1. Introduction

The integration of digital technologies into residential infrastructure is rapidly reshaping how communities interact, manage shared resources, and navigate collective responsibilities. In multi-unit housing systems, such as condominiums, traditional intercom devices have historically served a narrow function—namely, basic access control and communication. However, the convergence of behavioral theory, gamification, and low-cost digital interfaces offers a unique opportunity to reimagine the intercom as a tool for standardizing cooperative behavior and supporting smart, sustainable living environments.

As a matter of fact, we are currently experiencing the many requests arising from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as the decarbonization and the control of energy consumption [

1], or the need of more space for the living in cities are overcrowded and not to a human scale, let apart the need for the incorporation of cutting-edge technologies for creating safe and sustainable environments [

2]. Also, there is a growing interest in Artificial Intelligence (AI) automation and the Internet of Things (IoT) in the living environments, to modulate more ethical decision-making, to curb economic inequality, and prevent environmental damage [

3]. As developed by Gračanin et al. (2011), the Human Computer Interaction (HCI) has been for years a source of awareness of our living environments, for example, through mobile notification systems [

4]. Then, a sophisticated “computational and communicational infrastructure,”

[3, pag. 165] serves not only to provide a variety of services with the aim of improving the living environment, but also to customize it based on the user experience. Reference [

5] uses the “design for all” method to support both the design of inclusive environments and to improve the user-environment interaction.

