Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

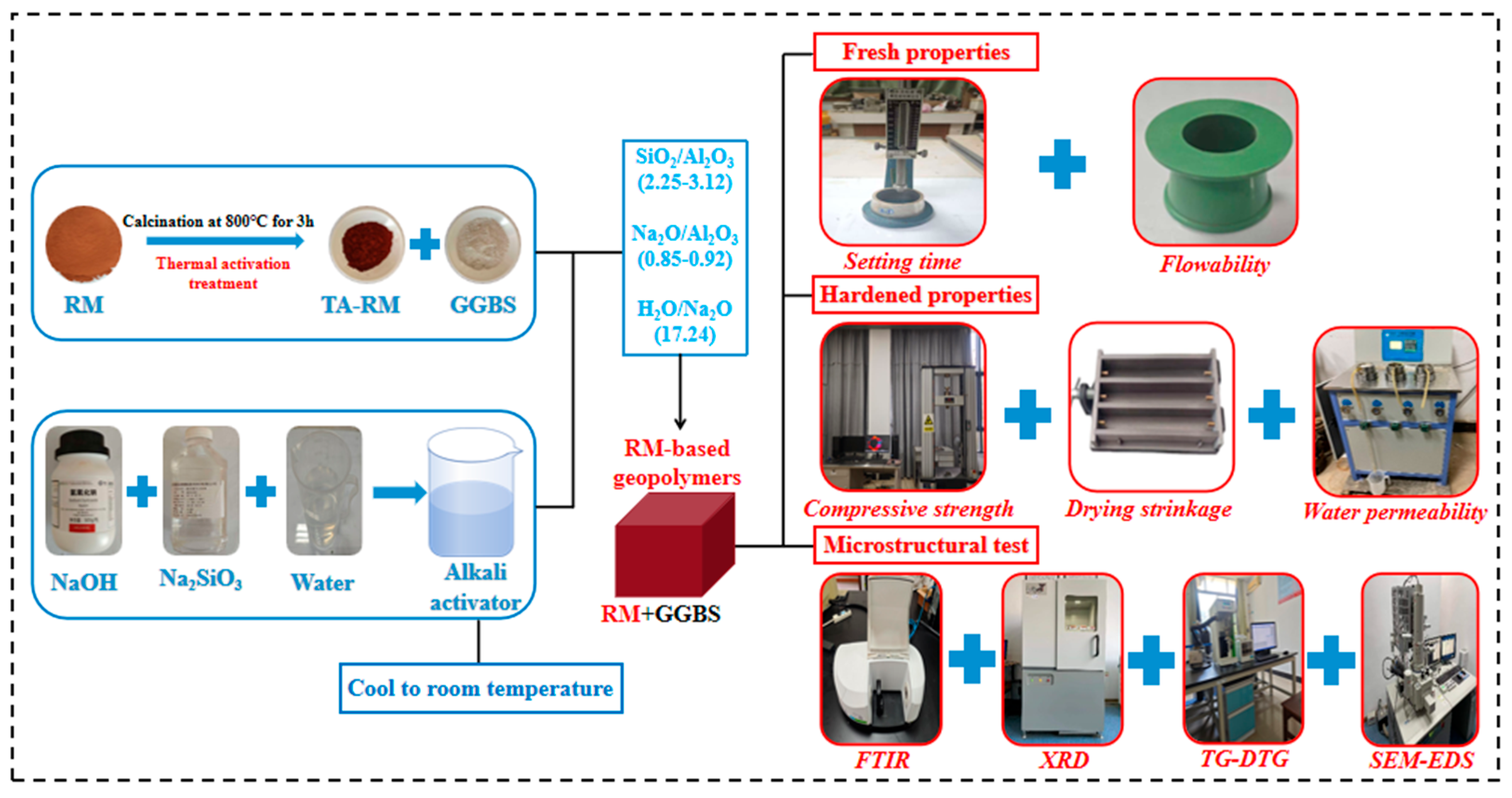

2. Experimental Program

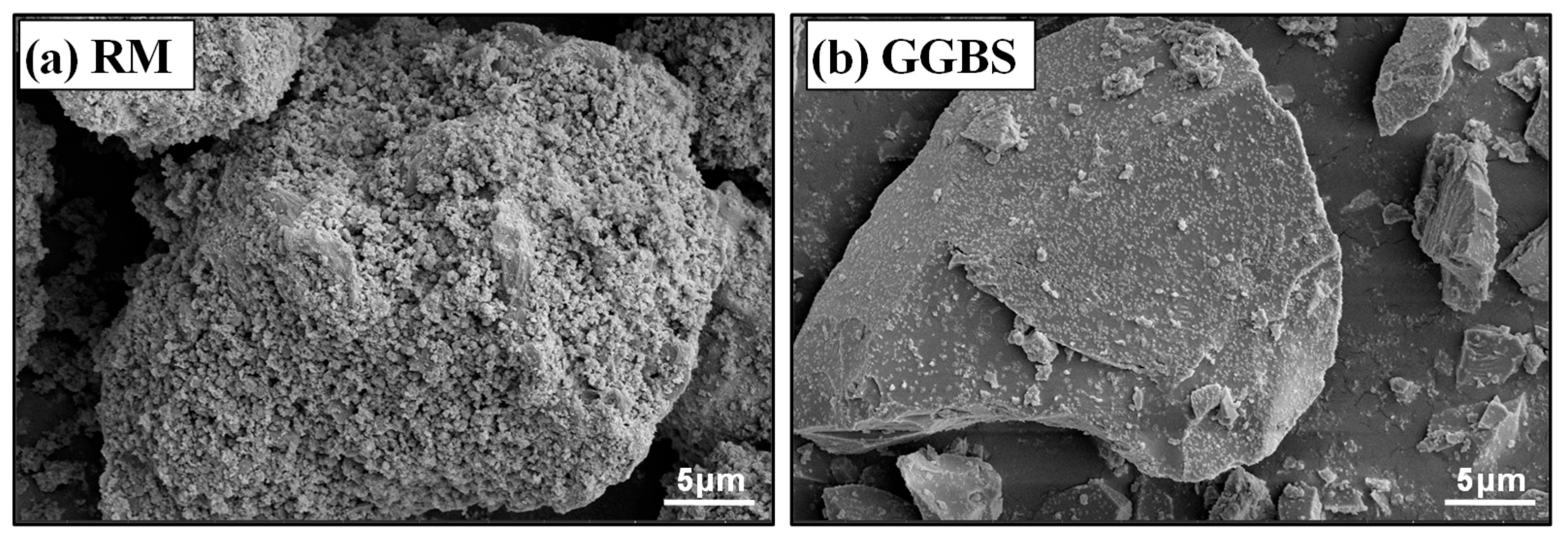

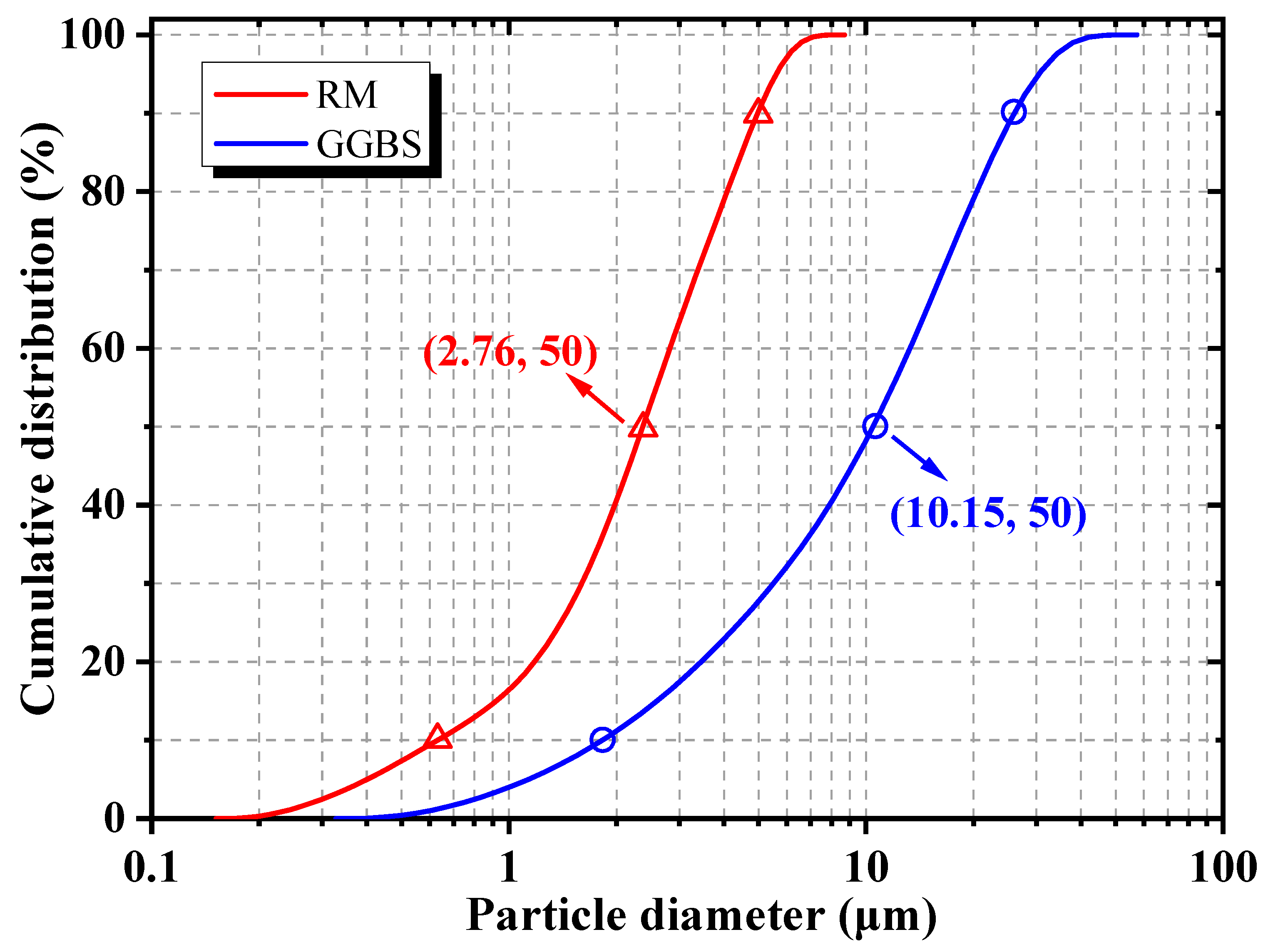

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Material Design and Preparation

