1. Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) refers to a heterogeneous group of clinically aggressive hematologic neoplasms defined by arrested myeloid maturation, resulting in the accumulation of myeloid blasts in bone marrow, blood, and other tissues [

1]. Cytogenetic and molecular characteristics further stratify AML into favorable, intermediate, and high-risk classifications. The high-risk category is defined by any of the following cytogenetic changes: DEK-NUP214, KMT2A-rearrangement, BCR-ABL1, GATA2, MECOM, deletion 5q, abnormal 17p, complex or monosomal karyotype, wild type NPM1 and FLT3-ITD, or mutated: RUNX1, ASXL1, or TP53 [

1].

In fit and eligible patients, the goal of treatment is to induce complete remission (CR) or partial remission (PR) by means of high intensity induction therapy usually involving seven days of continuous cytarabine infusion along with anthracycline treatment on days one through three (7+3). To assess the response to induction and determine the remission status, bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are done 7-10 days after completion of induction therapy and again after the recovery of platelets and neutrophil counts. Next, consolidation therapy is used after achievement of CR to further reduce the risk of disease recurrence by eradicating any residual leukemic cells that remained after induction, thereby preventing disease progression and improving overall survival. Consolidation therapy will involve either high intensity chemotherapy based around continuous infusions of high dose cytarabine (HiDAC) or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Finally, a subset of AML patients including those who were ineligible for transplant, those with FLT3-mutations, or those with minimal residual disease (MRD) positive AML will benefit from non-myelosuppressive maintenance therapy over months to year. Standard induction therapy utilizing the 7+3 regiment results in 5-year overall survival (OS) rates of 30-45%. In patients with high-risk status, HSCT remains the only curative therapy currently available with reported overall survival rates ranging from 30-70% when accounting for factors including type of transplant, source of stem cells, the conditioning regiment used, and the stage of the disease. Despite the relative success of HSCT in high-risk AML patients, the literature reports relapse rates ranging from 30-50% [

2].

The logistics involved with transplant, including patient HLA typing, donor selection, pre-transplant conditioning, and stem cell collection, might necessitate consolidation chemotherapy. Over the past several decades, there have been several studies that compare the outcomes in AML patients treated with HiDAC versus intermediate dose cytarabine (IDAC). Regarding overall survival (OS), relapse-free survival (RFS), disease-free survival (DFS), and all-cause mortality, IDAC appears to be equivalent to HiDAC in patients with high-risk AML. IDAC also has a more favorable toxicity profile than HiDAC [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Other studies have demonstrated that patients treated with IDAC will have a higher likelihood of successfully receiving HSCT than those who are treated with HiDAC consolidation therapy [

8]. We looked at the outcomes for high-risk AML patients evaluated and treated at our transplant institution, the Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University, from 2003 to 2020; for those not transplanted, we considered whether the use of consolidation therapy with HiDAC was a contributing factor to lack of HSCT in this population.

2. Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis and evaluated patient characteristics and outcomes of high-risk AML patients treated at our transplant institution, the Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University, who were diagnosed and either did or did not receive HiDAC consolidation therapy between November 2003 and December 2020. High-risk AML was defined as those patients, whose AML was positive for one (or more) of the following genetic mutations: FLT3, monosomy 5,7 and/or complex cytogenetics (CG) defined as having greater than or equal to 3 CG changes). For those not transplanted, we reviewed the clinical course following HiDAC consolidation therapy and identified the adverse effects, if any, that would preclude HSCT. We calculated descriptive statistics on age, gender, and race of the cohort. We stratified the cohort into subgroups based on induction status, HiDAC status, IDAC status, HSCT status, and reasons for not undergoing HSCT including death/infection versus other causes. Epi Info Software version 7.2.5.0 was utilized in the generation and interpretation of the descriptive statistics.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics Overall

Patient characteristics are described as seen in

Table 1. A total of 92 patients diagnosed with high-risk AML were evaluated at our center from November 2003 to December 2020. The entire cohort had a median age of 60, mean age of 55.3, with a range from 14-85. The racial breakdown of the cohort is as follows: White patients made up 69.6% (n=64), black patients made up 27.2% (n=25), Hispanic patients made up 1.1% (n=1), and other racial identities made up 2.1% (n=2). Males comprised 46.7% (n=43) and females comprised 53.3% (n=49).

3.2. Characteristics of Patients Who Received Induction Therapy Versus Those Who Did Not

Of the 92 patients in the total cohort, 81.5% (n=75) underwent induction therapy and 18.5% (n=17) did not due to prohibitive comorbidities, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, being lost to follow-up, or patient preference. For patients who did receive induction therapy, the median age was 55, mean age 50.8, with a range of 14-77. The racial breakdown included 69.3% whites (n=52), 26.7% black (n=20), 1.3% Hispanic (n=1), and 2.7% other (n=2). Males comprised 41.3% of this group (n=31) and females comprised 58.7% (n=44).

