1. Introduction

Agroforestry is a land use system that incorporates the combination of woody perennial plants, agricultural crops, and livestock to foster beneficial ecological and economic interactions for the production of food, fiber, and livestock. Furthermore, agroforestry is defined by the direct integration of trees and crops on the same land, either spatially or temporally, as outlined by Nair (1985). In contrast, an alternative method involves a “coarse-level mixing” of trees and crops across separate parcels (Price, 1995) or within designated “compartments” (Odum, 1969) on a farm, which is referred to as a “farm mosaic” or mixed farming. A well-managed agroforestry system offers numerous advantages and enhances livelihoods and income generation. Furthermore, agroforestry systems are tailored to specific areas and climates; therefore, it is essential to develop agroforestry systems that are relevant to local conditions and take into account the biophysical and socio-economic contexts on an individual basis. South Africa is recognized as a semi-arid nation that is susceptible to water stress, especially drought.

Furthermore, agroforestry significantly contributes to improving food security by providing a diverse range of products and benefits to farmers. These benefits include food, fodder, and shade for livestock, in addition to timber and renewable wood energy. It boosts agricultural productivity by fostering soil conservation, enhancing soil water retention, increasing soil organic matter, improving soil fertility, and delivering various ecosystem services. This land use strategy holds substantial potential for mitigating climate change through carbon sequestration. Agroforestry systems should also comply with the 4 I’s (Integration, Intention, Interconnected & Intensive) and the 4 F’s (Firewood, Fertiliser, Food & Fodder).

This research reiterates that farmer and community perceptions are defined as the subjective preferences of farmers, which are essential traits that can influence decision-making processes Adesina and Baidu-Forson (1995). These perceptions are shaped by a range of previous behaviour’s, experiences, and observations, along with future aspirations. Additionally, they are affected by various external factors, such as individual and household characteristics, institutions, socioeconomic conditions, and environmental factors (Jha, Kaechele and Sieber, 2019). Over time, farmers’ and community perceptions may evolve as new information emerges and previous perceptions are adjusted (Meijer, Catacutan, Ajayi, Sileshi, and Nieuwenhuis, 2019). It is important to note that farmer/community impressions may not necessarily align with actual reality. Consequently, to prevent biased outcomes, the study considers all farmer/ community impressions, regardless of whether they accurately reflect reality or not.

Furthermore, agri-silviculture represents a system that integrates both crops and trees within the same landscape. As noted by Bentrup et al. (2019) and Maponya et al. (2022), the primary benefits of the agri-silviculture system include: (1) The production of various products such as food, vegetables, fruits, fodder, and forage essential for livestock, as well as fuel wood, timber, and leaf litter for organic manure production. (2) The enhancement and sustainability of crop productivity, which subsequently increases farmers’ income levels. (3) The improvement of the nutritional value of animal feed through the provision of green fodder. (4) The practice serves as an effective method for soil nutrient recycling, thereby reducing the need for chemical fertilizers. (5) The enhancement of farm site ecology by mitigating surface runoff, soil erosion, nutrient loss, gully formation, and landslides. (6) The improvement of the local micro-climate, which boosts the productive capacity of the farm. (7) The alleviation of pressure on community forests and other natural forests for fodder, fuel wood, and timber. (8) The contribution to the beautification of surrounding areas.

