Introduction

Medullary thyroid carcinoma is a rare C-cell–derived neuroendocrine tumor accounting for ~0.5-1.5% of thyroid nodules, ~2–5% of thyroid cancers, and ~0.15% of thyroid nodules incidentally discovered during autopsies of subjects who died from thyroid-unrelated conditions [

1]. MTC develops sporadically (i.e., about 75% of cases) or in hereditary contexts [Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type IIA and IIB, and Familial Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma, FMTC] (i.e., about 25%) due to mutations of the proto-oncogene RET (REarranged during Transfection) [

2,

3]. Notably, MTC may be associated with other endocrine tumors such as pheochromocytoma (pheo) and/or primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) due to parathyroid hyperplasia or multiple adenomas, respectively [

4].

Pediatric MTC is exceedingly rare, and inherited cases of MEN 2 are involved in almost all cases [

5].

MTC typically presents as a thyroid nodule, which is occasionally discovered by patients or physicians during a routine clinical examination. Currently, however, thyroid nodules are mainly detected during thyroid-unrelated imaging procedures, such as ultrasound (US) and vascular studies, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR), and positron emission tomography (PET), coupled with CT (PET/CT) or MR (PET/MR). Diagnostic algorithms for MTC are still debated (see below). Notably, however, MTC can metastasize via both lymphatic and hematogenous routes, which contributes to a clinical course that is generally more aggressive than that of differentiated thyroid carcinomas, although it is typically less severe than anaplastic thyroid carcinoma [

6]. Disease-specific mortality at 10 years has been reported to range between 13% and 40%, with overall 10-year survival potentially declining to as low as 50% in some instances [

7]. Several prognostic factors, as older age and advanced tumor stage at presentation, have been associated with increased disease-specific mortality [

8]. Conversely, early detection and the absence of extra-thyroidal extension are generally associated with more favorable outcomes, with survival rates reaching up to 90% over a 35-year period, as reported in some series [

9,

10]. Thyroid parafollicular C-cells produce calcitonin (CT), a highly sensitive circulating biomarker adopted as standard of care for the diagnosis and the follow-up of MTC. Moreover, parafollicular C-cells also produce the CT-precursor ProCT and several peptides, such as CEA, ProGRP, chromogranin A, neuron-specific enolase, and CA19-9, respectively. Despite its pivotal role, CT measurement is subject to several analytical limitations and interferences that may lead to false-positive or false-negative results, complicating the interpretation of CT results and potentially impacting clinical decisions [

11]. Accordingly, some alternative biomarkers have been proposed to complement or even substitute for CT in evaluating MTC patients. Our present paper focuses on established and candidate biomarkers of MTC and discusses the diagnostic performance of different biomarkers, assay methodologies with relative pitfalls, and proposes clinical algorithms integrating different biomarkers.

Biomarkers of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma

Calcitonin

Parafollicular thyroid C-cells uniquely secrete CT, a 32-amino-acid peptide hormone, making serum CT levels pivotal for the management of MTC. Serum CT assays include radioactive (IRMA) and non-radioactive (IMA) immunometric methodologies, each varying in sensitivity, specificity, and susceptibility to interferences. Further complicating quantification, CT circulates as multiple isoforms and fragments that some assays fail to detect, impairing inter-assay comparability. Notably, new-generation CT assays, particularly the latest immunochemiluminometric assays (ICMAs) on automated platforms, have significantly enhanced analytical performance, thereby improving their clinical utility. In particular, they minimize interferences with CT precursors, enhancing specificity for mature monomeric CT. Moreover, they enable ultrasensitive detection (i.e., <2 pg/mL), allowing for the reliable identification of subtly elevated basal CT levels [

11]. Finally, automated platforms offer high throughput, high sensitivity, and full automation, often integrating with laboratory automation systems. They streamline the testing process, reducing manual intervention and potential errors [

12]. Additionally, CT measurement also presents analytical challenges, which can reduce assay accuracy and inter-method comparability [

13] as detailed here.

Pre-analytical factors: Serum proteases can degrade the CT molecule, necessitating rapid sample processing, refrigerated storage, or use of protease inhibitors [

14].

-Biological confounders: Hypergastrinemia, chronic renal insufficiency, proton-pump inhibitor therapy, pregnancy, and lactation may elevate CT in the absence of MTC [

15].

Moreover, mild CT elevations can be observed in non-malignant conditions, including C cell hyperplasia, various neuroendocrine neoplasms, leukemias, systemic mastocytosis, small cell lung carcinoma, breast and pancreatic cancers, renal dysfunction, primary hyperparathyroidism, autoimmune thyroiditis (even if the latter association is currently debated) [

16,

17].

-Inter-assay variability: Comparability across platforms remains imperfect; consistent laboratory/method use is critical for serial monitoring [

18].

-Immunoassay interferences: Rare heterophilic antibodies may still skew results, underscoring the importance of selecting the appropriate assay and performing repeat testing. Serum pretreatment in heterophilic antibody blocking tubes may detect the interference by lowering the measured CT [

19].

-Hook effect: It may paradoxically underreport CT in patients with very high levels; its mitigation requires serial serum dilution protocols in high-range samples [

20].

Calcitonin Stimulation Testing

In order to increase the specificity of serum CT values and decrease false-positive results, CT stimulation testing was proposed and widely adopted in the past. Traditionally, stimulation with pentagastrin was used with the intention to exclude MTC in patients with basal CT in the grey zone (i.e., 10-100 pg/mL) and to detect a residual response after surgery indicating the need for additional, more aggressive, reinterventions. Since many years, however, pentagastrin was not available, and high-dose CA test (2.5mg/kg) emerged as a reliable and effective stimulus for the diagnosis and follow-up of MTC. It is even more potent than pentagastrin with fewer side effects. Notably, setting reliable cutoffs for either pentagastrin or calcium-stimulated cutoff values was substantially unsuccessful with large differences reported in the literature. Notably, recent studies have proven that stimulating-CT offers no additional value compared to basal-CT, as measured with a new generation immunoassay. In summary, the new generation CT assays improve early detection, reduce false positives, and can simplify diagnostic pathways. Greater baseline sensitivity and gender-specific thresholds significantly narrow the "grey zone," making basal-only protocols viable in many cases [

1].

Calcitonin Thresholds and Clinical Decision Limits

Notably, men and women exhibit consistent differences in basal CT levels, driven by biological factors that significantly inform both clinical interpretation and diagnostic thresholds. These differences are likely related to the different mass of C-cells in males compared to females (ratio ~2:1). Additionally, testosterone may stimulate C-cell proliferation. In contrast, no analogous effect is observed with female sex hormones [

21]. An extensive population study (n ≈10500 subjects) showed a mean CT value of ~2.3 pg/mL in men vs. ~1.9 pg/mL in women (p<0.001), even after excluding confounding conditions, with 95

th percentile reference thresholds for healthy non-smoking adults are ~5.7 pg/mL in men and ~3.6 pg/mL in women, respectively. Accordingly, gender-specific CT thresholds are required to avoid biochemical misclassifications [

22]. Alike, gender-specific peak thresholds should be generated for pentagastrin/calcium stimulation tests [i.e., ~80 pg/mL (women) vs. ~500 pg/mL (men)] [

21]. Finally, smoking slightly elevates CT in males (non-smoker ~2.4 pg/mL vs. smoker ~2.8 pg/mL; p<0.001) while women show no smoking-related increase. Thus, in men, reference thresholds may be further stratified by smoking status (e.g., smoker cut-off ~7.9 pg/mL versus 2.8 8 pg/mL) [

22]. All in all, applying higher male thresholds reduces unnecessary follow-ups and surgeries, while maintaining high detection rates for MTC and minimizing overdiagnosis. Accordingly, false-positive rates ~1.8% in men vs. ~1.3% in women were reported in a large screening cohort [

23]. Importantly, with new sensitive assays and sex-adjusted interpretation, many guidelines consider avoiding stimulation tests in truly basal-negative individuals (i.e., basal only protocols). Meta-analyses cite pooled basal CT sensitivity/specificity ~99%, reinforcing the effectiveness of these improved tests [

24]

Procalcitonin

Procalcitonin (ProCT) is a 116-amino-acid prohormone, normally cleaved to CT in thyroid parafollicular C cells. Under normal physiological conditions, ProCT expression is limited to thyroid C cells and circulates at low concentrations. Unlike CT, ProCT exhibits a stable and concentration-independent half-life of ~20–24 hrs in vivo [

36] and it shows excellent in vitro stability when collected as serum or plasma samples, reducing pre-analytical variability [

37]

. Kratzsch and colleagues tested two fully automated and one non-automated CT assays, comparing these results with those from ProCT (Brahms Kryptor) [

38]

. They evaluated preanalytical factors and ProCT cross-reactivity in serum samples from 437 patients presenting with clinical conditions linked to elevated CT levels. Their study also included 60 post-thyroidectomy patients and established CT cutoff values for pentagastrin stimulation tests in 13 patients with chronic kidney disease and 10 patients with MTC.

