Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

Purpose

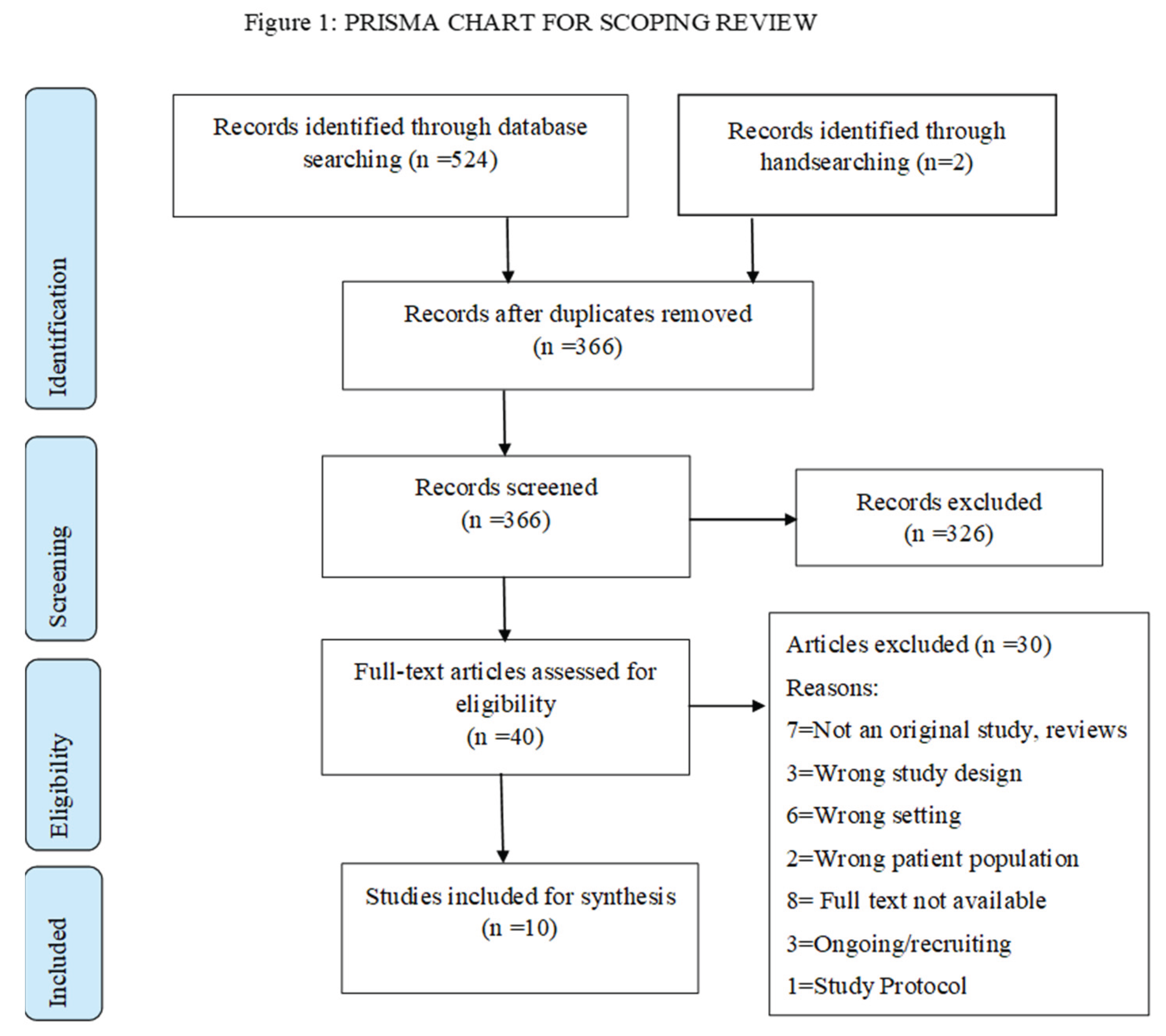

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Primary studies of quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods, reporting on any type of psychosocial intervention in ICU patients.

- Studies involving interventions for adult intensive or critical care patients while still hospitalized in critical/ intensive care unit, regardless of their primary diagnoses and type of unit.

- Peer-reviewed studies published since 2009, since the context of care was different prior to publication of clinical practice guidelines regarding pain agitation and delirium in the ICU.

- Case studies, literature reviews, opinion pieces, editorials, research protocols

- Intervention(s) for family members only, not involving ICU patients

- Patients under 18 years of age such as neonates, infants, children, paediatric patients.

- Articles in any language other than English.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Screeningand Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Quality Appraisal of Included Studies

3.3. Types of Interventions

3.3.1. Psychological Well-Being Outcomes

3.3.2. Other Clinical Outcomes

3.3.3. Feasibility and Acceptability

4. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Search Strategy (OVID/MEDLINE)

| SN | Searches | Results |

| 1 | (("Intensive care" or "critical care") adj3 (unit* or ward* or floor* or nurs*)).mp. | 530360 |

| 2 | "critical* ill*".mp. | 202608 |

| 3 | ICU.ti,ab. | 241335 |

| 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 | 718543 |

| 5 | patient*.mp. | 21576739 |

| 6 | (((Psychological* or mental* or emotion*) adj3 (stress or distress or pressure or strain or tension)) or anxiet* or anxiousness or worry or worrie* or nervous*).mp. | 3215392 |

| 7 | (((Psychosocial or spiritual* or religious or religion) adj3 (intervention* or support*)) or counsel* or "positive suggestion*" or "positive messag*" or mindfulness or meditat*).mp. | 687587 |

| 8 | 4 and 5 and 6 and 7 | 626 |

| 9 | (neonat* or p?ediatric* or child* or infant*).mp. | 8285783 |

| 10 | 8 not 9 | 444 |

| 11 | remove duplicates from 10 | 334 |

| 12 | 11 and 2009:2023.(sa_year). | 232 |

References

- Gil-Juliá, B. Ferrándiz-Sellés, M. D., Giménez-García, C., Castro-Calvo, J., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2020). Psychological distress in critically ill patients: risk and protective factors. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 25(2), 81. [CrossRef]

- Kusi-Appiah, E. Karanikola, M., Pant, U., Meghani, S., Kennedy, M., & Papathanassoglou, E. (2025). Disempowered Warriors: Insights on Psychological Responses of ICU Patients Through a Meta-Ethnography. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 13(8), 894.

