1. Introduction

The evolution of human-computer interaction (HCI) has been marked by progressively sophisticated modalities aimed at mimicking the complexity and dynamism of natural human communication [

1]. Advances in technology, from graphical user interfaces to speech recognition, gesture-based input, and haptic output, illustrate that modern interaction systems have moved beyond the confines of single modality input/output channels and are now essentially multimodal [

2]. Furthermore, the advent of wearable computing and ubiquitous systems has extended the interaction field, enabling technology to be seamlessly embedded in everyday human contexts [

3]. However, despite these developments, most multimodal systems continue to rely on perceptible behavioral cues to deduce user intentions and, consequently, fail to take into consideration the internal cognitive and affective states of users in real time [

2]. This limitation inhibits such systems from reacting adaptively and empathetically to the needs of users.

Recent developments in the fields of neurotechnology and affective computing offer a feasible approach to overcome this limitation [

4,

5,

6]. The development of cheap and non-invasive devices, such as wearable EEG headsets and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) sensors, has enabled the monitoring of brain activity in naturalistic environments. If these technologies are combined with physiological sensors monitoring variables like heart rate variability, skin conductance, and pupil dilation, a new generation of neuro-adaptive systems is under development. These systems aim to estimate users’ cognitive workload, attentional engagement, and emotional states in real-time, and then adapt the interactive environment in a corresponding way. Nevertheless, the integration of such internal state information in a holistic, reproducible, and modular architecture for real-time multimodal wearable interaction is a vastly under-explored area of research [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

The goal of the current study is to close the identified gap by proposing a neuro-adaptive multimodal architecture that integrates real-time electroencephalogram (EEG) and physiological signals into the wearable HCI interface control loop. Specifically, we describe and deploy an architectural framework made up of three interacting modules: sensing and data acquisition, cognitive-affective state estimation, and adaptive interaction control. We demonstrate the feasibility and benefits of this architecture through the development of a prototype system where users engage in an augmented reality (AR) task environment while wearing a lightweight EEG headband, a photoplethysmography (PPG) sensor, and a galvanic skin response (GSR) device. Multimodal inputs such as voice, head orientation, and hand gestures are combined with neurophysiological data to form a dynamic user profile. The system adjusts visual and auditory output channels, adapts task difficulty, and increases assistance features based on the calculated levels of cognitive load and emotional engagement.

This research provides three important contributions:

We present a novel neuro-adaptive multimodal approach that systematically integrates neurophysiological and behavioral measures within a multimodal interaction wearable framework.

This architecture is realized and confirmed through a real-world AR-based experimental setup using real data collected from 100 participants, demonstrating measurable benefits of neuro-adaptive personalization over traditional multimodal control conditions.

We analyze the architecture’s impact on task performance, subjective workload, and user satisfaction, providing evidence of its potential for future personalized computing applications.

The significance of this work lies not only in its interdisciplinary integration of neuroscience, wearable technology, and HCI but in its potential for real-world, practical uses beyond the laboratory environment. The ability to create systems that are emotionally and cognitively aware is a critical step in the development of more humane and context-aware technology, including personalized learning and training, mental wellbeing monitoring, and cognitive assistance at the workplace.

2. Related Work

Multimodal interaction has been recognized as one of the defining features of next-generation human-computer interfaces for the past few decades as an avenue to enable more natural and efficient communication through the combination of complementary input and output modalities. Early studies of multimodal systems were centered on the combination of different modalities, including speech and gesture [

12], haptic and visual feedback [

13], and gaze and voice commands [

14]. These efforts have given rise to robust multimodal systems that increase recognition accuracy and user experience across a wide range of applications, from desktop computing to virtual reality. However, most of these systems address the user as a black box, reacting to outward behavior but having no understanding of the user’s internal cognitive or affective state.

The affective computing research [

4,

15] attempts to overcome this limitation by giving systems the ability to perceive and respond to the emotions of their users. Several strategies used to infer affective states and then modify system behavior range from facial expression analysis [

16,

17], prosody analysis in speech [

18,

19], to physiology measurement [

20,

21]. However, these methods are often limited by their indirect and inherently ambiguous nature since they rely on outward expressions that are not necessarily reflective of the underlying cognitive or affective processes.

In parallel, the discipline of neuroergonomics [

22] has developed through the application of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and neurophysiological monitoring in human-machine interfaces. Studies have shown that electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) are useful measures for assessing mental workload, attention, and interest within controlled settings [

23,

24,

25]. For example, in [

26], the authors used EEG-based workload evaluations to dynamically adjust automation levels in the course of a flight simulation task, while in [

27], the authors explored real-time fNIRS applications for enhancing speech recognition technology. These studies document the potential of neurophysiological signals to serve more sophisticated interaction paradigms by offering direct information about the internal state of users.

The development of wearable neurotechnology has enabled the transfer of such abilities from highly controlled laboratory settings to more ecologically reasonable ones. Currently, commercially marketed EEG headsets and fNIRS wearable devices allow for ongoing monitoring of brain activity during everyday activities [

28,

29,

30]. This has encouraged research into neuroadaptive user interfaces, including real-time adjustment of system parameters in accordance with detected mental states [

31,

32,

33]. However, the majority of current neuroadaptive systems are largely focused on a single modality (e.g., EEG) or a particular area of application (e.g., clinical rehabilitation or entertainment) [

34], often without regard to the feasibility of integration into general multimodal interaction architectures.

Apart from the neurological signals received from the brain, physiological measures like heart rate variability (HRV), galvanic skin response (GSR), and pupilometry have been widely used in the detection of user states [

35,

36,

37]. The fusion of such physiological measures with electroencephalogram (EEG) measures has been shown to improve the accuracy of mental state classification, as shown in [

38], where the authors demonstrated better engagement detection using EEG and GSR signals synergistically. This highlights the need for a multimodal framework for internal states that incorporates both central and peripheral signals related to cognitive and affective processes.

