Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.2. Iodine Analysis

2.3. Method Validation

2.4. Risk Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

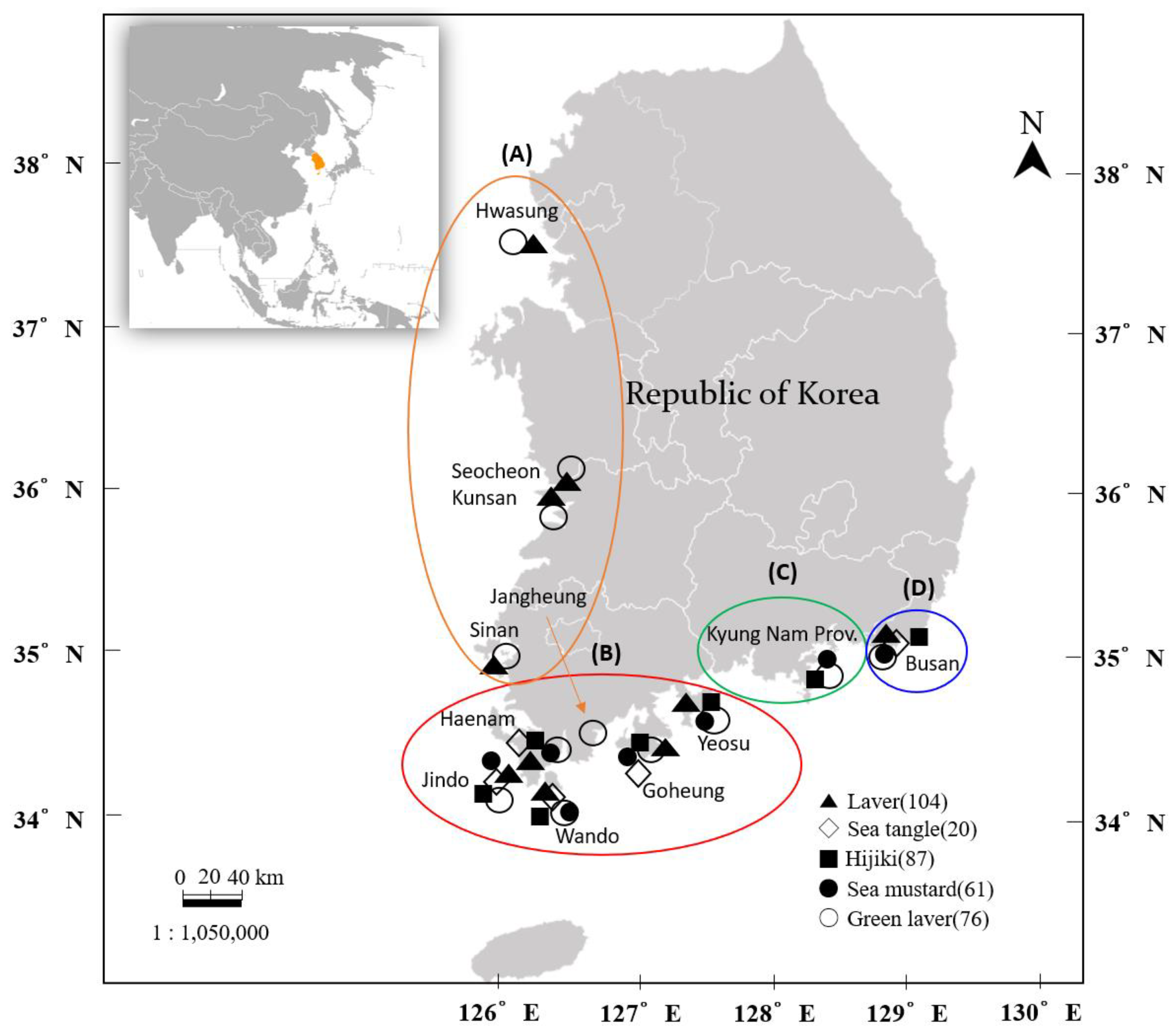

3.1. Sampling Information

3.2. Total Iodine Content of Seaweed According to Various Classification Criteria

3.2.1. Variation in Iodine Content According to Cultivation Method (Wild and Farmed)

3.2.2. Temporal Variation in Iodine Content According to Collection Year (2021–2024)

3.2.3. Geographical Variation in Iodine Content According to Collection Area

3.3. Validation Method for Iodine Content of the Five Major Seaweeds

3.4. Risk Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacArtain, P.; Gill, C.I.R.; Brooks, M.; Campbell, R.; Rowland, I.R. Nutritional value of edible seaweeds. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.L.; Potin, P.; Craigie, J.S.; Raven, J.A.; Merchant, S.S.; Helliwell, K.E.; Smith, A.G.; Camire, M.E.; Brawley, S.H. Algae as nutritional and functional food sources: revisiting our understanding. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 949–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, F.; Takenaka, S.; Katsura, H.; Masumder, S.A.; Abe, K.; Tamura, Y.; Nakano, Y. Dried green and purple lavers (nori) contain substantial amounts of biologically active vitamin B(12) but less of dietary iodine relative to other edible seaweeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 2341–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.S.; Allsopp, P.J.; Magee, P.J.; Gill, C.I.R.; Nitecki, S.; Strain, C.R.; McSorley, E.M. Seaweed and human health. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, I.P.S.; Kim, M.S.; Son, K.T.; Jeong, Y.H.; Jeon, Y.J. Antioxidant activity of marine algal polyphenolic compounds: A mechanistic approach. J. Med. Food 2016, 19, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, E.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Seaweeds as nutraceuticals for health and nutrition. Phycologia 2019, 58, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Wijesekara, I.; Li, Y.; Kim, S.K. Phlorotannins as bioactive agents from brown algae. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 2219–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Food from the ocean (Scientific Opinion No. 3/2017 Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg), 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/sam/pdf/sam_food-from-oceans_report.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- McHugh, D.J. A guide to the seaweed industry. FAO Fish. Tech. Pap.; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy 2003. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/y4765e/y4765e00.htm (accessed on 10 May 2025), 441.