2.3. Testing Methods

2.3.1. Flowability

2.3.2. Setting Time

2.3.3. Compressive Strength

2.3.4. Drying Shrinkage

2.3.5. Water Permeability

2.3.6. SEM-EDS Analysis

2.3.7. FTIR Analysis

2.3.8. XRD Analysis

2.3.9. TG-DTG Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fresh Properties and Hardened Properties

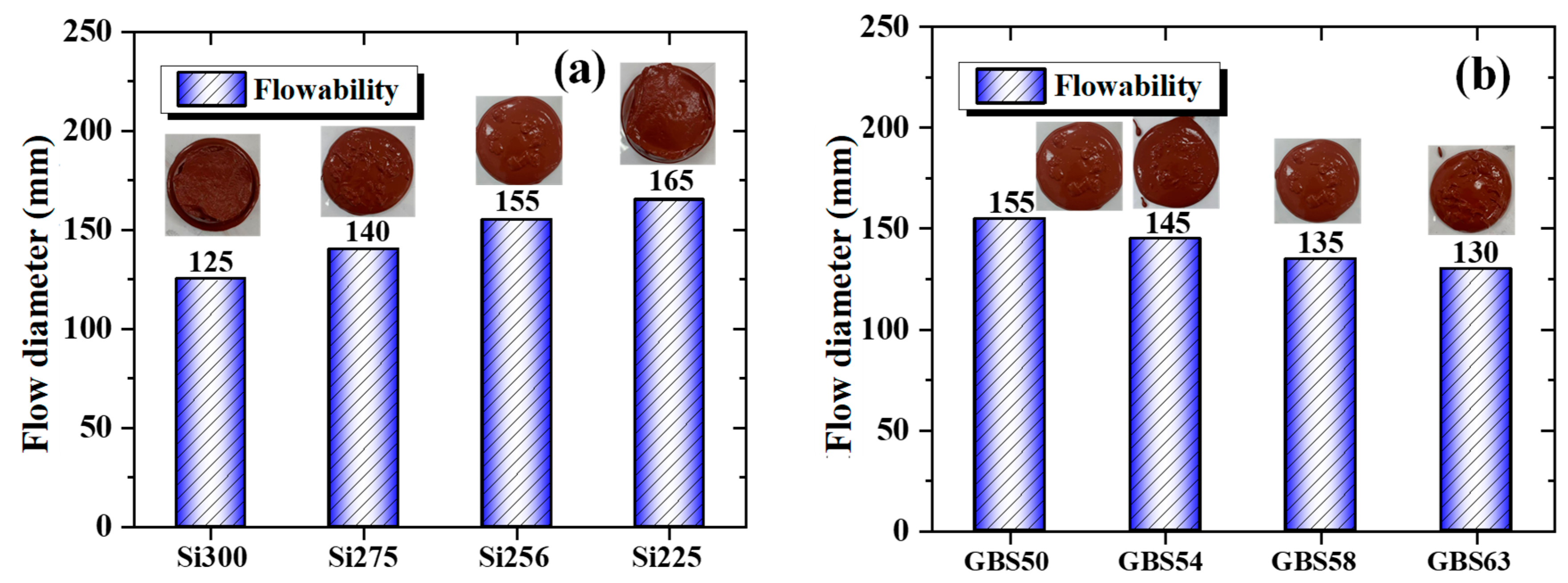

3.1.1. Flowability

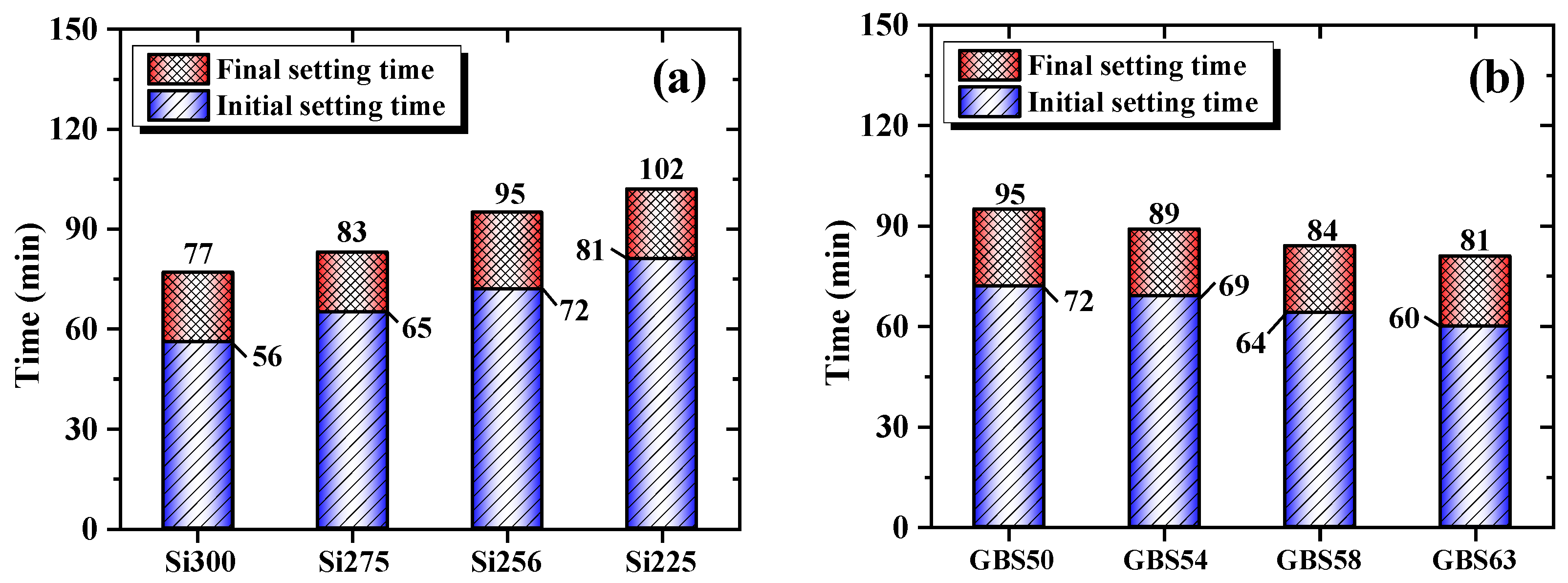

3.1.2. Setting Time

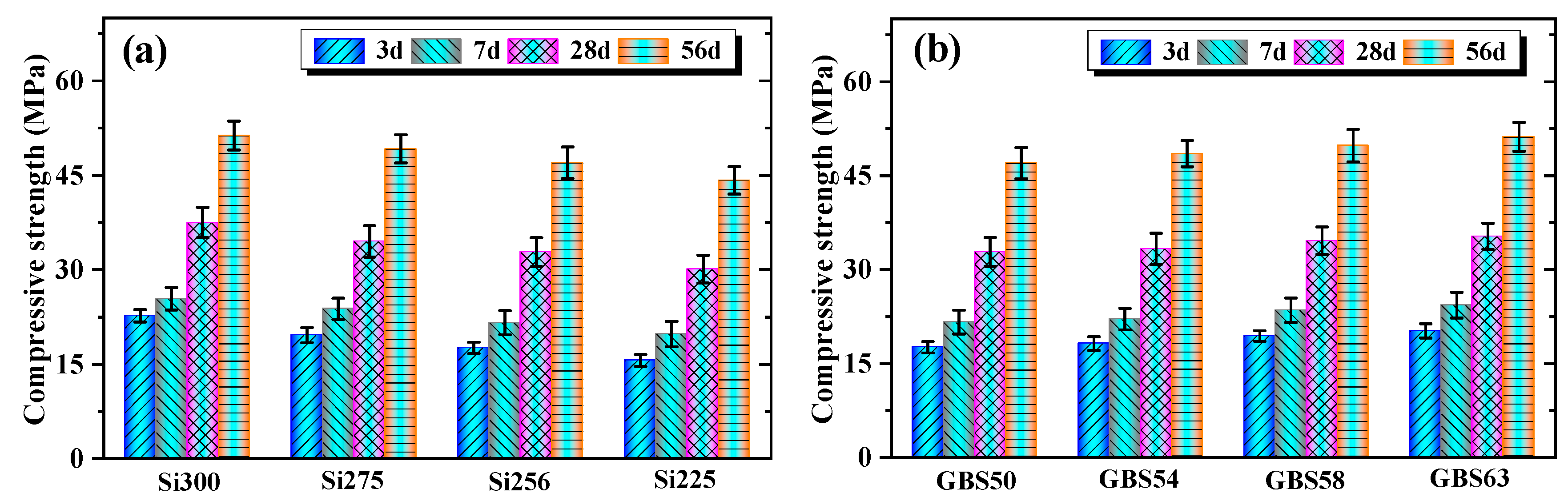

3.1.3. Compressive Strength

