1. Introduction

Patients with psoriasis have an approximately 30% risk of developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which is associated with severe musculoskeletal damage, high cardiovascular risk, and higher mortality [

1,

2,

3]. Although more than 20 years have passed since biological therapy became a reliable treatment for PsA, disability and cardiovascular events in patients with PsA have not significantly decreased [

4].

In recent years, many authors have investigated the mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of PsA and have attempted to identify different biomarkers that are associated with joint inflammation, the rate of joint destruction, the causes of accelerated atherosclerosis, and the effect of therapy in these patients [

5,

6,

7]. Many of these studies have implicated proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, enzymes, and antimicrobial proteins involved in different stages of disease development, each adding to the motley mosaic of the puzzle called psoriatic disease.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is a heme-containing peroxidase abundantly expressed in neutrophils and, to a lesser extent, in monocytes [

8]. Its antimicrobial activity is due to the synthesis of various acidic products (e.g., hypochlorous acid) [

8,

9]. MPO plays a central role in the degradation of microbial proteins and the regulation of oxidative stress at sites of inflammation, such as the joints and skin of patients with PsA [

10,

11,

12]. MPO can oxidize high-density lipoprotein, leading to its dysfunction and deposition in atherosclerotic plaques [

13].

The abundant generation of oxidants by MPO is associated with tissue damage in patients with acute or chronic inflammation. MPO is involved in processes involved in cell signaling and cell interaction, which is why there is increased interest in its role in a wide range of inflammatory diseases [

13].