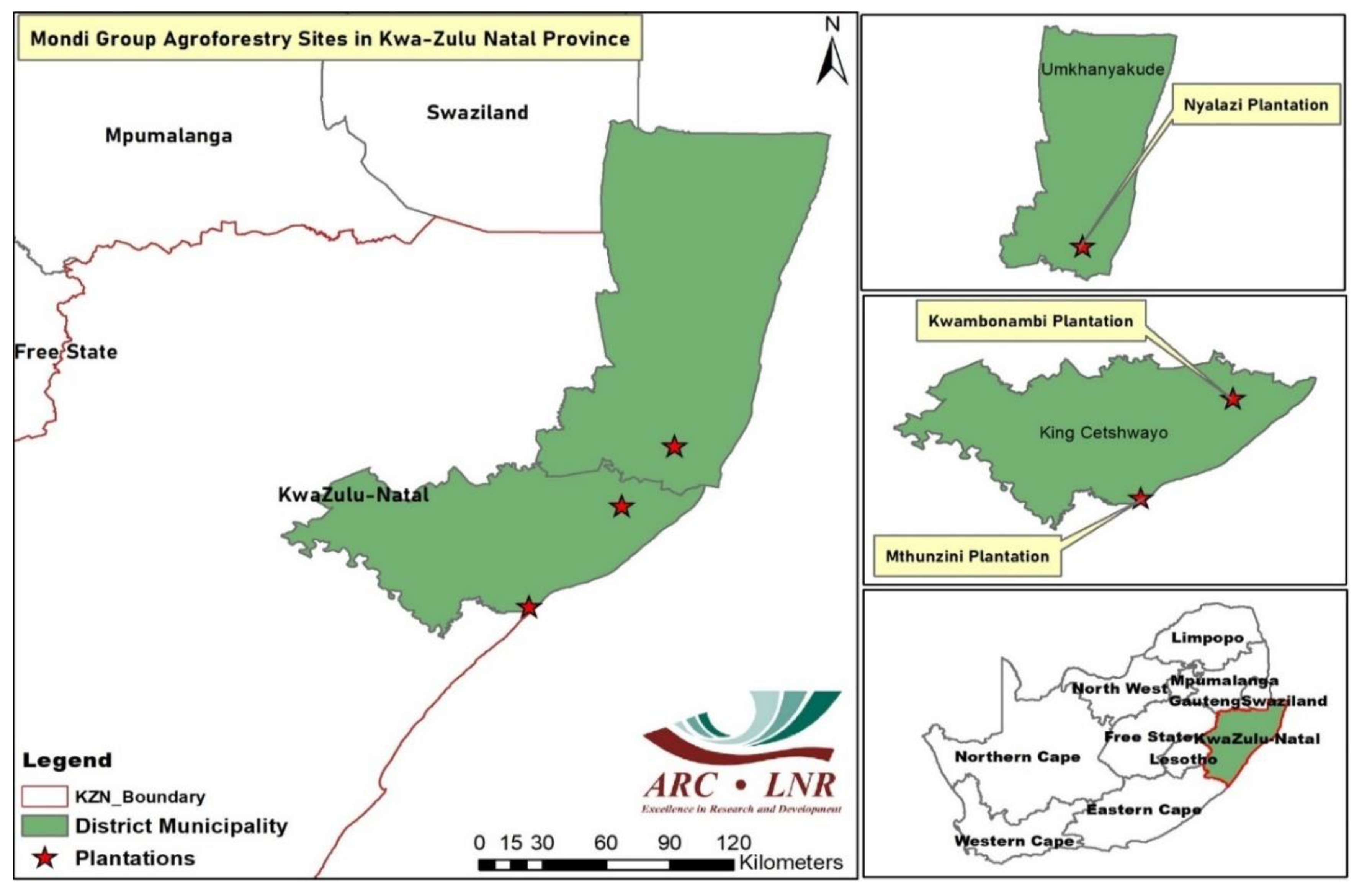

According to ARC (2017), the KwaZulu-Natal Province enjoys a reliable and consistent rainfall pattern, coupled with fertile soils, which have made its agricultural sector notably productive and esteemed for its specialized skills across diverse farming types. KwaZulu-Natal has a total of 6.5 million hectares allocated for agricultural purposes, with 82% of this area being ideal for extensive livestock farming, while the remaining 18% is classified as arable land (KZNDARD, 2020). At the heart of these innovative initiatives is the advancement of agriculture and a commitment to promoting the integrated development of sustainable rural enterprises that can further bolster the province’s agricultural sector. The forestry industry in KwaZulu-Natal covers around 740,000 hectares, representing 8.2% of the province’s overall area. Out of this, 560,000 hectares have been planted, while an additional 190,000 hectares of land, owned by forestry companies, remain unplanted.