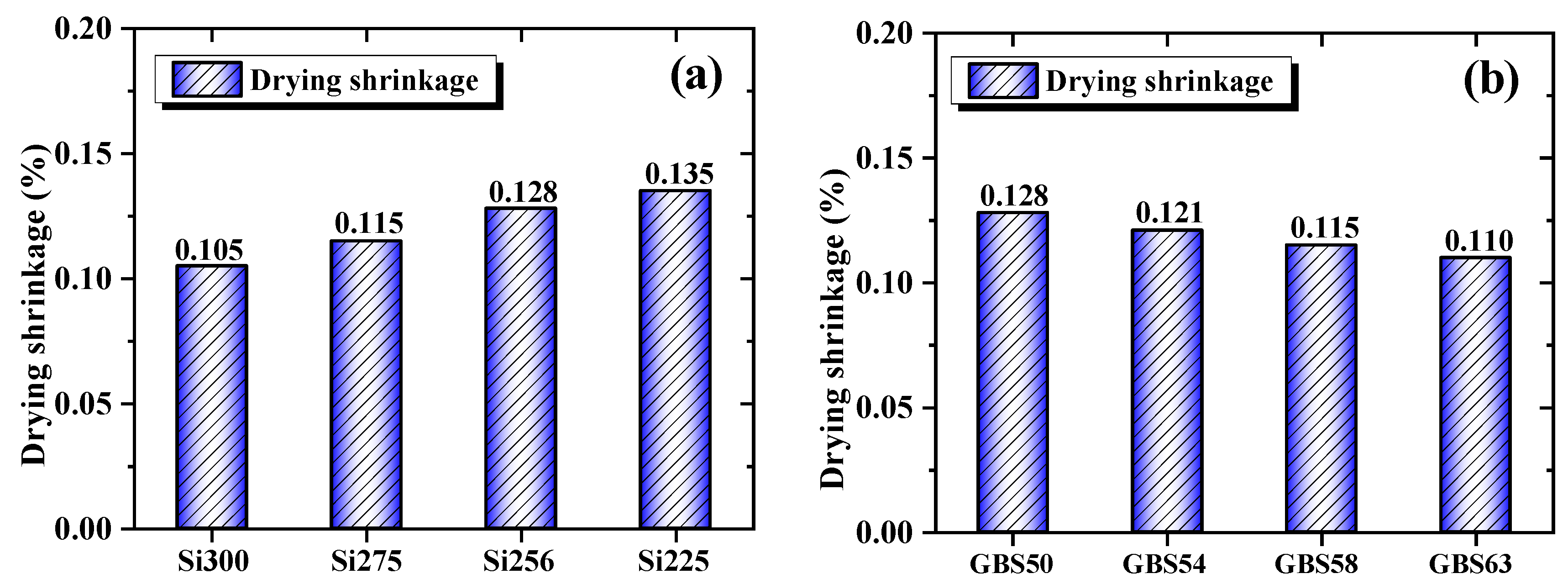

3.1.4. Drying Shrinkage

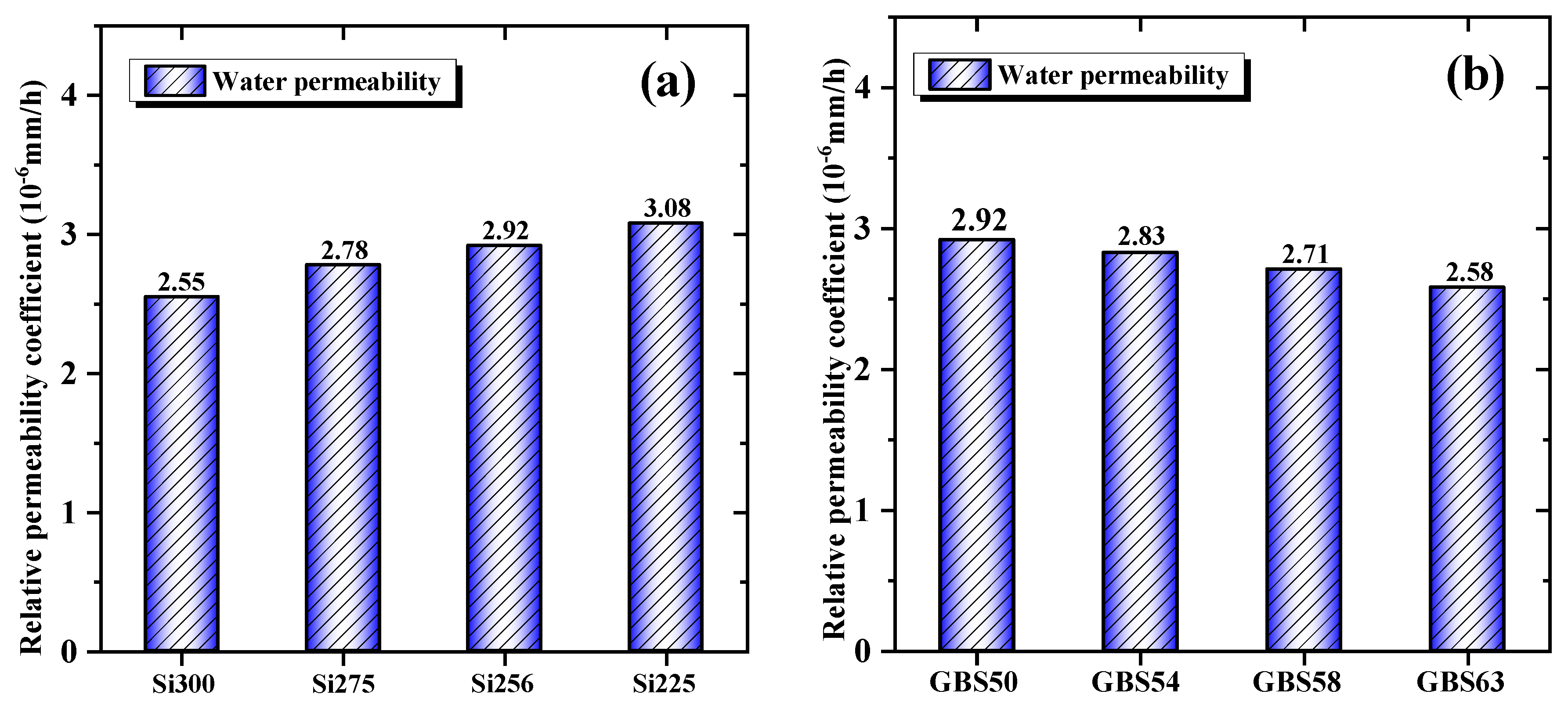

3.1.5. Water Permeability

3.2. Microstructure

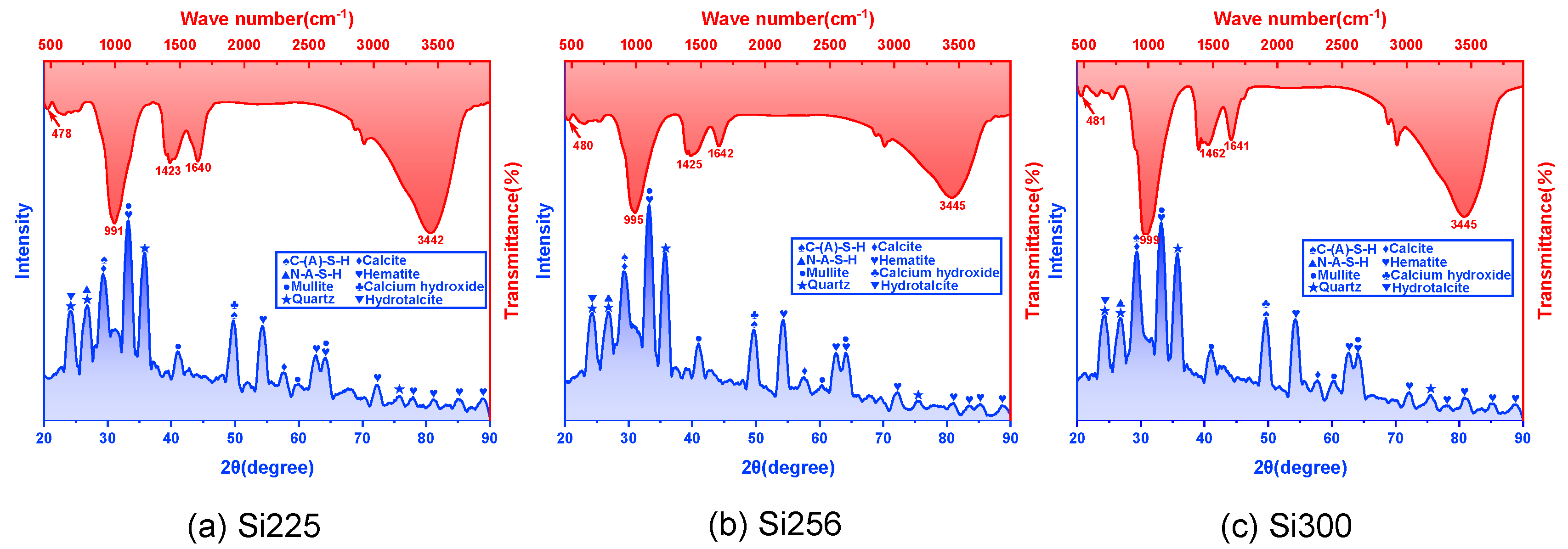

3.2.1. FTIR and XRD Analyses

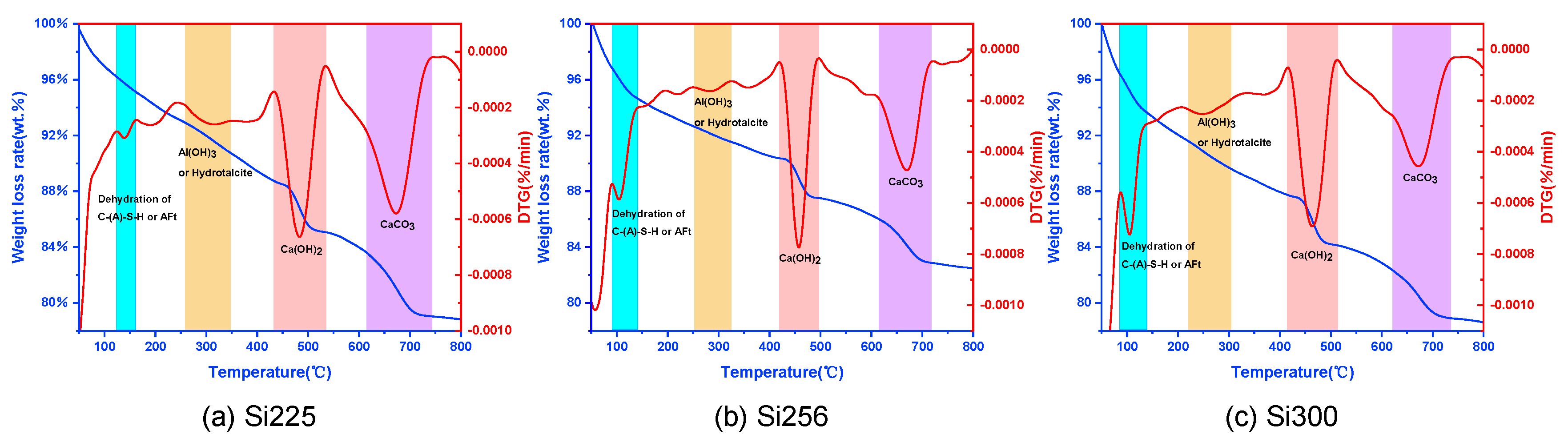

3.2.2. TG-DTG Analysis

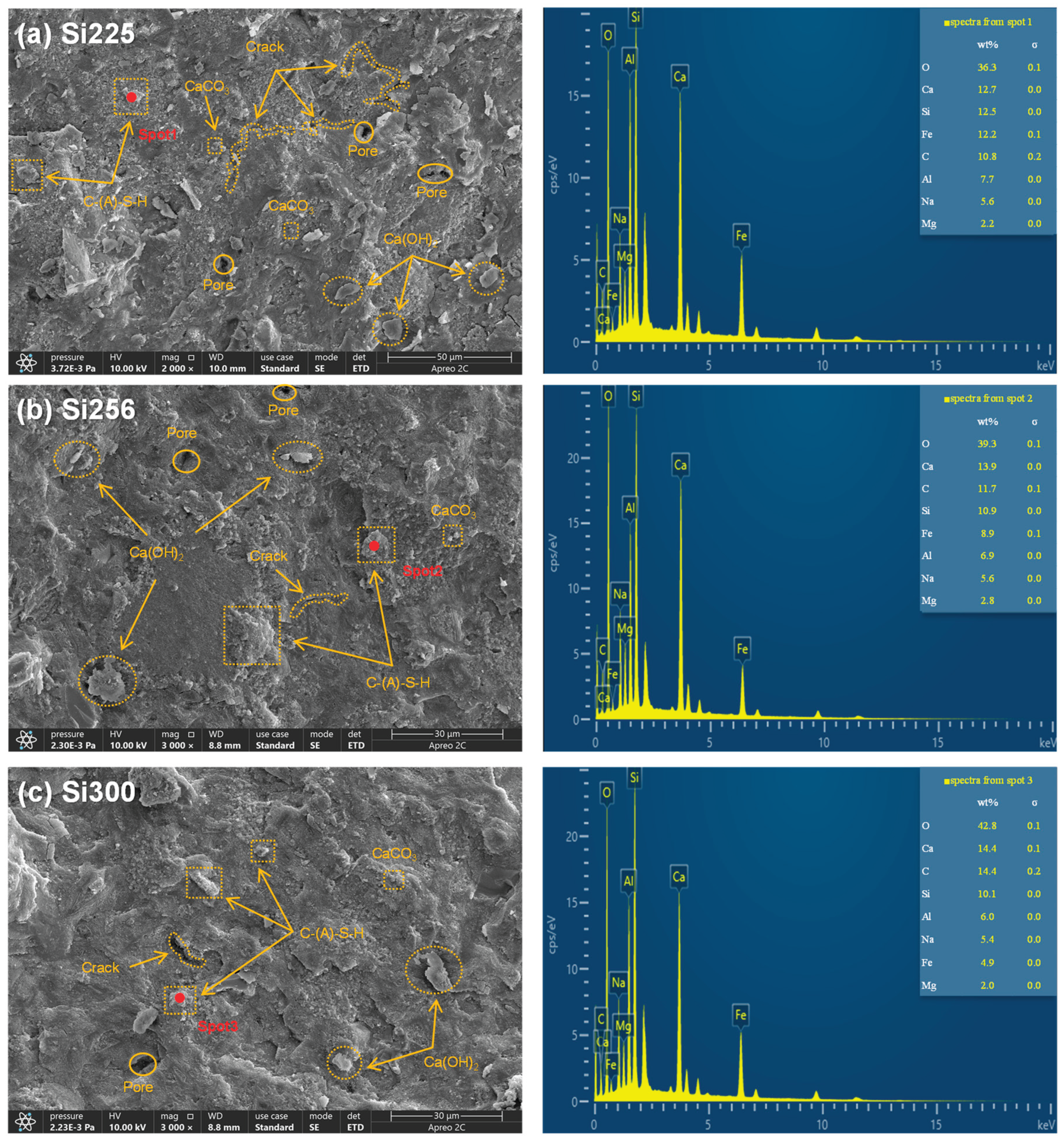

3.2.3. SEM-EDS Analysis

3.3. Sustainability Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The high SiO2/Al2O3 ratio and increased GGBS addition raised the concentrations of SiO2 and Ca²⁺ in the system, respectively. This accelerated the formation of a three-dimensional gel network, resulting in reduced setting time and flowability of RM-based geopolymers.

- (2)

- Increasing the SiO₂/Al₂O₃ ratio and GGBS addition enhanced the 56-day compressive strength by 6.3–16.1% and 3.2–8.9%, respectively. The higher SiO₂/Al₂O₃ ratio increased the concentration of [SiO₄]⁴⁻ units and facilitated the dissolution of Si and Al. GGBS promoted the release of Ca²⁺ and exothermic reactions, thereby improving the strength of RM-based geopolymers.

- (3)

- When the SiO₂/Al₂O₃ ratio increased, drying shrinkage was reduced by 22.2% due to the enhanced formation of C-(A)-S-H/N-A-S-H gels and a decrease in mesopore content. High GGBS addition reduced the shrinkage by 14.1%, primarily promoting C-(A)-S-H gels formation, facilitating CaCO₃ crystallization and reducing the evaporation of free water. Both approaches reduced water permeability by optimizing the pore structure and enhancing the densification of the gel network.