For patients who did not receive induction therapy, the median age was 77, mean age 75.4, with a range of 64-85. The racial breakdown included 70.5% whites (n=12), 29.5% black (n=5), and 0% Hispanic or other. Males comprised 70.5% (n=12) of the group in females comprised 29.5% (n=5).

As noted in

Table 2, when comparing the mean age for patients who received induction therapy, 50.8, to those who did not, 75.4, there is a statistically significant difference, P<0.0000. There is also a significant difference in the percentage of patients who did not get induction that are male, 70.5%, compared to the percentage of patients who did get induction that are male, 42.1%, P=0.0012.

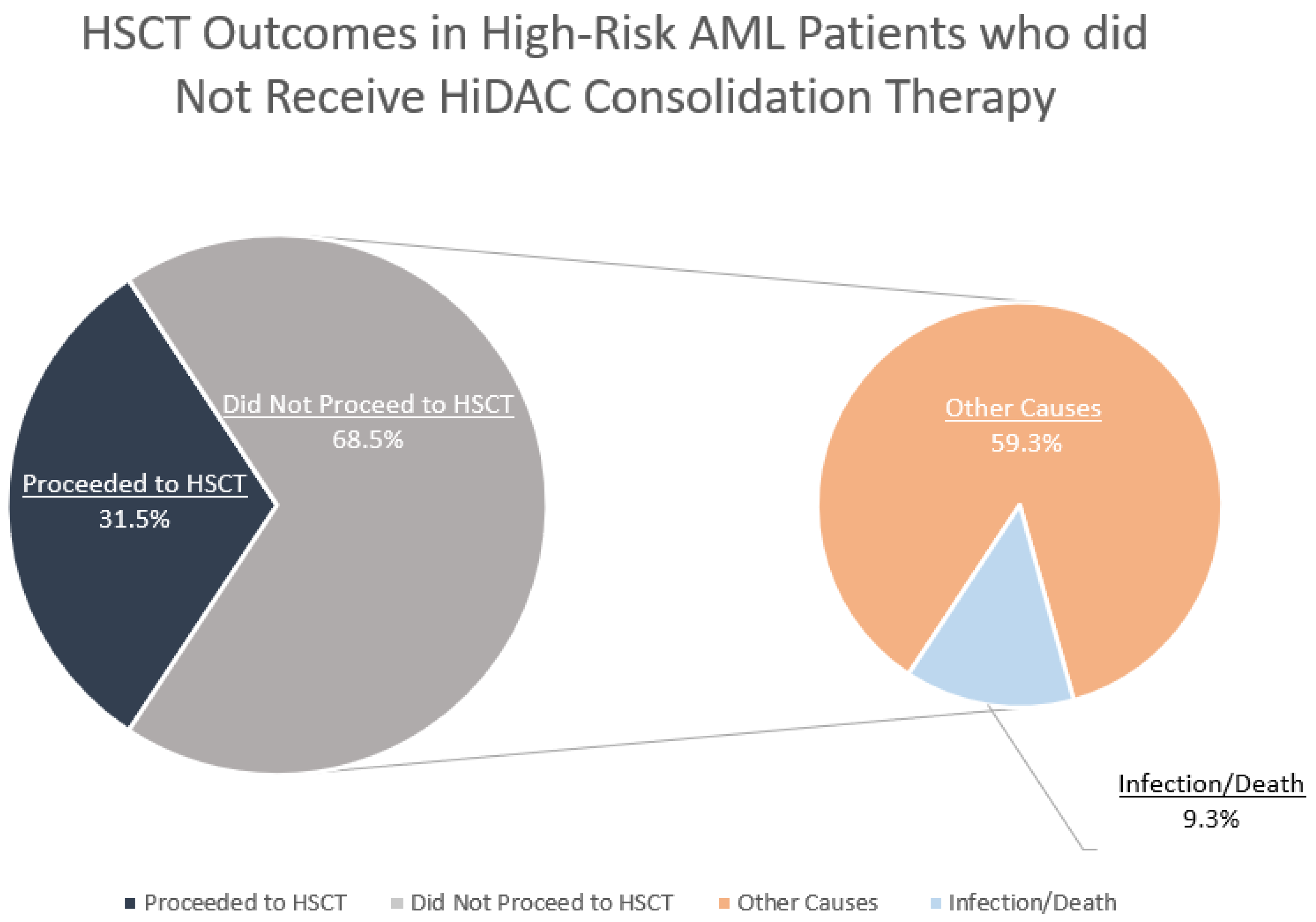

3.3. Characteristics of Patients Who Did Not Receive HiDAC Consolidation Therapy and Reasons for no HSCT

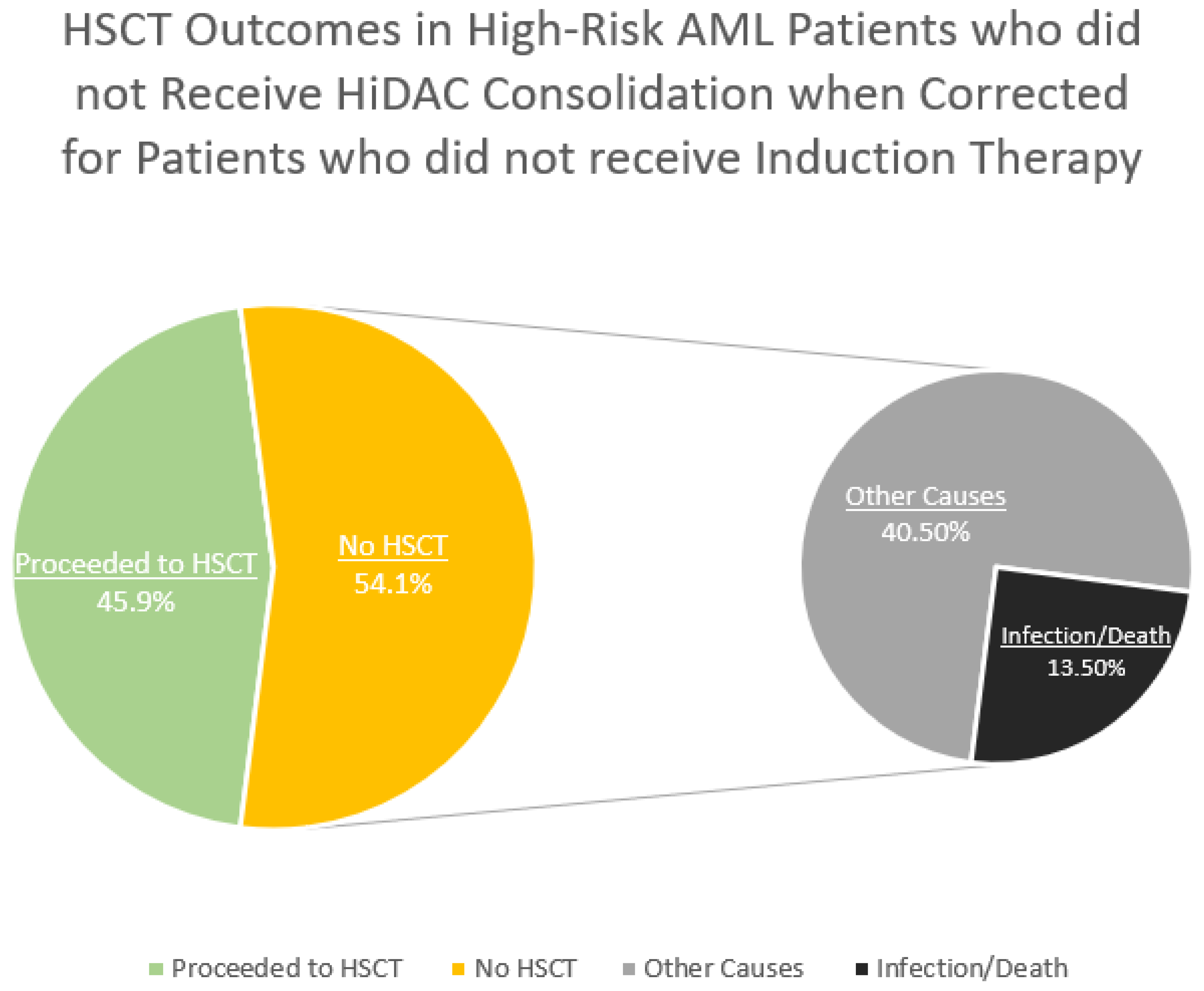

HiDAC consolidation therapy was not administered to 58.7% of patients (n=54). Of these 54 patients, 31.5% (n=17) were able to successfully undergo HSCT. The other 68.5% (n=37) of patients were unable to undergo HSCT. Reasons for these patients not successfully receiving HSCT included prohibitive comorbidities or ECOG performance status (n=17, 45.9%), failed induction or disease progression (n=12, 32.4%), infection or death (n=5, 13.5%), patients declining transplant (n=2, 5.4%), and being lost to follow-up (n=1, 2.7%).

3.4. Comparing Patients Who Did Not Receive HiDAC Consolidation Therapy Based on Their HSCT Status

The median age of patients who did not receive HiDAC consolidation therapy but were able to undergo HSCT was 42 compared to a median age of 68 in patients who did not receive HiDAC consolidation therapy and were not able to undergo HSCT. As described in

Table 3, when comparing the mean age for patients who did not receive HiDAC consolidation therapy or HSCT, 65.7, to that of patients who did not receive HiDAC consolidation therapy but did undergo HSCT, 44.3, there is a statistically significant difference, P=0.0002. The racial distribution (P=0.4082) and sex differences (P=0.1997) between these 2 groups were not statistically significant.