- Krampe, H. Denke, C., Gülden, J., Mauersberger, V.-M., Ehlen, L., Schönthaler, E., Wunderlich, M. M., Lütz, A., Balzer, F., Weiss, B., & Spies, C. D. (2021). Perceived severity of stressors in the intensive care unit: a systematic review and semi-quantitative analysis of the literature on the perspectives of patients, health care providers and relatives. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(17), 3928. [CrossRef]

- Boehm, L. M. Jones, A. C., Selim, A. A., Virdun, C., Garrard, C. F., Walden, R. L., Wesley Ely, E., & Hosie, A. (2021). Delirium-related distress in the ICU: a qualitative meta-synthesis of patient and family perspectives and experiences. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 122, 104030. [CrossRef]

- Gezginci, E., Goktas, S., & Orhan, B. N. (2020). The effects of environmental stressors in intensive care unit on anxiety and depression. Nursing in Critical Care, 27(1), 113–119. [CrossRef]

- Shdaifat, S. A., & Al Qadire, M. (2020). Anxiety and depression among patients admitted to intensive care. Nursing in Critical Care, 27(1), 106–112. [CrossRef]

- Kornienko, A. (2021). Intensive care unit environment and sleep. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 33(2), 121–129. [CrossRef]

- Medrzycka-Dabrowska, W. Lewandowska, K., Kwiecień-Jaguś, K., & Czyż-Szypenbajl, K. (2018). Sleep deprivation in intensive care unit – systematic review. Open Medicine, 13(1), 384–393. [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, J. M. & Singer, M. (2012). The stress response and critical illness: a review. Critical care medicine, 40(12), 3283–3289. [CrossRef]

- Mazeraud, A. Polito, A., Sivanandamoorthy, S., Porcher, R., Heming, N., Stoclin, A., Hissem, T., Antona, M., Blot, F., Gaillard, R., Chrétien, F., Annane, D., Bozza, F. A. B., Siami, S., Sharshar, T., & Groupe d’Explorations Neurologiques en Réanimation (GENER) (2020). Association Between Anxiety and New Organ Failure, Independently of Critical Illness Severity and Respiratory Status: A Prospective Multicentric Cohort Study. Critical care medicine, 48(10), 1471–1479. [CrossRef]

- Papathanassoglou, E. D. Giannakopoulou, M., Mpouzika, M., Bozas, E., & Karabinis, A. (2010). Potential effects of stress in critical illness through the role of stress neuropeptides. Nursing in critical care, 15(4), 204-216.

- Wernerman, J. Christopher, K. B., Annane, D., Casaer, M. P., Coopersmith, C. M., Deane, A. M., De Waele, E., Elke, G., Ichai, C., Karvellas, C. J., McClave, S. A., Oudemans-van Straaten, H. M., Rooyackers, O., Stapleton, R. D., Takala, J., van Zanten, A. R. H., Wischmeyer, P. E., Preiser, J. C., & Vincent, J. L. (2019). Metabolic support in the critically ill: a consensus of 19. Critical care (London, England), 23(1), 318. [CrossRef]

- Prescott, H. C. & Costa, D. K. (2018). Improving Long-Term Outcomes After Sepsis. Critical care clinics, 34(1), 175–188. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M. I. Cooke, M., Macfarlane, B., & Aitken, L. M. (2016). Factors associated with anxiety in critically ill patients: A prospective observational cohort study. International journal of nursing studies, 60, 225–233. [CrossRef]

- Oberoi, V. Sekhon, A., & Sarangi, A. (2024). Management of post-extubation anxiety in the intensive care unit. The Southwest Respiratory and Critical Care Chronicles. [CrossRef]

- Orvelius, L. Teixeira-Pinto, A., Lobo, C., Costa-Pereira, A., & Granja, C. (2016). The role of memories on health-related quality of life after Intensive Care Unit Care: An unforgettable controversy? Patient Related Outcome Measures, 7, 63. [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, Y., Unoki, T., Sakuramoto, H., Ouchi, A., Hoshino, H., Matsuishi, Y., & Mizutani, T. (2021). Association between intensive care unit delirium and delusional memory after critical care in mechanically ventilated patients. Nursing Open, 8(3), 1436–1443. [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, E., Stroud, L., Sharp, G., Van Vuuren, N., Mosola, M., Fodo, T., & Paruk, F. (2024). Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder 6 weeks and 6 months after ICU: Six out of 10 survivors affected. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde, 114(7), e1988. [CrossRef]

- Gravante, F., Trotta, F., Latina, S., Simeone, S., Alvaro, R., Vellone, E., & Pucciarelli, G. (2024). Quality of life in ICU survivors and their relatives with post-intensive care syndrome: A systematic review. Nursing in critical care, 29(4), 807–823. [CrossRef]

- Lavolpe, S. Beretta, N., Bonaldi, S., Tronci, S., Albano, G., Bombardieri, E., & Merlo, P. (2024). Medium- and Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 in a Population of Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: Cognitive and Psychological Sequelae and Quality of Life Six Months and One Year after Discharge. Healthcare, 12. [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, M. Safaei, A., Sadat, Z., Abbasi, P., Sarcheshmeh, M. S., Dehghani, F., Tahrekhani, M., & Abdi, M. (2021). Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among patients discharged from critical care units. Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 7(2), 113–122. [CrossRef]

- Sareen, J. Olafson, K., Kredentser, M. S., Bienvenu, O. J., Blouw, M., Bolton, J. M., Logsetty, S., Chateau, D., Nie, Y., Bernstein, C. N., Afifi, T. O., Stein, M. B., Leslie, W. D., Katz, L. Y., Mota, N., El-Gabalawy, R., Sweatman, S., & Marrie, R. A. (2020). The 5-year incidence of mental disorders in a population-based ICU survivor cohort. Critical Care Medicine, 48(8). [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, A.-F. Prescott, H. C., Brett, S. J., Weiss, B., Azoulay, E., Creteur, J., Latronico, N., Hough, C. L., Weber-Carstens, S., Vincent, J.-L., & Preiser, J.-C. (2021). Long-term outcomes after critical illness: recent insights. Critical Care, 25(1). [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, D. Fujitani, S., Morimoto, T., Dote, H., Takita, M., Takaba, A., Hino, M., Nakamura, M., Irie, H., Adachi, T., Shibata, M., Kataoka, J., Korenaga, A., Yamashita, T., Okazaki, T., Okumura, M., & Tsunemitsu, T. (2021). Prevalence of post-intensive care syndrome among Japanese intensive care unit patients: a prospective, multicenter, observational J-PICS study. Critical care (London, England), 25(1), 69. [CrossRef]