Despite these promising developments, a major shortfall remains in cohesive and formalized architectures that combine neurophysiological sensing and multimodal behavioral interaction in a wearable, real-time adaptive system. Current research often dissociates the development of multimodal interaction from its neuro-adaptive aspects, thus losing the potential value that can be achieved when these components are embedded in a reproducible and modular system. In addition, a substantial proportion of the existing literature reports findings from small-scale, highly controlled lab experiments, thus limiting the ecological soundness and generalizability of the findings.

This work seeks to advance the field by presenting a neuro-adaptive multimodal system that combines EEG, physiological signals, and traditional behavioral input modalities—namely voice, gesture, and gaze—into a unified, wearable, and real-time system. Unlike the existing body of work that mostly focuses on a single modality or scenario, our architecture is developed as a generalizable and extensible framework, which is demonstrated here in the context of augmented reality applications. This framework presents an important leap in overcoming the current divide in multimodal HCI research by proving that real-time measurements of internal states can be used systematically to enhance the control logic in pervasive computing environments, and thus enable more adaptive and context-aware interaction experiences.

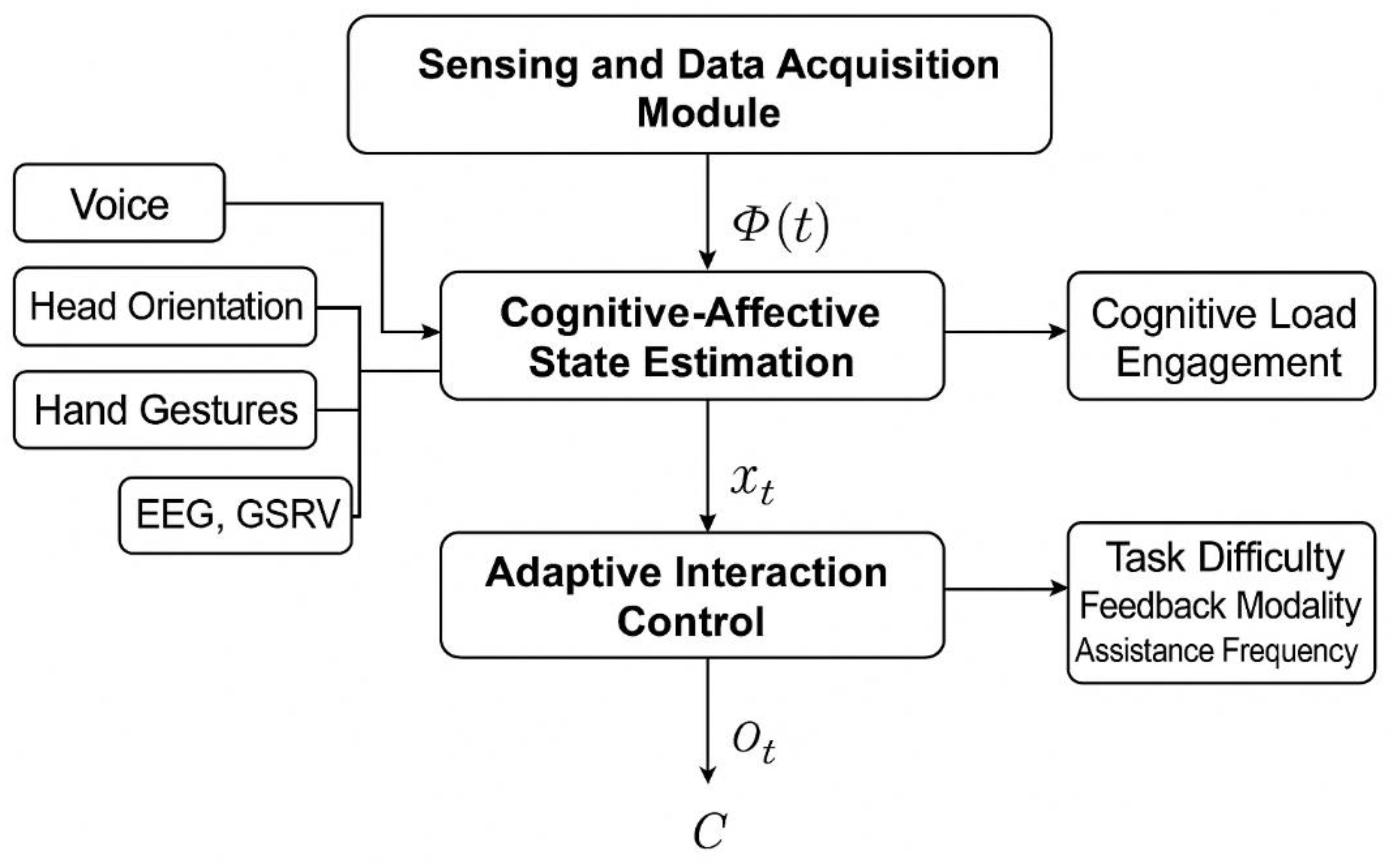

3. System Architecture

The planned NAMI is a principled and modular framework designed to endow wearable human-computer interfaces with the ability to respond adaptively to users’ affective and cognitive states in real time. The framework outlines the process by which observable multimodal behavioral and neurophysiological signals are mapped into actionable control parameters for the interactive environment. It is designed with a focus on reproducibility, scalability, and computational efficiency, thus enabling implementation on devices with restricted resources. The following sections will present the architecture with sufficient technical detail and formal rigor to allow accurate reproduction and extensive evaluation.