3.5. Characteristics of Patients Who Did Receive HiDAC Consolidation Therapy

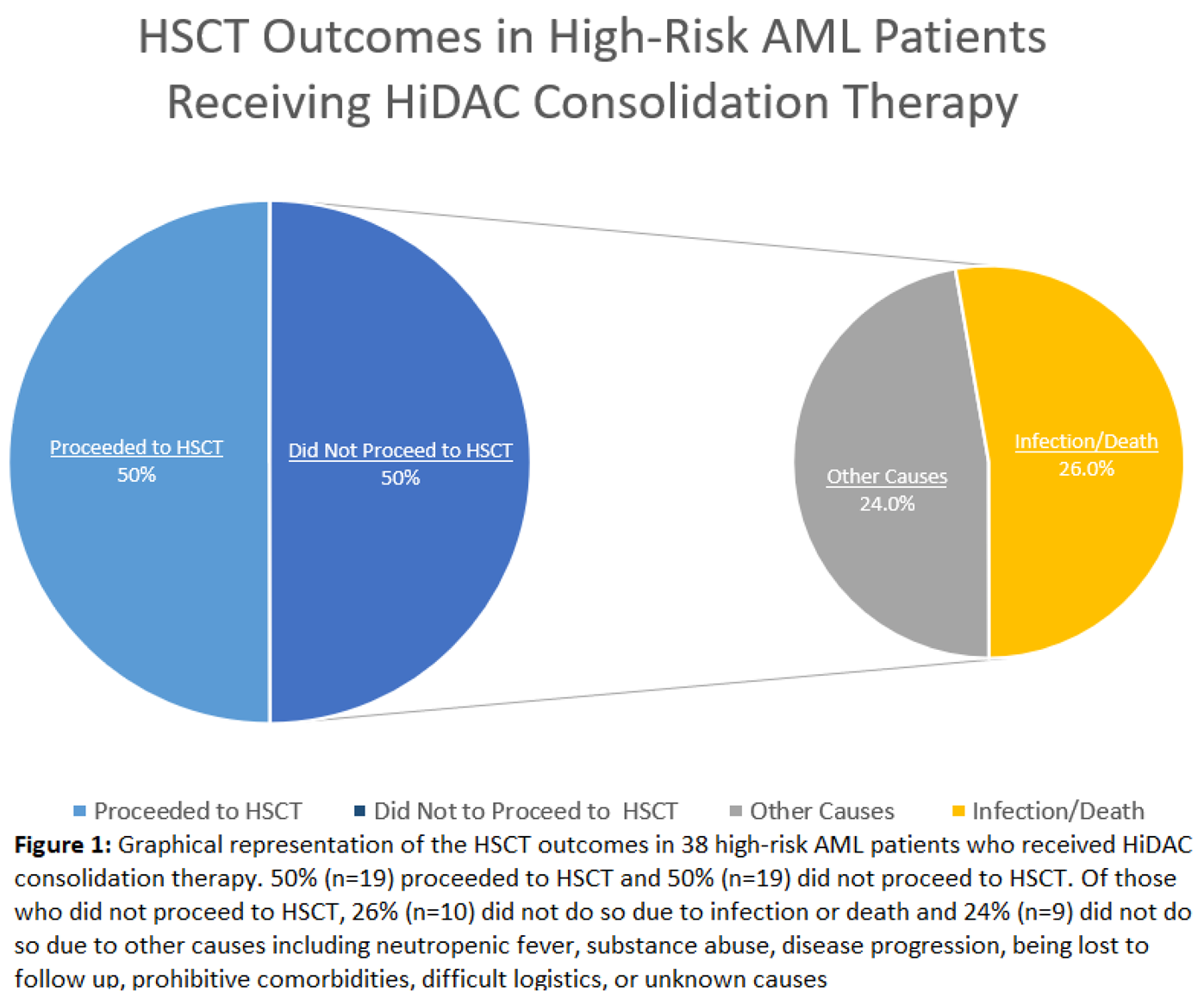

Patients who did receive HiDAC consolidation therapy comprised 41.3% of the total patient cohort (n=38). The median age in this group was 53, the mean age was 50.1, and the range was between 19 and 70. Racial breakdown of this group is as follows: White patients made up 68.4% (n=26), black patients made up 28.9% (n=11), and Hispanic patients made up 2.7% (n=1). Males comprised 36.8% (n=14) of this group and females comprised 63.2% (n=24). Of the patients who received HiDAC consolidation therapy, 50% (n=19) went on to HSCT and 50% (n=19) did not proceed to HSCT. For patients who did not receive HSCT, 73.6% (n=14), underwent HLA-typing, indicating consideration for transplantation.

As seen in

Table 4, there was no statistically significant difference in mean age (P=0.0603), racial distribution (P=0.4054), or sex (P=0.1414) when comparing those patients who received HiDAC to those who did not.