- Marra, A. Pandharipande, P. P., Girard, T. D., Patel, M. B., Hughes, C. G., Jackson, J. C., Thompson, J. L., Chandrasekhar, R., Ely, E. W., & Brummel, N. E. (2018). Co-occurrence of post-intensive care syndrome problems among 406 survivors of critical illness*. Critical Care Medicine, 46(9), 1393–1401. [CrossRef]

- Heydon, E. Wibrow, B., Jacques, A., Sonawane, R., & Anstey, M. (2020). The needs of patients with post–intensive care syndrome: a prospective, observational study. Australian Critical Care, 33(2), 116–122. [CrossRef]

- Pant, U. Vyas, K., Meghani, S., Park, T., Norris, C. M., & Papathanassoglou, E. (2022). Screening tools for post-intensive care syndrome and post-traumatic symptoms in intensive care unit survivors: A scoping review. Australian critical care : official journal of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses, S1036-7314(22)00199-0. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- England, M. J. Butler, A. S., & Gonzalez, M. L. (2015). Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards.

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Khalil, H., Larsen, P., Marnie, C., Pollock, D., Tricco, A. C., & Munn, Z. (2022). Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI evidence synthesis, 20(4), 953–968. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C. Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of internal medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Checklist for quantitative studies (2012) https://www.nice.org.

- Bannon, S. Lester, E. G., Gates, M. V., McCurley, J., Lin, A., Rosand, J., & Vranceanu, A. M. (2020). Recovering together: building resiliency in dyads of stroke patients and their caregivers at risk for chronic emotional distress; a feasibility study. Pilot and feasibility studies, 6, 75. [CrossRef]

- Berning, J. N., Poor, A. D., Buckley, S. M., Patel, K. R., Lederer, D. J., Goldstein, N. E., Brodie, D., & Baldwin, M. R. (2016). A Novel Picture Guide to Improve Spiritual Care and Reduce Anxiety in Mechanically Ventilated Adults in the Intensive Care Unit. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 13(8), 1333–1342.

- Karnatovskaia, L. V., Schultz, J. M., Niven, A. S., Steele, A. J., Baker, B. A., Philbrick, K. L., Del Valle, K. T., Johnson, K. R., Gajic, O., & Varga, K. (2021). System of Psychological Support Based on Positive Suggestions to the Critically Ill Using ICU Doulas. Critical care explorations, 3(4), e0403.

- Tan, Y., Gajic, O., Schulte, P. J., Clark, M. M., Philbrick, K. L., & Karnatovskaia, L. V. (2020). Feasibility of a Behavioral Intervention to Reduce Psychological Distress in Mechanically Ventilated Patients. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 68(4), 419–432. [CrossRef]

- Ong, T. L. Ruppert, M. M., Akbar, M., Rashidi, P., Ozrazgat-Baslanti, T., Bihorac, A., & Suvajdzic, M. (2020). Improving the Intensive Care Patient Experience With Virtual Reality-A Feasibility Study. Critical care explorations, 2(6), e0122. [CrossRef]

- Elham, H. Hazrati, M., Momennasab, M., & Sareh, K. (2015). The effect of need-based spiritual/religious intervention on spiritual well-being and anxiety of elderly people. Holistic nursing practice, 29(3), 136–143. [CrossRef]

- K Szilágyi, A. Diószeghy, C., Fritúz, G., Gál, J., & Varga, K. (2014). Shortening the length of stay and mechanical ventilation time by using positive suggestions via MP3 players for ventilated patients. Interventional medicine & applied science, 6(1), 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, C. Stotz, U., Burbaum, C., Feuchtinger, J., Leonhart, R., Siepe, M., Beyersdorf, F., & Fritzsche, K. (2016). Short-term intervention to reduce anxiety before coronary artery bypass surgery--a randomised controlled trial. Journal of clinical nursing, 25(3-4), 351–361. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Yang, X., Kumar, P., Cao, B., Ma, X., & Li, T. (2020). Social support and clinical improvement in COVID-19 positive patients in China. Nursing outlook, 68(6), 830–837. [CrossRef]

- Wade, D. Als, N., Bell, V., Brewin, C., D'Antoni, D., Harrison, D. A., Harvey, M., Harvey, S., Howell, D., Mouncey, P. R., Mythen, M., Richards-Belle, A., Smyth, D., Weinman, J., Welch, J., Whitman, C., Rowan, K. M., & POPPI investigators (2018). Providing psychological support to people in intensive care: development and feasibility study of a nurse-led intervention to prevent acute stress and long-term morbidity. BMJ open, 8(7), e021083. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J. W. Skrobik, Y., Gélinas, C., Needham, D. M., Slooter, A. J. C., Pandharipande, P. P., Watson, P. L., Weinhouse, G. L., Nunnally, M. E., Rochwerg, B., Balas, M. C., van den Boogaard, M., Bosma, K. J., Brummel, N. E., Chanques, G., Denehy, L., Drouot, X., Fraser, G. L., Harris, J. E., Joffe, A. M., … Alhazzani, W. (2018). Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Critical care medicine, 46(9), e825–e873. [CrossRef]

- Kekecs, Z. Nagy, T., & Varga, K. (2014). The effectiveness of suggestive techniques in reducing postoperative side effects: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesia and analgesia, 119(6), 1407–1419. [CrossRef]

- DuBois, C. M. Lopez, O. V., Beale, E. E., Healy, B. C., Boehm, J. K., & Huffman, J. C. (2015). Relationships between positive psychological constructs and health outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. International journal of cardiology, 195, 265–280. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J. Q. Nguyen, C. D., Lopes, R., Ezeji-Okoye, S. C., & Kuschner, W. G. (2018). Spiritual Care in the Intensive Care Unit: A Narrative Review. Journal of intensive care medicine, 33(5), 279–287. [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C. (2004). Spirituality in health: the role of spirituality in critical care. Critical care clinics, 20(3), 487–x. [CrossRef]

- Weiland S., A. (2010). Integrating spirituality into critical care: an APN perspective using Roy's adaptation model. Critical care nursing quarterly, 33(3), 282–291. [CrossRef]

- Aslakson, R. A. Kweku, J., Kinnison, M., Singh, S., Crowe, T. Y., 2nd, & AAHPM Writing Group (2017). Operationalizing the Measuring What Matters Spirituality Quality Metric in a Population of Hospitalized, Critically Ill Patients and Their Family Members. Journal of pain and symptom management, 53(3), 650–655. [CrossRef]

- Willemse, S., Smeets, W., van Leeuwen, E., Nielen-Rosier, T., Janssen, L., & Foudraine, N. (2020). Spiritual care in the intensive care unit: An integrative literature research. Journal of critical care, 57, 55–78. [CrossRef]

- Badanta, B. Rivilla-García, E., Lucchetti, G., & de Diego-Cordero, R. (2022). The influence of spirituality and religion on critical care nursing: An integrative review. Nursing in critical care, 27(3), 348–366. [CrossRef]

- Aristidou, M. Karanikola, M., Kusi-Appiah, E., Koutroubas, A., Pant, U., Vouzavali, F.,... & Papathanassoglou, E. (2023). The living experience of surviving out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and spiritual meaning making. Nursing open, 10(8), 5282-5292.