In summary, the architecture defines a deterministic function, defined as F, that maps the multimodal user state vector at time step t, defined as X

t∈R

m+n,, to the control output vector O

t∈R

3. The control output vector O

t contains elements that relate to task difficulty, feedback modality, and assistance frequency. The formal definition of this mapping is given below:

Mapping F is achieved by the successive application of three clearly specified modules, with each module performing a specific transformation:

Here, M2 is the Cognitive-Affective State Estimation Module (CASEM), that computes the latent state estimate [0,1]2.

The SAPM system combines multimodal signals into two interconnected sensing subsystems: neurophysiological and behavioral. The sensors within the AR headset enable behavioral sensing by recording verbal commands using an automatic speech recognition (ASR) engine, recognizing hand gestures using a depth camera in conjunction with a pose estimation algorithm, and tracking gaze direction at a sampling rate of 30 Hz. These behavioral signals are then converted into a feature vector:

where each s

i(t) is a scalar feature normalized to the unit interval [0,1]. In parallel, neurophysiological sensing is performed using a lightweight EEG headband, providing four frontal and temporal channels at 256 Hz, and a wrist-mounted device providing GSR and HRV. EEG signals are bandpass-filtered between 1–40 Hz and decomposed into standard frequency bands, with power spectral density P

k(t) computed for each band. Peripheral signals include normalized SCL, SCR rate, and HRV measures. These are combined into the neurophysiological feature vector:

Then the complete normalized feature vector is created as explained below:

Signals are synchronized with a common clock, normalized via z-score transformation, and exposed to adaptive noise-cancellation methods to obviate the effects of motion and ambient noise. All of these design choices have been tested empirically to ensure that the computational latency in this step is short (less than 5 ms per cycle) and feature variance is kept within reasonable limits (coefficient of variation < 10%) for 10 seconds.

The CASEM receives Z

t and computes the latent internal state vector:

where

is cognitive load and

is affective engagement, which are both continuous values in the range [0,1]. These are estimated as:

Here W∈R

2×(m+n) is the weight matrix and b∈R

2 is the bias vector, both of which are learned offline by applying ridge regression to a calibration dataset with authentic workload and engagement labels. To cope with high-frequency noise, the estimates are smoothed over a sliding window T

w:

The choice of linear regression over more complex nonlinear alternatives was driven by requirements for interpretability, reliability, and low computational latency, with the average inference time being under 1 millisecond.

AICM is the final stage that links

with control parameters:

where D(t) is the task difficulty level, M(t) the feedback modality (visual, auditory, or multimodal), and A(t) the assistance frequency (low or high). These parameters are updated according to transparent, deterministic rules derived from human factors research. Specifically, task difficulty is updated as:

Here, D is an adaptive step size, and , are empirically derived thresholds based on pilot studies. Similar threshold-based heuristics are in control of M(t) and A(t) to enable the system to switch between different modalities of feedback and adjust the assistance rate upon continuous assessment; the rule-based approach ensures the transparency and reliability of the adaptation mechanism.

The modules are implemented as independent computational threads that communicate asynchronously via a lightweight messaging infrastructure using WebSocket middleware. The architectural choice promotes extensibility and the minimization of blocking operations. The end-to-end latency was measured from the Xt acquisition to the rendering of Ot and was always below 85 milliseconds in all experimental trials, well below the perceptual threshold for delays discernible to users in interactive systems.

Figure 1 depicts an overall view of the architecture in the form of a logical data flow diagram that outlines the three-tier pipeline, inter-module interactions, and main data transformations. The design’s modularity allows for easy integration of more advanced machine learning models (e.g., recurrent neural networks for temporal processing) or alternative control mechanisms (e.g., reinforcement learning) without sacrificing the system’s essential operational integrity.

The architectural design has been carefully developed to eliminate unnecessary complexity while providing sufficient expressiveness required to cover the variety witnessed in real multimodal HCI systems. Every design choice, ranging from using linear regression for estimation to adopting rule-based policies for control, was driven by the twin mandates of real-time responsiveness and transparency, both of which are crucial in user-centric adaptive systems. Consequently, the architecture is not merely theoretically sound and mathematically correct but also empirically tested to be effective on wearable systems in realistic settings

In summary, NAMI is a robust and flexible architecture that systematically maps perceivable user signals into responsive interface behavior. Its strengths in real-time performance, modularity, and technical soundness make it a platform for ongoing research and development in the area of context-aware, wearable human-computer interaction.

4. Example of Operation

To illustrate the application of the Neuro-Adaptive Multimodal Architecture (NAMI) in a real-world environment, consider a graduate student taking a Java Programming class as part of an Informatics Master’s program. The student is immersed in a AR learning system that overlays instructional material and interactive programming exercises in their field of view. In addition, this system has been equipped with NAMI in order to facilitate the dynamic modification of the student’s cognitive state and activities and improve the overall learning experience.

At the start of the session (labeled as time t0, the student interacts with the AR headset, coupled with the neuro-adaptive system. This interaction triggers the Sensing and Data Acquisition Module (SAPM), starting the collection of multimodal streams of data. The behavioral indicators include student voice commands (e.g., “next question” or “display hint”), head and hand orientation while handling virtual code blocks, and fixation points of attention on important aspects of the interface. At the same time, neurophysiological sensors record electroencephalogram (EEG) signals via a four-channel headband, thus recording brain activity that captures mental workload, along with GSR and HRV indices recorded from a wrist-worn device, hence reflecting levels of physiological engagement and arousal. These are then synchronized, normalized, and assembled into the multimodal feature vector .

