in sensing and regulation in bacteria,” Curr. Opin. Microbiol., Vol. 6, 181-185, 2003.

- H. Ding, B. Demple, “In vivo kinetics of a redox-regulated transcriptional switch,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Vol. 97, 5146-5150, 2000.

- F. Amábile-Cuevas, B. Demple, “Molecular characterization of the soxRS genes of Escherichia coli: Two genes control a superoxide stress regulon,” Nucleic Acids Res. Vol.19, 4479-4484, 1991.

- P. J. Pomposiello, M. H. J. Bennik, B. Demple, “Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli responses to superoxide stress and sodium salicylate.” J. Bacteriol. Vol.183, 3890-3892, 2001.

- K. Kobayashi, M. Fujikawa, and T. Kozawa, “Oxidative stress sensing by the iron-sulfur cluster in the transcription factor, SoxR” J. Inorg. Biochem, Vol.133, 87-91, 2014.

- P. Gaudu, and B. Weiss, “SoxR, a [2Fe-2S] transcription factor, is active only in its oxidized.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. Vol. 93, 10094-10098, 1996.

- M. Fujikawa, K. Kobayashi, and T. Kozawa, “Direct Oxidation of the [2Fe-2S] Cluster in SoxR Protein by Superoxide. Distinct Differential Sensitivity to Superoxide-Mediated Signal Transduction.” J. Biol. Chem. Vol. 287, 35702-35708, 2012.

- J.L. Blanchard, W. Y. Wholey, E. M. Conlon, and P. J. Pomposiello, “Rapid changes in gene expression dynamics in response to superoxide reveal soxRS-dependent and -independent transcriptional networks.” PLoS ONE Vol.2 e1186, 2007.

- L. E. P. Dietrich, T. K. Teal, A. Price-Whelan, and A. D. K. Newman, “ Redox-Active Antibiotics Control Gene Expression and Community Behavior in Divergent Bacteria.” Science Vol. 321, 1203-1206, 2008.

- R. D. Cruz, Y. Gao, S. Penumetcha, R. Sheplock, K. Weng, and M. Chander, “Expression of the Streptomyces coelicolor SoxR Regulon Is Intimately Linked with Actinorhodin Production.” J. Bactriol. Vol. 192, 6428-6438, 2010.

- J.-H. Shin, A. K. Singh, D.-J. Cheon, and J.-H. Roe, J.-H. “Activation of the SoxR Regulon in Streptomyces coelicolor by the Extracellular Form of the Pigmented Antibiotic Actinorhodin.” J. Bacteriol. Vol.193, 75-81, 2011.

- K. Singh, J.-H. Shin, K.-L. Lee, J. A. Imlay, and J.-H. Roe, “Comparative study of SoxR activation by redox-active compounds” Mol. Microbiol. Vol. 90, 983–996, 2013.

- Z. Ma, F. E. Jacobsen, and D. P. Giedroc, “Coordination Chemistry of Bacterial Metal Transport and Sensing” Chem. Rev. Vol. 109, 4644-4681, 2009.

- S. I. Liochev, “Is superoxide able to induce SoxRS ?” Free Radic. Biol. Med Vol. 2011; 50, 1813.

- L. E. P. Dietrich and P. J. Kiley “A shared mechanism of SoxR activation by redox-cycling compounds” Mol. Microbiol. Vol. 2011; 79, 1119–1122.

- M. Gu and J. A. Imaly, “The SoxRS response of Escherichia coli is directly activated by redox-cycling drugs rather than by superoxide.” Mol. Microbiol. Vol. 79, 1136-1150, 2011.