- Mouritsen, O.G.; Dawczynski, C.; Duelund, L.; Jahreis, G.; Vetter, W.; Schröder, M. On the human consumption of the red seaweed dulse (Palmaria palmata (L.) Webber & Mohr). J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 1777–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, P.; O’Hara, C.; Magee, P.J.; McSorley, E.M.; Allsopp, P.J. Risks and benefits of consuming edible seaweeds. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on the safety of seaweed and iodine content. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3660–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, P.P.A. Iodine, seaweed, and the thyroid. Eur. Thyroid J. 2021, 10, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSANZ (Food Standards Australia New Zealand). Imported food risk statement. Brown seaweed of the Phaeophyceae class and iodine, 2023. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-11/Brown%20seaweed%20and%20Iodine.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Andersson, M. Update on iodine status worldwide. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2012, 19, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, S.C.; Button, S.; Rayman, M.P. Iodine concentration of organic and conventional milk: implications for iodine intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrenti, S.; Baldini, E.; Pironi, D.; Lauro, A.; D’Orazi, V.; Tartaglia, F.; Tripodi, D.; Lori, E.; Gagliardi, F.; Praticò, M.; et al. Iodine: its role in thyroid hormone biosynthesis and beyond. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Eom, J.S.; Jo, S.U.; Guan, L.L.; Park, T.S.; Seo, J.K.; Lee, Y.K.; Bae, D.R.; et al. Red seaweed extracts reduce methane production by altering rumen fermentation and microbial composition in vitro. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 985824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Yeoh, Y.J.; Seo, M.J.; Lee, G.H.; Kim, C.I. Estimation of dietary iodine intake of Koreans through a total diet study (TDS). Korean J. Community Nutr. 2021, 26, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoF (Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries). South Korea, 2018. Available online: https://www.mof.go.kr/doc/ko/selectDoc.do?docSeq=20773&menuSeq=929&bbsSeq=27 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- MFDS (Ministry of Food and Drug Safety). South Korea. Common Guidelines for Risk Assessment of Human Applications, 2019. Available online: https://www.mfds.go.kr (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Kim, M.H.; Cho, M.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Jo, M.R.; Moon, Y.S.; Im, M.H. Monitoring and risk assessment of pesticide residues in fishery products using GC-MS/MS in South Korea. Toxics 12, 299. [CrossRef]

- Rehder, D. Vanadate-dependent peroxidase in macroalgae: function, applications, and environmental impact. J. Oceanogr. Mar. Sci. 2014, 2, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Conklin, S.D.; Redan, B.W.; Ho, K.K.H.Y. Determination of the nutrient and toxic element content of wild-collected and cultivated seaweeds from Hawaii. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 4, 595–605. [CrossRef]