Their findings revealed several key points. Serum CT concentrations showed significant degradation when stored at room temperature for over 2 hours or at 4°C for more than 6 hours. The cutoff values for both baseline and stimulated CT varied depending on the specific disease state and assay methodology employed. Proton pump inhibitor treatment was the most common cause of elevated CT levels. Notably, ProCT concentrations were elevated in MTC patients compared to those with chronic kidney disease who did not have concurrent infections.

The study concluded that elevated CT concentrations occur frequently in patients without MTC and advocated for incorporating ProCT assessment when evaluating unexplained CT elevations in ambiguous clinical scenarios. Furthermore, ProCT testing proves valuable when CT measurements are compromised by preanalytical or analytical limitations, or when CT values fall within indeterminate ranges [

39]. Moreover, in contrast with the weak agreement between different CT assays [

12,

40], a high degree of agreement was demonstrated between ProCT assays, making it possible to establish general ProCT thresholds in a clinical setting. Lippi and colleagues showed that 10 fully automated commercial ProCT assays deliver acceptable correlations in 176 routine lithium-heparin plasma samples, suggesting that other ProCT assays may also be appropriate for the purpose [

41]

. All in all, ProCT circumvents many of the analytical and pre-analytical problems associated with CT measurement, and consequently, has recently emerged as a potential complementary or alternative MTC biomarker.

Procalcitonin in Diagnosis and Monitoring of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma

Multiple studies have robustly demonstrated that ProCT identifies MTC cases with high diagnostic accuracy (

Table 2).

Algeciras-Schimnich and colleagues firstly demonstrated the potential role of ProCT as an alternative biomarker of MTC in a study including 835 patients with active MTC, cured MTC, neuroendocrine tumors, active and cured follicular cell-derived thyroid carcinoma, benign thyroid diseases, mastocytosis, and normal volunteers, respectively [

42]. The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed no significant difference in diagnostic performance between CT and ProCT. A comparison of CT and ProCT in stability studies showed that CT was very unstable in vitro (i.e., a decrease of 35-50% from the original value 24 hours after sampling). In contrast, ProCT concentrations did not significantly change during this time.

Giovanella and colleagues evaluated the role of routine measurement of ProCT in a sample of 1236 patients and reported serum CT levels > 10 pg/mL in 14 (1.1%) patients [

43]. Among them, two were found to have MTC, one a C-cell hyperplasia, while MTC was excluded in the remaining patients by subsequent clinical and histological follow-up. Basal levels of CT were >100 pg/mL in two MTC patients, and pentagastrin-stimulated CT was > 100 pg/mL in two MTC patients and two non-MTC patients, respectively. Moreover, basal and stimulated ProCT values were elevated in only two MTC patients, resulting in 100% accuracy. As the main result, ProCT was detectable in MTC patients and undetectable in the remaining ones (100% sensitivity and 100% negative predictive values).

In a large prospective study, Giovanella and colleagues evaluated 2705 patients with thyroid nodules measuring only ProCT as a screening test. A ProCT cutoff of 0.155 pg/mL yielded 100% sensitivity and 99.7% specificity in diagnosing MTC [

44].

Finally, Clausi and colleagues recently reported results obtained in 478 patients undergoing thyroidectomy [

48]. Serum levels of ProCT and CT were measured before surgery. Overall, 23/478 (4.8%) patients tested positive for MTC. CT with a cut-off > 10 pg/mL demonstrated sensitivity 0.91, specificity 0.98, PPV 0.70, and NPV 0.99. ProCT showed sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 0.87, 0.96, 0.56, and 0.99 using a cutoff of 0.04 ng/mL, and 0.78, 0.98, 0.72, and 0.99. using the cut-off of 0.07 ng/mL, respectively. Interestingly, 80.9 % of patients with a CT value between 10 and 100 pg/mL would have been correctly identified as MTC or non-MTC by positive or negative ProCT using the cut-off 0.04 ng/mL. The authors concluded that CT demonstrates superior sensitivity compared to ProCT as a diagnostic marker for MTC, but implementing a two-step approach with ProCT as an adjunctive marker can enhance diagnostic precision and prevent overtreatment, especially when CT serum concentrations fall between 10 and 100 pg/m.

Such results are in line with those obtained by Giovanella and colleagues measuring CT and ProCT in 16 patients with active (i.e., primary tumour before surgery or post-surgical recurrent disease) and 23 with inactive (i.e., complete remission) MTC, 125 patients with non-MTC benign thyroid disease, and 62 patients with non-MTC thyroid cancers [

49]. Both CT and ProCT median values were significantly higher in active (94 pmol/L and 1.17 ng/mL ) than inactive (0.28 pmol/L ng/mL and 0.06 ng/mL), benign (0.37 pmol/L and 0.06 ng/mL) and malignant non-MTC diseases (0.28 pmol/L and 0.06 ng/mL), respectively. Notably, undetectable ProCT was found in five non-MTC patients with false-positive CT results. The authors concluded that, at the very least, ProCT is useful in patients with positive CT results, as negative ProCT values securely exclude active MTC (i.e., a rule-out test). As both markers are available in the same automated platforms, a reflex or reflective strategy can be easily adopted to refine the laboratory diagnosis.

Postoperative monitoring also benefits from ProCT measurements: among 55 patients under surveillance, a 0.32 ng/mL threshold achieved 92% sensitivity and 98% specificity for residual or recurrent disease [

45]

More recently, Censi and colleagues retrospectively evaluated 90 MTC patients during post-operative follow-up and found a strong relationship between CT and ProCT, corroborating the relevant role of ProCT as an adjunctive biomarker to CT, especially to exclude MTC structural recurrences in patients with a slight to moderate increase of CT concentrations [

46]. Importantly, the ProCT to CT ratio has also demonstrated predictive value for progression-free survival, further validating its clinical utility as a prognostic indicator [

50]. Collectively, available evidence indicates that ProCT measurement offers excellent diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and prognostic information, while providing significant preanalytical and analytical advantages. Notably, a recent meta-analysis including 5817 individuals (335 with MTC) reported a pooled sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 100% for ProCT in MTC, providing robust evidence in favor of the use of ProCT in diagnosis and follow-up of MTC [

47].

Indeed, ProCT levels can become markedly elevated during severe bacterial infections and sepsis due to ectopic production by non-thyroidal tissues. The Food and Drug Administration has approved ProCT assays for risk stratification in critically ill patients at risk for severe sepsis and septic shock [

51]. Nonetheless, elevations due to bacterial infections necessitate careful interpretation, as in inflammatory states, ProCT can markedly increase [

52].

Table 3 summarizes the role of ProCT in different clinical settings and practical advantages.

Regarding the sensitivity of ProCT, which has been found inferior to that of CT by some authors, it is worth noting that serum CT measurement is integral (and often the only diagnostic biomarker) in establishing the diagnosis and referring patients to surgery. Obviously, the diagnostic sensitivity of CT is biased toward 100% (i.e., a slight increase of CT levels prompts diagnostic work-up, while normal CT, in the presence of detectable ProCT, not measured at that time, would not have required further controls. Accordingly, the best performance an alternative marker can achieve is equal to that of CT, and for statistical reasons, it cannot surpass the current CT standard. Indeed, a potential reservation against replacing CT monitoring as the gold standard for MTC may be related to the opposition/resistance of the medical community. Additionally, ProCT measurement is FDA-approved as a marker of lower respiratory tract infection. Given the rarity of MTC and the significant work required to collect medical device documentation, as well as the associated costs of obtaining a change in approved indications, the device manufacturer(s) continue to favor the off-label use of ProCT for MTC. All considered, it currently seems reasonable to initially adopt ProCT as a complementary marker in patients with thyroid nodules and positive CT testing (i.e., a rule-out test) and in MTC patients with unclear postoperative serial CT measurement patterns.

