1. Introduction

Infertility is a disorder of the male or female reproductive system characterized by the inability to achieve pregnancy after at least 12 months of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse. This can be attributed to male factors or female factors or may remain unexplained. Some causes of infertility are preventable. Its treatment often involves in vitro fertilization (IVF) and other assisted reproductive technologies (ART) [

1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines infertility as a disorder of the reproductive system characterized by the inability to achieve pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse. This condition can be attributed to female, male, or unexplained factors.

In men, fertility primarily relies on a complex biological process; spermatogenesis. This mechanism takes place in the testes and ensures the continuous and differentiated production of spermatozoa from immature germ cells. Spermatogenesis plays a crucial role in male reproductive capacity because it is regulated by hormonal factors and influenced by genetic and environmental conditions. Any disruption of this process can lead to quantitative or qualitative alterations in spermatozoa, resulting in infertility [

2].

Male infertility can be classified into nonidiopathic and idiopathic infertility. The nonidiopathic form includes clearly identifiable causes and can be subdivided into obstructive and nonobstructive infertility. Obstructive infertility results from a blockage preventing the transport of spermatozoa despite normal testicular production. This obstruction can be congenital, such as bilateral absence of the vas deferens associated with CFTR gene mutations cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (), or acquired due to infections, trauma, or surgical procedures such as vasectomy [

3,

4].

Nonobstructive infertility is caused by impaired sperm production, whether due to genetic, hormonal, or environmental factors. Chromosomal abnormalities such as Klinefelter syndrome or Y chromosome microdeletions, hormonal imbalances affecting the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒testicular axis, or testicular damage resulting from infections, medical treatments, or environmental toxins can compromise spermatogenesis, leading to azoospermia or severe oligospermia. External factors such as oxidative stress, smoking, exposure to pollutants, and an unbalanced diet can also disrupt this process and reduce sperm quality [

4].

Finally, idiopathic infertility refers to cases where no precise cause can be identified despite thorough analyses. It is often linked to complex molecular mechanisms, unknown environmental factors, or oxidative stress, altering spermatogenesis. This form presents a diagnostic and clinical challenge, requiring more advanced investigations and tailored management, including lifestyle adjustments and the use of assisted reproductive technology.

One of the major factors contributing to male infertility, whether idiopathic or nonidiopathic, is oxidative stress, an imbalance between the production of free radicals and the capacity of the antioxidant system to neutralize them. This imbalance leads to excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are generated primarily by immature spermatozoa and leukocytes present in the ejaculate. Although low ROS production is essential for normal sperm functions, such as capacitation and acrosomal reactions, excess ROS production is harmful. The uncontrolled oxidation of membrane lipids leads to alterations in the structure and function of spermatozoa, thereby reducing their motility and fertilization ability. Moreover, ROS directly damage sperm DNA, causing strand breaks and compromising the genetic integrity of gametes. The activation of lipid peroxidation processes also induces the accumulation of toxic products, such as malondialdehyde (MDA), which exacerbates spermatogenic and testicular alterations. This phenomenon is commonly observed in patients with metabolic comorbidities, such as endocrine disorders or dyslipidemia, and affects the function of Leydig cells and hormone synthesis. Thus, analyzing the pro-/antioxidant system in seminal fluid and serum from infertile men could provide valuable insights into the involvement of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of infertility and open the door to therapeutic approaches aimed at restoring the cellular redox balance [

5].

Sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) tests and sperm chromatin condensation (SCC) tests play crucial roles in assessing the quality of sperm genetic material and understanding the underlying causes of male infertility. The SDF test measures the extent of DNA fragmentation in spermatozoa. High levels of DNA fragmentation can affect the ability of sperm to fertilize an oocyte, impair embryonic development, and increase the risk of miscarriage. On the other hand, the SCD test focuses on sperm maturation by identifying potential ruptures in the interstrand disulfide bonds of protamines (P2), leading to DNA decondensation. Tests such as the aniline blue staining technique for SCD and the TUNEL method for SDF provide a detailed evaluation of sperm genetic quality. These tests are particularly relevant for men with idiopathic infertility, as sperm DNA alterations may result from oxidative stress or cellular dysfunction. While reference and first-line tests, such as spermograms and spermocytograms, continue to guide the diagnosis and management of male infertility, the integration of these more advanced analyses into initial infertility diagnosis remains a subject of debate, although they could offer valuable insights for therapeutic management and the planning of assisted reproductive treatments [

6].

The objective of this study was to examine the relationships between sperm DNA fragmentation, sperm chromatin decondensation, and common sperm parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

Samples

This study was conducted on a population of 80 men of reproductive age who visited the reproductive biology laboratory (LABOMAC) between January 2024 and May 2024 to undergo sperm analysis tests for management as part of the exploration of couple infertility or an attempt at assisted reproductive technology through intrauterine insemination (IUI), in vitro fertilization (IVF), or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

The sperm samples were collected by masturbation after a period of sexual abstinence of 3 to 7 days in sterile containers, accompanied by a patient information sheet, in compliance with the necessary rules for aseptic sperm collection.

Basic Sample Treatment

After sample collection, the samples were placed in an incubator at 35°C for a liquefaction period of at least 15 minutes before any sperm processing. Then, conventional sperm parameters were measured via sperm analysis.

Sperm Parameter Analysis

Sperm Analysis

The sperm analysis is used to quantify pH, volume (in mL), sperm concentration (in millions/mL), total sperm count (in millions/ejaculate), and sperm viability (in %), and to qualify motility (a; b; c). The analyzed sperm parameters include appearance, which is normally whitish or yellowish in the case of infection and/or suggestive of hematospermia in the case of the presence of red blood cells in the sperm [

7].

The pH was measured after 30 minutes using a pH paper strip to avoid alkalinization, which increased over time. The volume was measured using a graduated tube. To assess motility, 10 μL of sperm were taken after homogenization and observed between a slide and coverslip under a microscope at 40x magnification, followed by a calculation of the percentage of each motility category (

Table A1) [

7].