- Gordon, B. S. Keogh, M., Davidson, Z., Griffiths, S., Sharma, V., Marin, D., Mayer, S. A., & Dangayach, N. S. (2018). Addressing spirituality during critical illness: A review of current literature. Journal of critical care, 45, 76–81. [CrossRef]

- Choi, P. J. Curlin, F. A., & Cox, C. E. (2019). Addressing religion and spirituality in the intensive care unit: A survey of clinicians. Palliative & supportive care, 17(2), 159–164. [CrossRef]

- 54. Qin, D., Du, W., Sha, S., Parkinson, A., & Glasgow, N. (2019). Hospital psychosocial interventions for patients with brain functional impairment: A retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(5), 1152-1161–1161. https://doi-org.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/10.1111/inm.12627.

- Smith, T. B. Workman, C., Andrews, C., Barton, B., Cook, M., Layton, R., Morrey, A., Petersen, D., & Holt-Lunstad, J. (2021). Effects of psychosocial support interventions on survival in inpatient and outpatient healthcare settings: A meta-analysis of 106 randomized controlled trials.

- Ponsford, J., Lee, N. K., Wong, D. et al. (2016) Efficacy of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression symptoms following traumatic brain injury. Psychological Medicine, 46(5), 1079–1090.

- Warth, M., Kessler, J., Koehler, F., Aguilar-Raab, C., Bardenheuer, H. J., & Ditzen, B. (2019). Brief psychosocial interventions improve quality of life of patients receiving palliative care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PALLIATIVE MEDICINE, 33(3), 332–345. https://doi-org.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/10.1177/0269216318818011.

- Kekecs, Z. & Varga, K. (2013). Positive suggestion techniques in somatic medicine: A review of the empirical studies. Interventional medicine & applied science, 5(3), 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Schlanger, J., Fritúz, G., & Varga, K. (2013). Therapeutic suggestion helps to cut back on drug intake for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care unit. Interventional medicine & applied science, 5(4), 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Szilágyi, A. K., Dioszeghy, C., Benczúr, L., & Varga, K. (2007). Effectiveness of psychological support based on positive suggestion with the ventilated patient. European Journal of Mental Health, 2(2), 147–170. [CrossRef]

- Varga, K. Varga, Z., & Fritúz, G. (2013). Psychological support based on positive suggestions in the treatment of a critically ill ICU patient - A case report. Interventional medicine & applied science, 5(4), 153–161. [CrossRef]

- Marra, A. Ely, E. W., Pandharipande, P. P., & Patel, M. B. (2017). The ABCDEF bundle in critical care. Critical care clinics, 33(2), 225-243.

- Canadian Association of Critical Care Nursing. Standards for Critical Care Nursing Practice (2017) (5th Edition). Retrived from https://caccn.ca/publications/standards-for-critical-care-nursing-practice/.

- American Association of Critical Care Nursing. AACN Scope and Standards for Progressive and Critical Care Nursing Practice (2019) Retrieved from https://www.aacn.

- Critical Care Networks Nurse Leads group - CC3N (2015) National Competency Framework for Adult Critical Care Nurses. Available at: http://www.cc3n.org.uk/competencyframework/4577977310.

- Davidson, J. E. Powers, K., Hedayat, K. M., Tieszen, M., Kon, A. A., Shepard, E., Spuhler, V., Todres, I. D., Levy, M., Barr, J., Ghandi, R., Hirsch, G., Armstrong, D., & American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005, Society of Critical Care Medicine (2007). Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Critical care medicine, 35(2), 605–622. [CrossRef]

- European federation of Critical Care Nursing associations (EfCCNa), Competencies for European Critical Care Nurses (2013) https://www.efccna.org/images/stories/publication/competencies_cc.pdf?

| Author (year, country) | Study Design | Aim of the study | Sample size and patient characteristics | Intervention details (delivery, length, frequency, duration) | Outcome variables and measurement tools | Analysis tools | Main findings | Study conclusions |

| Bannon et al. (2020, United States) [32] | RCT | “Measure feasibility and acceptability markers (primary outcomes) include ability to recruit and retain dyads, acceptability of randomization, credibility, and satisfaction.” |

Target population: Stroke patients and their caregivers (dyads) with at least one person (patient or caregiver) at risk of chronic emotional distress # of participants: 16 dyads from a neuro-ICU. 7 allocated to receive RT intervention; 9 allocated to receive MEUC. Mean age: Patients- 53.9 (± 17.4) years. Caregivers- 48.88 (± 10.62) years. Gender: Patients- 9 (56.3%) female. Caregivers- 12 (75.0%) female. Race: Patients- 14 (87.5%) White; 2 (12.5%) Asian. Caregivers- 13 (81.3%) White; 2 (12.5%) Asian; 1 (6.3%) identified as more than one race. |

Type of intervention: Dyadic intervention Intervention provided by: Unspecified clinician Specific approaches: RT intervention included elements of cognitive behavioural therapy, dialectical behavioural therapy, and trauma-informed care. Sessions covered deep breathing, meditation, self-care, stress management techniques, effective communication skills and the ability to manage change, and developing and adhering to new habits. Length: 20-30 minutes Frequency: 6 sessions Duration: From baseline (pre-test) to 6 weeks later (post-test) |

Outcome variables: Depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress (PTS) Measurement tools: Hospital Depression and Anxiety Scale (HADS-D, HADS-A), PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C), General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE), Measure of Current Status Part A (MOCS-A), Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS), and Intimate Bond Measure (IBM). Others included Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQS) and the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-3). CSQ-3 was measured at post-test. |

Cohen’s d for effect size | Participants receiving RT showed a decrease in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTS in patients (d = -0.41, -1.25, -0.83, respectively) and caregivers (d = -.63, -0.81, -0.98, respectively) from baseline to post-test. Participants who received only MEUC showed clinically significant increases in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTS in patients (d = 0.98, 0.44, 0.68, respectively) and in caregivers (d = 0.71, 0.48, 0.46, respectively). Resiliency variables (e.g., self-efficacy, mindfulness, perceived coping) showed small to large effect sizes (d = 0.07-0.85) in those who received the intervention but not in the control group from baseline to post-test. |