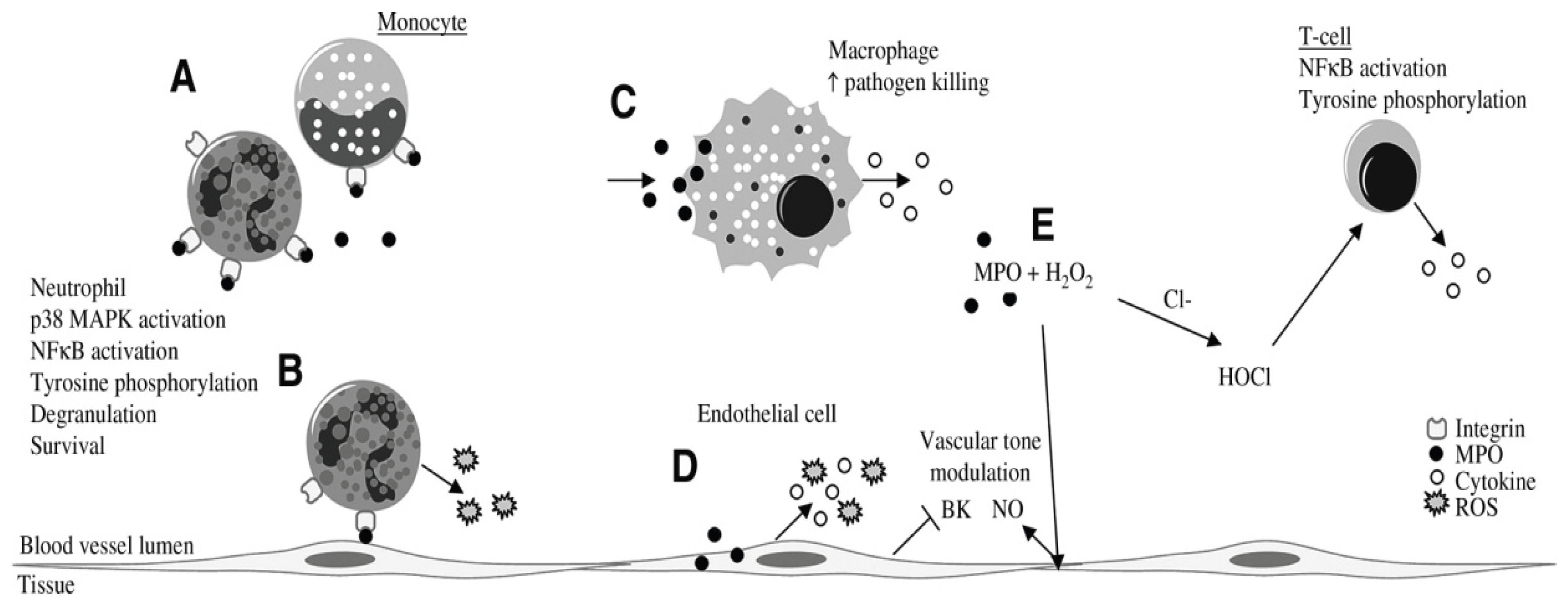

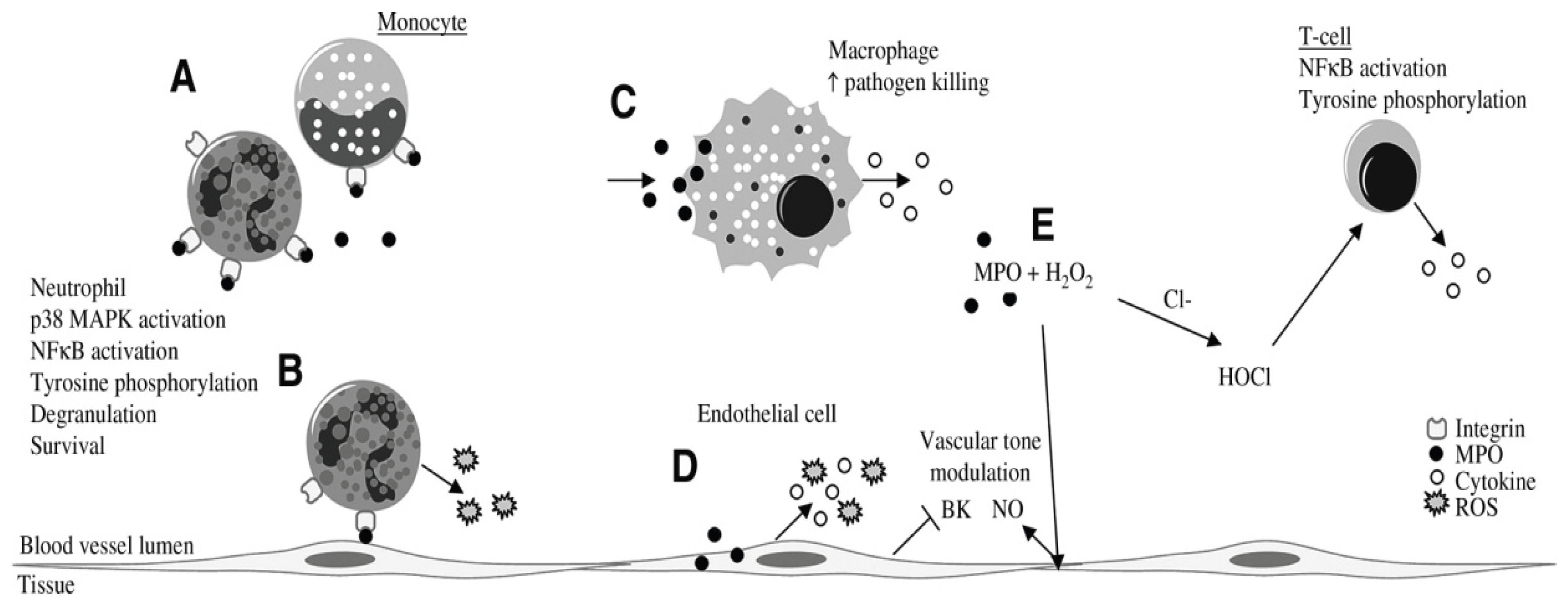

Figure 1.

Effects of MPO on inflammatory and endothelial cells. MPO can adhere to b2-integrins (CD11b=CD18) on neutrophils and monocytes (A). In neutrophils, MPO binding leads to activation of signal-transduction pathways (p38 MAPK and NF-kB), tyrosine phosphorylation, production of superoxide, degranulation, prolonged survival, and increased integrin expression (A, B), which can enhance neutrophil–endothelium interactions (B). MPO is taken up by macrophages, which leads to production of cytokines (TNF-a and IFN-g) and to increased pathogen killing (C). Endothelial cells internalize MPO, resulting in production of cytokines (IL-6 and IL-8) and ROS (D). In addition, MPO internalization by endothelial cells leads to inhibition of bradykinin (BK) (D), which, together with NO that is released as an indirect response to MPO (E), can modulate the vascular tone. In T cells, MPO-derived HOCl can induce NF-kB activation, tyrosine phosphorylation, and subsequent TNF-a production (E). [from van der Veen BS et al., 12].

Figure 1.

Effects of MPO on inflammatory and endothelial cells. MPO can adhere to b2-integrins (CD11b=CD18) on neutrophils and monocytes (A). In neutrophils, MPO binding leads to activation of signal-transduction pathways (p38 MAPK and NF-kB), tyrosine phosphorylation, production of superoxide, degranulation, prolonged survival, and increased integrin expression (A, B), which can enhance neutrophil–endothelium interactions (B). MPO is taken up by macrophages, which leads to production of cytokines (TNF-a and IFN-g) and to increased pathogen killing (C). Endothelial cells internalize MPO, resulting in production of cytokines (IL-6 and IL-8) and ROS (D). In addition, MPO internalization by endothelial cells leads to inhibition of bradykinin (BK) (D), which, together with NO that is released as an indirect response to MPO (E), can modulate the vascular tone. In T cells, MPO-derived HOCl can induce NF-kB activation, tyrosine phosphorylation, and subsequent TNF-a production (E). [from van der Veen BS et al., 12].