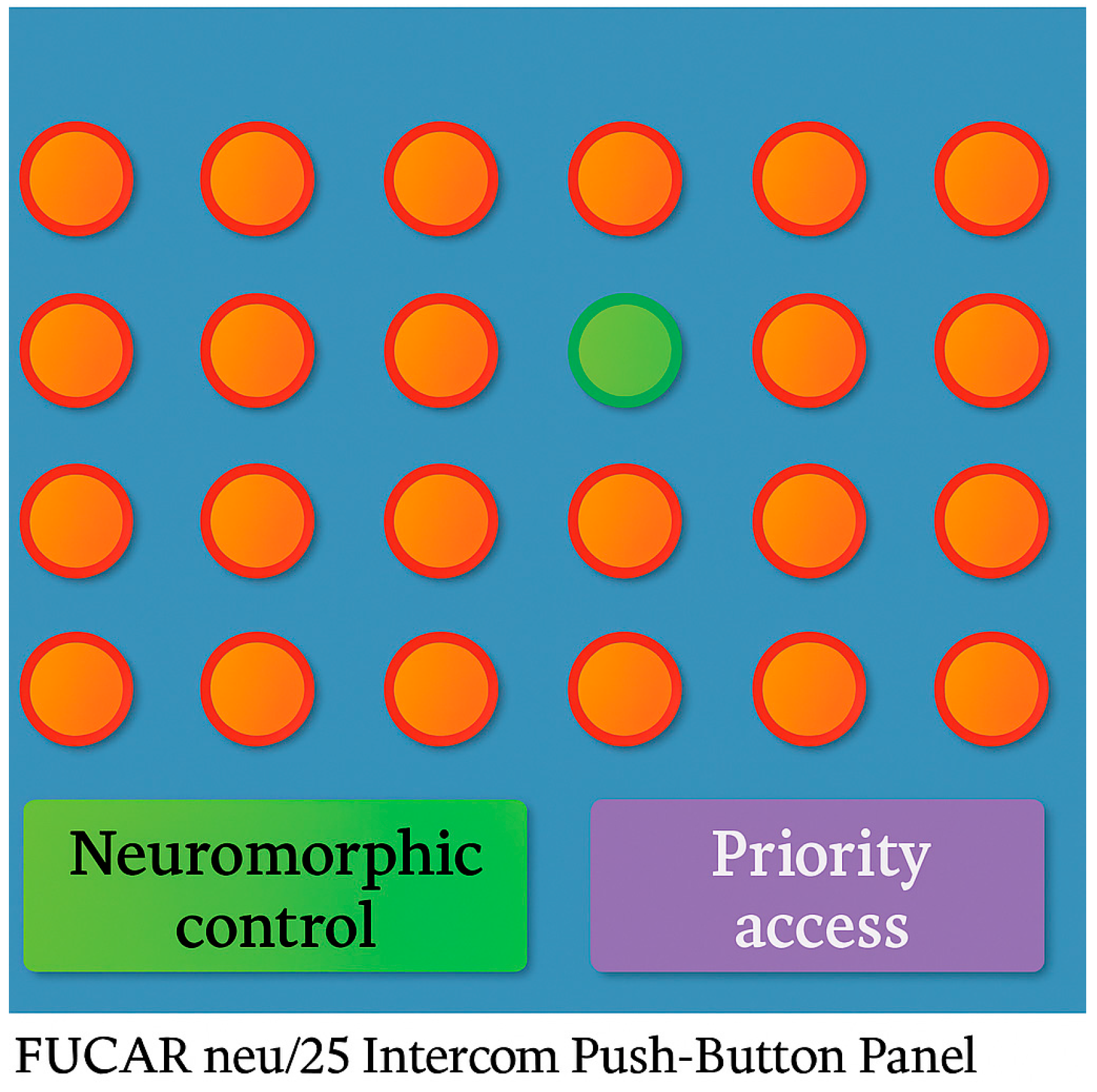

This article introduces a design proposal—the FUCAR neu/25 intercom panel—for a

behaviorally enhanced condominium intercom push-button panel (CIP-BP) that incorporates core principles of

neuromorphic learning and

gamified incentivization. Inspired by John C.H. Watkins’ (1989) work on delayed rewards and Q-learning [

6], the panel enables residents to participate in a transparent feedback system that encourages positive social behavior, such as reducing noise pollution, optimizing common area use, and enhancing mutual trust. The system, piloted in a Sicilian condominium, builds upon

game theory and

bounded rationality models, framing the building as a network of agents engaging in strategic interaction—where outcomes depend on both individual actions and the collective response.

In doing so, the paper contributes to current discussions on

smart infrastructure standardization [

7,

8], proposing the CIP-BP as a replicable model for other urban residential contexts. By embedding decision-making logic into the intercom itself—via features such as remote monitoring, access privileges tied to behavioral scores, or group-level alerts—the project addresses several key goals of

Regional Innovation and International Cooperation in Standards (RIICS), notably:

Green and cooperative behavior via gamified energy-saving protocols

Digital governance aligned with inclusive innovation frameworks

Architectural interoperability of communication and access-control systems

Contribution to SDG 11 through smarter, more participatory building design

The remainder of the paper explores the CIP-BP’s role in promoting social capital, reducing interpersonal conflict, and offering a standards-based platform for urban cooperative resilience.

2. Building Social Capital through Behavioral Interfaces in the Condominium Life

2.1. Cooperative Governance and Community Resilience

The condominium association represents more than a legal body—it functions as an emergent social institution that anchors resilience in the face of social and environmental disruptions. As demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, shared living spaces became critical sites for localized risk response and mutual support. Within this context, the governance structure of the condominium, particularly through the administrator and legal representatives, facilitates not only compliance but also the coordination of cooperative action [

9,

10,

11].

These interactions resemble the

coalition formation dynamics in game theory, where equilibrium arises when no subgroup of agents can unilaterally improve their position. In such settings,

shared governance mechanisms—including committee-based decision-making and socio-juridical precautionary practices—play a central role in fostering inclusive, adaptive responses to uncertainty. The administrator, backed by legal expertise, becomes a broker of collective responsibility, ensuring documentation, transparency, and trust [

12].