- (4)

- The primary hydration products of RM-based geopolymers included C-(A)-S-H, N-A-S-H, calcite, hydrotalcite and calcium hydroxide. These products effectively filled the pores, leading to a more compact microstructure. SEM-EDS analysis further showed that raising the SiO₂/Al₂O₃ ratio reduced crack length and pore quantity. CaCO₃, Ca(OH)₂ and C-(A)-S-H formed an interpenetrating gel-crystal network structure. The Ca/Si ratio in the C-(A)-S-H gel increased from 1.02 to 1.43, and the Si/Al ratio rose from 1.62 to 1.68.

- (5)

- In comparison to the referenced RM-based geopolymers, the CO₂ emission and costs in this study were reduced by 13.13%–44.33% and 3.64%–39.68%, respectively. The CO₂ emissions of RM-based geopolymers were closely influenced by the SiO₂/Al₂O₃ ratio. Adjusting the SiO₂/Al₂O₃ ratio effectively reduced CO₂ emissions, thereby promoting sustainability.

Acknowledgements

References

- Y. Zhao, Y. Zheng, J. He, K. Cui, P. Shen, G. Peng, R. Guo, D. Xia, C.S. Poon, Production of carbonates calcined clay cement composites via CO2-assisted vigorous stirring, Cement and Concrete Composites. 2025, 163, 106181. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, H.F. Dong, X.S. Zhao, K. Wang, X.J. Gao, Utilization of bayer red mud for high-performance geopolymers: competitive roles of different activators, Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Ghafoor, N. Rakhimova, C. Shi, One part geopolymers: A comprehensive review of advances and key challenges, J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113112. [CrossRef]

- A. Hassan, C. Zhang, Dynamic and static behaviour of geopolymer concrete for sustainable infrastructure development: Prospects, challenges, and performance review, Compos. Struct. 2025, 359, 118984. [CrossRef]

- K. Guo, H. Dong, J. Zhang, L. Zhang, Z. Li, Experimental study of Alkali-Activated cementitious materials using thermally activated red mud: Effect of the Si/Al ratio on fresh and mechanical properties, Buildings, 2025, 15(4), 565. [CrossRef]

- X. Jiang, R. Xiao, M.M. Zhang, W. Hu, Y. Bai, B.S. Huang, A laboratory investigation of steel to fly ash-based geopolymer paste bonding behavior after exposure to elevated temperatures. Construction and Building Materials. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Karthik, K. Saravana Raja Mohan, G. Murali, S.R. Abid, S. Dixit, Impact of various fibers on mode I, III and I/III fracture toughness in slag, fly Ash, and silica fume-based geopolymer concrete using edge-notched disc bend specimen, Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 134, 104751. [CrossRef]

- H. Bilal, T.F. Chen, M. Ren, X.J. Gao, A.S. Su: Influence of silica fume, metakaolin & sbr latex on strength and durability performance of pervious concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 275. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E.A. Abdelrahman, Y.G. Abou El-Reash, H.M. Youssef, Y.H. Kotp, R.M. Hegazey, Utilization of rice husk and waste aluminum cans for the synthesis of some nanosized zeolite, zeolite/zeolite, and geopolymer/zeolite products for the efficient removal of Co(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II) ions from aqueous media, J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123813. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, A. Wang, Y. Zhu, J. Dai, Q. Xu, K. Liu, F. Hao, D. Sun, Manufacturing ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete (UHPGC) with activated coal gangue for both binder and aggregate, Composites Part B: Engineering. 2024, 284, 111723. [CrossRef]

- Y.S. Wudil, A. Al-Fakih, M.A. Al-Osta, M.A. Gondal, Intelligent optimization for modeling carbon dioxide footprint in fly ash geopolymer concrete: A novel approach for minimizing CO2 emissions, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12(1), 111835. [CrossRef]

- L. Qin, X.J. Gao, Properties of coal gangue-portland cement mixture with carbonation. Fuel. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, Y. Han, F. He, P. Gao, S. Yuan, Characteristic, hazard and iron recovery technology of red mud - a critical review, J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126542. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, X. Min, Y. Ke, D. Liu, C. Tang, Preparation of red mud-based geopolymer materials from MSWI fly ash and red mud by mechanical activation, Waste Manage. 2019, 83, 202–208. [CrossRef]

- U. Zakira, K. Zheng, N. Xie, B. Birgisson, Development of high-strength geopolymers from red mud and blast furnace slag, J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135439. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, Y. Zhuge, X. Chen, W. Duan, R. Fan, L. Outhred, L. Wang, Micro-chemomechanical properties of red mud binder and its effect on concrete, Composites Part B: Engineering. 2023, 258, 110688. [CrossRef]

- T. Qin, H. Luo, R. Han, Y. Zhao, L. Chen, M. Liu, Z. Gui, J. Xing, D. Chen, B. He, Red mud in combination with construction waste red bricks for the preparation of Low-Carbon binder materials: Design and material characterization, Buildings, 2024, 14(12), 3982. [CrossRef]

- U. Zakira, K. Zheng, N. Xie, B. Birgisson, Development of high-strength geopolymers from red mud and blast furnace slag, J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135439. [CrossRef]

- K. Tian, Y. Wang, B. Dong, G. Fang, F. Xing, Engineering and micro-properties of alkali-activated slag pastes with Bayer red mud, Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 351, 128869. [CrossRef]

- I.M. Nikbin, M. Aliaghazadeh, Sh Charkhtab, A. Fathollahpour, Environmental impacts and mechanical properties of lightweight concrete containing bauxite residue (red mud), J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2683–2694. [CrossRef]

- Z. Luo, M. Ge, L. Liu, X. Liu, W. Zhang, J. Ye, M. Gao, Y. Yang, M. Zhang, X. Liu, Desulfurization-modified red mud for supersulfated cement production: Insights into hydration kinetics, microstructure, and mechanical properties, Composites Part B: Engineering. 2025, 297, 112340. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tan, X. Zhang, Z. Liu, F. Wang, S. Hu, Dealkalization behavior and leaching mechanisms of red mud with simulated aluminum profile wastewater, Dev. Built Environ. 2025, 21, 100613. [CrossRef]

- X. Xi, K.A. Jin, X. Niu, S. Zhang, A novel tandem pyrolysis-catalytic upgrading strategy for plastic waste to high-value products with zeolite and red mud, Energy. 2025, 330, 136921. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, S. Jin, T. Yan, X. Qiao, J. Yuan, Unraveling the interactive effects of Na2O/Al2O3, SiO2/Al2O3 and calcium on the properties of geopolymers from circulating fluidized bed fly ashes, Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e3798. [CrossRef]

- M. Irfan Khan, K. Azizli, S. Sufian, Z. Man, Sodium silicate-free geopolymers as coating materials: Effects of Na/Al and water/solid ratios on adhesion strength, Ceram. 2015, 41 (2, Part B), 2794-2805. [CrossRef]

- B. Kim, J. Kang, Y. Shin, T. Yeo, J. Heo, W. Um, Effect of Si/Al molar ratio and curing temperatures on the immobilization of radioactive borate waste in metakaolin-based geopolymer waste form, J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131884. [CrossRef]