According to Schmitt et al., MPO indirectly activates nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) and tyrosine phosphorylation in T and B lymphocytes, leading to increased calcium signaling and increased production of tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-a) and low levels of interferon-g (IFN-g) in association with increased macrophage-dependent cytotoxicity [

13].

MPO is important for the clinical symptoms of various diseases. In experimental models, the authors have found that partial inactivation of MPO reduces clinical symptoms, such as joint swelling and erythema, which has not been studied in patients with PsA [

14].

According to Ray and Katyal, myeloperoxidase links inflammatory and oxidative mechanisms in various neurological diseases and leads to the release of neurotoxic mediators and peripheral inflammatory cells [

15]. According to the same authors, the importance of myeloperoxidase in neurodegeneration may offer new therapeutic and diagnostic opportunities for these diseases [

15].

Wakui demonstrated that MPO serves as a valuable marker for acute myelogenous leukemia [

16]. According to the author, MPO+ expression on myelogenous leukemia cells is associated with favorable outcomes and can be used as a prognostic biomarker in this disease.

MPO is considered an important biomarker in cardiovascular diseases [

17,

18,

19]. Authors have found elevated MPO levels in acute coronary syndrome, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, etc., and that high serum MPO levels are a predictor of future cardiovascular events and adverse outcomes in these patients [

18,

19].

According to Mahat et al., prediabetic patients affected by adverse cardiovascular outcomes had high MPO levels [

19]. The same patients had elevated blood pressure, elevated body mass index, and dyslipidemia [

19].

Among the classical rheumatological diseases, anti-MPO antibodies have been studied in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and have been shown to be present in various variants of lupus, as well as in polyangiitis, nephritis and vasculitis [

20,

21]. According to Telles, higher plasma levels of MPO have been found in patients with SLE compared to healthy patients, although this does not correlate with the severity of the disease [

21].

Cretu et al. studied various biomarkers that can differentiate psoriasis from PsA and demonstrated that, compared to controls, the level of serum MPO is independently associated with PsA and skin psoriasis, therefore it can be used as a biomarker in this disease in combination with other indicators [

22].

Modestino et al., who studied pathomorphological changes in patients with PsA [

23], have a different opinion. According to the authors, activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes from patients with PsA show reduced activation, reduced production of oxygen radicals and impaired phagocytic activity upon stimulation with Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF). In the same patients, reduced MPO release was observed. At the same time, the level of MPO in the serum of patients was increased. According to Modestino et al., polymorphonuclear leukocytes have an “exhausted” phenotype, highlighting their plasticity and multifaceted roles in the pathophysiology of PsA [

23].

Li et al. described the formation of extracellular neutrophil traps (NETosis) in patients with PsA [

24]. The authors investigated the association of MPO-DNA levels with indices of disease activity and found an increased serum MPO-DNA level compared to healthy controls (p < 0.001), as well as a positive correlation with the studied indices of disease activity [

24].

Despite the undeniable importance of MPO for a number of cardiovascular, neurological and rheumatological diseases, there are still unresolved issues related to the concentration of MPO in various tissues and fluids, as well as correlations with clinical symptoms and disease activity in patients with PsA [

24,

25,

26]. The aim of the present study is to determine the serum level and the level in the synovial fluid of MPO in patients with PsA compared to a control group of healthy individuals and patients with GoA (1), the expression of MPO+ cells on the synovial tissue of patients with PsA and GoA (2), the correlation between the level of MPO in various fluids with indices of disease activity in patients with PsA (3) and the creation of regression models using MPO results in different structures as an independent variable (4).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Study and the Patients

This observational study was conducted between October 2021 and March 2025. All the patients signed an informed consent form upon inclusion, and the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Plovdiv approved the study (Nr. 5/ June 2021). The results are related to the project No. NO-07/2025 of the Medical University of Plovdiv, Bulgaria. The study respected the declaration of Helsinki regarding human studies and was in accordance with the Ethics Code of the World Medical Association. The inclusion criteria in this study were, besides the informed consent of the patients.

The study, involving 36 patients with a PsA diagnosis according to the CASPAR criteria and 42 patients with GoA. The control group included 30 healthy individuals, similar in gender and age to the patients. All participants were diagnosed and treated in the Departments of Rheumatology at the University General Hospital “St. George” and the University General Hospital “Kaspela” in Plovdiv, Bulgaria. The inclusion criteria for the PsA patients were: (1) proven PsA arthritis with active synovitis of peripheral joints and axial involvement; ( 2) PsA non treated with a biological agent (TNF-α-blocker, IL (interleukin)-17 blockers, Il-12/23 blockers); (3) absence of mental health comorbidities; (4) signed informed consent form for participation in the study. The exclusion criteria for the PsA patients were: (1) patients diagnosed with other acute or chronic inflammatory or systemic diseases other than PsA (2) PsA treated with biologics and corticosteroids (3) decompensated cardiovascular, pulmonary or renal failure.

