1. Introduction

In essence, archaeological remains through the friction of time will slowly experience degradation of authenticity, whether it is caused by natural factors or human factors [

1]. So that preservation measures are needed to maintain the values of a number of relics to be maintained and slow down the damage. In particular, rock drawings are very susceptible to natural vegetation disturbance, chemical weathering and vandalism activities. Not a few cases of vandalism were found in prehistoric caves that caused rock paintings to experience a reduction in aesthetic value and authenticity. This can be influenced by ignorance about the ethics of preserving this cultural heritage so that it becomes a problem that must be resolved. Threats to cave wall paintings can come from anywhere, both from natural factors and from human intervention [

2]. These disturbances can be caused by human activities such as agricultural, industrial, residential, and tourism needs [

3]. This condition is reinforced by the many cases of prehistoric sites that are currently experiencing damage dua to their existence in the open and are flueced by climatic and weather conditions which cause rock paintings to experience peeling and even weathering [

4].

[

5] Mentions the aspects of vandalism, namely (a) (graffiti), which includes graffiti, chairs, classroom walls, site boundary walls, or any other public facilities; (b) (cutting), which includes cutting tree branches in the cultural heritage site area without a definite purpose; (c) (taking) this activity includes taking/stealing archaeological findings and cultural heritage objects without asking permission and not returning them and selling the findings for personal economic interests; (d) plucking; (e) destroying. Humans are one of the factors that can cause damage to Cultural Heritage Sites. Vandalism that occurs in caves is generally caused by various factors, such as lack of awareness of visitors, lack of supervision, and weak regulations against this act of destruction. Some visitors consider that leaving marks or carvings on cave walls is part of the tourist experience, without realizing the impact on the sustainability of the site [

6]. In addition, actions that include vandalism in damage to cultural heritage are scribbling on the surface of cultural heritage walls, excavation, stickers, destruction and environmental pollution [

7].

The results of research conducted by [

8] entitled “Vandalism in Prehistoric Caves in Maros Regency” showed that of the 57 caves used as research locations there were 37 caves where there were acts of vandalism and only 15 caves where there were no acts of vandalism. Caves that have a physical form of protection do not guarantee the absence of vandalism, therefore there are several things that become recommendations, namely optimizing socialization to the public and visitors about the important value of the site, optimizing the form of protection and performance of the caretaker.

Research entitled “Study of the Preservation of Prehistoric Cave Paintings in the Maros Pangkep Karst Area of South Sulawesi” said that the number of caves that became the object of study was 44 caves with details of 24 caves in Maros and 20 caves in Pangkep. Based on the results of research that has been done, the level of maintenance of cave paintings in the Maros Pangkep karst area varies from moderate to severe, and only five caves have good cave painting maintenance conditions. This refers to the level of damage and physical weathering (cracking, breaking, wear), biological weathering (growth of algae, moss, lichen), chemical weathering (salting, cementation), which is also influenced by natural and human factors. Therefore, to maintain the level of preservation of prehistoric cave paintings, a cave conservation system is needed that combines environmental conservation, archaeological conservation and preservation- based archaeological resource management.

According to research conducted by [

9] entitled “Vandalism at the Leang-Leang Maros Archaeological Park Site as an Impact of Human Activity” can be used as the main basis for how important it is to anticipate acts of vandalism in prehistoric cave areas. The Leang-Leang Archaeological Park site object is one of the popular tourist destinations in South Sulawesi Province. There are two prehistoric cave sites located in the Leang-Leang Prehistoric Park, namely the Pettae Cave/Leang Site and the Petta Kere Cave/Leang Site. The utilization of the Leang-Leang Antiquity Park site as a tourist destination is a challenge for the preservation of the cultural heritage in it. The results showed that the Leang-Leang Antiquity Park became the target of vandalism from groups or individuals who visited this site object. The forms of vandalism found vary, including graffiti using stationery on karst walls and graffiti using other objects carried out directly on prehistoric paintings.

According to [

10] in his research entitled “The Impact of the Utilization of the Sumpang Bita Antiquities Park as a Cultural Tourism Object in Pangkep Regency” revealed that the development of ancient sites into cultural tourism objects can have a significant impact on the surrounding environmental conditions and the archaeological integrity of the site. This study highlights the importance of sustainable management and a preservation-based approach to maintain the authenticity and long-term sustainability of the site. The study found that increased tourist visitation can increase public awareness of historical and cultural values, but also presents challenges in maintaining the security and physical integrity of the site from acts of vandalism.