Patients who underwent HiDAC consolidation therapy and HSCT had a median age of 53, mean age of 47.0, and a range of 19-65. The racial breakdown of this group contains 73.7% white patients (n=14) and 26.3% black patients (n=5). Males comprised 31.6% of this group (n=6) while females comprise 68.4% (n=13).

3.6. Characteristics of Patients Who Received HiDAC Consolidation and Reasons for Not Undergoing HSCT

Of the 19 patients who received HiDAC consolidation therapy but were unable to undergo HSCT, 52.6% (n=10) did not proceed to transplant due to infectious complications or death and the remaining 47.3% (n=9) had noninfectious reasons for non-transplant.

For patients who did receive HiDAC consolidation therapy but were unable to proceed to HSCT due to infection or death, the median age was 57, mean age 54.6, with a range 29-70. The racial breakdown of this group is as follows: White patients made up to 60% (n=6), black patients made up 30% (n=3), and Hispanic patients made up 10% (n=1). Males comprised 20% (n=2) of this group in females comprised 80% (n=8).

For patients who did receive HiDAC consolidation therapy but were unable to proceed to HSCT due to noninfectious causes, the median age was 56, mean age 51.8, with a range of 24-63. White patients made up 66.7% (n=6) of this group while black patients made up 33.3% (n=3). Males comprised 66.7% (n=6) of this group while females comprised 33.3% (n=3).

Of the 10 patients without HSCT after HiDAC consolidation therapy due to infection, seven had an infection that prevented them from receiving a transplant and three patients died prior to transplant due to septic shock or multi-organ failure. Infections included bacteremia from Klebsiella, Escherichia Coli (E.Coli), Proteus, group B strep, vancomycin resistant Enterococcus Faecalis (VRE), and coagulase negative staph, pneumonia from Klebsiella, urinary tract infections (UTI) from extended spectrum beta-lactamase resistant E. Coli, Klebsiella, and proteus mirabilis, fungal sinusitis, and Clostridium difficile colitis. Other reasons that prevented HSCT included neutropenic fever with an unknown cause, prohibitive comorbidities, substance abuse, disease progression, and lack of follow-up, and unknown causes.

3.7. Characteristics of Patients Who Received IDAC Consolidation Therapy

Of the 5.4% (n=5) of patients who received IDAC consolidation therapy, 60% (n=3) were able to undergo HSCT while 40% (n=2) were not. The median age of patients able to undergo HSCT after IDAC consolidation therapy was 30 with a mean of 40 compared to a median of 65.5 and a mean of 65.5 and those who received IDAC consolidation therapy but were unable to undergo HSCT.

3.8. Comparing Time from Diagnosis to HSCT in Patients Who Did Versus Did Not Receive HiDAC Consolidation Therapy

As described in

Table 5, in the 19 patients who received HiDAC consolidation therapy, the time from diagnosis to HSCT in days was as follows: Range 97-1339, median 326.5, mean 442.3. For the 17 patients who did not receive HiDAC consolidation therapy, the time from diagnosis to HSCT and days was as follows: Range 46-511, median 127, mean 165.7. When comparing the mean time from diagnosis to HSCT in days for these 2 groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA), there initially appears to be a statistically significant difference, P value 0.00416. However, Barlett’s Test for Inequality of Population Variances yields a P value of 0.00002. Any P value less than 0.05 suggests that the variances are not homogenous between these two groups and that ANOVA is not appropriate. Mann-Whitney/Wilcoxon Two-Sample Test (Kruskai-Wallis test for two groups) has a non-significant P-value of 0.4020.

4. Discussion

Why we use HiDAC

The current paradigm of HiDAC use for post-remission/consolidation therapy in patients with AML is based on the landmark CALGB 8525 study from the late 1990’s which established HiDAC as the standard of care for AML post-remission therapy [

9]. As evidenced by that study, for patients aged 60 or younger there was a significant difference in the rate of continued complete remission (CR) after a 5-year progression free survival (PFS) for those patients receiving HiDAC (3000 mg/m2), Intermediate dose cytarabine (IDAC) (400 mg/m2), and Low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) (100 mg/m2) respectively (p=0.0007). It is important to note however, that for patients over the age of 60, the probability of continuous CR after 4 years was 14% or less in each of the three cytarabine groups.

HiDAC and the timing of HSCT Evaluation

In the decades since this landmark trial, numerous studies have demonstrated that the role of HiDAC consolidation therapy compared to HSCT alone or IDAC is equivocal at best and is more often associated with unnecessary risk which subsequently prevents a subset of patients from receiving HSCT. Our data suggests that for patients with high-risk AML as defined by the 2017 European Leukemia Net (ELN) risk stratification genotypes DEK-NUP214, KMT2A-rearrangement, BCR-ABL1, GATA2, MECOM, deletion 5q, abnormal 17p, complex or monosomal karyotype, wild type NPM1 and FLT3-ITD, or mutated: RUNX1, ASXL1, or TP53, the HSCT evaluation, the only curative option in this population, should start during the induction admission. The latter would negate the need to administer consolidation chemotherapy in an attempt to, “bridge the gap” between induction and transplant. Furthermore, if consolidation therapy is deemed necessary in this patient population, IDAC be used instead of HiDAC due to its equivalent benefit and lower rates of toxicity and infections which prevent HSCT.