The patients with GoA were diagnosed according to the ACR criteria, 1991: (1) knee pain of at least 5 years, over 50 years of age, stiffness of less than 30 min, crepitations in the knee, deformity and enlargement of the joint, without warming; (2) radiographic evidence of osteophytosis of the knee joint; (3) erythrocyte sedimentation rate below <40 mm/h, negative rheumatoid factor; (4) signed informed consent form for participation in the study. Excluded were patients with: (1) presence of crystalline arthropathy; (2) presence of decompensated cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, or hematological diseases.

Serum samples were taken in the morning from all patients. The samples were processed, stored and tested according to the protocols specified by the company providing the kits for this study.

2.2. Procedure for Evaluation of Serum MPO

MPO was quantified using an ELISA kit with catalog number: E-EL-H1251 and product size: 45D/36T/24G from Elabscience. The sensitivity of the kit is 1.38 ng/ml, with a range of detection 0.63–100 ng/mL. Patient plasma was collected using EDTA-Na2 as an anticoagulant. After the samples were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 1000 × g at a temperature ranging up to 8 degrees Celsius during the first 30 minutes after collection, the supernatant was collected for analysis.

2.3. Documentation of of Synovial Fluid Examination

Synovial fluid was obtained by arthrocentesis of the knee joint. In accordance with antiseptic guidelines, arthrocentesis of patients with PsA with hydrops of the knee joint, related to the activity of their main diagnosis, and arthrocentesis of patients with GoA with hydrops of the knee joint was performed by an experienced rheumatologist after voluntary signing of informed consent and explanation of the benefit of this manipulation for the patient. The synovial fluid thus obtained was frozen at -20 degrees and examined in compliance with all requirements of the manufacturer for the examination of synovial fluid by ELISA method.

2.4. Procedure for Evaluation of Synovial Tissue

Tissue material was taken by biopsy and examined immunohistochemically. From the obtained material, 72 tissue samples were made from 36 joints of patients with PsA and 100 tissue samples from 42 knee joints of patients with GoA. The samples were collected, processed and analyzed according to the instructions for immunohistochemical evaluation of MPO+.

The synovial tissue preparations were processed and prepared in the Immunology Laboratory of the Institute of Reproductive Biology at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, and the results were analyzed by the Department of General and Pathological Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Medical University – Plovdiv. Each tissue sample was evaluated by two experienced histologists. The immunohistochemical reaction was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions using the Novolink Polymer Detection System. The reaction was considered positive when there was a brownish stain [

27]. The following values were used for the intensity of the staining: 0 - absent; 1 - weak; 2 - moderate; 3 - strong. Strong intensity was considered as staining of the positive control and absent, as in the negative control [

28,

29]. For a more adequate assessment of the staining reaction, all materials were compared with a negative control provided by the Department of General and Pathological Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Medical University - Plovdiv. Histologists observe different areas of the cell (membrane, cytoplasm) depending on the localization of the antigen sought. Serial sections from each of the studied cases were tested with the antibodies used. For each series of antibody tests, a positive and negative control was prepared. The positive control is selected in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, the negative - according to a standard immunohistochemical procedure without adding the tested antibody.

After the preparations dry, the immunohistochemical reactions are examined and photographed with an Olympus BX 51 microscope, equipped with an Olympus C5050Z MP camera (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd) in JPG format.

To quantify the intensity of the immunohistochemical reaction, the gray density obtained by converting the brown color reaction to black and white was measured using Adobe Photoshop v.7.01 (Adobe Systems Inc.) and Image Tool v.3.0 under Windows (UTHSCSA, San Antonio, TX). Comparison of reaction intensities between sections was performed under the following requirements: reactions to occur simultaneously; test objects must be of the same section thickness; comparison of reactions between tissues of the same origin.

The percentage of positively stained cells was determined as follows: at 0-10% = 0; 10-39% = 1; 40-69% = 2; 70-100% = 3. All cases in which the number of cells with positive staining was more than 10% were considered positive.

2.5. Disease Activity Indices

Several scales generally accepted in rheumatology were used to assess disease activity, as follows:

Based on the Visual analog pain score (VAS), the patients were categorized into three groups: patients with moderate pain (40–60 mm), patients with severe pain (60–80 mm), and patients with very severe pain (>80–100 mm) [

16]. Based on the Visual analog pain score (VAS), the patients were categorized into three groups: patients with moderate pain (40–60 mm <), patients with severe pain (60–80 mm), and patients with very severe pain (>80–100 mm) [

30].

According to Disease Activity in PsA (DAPSA) score, disease activity was categorized into three groups: low activity ≤14; moderate activity >14 to ≤28; and high activity >28 [

31].

According to Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Score (PASDAI), disease activity categories were categorized into four groups: in remission <1.9; low activity >1.9 to 3.2; moderate activity >3.2 to 5.4; and high activity >5.4 [

32].