Vitality is evaluated by mixing the sperm with eosin or nigrosin and observing them under a microscope at 40x magnification, where dead spermatozoa are stained red‒pink, whereas live spermatozoa remain colorless. The concentration is determined by placing a drop of diluted sperm on a Malassez cell and counting it according to the formula N = (n) × the dilution factor × (y) × 1000, where N is the sperm concentration, n is the number of sperm counted, and y is the number of squares counted (total 100) [

7]. The thresholds for the different sperm analysis parameters were established according to WHO standards (

Table A2).

Assessment of Sperm Morphology

The measurement of conventional sperm parameters via spermocytogram consists of the cytological examination of human spermatozoa, including the morphological analysis of abnormalities, the teratozoospermia index (TZI), and particularly the percentage of typical forms (FTs).

After homogenization of the sperm, a sperm smear is made and fixed with 1% ethanol. The slides were first immersed in hematoxylin for 1 to 3 minutes and then rinsed with water. The sample was then immersed in Shorr for 1--3 minutes, rinsed again with water, and finally dried on a heating plate to prepare for reading.

The smear is read under an optical microscope after immersion oil is added, with a magnification of 100x, or a computer-assisted sperm analysis system (CASA) is used to determine the various abnormalities of the spermatozoa.

For result analysis, the modified David classification is used to assess the presence or absence of abnormalities in different parts of the spermatozoa [

8]. The TZI percentage, which represents the average number of abnormalities per abnormal spermatozoon, is calculated on the basis of the values of the various spermocytogram parameters. Its theoretical maximum value is 4, and the typical forms correspond to Kruger’s criteria [

9]. For the evaluation of sperm morphology, a normal threshold of FT equal to 4% was used [

7] [

8] [

9].

Analysis of the Quality of the Genetic Material in Spermatozoa

The analysis of sperm quality alterations in this study focused on damage at the sperm nucleus level, which can be chromatin-related or DNA-related, in the context of male infertility.

Index of SDF by the TUNEL Technique

The protocol for the TUNEL technique includes several sample preparation steps. First, fixation and permeabilization are performed by mixing the sperm with a modified PBS solution, followed by centrifugation and collection of the pellet. A drop of this pellet is used to prepare a smear, which is then dried on a heating plate at 36°C. Next, a fixation solution (37°C formaldehyde + PBS) was added, and the slides were left at room temperature for 30 minutes. After the samples were rinsed with PBS, drops of permeabilization solution (Triton X + citrate + distilled water) were added, and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 minute. The slides were then rinsed again with a PBS solution and left to dry.

The labeling solution containing the TUNEL reaction mixture (In Situ Cell Death Detection Fluorescein, Roche®) was then applied to the smears. The slides were covered and placed in a dark box, followed by incubation at 37°C for 45 minutes. After rinsing with a modified PBS solution, drops of glycerol were added between the slides and coverslips (all steps were carried out in the dark).

Index of SCC by Aniline Blue Staining

The protocol includes the following steps: fixation and permeabilization of the spermatozoa, using the same protocol as for sperm DNA fragmentation. Then, aniline blue staining was performed by applying 1 ml of stain to the smear for 15 minutes at room temperature, followed by rinsing the slides with tap water and drying.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted via GraphPad Prism 8. Data normality was assessed with the Shapiro‒Wilk test. Group comparisons were evaluated via one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test when significant differences were observed. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sperm Parameter Analysis: Spermogram and Spermocytogram

