1. Introduction

The high prevalence of chronic heart failure (CHF) in the population and mortality among patients [

1] determine the social significance of this disease. The prevalence of CHF is predicted to rise due to the increase in life expectancy of the population, the high prevalence of the main causes of CHF, as well as an increase in survival rate after acute cardiovascular events [

1]. Moreover, episodes of decompensated heart failure require emergency medical care or hospitalization, which significantly increases the economic burden of the disease. Despite the periodic implementation of new approaches to therapy, CHF is still associated with a high frequency of adverse outcomes and a significant deterioration in the quality of life of this category of patients [

1].

CHF is a syndrome that develops under conditions of imbalance of vasoconstrictor and vasodilating neurohormonal systems as a result of impaired ability of the heart to fill and/or empty and is accompanied by insufficient perfusion of organs and systems necessary for tissue metabolism. CHF is manifested by complaints of shortness of breath, weakness, palpitations, increased fatigue, and as the disease progresses, congestion [

2,

3]. Coronary artery disease (CAD) in 2/3 of cases is the main cause of CHF with a low ejection fraction and in almost half of cases - with a mildly reduced ejection fraction [

4].

Vascular disorders make a significant contribution to the development and progression of CHF. Structural vascular changes in both macro- and microvascular components of CHF include vascular remodeling (hypertrophy, fibrosis and changes in vascular smooth muscle function, reduction of the capillary density). Microvascular dysfunction is a determining factor in the development of ischemic heart failure, and coronary endothelial function plays a key role in the regulation of blood flow in both the epicardial and intramyocardial microcirculation [

5]. Functional impairment of the vascular system in CHF are primarily associated with endothelial dysfunction and systemic inflammation, which contribute to changes in vasomotor reactions and impaired tissue perfusion [

6].

Myopathy in elderly patients with CHF is associated with decreased physical performance, which can be explained by reduction of capillary density and impaired vasodilatory responses in skeletal muscles [

7]. This decrease in microcirculatory function further complicates the overall clinical course of CHF, exacerbating symptoms such as fatigue and exercise intolerance.

These factors underlie the search for additional effective methods of treatment for this category of patients, which can increase the overall effectiveness of treatment of patients with ischemic CHF when added to standart conservative and invasive strategies.

Enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) is used in the treatment of patients with CAD, including those complicated by the development of CHF [

8]. The advantages of EECP are its non-invasiveness and safety. The positive effect of EECP on the left ventricle (LV) systolic function, exercise tolerance and quality of life in patients with CAD, including those with systolic dysfunction, has been proven [

9,

10]. However, the long-term effects of EECP treatment on the morphofunctional state of the vessels, which are the main target of this method of treatment and an important component in the pathogenesis of CAD and CHF, have not been sufficiently investigated.

Aim. In this study, we aimed to study the vascular effects of long-term complex treatment, including EECP, in patients with CHF of ischemic genesis, and the relationship of these effects with clinical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