In the present study, research was conducted with the overall aim to determine the status of the agri-silviculture practice in terms of socio economic, perceptions and food security. The major objectives were: (1) To identify and describe the socio-economic characteristics of the selected agri-silviculture community growers (2) To determine the perception status of the agri-silviculture community growers

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

A sampled 90 agri-silviculture community growers participated in the study and were spread as follows: The agri-silviculture community growers were spread on the Mondi Group plantation as indicated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Study Design

The research employed both qualitative and quantitative methods concurrently and this was applied with the aim on establishing the limitations, balance and strength of the data. Furthermore, the methods included participatory action research as the community growers and stakeholders benefitted while the research was ongoing. Data collection methods were site observations, past research, web and governmental reports. A closed and open-ended questionnaire with the following sections was used: Socio economic, food security, sustainability, perceptions, market information and observations. Closed-ended questions provide a question immediately and ask participants to choose from a list of possible responses and are quantitative in nature, allowing the researcher to gather numerical data for statistical analysis and it took maximum 20 minutes to interview each community grower. Open-ended questions alternatively are those that provide participants with an allowance to construct their own response about the subject matter. The latter will include focus group discussions and field observations. The Mondi Group team conducted face-to-face interviews with the same 100 community growers were interviewed in their native language for better understanding. The Mondi Group team were presented and trained on the PAR (Participatory Action Research) approach and data collection and analysis.

2.3. Sampling Procedure and Analytical Technique

A purposive sampling technique was used on selected 90 agri-silviculture community growers out of estimated 500 community growers. A rule of thumb was applied, which is the minimum selection of 10% of the population (estimated 500 agri-silviculture community growers) and it is considered as a good sample size. These agri-silviculture community growers were spread on the 300 ha Mondi Group land and each agri-silviculture community grower was allocated an area of land and the sample size was agreed with the stakeholder. The eucalyptus trees were then integrated with Groundnuts.

Data was captured and analysed using the software package for social sciences (SPSS version 20). Descriptive Analysis was used to describe data and Univariate Regression Analysis was conducted to demonstrate the relationship and association of variables. Univariate regression analyses were used to test the association of one explanatory variable at a time with the outcome without worrying about other variables or confounders (unconditional association). This is essential to shortlist variables for multivariable analysis, especially if there are a large number of explanatory variables. It also excluded the variables from further analysis that do not show any significant association with the outcome. Results of univariate logistic regression analyses included Wald, likelihood ratio, chi-square test statistics and P-values, parameter estimates and standard errors, and odds ratios and their confidence limits. For logistic regression, values of parameter estimates are not very intuitive as they are calculated on a log scale.

Therefore, odds ratios are examined, which are calculated after exponentiating parameter estimates. An odds ratio of <1 indicated negative association, whereas values >1 indicated positive association of the tested variable with the outcome.

The following econometric model was used to determine association of variables (Greene, 2003):

Wi is the dependent variable value for person i (2)

Xi is the independent variable value for person i (3)

_ and _ are parameter values (4)

_i is the random error term (5)

The parameter _ is called the intercept or the value of W when X = 0 (6)

The parameter _ is called the slope or the change in W when X increases by one (7)

The assessment tool variables predicted a 90 % (R - squared = 0.90) variation in the dependent variable was explained by the independent variables. Prediction accuracies were assessed based on the coefficient of determination (R - squared). The coefficient of determination R- squared was used to explain the total proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variable. The R- squared removes the influence of the independent variable not accounted for in the constructs. R-squared is always between 0 and 100%. In general, the higher the R-squared, the better the model fits the data.