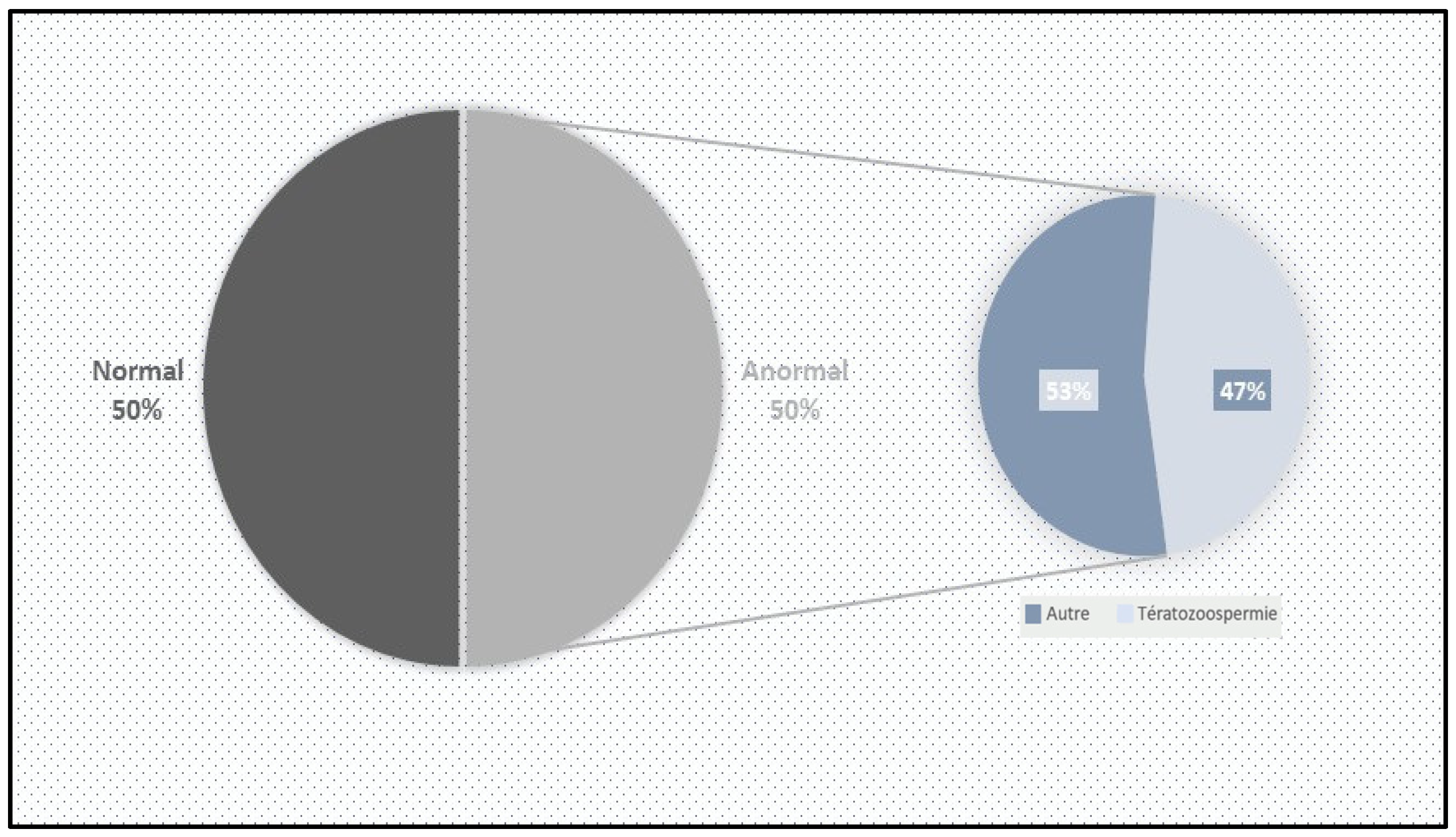

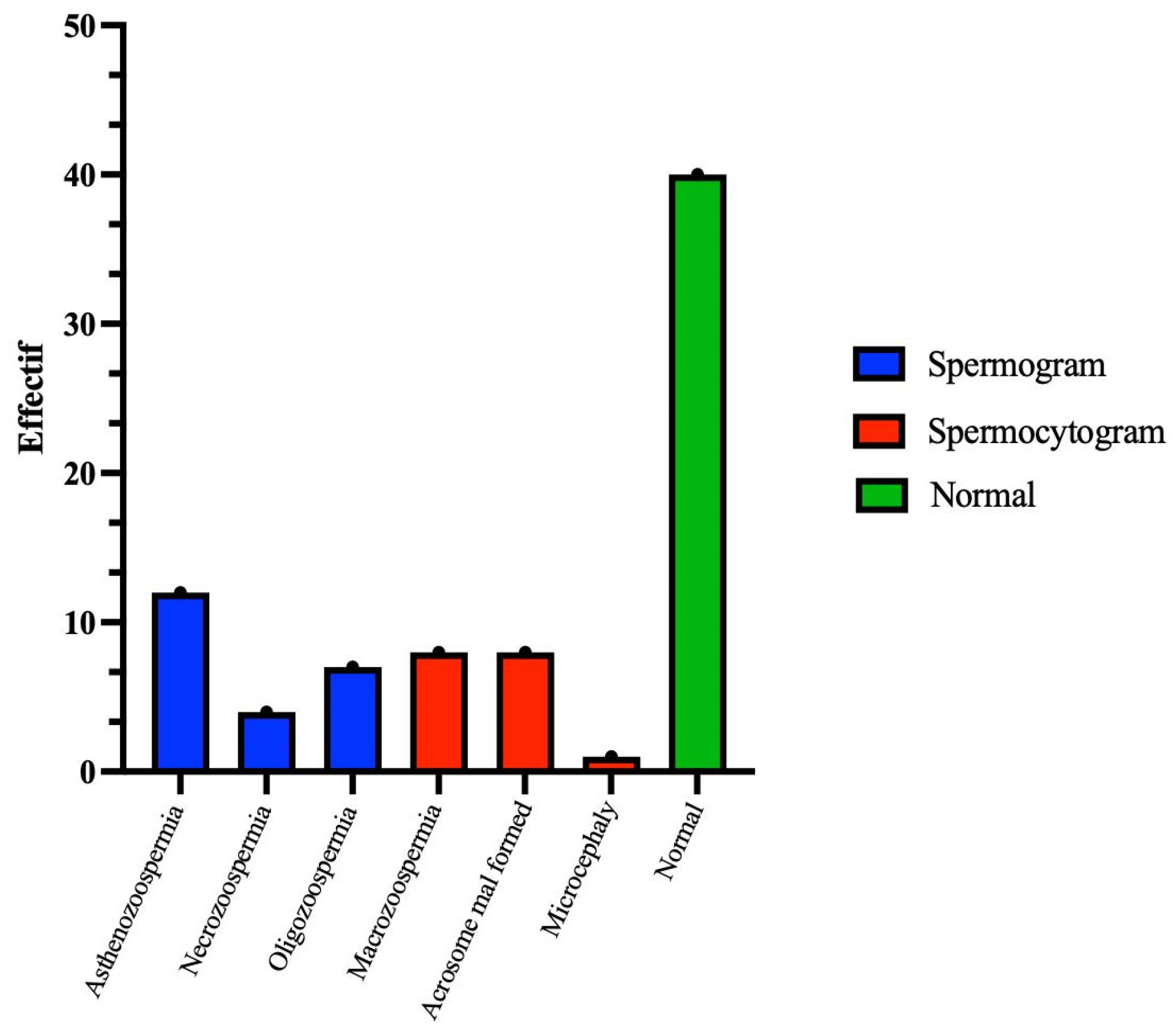

A total of 80 patients of reproductive age were included in this study over a period of two months. Among these patients, forty (50%) were included in the control group. This group had a percentage of typical forms (FTs) greater than 4%. The standard sperm parameters were satisfactory: viability above 50%, a sperm concentration over 15 million/mL, and motility above 40%. Additionally, the genetic material profile was normal, with fewer than 30% abnormalities based on sperm DNA fragmentation and condensation indices (

Figure 1).

The remaining forty (50%) patients were classified as having abnormal sperm. Among them, seventeen (42.5%) presented sperm abnormalities in morphology (monomorphe anomaly), characterized by sperm parameters with TZIs ranging between 1 and 4 and a percentage of typical forms (FTs) less than 4%. Twenty-three (57.5%) exhibited abnormal sperm parameters, with vitality below 50% and/or a sperm count below 15 million/mL and/or sperm motility below 40% (

Figure 2).