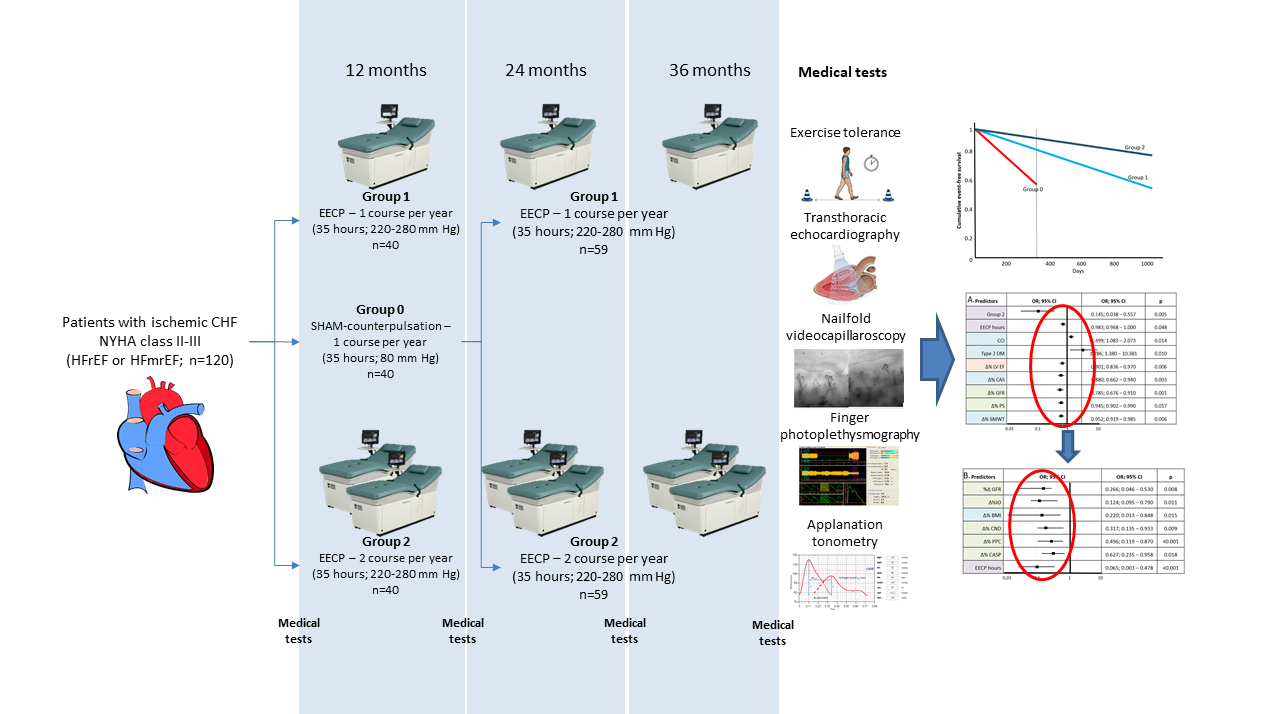

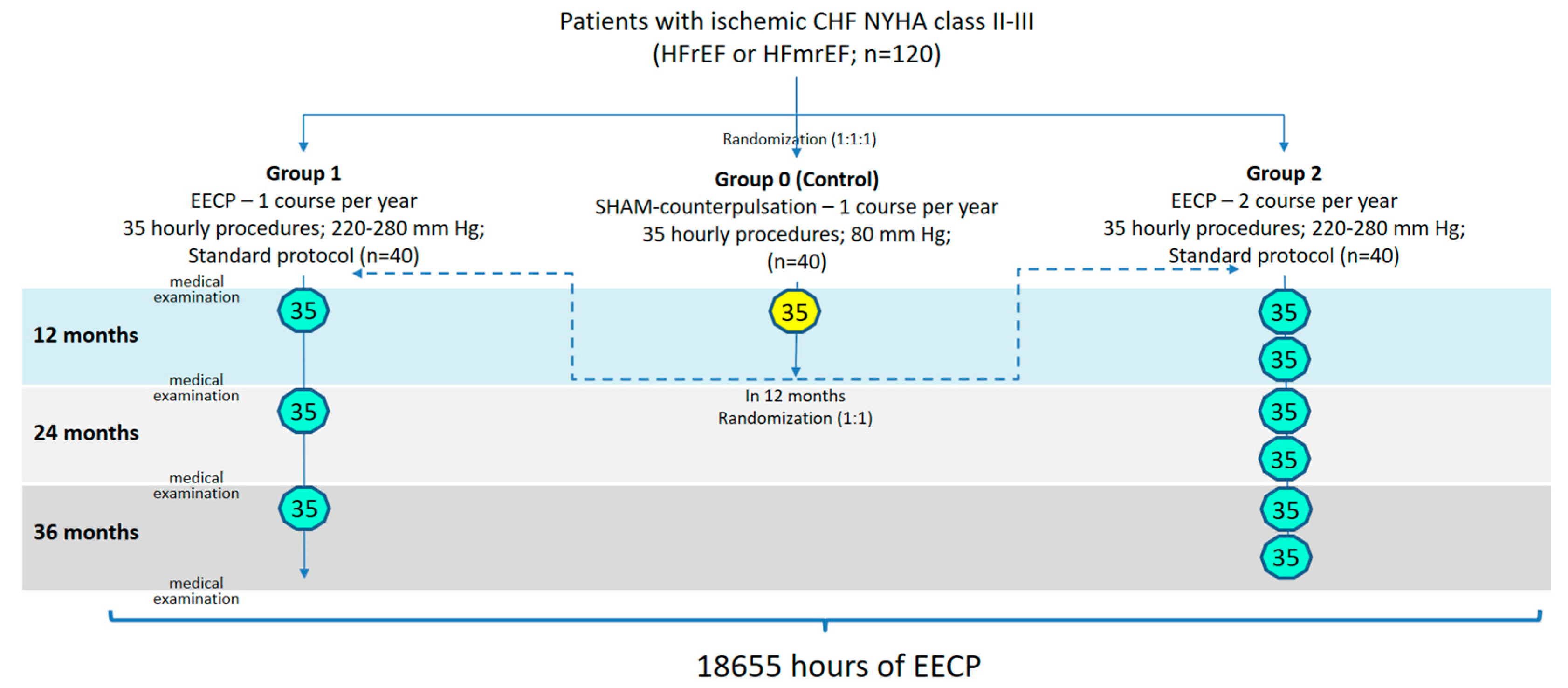

The open-label, randomized, placebo-controlled EXCEL (Long-term Effects of enhanced eXternal CountErpuLsation; NCT05913778) study included 120 patients with CAD, complicated by CHF (with reduced or mildly reduced LV ejection fraction [EF]), aged 40 to 75 years, who did not meet the exclusion criteria and signed informed consent [

11]. All patients had been receiving optimal medical therapy (OMT) for CHF and CAD for at least 3 months at the time of inclusion. The study protocol was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Sechenov University. Patients were randomized into three equal groups (1:1:1). In the first stage after randomization, the long-term (12 months) effects of EECP therapy were studied in comparison with placebo counterpulsation.

Patients in group 1 (n=40) received one course of EECP annually (35 sessions of 60 minutes, 5 times a week for 7 weeks; compression pressure 220–280 mmHg) in addition to OMT. Patients in group 2 (n=40), along with OMT, underwent two similar courses of EECP annually with an interval of 6 months. The control group (Group 0; n=40) received an annual course of placebo counterpulsation with a subtherapeutic level of compression (35 procedures of 60 minutes, 5 times a week for 7 weeks; compression pressure 80 mmHg) in addition to OMT.

The second stage if the study involved studying the effects of long-term EECP therapy (36 months). After 12 months, patients in the control group were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to Group 1 or 2. The observation of patients in these groups continued for 36 months.

Figure 1.

EXCEL (Long-term Effects of enhanced eXternal CountErpuLsation) study design.

Figure 1.

EXCEL (Long-term Effects of enhanced eXternal CountErpuLsation) study design.

HFrEF – heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HFmrEF – heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction, EECP – enhanced external counterpulsation, 35 – hours of EECP per one course

The effect of EECP treatment on the indicators of the structural and functional state of the vessels (

Table 1) was studied in addition to the assessment of the dynamics of exercise tolerance, myocardial stress markers (NT-proBNP) and LV systolic function (echocardiography). All investigations were conducted at baseline, after 12, 24 and 36 months of observation.

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed using a Phillips IU22 (Phillips, Netherlands) device according to a standard protocol, with assessment of the volumetric dimensions of the LV (end systolic volume, end diastolic volume), thickness of the interventricular septum and posterior wall of the LV, LV myocardial mass index (MMI), LV systolic (EF) and diastolic function (E/A) [

12].

Nailfold videocapillaroscopy was performed using Сapillaroscan-1 device (LLC New Energy Technologies, Russia). Resting capillary density (RCD) and its microcirculation functional reserves (capillary density in reactive hyperemia and venous occlusion tests) were estimated at a magnification of ×200, which reflects the endothelial function and the possibilities of capillary adaptation [

13].

Finger photoplethysmography was performed using Angioscan-01 (Angioscan-Electronics, Russia). Study protocol included analysis of the shape of the volumetric pulse wave, its intervals and amplitudes, the phases of heart activity, and allows for assessment of structural and functional parameters of both large arteries and the microcirculation [

14].

Applanation tonometry (A-pulse CASPro, HealthSTATS, USA) is a non-invasive research method that allows for the assessment of central aortic systolic pressure (CASP) and radial augmentation index (rAI), which indicates the degree of arterial stiffness [

15].

Exercise tolerance was measured using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), which is one of the validated and clinically informative methods of assessment of the physical activity of patients with CHF [

16].