On the basis of modified Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index (mCPDAI), disease activity was categorized into three groups: low activity 1 to 3; moderate activity >3 to 9; and high activity > 9 [

33].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuously measured variables were tested for normality through the Shapiro–Wilk's test. The normally distributed data were described with means and standard deviations (SD), and comparisons were performed through an independent-samples t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), and analyzed through the Mann–Whitney U test. Correlations were assessed using Pearson correlation analysis. Multivariable regression assessed the individual impact of several confounding factors. All tests were two-tailed and the results were interpreted as significant at Type I error alpha = 0.05 (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Data About the PsA and GoA Patients and Serum and Synovial MPO Levels in PsA Patients Compared to GoA and Healthy Controls

PsA patients were significantly more male (n=21, 58.33%), with a mean age of 57.17 ± 9.44 compared to the observed female group (n= 15, 41.67%) with a mean age of 54.87 ± 4.56. Patients suffering from PsA had a significantly higher body mass index and a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia compared to GoA patients (

Table 1). None of the patients had received intra-articular or systemic glucocorticosteroids for at least 24 months before the study. One month before participation in the study and collection of biological samples, patients did not take any corticosteroids and NSAIDs. All were on a stable dose of methotrexate 10-15 mg weekly or Leflunomide 20 mg daily, as presented in Table.1.

3.2. Serum and Synovial Fluid MPO Levels

The serum MPO level in patients with PsA was 471.56±41.7 ng/ml, the serum MPO level in patients with GoA was 221.98±22.1 ng/ml, the difference between the two disease groups was significant (p=0.02). The serum MPO level in control subjects was 15.6±6.7 ng/ml, which was significantly lower than the groups of patients with PsA and GoA (p=0.01).

When analyzing the individual values, it was found that 4 patients with PsA (11.11%) had a serum level of 0.00 ng/ml. Patients with GoA have in 33.33%, and healthy individuals in 70.0% serum level of MPO 0.00 ng/ml, as the difference between the number of patients with zero serum level of MPO in patients with PsA is significantly lower than in patients with GoA and healthy controls (p=0.05).

The level of MPO in the synovial fluid in patients with PsA is 309.56±23.6 ng/ml, and in patients with gonarthrosis - 103.4±21.5 ng/ml, as the difference between the two groups of diseases is significant (p=0.05).

When analyzing the individual values, it was found that there were 2 patients with PsA (5.55%) who had a level of MPO in the synovial fluid of 0.00 ng/mL, while in patients with GoA they were 33.33%, and the difference between the number of patients with a zero level of MPO in the synovial fluid was significantly lower in patients with PsA compared to patients with no symptoms (p=0.01).

Table 2.

Special parameters analysis.

Table 2.

Special parameters analysis.

| Parameter |

Patients with PsA, n=36 |

Patients with GoА n=42 |

Controls

n=30 |

P |

| MPO serum (M+IQR) ng/mL |

471,56 (0-496) |

221,98 (0-292)

|

15,6(0-65)

|

*

**

|

| MPO synovial Fluid (M+ IQR) ng/mL |

309,56 (0-325.44) |

103,4 (0.0-128.44)

|

|

**

|

3.2. Expression of MPO+ Cells on the Synovial Tissue of Patients with PsA and GoA

Expression of MPO

+ cells on the synovial tissue of patients with PsA and GoA was studied in all studied patients, with 10 sections made from the tissue of each patient, analyzed by two experienced histologists.