Social capital in this context functions as a productive resource—akin to physical or human capital—that enables residents to navigate shared challenges and foster a sense of belonging. Reference [

13] highlights the importance of the neighborhood or community environment in determining well-being, emphasizing that poor community environments are linked to various negative health outcomes. This is highly relevant to condominium living, where the quality of the residential environment can significantly impact residents’ well-being. Also, the significance of material aspects of the residential environment in enhancing well-being, such as factors as perceived diversity, safety, and aesthetics, is crucial for creating a positive living experience in condominiums [

12]. While all unit owners are members of the association, legal authority is exercised through elected representatives, reinforcing structured participation. Regular contributions, upkeep of common spaces, and joint rule enforcement constitute essential processes through which

behavioral norms are stabilized and trust is regenerated over time [

8,

10,

14].

The condominium studied here spans a demographically diverse population—students, professionals, and retirees—aged between 17 and 91. Its evolving composition, shaped by migration and generational turnover, mirrors broader trends in small urban communities [

15]. Notably, local educational expansion in recent decades has shifted ambition dynamics among younger residents, fostering a different relationship to place, education, and civic engagement [

15]. These demographic transitions influence both

network resilience and

cooperation thresholds within the building ecosystem.

2.2. Action Situations and Behavioral Regularities

In order to understand the structure of collective behavior within the condominium, it can be modeled as a bounded social system composed of repeated ‘action situations.’ Drawing from Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework and Situational Action Theory (SAT), we investigate how decisions emerge from individual positioning, shared rules, and anticipated outcomes. Although SAT originated within criminological theory, focusing on rule-breaking behavior, its core premise—that actions and their propensities are shaped by social context and situational interactions—extends beyond this domain. In our understanding, these interactions are particularly relevant in structured environments, where physical space and social norms jointly guide choices and behavioral patterns [

16].

Hardie and Rose (2025) emphasize that while individual propensity and exposure are significant, situational deterrents—akin to those employed in Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED)—can promote self-regulation and moral behavior, encouraging actors to adhere to community norms [

15]. Similarly, Lefevor and Fowers (2016) have explored the influence of situational factors on spontaneous prosocial behavior, finding that volunteering and other cooperative actions are not solely driven by personality traits but also shaped by exchange dynamics and feedback loops within structured social contexts [

17].

A previous survey conducted within this condominium examined residents’ cooperation patterns and rule adherence during the pre- and post-pandemic periods [

15]. The first survey focused on self-observed variables to understand the household structure, socioeconomic status, and well-being of individuals within the condominium. The variables included Size of the Family (self-observed); Level of Education (self-observed); Professional Status (self-observed); Travel History (self-observed); and Confidence in Sustainability (interviews via mobile chat) especially with the aim to provide insights of condominium residents’ environmental consciousness, which is relevant in discussions about economic and environmental sustainability.

The second survey aimed to delve deeper into additional factors that play a crucial role in shaping the community’s response to uncertainties. These new variables were made to interact with the previously studied ones to provide a holistic understanding of the community’s responses to unexpected events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The new variables included Employment Stability, Technological Adaptability, Social Network Strength, and Community Engagement, among others, with the aim to provide insights into condominium residents’ level of engagement and involvement in community activities, as strong community ties can contribute to resilience facing challenges and uncertainties [

12].

The main outcomes of the study were the result of self-observational tools and self-referencing to the condominium where the first author lives. The study aimed to uncover patterns of resilience and adaptation within the community, contributing to the condominium’s ability to navigate challenges, adapt to uncertainties, and foster a supportive environment.

The findings indicated a high degree of adaptive behavior, legal compliance, and informal resilience mechanisms—ranging from collective purchasing strategies to mutual aid. Internal governance structures were modified to streamline responses to regulatory shifts, budgetary constraints, and safety protocols [

15]. These adaptive strategies highlight how normative alignment and distributed awareness can enhance local capacities for risk management and economic coordination. In