Carcinoembryonic Antigen

Medullary thyroid carcinoma arises from parafollicular C cells, which, in addition to CT and ProCT, express and release CEA in approximately half of cases. CEA is a ~200 kDa onco-fetal glycoprotein involved in cell adhesion and part of the CEACAM immunoglobulin family. CEA is normally expressed during fetal gastrointestinal development, with minimal expression in healthy adults (<2–4 ng/mL) [

53]. It is typically quantified via standardized immunometric assays, which are analytically robust, reproducible, and less affected by interferences and the hook effect seen with CT. Notably, however, CEA measurement is affected by benign conditions (i.e., inflammation, smoking, liver dysfunction conditions) and other malignancies (colorectal or lung cancer), requiring cautious interpretation. In particular, postoperative CEA is widely adopted as a reliable tumor marker and prognostic factor for colon cancer [

54]. Even if CEA is not a specific MTC biomarker, its measurement remains useful in assessing the extension and progression of the disease before and after thyroidectomy. Baseline CEA levels are low in early, thyroid-limited MTC, precluding its use in screening and early diagnosis of MTC. However, CEA remains a valuable adjunct marker in monitoring patients after surgery and stratifying the risk of recurrence and death in patients with advanced disease, respectively. Preoperative CEA values >30 ng/mL indicate a larger size of the primary tumor and extra-thyroid tumor extension. Moreover, CEA values greater than 100 ng/mL are associated with lymph node involvement, distant metastases, and a poorer prognosis [

55]. Accordingly, serum CEA should be systematically measured before surgery in patients with confirmed or suspected MTC to inform the extent of resection and, particularly, lymph-node dissection (s) [

56]. Following surgery, MTC patients require evaluation for residual disease presence, localization of metastases, and progressive disease identification. Postoperative restaging is essential to distinguish low-risk MTC patients from those at high risk for disease recurrence. Post-operative CT and CEA levels should be systematically documented. Postoperative undetectable CT levels correlate with favorable outcomes. In patients with basal serum CT levels below 150 pg/mL after thyroidectomy, persistent or recurrent disease is typically limited to cervical lymph nodes. Conversely, postoperative serum CT elevation above 150 pg/mL necessitates comprehensive imaging studies, including neck and chest CT, contrast-enhanced MRI, hepatic US, bone scintigraphy, bone MRI, and PET/CT. The integration of CEA measurement is useful in this context, as post-thyroidectomy failure of CEA levels to normalize—or an increase in levels—suggests residual disease, offering an early warning for recurrence even when CT remains low [

1]. Notably, CEA demonstrates relatively stable kinetics compared to CT, displaying less diurnal fluctuation and thus serving as a robust indicator of tumor mass. Additionally, a rising CEA, even in the absence of a CT increase, suggests a more aggressive disease phenotype (i.e., dedifferentiated disease) and may prompt more comprehensive metastatic workups using advanced imaging modalities, such as

18F-FDG PET/CT [

57,

58]. Among patients with advanced disease, structural disease growth rate can be estimated and monitored through sequential imaging studies using RECIST criteria to document tumor size increases over time, and by measuring serum CT or CEA levels at multiple time points to determine tumor marker doubling time (DT) [

1].

Doubling Time of Calcitonin and Carcinoembryonic Antigen

Calcitonin and CEA DTs are used to assess tumor burden and the aggressiveness of MTC and predict the likelihood of recurrence or progression. They help monitor the effectiveness of treatment and guide decisions about further treatment strategies. Patients with shorter DTs may be considered higher risk and may benefit from intensified surveillance and/or additional imaging and/or treatments. CT and CEA levels are assumed to increase exponentially in MTC, doubling over a specific timeframe. Reliable DT calculation requires a well-standardized procedure. First, serial tumor marker measurements (i.e., every 6 months) with a minimum of four values (ideally over 2 years) are recommended. Second, methodological consistency is essential: all measurements should utilize the same laboratory and assay platforms to ensure accuracy. Third, DT should be calculated using the formula: DT = ln(2)/b, where "b" represents the exponential growth rate constant derived from regression analysis of measured CT and CEA levels. Fourth, values below the limit of quantitation (LoQ) of the assay are reported as “equal to the LoQ” (i.e., if the LoQ of a CT assay is 2 pg/mL and the patients’ value is rendered as <2 pg/mL the value inputted for calculation will be 2 pg/mL). Finally, undetectable values and detectable values that do not double are designated as "never doubled". Multiple reliable platforms are freely available to calculate DTs: the Kuma Hospital DT Calculator (Kuma Hospital, Japan) is widely employed and was also adopted by the authors of the present review [

59]. A note of caution is necessary when using DTs in clinical practice, as they can vary significantly between patients and other factors (i.e., tumor grade, stage, and site of metastasis). Accordingly, DT results should always be considered in the general clinical context, taking into account the results of other diagnostic tools. Interpretation criteria of CT and CEA doubling times are summarized in

Table 4.

Finally, absolute levels of CT and CEA, as well as the ratio of DTs, are very useful in guiding advanced molecular imaging in patients with relapsing or advanced MTC. In general,

8F-DOPA PET/CT appears to be superior to

18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting and locating lesions in patients with recurrent MTC, especially when CT exceeds 150 pg/mL, CEA is ≥ 5 ng/mL, or CT-DTs range between 1 and 2 years. However,

18F-FDG PET/CT showed a better accuracy in patients with very high CT levels (>500 pg/mL), those with a disproportionate CEA increase compared to CT, and/or markers DTs < 1 year. Accordingly, a rationale and consequential use of biomarkers and imaging could improve the clinical reassessment and better identify high-risk patients who require more careful surveillance [

60,

61,

62].

Pro-Gastrin-Releasing Peptide

As reported in previous sections of the present paper CT is the standard of care in diagnosis and monitoring of MTC, while serum ProCT is a potential to alternative or at least as a complementary test to CT in unclear cases being free from analytical limitations and interferences that may lead to false positive or negative CT results. The Pro-Gastrin-Releasing Peptide (ProGRP) is a stable precursor of gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP), a neuropeptide involved in tumor growth and differentiation. ProGRP is principally employed as a tumor marker of small cell lung cancer [

63]. ProGRP is generally measured using fully automated, non-competitive IMAs, which provide high reproducibility. In addition, ProGRP offers pre-analytical advantages: it is stable in serum, is not subject to the hook effect, and is measurably preserved even with delayed processing. To date, however, no reference method or international standard has been identified in the literature regarding the analytical performance of IMAs, and comparisons between them are sparse [

64]. More recently, ProGRP has emerged as a promising adjunct biomarker in MTC, with initial studies demonstrating diagnostic performance similar to that of established markers (

Table 6).

Overall, ProGRP has only moderate sensitivity (~80%) and cannot be used in MTC screening and diagnosis, considering the sensitivity of ~100% robustly demonstrated by either CT or ProCT. Considering the high specificity, it should be considered to rule out false-positive CT results, but again, ProCT already demonstrated a quite absolute negative predictive value in patients with indeterminate CT results. Interestingly, ProGRP correlates with metastatic burden, and proGRP levels are significantly higher in patients with nodal or distant metastatic MTC than in those with limited disease. Additionally, ProGRP levels drop post-surgery, aligning with effective resection, and serial ProGRP measurements mirrored imaging responses more closely than CT or CEA in patients under tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy (i.e., vandetanib), making it a potential early indicator of therapy response or resistance [

66]. Most available studies, however, were retrospective with small sample sizes, although they were conducted in expert centers, and current evidence remains fragmented and insufficient to support or refute its implementation in clinical protocols. Generally speaking, serum ProGRP is likely of limited value in the diagnosis of MTC; however, promising preliminary data suggest a useful application in advanced disease, especially in therapy response assessment. All in all, ProGRP can currently be considered as a candidate MTC biomarker, and its inclusion in advanced MTC management protocols needs studies in large prospective cohorts of patients with advanced disease and active systemic treatment.

Carbohydrate Antigen 19.9

Carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (CA 19.9) is a sialyl Lewis-A glycan, classically used in monitoring pancreatic and gastrointestinal malignancies. Its aberrant expression was reported in subgroups of MTC characterized by aggressive or metastatic behavior [

73]. CA 19.9 is measured by immunoassays employing monoclonal antibodies against the sialyl Lewis-A epitope. Assays are standardized for digestive cancers; however, inter-method variability persists due to epitope heterogeneity, differences in proprietary antibodies, and technical variations. Additionally, approximately 5-10% of individuals lack the Lewis antigen and cannot produce CA 19-9, yielding potentially false-negative results [

74]. In addition to pancreatic gastrointestinal malignancies, CA 19.9 elevations may be noted in benign hepatobiliary and pancreatic diseases and benign respiratory diseases, which may complicate interpretation in MTC patients [

73]. Notably, CA 19.9 is not sensitive for early or localized MTC, as only 5–6% of intra-thyroid tumors overexpress it, and fewer present with elevated CA 19.9 serum levels. However, in advanced MTC, serum CA 19.9 increases, and its concentration correlates with structural disease progression. Immunohistochemical analyses confirmed CA 19.9 expression in metastatic MTC tissue, affirming the tumor origin of the circulating marker [

75]. In a series of 122 MTC patients, mean CA 19.9 levels were significantly higher in those with progressive disease (median ~21.4 U/mL vs ~7.3 U/mL; p=0.01) and in those who died from MTC (p<0.001) [

73] Additionally, prospective data identify CA 19.9 positivity and fast CA 19.9 DT (i.e., <6 months) in advanced MTC as independent predictors of mortality, regardless of imaging findings. In these patients, systemic treatment (e.g., with cabozantinib or vandetanib) may be considered sooner than imaging alone would indicate [

76]. In conclusion, due to limited sensitivity and specificity, CA 19.9 cannot replace established MTC biomarkers (i.e., CT and CEA) but may serve as a useful adjunct in select CA 19.9-positive cases. Its elevation and rapid doubling convey increased mortality risk and may prompt earlier therapeutic intervention independent of imaging findings. Additional multicentric, prospective studies are needed to define optimal thresholds, assay standardization, and integration into MTC care algorithms.