HiDAC Versus IDAC: Risk Versus Benefit

Several studies investigating the differences between the risk profile of HiDAC and IDAC have confirmed the intuitive notion that increasing doses of a cytotoxic agent will have increasing levels of adverse effects. A 2015 retrospective cohort study from Shepshelovich and colleagues revealed that the pharmacodynamics of cytarabine induced leukopenia demonstrated a monophasic decline pattern in WBC and ANC with HiDAC exhibiting a steeper rate of decline compared to IDAC [

10]. Given the inferior toxicity profile, the justification for using HiDAC over IDAC comes from the idea that the benefits gained in DFS, PFS, and OS outweigh the toxicity incurred. These benefits, however, do not appear to be present in patients with high-risk cytogenetics. A 2017 meta-analysis by Wu and colleagues compared the benefit and safety of HiDAC (2-3 g/m

2 twice daily), IDAC (1–2 g/m

2 twice daily), and LDAC (<1 g/m

2 twice daily) within 10 randomized phase III trials with 4008 AML patients from 1994 to 2016 and found that although HiDAC did show a benefit compared to IDAC in disease free survival (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.33–0.57,

P<.00001), these benefits were biased by those with favorable cytogenetics [

10]. A 1996 study by Stasi and colleagues showed that HiDAC as part of post remission therapy resulted in a substantial improvement in the cure rate in patients less than 60 years old. However, the primary benefit was derived from those with low- or intermediate-risk karyotypes and the potential benefits of an intensification of chemotherapy in elderly AML patients were by far outweighed by unacceptable toxicity [

11]. When comparing clinical outcomes in AML patients receiving either HiDAC or IDAC for consolidation therapy, a consistent pattern is noted. Firstly, there does not appear to be any difference in RFS, DFS, OS, or all-cause mortality when using HiDAC. Secondly, HiDAC has higher levels of toxicity, adverse effects, and infection risk. A 2022 paper from the Thai AML registry noted that consolidation therapy in patients with intermediate to high-risk disease, who achieve their first CR should be treated with IDAC as compared to HiDAC as the former has fewer side effects [

4]. Another 2022 study from Ravikumar and colleagues found that IDAC had lesser toxicity when compared to HiDAC, but that determining if efficacy was comparable would need studies with longer follow up periods and prospective studies [

5]. In a 2021 paper from Tangchitpianvit and colleagues involving sixty-two AML patients, over 90% of which were either intermediate or high-risk, receiving either HiDAC or IDAC for consolidation therapy found that the one-year RFS in the IDAC group was 63.33% and 46.87% in the HiDAC group (

P = 0.137) and the 1-year OS was 93.33% and 84.37% in the IDAC and HiDAC, respectively (

P = 0.691), both of which were not statistically significant [

6]. A meta-analysis performed by Magina et al compared the efficacy of post-remission HiDAC to IDAC/Low-dose cytarabine (LDAC). This included 9 studies ranging over a period of nearly 25 years. The findings of which were similar to the previous studies mentioned. There was no significant difference between HiDAC regimens and IDAC/LDAC when it comes to RFS (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.8-1.01) or OS (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.87-1.09) [

7]. This evidence suggests that if consolidation therapy needs to be administered in this patient population, IDAC should be used instead of HiDAC as the goal in treating patients with high-risk AML is to give them a chance at cure with HSCT. HiDAC appears to decrease the chance of achieving HSCT due to the adverse effects secondary to immunosuppression and infection. The latter was demonstrated by Hanoun and colleagues in their 2022 paper involving 642 patients who received HiDAC and 178 patients who received IDAC consolidation and found that more patients treated with IDAC received allogenic hematopoietic cell transplantation in first remission compared to those treated with HiDAC (37.6 vs. 19.8%, p < 0.001) [

8]. Given that there were significant differences in important patient characteristics including cytogenetic risk group, propensity score weighting was used and found that there was no significant benefit of HiDAC compared to IDAC in consolidation for patients under 65, independent of ELN risk group.

HiDAC Versus HSCT Alone

There is evidence to suggest that HSCT is preferrable to consolidative chemotherapy in this patient population due to the chance for cure and the improvements in DFS, RFS, and OS. A 1995 study by Zittoun and colleagues found that four-year DFS indicated a substantial advantage of both allo and auto-BMT (55% and 48% respectively) over chemotherapy alone (30%) [

12]. Kaplan-Meier estimates from a 2016 study by Cornelissen and colleagues on patients with intermediate risk AML demonstrated that HSCT recipients had significantly better OS than patients receiving chemotherapeutic post remission therapy (P=0.001) [

13]. The question of the benefit or need for consolidation chemotherapy before proceeding to transplant after achieving first complete remission (CR1) has been a subject of debate. A 2018 meta-analysis by Zhu and colleagues involving 6 studies including 1659 patients revealed that no significant benefit was found for post-remission consolidation chemotherapy in patients who received allo-HSCT when it came to OS and relapse occurrence. The authors here suggest that patients should proceed to allo-HSCT as soon as CR1 is attained [

14].