3.2. Analysis of the Quality of the Genetic Material in Spermatozoa

3.2.1. Index of SDF by the TUNEL Technique

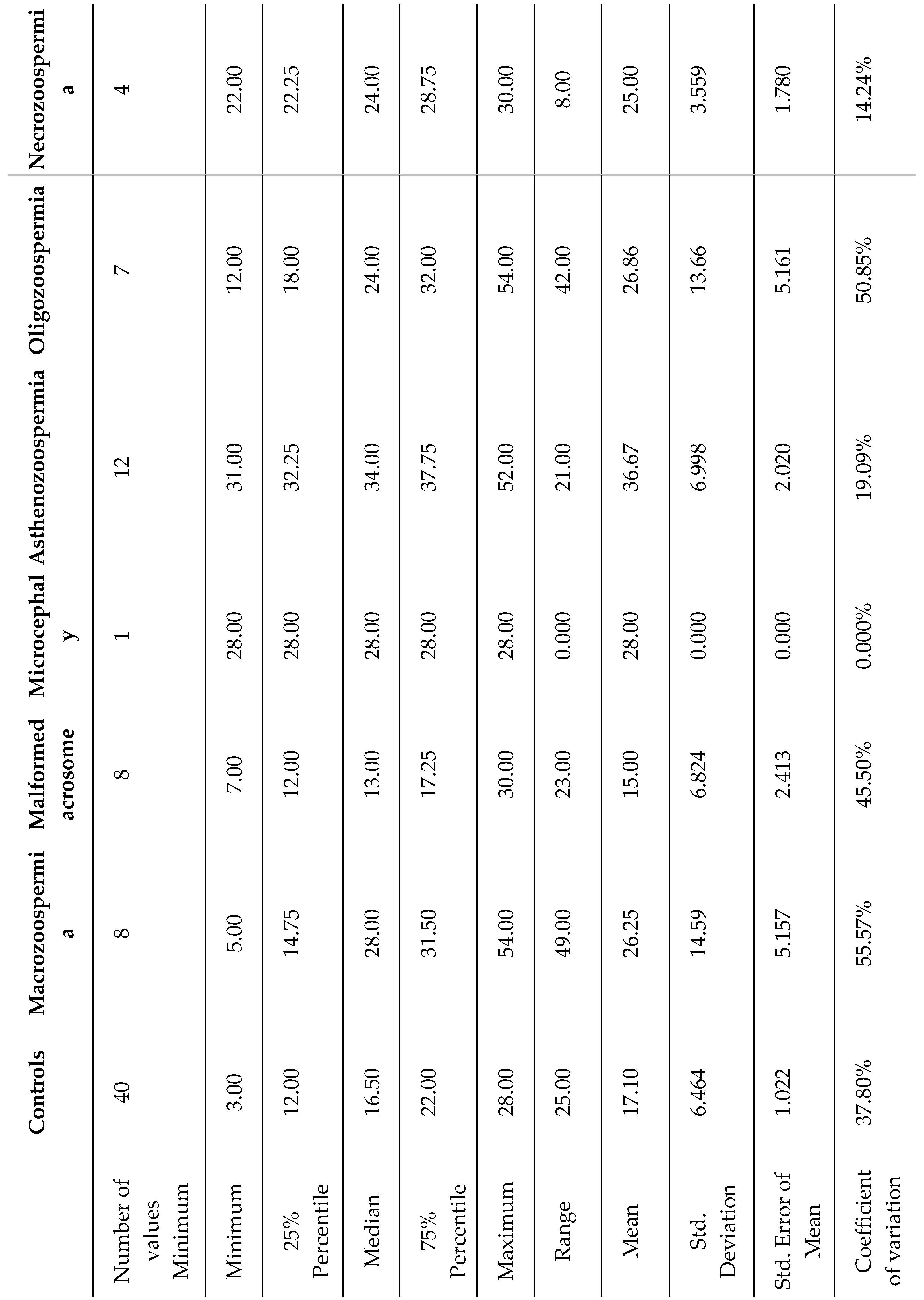

In the group of 40 patients whose sperm abnormalities were detected by spermocytogram and/or spermogram, 25 samples (62.5%) exhibited normal DNA fragmentation (SDF ≤ 30%), whereas the remaining 15 patients (37.5%) presented with elevated DNA fragmentation (SDF > 30%) (

Table 3).

