Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

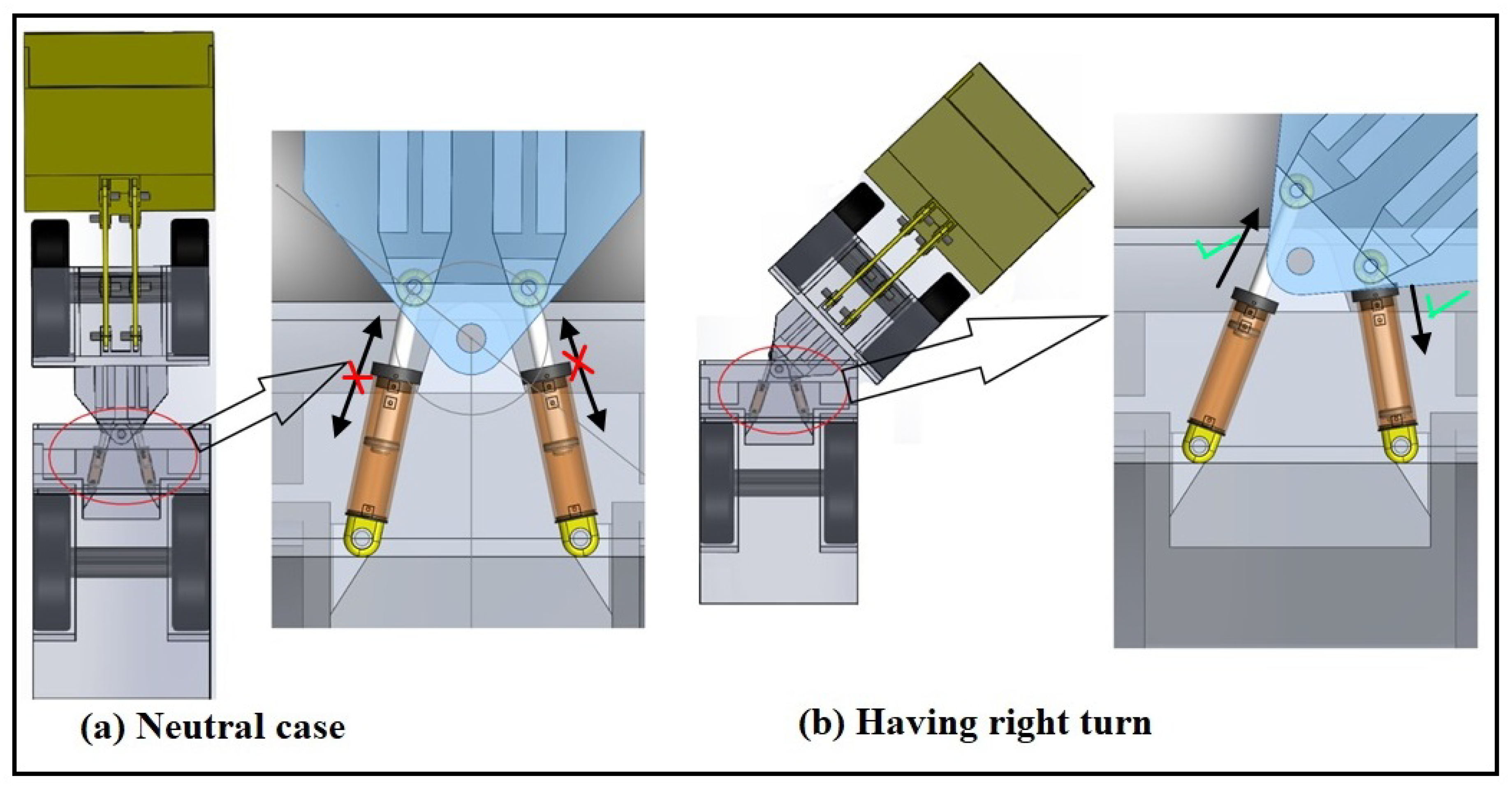

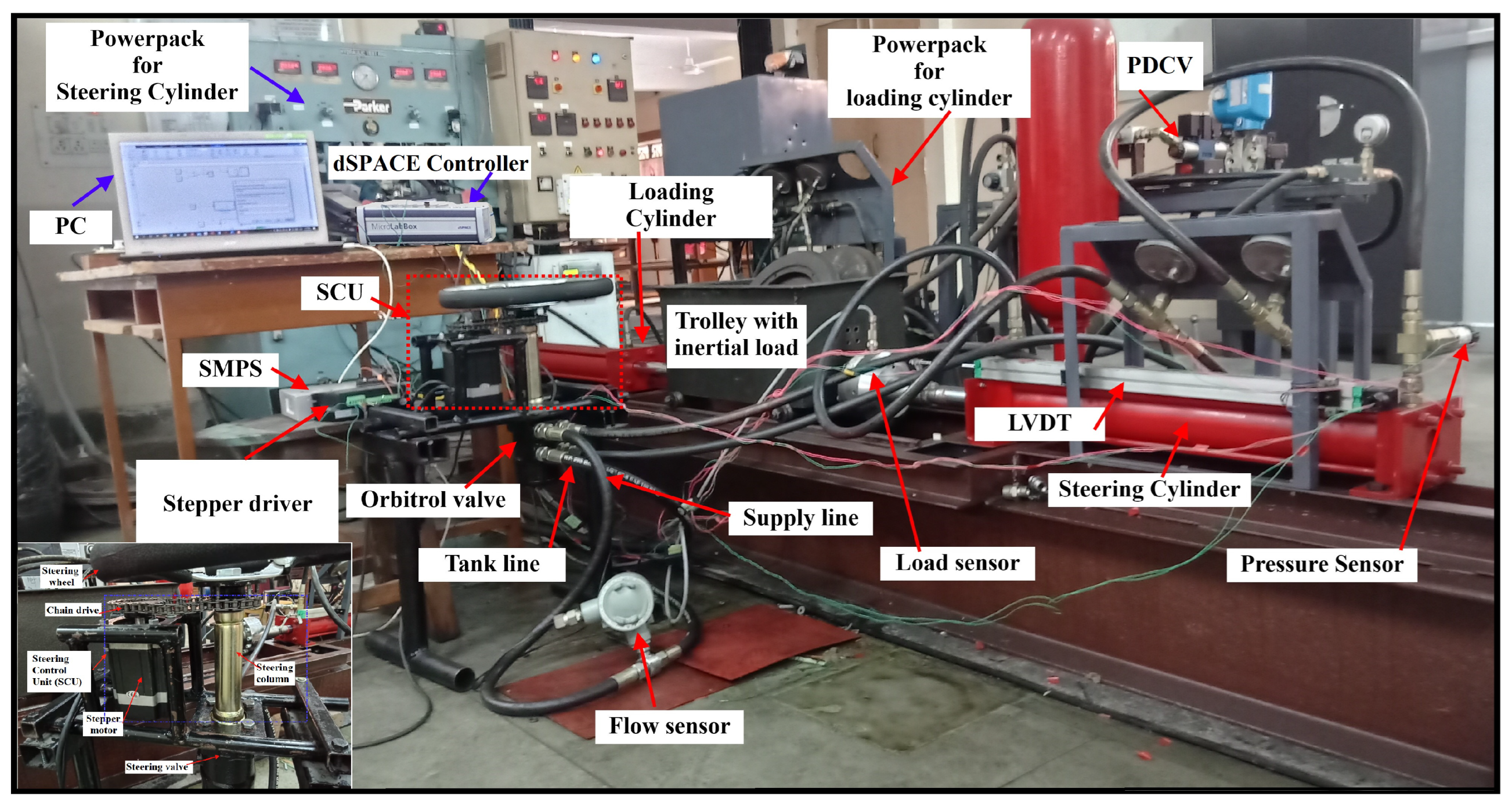

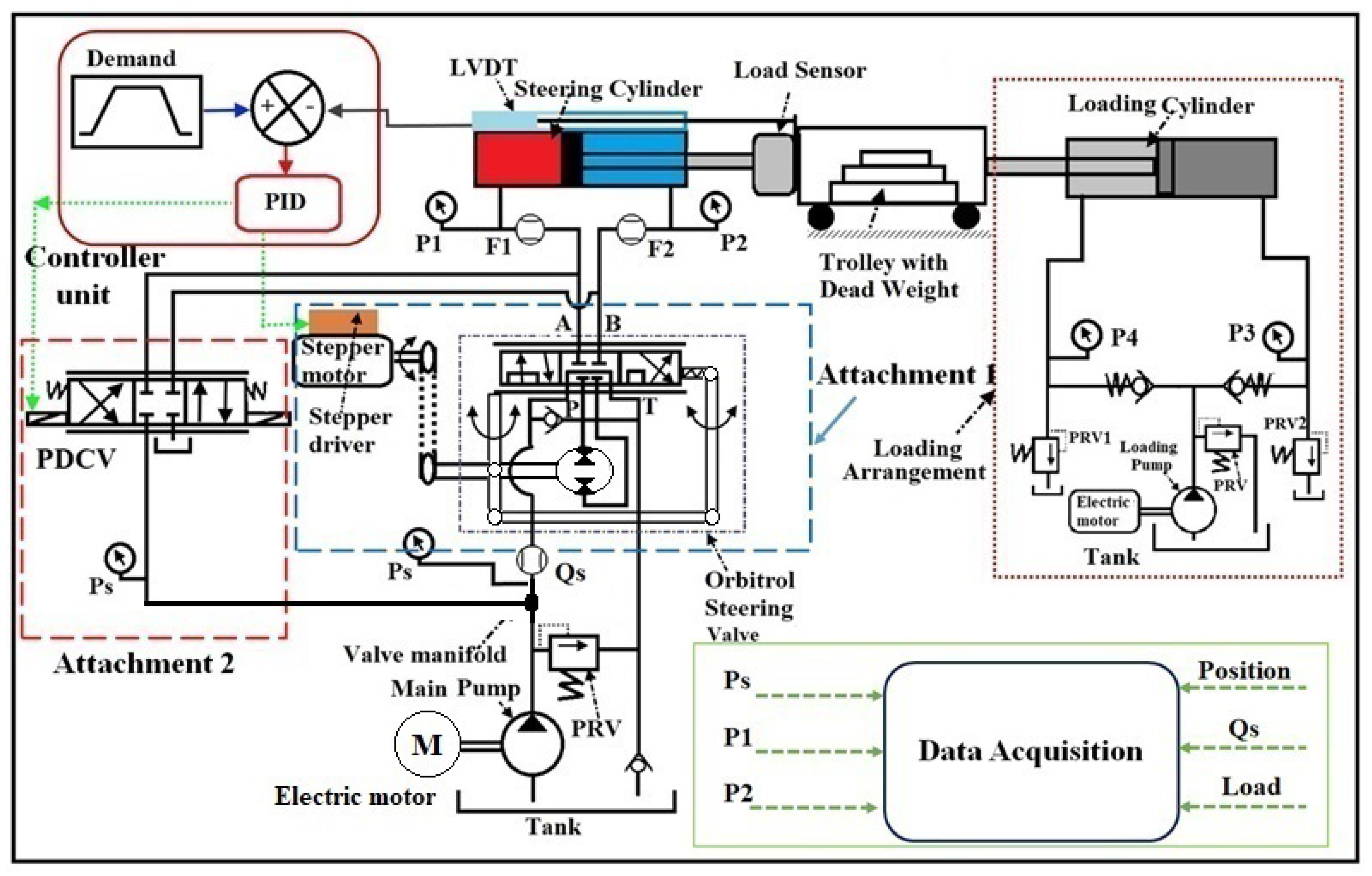

2. System Description

2.1. Functioning of the Test Rig

2.1.1. While Operaing with PDCV

2.1.2. While Operating with Orbitrol Valve

2.2. Experimentation Procedure

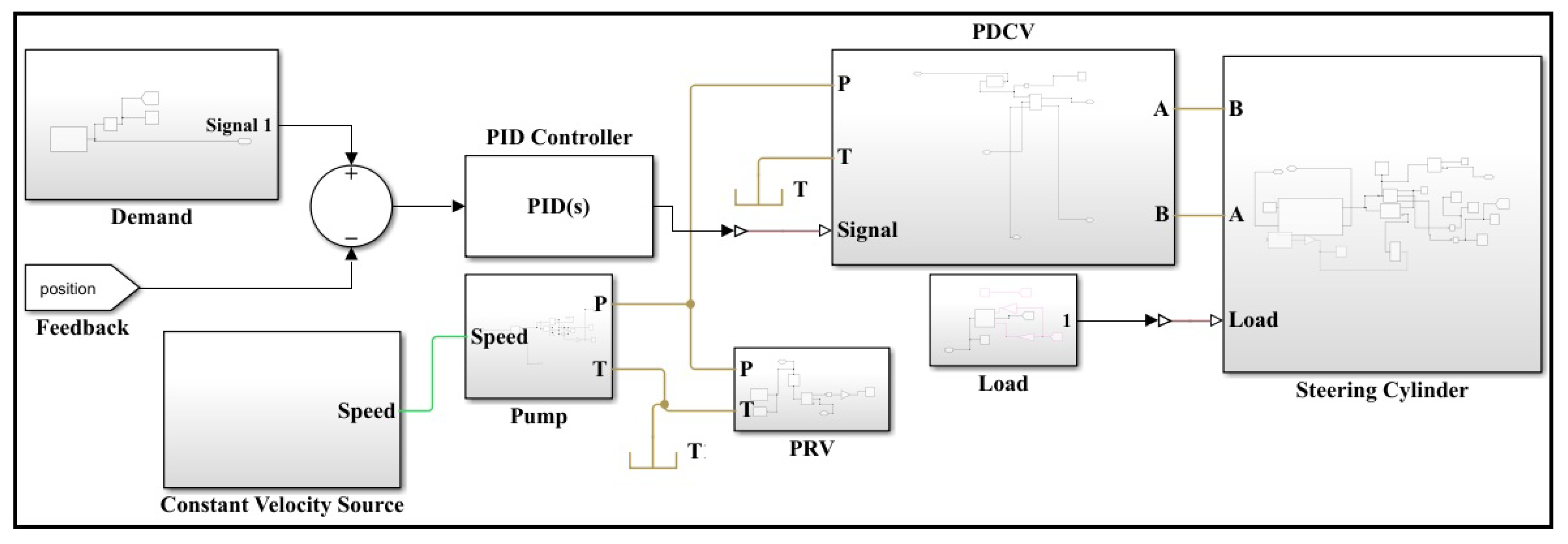

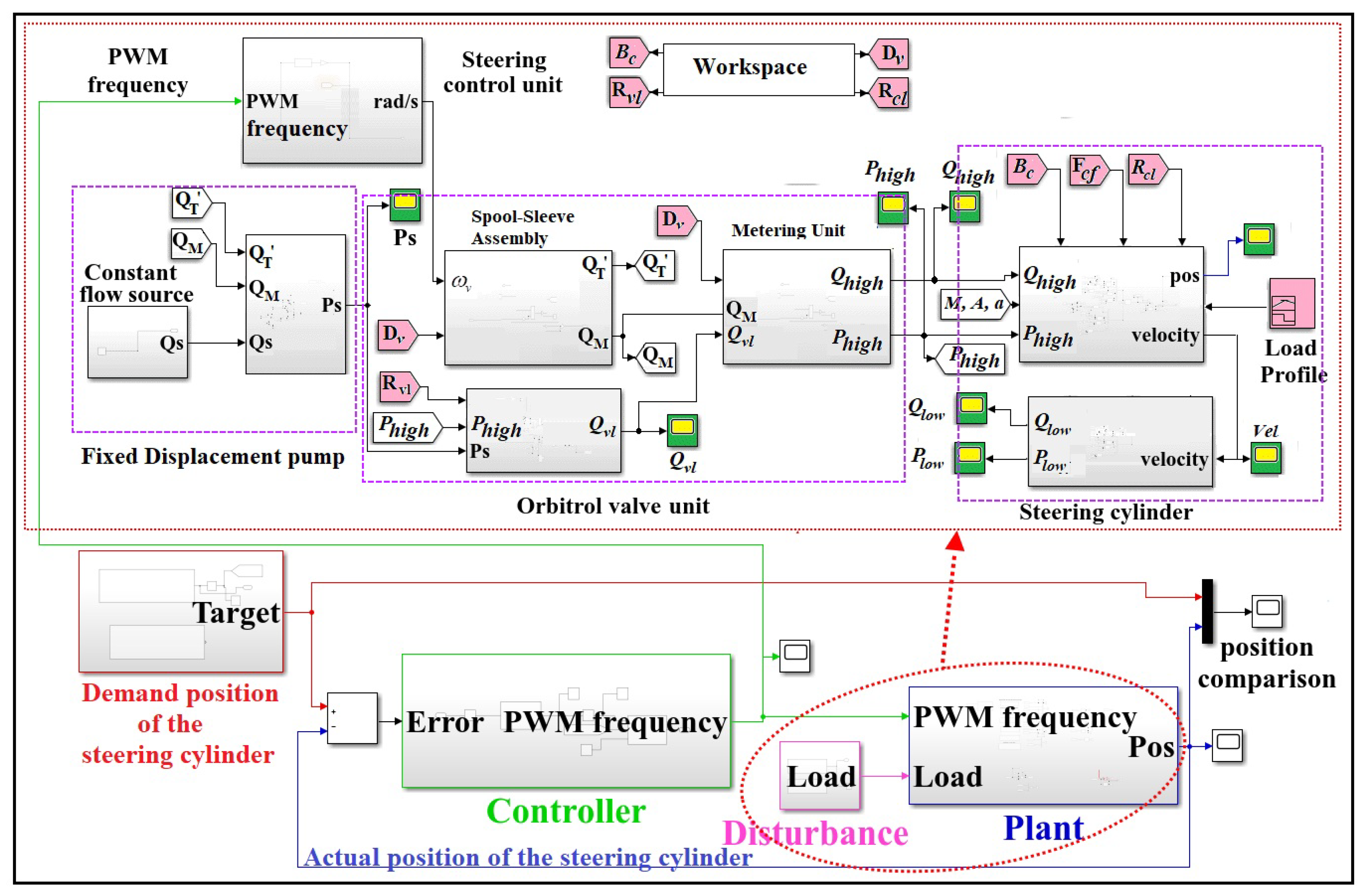

3. Mathematical Modeling and Development of Simulation Model

3.0.1. Equations for PDCV Valve

3.0.2. Equations for Orbitrol Valve

3.0.3. Equations for Steering Cylinder Unit

3.0.4. Equations for the Loading Unit

4. Results and Discussions

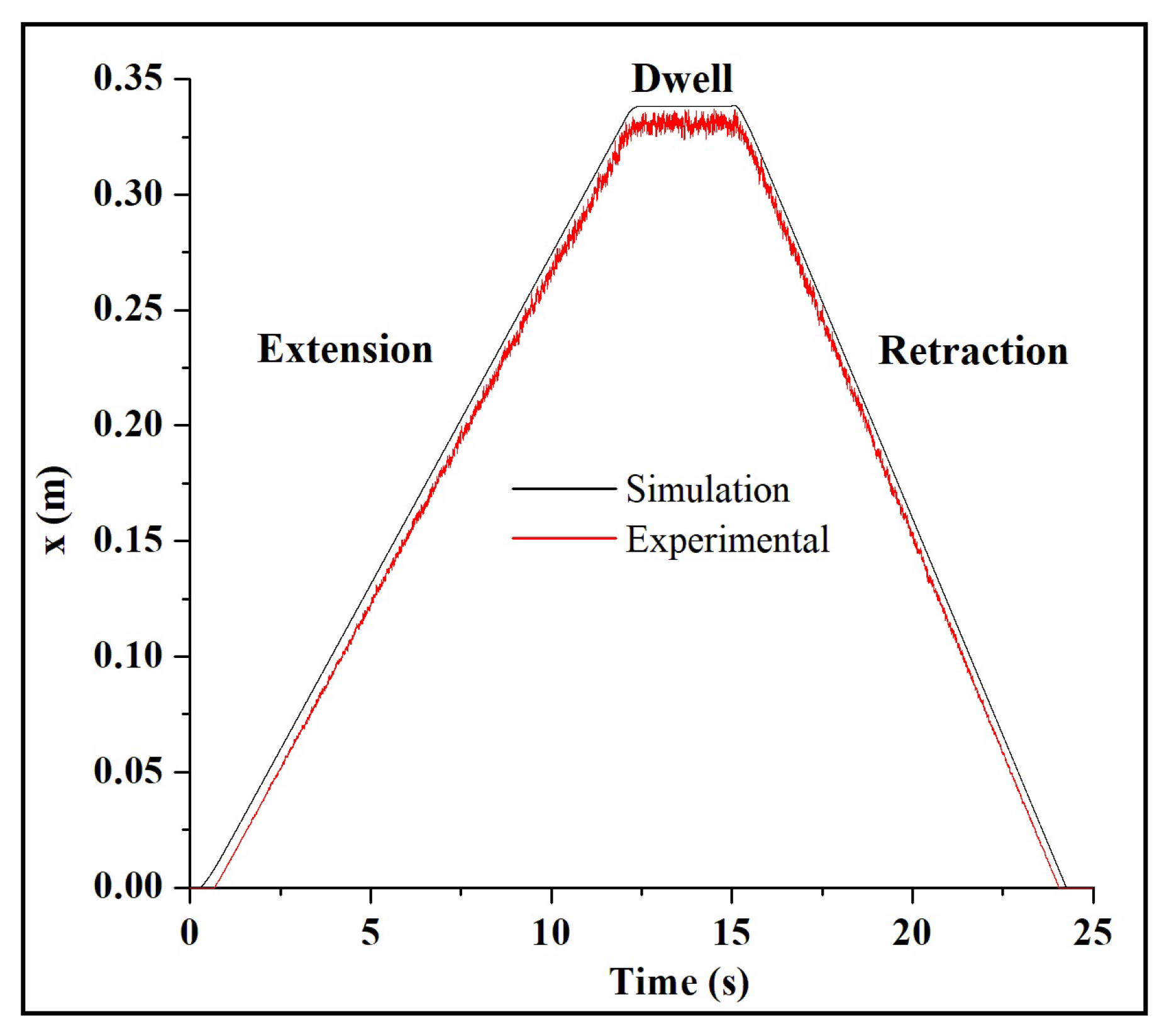

4.1. Validation of PDCV model

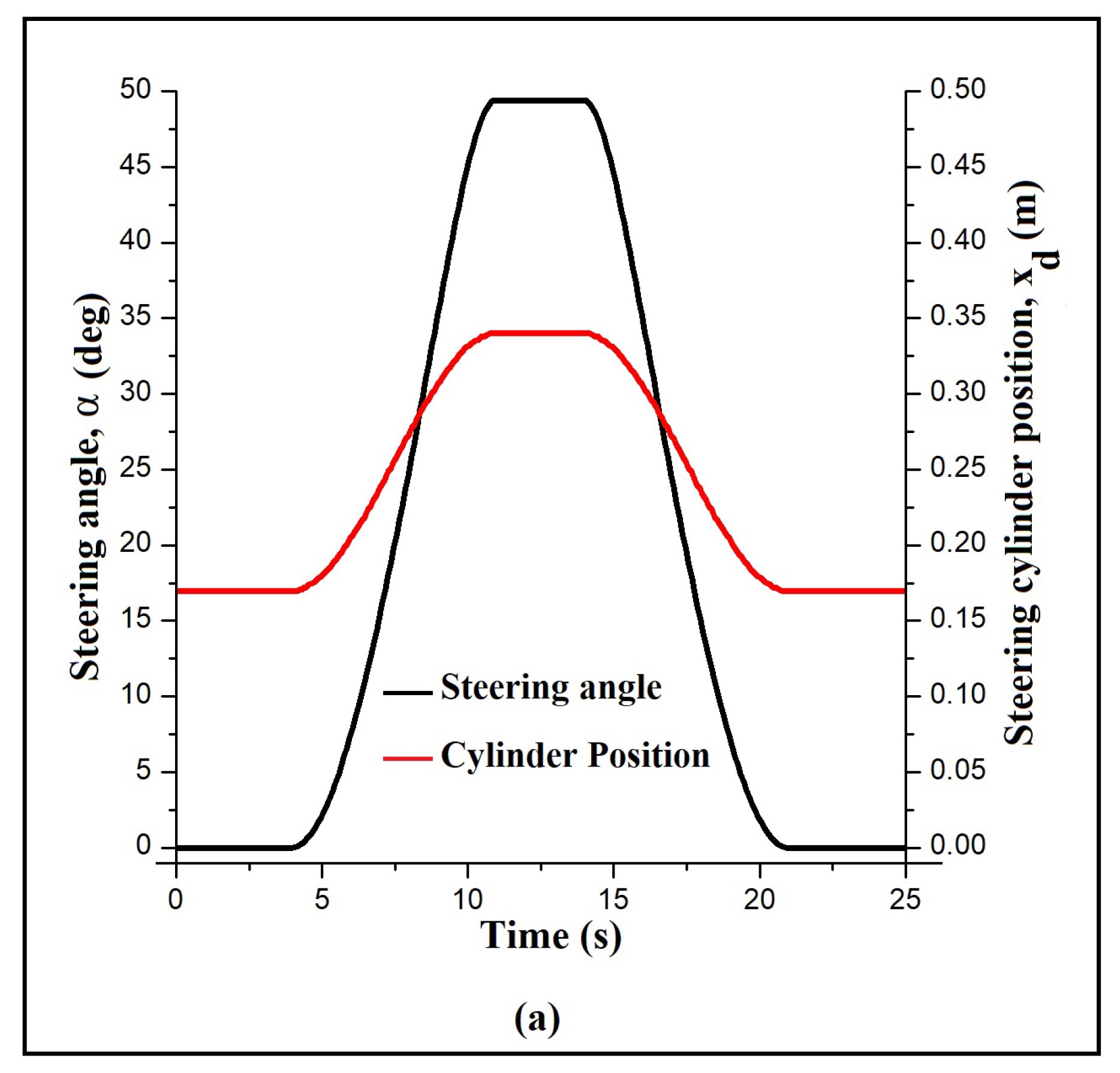

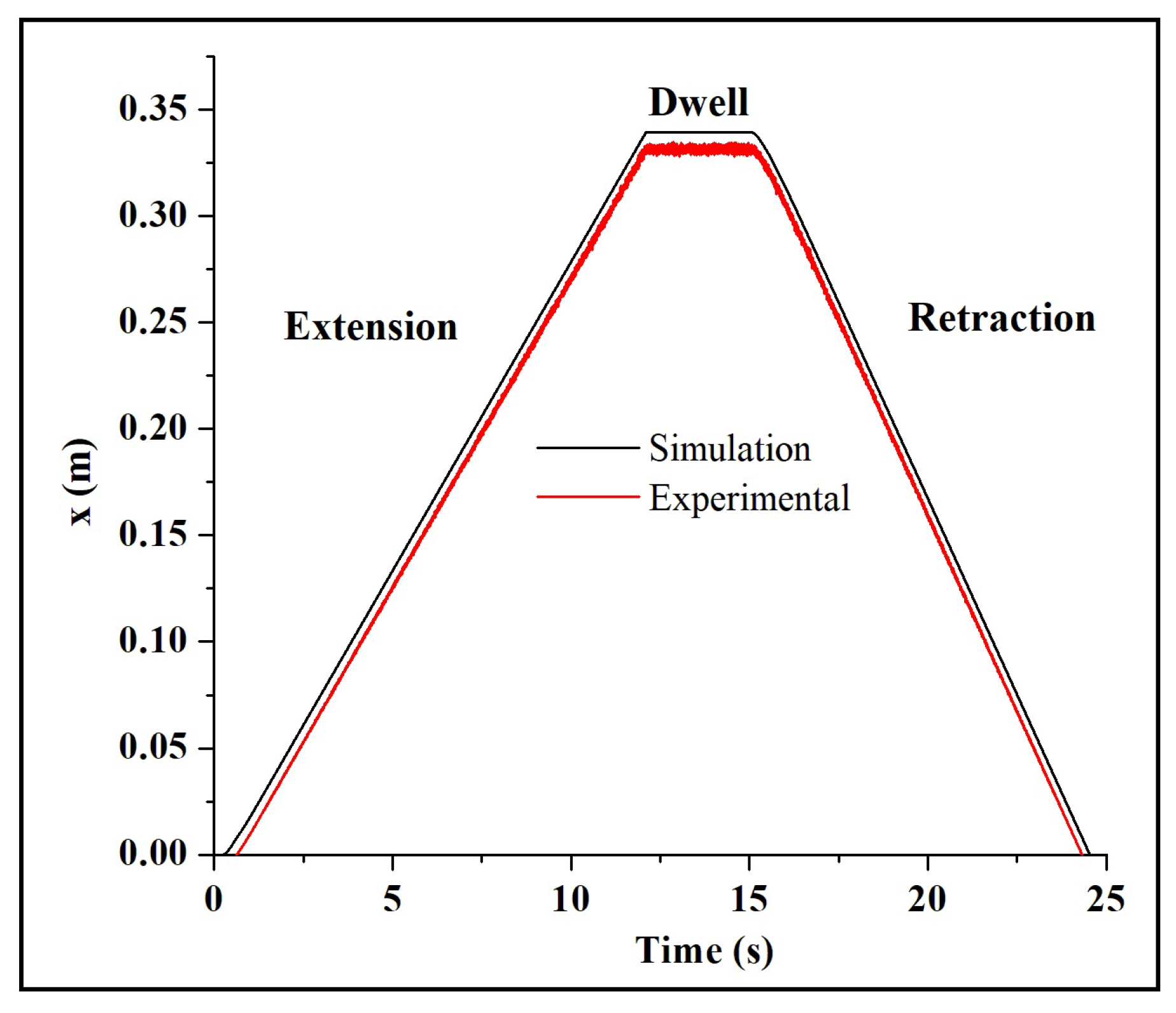

4.1.1. Position of the Steering Cylinder

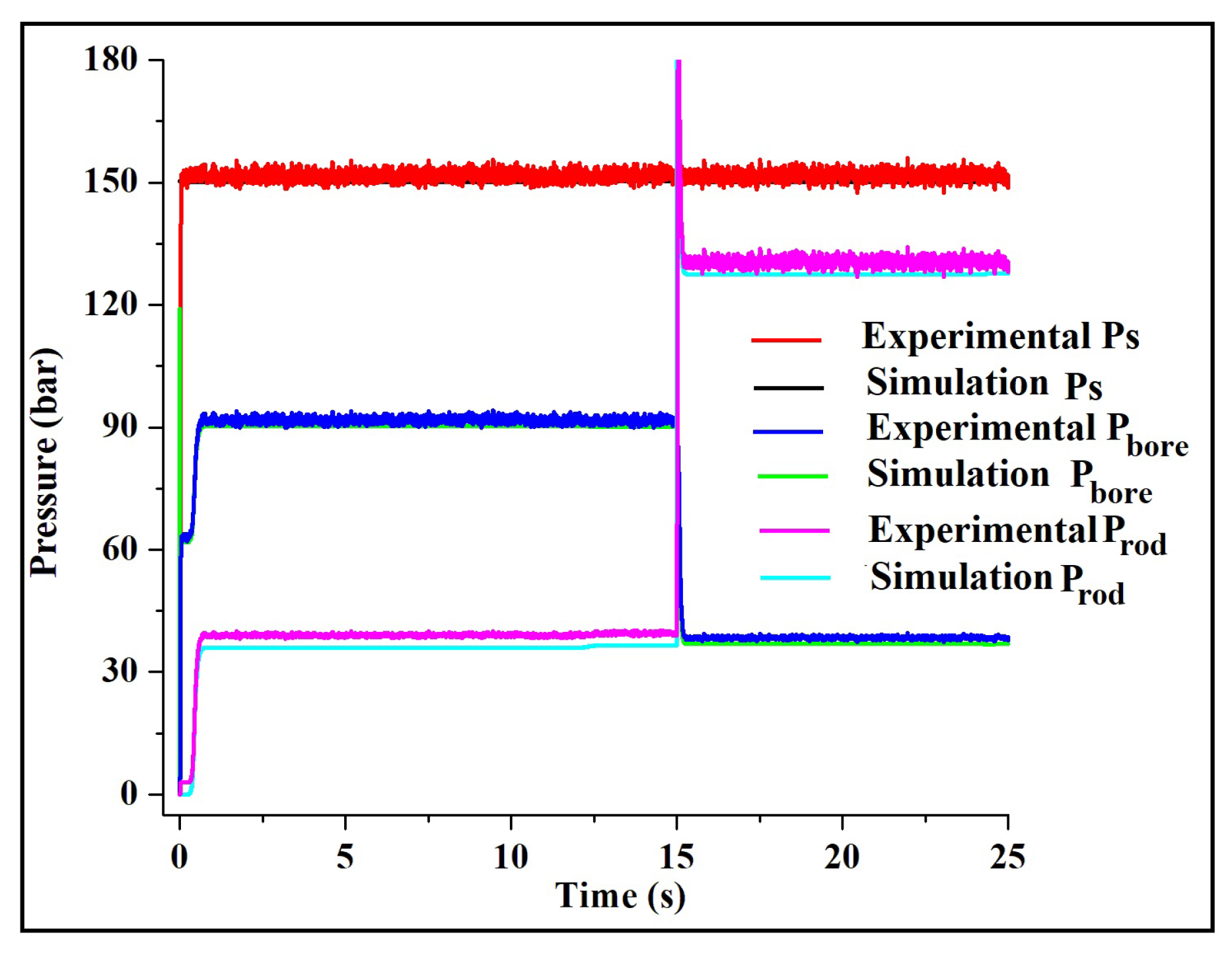

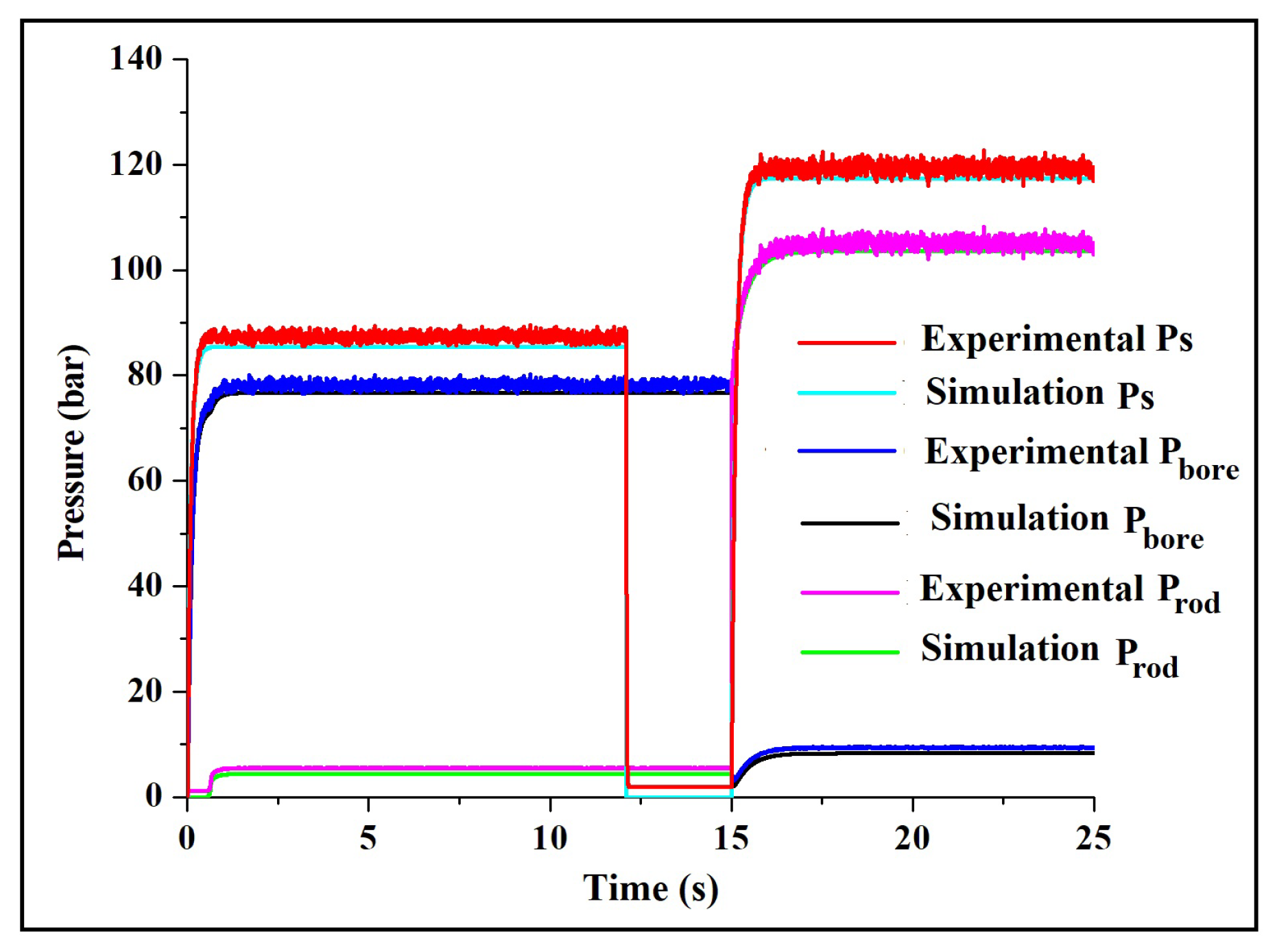

4.1.2. Pressure Across Different Lines

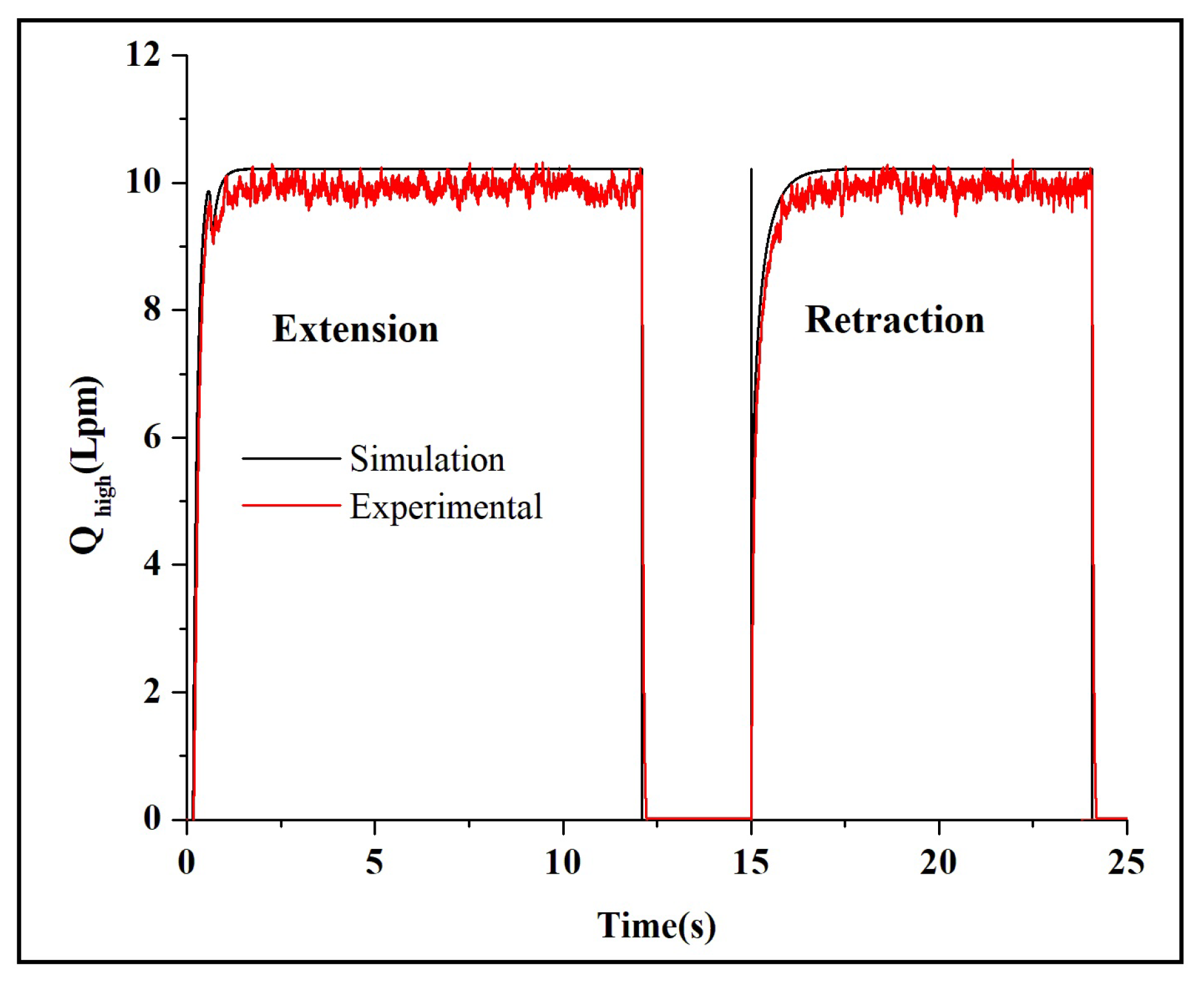

4.1.3. Flow Entering into the Steering Cylinder

4.2. Validation of Orbitol Model