- L. Zheng, W. Wang, Y. Shi, The effects of alkaline dosage and Si/Al ratio on the immobilization of heavy metals in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash-based geopolymer, Chemosphere 2010, 79(6), 665-671. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, J. Zhang, Z. Lei, M. Gao, J. Sun, L. Tong, S. Chen, Y. Wang, Designing low-carbon fly ash based geopolymer with red mud and blast furnace slag wastes: Performance, microstructure and mechanism, J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 354, 120362. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, J. Doh, D.E.L. Ong, H.L. Dinh, Z. Podolsky, G. Zi, Investigation on red mud and fly ash-based geopolymer: Quantification of reactive aluminosilicate and derivation of effective Si/Al molar ratio, J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106559. [CrossRef]

- M. Rowles, B. O'Connor, Chemical optimisation of the compressive strength of aluminosilicate geopolymers synthesised by sodium silicate activation of metakaolinite, Journal of Materials Chemistry 2003, 13(5), 1161-1165. [CrossRef]

- G. Kim, S. Cho, S. Im, J. Yoon, H. Suh, M. Kanematsu, A. Machida, T. Shobu, S. Bae, Evaluation of the thermal stability of metakaolin-based geopolymers according to Si/Al ratio and sodium activator, Cement and Concrete Composites. 2024, 150, 105562. [CrossRef]

- K. Pimraksa, P. Chindaprasirt, A. Rungchet, K. Sagoe-Crentsil, T. Sato, Lightweight geopolymer made of highly porous siliceous materials with various Na2O/Al2O3 and SiO2/Al2O3 ratios, Materials Science and Engineering: A 2011, 528(21), 6616-6623. [CrossRef]

- P. Duxson, A. Fernández-Jiménez, J.L. Provis, G.C. Lukey, A. Palomo, J.S.J. van Deventer, Geopolymer technology: The current state of the art, J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42(9), 2917-2933. [CrossRef]

- F. Souayfan, E. Roziere, C. Justino, M. Paris, D. Deneele, A. Loukili, Comprehensive study on the reactivity and mechanical properties of alkali-activated metakaolin at high H2O/Na2O ratios, Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 231, 106758. [CrossRef]

- D. Khale, R. Chaudhary, Mechanism of geopolymerization and factors influencing its development: A review, J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42 (3), 729-746. [CrossRef]

- G. Saini, U. Vattipalli, Assessing properties of alkali activated GGBS based self-compacting geopolymer concrete using nano-silica, Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2020, 12, e352. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhou, Z. Geng, J. Shi, Enhanced passivity of reinforcing steel in cementitious materials with thermally-activated red mud, Cement and Concrete Composites. 2024, 153, 105696. [CrossRef]

- K. Kopecskó, M. Hajdu, A.A. Khalaf, I. Merta, Fresh and hardened properties for a wide range of geopolymer binders – an optimization process, Cleaner Engineering and Technology. 2024, 21, 100770. [CrossRef]

- R. Churata, J. Almirón, M. Vargas, D. Tupayachy-Quispe, J. Torres-Almirón, Y. Ortiz-Valdivia, F. Velasco, Study of geopolymer composites based on volcanic ash, fly ash, pozzolan, metakaolin and mining tailing, Buildings, 2022, 12(8), 1118. [CrossRef]

- H. El-Hassan, P. Kianmehr, D. Tavakoli, A. El-Mir, R.S. Dehkordi, Synergic effect of recycled aggregates, waste glass, and slag on the properties of pervious concrete, Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 15, 100189. [CrossRef]

- D. Hou, D. Wu, X. Wang, S. Gao, R. Yu, M. Li, P. Wang, Y. Wang, Sustainable use of red mud in ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC): Design and performance evaluation, Cement and Concrete Composites. 2021, 115, 103862. [CrossRef]

- Y.H. Emminger, L. Ladner, C. Ruiz-Agudo, Comparative study of the early stages of crystallization of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and calcium aluminate silicate hydrate (C-A-S-H), Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 193, 107873. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, Z. Niu, J. Wang, G.R. Zhu, M. Zhou, Effect of sodium polyacrylate on mechanical properties and microstructure of metakaolin-based geopolymer with different SiO2/Al2O3 ratio, Ceram. 2018, 44(15), 18173-18180. [CrossRef]

- J. Xie, J. Wang, R. Rao, C. Wang, C. Fang, Effects of combined usage of GGBS and fly ash on workability and mechanical properties of alkali activated geopolymer concrete with recycled aggregate, Composites Part B: Engineering. 2019, 164, 179–190. [CrossRef]

- T. Ai, D. Zhong, Y. Zhang, J. Zong, X. Yan, Y. Niu, The Effect of Red Mud Content on the Compressive Strength of Geopolymers under Different Curing Systems, Buildings, 2021, 11(7), 298. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yang, Z. Chen, H. Zhu, B. Zhang, Z. Dong, X. Zhan, Efficient utilization of coral waste for internal curing material to prepare eco-friendly marine geopolymer concrete, J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 368, 122173. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, C. Gao, H. Rong, S. Liu, Y. Shi, H. Wang, Q. Wang, X. Zhang, J. Han, K. Jing, H. Wu, X. Chen, K. Deng, The shrinkage and durability performance evaluations for concrete exposed to temperature variation environments at early-age, J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112457. [CrossRef]

- M. Feng, C. Jiang, Y. Wang, Y. Zou, J. Zhao, Experimental study on mechanical properties and drying shrinkage compensation of solidified Ultra-Fine dredged sand blocks made with GGBS-Based geopolymer, Buildings, 2023, 13(7), 1750. [CrossRef]

- W. Chen, H. Zhu, Y. Li, L. Yang, S. Cheng, H. Yu, Engineered cementitious composites using blended limestone calcined clay and fly ash: Mechanical properties and drying shrinkage modeling, Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e2960. [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, Z.Y. Yin, P.Y. Hicher, Y.J. Cui, Micro-mechanical analysis of one-dimensional compression of clay with dem. International Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics. 2023, 47. [CrossRef]

- A. Hajimohammadi, J.L. Provis, J.S.J. van Deventer, The effect of silica availability on the mechanism of geopolymerisation, Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41(3), 210-216. [CrossRef]

- M.P. Bilondi, M.A. Daluee, M. Amirriahi, M.A. Eslamieh, K. Rajaee, M. Zaresefat, Durability assessment of clay soils stabilised with geopolymers based on recycled glass powder in various corrosive environments, Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105691. [CrossRef]

- S.X. Song, P. Wang, Z.Y. Yin, Y. P. Cheng, Micromechanical modeling of hollow cylinder torsional shear test on sand using discrete element method. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering. 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhang, M. He, Z. Pan, Inhibition of efflorescence for fly ash-slag-steel slag based geopolymer: Pore network optimization and free alkali stabilization, Ceram. 2024, 50 (22, Part C), 48538-48550. [CrossRef]

- Z. Hu, M. Wyrzykowski, P. Lura, Estimation of reaction kinetics of geopolymers at early ages, Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 129, 105971. [CrossRef]

- A. Raza, A. Selmi, K.M. Elhadi, N. Ghazouani, W. Chen, Strength analysis and microstructural characterization of calcined red mud based-geopolymer concrete modified with slag and phosphogypsum, Journal of Materials Research and Technology. 2024, 33, 6168–6181. [CrossRef]