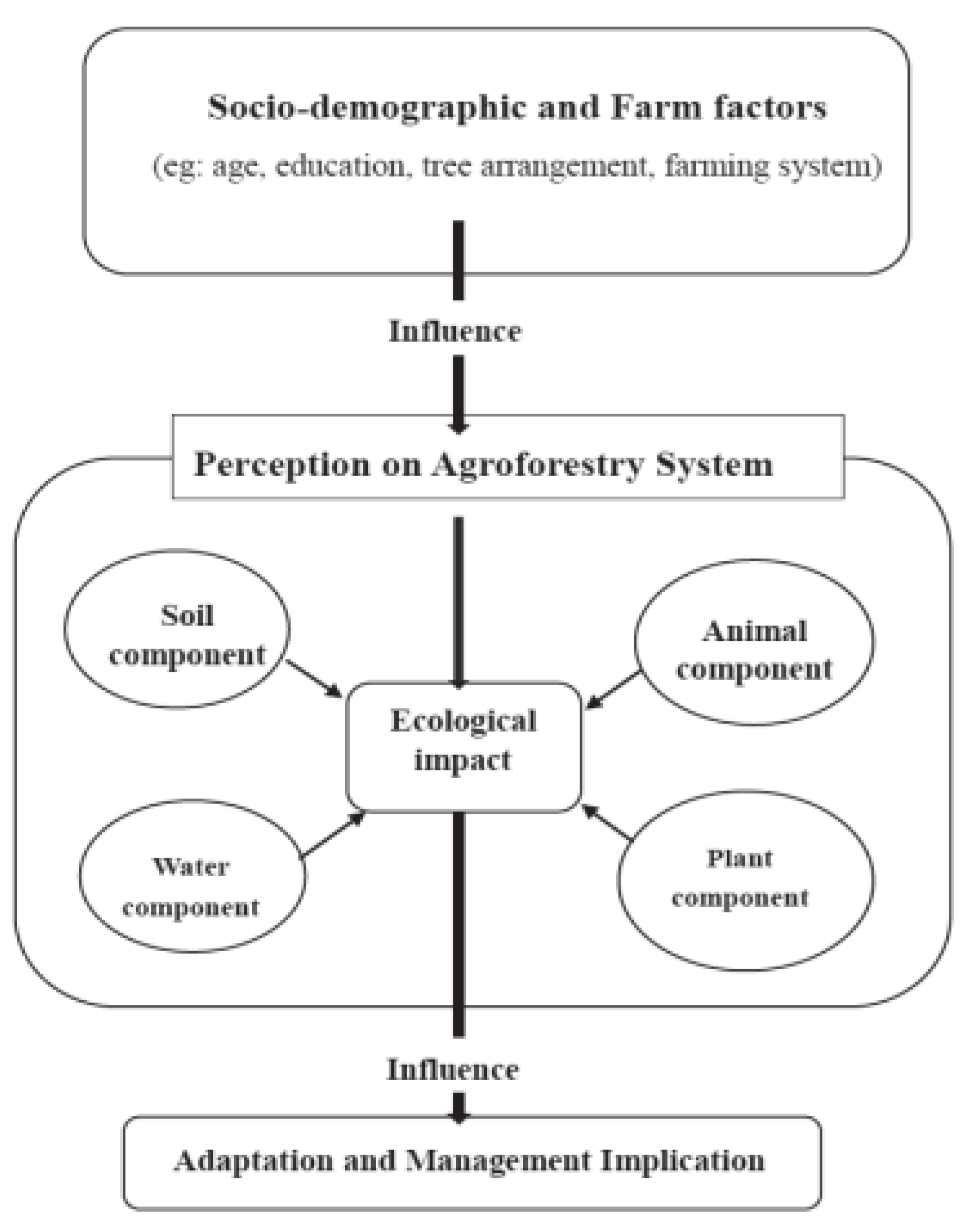

A detailed framework is required to illustrate the interaction of various factors in perception. In our research, we employed an analytical framework that includes both socio-demographic and agricultural factors influencing perceptions regarding the ecological effects of agroforestry (