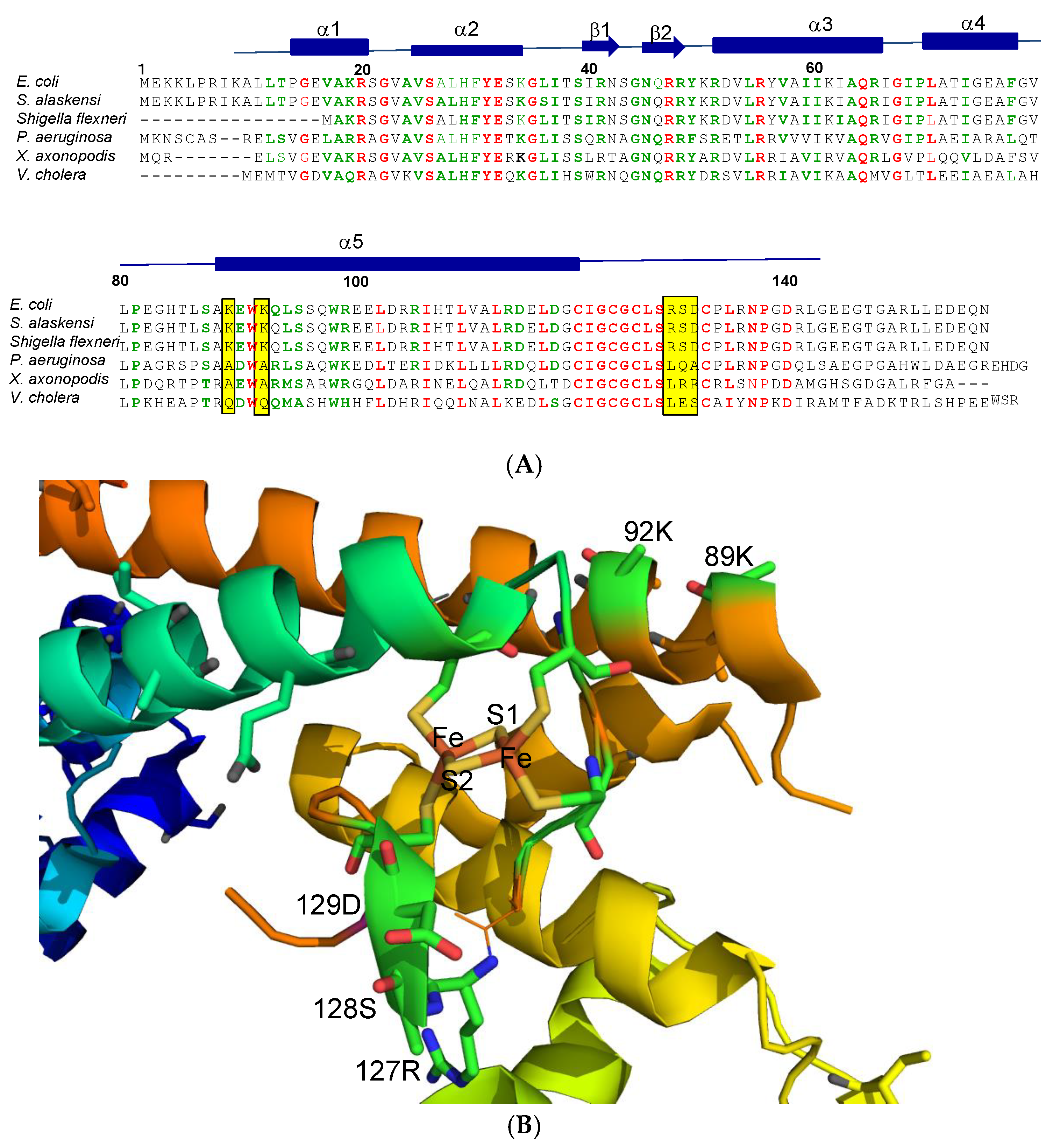

- M. Fujikawa, K. Kobayashi, Y. Tsutsui, T. Tanaka, and T. Kozawa, “Rational Tuning of Superoxide Sensitivity in SoxR, the [2Fe-2S] Transcription Factor: Implication of Species-Specific Lysine Residues.” Biochemistry Vol. 56, 403-410, 2017.

- S. Watanabe, A. Kita, K. Kobayashi, and K. Miki, “Crystal structure of the [2Fe-2S] oxidative-stress sensor SoxR bound to DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. Vol. 105, 4121-4126, 2008.