In this regard, this problem is considered very serious by all circles, especially in the academic community. The problem that is said to be an act of vandalism that is generally often found in almost all archaeological sites, especially in the prehistoric site area of the Liang Kabori Site, certainly requires a more serious solution as well. This vandalism not only damages artifacts and paintings that have existed for thousands of years, but also reduces the priceless historical and cultural value. This irresponsible act resulted in the loss of important information that could have been further studied by the entire community, especially for archaeologists and historians and other scientists. In addition, the restoration efforts required to repair damage caused by vandalism are often very costly and do not always succeed in returning an artifact or site to its original condition. Therefore, there is a need for awareness and cooperation from all levels of society to protect and preserve these archaeological sites in order to maintain a valuable cultural heritage for future generations.

Vandalism is a behavior that is not commendable with various backgrounds of the actions taken. Generally, acts of vandalism are often found in various places that are public facilities such as building walls, roadsides, under bridges or flyovers, bus stops and several other public facilities. But in this context, the findings of acts of vandalism are not only in places where public facilities as mentioned earlier are often found, due to the irresponsibility of those who carry out these actions. Rather, also in places that are as facilities and infrastructure for science, namely in the area of prehistoric cave sites, especially those found in the Liang Kabori Site area.

Based on the report of the XIX Region Cultural Preservation Center, which is also responsible for the preservation of the Liang Kabori Area as a cultural heritage. In 2018 there were 38 cave and niche sites that had rock drawings in the Liang Kabori Area (Tang, 2020). Furthermore, based on the results of research conducted by Sope and Mahirta in 2023, it is known that there are 5 additional sites so that in that year the rock image sites in this area were found to be 43 cave / niche sites [

11]. The Liang Kabori prehistoric cave area is a dome-shaped karst area or conical hill. On these karst hills, caves or hollows are often found where there are paintings inside. The placement of images on cave walls, in niches and even on cliffs is the main feature of prehistoric paintings in the Liang Kabori area [

12]. The naming of the Liang Kabori Area collectively represents the entire prehistoric cave complex in the region. Although “Liang Kabori” originally referred to only one cave with many rock paintings, the term now represents the entire site due to the similarity of its archaeological findings, namely prehistoric paintings depicting the lives and cultural symbols of early humans.

The Balai Pelestarian Kebudayaan Wilayah XIX, which is under the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, is responsible for the preservation and management of the Liang Kabori Site in Muna Regency, Southeast Sulawesi. The provision of infrastructure is carried out by related parties, for example by the Regional Government of Muna Regency, which renewed the gazebo building, footpaths and traditional houses. Then by the South Sulawesi Region XIX Cultural Preservation Center which made site information boards, signboards, area gates and public toilets. As a cultural preservation agency, BPK XIX has made various efforts to preserve this site, including documentation, conservation, and education to the community about the importance of preserving cultural heritage. They also work closely with local governments and communities to organize cultural activities aimed at raising awareness of the site's historical value.

However, despite these efforts, the Liang Kabori site still faces threats from vandalism. Some reports mention new graffiti being added on top of prehistoric paintings in the cave, as well as the removal of stalactites used as tombstones by the local community. These acts not only damage the authenticity of the site, but also threaten the sustainability of the cultural heritage. This shows that there are still gaps in the supervision and protection of the site, as well as the need for a more effective approach in involving the community to maintain and preserve this cultural heritage.

The Cultural Preservation Center of Region XIX is expected to review the procedures for visiting local and foreign tourists in terms of monitoring vandalism committed by visitors. Although the Balai Pelestarian Kebudayaan Wilayah XIX is actively responsible for conservation and socialization of cultural preservation, challenges in the field such as the limited number of supervisory personnel, the lack of security facilities, and uneven public awareness, cause a gap for irresponsible acts such as vandalism.

The Liang Kabori site as the object of study in this research is one of the caves that has important values that refer to Law No. 11/2010. However, based on initial observations, there are many signs of vandalism such as graffiti on the cave walls and damage to geological structures due to irresponsible visitors. This condition requires special attention to preserve the site so that it can still be enjoyed by future generations.

Figure 1.

Map of Liang Kabori Cave.

Figure 1.

Map of Liang Kabori Cave.

This research needs to be done to maintain the preservation and cultural heritage of the Liang Kabori Site. Vandalism against rock drawings will very likely occur if no educational steps are taken [

13]. Given the nature of rock drawings is very vulnerable and sensitive to the touch of human hands that can make it lose value and damaged as a cultural heritage. Vandalism activities can be in the form of wall graffiti by visitors, taking stalactites and stalagmites, and environmental pollution that occurs in the cave.