In addition, adverse events associated with the progression of CAD (revascularization, acute coronary syndromes, myocardial infarction, deaths from all causes) were registered, which formed the vascular composite endpoint (VCE). Moreover, new onset episodes of atrial fibrillation or type 2 diabetes mellitus, decreased renal function, and decompensation of CHF with hospitalization were additionally assessed. Their combination formed the overall composite endpoint (OCE).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables with distribution different to normal were characterized by the median (Me) and interquartile range (Q25–Q75), otherwise – by the mean and standard deviation (M±SD). Categorical variables were described by presenting absolute values (n) and their relative values (%). Quantitative variables in two groups with non-normal distribution were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Comparison of dependent observations was performed using the Wilcoxon test, which provides a reliable assessment of changes in dynamics. was used in situations involving the analysis of three or more groups. Three or more groups with an abnormal distribution were compared quantitatively using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The event-free survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator. The obtained curves displayed the event-free survival functions in the studied groups and were used as a visual tool for analyzing prognostic differences between the observation groups. A stepwise approach with backward elimination of predictors using the Wald test was applied to construct logistic regression models. During the analysis, only statistically significant factors that passed the predetermined significance level were included in the model. ROC analysis was performed for quantitative variables that were considered significant during the analysis. The results were used to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) with a 95% confidence interval, and the corresponding curves were constructed to visualize the diagnostic value and threshold levels of the studied parameters. When comparing relative variables between groups, the odds ratio (OR) was used as a measure of effect, reflecting the probability of achieving the target outcome depending on the assigned therapeutic group. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM, USA) and StatTech v.3.0.5 (StatTech LLC, Russia).

3. Results

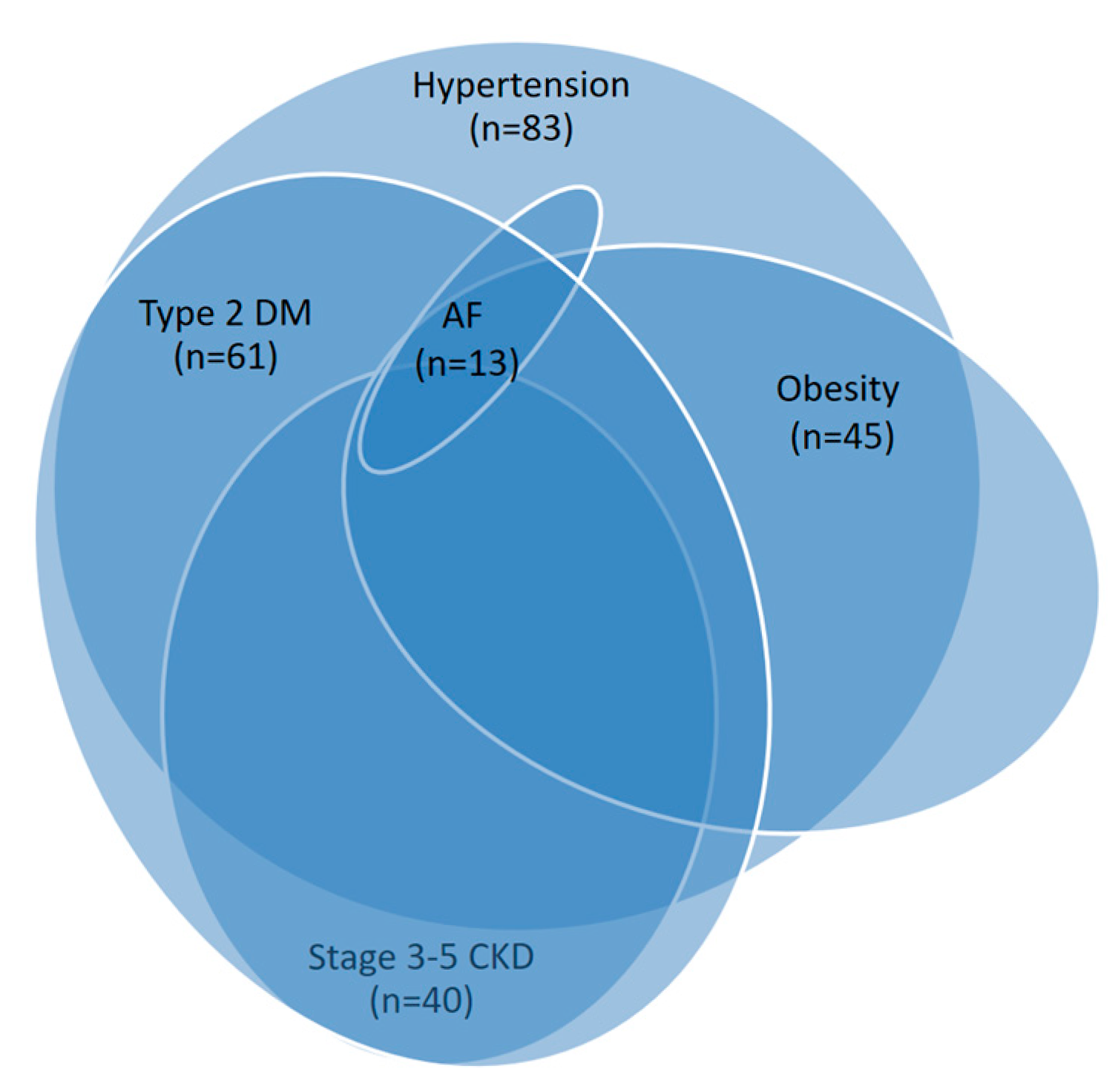

All patients with ischemic CHF had various comorbid conditions, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obesity, stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease, and atrial fibrillation (

Figure 2). The basic clinical and demographic characteristics of the study groups are summarized in

Table 2.

In all groups, a significant increase in exercise tolerance was identified during the observation period compared to the baseline (

Table 3). In Groups 1 and 2, the 6MWT distance after just 3 months increased significantly more than in Group 0. The maximum increase in physical tolerance was found in Group 2 and was maintained throughout the study (36 months).

Assessment of the dynamics of the NT-proBNP level showed a significant decrease in all groups. In EECP patient groups (1 and 2), NT-proBNP levels were significantly lower compared to the placebo counterpulsation group (

Table 4). In Group 2 (70 hours of EECP per year), the NT-proBNP level was significantly lower throughout the study than in Group 1 (35 hours of EECP per year). In addition, patients in Group 2 showed a significant increase in glomerular filtration rate levels over the observation period (36 months) compared to Group 1, which showed a decrease.