Measurement of MTC Biomarkers in Fine-Needle Aspiration Washouts

The measurement of CT in fine-needle aspiration washout fluids (FNA-CT) from thyroid nodules and/or lymph nodes suspected of MTC or lymph nodes has been proposed to circumvent limitations of cytology in detecting MTC with a sensitivity of only 55% to 65%. Despite numerous criticisms (i.e., interferences, lack of standards, analytical variability of different assays) affecting the accuracy of the results and making it hard to compare studies, all available studies show significantly high sensitivity and specificity of FNA-CT, clearly better than that of cytopathology

(Table 7) [

77]

.

Obviously, the appropriate sampling is key, and samples should be representative of the approached lesion in the thyroid nodules, thyroid bed, or lymph node, respectively [

83]. Unlike FNA cytology, however, diagnosis remains possible using FNA-CT even when no thyroid cells are aspirated, since CT exhibits high concentrations both within and surrounding the lesion area [

84]

Finally, detectable levels of FNA-CT (i.e., higher than the functional sensitivity of the employed assay) were found in most non-medullary thyroid nodules, likely due to normal C-cells entrapped in the FNA sample, especially from the middle/upper thyroid lobes, highlighting the relevance of an appropriate cutoff selection [

83].

Relevant practical points for FNA-CT measurement and interpretation are summarized in

Table 8.

Recently, ProGRP measurement was tested in 212 patients with 235 thyroid nodules, classified into chronic thyroiditis, nodular goiter, papillary thyroid carcinoma, thyroid follicular neoplasm, follicular thyroid carcinoma, and MTC. Serum ProGRP and FNA-ProGRP were measured. The median serum ProGRP concentration was 124.40 pg/mL in MTC, significantly higher than in other tested groups. The serum ProGRP cutoff value was 68.30 pg/mL, yielding 53.85% sensitivity, 96.98% specificity, and a kappa value of 0.51 in MTC. The median concentration of FNA-ProGRP in MTC nodules was 2096.00 pg/mL, significantly higher than in other groups. ROC analysis of MTC nodules versus non-MTC nodules revealed a cutoff value of 22.77 pg/mL, achieving 94.12% sensitivity, 98.27% specificity, and a kappa value of 0.85. The authors suggested FNA-ProGRP measurement as an ancillary method for differential diagnosis between MTC and non-MTC thyroid nodules [

67].

Further studies, however, are required to confirm or refute this preliminary observation and accurately evaluate the diagnostic advantage over FNA-CT. As a consequence, FNA-ProGRP measurement should only be considered in the context of clinical trials.

Integrated Use of Circulating Markers of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma

This paper presents the biochemical and analytical characteristics of currently available MTC biomarkers, analyzing their diagnostic performance and clinical applications. Algorithms for the rational and integrated use of various biomarkers, as outlined in current guidelines, are presented below.

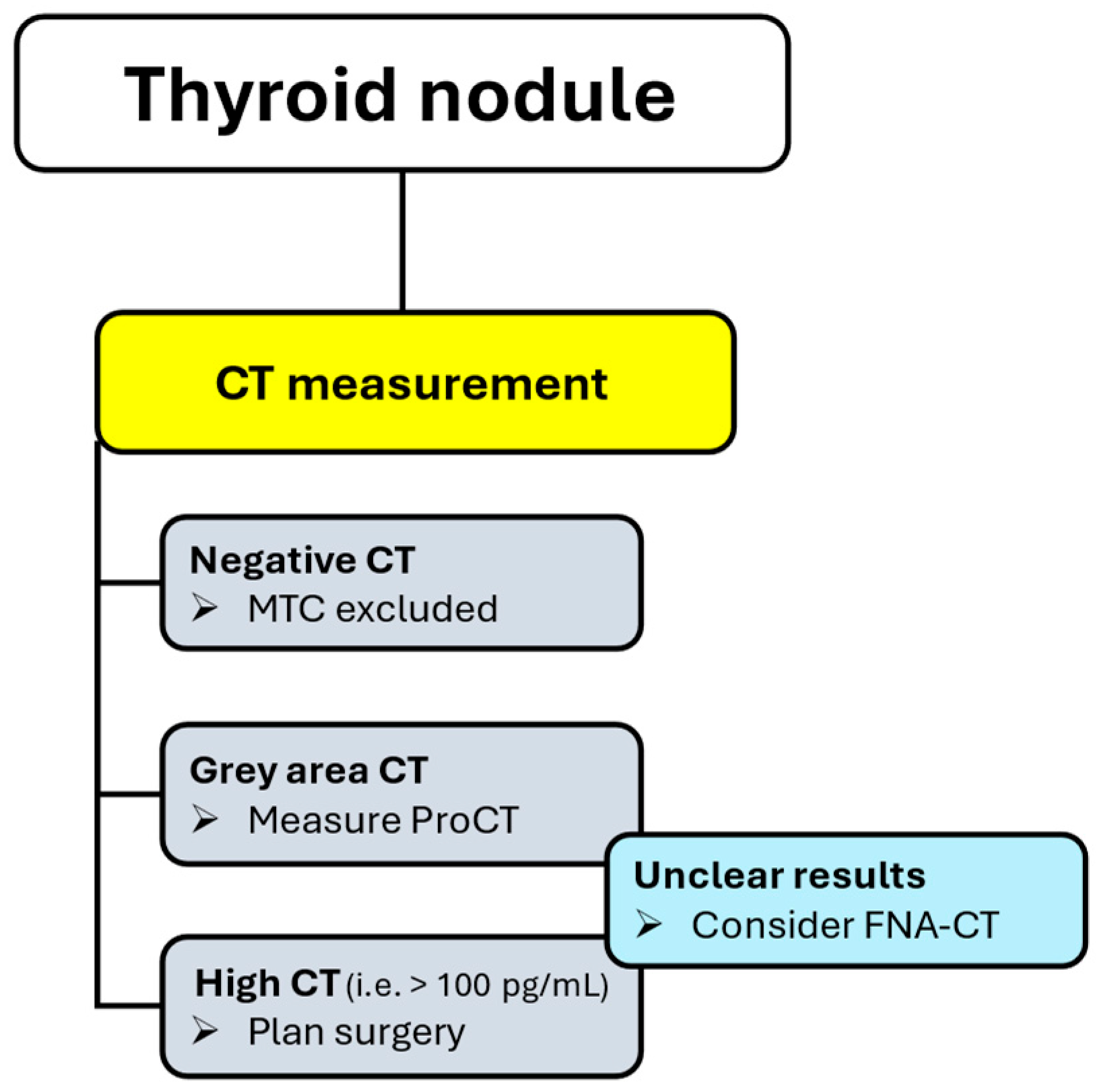

Screening and Diagnosis of MTC

Calcitonin proved to be a useful screening test for the presence of MTC in patients with thyroid nodules, exhibiting a high diagnostic sensitivity. However, this practice is debated due to the low prevalence of MTC and the non-negligible rate of false-positive CT results [

1].

Recently, ProCT has been shown to be highly accurate in excluding MTC in patients with indeterminate CT values (i.e., 10-100 pg/mL), making a two-step procedure actionable. In turn, human, social, and economic costs associated with false positive CT results (i.e., imaging, FNA, additional laboratory tests) will be reduced by applying a reflex test procedure and safety rule out MTC in patients with undetectable ProCT (

Figure 1) [

47].