- T. Ai, D. Zhong, Y. Zhang, J. Zong, X. Yan, Y. Niu, The Effect of Red Mud Content on the Compressive Strength of Geopolymers under Different Curing Systems. Buildings, 2021, 11(7), 298. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Gaifutdinov, K.A. Andrianova, L.M. Amirova, R.R. Amirov, Optimizing the manufacturing technology of high-strength fiber reinforced composites based on aluminophosphates, Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing. 2024, 185, 108310. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, M. Gao, Z. Lei, L. Tong, J. Sun, Y. Wang, X. Wang, X. Jiang, Ternary cementless composite based on red mud, ultra-fine fly ash, and GGBS: Synergistic utilization and geopolymerization mechanism, Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e2410. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, C. Zou, C.L. Yong, R.J.S. Jan, T.H. Tan, J. Lin, K.H. Mo, Utilization of waste glass as precursor material in one-part alkali-activated aggregates, Journal of Materials Research and Technology. 2024, 33, 5551–5558. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yang, R. Li, H. Zhu, B. Zhang, Z. Dong, X. Zhan, G. Zhang, H. Zhang, Synthesis of eco-sustainable seawater sea-sand geopolymer mortars from ternary solid waste: Influence of microstructure evolution on mechanical performance, Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 41, e1056. [CrossRef]

- R. Cioffi, L. Maffucci, L. Santoro, Optimization of geopolymer synthesis by calcination and polycondensation of a kaolinitic residue, Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2003, 40(1), 27-38. [CrossRef]

- L.M. Costa, T.D.C.C. Souza, R.K.F.G. Oliveira, N.G.S. Almeida, M. Houmard, Effects of silicas and aluminosilicate synthesized by sol-gel process on the structural properties of metakaolin-based geopolymers, Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 267, 107743. [CrossRef]

- K. Chen, W. Lin, Q. Liu, B. Chen, V.W.Y. Tam, Micro-characterizations and geopolymerization mechanism of ternary cementless composite with reactive ultra-fine fly ash, red mud and recycled powder, Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 343, 128091. [CrossRef]

- B. Lyu, L. Guo, X. Fei, J. Wu, R. Bian, Preparation and properties of green high ductility geopolymer composites incorporating recycled fine brick aggregate, Cement and Concrete Composites. 2023, 139, 105054. [CrossRef]

- M. He, Z. Yang, N. Li, X. Zhu, B. Fu, Z. Ou, Strength, microstructure, CO2 emission and economic analyses of low concentration phosphoric acid-activated fly ash geopolymer, Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 374, 130920. [CrossRef]

- L. Qin, X.J. Gao, Q.Y. Li, Upcycling carbon dioxide to improve mechanical strength of portland cement. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Bahmani, H. Mostafaei, P. Santos, N. Fallah Chamasemani, Enhancing the mechanical properties of Ultra-High-Performance concrete (UHPC) through silica sand replacement with steel slag, Buildings, 2024, 14(11), 3520. [CrossRef]

- Z. Sun, Q. Tang, B.S. Xakalashe, X. Fan, M. Gan, X. Chen, Z. Ji, X. Huang, B. Friedrich, Mechanical and environmental characteristics of red mud geopolymers, Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 321, 125564. [CrossRef]

- A. Bayat, A. Hassani, O. And Azami, Thermo- mechanical properties of alkali-activated slag–Red mud concrete, Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2020, 21 (2), 411-433. [CrossRef]

- A. Bayat, A. Hassani, A.A. Yousefi, Effects of red mud on the properties of fresh and hardened alkali-activated slag paste and mortar, Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 775–790. [CrossRef]

| Raw material | Al2O3 | SiO2 | CaO | Na2O | Fe2O3 | TiO2 | Others | LOI |

| RM | 25.11 | 16.93 | 6.02 | 11.60 | 36.43 | 1.54 | 1.70 | - |

| GGBS | 13.70 | 31.10 | 40.90 | 0.38 | 0.65 | 1.26 | 2.85 | 0.96 |

| No. | Precursors | Activators a | SiO2/Al2O3 | Na2O/Al2O3 | H2O/Na2O | Water a | Remarks | ||

| RM | GGBS | NaOH | Na2O·nSiO2 | ||||||

| Si300 | 36 | 64 | 0.035 | 0.074 | 3.00 | 0.85 | 17.24 | 0.363 | Group 1 |

| Si275 | 43 | 57 | 0.032 | 0.069 | 2.75 | 0.85 | 17.24 | 0.390 | |

| Si256 | 50 | 50 | 0.026 | 0.072 | 2.56 | 0.85 | 17.24 | 0.406 | |

| Si225 | 56 | 44 | 0.031 | 0.048 | 2.25 | 0.85 | 17.24 | 0.457 | |

| GBS50 | 50 | 50 | 0.026 | 0.072 | 2.56 | 0.85 | 17.24 | 0.406 | Group 2 |

| GBS54 | 46 | 54 | 0.029 | 0.080 | 2.72 | 0.87 | 17.24 | 0.395 | |

| GBS58 | 42 | 58 | 0.032 | 0.088 | 2.90 | 0.89 | 17.24 | 0.385 | |

| GBS63 | 37 | 63 | 0.035 | 0.098 | 3.12 | 0.92 | 17.24 | 0.372 | |

| Material type | CO2 emissions | Cost a |

| (kg CO2•eq/kg) | (CNY/kg) | |

| RM [59,64] | 0.303 | 0.22 |

| GGBS [59,65] | 0.067 | 0.5 |

| NaOH [59,65] | 3.2 | 7.53 |

| Na2O·nSiO2 b [59,66] | 0.4 | 4.67 |

| Water c [67] | 0 | 0.0083 |

| type | Mixtures in references | Mixtures in this study | |||||

| [69] | [70] | [71] | Si225 | Si256 | Si275 | Si300 | |

| RM (kg/m3) | 714.05 | 519.56 | 471.05 | 613.00 | 551.40 | 484.83 | 413.31 |

| GGBS (kg/m3) | 714.05 | 779.35 | 706.57 | 481.64 | 551.40 | 642.68 | 734.78 |

| NaOH (kg/m3) | 95.25 | 58.45 | 52.99 | 33.93 | 28.67 | 36.08 | 40.18 |

| Na2O·nSiO2 (kg/m3) | 48.41 | 55.20 | 101.28 | 52.54 | 79.40 | 77.80 | 84.96 |

| Water (kg/m3) | 428.43 | 487.09 | 500.49 | 569.21 | 551.40 | 541.21 | 528.12 |

| CO2 emissions (kg/m3) | 588.38 | 418.77 | 400.16 | 347.62 | 327.53 | 336.54 | 337.03 |

| Cost (CNY/kg) | 1461.03 | 1205.96 | 1333.07 | 881.30 | 988.30 | 1019.21 | 1162.04 |

| Compressive strength (28, MPa) | 36 | 34 | 37 | 30.1 | 32.8 | 34.5 | 37.5 |

| CO2 intensity (kg/m3/MPa) | 16.34 | 12.32 | 10.82 | 11.55 | 9.99 | 9.75 | 8.99 |

| Cost intensity (CNY/m3/MPa) | 40.58 | 35.47 | 36.03 | 29.28 | 30.13 | 29.54 | 30.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).