Based on this, this research focuses on the impact of visitor activities on cave damage, especially in the form of vandalism that occurs at Liang Kabori Site. By analyzing visitation patterns, the types of vandalism that occur, and the factors that influence these actions, this research is expected to provide a comprehensive picture of the threats to the sustainability of this cave site. This research aims to identify the forms of vandalism that occur, analyze their impact on cave sustainability, and find solutions to reduce destructive activities at Liang Kabori Site. It is hoped that the results of this study can contribute to cave conservation efforts and serve as a reference for tourism managers in implementing stricter policies for the protection of natural and cultural sites.

Cave conservation requires a comprehensive approach, including education to the community, strict supervision of tourism activities, and the application of stricter regulations against vandalism perpetrators. Restoration efforts for damaged parts of the cave should also be considered so that this site can continue to maintain its authenticity for future generations. In addition to the conservation aspect, this research also aims to provide recommendations to related parties in cave management, such as local governments, tourism managers, and environmental conservation communities. With the right policies in place, it is hoped that vandalism in the cave can be suppressed, so that the sustainability of this cultural heritage site can be guaranteed in the long term. Thus, the cave is not only an attractive tourist attraction, but also remains protected as a valuable natural and cultural heritage.

3.Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview of Liang Kabori Cave

Liang Kabori comes fom the Muna tribal language which means writing cave. This very appropriate because along the walls of the cave there are various paintings lined up neatly.

Figure 2.

Front View of Liang Kabori Cave.

Figure 2.

Front View of Liang Kabori Cave.

Administratively, Liang Kabori Cave is located in Liang Kabori Village, Lohia District, Muna Regency, Southeast Sulawesi. Astronomically, it is located at the coordinates of 04o 53' 56.02“South Latitude and 122o 39' 36.00” East longitude. The mouth of Liang Kabori Cave faces west, with an altitude of 262 meters above sea level, with a cave area of 354.1 m2. Access to the location of the site is quite easy, namely by entering the entrance hall of the Liang Kabori Prehistoric site by walking along an asphalt road for about ± 6 km. This cave is located southeast of Metanduno Cave and is about ± 70 km away.

The existence of caretakers at Liang Kabori Cave has a very important role in preserving the cultural, archaeological and ecological values contained therein. As the vanguard of site preservation, the caretakers are tasked with conducting routine supervision of the physical condition of the cave and all elements contained in it, such as prehistoric wall paintings, rock structures, and the surrounding environment. They are responsible for detecting and reporting any form of damage or potential threat, whether it comes from nature (such as weathering or moisture) or from human activity (such as vandalism, artifact theft, or visitors damaging sensitive areas). In addition to the monitoring aspect, the caretaker also has an educative task, which is to convey information to visitors about the importance of the historical and cultural values of Liang Kabori Cave, as well as providing an understanding of responsible visiting procedures. In practice in the field, stewards often face challenges such as limited resources, lack of work support equipment, and lack of support from authorities or local communities. However, with their local knowledge and proximity to the site, caretakers play a strategic role as guardians of cultural heritage values as well as liaisons between the site and the community and visitors. They also play a role in recording data on the condition of the site on a regular basis, assisting research activities, and supporting preservation programs carried out by related agencies such as the XIX Region Cultural Preservation Center. Thus, the presence of caretakers at Liang Kabori is not only important from the technical side of supervision, but also as a key element in community-based preservation efforts and strengthening public awareness of the importance of cultural heritage.

Based on an interview with one of the caretakers (Darma 2025), it provides a fairly in-depth description of the dynamics of work in the field, as well as the challenges faced in maintaining and managing the historic site. Currently, there are three people officially appointed as caretakers at Liang Kabori Site. However, the reality on the ground shows that only one person actively carries out the role of caretaker, and even doubles as a guide for visitors. The limited number of effective personnel has an impact on the irregularity of visiting patterns and the lack of optimal supervision of the site. (Darma, 2025) states that the surge in the number of visitors, especially during the holiday season or on weekends, is a challenge that is very difficult to face alone. This shows the need for serious attention from related parties, both local governments and cultural preservation agencies, to review the caretaker's work system, recruit additional personnel, and implement a more structured visiting system in order to maintain the sustainability of this historical site.

Liang Kabori Cave has a unique and strategic geographical position because it is located in the middle of a residential neighborhood. Its location, which is not remote and relatively close to the center of community activities, makes it easily accessible to anyone, both by local residents and visitors from outside. Because it is open and not in a strictly guarded area, visitors can come repeatedly without much resistance, whether for tourism, research, or just out of curiosity. The results of an interview with one of the visitors, Tiara Kartika (22 years old), said that the reason she always comes to visit Liang Kabori Cave is because of its calm and inspiring natural beauty. She is also interested in a number of paintings on the walls of the cave which according to her hold stories of the past that not many people know. In addition, Tiara herself said that she has visited Liang Kabori Cave six times.