Improvement in exercise tolerance in patients was accompanied by a significant increase in LV systolic function. At the same time, patients in Group 2 (70 hours of EECP per year) had a significantly higher increase in LV EF compared to other groups (

Table 5) and these advantages were maintained throughout the observation period (36 months). A significant decrease in LV MMI compared to baseline values was found in each group, although the difference between groups was insignificant throughout the study.

In all groups, significant dynamics of the studied parameters (stiffness index [SI], reflection index [RI], phase shift [PS], occlusion index [OI]) of finger photoplethysmography were revealed compared to the baseline levels, except for SI in Group 0. A significant increase in IO values was also found after 12 months in Group 0. From the first year of observation, significant differences in the parameters of the functional state of the vessels (PS, IO) were recorded between the groups, while significant differences in the indicators of the structural state (SI, RI), more noticeable in Group 2, were revealed only in the 3rd year of observation (

Table 6).

Assessment of the capillaroscopy parameters (

Table 7) in Group 0 showed significant dynamics compared to the initial level only for the percentage of perfused capillaries (PPC). Differences between groups in the parameters of the functional state of microcirculation (PPC, capillary recovery percentage [CRP]) were observed already from the first year (the maximum increase was in Group 2) and persisted throughout the entire observation period (36 months). For the RCD, no significant intergroup differences were noted after 24-36 months of observation, although they were observed after 12 months.

The parameters of applanation tonometry (CASP, rAI), which characterize the structural remodeling of blood vessels, showed significant dynamics within the groups compared to the initial values (except for rAI in Group 0;

Table 8), but did not demonstrate significant differences between the groups over the study period.

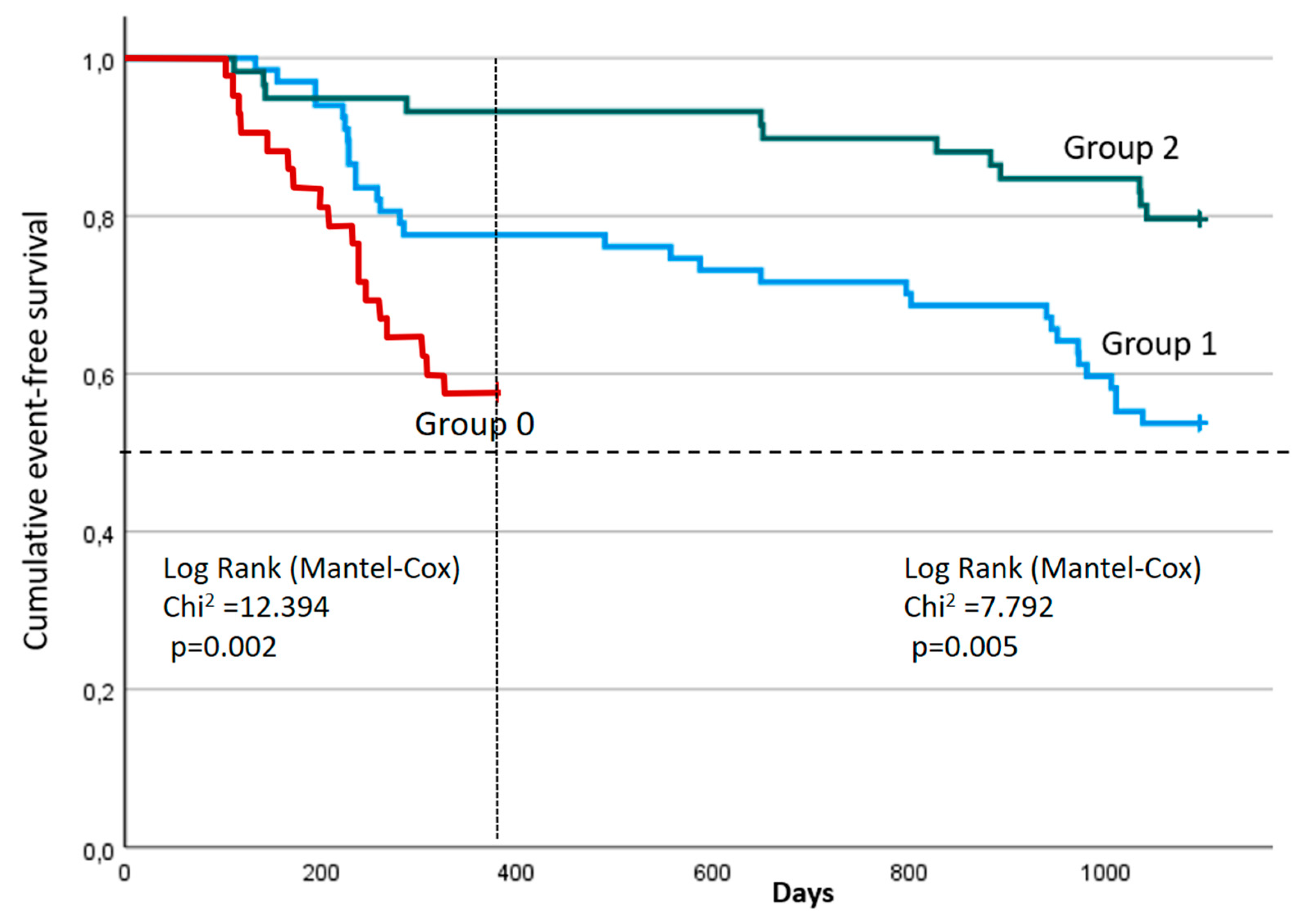

Analysis of the frequency of registered endpoints during the first 12 months of observation did not reveal significant differences for each of them separately (except for hospitalizations for CHF). The frequency of development of VCE and OCE was significantly lower in Group 2 compared with Groups 1 and 0 (

Table 9), while in placebo counterpulsation VCE and OCE were registered significantly more often than in the EECP groups. After 36 months, the difference between Groups 1 and 2 in the frequency of VCE and OCE events became even more notable.

A comparative analysis of event-free survival between the study groups using the Log-rank Mantel-Cox test demonstrated statistically significant differences both at 12 months (χ² = 12.394; p = 0.002) and at 36 months (χ² = 7.792; p = 0.005) (

Figure 3). The median survival times in Groups 0, 1 and 2 were not reached at either 12 or 36 months. At 12 months, the 75th percentile of survival time in Group 0 was 229 days from the start of observation (95% CI: 140 – ∞ day), the 75th percentiles of survival time in Groups 1 and 2 were not reached. After 36 months, the 75th percentile of survival in Group 1 was 284 days from the beginning of observation (95% CI: 228 –971 days), while Group 2 was not reached, which further indicates positive dynamics in this study population. The shape of the curves indicates better long-term clinical dynamics in Group 2 compared to others.