There is “promising evidence” that the RT intervention is a feasible and acceptable program for emotional distress in stroke patients and their caregivers when compared with MEUC. |

| Berning et al. (2016, United States) [33] | Quasi-experimental | “To determine the feasibility and measure the effects of chaplain-led picture-guided spiritual care for mechanically ventilated adults in the ICU.” |

Target population: “Mechanically ventilated adults in medical or surgical ICUs without delirium or dementia” # of participants: 50 patients in total. No control group identified in this study. Mean age: 59 (± 16) years Gender: 28 (56%) male Race: 25 (50%) White, 12 (24%) Hispanic, 9 (18%) Black, 4 (8%) Southeast Asian |

Type of intervention: Picture-guided spiritual care intervention Intervention provided by: Medical intensive care unit (MICU) chaplain Specific approaches: Spiritual care, in English or Spanish, that included illustrated communication cards to assess spiritual affiliation, emotions, and needs (including spiritual pain and a desired religious, spiritual, or nonspiritual intervention that a chaplain could provide). Length: 8.5 (5-13) minutes to complete four sections of communication card and 18 (11-25) minutes for chaplain to use the card and provide a specific spiritual intervention. Intervention lasted less than 25 minutes. Frequency: Not reported Duration: Not reported |

Outcome variables: Anxiety, stress Measurement tools: 100-mm Visual Analog Scales (VAS) |

Wilcoxon signed-rank test |

Pre-test vs. post-test: Mean VAS score = 64 (± 29) Vs 44 (± 28) (absolute reduction, P=0.002; relative reduction, P=0.001). Mean score change by 31%, -20; 95% CI, -33 to -7. Follow up (n=18) reported mean 49-point reduction in stress (95% CI, -72 to -24, P=0.002). Qualitative comments: “81% reported that they felt more capable of dealing with their hospitalization, 81% felt more at peace, 71% felt more connected with what is sacred, 96% would recommend chaplain-led picture-guided spiritual care to others, and 0% felt worse after receiving spiritual care.” |

“Chaplain-led picture-guided spiritual care is feasible among mechanically ventilated adults and shows potential for reducing anxiety during and stress after an ICU admission.” |

| Elham et al. (2015, Iran) [37] | Quasi-experimental | “To investigate the effects of a need-based spiritual/religious intervention on spiritual well-being (SWB) and anxiety of the elderly admitted to the coronary care unit (CCU) of Imam Reza Hospital in Lar, southern Iran.” |

Target population: Elderly patients admitted to the CCU # of participants: 66 patients in total with 33 patients each in the intervention group and control group Mean age: 68.86 (± 8.3) years Gender: 39 male, 27 females Race: Not reported |

Type of intervention: Spiritual- and religious-based intervention Intervention provided by: Researcher Specific approaches: Interventions included caring presence for 30 minutes, giving hope, encouraging generosity, strengthening personal relationships, providing them with opportunities for worship and prayer, assisting them for performing religious obligations such as ablution, hanging pictures of natural and relaxing landscapes on the walls of the ward, giving them Holy Quran and prayer books, providing them with Walkman audio players for listening to relaxing music, prayers, and Quran verses, and facilitating the patients’ visits with their family members and friends. The patients were also given small booklets prepared by the researcher that contained words of hope, generosity, and forgiveness from religious scholars. Length: 60-90 minutes Frequency: Every evening Duration: At least 3 consecutive days |

Outcome variables: SWB, anxiety Measurement tools: Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (S-Anxiety, T-Anxiety), Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) |

Independent and paired t tests, Pearson correlation coefficient, chi-square test, and repeated-measures of analysis of variance |

Post-test (Intervention): SWB scores= 79.03 (± 10.95) vs 83.33 (± 9.43) (P=0.001) S-Anxiety scores= 58 vs 49 (p<0.001). Post-test (control): SWB scores= 80.06 (± 10.36) VS 81.03 (± 8.72) S-Anxiety scores=59 VS 58.5 Statistics: No significant difference was found between the 2 groups (intervention vs control) before and after the intervention for SWB scores (P = .049). Significant difference between intervention and control group for S-anxiety and T-anxiety (P < .001). |

Individuals with strong religious beliefs and/or spiritual coping strategies have high SWB. This study’s findings demonstrate a negative correlation between SWB and anxiety, and that a spiritual/religious intervention may work to increase SWB in older CCU patients. |

| Heilmann et al. (2016, Germany) [39] | RCT | “To evaluate an intervention with individualized information and emotional support before coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in a controlled randomized trial.” |

Target population: Patients scheduled for CABG # of participants: 253 CABG patients in total with 139 in the intervention group and 114 in the control group Mean age: 68 (± 10) years Gender: 208 (82.2%) male, 45 (17.8%) female Race: 238 (94.1%) participants of German nationality, 15 (5.9%) participants of other unspecified nationalities |

Type of intervention: Psychotherapeutic intervention that consisted of a dialogue with additional information regarding surgery, postoperative care, and emotional support. Intervention provided by: Trained nurse Specific approaches: Intervention included an open dialogue; a short relaxation exercise; acceptance of denied negative emotions; reinforcement of the patient’s confidence in the medical team and a positive surgery outcome; differentiation between patients demonstrating vigilance or cognitive avoidance; providing information about postoperative care, pain management, and ICU stay; and promoting emotional expression. Length: 30 minutes Frequency: Once Duration: One day prior to CABG |

Outcome variable: Anxiety Measurement tools: State-Trait Operation Anxiety (STOA-S, STOA-T), Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Evaluation timeline: T0- after giving informed consent and before randomization, T1- in the evening after the intervention, and T2- on postoperative day 5 |

Multivariate analysis of variance, ANOVAs for continuous variables, chi-square tests for categorical variables |