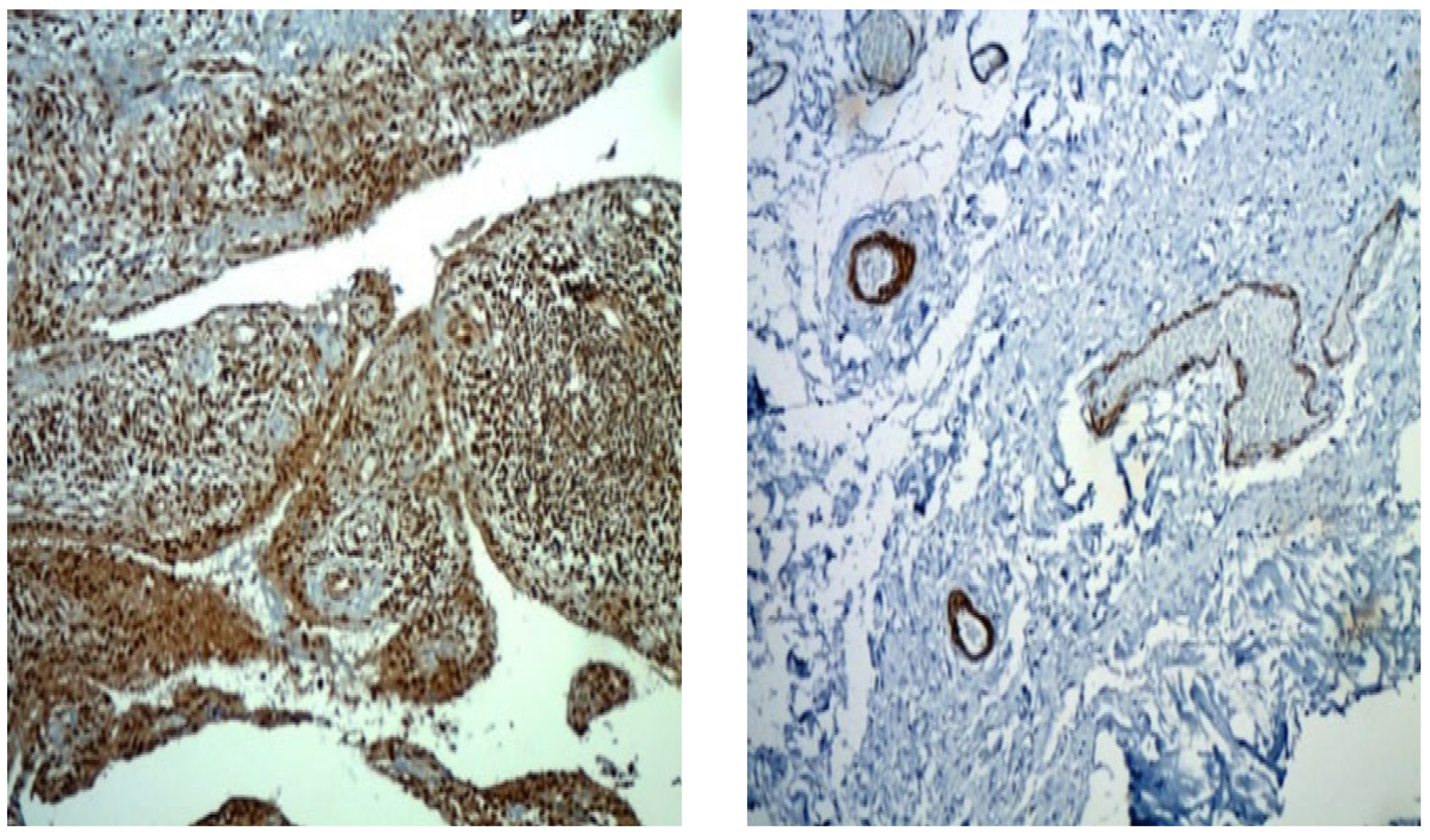

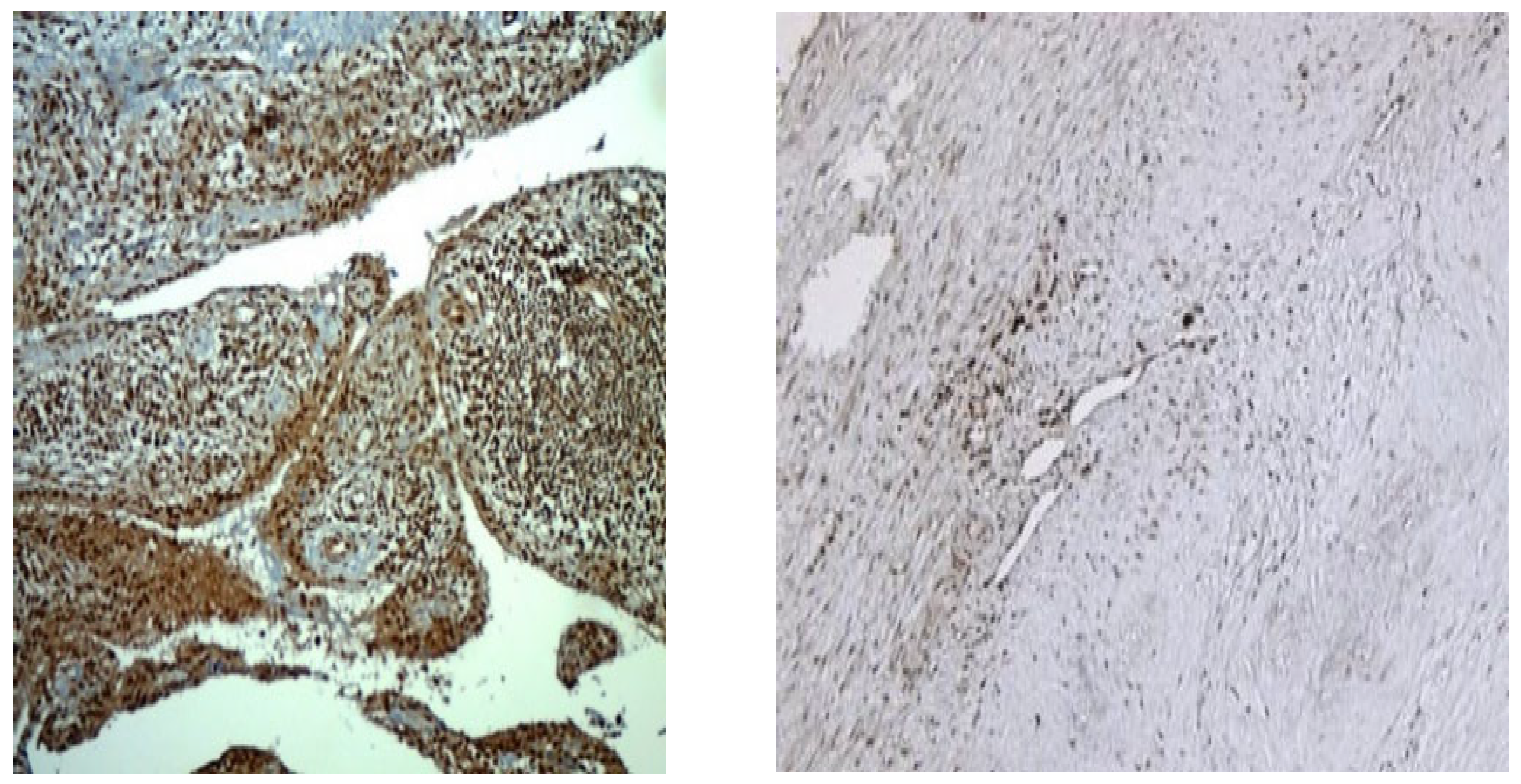

Figure 2 presents preparations of two patients with PsA with a disease duration of 10 years, on a stable dose of methotrexate treatment 15 mg per week, without intra-articular application of corticosteroid. The figure visualizes the representation of MPO

+ cells throughout the synovium, which differs quantitatively in the two patients.

MPUO

+ cells are presented differently in patients with PsA and GoA, as can be seen in

Figure 3. While in patients with PsA MPO+ cells are numerous, creating a strong signal and significant staining, in patients with GoA, the positive cells are few, single, and creating a weak signal with insignificant staining.

3.3. Correlation Between the Serum Level and Synovial Fluid Level of MPO with Disease Activity Indices in Patients with PsA

In all patients with PsA, the disease activity indices – VAS, DAPSA, PASDAI and mCPDAI were assessed.

According to the results, patients with very severe pain (>80–100 mm ) were 15 (35.71%). The serum level of MPO and the level of MPO in the synovial fluid of these patients were 502.84 (123.4-522.91) ng/mL and 341.35 (290.89-3561.44) ng/mL, respectively, which is significantly higher than patients with moderate pain (<40–60 mm), patients with severe pain (60–80 mm), as well as the control group of healthy subjects (P<0.01).

According to the results, patients with DAPSA high activity >28 score were 17 (40.47%). The serum MPO level and the synovial fluid MPO level of these patients were 492.76 (290.7-503.91) ng/mL and 91.22 (72.82-99.44) ng/mL, respectively, which was significantly higher than patients with low activity ≤14; moderate activity >14 to ≤28;, as well as the control group of healthy subjects (P<0.01).

According to the results, patients with PASDAI high activity >5.4 score were also 17 (40.47%). The serum MPO level and the synovial fluid MPO level of these patients were 492.53 (287.44-502.91) ng/mL and 111.30 (60.76-121.44) ng/mL, respectively, which was significantly higher than the patients in remission <1.9; low activity >1.9 to 3.2; moderate activity >3.2 to 5.4;, as well as the control group of healthy subjects (P<0.01).