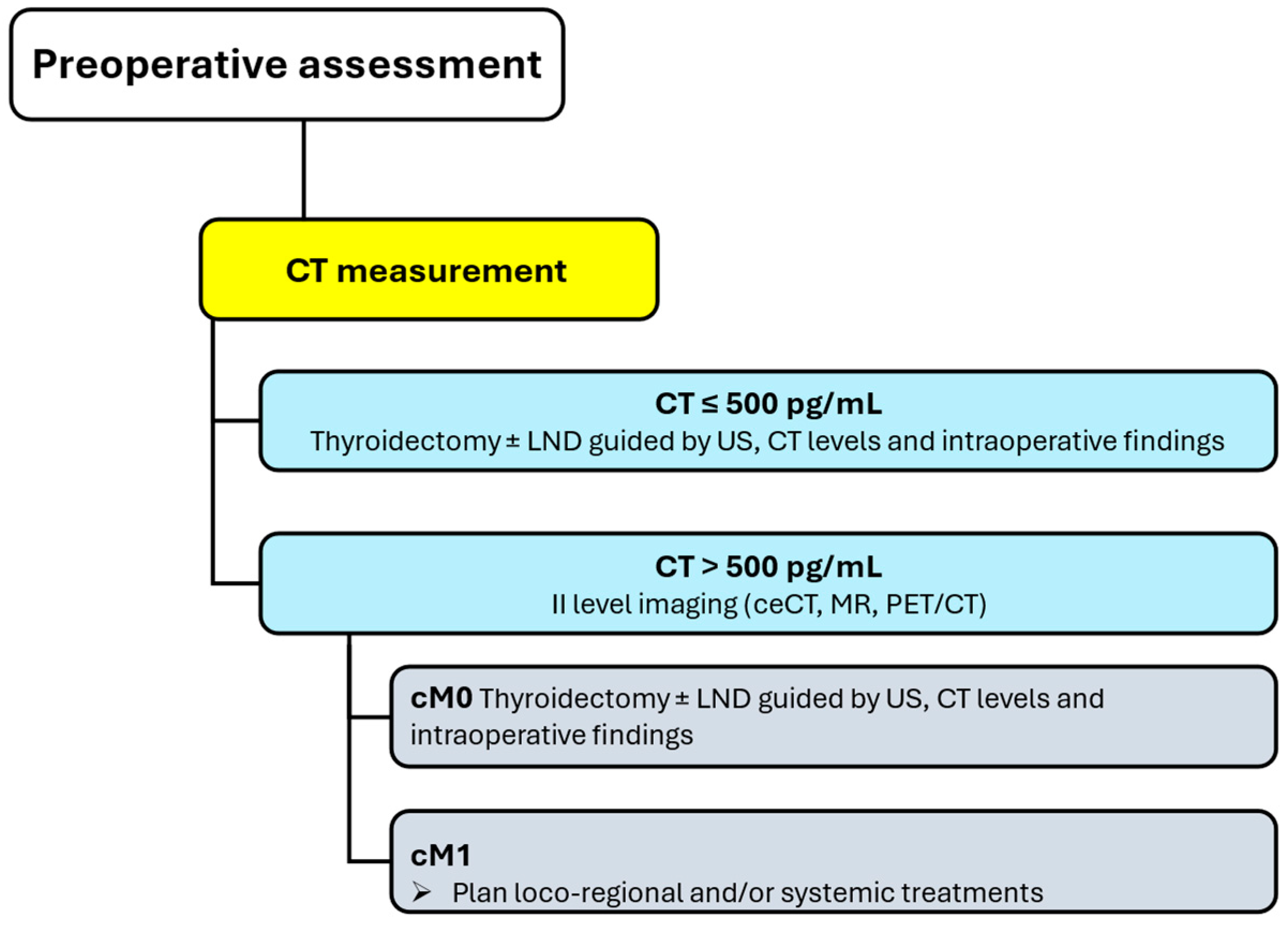

Preoperative Assessment

Patients with diagnosed MTC should be assessed before surgery to map neck lymph nodes and detect/exclude distant metastasis. Distant metastases are unlikely in patients with negative US and CT levels below 500 pg/mL: in such cases, no additional imaging is recommended, and total thyroidectomy is planned with additional lymph node dissections informed by US, absolute CT levels, and intraoperative findings. The risk of advanced disease and distant metastasis significantly increases in patients with CT levels greater than 500 pg/mL, and level II imaging (i.e., ceCT, MR, PET/CT) is required to refine disease staging and detect or exclude distant metastases (

Figure 2) [

1].

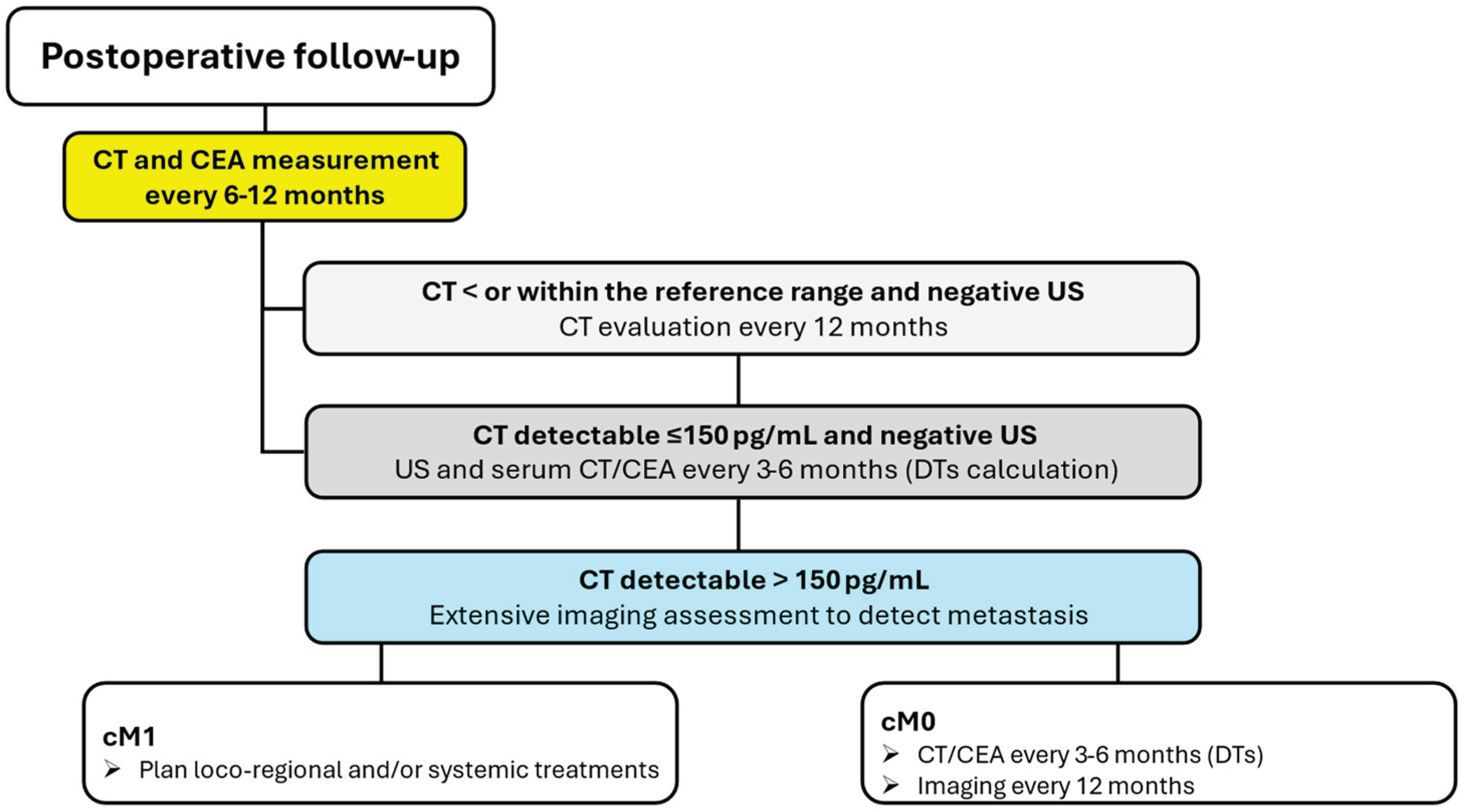

Post-Operative Monitoring

Following surgery, serum CT and CEA levels should be measured 3 months postoperatively, and if undetectable or within normal range, should be measured every 6 months for 1 year, and then annually. In patients with detectable serum levels of CT and CEA following thyroidectomy, the levels of the markers should be measured at least every 6 months to determine their doubling time. Patients with elevated postoperative serum CT levels of less than 150 pg/mL should undergo a physical examination and US of the neck. If these studies are negative, the patients should be followed with physical examinations, measurement of serum levels of CT and CEA, and US every 6 months. If the postoperative serum CT level exceeds 150 pg/mL, patients should be examined by imaging procedures, including neck US, ceCT, MR, or three-phase ceCT of the liver, and PET/CT (

Figure 3) [

1].

Complementary Biomarkers

As extensively discussed, additional markers to CT and ProCT are available and can provide useful insights in more selected conditions. While not suitable for initial screening and diagnosis due to limited sensitivity, CEA is a valuable adjunct in the management of MTC. In particular, it excels in staging, risk stratification, and tailoring the extent of surgery. Moreover, it complements CT during postoperative surveillance, providing additional prognostic and recurrence-detection insight, particularly in cases of biochemical discordance. Basically, CEA measurement should be combined with CT measurement during postoperative follow-up. CA 19.9 may assist prognostic stratification in patients with advanced disease, while ProGRP is a candidate biomarker for advanced MTC monitoring during tyrosine-kinase inhibitors, even if definitive data are needed before its introduction in clinical practice.

