Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

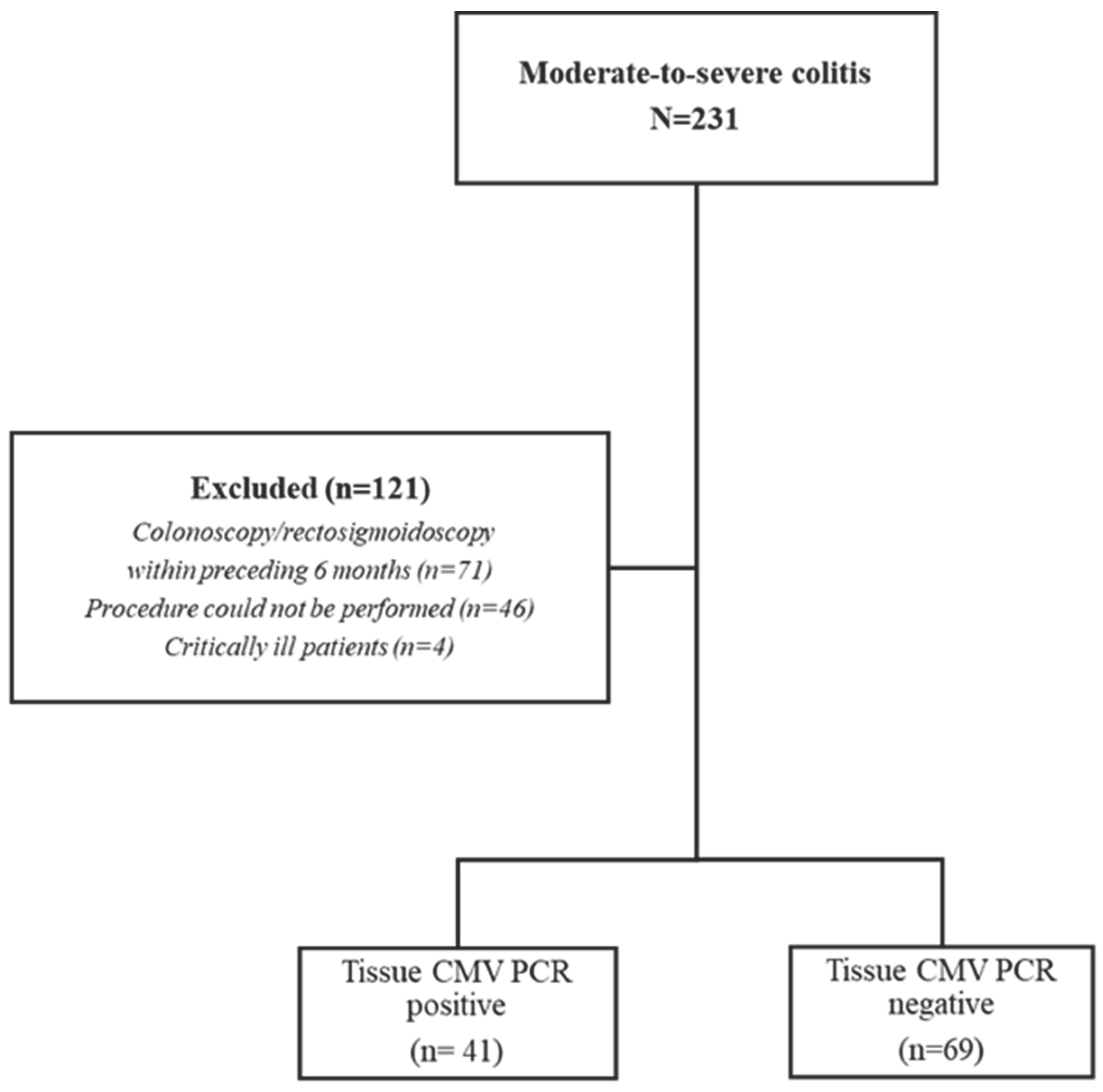

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Endoscopic Procedures and Tissue Sampling