Intervention group: T0- Affective anxiety: M=10.19 (± 3.90). Cognitive anxiety: M=10.47 (± 3.57). VAS: M=3.53 (± 2.88). Trait anxiety: M=33.03 (± 8.35). T1- Affective anxiety: M=9.10 (± 3.34). Cognitive anxiety: M=9.09 (± 3.19). VAS: M=2.86 (± 2.50). Trait anxiety: Not reported. T2- Affective anxiety: M=7.97 (± 2.68). Cognitive anxiety: M=8.69 (± 2.82). VAS: M=1.01 (± 1.65). Trait anxiety: M=33.03 (± 8.35) Control group: T0- Affective anxiety: M=10.40 (± 3.48). Cognitive anxiety: M=11.26 (± 3.53). VAS: M=3.62 (± 2.81). Trait anxiety: M=35.19 (± 9.31). T1- Affective anxiety: M=10.08 (± 3.43). Cognitive anxiety: M=10.38 (± 3.47). VAS: M=3.39 (± 2.69). Trait anxiety: Not reported. T2- Affective anxiety: M=8.35 (± 3.34). Cognitive anxiety: M=9.29 (± 4.00). VAS: M=1.51 (± 2 1.88). Trait anxiety: Not reported. Statistics: Decreases in affective (F [1,299] = 14.284, p < 0.001) and cognitive anxiety (F [1,299] = 17.457, p < 0.001) in the intervention group were statistically significant (P<0.001), as were reductions in intervention VAS scores (F [1,299] = 12.207, p < 0.001). |

This particular intervention is effective at reducing pre- and postoperative anxiety in CABG patients, as opposed to providing them with routine information alone. |

| Karnatovskaia et al. (2021, United States) [34] | Quasi-experimental | “To train and implement a PSBPS program for the critically ill using doulas, and measure acceptance of this intervention through stakeholder feedback.” |

Target population: ICU patients # of participants: 43 critically ill patients in the intervention group. No control group identified in this study. Mean age: Median age of participants 67 (58-74) years Gender: 58% male Race: Not reported |

Type of intervention: In-hospital, PSBPS intervention Intervention provided by: Two trained ICU doulas with combined 15 years of experience Specific approaches: Doulas were administered a PSBPS training program that included a detailed orientation to the ICU; instruction on unit protocols, safety, infection control, and hygiene through online modules; instruction on using an online medical reference. They also received classroom instruction on suggestion training through recorded presentations. Doulas then role played with PSBPS and later applied it to patients in the ICU. A reviewer watched and evaluated their PSBPS skills before and after training. Qualitative stakeholder feedback was provided by a neutral third party. Length: Recorded presentations- 20-30 minutes each. Role-playing sessions: ~20 minutes. PSBPS intervention- Median of 20 minutes. Frequency: Once daily Duration: Median of 4 days for PSBPS intervention |

Outcome variables: Doula training effectiveness Measurement tools: Doula PSBPS evaluation grading rubric divided into ‘poor’, ‘good’, and ‘excellent’, qualitative questionnaires (open-ended questions) for stakeholder feedback |

Kirkpatrick model |

Doula Training Pre-training performance: Doula performance was mostly in the ‘good’ range following first standardized evaluation. Post-training performance: Doula performance was mostly ‘excellent’ after training sessions. Patient feedback: “93% (n=40) recalled a doula explaining what was happening to them, and 86% (n=37) found this comforting. 67% (n=29) remembered their hand being held; of those, 28 reported it as comforting. When asked what made them feel better while in the ICU, 79% (n=34) recalled specific aspects with themes and representative responses.” Family feedback: Comments from families included those about how the intervention was soothing, helpful, reassuring, and comforting. Nurse feedback: Thirty-two bedside nurses commented. Thirty-four percent found that positivity may not reflect reality, it may overstep nurses’ roles, intervention should be longer, and better coordination may be needed. Eighty-one percent found ICU doulas to be helpful. Major themes included the intervention being soothing/relaxing to the patient. |

Two doulas were successfully trained and were able to effectively provide PSBPS, as evidenced by the doulas’ graded progress and stakeholder feedback themes. The training was beneficial to the doulas themselves, and was also reported to be helpful by patients and families. |

| Szilagyi et al., 2014 [38] | RCT | “To investigate the effect of positive suggestions to ventilated patients in ICU via pre-recorded standard text delivered via the earphones and a simple MP3 player.” | Target population: Ventilated ICU patients # of participants: 26; Control: 6, Music: 6, Suggestion: 6, Rejector: 8 Mean age: 65.34 (16.69) years Gender: 26.92% (% Female Race: Not reported |

Type of intervention: pre-recorded structured text Intervention provided by: MP3 and headphones Specific approaches: The positive suggestion intervention involved pre-recorded messages delivered in a male voice. These messages were carefully designed to provide consistent, reassuring verbal cues that actively promote recovery and healing. Examples of the recorded suggestions include:

Length: throughout ICU stay Frequency: once daily Duration: 30 min |

Outcome variables: Length of mechanical ventilation Length of ICU stay Measurement tools: Not reported; presumably recorded from patient charts or the hospital's electronic medical records system Timing of assessment: before and after the intervention |

Independent samples t-test and analysis of variance |

Mean and SD Length of mechanical ventilation Unified Control = 232.02 (165.60) Music=135.33 (96.09) Suggestion =85.25 (34.92) Mean and SD Length of stay in ICU Unified Control=314.25(178.40) Music=187.75 (108.19) Suggestion=134.24 (73.33) Statistics: Huge effect size for Length of mechanical ventilation in positive suggestion group (d = 1.46, p < 0.06) compared to the control group Very large effect sizes for Length of ICU stay in positive suggestion group as compared to the control group (d = 1.26, p < 0.07) Post-hoc analysis results showed that the length of ICU stays (134.2 ± 73.3 vs. 314.2 ± 178.4 h) and the time spent on ventilator (85.2 ± 34.9 vs. 232.0 ± 165.6 h) were significantly shorter in the positive suggestion group compared to the unified control. |

Positive suggestions, delivered through a simple and accessible method like MP3 players, can be a valuable tool in improving patient outcomes in the ICU setting. |

| Tan et al. (2020, United States) [35] | Quasi-experimental | “To investigate the feasibility of intensivists delivering psychological support based on positive suggestions (PSBPS) to reduce intubated patients’ psychological distress.” |

Target population: Intubated patients with expected ICU stays of greater than 48 hours # of participants: 76 patients in total. Thirteen in the intervention group, and 63 in the control group. Mean age: 67 (57-72) years for the intervention group. 61 (53-70) years for the control group. Gender: 6 (46%) female in the intervention group. 29 (46%) female in the control group Race: Not reported |

Type of intervention: In-hospital, PSBPS intervention Intervention provided by: Three study intensivists Specific approaches: “(1) Physicians developed rapport with patients, (2) Once patient is off sedation and able to communicate, team gathered bidirectional connection by having patient follow simple directions and have the patient be more active in treatment, (3) A final debrief- the patient is informed of what to expect after transferring to a recovery ward, fears are explored, and ICU experience is normalized. Therapeutic touch is also utilized.” Length: Median of 7 (5-12) minutes Frequency: Once daily Duration: Every day of patient’s ICU stay. Median of 4 days (IQR 2-6) |