4.2.1. Position of the Steering Cylinder

4.2.2. Pressure Across Different Lines

4.2.3. Flow Entering Into the Steering Cylinder

5. Comparison Analysis of PDCV and Orbitrol Valve

5.1. Estimation of the Demand Position

5.2. Comparison Analysis

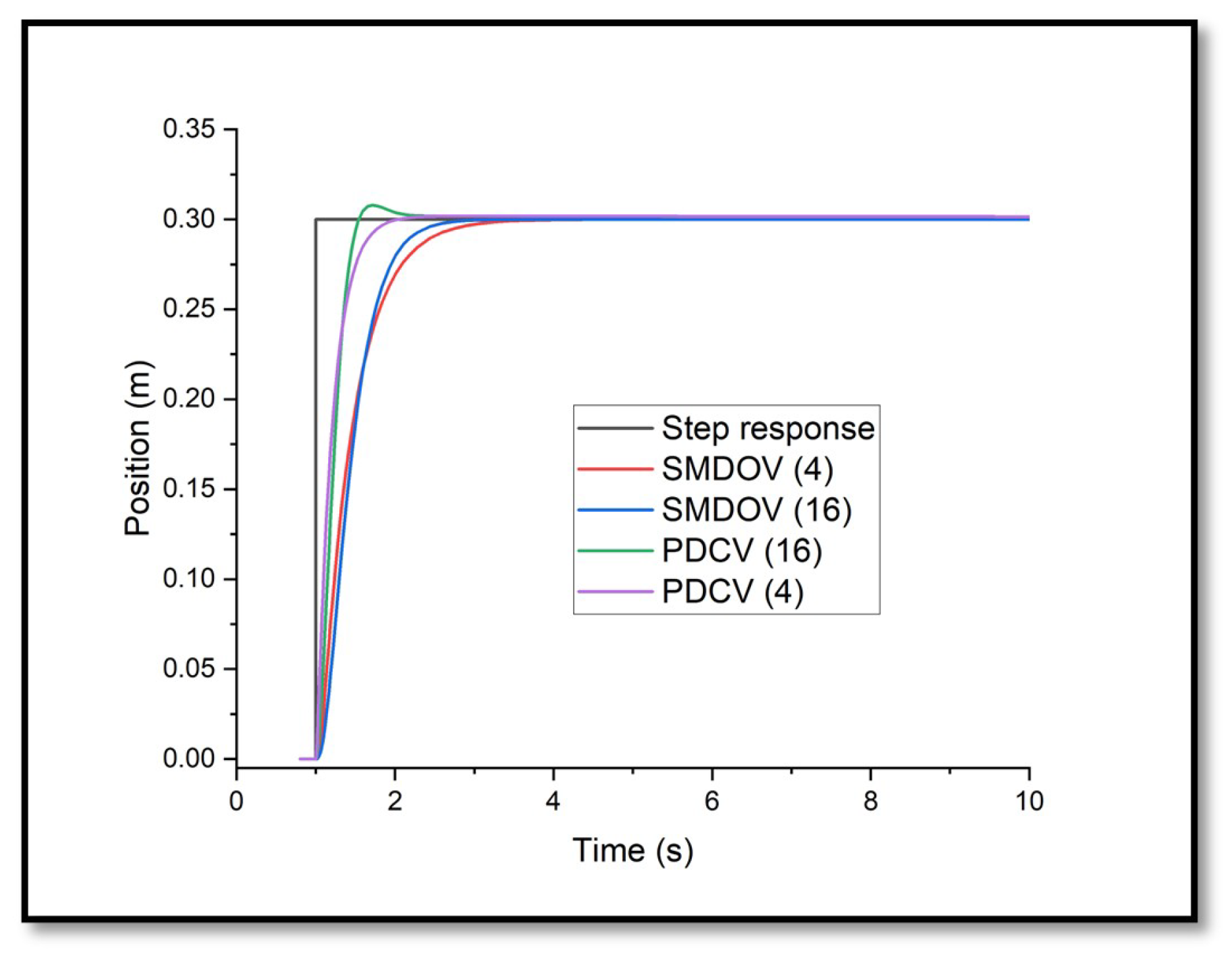

5.2.1. Step Response

5.2.2. Comparison of Steering Cylinder Position

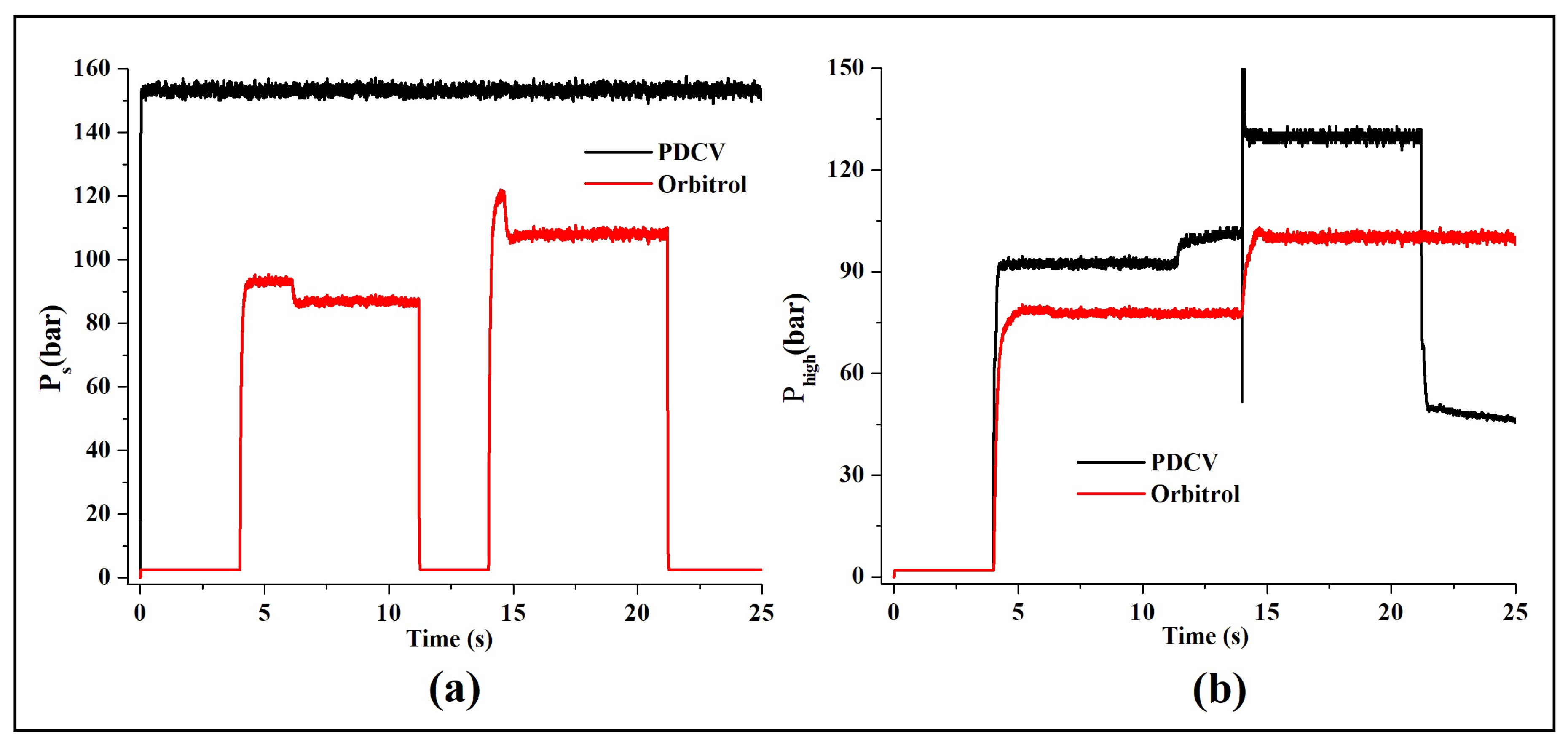

5.2.3. Comparison of Supply Pressure and Working Pressure

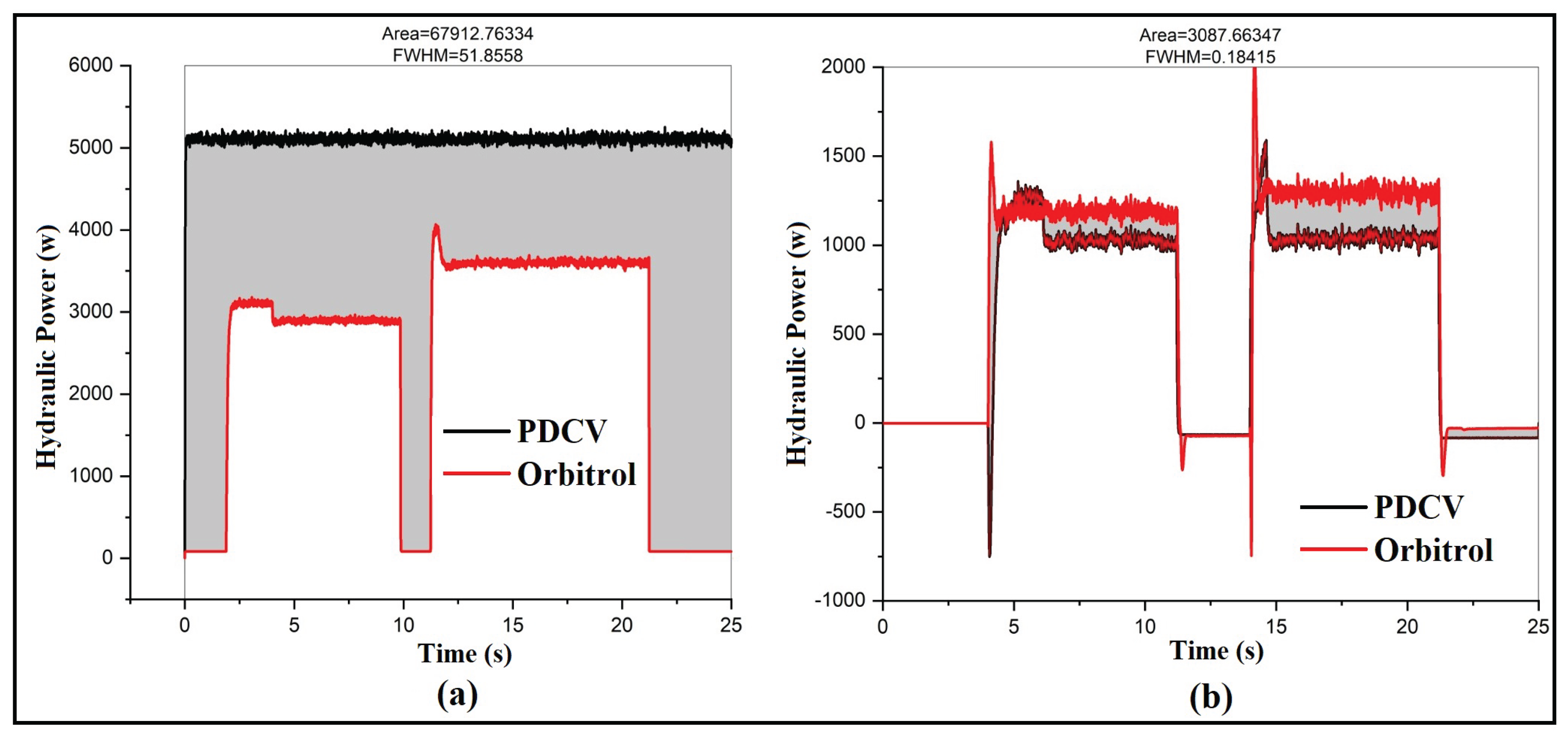

5.2.4. Energy Comparison

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Scope

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

| Type of the Sensors | Specific Details |

|---|---|

| Load Sensor | Load Range: 0 – 125 kN Output signal range: 0–10 V |

| Pressure Transducer | Pressure Range: 0–160 bar Output signal: 4–20 mA |

| Flow Sensor | Flow rate range: 0–30 Lpm Output signal: 4–20 mA |

| Linear Variable Differential Transformer (LVDT) | Output signal range: 0–5 V |

| Data Logger | HYDAC HMG 3000 model |

| Type of the Sensors | Specific Details |

|---|---|