- E. D. Getzoff, J. A. Tainer, P. K.Weiner, P. A. Kollman, J. S. Richardson, and D. C. Richardson, “Electrostatic recognition between superoxide and copper, zinc superoxide dismutase.” Nature Vol. 306, 287-290, 1983.

- M. L. Ludwig, A. L. Metzger, K. A. Pattrige, and W. C. Stallings (1991) “Manganese superoxide dismutase from Thermus thermophilus: A structural model refined at 1.8 Å resolution.” J. Mol. Biol. Vol. 219, 335-358, 1991.

- Y. Sheng, I. A. Abreu, D. E. Cabelli, M. J. Maroney, A.-F. Miller, M. Teixeira, J. S.Valentine, “Superoxide Dismutases and Superoxide Reductases.” Chem. Rev. Vol. 114, 3854-3918, 2014.

- K. L. Lee, A. K. Singh, L. Heo, C. Seok, and J.-H. Roe “Factors affecting redox potential and differential sensitivity of SoxR to redox-active compounds.” Mol. Microbiol. Vol. 97, 808-821 2015.

- R. Sheplock, D. A. Recinos, N. Macknow, L. E. P. Dietrich, and M. Chander, Species-specific residues calibrate SoxR sensitivity to redox-active molecules. Mol. Microbiol. Vol. 87, 368-381. 2013.

- K. Kobayashi, T. Tanaka, T. Kozawa, “Kinetics of the Oxidation of the [2Fe-2S] Cluster in SoxR by Redox-Active Compounds as Studied by Pulse Radiolysis.” Biochemistry Vol. 64, 895-902, 2025.

- E. Steckhan, and T. Kuwana, “Spectrochemical study of mediators. I Bipyridyum salts and their electron transfer to cytochrome C.” Ber. Bunsengesellschaft Phys. Chem, Vol. 78, 253-258, 1974.

- P. Wardman, “Reduction Potentials of One-Electron Couples involving Free Radicals in Aqueous Solution.” J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data Vol. 18, 1637-1655, 1989.

- A. Moffet, J. Foley, J., and M. H. Hecht “Midpoint reduction potentials and heme binding stoichiometries of de nova proteins from designed combinatorial libraries.” Biophys. Chem. Vol. 35105, 231-239, 2003.

- F. Kuo, T. Mashino and I. Fridovich, “α,β-Dihydroxyisovalerate Dehydratase.” J. Biol. Chem. Vol. 262, 4724-4727 1987.

- P. N. Gardner and I. Fridovich, I. “Superoxide Sensitivity of the Escherichia coli Aconitase.” J. Biol. Chem. Vol. 266, 19328-19333, 1991.

- P. N. Gardner, and I. Fridovich, “Superoxide Sensitivity of the Escherichia coli 6-Phosphogluconate Dehydratase.” J. Biol. Chem. Vol. 266, 1478-1483, 1991.

- P. J. Pomposiello, and B. Demple “ReDox-operated genetic switches: the SoxR and OxyR transcription factors.” Trends Biotechnol. Vol. 19, 109-114, 2001.

- J. A. Imaly and I. Fridovich “Superoxide sensitivity of the Escherichia coli 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase” J. Biol. Chem. Vol. 266, 1478-1483, 1991.

- H. Ding, E. Hidalgo, B. Demple “ The redox stateof the [2Fe-2S] clusters in SoxR protein regulates its activity as a transcription factor” J. Biol. Chem. Vol. 271, 33173-33175, 1996.

- K. Kobayashi, and S. Tagawa “ Activation of SoxR-dependent transcription in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biochem. Vol. 136, 607-615, 2004.