Outcome variables: Feasibility (primary outcome), anxiety, depression, stress Measurement tools: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A, HADS-D), Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Blind (MoCA-BLIND), Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) |

Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Pearson chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, linear regression models |

Post-test (Intervention): MoCA-BLIND score = 16 (13 to 20). HADS-D score = 5 (4 to 9). HADS-A score = 6 (3 to 9). IES-R intrusion score = 0.9 (0.1 to 1.9). IES-R avoidance score = 1.1 (0.1 to 2.3). IES-R hyperarousal score = 1.3 (0.2 to 1.7). Post-test (Control): MoCA-BLIND score = 17 (15 to 19). HADS-D score = 6 (3 to 9). HADS-A score = 7 (5 to 11). IES-R intrusion score = 1.0 (0.5 to 1.9). IES-R avoidance score = 0.8 (0.3 to 1.4). IES-R hyperarousal score = 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0). Statistics: MoCA-BLIND <18 odds ratio 1.5(P=0.95). HADS-D ≥8 odds ratio 0.74(P=0.64). HADS-A ≥8 odds ratio 0.38(P=0.24). IES-R <1.6 odds ratio 1.04 (P=0.95). |

This intervention was feasible, as evidenced by the high completion rate, minimal session interruptions, absence of adverse events, and acceptance from patients and their family members. Positive suggestion interventions coupled with medical treatment may be an effective method of reducing psychological distress in mechanically intubated patients. A larger randomized study may be needed to confirm the efficacy of PSBPS. |

| Ong et al. (2020, United States) [36] | Quasi-experimental | “To evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of using meditative virtual reality (VR) to improve the hospital experience of ICU patients.” |

Target population: ICU patients from surgical and trauma ICUs # of participants: 46 patients in the intervention group. No control group identified in this study. Mean age: 50 (± 18) years Gender: 30 (65%) male Race: 8 (18%) Black, 36 (78%) White, 2 (4%) other unspecified ethnicities |

Type of intervention: Guided virtual VR-based meditative intervention Intervention provided by: Study staff Specific approaches: A VR system that “consisted of a smartphone placed in a Google Daydream (vr.google.com/daydream) headset and a pair of Bluetooth headphones”, collectively referred to as Digital Rehabilitation Environment Augmenting Medical System (DREAMS). ‘Google Spotlight Stories’ Pearl” (atap.google.com/spotlight-stories) was used to provide an orientation to VR, and ‘RelaxVR’ was also used to “provide patients with a calm immersive scene with voice-guided meditation that promoted breath control and relaxation”. Length: 5-20 minutes Frequency: Once daily Duration: 7 days |

Outcome variables: Pain, sleep quality, affect, and delirium state Measurement tools: Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS), Richards-Campbell Sleep Questionnaire (RCSQ), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS0, Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAMS-ICU). Questionnaire also administered to collect qualitative comments. |

Paired t tests and mixed models |

Pain: Dosage and frequency of opioid medications decreased at a rate of 12.9%. (p > 0.05, 95% CI, 21.7–4.03) Sleep: RCSQ score improved by 4.56 (p > 0.05, 95% CI, 1.06–8.06). Affect: statistically significant decreases in anxiety (estimate = 2.17; p < 0.05, 95% CI, –4.23 to –0.106) and depression (estimate =-1.25, p >,0.05, -95% CI, –2.37 to –0.129) noted from before the first exposure to before the third exposure Delirium: 13 patients of total 46 were delirious at least 1 day during admission. Seven participants were delirious prior to study but recovered before enrolment and remained non-delirious. Six became delirious after DREAMS. Qualitative comments: Participants found DREAMS to be comfortable, enjoyable, and helpful for pain management. They expressed mixed feelings as to whether it helped them sleep better or not. Common themes included novelty of VR, emotionally evocative, relaxing, technical frustrations, and temporary effects. |

The use of meditative VR technology in the ICU was generally well-received by patients. The intervention improved patients’ experiences in the ICU by reducing anxiety and depression. |

| Wade et al. (2018, United Kingdom) [41] | Mixed Methods Study | To develop and test the feasibility of a psychological intervention to reduce acute stress and prevent future morbidity in critical care patients. |

Target population: ICU patients # of participants: Intervention feasibility study- 127 patients. Trial feasibility study- 86 patients. No control group identified in this study. Mean age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Race: Not reported |

Type of intervention: Psychological support Intervention provided by: Trained Provision Of Psychological support to People in Intensive care (POPPI) nurses Specific approaches: “Course materials were provided to train staff to create a therapeutic environment, to identify patients with acute stress, and to deliver three stress support sessions and a relaxation and recovery program”. Length: Median length of sessions 1 to 3 were 35, 30, and 30 minutes, respectively. Frequency: 44 patients received stress support sessions. 39 received 2 or 3 sessions and 5 received 1 session only. However, the intervention was designed to deliver 3 sessions per patient. Duration: Sessions started within 48 hours of Intensive care Psychological Assessment Tool (IPAT) screening and ideally completed the three sessions within one week. |

Outcome variables: Feasibility and acceptability, stress Measurement tools: Nurse and patient feasibility questionnaires, focus groups administered to nurses, “stress thermometers” on which patient’s reported their stress levels from 0-10 at the beginning and end of each stress support session, PTSD Symptom Severity Scale – Self-Report (PSS-SR), and the 10-Item Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) |

Patient satisfaction questionnaires |

Intervention feasibility study: All 10 POPPI nurses rated the face-to-face course as ‘good’ with nine (90%) rating relevance to their new role as ‘good’. 14 (93%) patients rated their satisfaction with stress support sessions as ‘good’. Twelve (80%) rated the number and duration of sessions as ‘just right’. Ten (67%) patients found they learned good coping strategies from the program. Stress reduced by a median of 3 points (IQR 1-5 points) from the start of the first session to the end of the third session among the 25 patients who received all three sessions. Trial feasibility study: “Completeness of the primary outcome measure (PSS-SR) was very good. From 1054 fields, only 24 (2.3%) had missing data.” Qualitative comments: Nurses found that the stress support sessions were welcomed and rewarding by patients and staff. They reported that the training had raised awareness, changed staff thinking, and led to better unit environments. Patient feedback on the stress support sessions included “every hospital should have it”, “it seemed a life saver”, and “I hope POPPI will eventually be used in all ICUs”. |