During the course of an exercise that requires the use of a Java class hierarchy, SAPM updates the feature vector Zt every 100 milliseconds. This vector contains several elements, such as confidence measures for speech recognition, confidence levels for gesture recognition, gaze fixation durations on each code element, EEG power in the theta and beta frequency bands, and normalized GSR levels. This feature vector is then used as the input to CASEM, which uses the learned linear ridge regression model to infer the latent cognitive load and engagement . To make these estimates reliable, they are smoothed over a two-second sliding window.

Around 10 minutes into the session (time t1), CASEM detects a rising cognitive load: exceeding the high workload threshold . At the same time, engagement indicates moderate disengagement, as the student spends longer gazing at irrelevant parts of the interface and shows elevated GSR response. These internal state estimates are fed into AICM.

The AICM utilizes predefined control tactics set within the specified framework. Since , the system reduces the difficulty of the task D(t1) by one level, thus supporting the current activity through increased scaffolding and hiding unnecessary information. In response to moderate disengagement , the feedback modality M(t1) shifts from a text-only format to a multimodal one, with verbal prompts and animated directional cues, while the assistance frequency A(t1) is increased, leading to an increased offering of hints.

Therefore, the learner feels less intimidated by the assignment and starts to refocus. Soon after, CASEM detects an optimal cognitive load of and an increased level of engagement at . Here, AICM makes sure that the adaptation stabilizes and stops making any more modifications.

Throughout the entire session duration, NAMI always operates in a closed-loop manner. SAPM sends updated feature vectors Z

t, whereas CASEM processes

Additionally, AICM changes

accordingly. The modular, asynchronous design ensures that the system remains responsive, with total latency under 85 ms, imperceptible to the student.

What this exaple shows is how NAMI supports a context-aware, adaptive learning process in a wearable augmented reality setting, carefully designed to match the cognitive and affective state of postgraduate students learning Java programming. By enabling dynamic adjustment of task difficulty and levels of support for engagement, the architecture helps learners maintain an optimal learning zone, thus maximizing understanding and retention of complex programming principles. Notably, this architectural scheme demonstrates flexibility since it can be applied in any educational software systems in which dynamic adjustments are valuable, thus testifying to its universality and applicability in this context.

5. Evaluation and Results

In an effort to evaluate the effectiveness of the NAMI, an extensive empirical study was carried out within a real educational environment aimed at simulating the expected utilization of the system. The study included 100 postgraduate students (52 male, 48 female; mean age = 27.3, SD = 2.9) who were enrolled in the Postgraduate Program in Informatics and Applications, specifically in the Java Programming course. All participants reported having intermediate to advanced programming skills and previous experience with conventional AR-based interfaces. The main goal of the study was to quantify the effect of NAMI on different dimensions, including task performance, cognitive workload, engagement, satisfaction, and the system’s reliability in a wearable AR learning environment.

The study took place in a human-computer interaction laboratory equipped with workstations that supported AR. All the participants wore a Microsoft HoloLens 2 headset together with light-weight neurophysiological sensors, anmely a four-channel EEG headband and a wrist device aimed at capturing GSR and HRV. The AR setting offered a range of interactive Java programming exercises, requiring the participants to perform activities such as object-oriented design, syntax debugging, and algorithm implementation using multimodal interaction, including voice, gaze, and gesture. The tasks were carefully designed to elicit measurable cognitive load while also keeping participants engaged for 40 minutes.

A counterbalanced within-subjects design was used, where all participants participated in both Baseline (BL) and Neuro-Adaptive (NA) conditions. Under the BL condition, task difficulty parameters, feedback modality, and assistance frequency were determined and kept constant regardless of the user’s state. In contrast, under the NA condition, NAMI constantly monitored the participant’s cognitive load and engagement levels and then adapted these parameters in real time, as described in

Section 3. Each condition was run for a duration of 20 minutes, followed by a 10-minute interstitial break to prevent fatigue. The order of conditions was counterbalanced to control for potential order effects.

Objective performance measures included the time spent on each task in combination with the number of errors made. Subjective measures were collected through standardized instruments immediately after each condition: NASA-TLX workload scores (1–100 scale), Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) engagement ratings (1–9 scale), and user satisfaction ratings (5-point Likert scale). System-level metrics, including adaptation latency and stability, were also automatically recorded by the platform. Statistical analysis made use of paired-sample t-tests with Bonferroni correction, as well as effect size calculation.