Limitations and Perspectives

Currently, fully automated immunoassays are widely used to evaluate MTC biomarkers across various analytical platforms, which are commercially available from different manufacturers. These highly automated systems offer an optimal balance of high throughput, rapid turnaround time, minimal sample volume, and cost-effectiveness [

85]. Although significant advances have been made over the years in the analytical performance of various immunoassays, substantial inter-method variability still persists [

86]. This variability necessitates the use of method-specific reference intervals, making it challenging to compare results obtained from different assays. Consequently, the use of the same immunoassay method is essential for reliable patient follow-up [

85]. Although extensive research has been conducted over the years, challenges remain in terms of standardization and harmonization. Variability between methods can often be attributed to the use of primary antibodies with different epitope specificities. However, significant discrepancies have also been observed between assays that utilise the same monoclonal antibodies, as seen in CA 19-9 assays employing the Centocor monoclonal antibody, indicating that other methodological factors also play a critical role [

87]. In such cases, elements related to the assay's architectural format must be considered when assessing inter-method variability. These include differences in incubation times, reaction kinetics, washing procedures, and the nature of the tracer system used. Together, these parameters influence the final numerical result, potentially leading to a lack of interchangeability between methods. To improve comparability and progress towards harmonisation and standardisation of immunoassays for markers of MTC, efforts should focus on the development and implementation of reference materials and reference measurement procedures for each analyte. In addition to the development of methodological references, a key factor for harmonisation between methods is the commutability of control materials, particularly those used in External Quality Assessment (EQA) schemes [

86,

88]. In order to improve this aspect, it is necessary to develop control materials prepared from authentic human samples or with advanced reconstitution technologies; check the commutability of EQA materials before distribution to laboratories (i.e., according to guidelines); use materials that are traceable to primary reference standards, where available, and, over all, promote collaborations between reagent manufacturers, laboratories and international laboratory medicine societies to create reference networks. Investment in this aspect would bring not only technical but also clinical benefits, improving the reliability of diagnostic results.

Table 9 summarizes the main aspects of the pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical phases concerning the tests used for determining circulating blood biomarkers of medullary thyroid carcinoma.

Conclusions

We provided a robust analysis and a structured guide for serum biomarker deployment in MTC management, balancing established markers (i.e., CT and CEA) and emerging tools to enhance clinical decision-making (i.e., ProCT, CA 19.9, ProGRP). The currently available panel of different markers is well-suited to manage MTC patients and guide treatments. Methods standardization should be further ameliorated and large prospective multicentric validation is desirable to refine clinical thresholds of different markers, evaluate candidate biomarkers, and address rare clinical scenarios, as CT-negative MTC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.; methodology, L.G.; data curation, L.G. F.D.A., and P.P.O.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.; writing—review and editing, L.G., F.D.A., and P.P.O.; supervision, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wells, S.A.; Asa, S.L.; Dralle, H.; Elisei, R.; Evans, D.B.; Gagel, R.F.; Lee, N.; MacHens, A.; Moley, J.F.; Pacini, F.; et al. Revised American Thyroid Association Guidelines for the Management of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Thyroid 2015, 25, 567–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrone, A.; Gambale, C.; Prete, A.; Elisei, R. Sporadic Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: Towards a Precision Medicine. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donis-keller, H.; Dou, S.; Chi, D.; Carlson, K.M.; Toshima, K.; Lairmore, T.C.; Howe, J.R.; Moley, J.F.; Goodfellow, P.; Wells, S.A. Mutations in the RET Proto-Oncogene Are Associated with MEN 2a and FMTC. Hum Mol Genet 1993, 2, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, L.M.; Marsh, D.J.; Robinson, B.G.; Schuffenecker, I.; Zedenius, J.; Lips, C.J.M.; Gagel, R.F.; Takai, S.I.; Noll, W.W.; Fink, M.; et al. Genotype-Phenotype Correlation in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2: Report of the International RET Mutation Consortium. J Intern Med 1995, 238, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanso, G.E.; Domene, H.M.; Garcia Rudaz, M.C.; Pusiol, E.; De Mondino, A.K.; Roque, M.; Ring, A.; Perinetti, H.; Elsner, B.; Iorcansky, S.; et al. Very Early Detection of RET Proto-Oncogene Mutation Is Crucial for Preventive Thyroidectomy in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2 Children: Presence of C-Cell Malignant Disease in Asymptomatic Carriers. Cancer 2002, 94, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, E.; Romei, C.; Biagini, A.; Sabini, E.; Agate, L.; Mazzeo, S.; Materazzi, G.; Sellari-Franceschini, S.; Ribechini, A.; Torregrossa, L.; et al. Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: From Clinicopathology to Genetics and Advanced Therapies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2017, 13, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.B.; Ljungberg, O. Mortality from Thyroid Carcinoma in Malmö, Sweden 1960–1977. A Clinical and Pathologic Study of 38 Fatal Cases. Cancer 1984, 54, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrone, A.; Gambale, C.; Prete, A.; Piaggi, P.; Cappagli, V.; Bottici, V.; Romei, C.; Ciampi, R.; Torregrossa, L.; De Napoli, L.; et al. Impact of Advanced Age on the Clinical Presentation and Outcome of Sporadic Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GHARIB, H.; McCONAHEY, W.M.; TIEGS, R.D.; BERGSTRALH, E.J.; GOELLNER, J.R.; GRANT, C.S.; van HEERDEN, J.A.; SIZEMORE, G.W.; HAY, I.D. Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: Clinicopathologic Features and Long-Term Follow-Up of 65 Patients Treated During 1946 Through 1970. Mayo Clin Proc 1992, 67, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebebew, E.; Ituarte, P.H.G.; Siperstein, A.E.; Duh, Q.Y.; Clark, O.H. Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: Clinical Characteristics, Treatment, Prognostic Factors, and a Comparison of Staging Systems. Cancer 2000, 88, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.J.; Schaab, M.; Kratzsch, J. Calcitonin as Biomarker for the Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Recent Results in Cancer Research 2015, 204, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieglmayer, C.; Vierhapper, H.; Dudczak, R.; Niederle, B. Measurement of Calcitonin by Immunoassay Analyzers. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007, 45, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiettecatte, J.; Strasser, O.; Anckaert, E.; Smitz, J. Performance Evaluation of an Automated Electrochemiluminescent Calcitonin (CT) Immunoassay in Diagnosis of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Clin Biochem 2016, 49, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, G.; Chen, Q.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Wu, X.; Chen, H. Study on the Degradation Rule of Calcitonin in Vitro in Patients with Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 507, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Herbomez, M.; Caron, P.; Bauters, C.; Cao, C. Do; Schlienger, J.L.; Sapin, R.; Baldet, L.; Carnaille, B.; Wémeau, J.L. Reference Range of Serum Calcitonin Levels in Humans: Influence of Calcitonin Assays, Sex, Age, and Cigarette Smoking. Eur J Endocrinol 2007, 157, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [Hypercalcitoninemia in Conditions Other than Medullary Cancers of the Thyroid] - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8734284/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Cvek, M.; Punda, A.; Brekalo, M.; Plosnić, M.; Barić, A.; Kaličanin, D.; Brčić, L.; Vuletić, M.; Gunjača, I.; Torlak Lovrić, V.; et al. Presence or Severity of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Does Not Influence Basal Calcitonin Levels: Observations from CROHT Biobank. J Endocrinol Invest 2022, 45, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Benfield, P.; Dhillo, W.S.; White, S.; Chapman, R.; Meeran, K.; Donaldson, M.; Martin, N.M. Need for Revision of Diagnostic Limits for Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma with a New Immunochemiluminometric Calcitonin Assay. Clin Chem 2009, 55, 2225–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapetrou, P.D.; Polymeris, A.; Karga, H.; Vaiopoulos, G. Heterophilic Antibodies Causing Falsely High Serum Calcitonin Values. J Endocrinol Invest 2006, 29, 919–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leboeuf, R.; Langlois, M.F.; Martin, M.; Ahnadi, C.E.; Fink, G.D. “Hook Effect” in Calcitonin Immunoradiometric Assay in Patients with Metastatic Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006, 91, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machens, A.; Hoffmann, F.; Sekulla, C.; Dralle, H. Importance of Gender-Specific Calcitonin Thresholds in Screening for Occult Sporadic Medullary Thyroid Cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009, 16, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Jeon, M.J.; Yoo, H.J.; Bae, S.J.; Kim, T.Y.; Kim, W.B.; Shong, Y.K.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, W.G. Gender-Dependent Reference Range of Serum Calcitonin Levels in Healthy Korean Adults. Endocrinology and Metabolism 2021, 36, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broecker-Preuss, M.; Simon, D.; Fries, M.; Kornely, E.; Weber, M.; Vardarli, I.; Gilman, E.; Herrmann, K.; Görges, R. Update on Calcitonin Screening for Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma and the Results of a Retrospective Analysis of 12,984 Patients with Thyroid Nodules. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardarli, I.; Weber, M.; Weidemann, F.; Führer, D.; Herrmann, K.; Görges, R. Diagnostic Accuracy of Routine Calcitonin Measurement for the Detection of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma in the Management of Patients with Nodular Thyroid Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Endocr Connect 2021, 10, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaalkhail, M.; Alorainy, J.; Alotaibi, O.; Albuhayjan, N.; Alnuwaybit, A.; Alqaryan, S.; Alessa, M. Diagnostic Challenges in Calcitonin Negative Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Systematic Review of 101 Cases. Gland Surg 2024, 13, 1785–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeek, H.H.; Groot, J.W.B. de; Sluiter, W.J.; Kobold, A.C.M.; Heuvel, E.R. van den; Plukker, J.T.; Links, T.P.; Group, C.M. and E.D. Calcitonin Testing for Detection of Medullary Thyroid Cancer in People with Thyroid Nodules. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, K.W.; Ensinger, C. “Atypical” Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma with Little or No Calcitonin Expression. Virchows Arch 1998, 433, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaalkhail, M.; Alorainy, J.; Alotaibi, O.; Albuhayjan, N.; Alnuwaybit, A.; Alqaryan, S.; Alessa, M. Diagnostic Challenges in Calcitonin Negative Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Systematic Review of 101 Cases. Gland Surg 2024, 13, 1785–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimboli, P.; Giovanella, L. Serum Calcitonin Negative Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015, 53, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costante, G.; Meringolo, D.; Durante, C.; Bianchi, D.; Nocera, M.; Tumino, S.; Crocetti, U.; Attard, M.; Maranghi, M.; Torlontano, M.; et al. Predictive Value of Serum Calcitonin Levels for Preoperative Diagnosis of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma in a Cohort of 5817 Consecutive Patients with Thyroid Nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugazzola, L. Medullary Thyroid Cancer - An Update. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costante, G.; Durante, C.; Francis, Z.; Schlumberger, M.; Filetti, S. Determination of Calcitonin Levels in C-Cell Disease: Clinical Interest and Potential Pitfalls. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2009, 5, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Etiology. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/282084-overview (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Miyauchi, A.; Onishi, T.; Morimoto, S.; Takai, S.; Matsuzuka, F.; Kuma, K.; Maeda, M.; Kumahara, Y. Relation of Doubling Time of Plasma Calcitonin Levels to Prognosis and Recurrence of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Ann Surg 1984, 199, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbet, J.; Campion, L.; Kraeber-Bodéré, F.; Chatal, J.F. Prognostic Impact of Serum Calcitonin and Carcinoembryonic Antigen Doubling-Times in Patients with Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005, 90, 6077–6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisner, M.; Schmidt, J.; Hüttner, H.; Tschaikowsky, K. The Natural Elimination Rate of Procalcitonin in Patients with Normal and Impaired Renal Function. Intensive Care Medicine, Supplement 2000, 26, S212–S216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisner, M.; Tschaikowsky, K.; Schnabel, S.; Schmidt, J.; Schüttler, J.; Katalinic, A. Procalcitonin - Influence of Temperature, Storage, Anticoagulation and Arterialor Venous Asservation of Blood Samples on Procalcitonin Concentrations. Clin Chem Lab Med 1997, 35, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzsch, J.; Willenberg, A.; Frank-Raue, K.; Kempin, U.; Rocktäschel, J.; Raue, F. Procalcitonin Measured by Three Different Assays Is an Excellent Tumor Marker for the Follow-up of Patients with Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Clin Chem Lab Med 2021, 59, 1861–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanella, L.; Giordani, I.; Imperiali, M.; Orlandi, F.; Trimboli, P. Measuring Procalcitonin to Overcome Heterophilic-Antibody-Induced Spurious Hypercalcitoninemia. Clin Chem Lab Med 2018, 56, e191–e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanella, L.; Imperiali, M.; Ferrari, A.; Palumbo, A.; Lippa, L.; Peretti, A.; Graziani, M.S.; Castello, R.; Verburg, F.A. Thyroid Volume Influences Serum Calcitonin Levels in a Thyroid-Healthy Population: Results of a 3-Assay, 519 Subjects Study. Clin Chem Lab Med 2012, 50, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Salvagno, G.L.; Gelati, M.; Pucci, M.; Lo Cascio, C.; Demonte, D.; Faggian, D.; Plebani, M. Two-Center Comparison of 10 Fully-Automated Commercial Procalcitonin (PCT) Immunoassays. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020, 58, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicia Algeciras-Schimnich; Carol, M.P.; J. Paul Theobald; Mary, S.F.; Stefan, K.G. Procalcitonin: A Marker for the Diagnosis and Follow-up of Patients with Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009, 94, 861–868. [CrossRef]