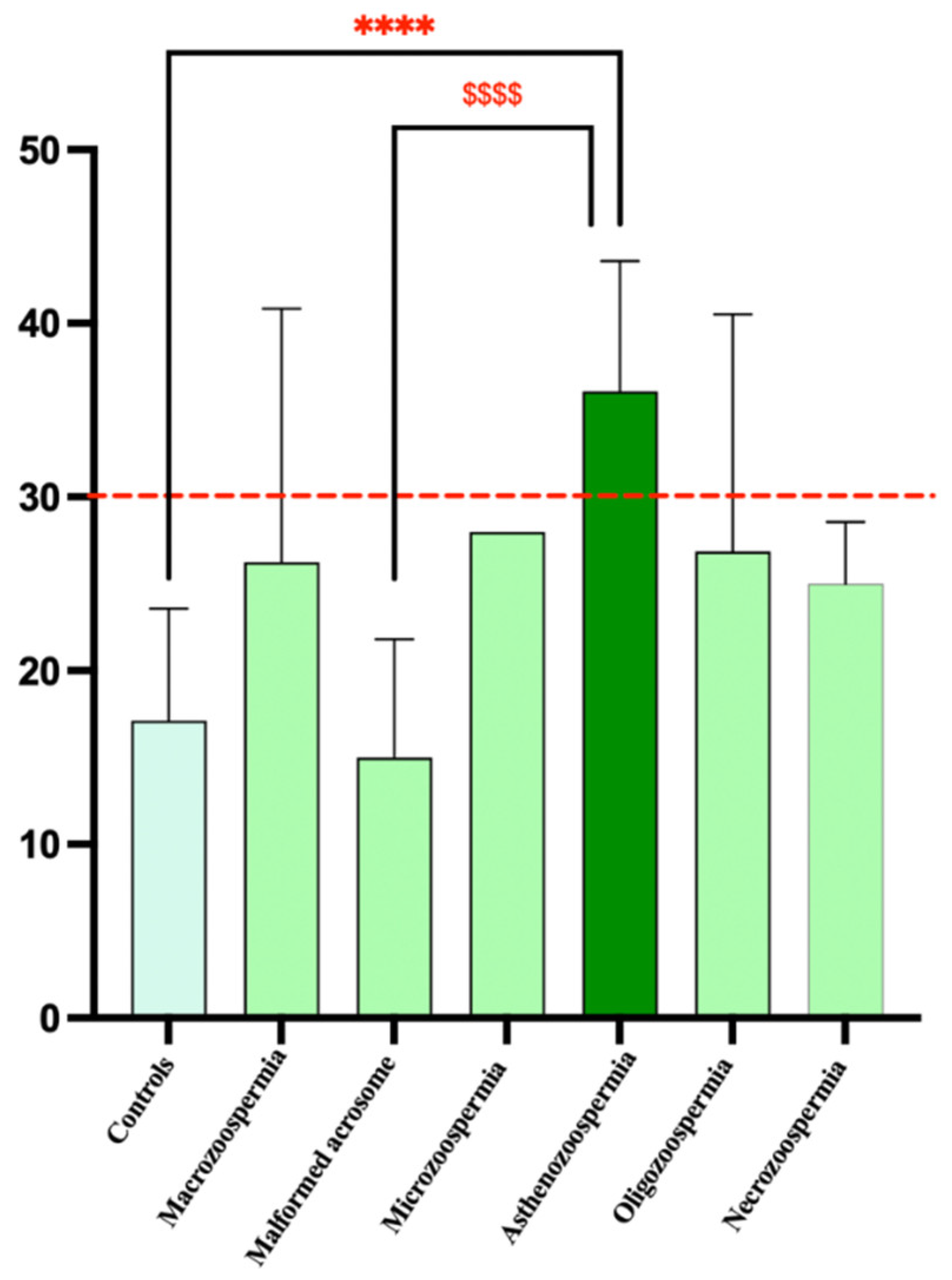

The highest average values of sperm DNA fragmentation were observed in the asthenozoospermia group (36.67) and the necrozoospermia group (28.00). This indicates higher levels of fragmentation in these groups than in the other groups. The standard deviations varied significantly, with the asthenozoospermia group showing high variability (standard deviation of 6.998). In contrast, the microcephaly group showed no variability (standard deviation of 0), likely due to its small sample size (n=1). The coefficient of variation (CV) revealed that the macrozoospermia group presented the highest relative variation (55.57%), followed by the oligozoospermia group (50.85%). This suggests a greater spread of values around the mean in these groups than in the other groups. In contrast, the microcephalic group showed no variation due to its single sample size. The 75th percentile for the asthenozoospermia group was 37.75, which was above the median (34), indicating a positive skew in the distribution of data for this group.

One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of DNA fragmentation on spermatic anomalies (F6, 73 = 9.587, p<0.0001). Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed significant differences between the control and asthenozoospermia groups (p < 0.0001) and between the asthenozoospermia and malformed acrosome groups (p <0.0001). However, there were no significant differences between the other groups (

Figure 3).