Figure 2). This framework was developed to demonstrate that farmers’ perceptions of the ecological impacts of agroforestry, categorized under three themes (soil, water, plant, and animal), arise from individual mental processes and are influenced by socio-demographic and agricultural factors. Numerous studies conducted globally have shown that socio-demographic and agricultural factors significantly impact respondents’ perceptions (Sileshi et al. 2008; Sharmin and Rabbi, 2016; Fleming et al. 2019). Consequently, socio-demographic factors such as age, education level, and farming experience, along with agricultural factors like the origin of tree species, the type of agroforestry system, and the arrangement of tree planting, were integrated into the framework.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Agri-Silviculture Community Growers Selected Socio-Economic Characteristics

As shown in

Table 1, the community growers originated from various districts, local municipalities, plantations, and villages throughout KwaZulu Natal Province. The majority of the agri-silviculture community growers interviewed were female. According to

Table 1, 92% of the interviewees were women, while only 8% were men. Regarding educational qualifications (

Table 1), 96% of the growers had education below grade 7, whereas 4% had completed matric. A small percentage (14%) of community growers reported having received training in various aspects of agriculture and forestry, which has led some to engage in vegetable gardening. Furthermore, the community growers stated that they primarily relied on their indigenous knowledge system (IKS) for agroforestry practices. The findings on land acquisition (

Table 1) revealed that the growers were provided land by Mondi Group for agricultural production. The age distribution among the growers indicated that most were over 56 years old (49%). As noted in

Table 1, youth involvement is at 2%, with those aged 36-45 making up 14% and those aged 46-55 accounting for 35%. The farming experience of the agri-silviculture community growers is distributed as follows: 1-5 years (30%), 6-10 years (29%), 11-20 years (21%), and over 21 years (20%).

3.2. Agri-Silviculture Community Growers Perceptions

Perceptions were asked on seven factors namely: (1) Production (2) Demand (3) Related & Supporting Industries (4) Government Support (5) Organizational Strategy, Structure & Rivalry (6) Market and (7) Chance. A 5-point Likert-type scale was used to assess respondents’ attitudes toward various agroforestry practices. Respondents were expected to select one of the options available for each statement/item. The responses of the sample households were then analyzed using percentages because the Likert scale was measured on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree, and 3 not sure).

The results indicated that the following 2/12 production factors (

Table 2) do cause the most decrease in agri-silviculture system competitiveness: cost of production and labour while the following 2/12 do not cause the most decrease in agri-silviculture system competitiveness: lack of knowledge and insufficient source of water. This is true as the community growers indicated that for agroforestry practice, they relied mostly on their indigenous knowledge system (IKS) that is passed from one generation to another. And insufficient water is not a challenge as the plantation area’s high rainfall (+750mm per annum) hence the community growers indicated that they moved to the plantation area due to its good climate.

The results indicated that most of the demand factors (

Table 3) do cause a decrease in agri-silviculture system competitiveness: Among the five demand factors: Distance to market (79%), Market information (64%), Cost to the market (65%) and quality of product (50%). However, 69 % of the community growers disagreed that market for agroforestry do cause decrease in agri-silviculture system competitiveness.

The results indicated that the electricity suppliers (58%) (

Table 4) do not cause decrease in agri-silviculture system while the financial institutions (53%) cause the most decrease in agri-silviculture system competitiveness. The lack of funding/support from financial institutions to purchase production inputs like seeds remains a huge challenge for the community growers.

The results indicated that poor interaction and support between government (59%) & indirect support (52%) (

Table 5) do not cause a decrease in agri-silviculture system competitiveness. Furthermore, among the six government factors: Land reform policy (87%) was perceived as the most important factor causing a decrease in agri-silviculture system competitiveness. This is not surprising as the community growers indicated that they were constrained by the unavailability of land in their villages hence the plantations offered more land for production.