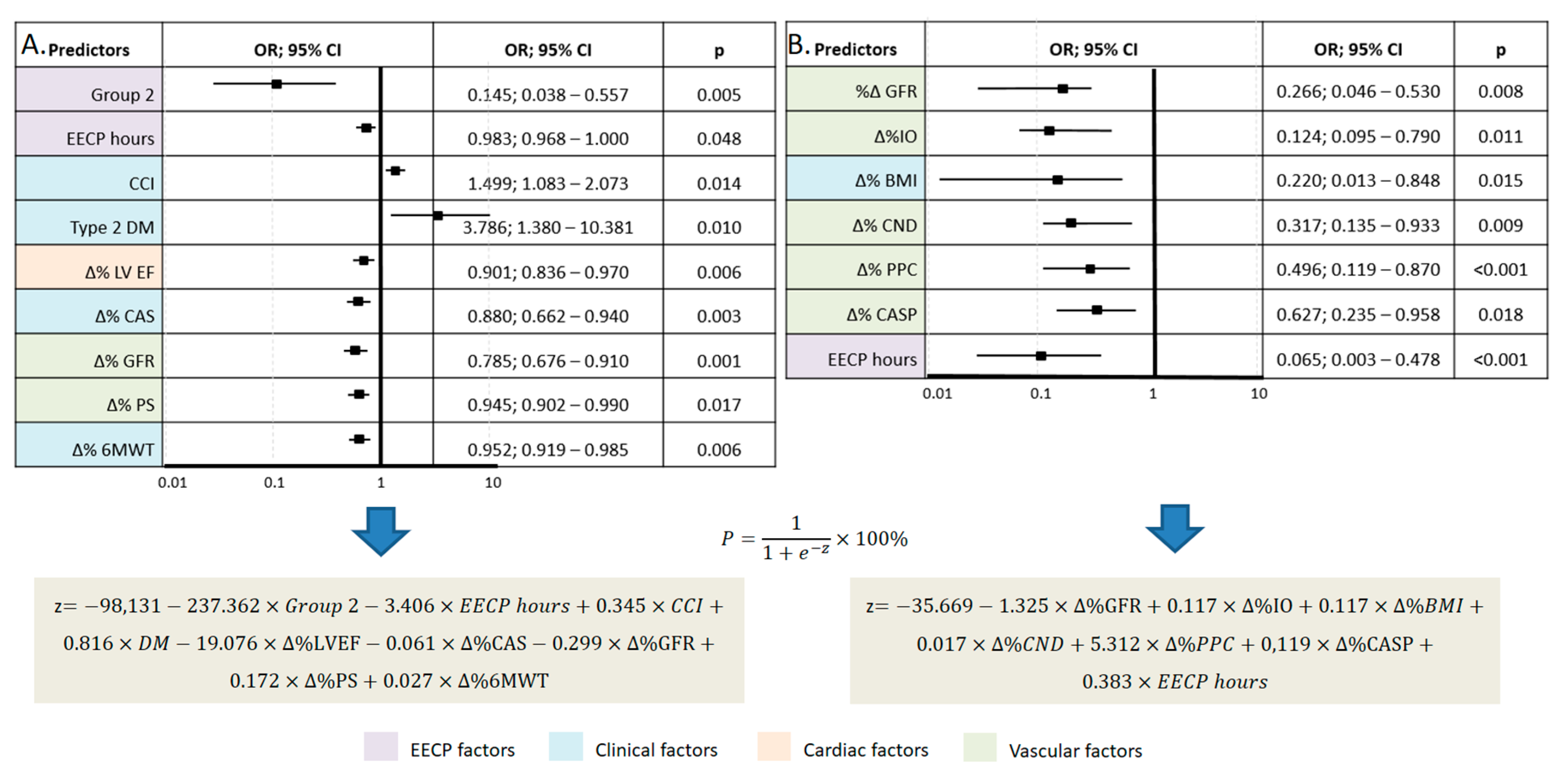

Predictive models were developed to determine the probability of OCE depending on significant factors (predictors) after 12 and 36 months of observation using the binary logistic regression method (

Figure 4). The number of observations was 119. The observed dependencies are described by the equation presented in

Figure 4. The resulting regression model is statistically significant (p = 0.001) in terms of the correspondence of predicted values to observed values when including predictors compared to the model without predictors. Nigelkirk's pseudo-R² was 32.7% and 74.6% for 12 and 36 months, respectively.

EECP – enhanced external counterpulsation, CCI – Charlson Comorbidity Index, DM – diabetes mellitus, LV EF – left ventricular ejection fraction, CAS – Clinical Assessment Scale, GFR – glomerular filtration rate, PS – phase shift, 6MWT – 6-minute walk test, OI – occlusion index, BMI – body mass index, CND – capillary network density, PPC – percentage of perfused capillaries, CASP – central aortic systolic pressure, P – assessment of the probability of overall composite endpoint, z –logistic function value.