3.2.2. Index of SCC by Aniline Blue Staining

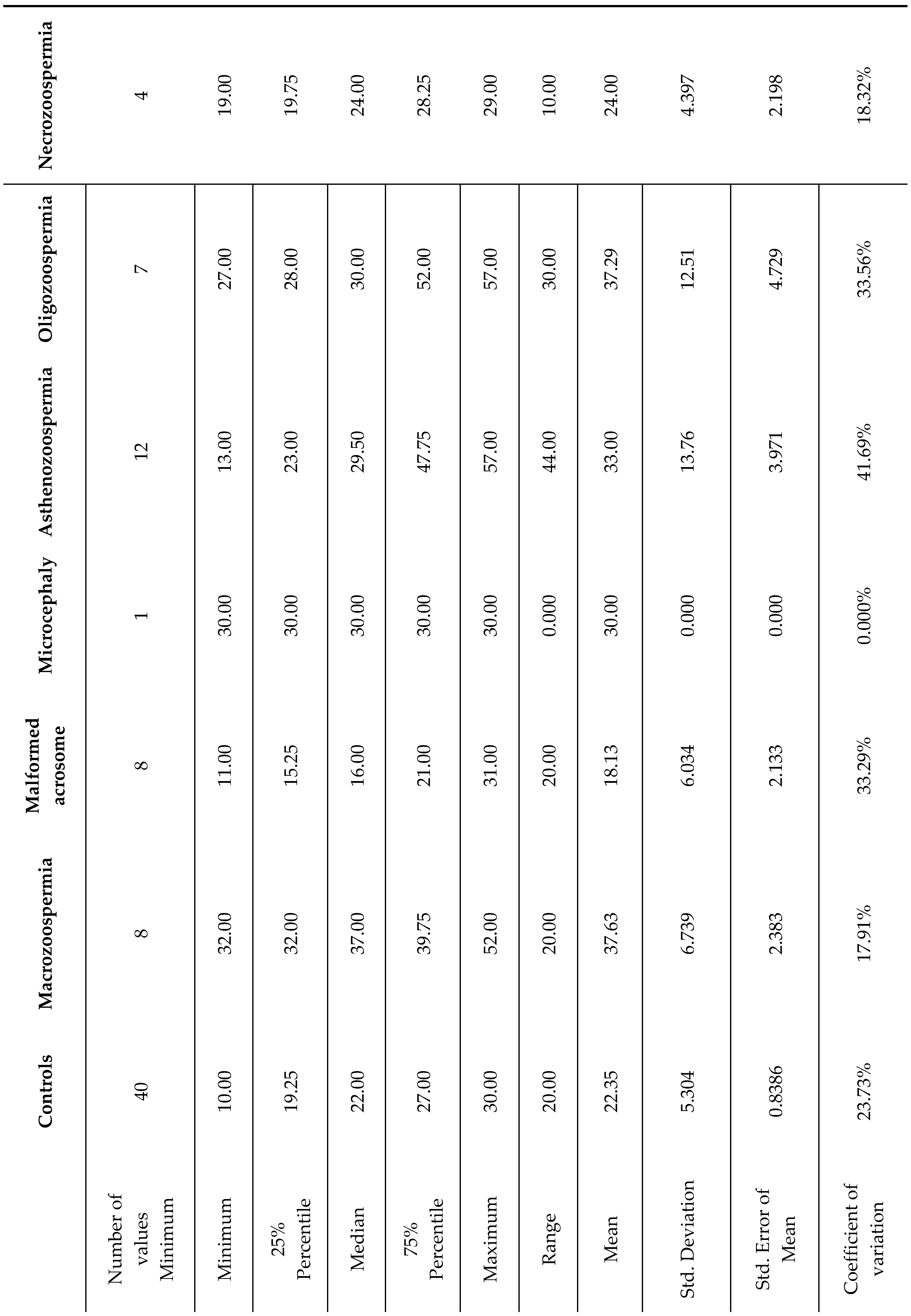

Among the group of 40 patients with sperm abnormalities identified through spermocytogram and/or spermogram analysis, 22 samples (55%) exhibited condensed or normal chromatin (SCC ≤ 30%), whereas the remaining 18 patients (45%) presented decondensed chromatin (SCC > 30%) (

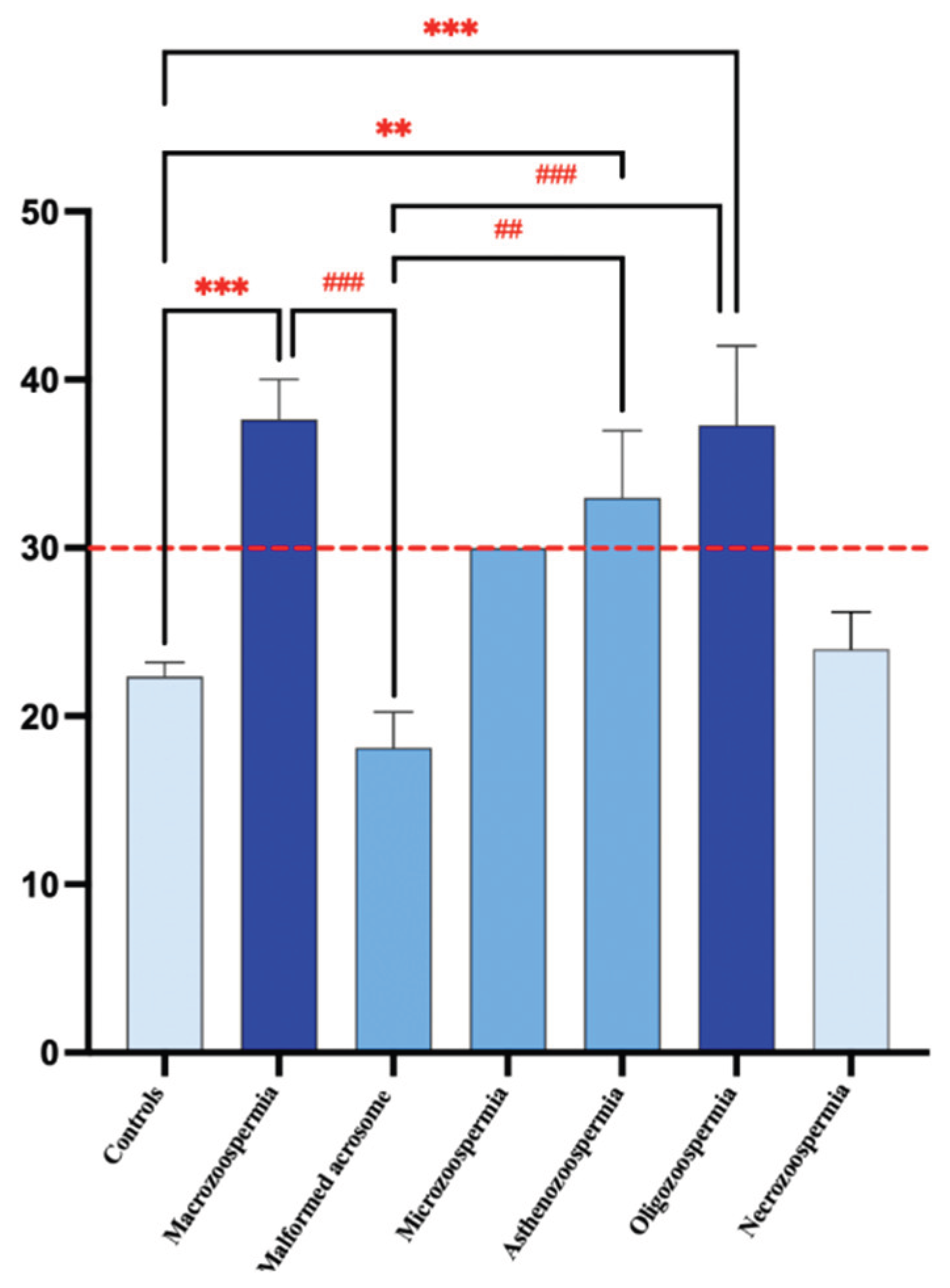

Table 4).

On average, the macrozoospermia and oligozoospermia groups presented the highest values, at 37.63 and 37.29, respectively, indicating elevated levels of sperm chromatin decondensation compared with those of the other groups. The standard deviations differ markedly across groups, with the asthenozoospermia group showing a standard deviation of 13.76, suggesting notable variability within this group. In contrast, the microcephaly group displayed no variation (standard deviation of 0), likely because its sample size was n=1. The coefficient of variation (CV) test revealed that the asthenozoospermia group presented relative variation (41.69%), followed by the oligozoospermia group (33.56%). This suggests a wider spread of values around the mean in these groups than in the other groups. In contrast, the macrozoospermia group showed no variation due to its single sample size. The 75th percentile across all groups is well above the median, indicating a positive skew in the data distribution for these groups.