The results indicated that the pricing strategy (53%) (

Table 6) do not cause decrease in agri-silviculture system while most of the communities were not sure. This is consistent with the researchers’ observations because communities’ growers determine their own prices at the informal market. So, they have the freedom to use their own pricing strategies without any interference from the agents etc.

The results indicated that the following market factors (

Table 7) do cause a decrease in agri-silviculture system: Market power of suppliers (69%) and Market power of buyers (69%). Community growers who had some market power over some have created a lot of uncertainties in some agroforestry sites in South Africa. According to Maponya et al. 2022 some community growers tried to use bargaining marketing approach which only benefitted a few. In addition, the power of buyers sometimes resulted in low prices for their groundnuts.

The results indicated that out of 9 chance factors (

Table 8), crime (51%) cause a decrease in agri-silviculture system. Other chance factors like AIDS (44%) and Drought (47%) do also cause significant decrease in agri-silviculture system. In addition, Maponya et al. 2022 emphasised that crime for example poaching is a challenge as the result of lack of fencing and again community growers moved to the plantation area due to its good rainfall as compared to their villages, which are dry.

3.3. Agri-Silviculture Community Growers Socio Economic Factors Affecting Their Perceptions

As shown in

Table 9, there exists a positive significant level among the following variables: age, gender, farming experience, and community perceptions. The estimated values support this observation, as they exceed 1 within the 95% confidence interval. Age did have a significant impact on the community’s grower’s knowledge and perceptions. The agroforestry practice is dominated by older community growers. This situation is concerning and highlights the urgent need to attract the younger generation to agroforestry as a critical priority. However, observations from various provinces in South Africa indicate that youth are more involved in the marketing phase of agroforestry practices rather than in soil preparation and production. A similar trend of youth participation was noted in the Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Eastern Cape, and Western Cape Provinces (Maponya et al. 2022). Recent research carried out in the Indus River Basin of Pakistan and Bangladesh has indicated that younger farmers exhibit a greater interest in adopting agroforestry practices compared to their older counterparts. This trend is attributed to their enhanced understanding of the advantages associated with the implementation of advanced agricultural technologies in agroforestry practices (Mahmood and Zubair, 2020). The agri-silviculture system in KwaZulu Natal is also dominated by women as most men have migrated to the cities in search of work.

Furthermore, while both men and women participate in the management of trees cultivated on farms, existing literature indicates that women predominantly carry out most of the work, particularly during the initial phases of tree establishment. Research conducted by Epahra (2001) in Tanzania and by Gerhardt and Nemarundwe (2006) in Zimbabwe revealed that more than 60% of women in Tanzania are tasked with the management of tree species planted on farms. It is also not surprising that there is a positive significant level between farming experience and community perceptions. The communities expressed that it is through prolonged experience that they can effectively manage their designated plots. Consequently, they predominantly depended on their indigenous knowledge system (IKS) for agroforestry practices rather than formal training. As noted by Jose (2009) and Rao et al. (1997), the years of experience within the communities show a significant and positive correlation in perception studies. Thus, farmers with greater experience have noted improvements in these variables compared to those with less experience.

4. Conclusions and Recommendation

Recognizing and tackling main perceptions and factors that determine the competitiveness of the communities in agri-silviculture practices are relevant to the agroforestry adoption. Perceptions were asked on seven factors namely: (1) Production (2) Demand (3) Related & Supporting Industries (4) Government Support (5) Organizational Strategy, Structure & Rivalry (6) Market and (7) Chance. A 5-point Likert-type scale was used to assess respondents’ attitudes and perception toward various agri-silviculture practice. Most of the communities agreed and had a positive perception of agroforestry practices competitiveness to meet their basic needs in terms of fuel wood, fruits, fodder, timber, vegetables, and so on, as well as accepting that agri-silviculture practice are critical for the community to adopt, thus benefiting the economic, social, and environmental well-being of the community. In conclusion, identified community perceptions are in line with some of the researcher field observations and it is thus recommended that stakeholders should take note of the perceptions identified by the communities and the positive significant levels among the following variables: age, gender, farming experience, and community perceptions to increase agri-silviculture system competitiveness in South Africa.