Is HiDAC Consolidation preventing some high-risk AML patients from receiving HSCT?

Our data suggested that of the 38 high-risk AML patients who received HiDAC consolidation therapy, 19 of them were unable to proceed with HSCT indicating that HiDAC treatment was associated with a transplantation rate of 50%. Ten of those 19 patients did not proceed to HSCT due to infection or death. These are likely associated with the severe immunosuppression and toxicity from HiDAC. Five out of the 19 of those who were not transplanted did not have HLA-typing done at the time of first admission, preventing the possibility of early transplant following induction therapy.

Of the 54 high-risk AML patients who did not receive HiDAC consolidation therapy, 37 were unable to proceed with HiDAC treatment. On the surface, this appears to suggest that not pursuing HiDAC consolidation therapy was associated with a transplantation rate of 31.5%. However, when we removed those individuals who were either too sick to receive induction therapy or opted against induction therapy for other reasons, the transplantation rate increased to 45.9%. Importantly, the patients in this cohort who were unable to proceed to HSCT largely did so for reasons other than infection or death i.e. disease progression, failed induction, being lost to follow-up, or patient preference. The patients who did not receive HiDAC consolidation therapy but were able to proceed to HSCT were significantly younger, mean age 44.3, than those who did not receive HiDAC consolidation therapy or HSCT, mean age 65.7. When comparing this trend to those who did receive HiDAC consolidation therapy, a different relationship is noted. There was no significant difference in the mean age of those patients who received HiDAC and HSCT, 47, to those who received HiDAC and did not undergo HSCT due to infection/death, 54.6, or other causes, 51.8. This suggests the underlying factors preventing patients who receive HiDAC from undergoing HSCT are not related to patient’s other comorbidities, EGOG performance status, or age.

When comparing the time from diagnosis to HSCT in patients who received HiDAC consolidation therapy to those who did not, there was a non-significant increase in the number of days before HSCT in those who received HiDAC.

The data from our study and the literature on this topic over the past 30 years suggest starting the process of HSCT during the induction admission. HSCT is the sole curative option for high-risk AML patients, and the concept of bridging the period between induction and HSCT with HiDAC consolidation appears to offer no additional benefit compared to IDAC. Moreover, this approach prevents a subset of this population from being fit enough to receive HSCT. In cases where patients were able to undergo HSCT after getting HiDAC, they had to wait on average, longer than those who did not receive HiDAC. Of the 5 patients in our cohort that received IDAC consolidation therapy, 3 were able to receive HSCT and 2 were unable to due to reasons other than infection/death. If consolidation therapy is deemed necessary in this patient population, IDAC should be used instead of HiDAC due to its equivalent benefit and lower rates of side effects, toxicity, and infections which prevent HSCT.

Limitations

It is important to note that these results represent a retrospective analysis of high-risk AML patients at our transplant center and should be interpreted in the context of this study. This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, the study’s single-center, retrospective design may limit generalizability due to reflecting the protocols and patient characteristics unique to one institution. Second, the sample size of patients who received IDAC instead of HiDAC at our institution is exceedingly small and therefore limits any statistically significant analysis.

5. Conclusions

The data from our study and the literature on this topic over the past 30 years suggest starting the process of evaluating patients for HSCT during the induction admission. HSCT is the sole curative option for high-risk AML patients, and the concept of “bridging the period between” induction and HSCT with HiDAC consolidation appears to offer no additional benefit compared to IDAC. Moreover, this approach prevents a subset of this population from being fit enough to receive HSCT. These results represent a retrospective analysis of high-risk AML patients at the Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University, and prospective research should continue to be done to further elucidate these findings.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table 1 reports the demographics of the high-risk AML patients treated at the Georgia Cancer Center from 11/2003 to 12/2020. Supplementary tables 2-4 compare patient characteristics based on induction status, HSCT status, and HiDAC status. Supplementary table 5 compares time from diagnosis to HSCT based on HiDAC status. Supplementary tables 6-8 describe reasons for not undergoing HSCT following HiDAC, types of infections in patients following HiDAC, and IDAC outcomes. Supplementary figures 1-3 compare HSCT outcomes in patients based on HiDAC status both with and without correcting for induction status.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization M.S., V.K., and J.C.; Data curation: M.S., A.S., Y.R., I.P.; Formal Analysis: M.S., M.M.; Original Draft Preparation: M.S.; Review and Editing: A.S., Y.R., I.P., J.C., A.J., A.K., C.H., V.K.; Supervision: V.K.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for publication was waived given the retrospective nature of the study per the Institutional Review Board at Augusta University

Institutional Board Review Statement

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of Augusta University. The study was granted an exemption under Category 4, as it involved secondary analysis of de-identified data with no direct interaction with human subjects

Data Availability Statement

The author declares that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article

Conflicts of Interest

JC discloses relationships with Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharma, Syndax, Nerviano, Lilly as a consultant. He reports receiving research funding from Novartis, Sun Pharma, Ascentage, and AbbVie. He is also a current holder of stock options and has membership on the Board of Directors at Biopath Holdings. All other authors have no financial disclosure to report.