One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of DNA decondensation on spermatic anomalies (F6, 73= 9.219, p<0.0001). Bonferroni post hoc test revealed significant differences between the macrozoospermia (p =0.0001), asthenozoospermia (p = 0.0030), and oligozoospermia (p = 0.0005) groups and the control group. Additionally, there was a significant difference between the macrozoospermia (p=0.0002), asthenozoospermia (p = 0.0027), and oligozoospermia (p=0.0004) groups and the malformed acrosome group. However, no significant differences were found between the other groups (p > 0.99) (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate the interplay between sperm DNA fragmentation, sperm chromatin condensation, and conventional sperm parameters assessed through standard semen analysis. A total of 80 male patients undergoing infertility assessment were enrolled, aiming to explore the correlation between sperm nuclear quality and sperm parameters. SDF was measured using the TUNEL assay, while SCC was assessed using aniline blue staining.

Our results revealed statistically significant differences across several sperm parameters, underscoring the importance of integrating nuclear quality tests (SDF and SCC) into routine male fertility evaluations. Traditional semen analyses (spermogram, spermocytogram), although informative, do not reflect the full extent of sperm nuclear integrity, which plays a critical role in fertilization and embryonic development.

Interestingly, while some abnormalities identified via basic tests such as asthenozoospermia and teratozoospermia showed strong associations with either fragmentation or decondensation indices. These associations appeared to be indirect and multifactorial, as supported in the literature [

10]. In some patients, anomalies were reflected at both nuclear indices (SDF > 30% and SCC > 30%), suggesting a cumulative effect of multiple pathological processes on sperm quality.

The control group exhibited relatively low levels of DNA fragmentation (17.1 ± 6.46) and chromatin decondensation (22.35 ± 5.30) compared to groups with abnormal semen parameters. This sharp contrast emphasizes the relation between sperm abnormalities and nuclear quality and supports previous findings highlighting the impact of oxidative stress and abnormal spermatogenesis on DNA integrity [

11] [

12].

Sperm DNA Fragmentation

Sperm DNA is the carrier of paternal genetic information, and its structural integrity is essential for fertilization and embryo viability. DNA damage can be induced by intrinsic factors such as defective chromatin packaging and extrinsic factors; oxidative stress, environmental toxins. Under oxidative conditions, reactive oxygen species (ROS) can induce single- and double-strand breaks in DNA, thereby compromising sperm function [

13].

In our study, a significant increase in SDF was found in patients with asthenozoospermia compared to the control group. The 12 patients with asthenozoospermia (30% of the cohort) with sperm exhibiting FT values > 4% and motility < 32%. this alteration in DNA can be explained by the environment of the spermatozoa, which is rich in free radicals, inducing oxidative stress that directly degrades the DNA [

14] the decrease in motility can also be explained by the fact that a motile spermatozoon is characterized by an intact structure, while oxidative stress degrades not only the DNA but also the phospholipid structure of the sperm [

12], directly affecting their motility. Furthermore, the presence of elevated SDF in sperm with asthenozoospermia suggests a double impairment: impaired mitochondrial activity required for motility and increased oxidative damage affecting both membrane and nuclear DNA. This is consistent with studies showing that mitochondrial ROS production is a key driver of both motility loss and fragmentation [

15].

Sperm Chromatin Condensation

The structural and functional organization of human spermatozoa is extremely complex and relies on a unique compaction system. The condensation of human sperm DNA is regulated by specific proteins that ensure the precise control of condensation and decondensation over time [

16]. At certain stages of embryonic development, DNA must be decondensed to allow protein synthesis, while at other times, it must be condensed to protect it from degradation and damage. Any disruption in this process can lead to decondensed chromatin, making DNA more vulnerable to damage. This delicate balance is maintained by the structural organization of DNA [

17].

In this study, we observed a significant increase in chromatin decondensation in patients with macrozoospermia compared to controls (p < 0.00001). This subgroup (20% of altered patients) showed a high percentage of monomorphic anomalies with FT < 4%. Macrozoospermia has been associated with chromosomal segregation defects and protamine deficiency, and recent studies have suggested the involvement of mutations in the AURKC gene (aurora kinase C), which disrupts chromatin remodeling during spermatogenesis [

18]. In addition to genetic factors, oxidative stress has been shown to disrupt the chromatin condensation process by interfering with protamine cross-linking and inducing premature chromatin unpacking [

6]. This dual contribution of genetic and environmental stressors could explain the elevated SCC values observed in our macrozoospermia group [

19,

20].

Interplay Between SDF and SCC

Interestingly, while SDF and SCC represent distinct processes (strand breakage vs. compaction failure), they are often interrelated. Incomplete chromatin condensation has been proposed as a precursor to DNA fragmentation, as loosely packed DNA is more susceptible to ROS and endonuclease attack [

15,

21]. In our study, patients with elevated SCC often exhibited high SDF, suggesting that impaired chromatin packaging may predispose spermatozoa to fragmentation, a hypothesis supported by recent findings [

21,

22]. This suggests that assessing both parameters provides a more comprehensive picture of nuclear sperm quality than either marker alone. Clinically, this has implications for ART, particularly intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), where selecting sperm with intact DNA and proper chromatin compaction may improve fertilization and pregnancy outcomes [

23].

5. Conclusions

In the future, further investigations would be beneficial to better understand the underlying mechanisms of sperm DNA decondensation and fragmentation. Specifically, exploring genetic pathways and environmental factors could provide valuable insights for developing new therapeutic strategies.

Additionally, the integration of advanced DNA sequencing and proteomics techniques could help identify specific biomarkers associated with male infertility. These biomarkers could serve as targets for personalized therapeutic interventions, thereby improving the success rates of assisted reproductive technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O. Adli., N. Louanjli. and R. Aboutaeib; methodology, O. Adli; validation, O. Adli, R. Aboutaeib; investigation, O. Adli; resources, N. Louanjli; writing—original draft preparation, O. Adli; writing—review and editing, O. Adli, R. Aboutaeib; supervision, R. Aboutaeib; funding acquisition, O. Adli, N. Louanjli and R. Aboutaeib. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Center “20 Aout” (protocol code: N° 9bis/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was also obtained from the patients for the use of their information and results as part of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Moroccan National Center for Scientific and Technical Research (CNRST) for the financial support provided through the PASS doctoral scholarship (2024–2027). This work was presented at the 40th edition of the Société d’Andrologie de Langue Française (SALF) in Marseille, France, as well as at the 50th edition of the American Society of Andrology (ASA) and the 13th edition of the International Congress of Andrology (ICA) in Washington, D.C, United States, and at the International Congress of the Moroccan Association of Research and Ethics in Morocco (MARE). We also thank the organizers of these conferences for the opportunity to share our findings and engage with the international scientific community.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ART |

Assisted Reproductive Technology |

| AURKC |

Aurora Kinase C |

| CASA |

computer-assisted sperm analysis system |

| FTs |

typical forms |

| ICSI |

intracytoplasmic sperm injection |

| IUI |

intrauterine insemination |

| IVF |

vitro fertilization |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| SCC |

Sperm Chromatin Condensation |

| SDF |

Sperm DNA Fragmentation |

| TZI |

teratozoospermia index |

Table A1.