One of the prime locations for cave tourism is Liang Kabori. The cave has a very dense and varied picture painting that attracts tourists to come visit. In addition, this cave has stunning natural scenery and always holds Muna cultural festivals (Tang, 2020: 37). The reality on the ground is that often visitors around the site who come to visit not for the purpose of destroying, but in the end actually damage the archaeological remains contained in the cave and do not realize the important value of the artifacts or relics in it. Some of them accidentally damage artifacts by touching wall paintings, stepping on fragile parts of the floor, or shining a flashlight directly on the surface of the picture without knowing the long-term impact. On the other hand, there are also visitors who intentionally commit vandalism such as crossing out cave walls with names or symbols, carving rock surfaces, and breaking parts of the cave's stalactites and stalagmites.

The Liang Kabori Cave cultural heritage of Muna Regency is included in the object of archaeological heritage which is very important to protect for its preservation. Currently, the attention of the government to the location of the area is quite large. The central government, in this case represented by the South Sulawesi Region XIX Cultural Preservation Center with its functional duties as a Cultural Heritage Preservation Institution, has made various efforts to protect the cave objects that have been identified. The initial form of protection carried out was to inventory the potential of each cave in the form of data collection, surveys, zoning and even in the last 2018 a master plan for the preservation of the Liang Kabori Area was prepared. The status of Liang Kabori Cave in Muna Regency has been established as a cultural heritage object based on the Decree of the Minister of Culture and Tourism KM.8/PW.007/MKP/03 on March 4, 2003 which established the Muna Prehistoric Cave Complex.

3.2. Forms of Vandalism Thah Occur at Liang Kabori Cave

According to Darma (2025), based on the visit book, there was an unusual spike in the number of visitors at the Liang Kabori Site in January of 2025, where 75 visitors were recorded in one month, surpassing the site's average monthly visit which usually ranges below 30 people per month. This spike not only indicates an increased interest in prehistoric cultural heritage, but is also thought to have been triggered by active promotion by the Region XIX Cultural Preservation Center as well as digital and in- person regional tourism activities since the end of 2024. In addition, the weather that tends to be more friendly and the momentum of the New Year holidays are also factors that encourage people to do cultural tourism. Although the number is not large nationally, this surge is quite significant in the context of historical sites that have limited access and are located in areas that have not fully developed infrastructure. Denser-than-usual visitation activity opens up more opportunities for irresponsible visitors to damage prehistoric rock paintings, either by leaving new graffiti on cave walls or taking natural elements such as stalactites. The high level of activity without adequate supervision increases the chances of damage, especially considering the limited security system at this site.

Based on research that has been conducted at Liang Kabori Cave, the forms of vandalism found reflect the low awareness of visitors to the importance of preserving cultural heritage. One of the most striking forms is the graffiti of names written directly on the cave walls using sharp tools such as stones, pointed wood or metal objects that often hit or are very close to the rock drawings. Mathematically speaking, this number is very small, but the impact of this form of vandalism is huge and has a long-term impact later. All of these forms of vandalism, whether done intentionally or out of ignorance, threaten the preservation of Liang Kabori Cave and point to the need for close supervision and more serious education about the importance of preserving historic sites.

3.3. Forms of Vandalism Thah Occur at Liang Kabori Cave

There is a name scribbled by an irresponsible visitor who wrote her name “Rahma Mayang Sari Ayu”. The graffiti was made using the tip of a sharpened piece of wood or used firewood to scratch the surface of the stone (Darma, 2025). The perpetrator deliberately wrote her name or initials as a form of wanting to leave a trace, without realizing that her actions had damaged one of the historical relics. This kind of graffiti disrupts the authenticity, meaning and scientific value of the cave. As well as weak supervision and lack of education for visitors about how fragile and valuable the rock drawings in Liang Kabori Cave are. In line with the results of a similar study, [

14] that vandalism is not just an individual act such as scrawling or carving names on cave walls, but includes systemic and institutional actions, such as: neglect of site protection and as an act of economic exploitation.

Figure 3.

Vandalism on the cave wall using wood (a); graffiti using charcoal (b).

Figure 3.

Vandalism on the cave wall using wood (a); graffiti using charcoal (b).