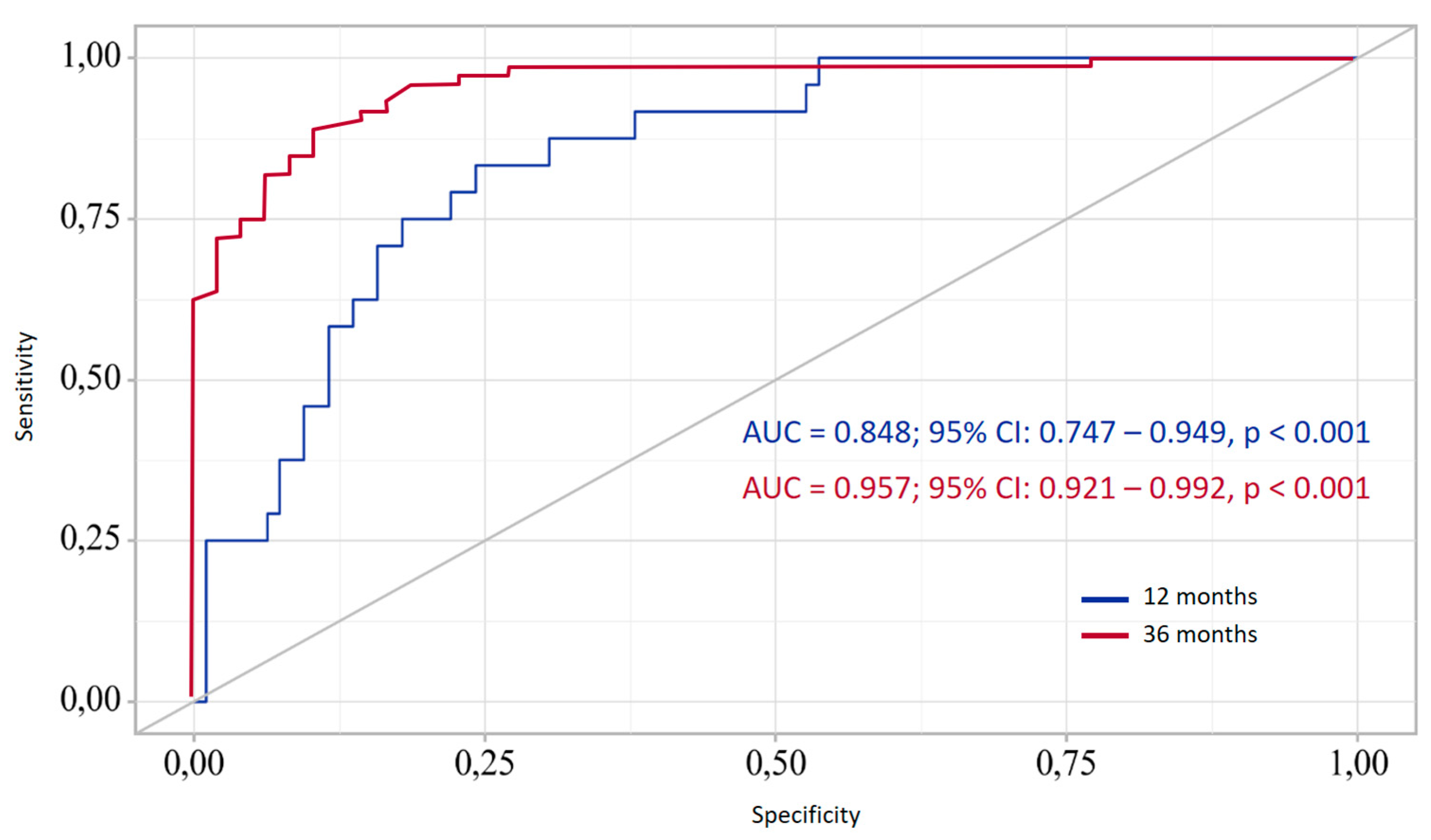

To assess the predictive ability of the developed model in relation of the ability of the achievement of target outcome, ROC curve characteristics analysis was used (

Figure 5).

The definition of P probability is a statistically significant predictor of OCE both after 12 and 36 months. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) indicated the ability of the model to distinguish between cases where the target condition was achieved. The slope of the ROC curve deviates significantly from the line of equal probability, confirming the presence of diagnostic value of the prognostic model. The optimal threshold probability value was determined based on the maximum value of the Youden index. As a result, the optimal threshold value (for 12 months) was recognized as the level of 0.227, corresponding to a sensitivity of 79.2% and a specificity of 77.9%. At the same time, the positive predictive value (PPV) was 78.2%, the negative predictive value (NPV) − 78.9%, which reflects the balanced quality of the classification. For 36 months, the optimal cutoff value was 0.626, which achieved a sensitivity of 88.7% and a specificity of 89.6%.

4. Discussion

Microcirculation plays a significant role in maintaining adequate tissue perfusion, which is necessary for tissue metabolic activity, especially in patients with CHF [

3]. Structural and functional vascular abnormalities are closely interrelated and contribute significantly to the pathophysiology of CHF. Thus, capillary density reduction and endothelial dysfunction can lead to a limitation of the coronary blood flow reserve, which is associated with worse clinical outcomes. Microvascular dysfunction is common in CAD, not limited to the coronary bed but extending to all vessels [

17].

Pathophysiological changes, including inflammation and oxidative stress, aggravate microcirculatory dysfunction in patients with CHF, impairing the response to shear stress and the involvment of non-perfused capillaries, which further reduce oxygen delivery to tissues [

18].

Vascular function of patients with CHF is significantly affected by concomitant diseases, systemic inflammation, and insulin resistance. The combination of impaired glucose metabolism and microvascular ischemia aggravates oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the myocardium, which requires additional mechanisms for their correction to improve the results of CHF treatment [

19].

The inability of microcirculation to adapt to increased metabolic demands often leads to exercise intolerance and poor functional capacity in patients with CHF, and also contributes to shortness of breath and fatigue, which significantly affects the quality of life of patients. Remawi B.N. et al. in their study indicate the need for complex approaches to resolve the problem of microcirculatory dysfunction in patients with CHF, and at the same time, reduce the overall burden of heart failure [

20].

EECP is one of the additional treatment methods for patients with CHF, complementing pharmacological and invasive approaches. The principle of action of EECP is similar to the "external heart". This technique of enhancing blood circulation using external inflatable cuffs placed on the lower extremities is a subject of interest due to its potential to improve tissue perfusion, including myocardial perfusion. In this work, all patients with ischemic CHF had various disorders of the state of large vessels (increased stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, increased CASP), as well as the microcirculatory bed (capillary density reduction, capillary architecture impairment, increased peripheral resistance, capillary endothelial dysfunction).

Long-term treatment of patients with ischemic CHF with the addition of EECP compared to the placebo counterpulsation group was accompanied by a significantly greater increase in exercise tolerance, improvement in LV systolic function (increase in LV EF), reduction in myocardial stress (decrease in NT-proBNP levels), as well as both functional (PS, IO, CRP, PPC) and structural (SI, RI, RCD, rAI, CASP) vascular parameters. Moreover, the effect size depended on the number of EECP courses per year (annual number of hours). Significant stable dynamics of vascular function parameters (PS, IO, CRP, PPC) was noted already in the first year of observation, and structural parameters (SI, RI, RCD) – from the second or third year.

In the EECP groups, compared with the placebo counterpulsation group, hospitalizations for CHF and composite endpoints (vascular and overall) were significantly less frequent after 12 months. At the same time, the lowest frequency of these events throughout the study was observed in the group with two EECP courses per year, in which, respectively, event-free survival was maximal.