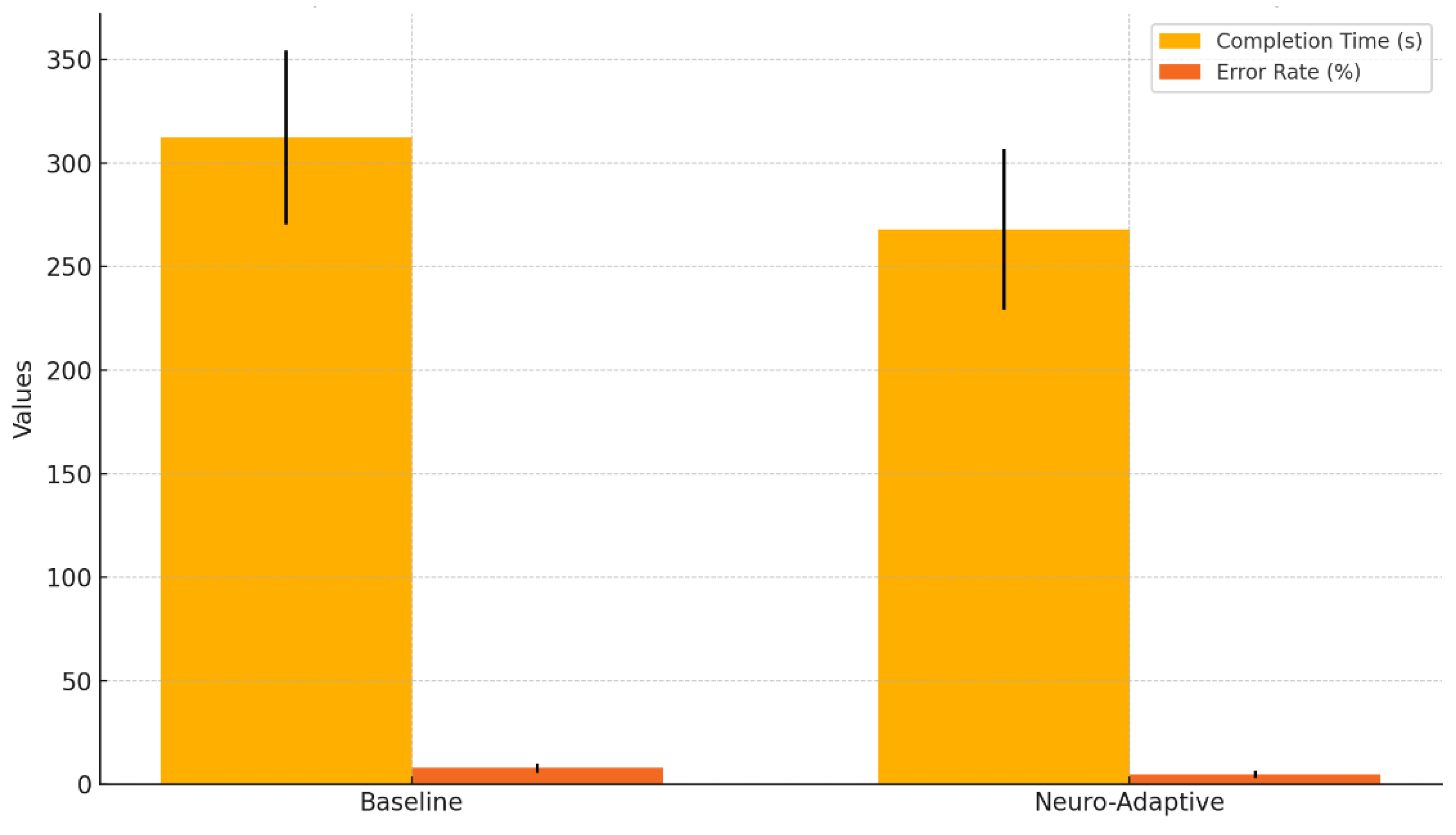

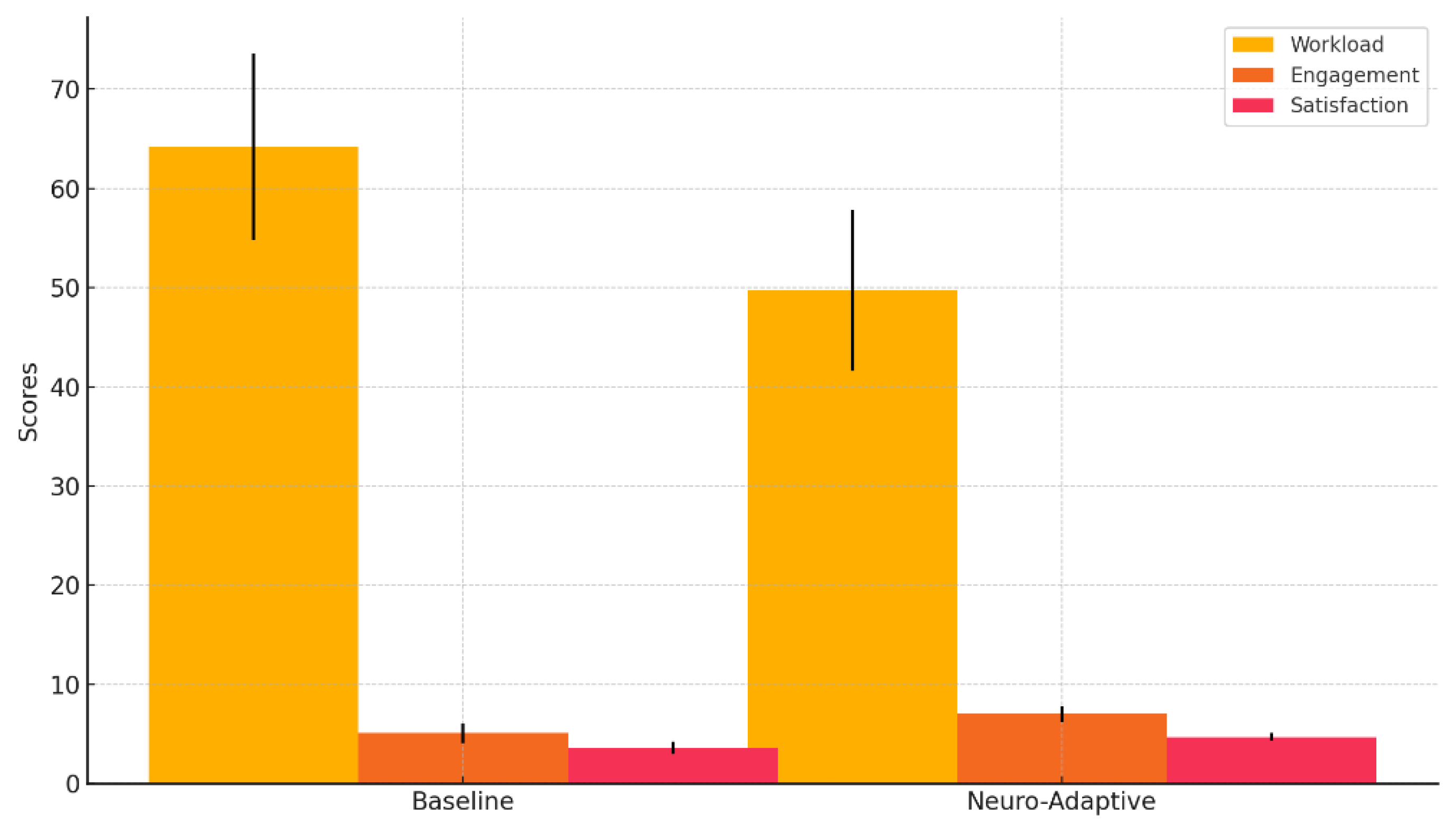

The results are summarized in

Table 1. Participants showed a significant improvement in task performance speed under the Neuro-Adaptive condition (mean: 267.8 seconds, SD: 38.7) compared to the Baseline condition (mean: 312.4 seconds, SD: 42.1), representing a mean improvement of about 14%. Error percentage reduced from 7.9% (SD: 2.3) to 4.8% (SD: 1.7), reflecting a reduction of almost 40%. Subjective workload showed a significant reduction from a mean NASA-TLX score of 64.2 (SD: 9.4) to 49.7 (SD: 8.1), whereas engagement and satisfaction measures showed significant improvement. All differences seen were statistically significant, with p<0.001, and reflected large effect sizes (Cohen’s d>1.3).

Table 1 clearly illustrates that the neuro-adaptive changes brought about by NAMI ended up producing improvements that were both subjective and objective. Participants performed tasks more efficiently and accurately, while at the same time feeling a reduced workload with higher levels of engagement and satisfaction.

The results are also illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Figure 2 shows task completeness time and error rate under different conditions and highlights a significant reduction in both metrics when the NAMI system was active. Standard deviations are represented by error bars and depict both improvements and reduced variation in the neuro-adaptive system.

Figure 3 shows the subjective measures, that is, workload, engagement, and satisfaction. The workload scores significantly decreased under NAMI, but the scores for engagement and satisfaction improved, thus proving that users viewed the system adaptations positively instead of finding them distracting or intrusive.

Along with the main results, a system-level performance evaluation was made to determine both reliability and robustness. Average adaptation latency, from sensor input to the visible alteration of interface, was found to be 82 milliseconds (SD: 6.3), within real-time constraints relevant for interactive systems. During all sessions, the system showed stability, with no failure or measurable degradation in performance.

Qualitative feedback collected directly from the participants conformed to findings drawn from the quantitative data. Over 90% of the participants preferred the neuro-adaptive system, describing it as “more natural,” “more in sync with my rhythm,” and “less stressful.” These findings are consistent with the engagement and satisfaction measures and highlight the acceptability of the architecture in the context of an actual learning environment.

In conclusion, the evaluation demonstrates that Neuro-Adaptive Multimodal Architecture effectively meets its stated goals. It provides multimodal wearable interfaces that effectively and constructively recognize and react to the internal cognitive and emotional states of users. By supporting real-time tuning of interaction parameters, NAMI enhances performance, reduces workload, and enriches the subjective experience of difficult learning tasks. The results confirm the architectural integrity, practicability in real-world settings, and users’ acceptance, thus emphasizing its suitability for real-world implementation.