3.4. Vandalism Graffity on Cave Rocks

According to La Ode Darma (2025), as the site caretaker, visitors often come not only to see or take pictures but there are also some visitors who come with the intention of doing idle things such as vandalizing the walls and rocks of the cave. As seen in the left and rightside pictures in the form of writing personal names, gang names, and even organization names. The left side of the picture shows visitors using weathered rocks to scratch on the rocks. While the rightside picture shows visitors using charcoal to cross out the cave wall. Vandalism often occurs in groups of teenagers or communities who want to express their existence through graffiti or writing. Peer pressure can also encourage people to participate in this act. In line with the results of research [

15] that vandalism of this kind of destruction is categorized into acts of severe vandalism because it is found on the walls of the cave, visitors who do not know will think that the picture made by modern humans is one of the pictures made by the ancestors who inhabited the cave in the past.

Figure 4.

Scribbling on the rocks in the underground passage of the cave.

Figure 4.

Scribbling on the rocks in the underground passage of the cave.

3.5. Vandalism of Scratches on the Cave Wall

Irresponsible visitors often use wood or sharp objects to scratch human images. In addition to damaging the beauty and aesthetics of the rock drawings, it also damages the authenticity of the drawings. The above vandalism is carried out by visitors who are less aware of the importance of preserving existing cultural heritage, as well as weak supervision and lack of education for visitors about how fragile and valuable these prehistoric images are. Some people commit acts of vandalism such as scribbling on the cave walls to leave traces or signs of their presence. In line with similar research [

16] visitor touch, in this case the act of scratching the cave walls using sharp objects, can change the chemical composition and local humidity.

Figure 5.

Vandalism scratches on rock drawings.

Figure 5.

Vandalism scratches on rock drawings.

3.6. Vandalism of Scratches on the Cave Wall

There is plastic waste discarded by visitors when visiting the Liang Kabori Site, seen aqua bottle waste (see pictures a and b) which is discarded in the cave mouth area and on the cave floor. Plastic waste and aqua pipettes were also seen dumped in the area around the cave rocks (see pictures c and d). This action reflects the lack of environmental awareness of visitors. Always throwing garbage out of place will cause inconvenience to this cultural tourism potential. Trash left in the cave not only damages the natural beauty and aesthetic value of the cave, but also threatens the balance of the cave's micro-ecosystem which is very sensitive to outside contamination. This kind of behavior becomes a form of non-structural vandalism that has a long-term impact on the sustainability of the cave. This is in line with the results of research [

17] that human waste, in this case garbage, can damage the aesthetic and scientific value of caves.

Figure 6.

(a and b) plastic bottle waste; (c) dropper; (d) plastic waste and aqua bottles.

Figure 6.

(a and b) plastic bottle waste; (c) dropper; (d) plastic waste and aqua bottles.

3.7. Vandalism of Cutting Stalactites and Stalagmites in the Caves

Local people around the cave area sometimes cut stalactites and stalagmites in the cave for economic purposes, such as being used as basic material for making gravestones. According to Darma (2025) This cutting is usually done traditionally and manually, using simple tools such as chisels, hammers, crowbars, or sometimes with the help of rock saws. They enter the cave and choose a rock formation that looks large, sturdy, and easy to reach, then cut it from the base or center. This action causes permanent damage to the cave's stalactite and stalagmite formations. In line with the results of the study [

18] that vandalism is considered a serious and recurring threat to cave systems and the species that depend on them.