Significant predictors of failure to achieve the overall CE after 12 months of observation were the dynamics of clinical factors (Charlson Comorbidity Index, presence of type 2 diabetes, clinical status, exercise tolerance), cardiac (LVEF), vascular (glomerular filtration rate, PS) factors, as well as factors associated with EECP treatment (annual number of EECP hours). Among the factors reducing the risk of adverse events after 36 months, changes in vascular factors (glomerular filtration rate, IO, CASP, capillary network density, percentage of perfused capillaries) predominated, with a decrease in the role of clinical and cardiac factors. It can be assumed that long-term compensation of insufficient tissue perfusion using EECP in patients with CHF contributes to the improvement of tissue metabolic activity and activation of angiotensin systems in tissues, including the myocardium. Therefore, EECP treatment may have significant potential in preventing adverse cardiovascular events and in increasing the quality and duration of life of these patients.

The cardiac-synchronized inflation and deflation of the leg cuffs during EECP promotes diastolic retrograde blood flow, causing an increase in diastolic perfusion pressure and increasing endothelial shear stress. This effect, by stimulating nitric oxide synthesis, promotes vasodilation [

21], collateral blood flow [

22], and thereby increases microvascular perfusion not only in ischemic but in all tissues.

Caceres et al. demonstrated that increasing microvascular perfusion during EECP treatment in patients with angina resulted in a significant reduction in angina episodes and improved exercise capacity [

23]. Moreover, EECP was associated with beneficial effects in patients with diabetic coronary microcirculatory dysfunction [

24].

In patients with CAD, the development of CHF leads to greater impairment of tissue perfusion due to a decrease in the LV systolic function and further activation of tissue angiotensin systems. By increasing diastolic perfusion pressure and coronary blood flow, EECP improves myocardial perfusion, myocardial oxygen delivery, and, as a result, improves exercise tolerance in patients with ischemic CHF [

25].

According to S. Lin et al., patients with CHF show significant improvements in cardiac output and stroke volume after EECP, indicating improved cardiac function [

26]. In the study by K.M. Tescon et al., 6.1% of patients had rehospitalizations within 90 days after EECP treatment versus the predicted 34.0% [

27]. Soran et al. revealed that in patients with refractory angina and LV dysfunction (LV EF<30 ± 8%), a course of EECP treatment resulted in a reduction in emergency department visits (by 78%) and hospitalizations (by 73%) [

28].

EECP stimulates physiological adaptive mechanisms such as revascularization (due to the development of collaterals), improvement of endothelial function, reduction of afterload, increase in diastolic filling of the LV, as well as reduction of the defect of mechano-energetic coupling of the myocardium [

29,

30], which is an advantage of this method.

Most studies of EECP in patients with ischemic CHF evaluate the effects of only a single course of EECP. Among other limitations the most significant are small sample sizes, lack of randomization and short follow-up periods. These factors significantly reduce the evidence for the effectiveness of EECP, but conducting larger and/or longer studies currently presents methodological challenges.

Limitations of our study include its single-center nature, relatively small sample size, and lack of use of “gold standards” in assessment of functional parameters. In addition, over a long follow-up period, there were difficulties in evaluation of the optimal pharmacotherapy, which changed with the advent of subsequent clinical guidelines.

5. Conclusions

Inclusion of EECP into standard treatment protocols for patients with CHF may provide additional options to relieve symptoms, improve function, reduce the risk of adverse events and prolong survival in patients with ischemic CHF. EECP should be considered as part of a comprehensive treatment strategy for patients with refractory angina and CHF not suitable for surgical intervention who have not responded adequately to drug therapy.

Increasing patient and physician awareness of EECP may have a significant impact on treatment strategy decisions and improve patient outcomes. Moreover, EECP may be a promising component of a patient-centered care that also includes lifestyle modification, improved treatment adherence, and, ultimately, improved overall treatment efficacy in patients with ischemic CHF.

Ongoing studies and additional long-term clinical trials will be needed to further elucidate the mechanisms of action and explore the benefits of EECP use in different groups of patients with CHF. Current research data suggest that EECP is a safe, effective, and beneficial treatment option for patients with ischemic CHF and refractory angina, but further research is needed to develop optimal EECP treatment protocols [

31] and expand the indications for its application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.L., Y.N.B.; methodology, A.S.L., Y.N.B.; software, A.S.L., O.A.S.; validation, A.S.L., O.A.S., formal analysis, A.S.L., O.A.S.; investigation, A.S.L., O.A.S. and N.A.N.; resources, A.S.L.; data curation, A.S.L., O.A.S. writing—original draft preparation, A.S.L., O.A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S.L., O.A.S., N.A.A., Y.N.B.; visualization, A.S.L., O.A.S.; supervision, A.S.L., Y.N.B.; project administration, A.S.L., Y.N.B.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Sechenov University (2020/34-20).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. We confirm that neither the manuscript nor any parts of its content are currently under consideration for publication with or published in another journal. All authors have approved the manuscript and agree with its submission to JCDD.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EECP |

enhanced external counterpulsation |

| CHF |

chronic heart failure |

| CAD |

coronary artery disease |

| LV |

left ventricle |

| EXCEL |

Long-term Effects of enhanced eXternal CountErpuLsation |

| EF |

ejection fraction |

| OMT |

optimal medical therapy |

| HFrEF |

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| HFmrEF |

heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction |

| MMI |

myocardial mass index |

| PS |

phase shift |

| SI |

stiffness index |

| CASP |

central aortic systolic pressure |

| rAI |

radial augmentation index |

| IO |

occlusion index |

| PPC |

percentage of perfused capillaries |

| CRP |

capillary recovery percentage |

| RI |

reflection index |

| RCD |

resting capillary density |

| VCE |

vascular composite endpoint |

| OCE |

overall composite endpoint |

| CABG |

coronary artery bypass grafting |

| CKD |

chronic kidney disease |

| NYHA |

New York Heart Association |

| 6MWT |

6-minute walk test |

| GFR |

glomerular filtration rate |

| AF |

atrial fibrillation |

| DM |

diabetes mellitus |

| PCI |

percutaneous coronary intervention |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| OR |