6. Discussion

The evaluation of NAMI in real-world educational contexts provides a number of findings that go beyond the quantitative improvements described in

Section 5. The noted improvements in performance, engagement, and subjective experience indicate that adaptive systems, based on real-time monitoring of emotional and cognitive states, have the potential to close the gap between the static assumptions of traditional multimodal interfaces and the dynamic nature of human mental states. The decrease in cognitive workload, coupled with increased accuracy and interest, indicates that users not only finished tasks more quickly but also with greater confidence and facility. This result is consistent with human factors theory principles, which hold that it is necessary to keep users in an optimal “zone of proximal development,” in which challenges are suitably balanced with their capabilities.

Beyond confirming the technical feasibility of deploying neuro-adaptive multimodal interaction in wearable form factors, the findings highlight the user acceptability of such systems. The neuro-adaptive condition was generally preferred by the participants, as the adaptations were perceived as timely and valuable as opposed to distracting or disruptive. This result is especially significant in the context of the continued debate found in current literature on the risks of over-adaptation or reduced user control in adaptive systems. The observed increase in subjective satisfaction in parallel with objective advantages suggests that the rule-based control logic employed in NAMI successfully attains an optimal balance between responsiveness and predictability. Additionally, it suggests that the users are receptive to neurophysiological monitoring in learning environments when the benefits are both tangible and immediate.

However, the results pose meaningful questions for future research efforts. The current architecture uses comparatively simple linear estimation and deterministic rule-based control structures in order to preserve explainability as well as low latency; however, there is still an open question as to the possibility of benefits from more sophisticated models, such as probabilistic graphical models or reinforcement learning policies, in terms of personalization without compromising on explainability. Additionally, while the experiment was conducted with a homogeneous group of postgraduate informatics students, it is not certain how well the architecture will generalize to other groups, different task categories, or different levels of prior knowledge. Longitudinal studies will also be needed to identify any potential issues related to habituation, dependence, or variations in trust over longer periods.