According to the results obtained, patients with mCPDAI high activity >9 score were 15 (35.71%). The serum MPO level and the synovial fluid MPO level of these patients were 484.53 (273.33-497.91) ng/mL and 109.60 (55.76-119.54) ng/mL, respectively, which was significantly higher than the patients with low activity 1 to 3; moderate activity >3 to 9;, as well as the control group of healthy subjects (P<0.01).

Table 3.

Pearson Correlation was sought between disease activity indices and MPO levels (in serum and synovial fluid) in patients with high disease activity. It was found that patients with high disease activity according to the VAS, DAPSA, PASDAI and mCPDAI indices had significantly higher serum MPO levels in patients with PsA (p=0.01).

The same results showed that high MPO levels in the synovial fluid of patients with PsA correlated with higher serum MPO levels in patients with PsA, as well as disease activity indices (p=0.01) (

Table 4)

3.4. Creation of Regression Models for Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis Using MPO as an Independent Variable

In order to evaluate the relationships between the studied biomarkers, disease activity and their prognostic value in PsA patients, we conducted several multiple regression with the markers as independent variables. The results are presented in

Table 5.

5. Discussion

Despite extensive studies on various aspects of the pathogenesis of PsA, there are still contradictory data on the disease.

The aim of the study was to search for new biological markers related to serum and synovial changes in patients with psoriatic arthritis. If only serum markers are analyzed, this will not provide information about what is happening at the local (synovial) level and vice versa. Therefore, we searched for correlations between the clinical activity of psoriatic arthritis on the one hand and serum MPO and local changes (at the level of the synovial membrane) on the other hand to consider the problem in a multifaceted way.