- Giovanella, L.; Verburg, F.A.; Imperiali, M.; Valabrega, S.; Trimboli, P.; Ceriani, L. Comparison of Serum Calcitonin and Procalcitonin in Detecting Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma among Patients with Thyroid Nodules. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013, 51, 1477–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanella, L.; Imperiali, M.; Piccardo, A.; Taborelli, M.; Verburg, F.A.; Daurizio, F.; Trimboli, P. Procalcitonin Measurement to Screen Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Prospective Evaluation in a Series of 2705 Patients with Thyroid Nodules. Eur J Clin Invest 2018, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimboli, P.; Lauretta, R.; Barnabei, A.; Valabrega, S.; Romanelli, F.; Giovanella, L.; Appetecchia, M. Procalcitonin as a Postoperative Marker in the Follow-up of Patients Affected by Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. International Journal of Biological Markers 2018, 33, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Censi, S.; Manso, J.; Benvenuti, T.; Piva, I.; Iacobone, M.; Mondin, A.; Torresan, F.; Basso, D.; Crivellari, G.; Zovato, S.; et al. The Role of Procalcitonin in the Follow-up of Medullary Thyroid Cancer. Eur Thyroid J 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanella, L.; Garo, M.L.; Ceriani, L.; Paone, G.; Campenni’, A.; D’Aurizio, F. Procalcitonin as an Alternative Tumor Marker of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2021, 106, 3634–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausi, C.; Censi, S.; Zanin, E.; Messina, G.; Piva, I.; Basso, D.; Merante Boschin, I.; Bertazza, L.; Torresan, F.; Iacobone, M.; et al. Combining Procalcitonin and Calcitonin for the Diagnosis of Medullary Thyroid Cancer: A Two-Step Approach. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanella, L.; Fontana, M.; Keller, F.; Verburg, F.A.; Ceriani, L. Clinical Performance of Calcitonin and Procalcitonin Elecsys ® Immunoassays in Patients with Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020, 59, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.A.; Meier, C.; Radimerski, T.; Iten, F.; Kränzlin, M.; Müller-Brand, J.; De Groot, J.W.B.; Kema, I.P.; Links, T.P.; Müller, B. Procalcitonin Levels Predict Clinical Course and Progression-Free Survival in Patients with Medullary Thyroid Cancer. Cancer 2010, 116, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambliss, A.B.; Patel, K.; Colón-Franco, J.M.; Hayden, J.; Katz, S.E.; Minejima, E.; Woodworth, A. AACC Guidance Document on the Clinical Use of Procalcitonin. Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine 2023, 8, 598–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P. How to Best Use Procalcitonin to Diagnose Infections and Manage Antibiotic Treatment. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023, 61, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanala, V.L.; Zubair, M.; Mukkamalla, S.K.R. Carcinoembryonic Antigen. StatPearls 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Arita, A.; Itakura, H.; Fujii, M.; Sekido, Y.; Hata, T.; Fujino, S.; Ogino, T.; Miyoshi, N.; et al. High Postoperative Carcinoembryonic Antigen as an Indicator of High-Risk Stage II Colon Cancer. Oncol Lett 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machens, A.; Ukkat, J.; Hauptmann, S.; Dralle, H. Abnormal Carcinoembryonic Antigen Levels and Medullary Thyroid Cancer Progression: A Multivariate Analysis. Arch Surg 2007, 142, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, I.; Stefanidou, E.; Meditskou-Eythymiadou, S.; Mironidou-Tzouveleki, M.; Manaki, V.; Magra, V.; Laskou, S.; Mantalovas, S.; Pantea, S.; Kesisoglou, I.; et al. A Review of the Significance in Measuring Preoperative and Postoperative Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) Values in Patients with Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma (MTC). Medicina 2021, Vol. 57, Page 609 2021, 57, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raue, F.; Frank-Raue, K. Long-Term Follow-Up in Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma Patients. Recent Results Cancer Res 2025, 223, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terroir, M.; Caramella, C.; Borget, I.; Bidault, S.; Dromain, C.; El Farsaoui, K.; Deandreis, D.; Grimaldi, S.; Lumbroso, J.; Berdelou, A.; et al. F-18-Dopa Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography Is More Sensitive Than Whole-Body Magnetic Resonance Imaging for the Localization of Persistent/Recurrent Disease of Medullary Thyroid Cancer Patients. Thyroid 2019, 29, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KUMA HOSPITAL - Tools. Available online: https://en.kuma-h.or.jp/tools (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Yang, J.H.; Camacho, C.P.; Lindsey, S.C.; Valente, F.O.F.; Andreoni, D.M.; Yamaga, L.Y.; Wagner, J.; Biscolla, R.P.M.; Maciel, R.M.B. The Combined Use of Calcitonin Doubling Time and 18f-Fdg Pet/Ct Improves Prognostic Values in Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: The Clinical Utility of 18f-Fdg Pet/Ct. Endocrine Practice 2017, 23, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Lluch, A.R.; Cuenca-Cuenca, J.I.; Guerrero-Vázquez, R.; Martínez-Ortega, A.J.; Tirado-Hospital, J.L.; Borrego-Dorado, I.; Navarro-González, E. Diagnostic Utility of PET/CT with 18F-DOPA and 18F-FDG in Persistent or Recurrent Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: The Importance of Calcitonin and Carcinoembryonic Antigen Cutoff. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2017, 44, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Chen, L. Management of Medullary Thyroid Cancer Based on Variation of Carcinoembryonic Antigen and Calcitonin. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Salvia, A.; Fanciulli, G. Progastrin-Releasing Peptide As a Diagnostic Biomarker of Pulmonary and Non-Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Endocr Res 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz de Medrano, J.I.; Laguna, J.; Julian, J.; Filella, X.; Fabregat, A.; Luquin, M.; Hurtado, H.H.; García Humanes, A.; Morales-Ruiz, M.; Fernández-Galán, E. Comparison of Two Automated Immunoassays for Quantifying ProGRP, SCC and HE4 in Serum: Impact on Diagnostic Accuracy. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2025, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Lu, R.; Hu, H.; Guo, L. Application of Serum Markers in Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine 2021, 55, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanella, L.; Fontana, M.; Keller, F.; Campenni’, A.; Ceriani, L.; Paone, G. Circulating Pro-Gastrin Releasing Peptide (ProGRP) in Patients with Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Clin Chem Lab Med 2021, 59, 1569–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhu, J.; Cai, M.; Dai, Z.; Fang, L.; Chen, H.; Yu, L.; Lin, Y.; Lin, E.; Wu, G. ProGRP as a Novel Biomarker for the Differential Diagnosis of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma in Patients with Thyroid Nodules. Endocrine Practice 2020, 26, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Robert, M.; Orois, A.; Augé, J.M.; Halperin, I.; Filella, X.; Molina, R. Utility of ProGRP as a Tumor Marker in the Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017, 55, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsetnes, S.B.; Broughton, M.N.; Paus, E.; Halvorsen, T.G.; Reubsaet, L. Determining ProGRP and Isoforms in Lung and Thyroid Cancer Patient Samples: Comparing an MS Method with a Routine Clinical Immunoassay. Anal Bioanal Chem 2014, 406, 2733–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Q.; Lv, X.; Luo, L.; Zhang, J.; Cai, B. Exploring the Application Value of Pro-Gastrin-Releasing Peptide in the Clinical Diagnosis and Surgical Treatment of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 19576–19582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, F.A.; Batista, M.; Augusto, S.L.; Rita, E.A.; Couto, J.; G, M.R.; Santos, J.; Martins, T.; Cunha, N.; Rodrigues, F. The Role of Procalcitonin and ProGRP in the Follow-up of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Endocrine Abstracts 2025, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonebaum, L.; van, B.M.; Edward, V.W.; van den, B.S.; Peeters, R. PRO-Gastrin-Releasing Peptide as an Additional Screening Marker in the Diagnostic Work up for Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Endocrine Abstracts 2023, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, R.; Kendler, D.B.; Andrade, F.; Nava, C.; Bulzico, D.; Cordeiro De Noronha Pessoa, C.; Corbo, R.; Vaisman, F. CA19-9 as a Predictor of Worse Clinical Outcome in Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Eur Thyroid J 2019, 8, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codrich, M.; Biasotto, A.; D’Aurizio, F. Circulating Biomarkers of Thyroid Cancer: An Appraisal. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisei, R.; Lorusso, L.; Romei, C.; Bottici, V.; Mazzeo, S.; Giani, C.; Fiore, E.; Torregrossa, L.; Insilla, A.C.; Basolo, F.; et al. Medullary Thyroid Cancer Secreting Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9 (Ca 19-9): A Fatal Case Report. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, 3550–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, L.; Romei, C.; Piaggi, P.; Fustini, C.; Molinaro, E.; Agate, L.; Bottici, V.; Viola, D.; Pellegrini, G.; Elisei, R. Ca19.9 Positivity and Doubling Time Are Prognostic Factors of Mortality in Patients with Advanced Medullary Thyroid Cancer with No Evidence of Structural Disease Progression According to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. Thyroid 2021, 31, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimboli, P.; D’Aurizio, F.; Tozzoli, R.; Giovanella, L. Measurement of Thyroglobulin, Calcitonin, and PTH in FNA Washout Fluids. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017, 55, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boi, F.; Maurelli, I.; Pinna, G.; Atzeni, F.; Piga, M.; Lai, M.L.; Mariotti, S. Calcitonin Measurement in Wash-out Fluid from Fine Needle Aspiration of Neck Masses in Patients with Primary and Metastatic Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2007, 92, 2115–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, T.; Miyauchi, A.; Ito, Y.; Takamura, Y.; Amino, N.; Hirokawa, M. Diagnosis of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma by Calcitonin Measurement in Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy Specimens. Thyroid 2007, 17, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diazzi, C.; Madeo, B.; Taliani, E.; Zirilli, L.; Romano, S.; Granata, A.R.M.; De Santis, M.C.; Simoni, M.; Cioni, K.; Carani, C.; et al. The Diagnostic Value of Calcitonin Measurement in Wash-out Fluid from Fine-Needle Aspiration of Thyroid Nodules in the Diagnosis of Medullary Thyroid Cancer. Endocrine Practice 2013, 19, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimboli, P.; Cremonini, N.; Ceriani, L.; Saggiorato, E.; Guidobaldi, L.; Romanelli, F.; Ventura, C.; Laurenti, O.; Messuti, I.; Solaroli, E.; et al. Calcitonin Measurement in Aspiration Needle Washout Fluids Has Higher Sensitivity than Cytology in Detecting Medullary Thyroid Cancer: A Retrospective Multicentre Study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014, 80, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Crea, C.; Raffaelli, M.; Maccora, D.; Carrozza, C.; Canu, G.; Fadda, G.; Bellantone, R.; Lombardi, C.P. Calcitonin Measurement in Fine-Needle Aspirate Washouts vs. Cytologic Examination for Diagnosis of Primary or Metastatic Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica 2014, 34, 399. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanella, L.; Ceriani, L.; Bongiovanni, M. Calcitonin Measurement on Fine Needle Washouts: Preanalytical Issues and Normal Reference Values. Diagn Cytopathol 2013, 41, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimboli, P.; D’Aurizio, F.; Tozzoli, R.; Giovanella, L. Measurement of Thyroglobulin, Calcitonin, and PTH in FNA Washout Fluids. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017, 55, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.W.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Lee, S.G. Concordance of Three Automated Procalcitonin Immunoassays at Medical Decision Points. Ann Lab Med 2021, 41, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, H.H.; Bœuf, A.; Pfannkuche, J.; Schuetz, P.; Thelen, M.; Nordin, G.; Van Der Hagen, E.; Kaiser, P.; Kesseler, D.; Badrick, T.; et al. Harmonization Status of Procalcitonin Measurements: What Do Comparison Studies and EQA Schemes Tell Us? Clin Chem Lab Med 2021, 59, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partyka, K.; Maupin, K.A.; Brand, R.E.; Haab, B.B. Diverse Monoclonal Antibodies against the CA 19-9 Antigen Show Variation in Binding Specificity with Consequences for Clinical Interpretation. Proteomics 2012, 12, 2212–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremser, M.; Weiss, N.; Kaufmann-Stoeck, A.; Vierbaum, L.; Schmitz, A.; Schellenberg, I.; Holdenrieder, S. Longitudinal Evaluation of External Quality Assessment Results for CA 15-3, CA 19-9, and CA 125. Front Mol Biosci 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handling, Transport, Processing and Storage of Blood Specimens for Routine Laboratory Examinations. 2023, 84.