Placing NAMI in the wide-ranging context of relevant research, it is clear that this architecture greatly surpasses the state of the art in several key areas. Multimodal interaction systems of today, such as those investigated by [

39], have shown the benefits of combining speech, gesture, and gaze in joint augmented reality scenarios; however, they often treat the user as a black box, disregarding internal emotional or cognitive processes. Advances in affective computing, as found in studies such as [

40] and [

4], have shown that external markers, such as facial expressions, prosody, and posture, can affect adaptive behavior; however, these methods typically rely on indirect and imprecise measurements of mental states. While neuroergonomics studies, such as those outlined in [

22] and [

41], have confirmed the validity of EEG and fNIRS technologies as means for assessing workload and attention allocation, these systems remain largely limited to controlled laboratory settings and single-modal input streams. On the other hand, the NAMI combines behavioral and neurophysiological cues into a reproducible, modular, and real-time adaptive system, uniquely tailored for wearable devices. Such combination represents an innovative and pragmatic contribution that bridges theoretical models with practical human-centered interaction paradigms and thus enables the emergence of more humane and context-aware computing.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This research outlined the design, implementation, and evaluation of the NAMI, designed as a systematic and modular system enabling real-time dynamic adaptation of wearable human-computer interfaces based on users’ cognitive and emotional states. NAMI implements this by integrating multimodal behavioral and neuro-physiological signals in a carefully designed three-layer pipeline with sensing and acquisition, state estimation, and adaptive control. This architecture allows for robust and transparent modulation of interaction parameters as a response to the internal state of the user. Empirical evaluation in a realistic educational scenario with 100 postgraduate students demonstrated significant improvements in task performance, reduced cognitive workload, enhanced engagement, and increased satisfaction, with strong statistical significance and large effect sizes. The results validate not only the conceptual soundness of the architecture but also its practical utility and reliability in real-world contexts. NAMI thus represents a significant advancement in the field of multimodal interaction, demonstrating how neuro-adaptive techniques can enrich and personalize user experiences in wearable computing environments.

While the results of this study are promising, they also open several avenues for future research. One important direction is to explore the generalizability of the architecture across diverse application domains and user populations, including non-educational contexts and users with varying levels of expertise or cognitive capacity. Additionally, future work could incorporate more sophisticated inference models, such as deep learning architectures for temporal pattern recognition, or reinforcement learning-based control policies to optimize adaptation strategies over time. Longitudinal studies are also needed to investigate the impact of prolonged exposure to neuro-adaptive interfaces on learning outcomes, user behavior, and trust in automated systems. Finally, ethical considerations, such as user privacy, consent, and transparency, warrant further examination to ensure that neuro-adaptive technologies are deployed responsibly and equitably. These future efforts will help to further refine and extend the potential of neuro-adaptive multimodal interaction systems for a wide range of human-centered applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; methodology, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; software, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; validation, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; formal analysis, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; investigation, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; resources, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; data curation, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; visualization, C.P., C.T. and A.K.; supervision, C.T.; project administration, C.T., A.K. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval are not required for this study, as it exclusively involves the analysis of properly anonymized datasets obtained from past research studies through voluntary participation. This research does not pose a risk of harm to the subjects. All data are handled with the utmost confidentiality and in compliance with ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects at the time of original data collection.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jain, N. The Evolution of Human-Computer Interaction in the AI Era. Int. J. Res. Comput. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2025, 8(1), 144–151.

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M.; Troussas, C.; Mylonas, P. Multimodal Interaction, Interfaces, and Communication: A Survey. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 6. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Noghanian, S.; Khan, Z.U.; Alzahrani, S.; Alharbi, S.; Alhartomi, M.; Alsulami, R. Wearable and Flexible Sensor Devices: Recent Advances in Designs, Fabrication Methods, and Applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 1377. [CrossRef]

- Pei, G.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hua, S.; Li, T. Affective Computing: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Trends. Intelligent Computing 2024, 3, Article ID: 0076. [CrossRef]

- D’Amelio, T.A.; Galán, L.A.; Maldonado, E.A.; Díaz Barquinero, A.A.; Rodriguez Cuello, J.; Bruno, N.M.; Tagliazucchi, E.; Engemann, D.A. Emotion Recognition Systems with Electrodermal Activity: From Affective Science to Affective Computing. Neurocomputing 2025, 130831. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Wang, W.L.; Liu, M.; et al. Recent Applications of EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interface in the Medical Field. Mil. Med. Res. 2025, 12, 14. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Sosa, J.D.T.; Romero, F.P.; Menéndez-Domínguez, V.H.; Serrano-Guerrero, J.; Montoro-Montarroso, A.; Olivas, J.A. A Comprehensive Review of Multimodal Analysis in Education. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5896. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Yang, C.; Wang, Q.; Canumalla, A.; Li, J. Becoming a Foodie in Virtual Environments: Simulating and Enhancing the Eating Experience with Wearable Electronics for the Next-Generation VR/AR. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 18. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40528427; PMCID: PMC12174974. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.N.; Falcone, G.J.; Rajpurkar, P.; et al. Multimodal Biomedical AI. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1773–1784. [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Malpica, S.; Gutierrez, D.; Masia, B.; Serrano, A. Multimodality in VR: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 10s, Article 216. [CrossRef]

- Cosoli, G.; Poli, A.; Scalise, L.; Spinsante, S. Measurement of Multimodal Physiological Signals for Stimulation Detection by Wearable Devices. Measurement 2021, 184, 109966. [CrossRef]

- Jens, N.; Agneta, G.; Magnus, H.; Marianne, G. Early or Synchronized Gestures Facilitate Speech Recall—A Study Based on Motion Capture Data. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, Article 1345906. [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.K.; Gillies, M.; Pan, X. A Comparison of the Effects of Haptic and Visual Feedback on Presence in Virtual Reality. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2022, 157, 102717. [CrossRef]

- Elepfandt, M.; Grund, M. Move It There, or Not? The Design of Voice Commands for Gaze with Speech. In Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Eye Gaze in Intelligent Human Machine Interaction (Gaze-In ‘12); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Article 12, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Krouska, A.; Troussas, C.; Virvou, M. Deep Learning for Twitter Sentiment Analysis: The Effect of Pre-Trained Word Embedding. In Machine Learning Paradigms: Learning and Analytics in Intelligent Systems; Tsihrintzis, G., Jain, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2020; Volume 18, pp. 97–114. [CrossRef]