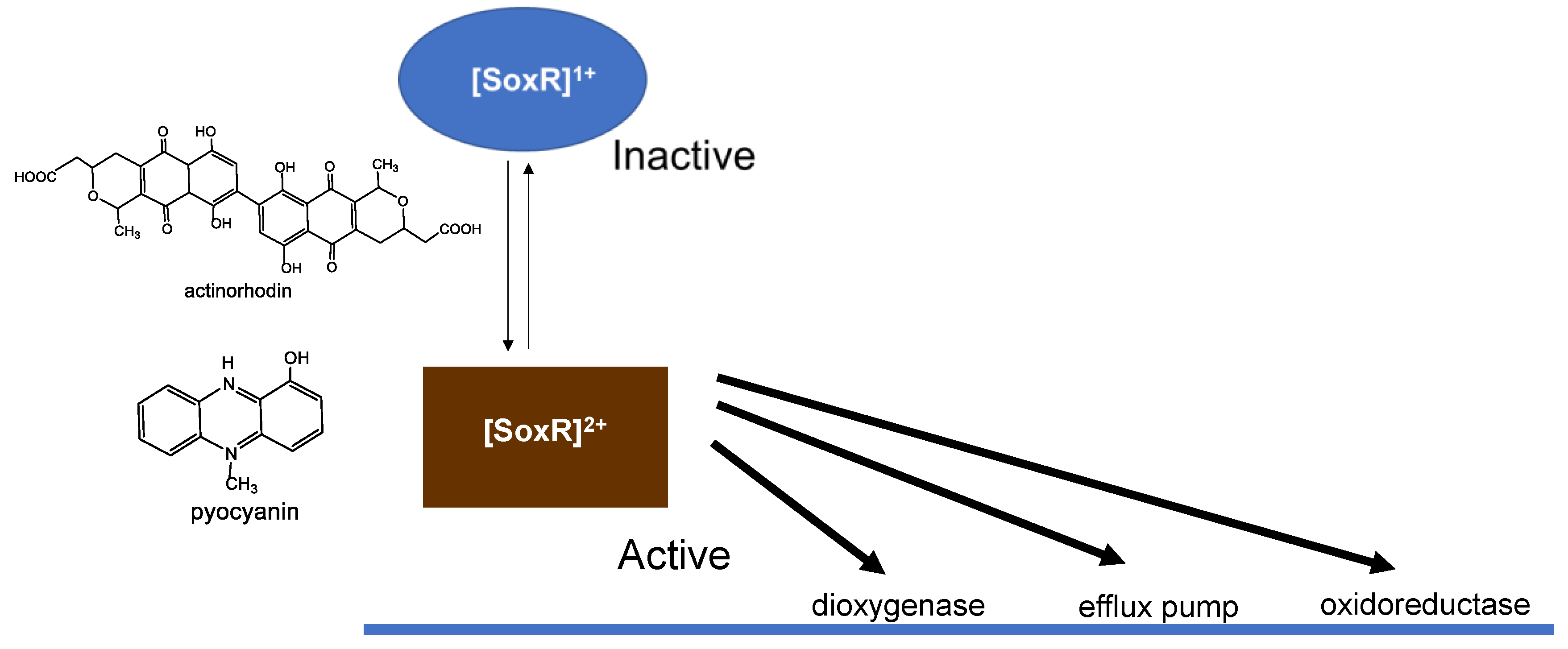

| E. coli | k × 108 (M-1 s-1) |

| WT | 5.0 |

| R127LS128QD129A | 4.8 |

| D129A | 5.0 |

| K89A | 3.8 |

| K92A | 2.2 |

| K89AK92A | 0.33 |

| K89RK92R | 4.7 |

| K89EK92E | 0.31 |

| P.aeruginosa | |

| WT | 0.4 |

| A87K | 2.1 |

| A90K | 5.4 |

| L125RQ126SA127D | 0.4 |

| RAC compounds | E0 (vs NHE) (mv) | EcSoxR k (× 108 M-1s-1) |

PaSoxR k (× 108 M-1s-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MV2+ Dq Dur Pyo PMS |

-440 31) -358 32) -260 32) -34 33) +8033) |

3.0 5.7 2.1 7.1 16.0 |

3.0 5.5 2.6 6.8 14.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).