odds ratio |

| AUC |

area under curve |

| GFR |

glomerular filtration rate |

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

References

- Savarese, G. , Becher, P.M., Lund, L.H., Seferovic, P., Rosano, G.M.C., Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2020 Clinical practice guidelines for Chronic heart failure. Russian Journal of Cardiology 2020, 25, 4083. [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J. , Adamopoulos, S., Anker, S.D., Auricchio, A., Böhm, M., Dickstein, K., Falk, V., Filippatos, G., Fonseca, C., Gomez-Sanchez, M.A., et al.; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1787–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A. , Metra, M., Adamo, M., Gardner, R.S., Baumbach, A., Böhm, M., Burri, H., Butler, J., Čelutkienė, J., Chioncel, O., et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. , Hao, X., Xiao, S., Xun, L. The Effect of YiQiFuMai on Ischemic Heart Failure by Improve Myocardial Microcirculation and Increase eNOS and VEGF Expression. International Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020, 11, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. , Corban, M.T., Toya, T., Verbrugge, F.H., Sara, J.D., Lerman, L.O., Borlaug, B.A., Lerman, A. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is associated with exertional haemodynamic abnormalities in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzman, D.W. , Nicklas, B., Kraus, W.E., Lyles, M.F., Eggebeen, J., Morgan, T.M., Haykowsky, M. Skeletal muscle abnormalities and exercise intolerance in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ Physiol. 2014, 306, H1364–H1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamieva, Z.A. , Lishuta, A.S., Belenkov, Yu.N., Privalova, E.V., Yusupova, A.O., Rykova, S.M. Possibilities of enhanced external counterpulsation using in clinical practice. Rational Pharmacotherapy in Cardiology. 2017, 13, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E. , Desta, L., Broström, A. , Mårtensson, J. Effectiveness of Enhanced External Counterpulsation Treatment on Symptom Burden, Medication Profile, Physical Capacity, Cardiac Anxiety, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Refractory Angina Pectoris. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 35, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, R. , Khan, A., Zahid, S., Sami, A., Owais, S.M., Khan, F., Asjad, S.J., Jan, M.H., Awan, Z.A. The Effect of Enhanced External Counterpulsation (EECP) on Quality of life in Patient with Coronary Artery Disease not Amenable to PCI or CABG. Cureus. 2020, 12, e7987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenkov, Yu.N. , Lishuta, A.S., Slepova, O.A., Nikolaeva, N.S., Khabarova, N.V., Dadashova, G.M., Privalova, E.V. The EXCEL Study: Long-term Observation of the Effectiveness of Drug and Non-drug Rehabilitation in Patients with Ischemic Heart Failure. Kardiologiia. 2024, 64, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, C. , Rahko, P.S., Blauwet, L.A., Canaday, B., Finstuen, J.A., Foster, M.C., Horton, K., Ogunyankin, K.O., Palma, R.A., Velazquez, E.J. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2019, 32, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.T. , Liu, I.F., Tzeng, Y.H., Wang, L. Modified photoplethysmography signal processing and analysis procedure for obtaining reliable stiffness index reflecting arteriosclerosis severity. Physiol. Meas. 2022, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenkov, Iu.N. , Privalova, E.V., Danilogorskaia, Iu.A., Shchendrygina, A.A. Structural and functional changes in capillary microcirculation in patients with cardiovascular diseases (arterial hypertension, coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure) observed during computer videocapillaroscopy. Russian Journal of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery 2012, 5, 49–56, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Borg, A.L. , Trapani, J. The accuracy of radial artery applanation tonometry and intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring in critically ill patients: An evidence-based review. Nurs. Crit. Care. 2024, 29, 1751–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubnova, M.G. , Persiyanova-Dubrova, A.L. Six-minute walk test in cardiac rehabilitation. Cardiovascular Therapy and Prevention 2020, 19, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taqueti, V.R. , Di Carli, M.F. Coronary Microvascular Disease Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Options: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2625–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, M.P. , Merz, T. M., Hefti, U., Ince, C., Maggiorini, M., Pichler Hefti, J. Recruitment of non-perfused sublingual capillaries increases microcirculatory oxygen extraction capacity throughout ascent to 7126 m. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 2623–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.Y. , Doman, E.R., Sanchez, K., Chilton, R.J. Impact of insulin resistance and microvascular ischemia on myocardial energy metabolism and cardiovascular function: pathophysiology and therapeutic approaches. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 14, e00332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remawi, B.N. , Preston, N., Gadoud, A. Development of a complex palliative care intervention for patients with heart failure and their family carers: a theory of change approach. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, 24, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. , Chen, X., Cui, M., Ren, C., Yu, H., Gao, W., Li, D., Zhao, W. The improvement of the shear stress and oscillatory shear index of coronary arteries during Enhanced External Counterpulsation in patients with coronary heart disease. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0230144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y. , Xiong, L., Stinear, C.M., Leung, H., Leung, T.W., Wong, K.S.L. External counterpulsation enhances neuroplasticity to promote stroke recovery. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 361–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceres, J. , Atal, P., Arora, R., Yee, D. Enhanced external counterpulsation: A unique treatment for the "No-Option" refractory angina patient. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2021, 46, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J. , Wei, W., Shi, J., Huang, H., Wu, J., Wu, G. Abstract 13341: Enhanced External Counterpulsation Attenuates Coronary Microcirculation Dysfunction in Coronary Artery Disease With Diabetes: Primary Results of EECP-CMD Study. Circulation 2021, 144 (Suppl. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.F. , Wang, D., Li, X.M., Zhang, C.L., Wu, C.Y., Muppidi, V. Effects of enhanced external counterpulsation on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e26536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. , Xiao-Ming, W., Gui-Fu, W. Expert consensus on the clinical application of enhanced external counterpulsation in elderly people (2019). Aging Med. (Milton) 2020, 3, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tecson, K.M. , Silver, M.A., Brune, S.D., Cauthen, C., Kwan, M.D., Schussler, J.M., Vasudevan, A., Watts, J.A., McCullough P.A. Impact of Enhanced External Counterpulsation on Heart Failure Rehospitalization in Patients With Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 117, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U. , Ramsey, H.K., Tak, T. The role of enhanced external counter pulsation therapy in clinical practice. Clin. Med. Res. 2013, 11, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maack, C. Mechanoenergetische Defekte bei Herzinsuffizienz [Mechano-energetic defects in heart failure]. Herz. 2023, 48, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.F. , Li, Y.J., Cao, S., Xue, C.D., Tian, S., Wu, G.F., Chen, X.M., Chen, D., Qin, K.R. Hemodynamics of ventricular-arterial coupling under enhanced external counterpulsation: An optimized dual-source lumped parameter model. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed 2024, 250, 108191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishuta, A.S. , Slepova, O.A., Nikolaeva, N.A., Khabarova, N.V., Privalova, E.V., Belenkov, Yu.N. Effectiveness of different treatment regimens of enhanced external counterpulsation in patients with stable coronary artery disease complicated by heart failure. Rational Pharmacotherapy in Cardiology 2024, 20, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).