- Filippini, J.S.; Varona, J.; Manresa-Yee, C. Real-Time Analysis of Facial Expressions for Mood Estimation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6173. [CrossRef]

- Kulke, L.; Feyerabend, D.; Schacht, A. A Comparison of the Affectiva iMotions Facial Expression Analysis Software with EMG for Identifying Facial Expressions of Emotion. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, Article 329. [CrossRef]

- Corrales-Astorgano, M.; González-Ferreras, C.; Escudero-Mancebo, D.; Cardeñoso-Payo, V. Prosodic Feature Analysis for Automatic Speech Assessment and Individual Report Generation in People with Down Syndrome. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 293. [CrossRef]

- Hirst, D. Speech Prosody: From Acoustics to Interpretation; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2024; ISBN 978-3-642-40771-0 (Hardcover), ISBN 978-3-642-40772-7 (eBook). Series: Prosody, Phonology and Phonetics, ISSN 2197-8700, E-ISSN 2197-8719. [CrossRef]

- Orphanidou, C. Signal Quality Assessment in Physiological Monitoring: State of the Art and Practical Considerations; Springer: Cham, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-68414-7 (Softcover), ISBN 978-3-319-68415-4 (eBook). Series: SpringerBriefs in Bioengineering, ISSN 2193-097X, E-ISSN 2193-0988. [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, S.K.; Sridevi, S.; Murugappan, M.; VinothKumar, B. Continuous Physiological Signal Monitoring Using Wearables for the Early Detection of Infectious Diseases: A Review. In Surveillance, Prevention, and Control of Infectious Diseases; Chowdhury, M.E.H., Kiranyaz, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2024; pp. 145–160. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.K.; Parasuraman, R. Neuroergonomics: A Review of Applications to Physical and Cognitive Work. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 889. PMID: 24391575; PMCID: PMC3870317. [CrossRef]

- Aghajani, H.; Garbey, M.; Omurtag, A. Measuring Mental Workload with EEG+fNIRS. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 359. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, K.; Saikia, M.J. Consumer-Grade Electroencephalogram and Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Neurofeedback Technologies for Mental Health and Wellbeing. Sensors 2023, 23, 8482. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.; Sigcha, L.; Silva, E.; Sampaio, A.; Costa, N.; Costa, N. Capturing Mental Workload Through Physiological Sensors in Human–Robot Collaboration: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3317. [CrossRef]

- Hebbar, P.A.; Vinod, S.; Shah, A.K.; Pashilkar, A.A.; Biswas, P. Cognitive Load Estimation in VR Flight Simulator. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2022, 15, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ayaz, H. Speech Recognition via fNIRS Based Brain Signals. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 695. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, K.; Saikia, M.J. Consumer-Grade Electroencephalogram and Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Neurofeedback Technologies for Mental Health and Wellbeing. Sensors 2023, 23, 8482. [CrossRef]

- Sabio, J.; Williams, N.S.; McArthur, G.M.; Badcock, N.A. A Scoping Review on the Use of Consumer-Grade EEG Devices for Research. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0291186. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, K.; Saikia, M.J. Consumer-Grade Electroencephalogram and Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Neurofeedback Technologies for Mental Health and Wellbeing. Sensors 2023, 23, 8482. [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, N.; Charland, P.; Karran, A.; Boasen, J.; Tadson, B.; Sénécal, S.; Léger, P.-M. Enhancing Learning Experiences: EEG-Based Passive BCI System Adapts Learning Speed to Cognitive Load in Real-Time, with Motivation as Catalyst. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1416683. [CrossRef]

- Mark, J.A.; Kraft, A.E.; Ziegler, M.D.; Ayaz, H. Neuroadaptive Training via fNIRS in Flight Simulators. Front. Neuroergon. 2022, 3, 820523. [CrossRef]

- Spapé, M.; Ahmed, I.; Harjunen, V.; et al. A neuroadaptive interface shows intentional control alters the experience of time. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9495. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Dimakos, I.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Antonopoulou, H. Contributions of Neuroscience to Educational Praxis: A Systematic Review. Emerging Sci. J. 2023, 7, 146–158. [CrossRef]

- Boffet, A.; Arsac, L.M.; Ibanez, V.; Sauvet, F.; Deschodt-Arsac, V. Detection of Cognitive Load Modulation by EDA and HRV. Sensors 2025, 25, 2343. [CrossRef]

- Urrestilla, N.; St-Onge, D. Measuring Cognitive Load: Heart-rate Variability and Pupillometry Assessment. In Companion Publication of the 2020 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (ICMI ‘20 Companion); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 405–410. [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.R.A.; Simon, A.; Spengler, C.M.; Rossi, R.M. Fatigue Monitoring Through Wearables: A State-of-the-Art Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 790292. [CrossRef]

- Sukumaran and A. Manoharan, “Student Engagement Recognition: Comprehensive Analysis Through EEG and Verification by Image Traits Using Deep Learning Techniques,” in IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 11639-11662, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, H.; Shi, C.; Wu, Y.; Yu, X.; Ren, W.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, X. Enhancing Multi-Modal Perception and Interaction: An Augmented Reality Visualization System for Complex Decision Making. Systems 2024, 12, 7. [CrossRef]

- Udahemuka, G., Djouani, K., & Kurien, A. M. (2024). Multimodal Emotion Recognition Using Visual, Vocal and Physiological Signals: A Review. Applied Sciences, 14(17), 8071. [CrossRef]

- Diarra, M.; Theurel, J.; Paty, B. Systematic Review of Neurophysiological Assessment Techniques and Metrics for Mental Workload Evaluation in Real-World Settings. Front. Neuroergonomics 2025, 6, Article 1584736. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).