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest and funding statement

Ethical statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Yeh, P.-J.; Wu, R.-C.; Chen, C.-L.; Chiu, C.-T.; Lai, M.-W.; Chen, C.-C.; Chiu, C.-H.; Pan, Y.-B.; Lin, W.-R.; Le, P.-H. Cytomegalovirus diseases of the gastrointestinal tract in immunocompetent patients: A narrative review. Viruses 2024, 16, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domènech, E.; Vega, R.; Ojanguren, I.; Hernández, Á.; Garcia-Planella, E.; Bernal, I.; Rosinach, M.; Boix, J.; Cabré, E.; Gassull, M.A. Cytomegalovirus infection in ulcerative colitis: a prospective, comparative study on prevalence and diagnostic strategy. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2008, 14, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourad, F.H.; Hashash, J.G.; Kariyawasam, V.C.; Leong, R.W. Ulcerative colitis and cytomegalovirus infection: from A to Z. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2020, 14, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, P.-J.; Wu, R.-C.; Chiu, C.-T.; Lai, M.-W.; Chen, C.-M.; Pan, Y.-B.; Su, M.-Y.; Kuo, C.-J.; Lin, W.-R.; Le, P.-H. Cytomegalovirus diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Viruses 2022, 14, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, K.; Alam, S.; Bond, A.; Chinnappan, L.; Probert, C. cytomegalovirus and inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2015, 41, 725–733. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir, B.; Atay, A.; Kayhan, M.A.; Ozin, Y.O.; Gokce, D.T.; Altunsoy, A.; Guner, R. Tissue quantitative RT–PCR test for diagnostic significance of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and treatment response: Cytomegalovirus infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Medicine 2023, 102, e34463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, G.; Moss, A.C. Cytomegalovirus in inflammatory bowel disease: pathogen or innocent bystander? Inflammatory bowel diseases 2010, 16, 1620–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentzer, A.; Veyrard, P.; Roblin, X.; Saint-Sardos, P.; Rochereau, N.; Paul, S.; Bourlet, T.; Pozzetto, B.; Pillet, S. Cytomegalovirus and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) with a special focus on the link with ulcerative colitis (UC). Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, S.; Saglik, I.; Dolar, E.; Cesur, S.; Ugras, N.; Agca, H.; Merdan, O.; Ener, B. Diagnostic utility of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA quantitation in ulcerative colitis. Viruses 2024, 16, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Yamakawa, T.; Hirano, T.; Kazama, T.; Hirayama, D.; Wagatsuma, K.; Nakase, H. Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to cytomegalovirus infections in ulcerative colitis patients based on clinical and basic research data. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazır-Konya, H.; Avkan-Oğuz, V.; Akpınar, H.; Sağol, Ö.; Sayıner, A. Investigation of cytomegalovirus in intestinal tissue in a country with high CMV seroprevalence. The Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology 2021, 32, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, F.; Gionchetti, P.; Eliakim, R.; Ardizzone, S.; Armuzzi, A.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Burisch, J.; Gecse, K.B.; Hart, A.L.; Hindryckx, P. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2017, 11, 649–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, A.; Ford, A.C. Poor correlation between patient-reported and endoscopic components of the Mayo score in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachmilewitz, D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. British Medical Journal 1989, 298, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeya, K.; Hanai, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Osawa, S.; Kawasaki, S.; Iida, T.; Maruyama, Y.; Watanabe, F. The ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity more accurately reflects clinical outcomes and long-term prognosis than the Mayo endoscopic score. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2016, 10, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoepfer, A.M.; Beglinger, C.; Straumann, A.; Trummler, M.; Renzulli, P.; Seibold, F. Ulcerative colitis: correlation of the Rachmilewitz endoscopic activity index with fecal calprotectin, clinical activity, C-reactive protein, and blood leukocytes. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2009, 15, 1851–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Yaari, S.; Stoff, R.; Caplan, O.; Wolf, D.G.; Israeli, E. Diagnosis of cytomegalovirus infection during exacerbation of ulcerative colitis. Digestion 2017, 96, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, J.-M.; Kwak, M.S.; Hwang, S.W. Risk factors and clinical outcomes associated with cytomegalovirus colitis in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2016, 22, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.C.; Jeen, Y.M.; Jeen, Y.T. Approach to cytomegalovirus infections in patients with ulcerative colitis. The Korean journal of internal medicine 2017, 32, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillet, S.; Roblin, X.; Cornillon, J.; Mariat, C.; Pozzetto, B. Quantification of cytomegalovirus viral load. Expert review of anti-infective therapy 2014, 12, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römkens, T.E.; Bulte, G.J.; Nissen, L.H.; Drenth, J.P. Cytomegalovirus in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. World journal of gastroenterology 2016, 22, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Pan, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. Epstein–Barr virus and human cytomegalovirus infection in intestinal mucosa of Chinese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 915453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Yong, C.; Wang, Y.; Wei, H.; Zhao, K.; He, B.; Cui, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Cytomegalovirus Pneumonia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Literature Review and Clinical Recommendations. Infection and Drug Resistance 2023, 6195–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandiel, A.; Lashner, B. Cytomegalovirus colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2006, 101, 2857–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Ji, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liu, X.; Li, W. Cytomegalovirus infection and steroid-refractory inflammatory bowel disease: possible relationship from an updated meta-analysis. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971-) 2018, 187, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Medina, F.; Romero-Calvo, I.; Mascaraque, C.; Martínez-Augustin, O. Intestinal inflammation and mucosal barrier function. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2014, 20, 2394–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, A.; Herrero-Fernandez, B.; Gomez-Bris, R.; Sánchez-Martinez, H.; Gonzalez-Granado, J.M. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease: innate immune system. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altunal, L.; Ozel, A.; Ak, C. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in ulcerative colitis patients: Early indicators. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 2023, 26, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Najarian, K.; Gryak, J.; Bishu, S.; Rice, M.D.; Waljee, A.K.; Wilkins, H.J.; Stidham, R.W. Fully automated endoscopic disease activity assessment in ulcerative colitis. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2021, 93, 728–736. e721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Sandborn, W.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; Bemelman, W.; Bryant, R.V.; D'Haens, G.; Dotan, I.; Dubinsky, M.; Feagan, B. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2015, 110, 1324–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhou, W.; Lv, H.; Wu, D.; Feng, Y.; Shu, H.; Jin, M.; Hu, L.; Wang, Q.; Wu, D. The association between CMV viremia or endoscopic features and histopathological characteristics of CMV colitis in patients with underlying ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2017, 23, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, Y.; Ando, T.; Hirooka, Y.; Watanabe, O.; Miyahara, R.; Nakamura, M.; Yamamura, T.; Goto, H. Characteristic endoscopic findings and risk factors for cytomegalovirus-associated colitis in patients with active ulcerative colitis. World journal of gastrointestinal endoscopy 2016, 8, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, A.C.; Guler, E.; Tirumani, S.H.; Dumot, J.; Ramaiya, N.H. Clinical, imaging, endoscopic findings, and management of patients with CMV colitis: a single-institute experience. Emergency radiology 2020, 27, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kato, J.; Kuriyama, M.; Hiraoka, S.; Kuwaki, K.; Yamamoto, K. Specific endoscopic features of ulcerative colitis complicated by cytomegalovirus infection. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG 2010, 16, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, G.S.; Raza, M.; Hale, M.F.; Lobo, A.J. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of mucosal cytomegalovirus infection in patients with acute ulcerative colitis. Annals of gastroenterology 2018, 32, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erürker Öztürk, T.; KIYICI, M.; Gülten, M.; DOLAR, M.; Gürel, S.; NAK, S.; Eren, F. Importance of using tissue PCR to diagnose CMV colitis in ulcerative colitis. Dicle Tıp Dergisi 2023, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, A.; Mishra, S.; Singh, A.K.; Sekar, A.; Sharma, V. Cytomegalovirus in ulcerative colitis: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and treatment. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2022, 16, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modified Mayo Score | ||||