- Schiener, P.; Black, K.D.; Stanley, M.S.; Green, D.H. The seasonal variation in the chemical composition of the kelp species Laminaria digitata, Laminaria hyperborea, Saccharina latissimi and Alaria esculenta. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 27, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roleda, M.Y.; Skjermo, J.; Marfaing, H.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Rebours, C.; Gietl, A.; Stengel, D.B.; Nitschke, U. Iodine content in bulk biomass of wild-harvested and cultivated edible seaweeds: inherent variations determine species-specific daily allowable consumption. Food Chem. 2018, 254, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüning, K. Seaweeds: Their Environment, Biogeography, and Ecophysiology; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- Gunnarsdóttir, I.; Brantsæter, A.L. Iodine: a scoping review for Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67, 10369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sæther, M.; Diehl, N.; Monteiro, C.; Li, H.; Niedzwiedz, S.; Burgunter-Delamare, B.; Scheschonk, L.; Bischof, K.; Forbord, S. The sugar kelp Saccharina latissima II: Recent advances in farming and applications. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 1953–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakre, I.; Solli, D.D.; Markhus, M.W.; Mæhre, H.K.; Dahl, L.; Henjum, S.; Alexander, J.; Korneliussen, P.-A.; Madsen, L.; Kjellevold, M. Commercially available kelp and seaweed products—valuable iodine source or risk of excess intake? Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 65, 7584–7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küpper, F.C.; Carpenter, L.J.; McFiggans, G.B.; Palmer, C.J.; Waite, T.J.; Boneberg, E.M.; Woitsch, S.; Weiller, M.; Abela, R.; Grolimund, D.; et al. Iodine accumulation provides kelp with an inorganic antioxidant impacting atmospheric chemistry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 6954–6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, J.; Pino, S.; Critchley, A.; Braverman, L.E. Variability of iodine content in common commercially available edible seaweeds. Thyroid 2004, 14, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinovic, J.; Rodrigues, C.; Diniz, M.; Noronha, J.P. Determination of total iodine content in edible seaweeds: application of inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectroscopy. Algal Res. 2021, 53, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakre, I.; Tveit, I.B.; Myrmel, L.S.; Fjære, E.; Ballance, S.; Rosendal-Riise, H. Bioavailability of iodine from a meal consisting of sushi and a wakame seaweed salad—A Randomized Crossover Trial. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 7707–7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Paz, S.; Rubio, C.; Gutiérrez, Á.J.; Hardisson, A. Human exposure to iodine from the consumption of edible seaweeds. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 197, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Chen, L.; Wallace, T.; Lee, H.J. The association between iodine intake and thyroid disease in iodine-replete regions: the Korean genome and epidemiology study. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2025, 19, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.O.; Kwon, K.I.; Lee, M.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, C.I. Iodine intake from brown seaweed and the related nutritional risk assessment in Koreans. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2024, 18, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANSES (French agency for food, environmental and occupational health and safety). Annu. Rep. 2018.

- Method. AOAC Intl. 20th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Communities Official Method of Analysis (OMA) 2016, 2012. Rockville, MD, USA.

| KN | BS | JN | Others | Total | |||||

| GH | YS | WD | JD | HN | |||||

| Laver | 0 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 35 | 26 | 19 | 104 |

| Sea tangle | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 20 |

| Sea mustard | 2 | 8 | 15 | 2 | 22 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 61 |

| Hijiki | 1 | 3 | 21 | 6 | 35 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 87 |

| Green laver | 2 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 30 | 13 | 15 | 3 | 76 |

| Total | 5 | 23 | 56 | 11 | 104 | 72 | 55 | 22 | 348 |

| Species | Growth method | Harvest year | Sampling region | |||||||||||

| Wild | Farmed | 2020-21 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | KN | BS | JN | Others | |||||

| GH | YS | WD | JD | HN | ||||||||||

| Laver | 3.92 | 6.67 | 4.48 | 4.85 | 5.41 | 7.95 | a- | 3.96 | 5.88 | 1.81 | 4.87 | 7.21 | 6.70 | 4.85 |

|

Sea tangle |

219 | 264 | 235 | 254 | 140 | 229 | a - | 268 | 83 | a - | 241 | 335 | 215 | a - |

| Sea mustard | 11.0 | 15.9 | 10.72 | 10.8 | 16.2 | 12.4 | 16.7 | 17.8 | 12.1 | 12.9 | 10.6 | 14.5 | 13.5 | a - |

| Hijiki | 58.1 | 64.2 | 72.2 | 51.3 | 67.1 | a - | 77.3 | 98.4 | 52.5 | 50.5 | 67.2 | 49.5 | 80.0 | a - |

| Green laver | 5.54 | 7.04 | 5.41 | 5.57 | 6.50 | 19.5 | 6.23 | 9.84 | 5.75 | 9.43 | 6.58 | 4.98 | 5.06 | 3.92 |

|

CRM (SRM 3232) |

LODa | LOQb | Linearity | Recovery |

| (µg/kg) | (µg/kg) | (R2) | (%) | |

| 0.92 | 2.75 | 0.9996 | 87.44±2.74 |

| Species |

ACDI (mg/kg dw) |

SC (g/day)a |

EDI 1 (µg/day/person)d |

EDI 2 (µg/kg bw/day)e |

Scenario 1f | Scenario 2g | |||||||||

| HI | HI | ||||||||||||||

| Avg.b | Act.c | Avg. | Act. | Avg. | Act. | Avg. | Act. | Avg. | Act. | ||||||

| Laver | 100.2 | 1.02 | 2.94 | 102.44 | 294.69 | 1.69 | 4.85 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.29 | ||||

| Sea tangle | 2432.1 | 0.67 | 15.79 | 1632.61 | 38393.31 | 26.88 | 632.01 | 0.68 | 16.00 | 1.58 | 37.18 | ||||

| Sea mustard | 176.9 | 0.72 | 4.83 | 127.12 | 854.19 | 2.09 | 14.06 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.12 | 0.83 | ||||

| Hijiki | 526.6 | 0.09 | 18.30 | 47.50 | 9636.62 | 0.78 | 158.63 | 0.02 | 4.02 | 0.05 | 9.33 | ||||

| Green laver | 86.1 | 0.38 | 24.39 | 32.86 | 2100.32 | 0.54 | 34.57 | 0.01 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 2.03 | ||||

| Total | 0.81 | 21.37 | 1.88 | 49.31 | |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).