We set ourselves the task of investigating the serum level and the level in the synovial fluid and synovial tissue of MPO positive cells in patients with PsA from the Bulgarian population, the correlation of these indicators with various composite indices of disease activity and assessing the possibility of using MPO as a diagnostic biomarker for differentiation from gonarthrosis.

According to Ray and Katyal, under the influence of IL-8, TNFα neutrophils infiltrate various tissues and catalyze inflammatory reactions, which leads to the release and activation of MPO to four groups: in remission <1.9; low activity >1.9 to 3.2; moderate activity >3.2 to 5.4; and high activity >5.4 [

15]. This has been demonstrated in atherosclerotic lesions in the endothelium of blood vessels, heart vessels, and the central nervous system. These processes have not been studied in patients with PsA, but given that the disease often occurs with various comorbidities such as arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, it was not surprising to find higher serum and synovial fluid levels of MPO in patients with PsA. Barone et al. studied the infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into damaged nerve tissue and demonstrated that polymorphonuclear leukocytes infiltrate sites damaged by focal ischemia, and then the subsequent inflammatory response can contribute to progressive tissue damage to four groups: in remission <1.9; low activity >1.9 to 3.2; moderate activity >3.2 to 5.4; and high activity >5.4 [

26]. According to the authors, the analysis of MPO is useful, as it could be used to clarify the potential harmful consequences of neutrophil infiltration into tissues [

26]. By analogy, this could also occur in damaged synovial tissue in patients with PsA, although there is no convincing evidence in the scientific literature for this.

We analyzed serum samples, synovial fluid samples and synovial tissue from 36 patients with PsA, 42 patients with gonarthrosis and 30 healthy controls as a pilot study, part of a project related to analyzing different aspects of the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis.

In our study, patients with PsA were significantly more male (58.33%), with a mean age of 57.17±9.44 compared to the observed group of women (41.67%) with a mean age of 54.87±4.561, which corresponds in terms of gender and age distribution to other studies [

1,

3].

Our patients suffering from PsA had a significantly higher body mass index and a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia, as reported by other authors [

1,

3].

According to the data obtained by us, the serum level of MPO in patients with PsA was 471.56±41.7 ng/ml, the serum level of MPO in patients with GoA was 221.98±22.1 ng/ml, and the difference between the two groups of diseases was significant (p=0.02).

In a comprehensive study by Cretu et al., it was found that there are many undiagnosed patients with PsA, as they remain unrecognized and are treated by dermatologists solely for psoriasis [

22]. The authors studied multiple biomarkers, one of which is MPO, and concluded that this biomarker can be used for diagnostic purposes. According to Cretu et al., the serum level of MPO is 418.1 ng/mL (270.9), in patients with psoriasis 402.5 (217.3) and in healthy controls 232.8 (126.6). Our data differ from those of the cited authors, but our data are based on studies obtained by ELISA methodology, while they conducted Mass-spectrometry based global proteomic studies on synovial fluid and skin biopsies [

22].

We studied the expression of MPO+ cells in the synovial tissue of patients with PsA and GoA, since the synovial membrane is the main site of pathological change in both diseases. We demonstrated that MPO+ cells are represented differently in patients with PsA and GoA. While in patients with PsA, MPO+ cells are numerous, producing a strong signal and significant staining, in patients with GoA, the positive cells are few, single, and producing a weak signal with negligible staining.

There are numerous publications in the scientific literature related to the study of macrophages as a potential biomarker for clinical efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis [

34].

According to Haringman et al., there was a significant correlation between the change in macrophage count and the change in DAS-28 (Pearson correlation 0.874, p<0.01). The change in activated macrophages explained 76% of the variation in the change in DAS-28 (p<0.02). The sensitivity of the biomarker to change was high in actively treated patients. The authors concluded that changes in synovial macrophages can be used to predict the possible efficacy of antirheumatic treatment [

34].

Hammitzsch et al. in 2024 demonstrated that IL26 production is increased in the synovial tissue of patients with seronegative spondyloarthropathies and this is due to the activation of CD68+ macrophage-like synoviocytes. Similar to our findings, the authors concluded that these studies offer new therapeutic options independent of Th17 pathways [

35].

Analyzing the correlation between the level of MPO in different fluids with disease activity indices in patients with PsA, we found that the disease activity indices – VAS, DAPSA, PASDAI and mCPDAI – correlate with higher serum and synovial MPO levels.

In order to evaluate the relationships between the studied biomarkers, disease activity and their prognostic value in PsA patients, we conducted several multiple regression and logistic regression models (as appropriate) with the markers as independent variables. Creating different regression models with the results of the disease activity indices, serum MPO level and synovial fluid level included in them, we proved that they are important for assessing disease activity. This would be important for monitoring therapy or for searching for new therapeutic options.