Sperm motility parameters.

Table A1.

Sperm motility parameters.

| Type (a) |

Rapid progressive |

| Type (b) |

Nonprogressive |

| Type (c) |

Immotile |

Table A2.

Standards for sperm.

Table A2.

Standards for sperm.

| Sperm parameter |

Threshold values |

| Ejaculated volume |

> 1.4 mL |

| Sperm concentration (million/mL) |

> 16 million |

| Total sperm number (million/ejaculate) |

> 39 million |

| Total motility (progressive + nonprogressive) |

> 42% |

| Vitality |

>58% |

References

- Ghallam, A.; Bouasria, L.; Zirari, H. Medically assisted procreation: A new legal framework to overcome infertility in Morocco in the context of energy optimization. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences, 2023; Volume 412, p. 01057. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, I.K.; Easley, C.A. Recent developments in in vitro spermatogenesis and future directions. Reproductive Medicine 2023, 4, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniek, J.M.; Lapin, C.D.; Jarvi, K.A. Genetics of CFTR and male infertility. Translational andrology and urology 2021, 10, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, D.V.; Shah, R.; Gajbhiye, R.K. Genetics of male infertility–present and future: a narrative review. Journal of human reproductive sciences 2021, 14, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Parekh, N.; Selvam, M.K.P.; Henkel, R.; Shah, R.; Homa, S.T.; Harlev, A. Male oxidative stress infertility (MOSI): proposed terminology and clinical practice guidelines for management of idiopathic male infertility. The world journal of men’s health 2019, 37, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, E.; Muratori, M.; Marchiani, S.; Tamburrino, L.; Fallet, C. Fragmentation et/ou décondensation de l’ADN spermatique: quelles conséquences? Journal de gynécologie obstétrique et biologie de la reproduction 2010, 39, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. In Who laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, J.; Eustache, F.; David, G. Standardization of the morphological assessment of human spermatozoa according to modified David’s classification. Andrologie 2000, 10, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, T.F.; Acosta, A.A.; Simmons, K.F.; Swanson, R.J.; Matta, J.F.; Oehninger, S. Predictive value of abnormal sperm morphology in in vitro fertilization. Fertility and sterility 1988, 49, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candela, L.; Boeri, L.; Capogrosso, P.; Cazzaniga, W.; Pozzi, E.; Belladelli, F.; Salonia, A. Correlation among isolated teratozoospermia, sperm DNA fragmentation and markers of systemic inflammation in primary infertile men. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0251608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küçük, N. Sperm DNA and detection of DNA fragmentations in sperm. Turkish journal of urology 2018, 44, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQueen, D.B.; Zhang, J.; Robins, J.C. Sperm DNA fragmentation and recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertility and sterility 2019, 112, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, R.J.; Koppers, A.J. Apoptosis and DNA damage in human spermatozoa. Asian journal of andrology 2010, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawe, V.Y.; Alvarez, C.R.; Uriondo, H.W.; Alvarez, G.; Lipowicz, R.; Chemes, H. Relationship between chromatin ultrastructure and DNA fragmentation in human spermatozoa. Fertility and Sterility 2009, 92, S142–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ferreyra, J. Sperm DNA fragmentation and its relation with fertility. In New discoveries in embryology; IntechOpen, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, W.S. Function of sperm chromatin structural elements in fertilization and development. MHR: Basic science of reproductive medicine 2009, 16, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Agarwal, A. The role of sperm chromatin integrity and DNA damage on male infertility. Open Reprod Sci J 2011, 3, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Khelifa, M.; Zouari, R.; Harbuz, R.; Halouani, L.; Arnoult, C.; Lunardi, J.; Ray, P.F. A new AURKC mutation causing macrozoospermia: implications for human spermatogenesis and clinical diagnosis. Molecular human reproduction 2011, 17, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torregrosa, N.; Domínguez-Fandos, D.; Camejo, M.I.; Shirley, C.R.; Meistrich, M.L.; Ballescà, J.L.; Oliva, R. Protamine 2 precursors, protamine 1/protamine 2 ratio, DNA integrity and other sperm parameters in infertile patients. Human Reproduction 2006, 21, 2084–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadoune, J.P.; Mayaux, M.J.; Guihard-Moscato, M.L. Correlation between defects in chromatin condensation of human spermatozoa stained by aniline blue and semen characteristics: Beziehungen zwischen Defekten der chromatinkondensation menschlicher spermatozoen, die mittels anilinblau gefärbt wurden und spermacharakteristika. Andrologia 1988, 20, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Larson-Cook, K.L.; Brannian, J.D.; Hansen, K.A.; Kasperson, K.M.; Aamold, E.T.; Evenson, D.P. Relationship between the outcomes of assisted reproductive techniques and sperm DNA fragmentation as measured by the sperm chromatin structure assay. Fertility and sterility 2003, 80, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, L.; Zini, A.; Dyachenko, A.; Ciampi, A.; Carrell, D.T. A systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effect of sperm DNA damage on in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome. Asian journal of andrology 2017, 19, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Evenson, D.P. Sperm Chromatin Structure Assay (SCSA®): 30 years of experience with the SCSA®. Sperm chromatin: Biological and clinical applications in male infertility and assisted reproduction 2011, 125–149. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).