| Power Pack (Electric Motor + Pump) | Angular speed of electric motor – 1000 rpm Displacement of the hydraulic pump – 20 cc/rev Volumetric Efficiency of the Pump – 0.92 |

| Orbitrol Valve | Displacement of the Valve – 200 cc/rev |

| Steering Cylinder | Bore diameter – 85 mm Rod diameter – 40 mm Stroke length – 340 mm |

| Viscous Loading Unit | Displacement of the Load pump – 12 cc/rev Angular speed – 1500 rpm |

| Load Cylinder | Bore diameter – 85 mm Rod diameter – 40 mm Stroke length – 340 mm |

| Hybrid Stepper Motor | Maximum torque – 9 N.m Step angle – 1.8 degrees |

| Flexible Hydraulic Hoses | Load-bearing Capacity – 250 bar |

| Notation | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| – | Hydraulic Oil | ISO VG 68 |

| Fluid Density | 850 kg/m3 | |

| Bulk Modulus | N/m2 | |

| Coefficient of Discharge | 0.64 |

References

- Tørdal, S.S.; Klausen, A.; Bak, M.K. Experimental System Identification and Black Box Modeling of Hydraulic Directional Control Valve. Model. Identif. Control 2015, 36. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Pizzo, P.; Rundo, M. Modelling and experimental studies on a proportional valve using an innovative dynamic flow-rate measurement in fluid power systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2018, 232. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Dai, Z.K.; Xu, X.Y.; Tian, L. Multi-domain modeling and simulation of proportional solenoid valve. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. (Engl. Ed. 2011, 18. [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Xu, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, X. A new kind of pilot controlled proportional direction valve with internal flow feedback. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2010, 23. [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, M. Full- and reduced-order model of hydraulic cylinder for motion control. In Proceedings of the Proceedings IECON 2017 - 43rd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, 2017, Vol. 2017-January. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jin, B. Analysis and modeling of a proportional directional valve with nonlinear solenoid. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2016, 38. [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Tao, G.; Luo, P.P. Dynamic analysis of proportional solenoid for automatic transmission applications. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Mechatronics and Control, ICMC 2014, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, Z.; Xu, B.; Su, Q. Investigation on the dynamic characteristics and control accuracy of a novel proportional directional valve with independently controlled pilot stage. ISA Trans. 2019, 93. [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Su, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Z. Analysis and compensation for the cascade dead-zones in the proportional control valve. ISA Trans. 2017, 66. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.Y.; Oh, D.H.; Ji, S.W.; Yun, S.N. Control of an overlap-Type proportional directional control valve using input shaping filter. In Proceedings of the Mechatronics, 2015, Vol. 29. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, K.; Ghoshal, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Das, J. Dynamic analysis of an open-loop proportional valve controlled hydrostatic drive. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2019, 233. [CrossRef]

- Bo, H.; Liang, W.; Yuefeng, D.; Zhenghe, S.; Enrong, M.; Zhongxiang, Z. Design and Experiment on Integrated Proportional Control Valve of Automatic Steering System. 2018, Vol. 51. [CrossRef]

- Rösth, M. Hydraulic Power Steering System Design in Road Vehicles : Analysis, Testing and Enhanced Functionality. PhD thesis, Linköping UniversityLinköping University, Department of Management and Engineering, The Institute of Technology, 2007. The printed version and the electronic version differ in that the electronic version contains two built in video films (see page 78 and page 89).

- Zardin, B.; Borghi, M.; Gherardini, F.; Zanasi, N. Modelling and simulation of a hydrostatic steering system for agricultural tractors. Energies 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A.; Nacif, G.C.L.; Cabezas-Goméz, L. Continuous Improvements Analysis in Energy Efficiency of Steering Power Systems to Light Vehicles. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 798. [CrossRef]