Abbreviations

AML; Acute Myeloid Leukemia, HiDAC; High-Dose Cytarabine, IDAC; Intermediate-Dose Cytarabine, HSCT; Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation, MRD; Minimal Residual Disease, OS; Overall Survival, RFS; Relapse-Free Survival, CG; Cytogenetics, ECOG; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, E.Coli; Escherichia Coli, VRE; Vancomycin Resistant Enterococcus Faecalis, ANOVA; Analysis of Variance, CR; Complete Remission, PFS; Progression-Free Survival, LDAC; Low-dose cytarabine, ELN; European Leukemia Net

References

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.; Thiele, J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Le Beau, M.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Cazzola, M.; Vardiman, J.W. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016, 127, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döhner, H.; Estey, E.; Grimwade, D.; Amadori, S.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Büchner, T.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Larson, R.A.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 2017, 129, 424–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepshelovich, D.; Edel, Y.; Goldvaser, H.; Dujovny, T.; Wolach, O.; Raanani, P. Pharmacodynamics of cytarabine induced leucopenia: a retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanswangphuwana, C.; Polprasert, C.; Owattanapanich, W.; Kungwankiattichai, S.; Rattarittamrong, E.; Rattanathammethee, T.; Limvorapitak, W.; Saengboon, S.; Niparuck, P.; Puavilai, T.; et al. Comparison of Three Doses of Cytarabine Consolidation for Intermediate- and Adverse-risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Real World Evidence From Thai Acute Myeloid Leukemia Registry. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022, 22, e915–e921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravikumar, D.; Saju, H.; Choudary, A.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Dubashi, B.; Ganesan, P.; Kayal, S. Outcomes of HIDAC 18 g Versus IDAC 9 g in Consolidation Therapy of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Retrospective Study. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2021, 38, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangchitpianvit, K.; Rattarittamrong, E.; Chai-Adisaksopha, C.; Piriyakhuntorn, P.; Rattanathammethee, T.; Hantrakool, S.; Tantiworawit, A.; Norasetthada, L. Efficacy and safety of consolidation therapy with intermediate and high dose cytarabine in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Hematology 2021, 26, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magina, K.N.; Pregartner, G.; Zebisch, A.; Wölfler, A.; Neumeister, P.; Greinix, H.T.; Berghold, A.; Sill, H. Cytarabine dose in the consolidation treatment of AML: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood 2017, 130, 946–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanoun, M.; Ruhnke, L.; Kramer, M.; Hanoun, C.; Schäfer-Eckart, K.; Steffen, B.; Sauer, T.; Krause, S.W.; Schliemann, C.; Mikesch, J.-H.; et al. Intensified cytarabine dose during consolidation in adult AML patients under 65 years is not associated with survival benefit: real-world data from the German SAL-AML registry. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 149, 4611–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R.J. et al. (1997). Intensified Post-Remission Chemotherapy for Adults with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: An Update of CALGB 8525. In: Büchner, T., Schellong, G., Ritter, J., Creutzig, U., Hiddemann, W., Wörmann, B. (eds) Acute Leukemias VI. Haematology and Blood Transfusion / Hämatologie und Bluttransfusion, vol 38. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Duan, C.; Chen, L.; Chen, S. Efficacy and safety of different doses of cytarabine in consolidation therapy for adult acute myeloid leukemia patients: a network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9509–9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasi, R.; Venditti, A.; Del Poeta, G.; Aronica, G.; Abruzzese, E.; Pisani, F.; Cecconi, M.; Masi, M.; Amadori, S. High-dose chemotherapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: Rationale and results. Leuk. Res. 1996, 20, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zittoun, R.A.; Mandelli, F.; Willemze, R.; de Witte, T.; Labar, B.; Resegotti, L.; Leoni, F.; Damasio, E.; Visani, G.; Papa, G.; et al. Autologous or Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation Compared with Intensive Chemotherapy in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia. New Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelissen, J.J.; Blaise, D. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with AML in first complete remission. Blood 2016, 127, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Du, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F. Effects of post-remission chemotherapy before allo-HSCT for acute myeloid leukemia during first complete remission: a meta-analysis. Ann. Hematol. 2018, 97, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).