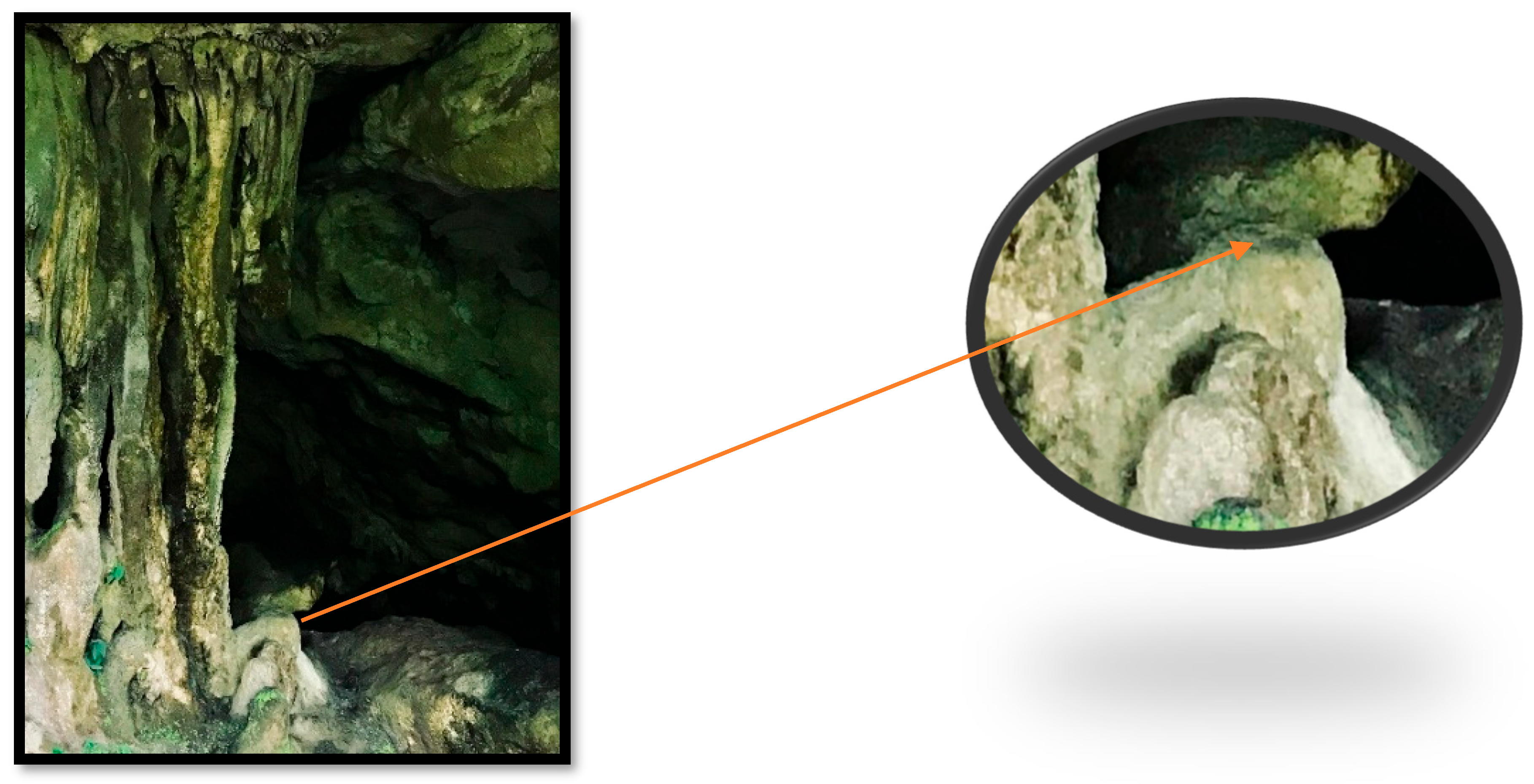

Figure 7.

Cutting marks of stalactites and stalagmites at Liang Kabori Site.

Figure 7.

Cutting marks of stalactites and stalagmites at Liang Kabori Site.

3.8. Vandalism of Cutting Stalactites and Stalagmites in the Caves

The people in Liang Kabori Village take stalactites and stalagmites from the cave usually in the most prominent, striking parts, or have large sizes and aesthetic shapes that are considered suitable for tombstone materials. Stalactites are taken from the ceiling of the cave, while stalagmites are taken from the floor of the cave, where they grow slowly due to water sediment dripping from above. The most commonly targeted parts are the center to the ends of stalactites that have a tapered shape or that look symmetrical and solid. Similarly, stalagmites that are sturdy, thick, and stand with a large diameter are the main targets because they are easier to shape into a whole and strong tombstone board. The activities of the community around the site are also based on a lack of understanding or knowledge about the content and importance of a site. In addition, the removal of stalactites is often done without permission, illegally, or with disregard for conservation rules, thus accelerating the degradation of the fragile karst environment. The Liang Kabori site is in a poor location with very limited supervision. The lack of a caretaker or security system facilitates the taking of artifacts. The main factor causing this vandalism is economic. In line with research [

19] mentioning that in caves such as Actun Tunichil Muknal (Belize) and Naj Tunich (Guatemala), the ancient Maya population erected stalagmites as megaliths/altars/pillars as containers for burials in ritual consecration ceremonies.