References

- Adesina, A.A.; Baidu-Forson, J. Farmers’ perceptions and adoption of new agricultural technology: evidence from analysis in Burkina Faso and Guinea, West Africa. Agricultural Economics 1995, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Agricultural Research Council (NRE). (2024). Pretoria, South Africa.

- Ahmad, S.; Zhang, C.; Ekanayake, E.M.B.P. Smallholder Farmers’ Perception on Ecological Impacts of Agroforestry: Evidence from Northern. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Agricultural Research Council ISCW (ARC-ISCW). (2017). Pretoria, South Africa.

- Bentrup G, Patel-Weynand T and Stein S (2019) Assessing the role of agroforestry in adapting to climate change in the United States, 4th World Agroforestry Congress, 20-22 May 2019 Le Corum, Montpellier, France.

- Ephra, E. (2001). Assessment of the role of women in agroforestry systems: a case study of Marangu and Mamba Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. World Agroforestry Centre. Nairobi, Kenya.

- Fleming, A.; O’Grady, A.P.; Mendham, D.; England, J.; Mitchell, P.; Moroni MLyons, A. Understanding the values behind farmer perceptions of trees on farms to increase adoption of agroforestry in Australia. Agron. Sustain. Deve 2019, 39, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt, K.; Nemarundwe, N. Participatory planting and management of indigenous trees: Lessons from Chivi District, Zimbabwe. Agriculture and Human Values 2006, 23, 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W. (2003). Econometric analysis (5th Ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Jha, S.; Kaechele, H.; Sieber, S. Factors in Guencing the adoption of water conservation technologies by smallholder farmer households in Tanzania. Water 2019, 11, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for ecosystem services and environmental benefits: an overview. Agroforest Syst. 2009, 76, 10. [Google Scholar]

- KZNDARD (KwaZulu Natal Department of Agriculture and Rural Development). (2020). Annual-Performance-Plan-2020_21.

- Mahmood M.I and Zubair M. (2020). Farmer’s Perception of and Factors Influencing Agroforestry Practices in the Indus River Basin, Pakistan. Smal-scale. [CrossRef]

- Maponya, P.; Madakadze, I.C.; Mbili, N.; Dube, Z.P.; Nkuna, T.; Makhwedzhana, M.; Tahulela, T.; Mongwaketsi, K.; Isaacs, L. (2022). Flattening the food insecurity curve through agroforestry: A case study of agrosilviculture community growers in Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces, South Africa. In: Microbiome Under Changing Climate Elsevier: ISBN: 978-0-323-90571-8. Chapter 6, pg 143-159.

- Meijer, S.S.; Catacutan, D.O.; Ajayi, C.; Sileshi, G.W.; Nieuwenhuis, M. The role of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions in the uptake of agricultural and agroforestry innovations among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 2015, 13, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, P.K.R. Classification of agroforestry systems. Agroforestry systems 1985, (3), 97–128. [Google Scholar]

- Odum, E. The strategy of ecosystem development. Science 1969, (164), 262–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Price, C. Moderate discount rates and the competitive case for agroforestry. AgroFor. Syst. 1995, 32, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.R.; Nair, P.K.; Ong, C.K. Biophysical interactions in tropical agroforestry systems. Agroforest. Syst 1997, 38, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmin, A.; Rabbi, S.A. Assessment of farmers’ perception of agroforestry practices in Jhenaidah district of Bangladesh. J. Agri. Ecol. Res. Intern 2016, 1, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Sileshi, G.W.; Kuntashula, E.; Matakala, P.; Nkunika, P.O. Farmers’ perceptions of tree mortality, pests and pest management practices in agroforestry in Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia. Agroforest System 2008, 72, 87. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).