| Score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Stool frequency | Normal |

1-2 more than normal | 3-4 more than normal | 4-5 more than normal |

| Rectal bleed | No bleed |

Streaks of blood with stool less than half the time | Obvious blood most of the time | Blood alone |

| Endoscopic findings | Normal | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Physician Global Assessment | Normal | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Rachmilewitz Endoscopic Activity Index | ||||

| Score | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| Granulation scattering reflected light | No | Yes | ||

| Vascular appereance | Normal | Faded/disturbed | Completely absent | |

| Fragility of mucosa | None | Contact bleeding | Spontaneous bleeding | |

| Mucosal damage (mucus, fibrin, exudate, erosion, ulcer) | None | Slight | Pronounced | |

| CMV positive UC (n=41) |

CMV negative UC (n=69) |

p value | |

| Age (year) | 45.6±19.9 | 45.9±117.53.9 | 0.93 |

|

Female, n (%) Male, n (%) |

21 (42%) 20 (58%) |

21 (31%) 48 (69%) |

0.001* 0.8 |

| Diagnosis age | 40.9±19.8 | 37.6±17.9 | 0.38 |

| Follow up time (weeks) | 59.4±60.7 | 88±72.2 | 0.02 |

| WBC | 10.1±10.8 | 9.6±4.2 | 0.8 |

| CRP | 39.9±44.6 | 33.8±51 | 0.5 |

| ESR (sedim) | 54.3±28.9 | 42.8±28.3 | 0.04 |

| Daily defecation | 10.1±6 | 9.5±7.1 | 0.6 |

| CMV PCR serum | 878.9±2473 | 71.4±316.6 | 0.008 |

|

Rachmilewitz EAI |

8.6±2.6 | 7.4±3.1 |

0.03 |

|

Mayo Score |

8.7±2.4 |

7.6±3.5 |

0.02 |

| Correlation | r | p |

| WBC | -0.16 | 0.09 |

| Daily defecation | 0.1 | 0.29 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.8 |

| Diagnosis age | 0.1 | 0.27 |

| CRP | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| Sedim | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| CMV PCR serum | 0.37 | 0.0001 |

| Mayo Score | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| Rachmilewitz Endoscopic Activity Index | 0.25 | 0.008 |

| B | Wald | p | Exp(B) | 95% C.I.for EXP(B) | |||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Results | Mayo Score | -0.15 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.85 | 0.55 | 1.31 |

| Rachmilewitz | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 1.2 | 0.75 | 1.91 | |

| Anti TNF usage | -0.7 | 0.34 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 5.18 | |

| Steroid usage in last 3 months | 2.5 | 4.73 | 0.03 | 12.1 | 1.2 | 116.03 | |

| CRP | -.003 | 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.01 | |

| Sedim | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.05 | |

| Constant | -4.7 | 4.63 | 0.03 | 0.009 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).