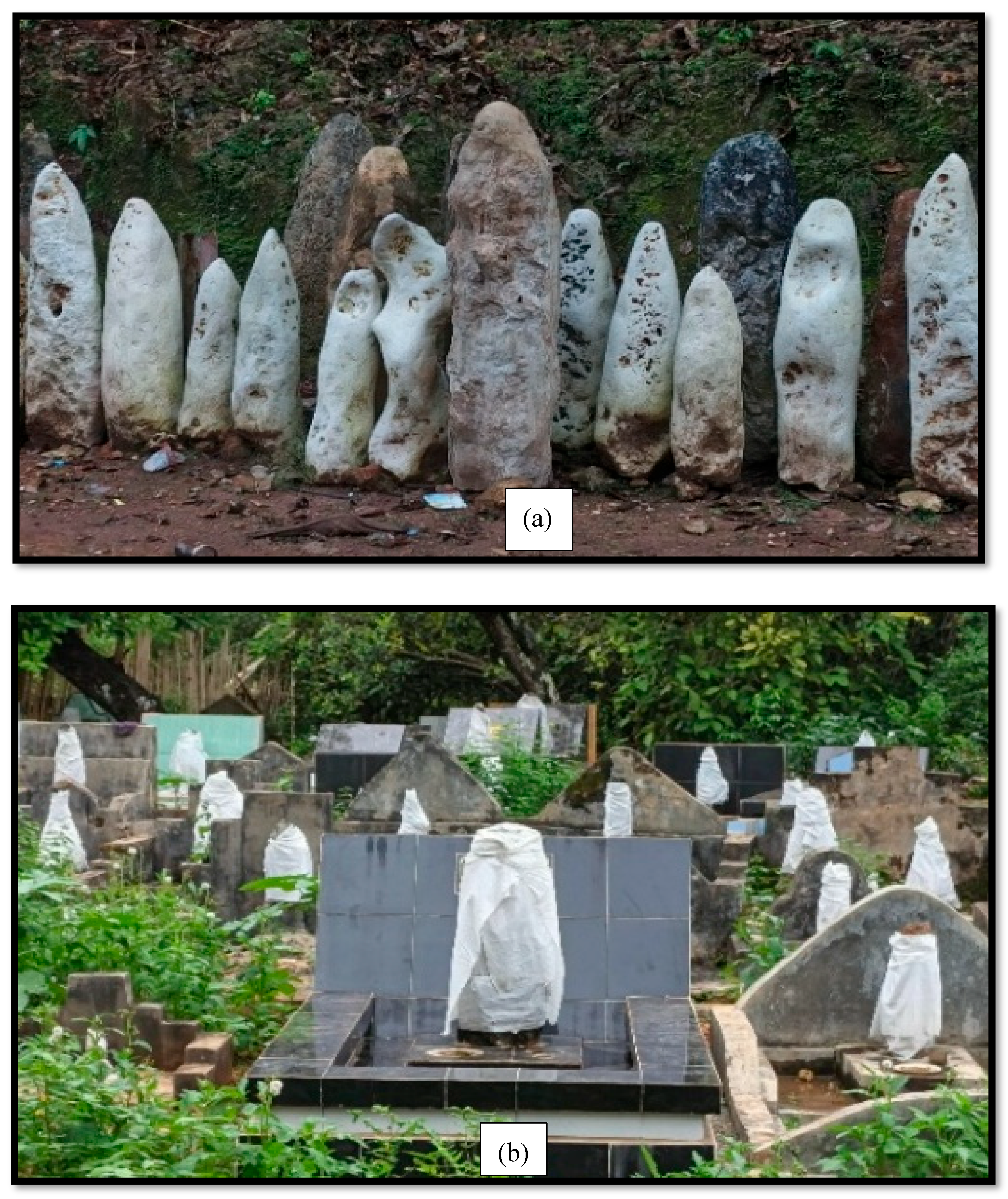

Figure 8.

(a) cave stalactite and stalagmite ornaments; (b) stalactites and stalagmites used as gravestones in burials in Liang Kabori Village.

Figure 8.

(a) cave stalactite and stalagmite ornaments; (b) stalactites and stalagmites used as gravestones in burials in Liang Kabori Village.