The POPPI psychological intervention to reduce stress and prevent long-term morbidity for critical care patients was feasible, acceptable and ready for evaluation in a cRCT. |

| Yang et al. (2020, China) [40] | Quasi-experimental | “To explore the relationship between psychosocial support related factors and the mental health of COVID-19 positive patients.” |

Target population: COVID-19 positive patients admitted to an isolated ICU # of participants: 35 patients in the intervention group. No control group identified in this study. Mean age: 57.00 (± 13.44) years Gender: 21 (60%) male, 14 (40%) female Race: Not reported |

Type of intervention: Psychological, face-to-face intervention focusing on relaxation and positive support Intervention provided by: A trained psychotherapist and nurse Specific approaches: In-person interview to “evaluate the psychosocial impact of such an infectious disease on patients and their family members and close friends”, as well as a face-to-face intervention and online consulting. The face-to-face intervention included “listening, positive attention, supportive psychotherapy, empathy, muscle and breath relaxation, and cognitive behavioural therapy. Length: 15-30 minutes Frequency: 3x/week Duration: Not available |

Outcome variables: Sleep, depression, anxiety, and social support Measurement tools: Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7), Social Support Rate Scale (SSRS) |

ANOVA test, chi-square test, and linear regression models |

Pre-test vs. post-test: Mean PSQI: 11.20 (± 5.06) vs. 49.16 (± 31.27), p<0.0001 Mean PHQ-9 = 8.80 (± 4.26) vs 52.15 (± 42.35), p<0.0001 Mean GAD-7 score = 10.69 (± 5.62) vs 63.86 (± 42.62), p<0.0001). Mean SSRS score = 25.57 (± 4.60) vs 29.94 (± 3.15), P=0.046 Statistics: Improved sleep quality noted after intervention and was positively associated with improvement from COVID-19 (P=0.000) and better social support (P=0.046). |

“Physical and psychological well-being and sleep are affected by many social support related factors”. Administering psychological interventions to COVID-19 patients in countries outside of China may also prove beneficial. |

| Author and Date | Bannon et al. (2020)[32] | Berning et al. (2016)[33] | Elham et al. (2015)[37] | Heilmann et al. (2016)[39] | Karnatovskaia et al. (2021)[34] | Ong et al. (2020)[36] | Szilagyi et al. (2014) [38] | Tan et al. (2020) [35] | Wade et al. (2018)[41] | Yang et al. (2020)[40] |

| Is the source population or source area well described? | + | + | + | ++ | - | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Is the eligible population or area representative of the source population or area? | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Do the selected participants or areas represent the eligible population or area? | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Was selection bias minimised? | ++ | NR | NR | ++ | NR | NR | ++ | - | + | NR |

| Were interventions (and comparisons) well described and appropriate? | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Was the allocation concealed? | ++ | NR | NR | ++ | NA | NA | ++ | - | NR | NR |

| Were participants or investigators blind to exposure and comparison? | - | NA | NR | + | NA | NA | ++ | - | NR | NA |

| Was the exposure to the intervention and comparison adequate? | + | NA | ++ | + | NA | NA | ++ | + | + | NA |

| Was contamination acceptably low? | ++ | NA | ++ | ++ | NA | NA | ++ | ++ | NR | NA |

| Were other interventions similar in both groups? | ++ | NA | ++ | ++ | NA | NA | ++ | ++ | NA | NA |

| Were all participants accounted for at study conclusion? | - | ++ | - | - | ++ | NR | ++ | ++ | ++ | NR |

| Did the setting reflect standard Canadian practice? | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Did the intervention or control comparison reflect standard Canadian practice? | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Were outcome measures reliable? | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + |

| Were all outcome measurements complete? | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | - | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| Were all important outcomes assessed? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Were outcomes relevant? | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Were there similar follow-up times in exposure and comparison groups? | ++ | NA | ++ | ++ | NA | NA | NA | ++ | NA | NA |

| Was follow-up time meaningful? | + | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ | NA | ++ | NR | + |

| Were exposure and comparison groups similar at baseline? If not, were these adjusted? | ++ | NA | ++ | ++ | NA | NA | ++ | ++ | ++ | NA |

| Was intention to treat (ITT) analysis conducted? | NR | NR | NR | NR | NA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Was the study sufficiently powered to detect an intervention effect (if one exists)? | NR | NR | - | ++ | NR | NR | - | - | NR | NR |

| Were the estimates of effect size given or calculable? | NR | NR | NR | + | NR | NR | ++ | NR | NR | NR |

| Were the analytical methods appropriate? | ++ | + | + | ++ | + | + | ++ | + | - | + |

| Was the precision of intervention effects given or calculable? Were they meaningful? | ++ | + | + | ++ | NA | + | ++ | ++ | - | + |

| Are the study results internally valid (i.e., unbiased)? | + | + | - | ++ | + | + | ++ | + | + | + |

| Are the findings generalizable to the source population (i.e., externally valid)? | + | ++ | + | ++ | - | + | ++ | + | + | + |

| Author, year | Intervention | Psychological outcome | Effect size |

| |||

| Bannon et al., 2021[32] | Recovering Together | Anxiety PTS |

d=-1.25 d=-0.83 |

| Ong et al. (2020) [36] | virtual reality-based meditative intervention | Anxiety Depression |

inadequate data to calculate effect size |

| |||

| Yang et al. (2020) [40] | in-person relaxation and support | Depression Anxiety Social support |

inadequate data to calculate effect size |

| Wade et al. (2018) [41] | Psychological support | Stress Coping |

inadequate data to calculate effect size |

| Heilmann et al. (2016) [39] | psychotherapy to provide emotional support |

Immediately After intervention: cognitive anxiety affective anxiety VAS On postoperative day 5: VAS affective anxiety Cognitive anxiety |

d=-0.39 d=-0.125 d=-0.20 d=-0.28 d=-0.125 d=-0.17 |

| |||

| Elham et al. (2015) [37] | spiritual and religious based interventions | SWB S-anxiety T-anxiety |

inadequate data to calculate effect size |

| Berning et al. (2016) [33] | spiritual based interventions | Anxiety Stress |

inadequate data to calculate effect size |

| |||

| Tan et al., (2020) [35] | psychological suport based on positive suggestions | Anxiety Depression Stress |

inadequate data to calculate effect size |

| Karnatovskaia et al., 2021 [34] | Psychological Support Based on Positive Suggestions | Stress Coping |

inadequate data to calculate effect size |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).