- Fu, W.; Yue, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, S.; Shi, J.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, R. Comparable Analysis of Six Immunoassays for Carcinoembryonic Antigen Detection. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtalewicz, N.; Vierbaum, L.; Kaufmann, A.; Schellenberg, I.; Holdenrieder, S. Longitudinal Evaluation of AFP and CEA External Proficiency Testing Reveals Need for Method Harmonization. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La’ulu, S.L.; Roberts, W.L. Performance Characteristics of Five Automated CA 19-9 Assays. Am J Clin Pathol 2007, 127, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; Davis, T.E.; Diana, T.; Feldkamp, J.; Karger, S.; König, J.; Lupo, M.A.; Raue, F.; Ringel, M.D.; et al. United States and European Multicenter Prospective Study for the Analytical Performance and Clinical Validation of a Novel Sensitive Fully Automated Immunoassay for Calcitonin. Clin Chem 2017, 63, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiriakopoulos, A.; Giannakis, P.; Menenakos, E. Calcitonin: Current Concepts and Differential Diagnosis. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korse, C.M.; Holdenrieder, S.; Zhi, X. yi; Zhang, X.; Qiu, L.; Geistanger, A.; Lisy, M.R.; Wehnl, B.; van den Broek, D.; Escudero, J.M.; et al. Multicenter Evaluation of a New Progastrin-Releasing Peptide (ProGRP) Immunoassay across Europe and China. Clinica Chimica Acta 2015, 438, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).