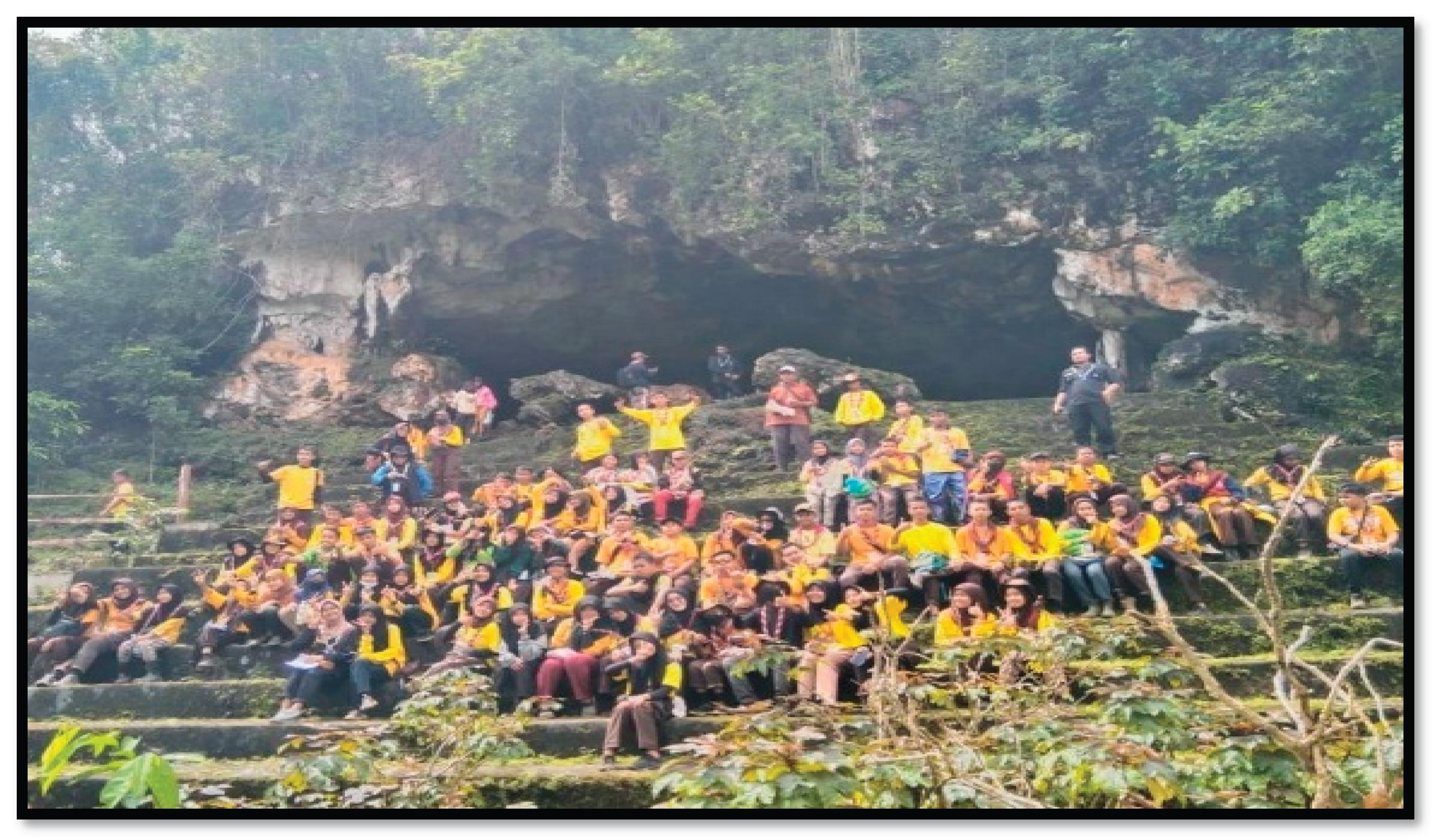

3.9. Surges in the Number of Visitors That Increase the Risk of Site Damage

Visitors who are in front of the cave mouth area and come from other institutions, such as government agencies, educational institutions, environmental communities, or private companies, often have a variety of visiting backgrounds ranging from research purposes, documentation, field studies, to simply educational tourism visits. They usually come in small to large groups, wearing official attributes or agency uniforms, and carrying equipment such as cameras, notebooks, or observation equipment. Under these conditions, visitors who come in large numbers, either individually or in groups, are difficult to monitor thoroughly (Darma, 2025). In line with similar research [

20]. that occurred in Lascaux Cave, the massive human presence caused biological damage and disturbed microclimate conditions in the cave.

Figure 9.

Some visitors to Liang Kabori.

Figure 9.

Some visitors to Liang Kabori.

When visitation increases suddenly, especially during holidays or after tourism promotion activities, supervision becomes disproportionate to the volume of visitors, creating a large gap for vandalism or other irresponsible behavior. The number of caretakers is not proportional to the area and complexity of the site being guarded, causing supervision of the Liang Kabori Site area to be suboptimal. The limited presence of caretakers also hampers efforts to educate visitors directly about the importance of preserving the site as a cultural heritage. This situation emphasizes the need for a stricter and more sustainable visitor management system, such as limiting the number of visitors, installing monitoring cameras, and increasing the participation of local communities as partners in preserving the site.