- Daher, N.; Ivantysynova, M. Energy analysis of an original steering technology that saves fuel and boosts efficiency. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 86. [CrossRef]

- Sreeharsha, R.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, A. Automatic control and stability analysis of a novel stepper motor-driven orbitrol valve operated articulated steering mechanism. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 375.

- Singh, V.P.; Olesen, E.N.; Pedersen, H.; Minav, T. Experimental evaluation of a novel electro-hydrostatic steering solution for off-road mobile machinery. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 332, 119710.

- Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Du, H.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z. Design and verification of a novel energy-efficient pump-valve primary-auxiliary electro-hydraulic steering system for multi-axle heavy vehicles. Energy 2024, 312, 133473.

- Amoruso, F.; Cebon, D. Brake-actuated steering control strategy for turning of articulated vehicles. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2025, 63, 424–454.

- Taheri, S. Steering Control Characteristics of Human Driver Coupled with an Articulated Commercial Vehicle. PhD thesis, Concordia University, 2014. Unpublished.

| Factors | PDCV | SMDOV |

|---|---|---|

| Steering Response | As the valve operates at high-pressure differences, the response of the valve is also relatively higher | Do not have a high response but enough for articulated steering purposes |

| Energy Efficient | Pressure losses are high. So, not an energy-efficient one | Pressure losses only when there is steering input, and it also provides a tandem sort of arrangement when there is no steering input. Hence, it saves a lot of energy and is an efficient one |

| Cost | Quite High | Not Costlier |

| Ease of usage | Easy for automation applications | Not easy for the automation of the steering system |

| Design | Relatively less complex | Design is quite complex |

| Mode of Operation | It is operated by supplying a voltage source of ±12V | Manual Operated using Steering Wheel |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).