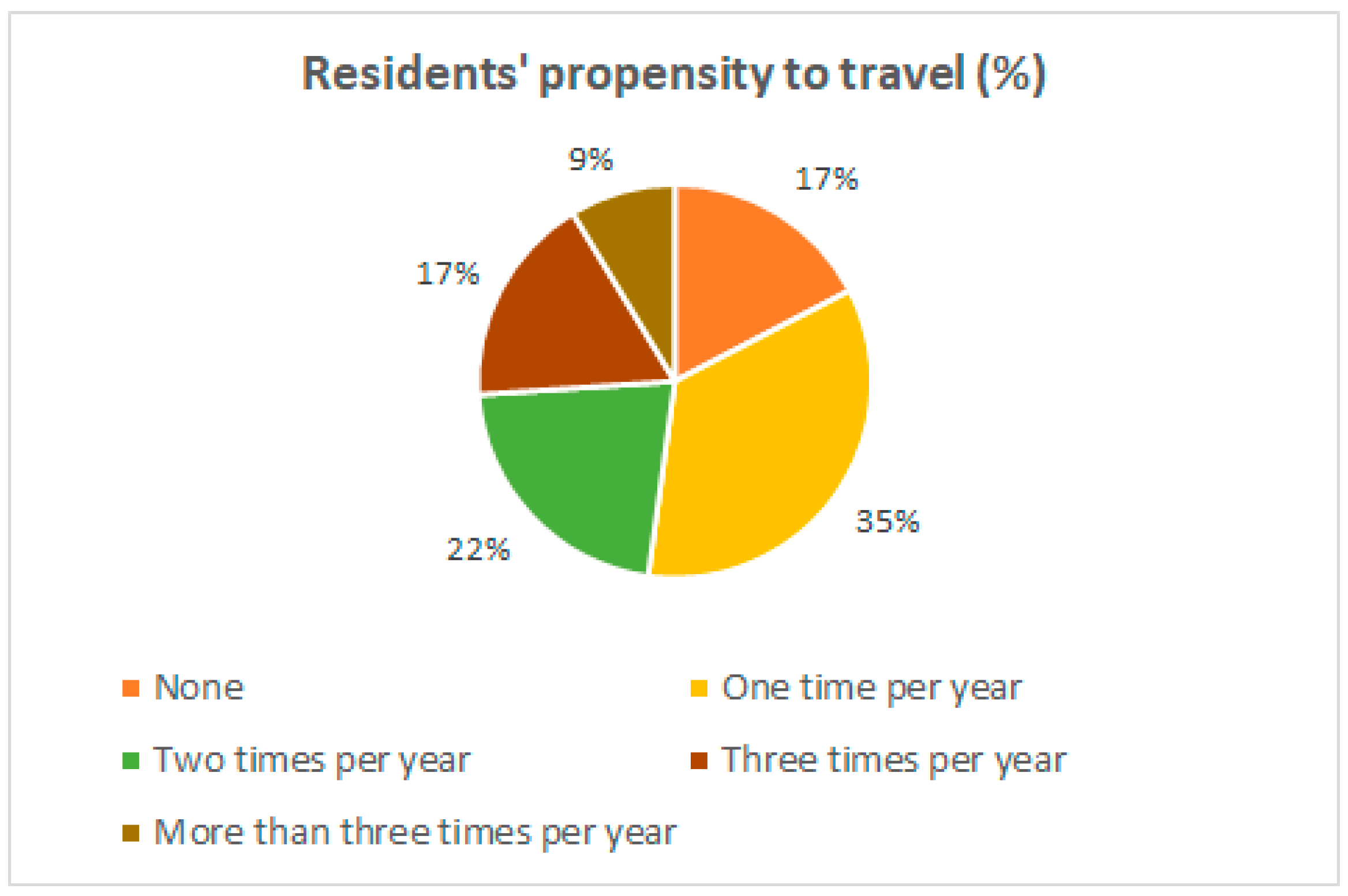

Figure 1, we have an indication of the residents’ propensity to travel as self-observed during the first round of the survey.

The action situation framework isolates key dimensions of decision-making in this context:

Actors: Residents, administrator, legal counsel.

Positions: Legal authority, committee member, individual co-owner.

Permitted actions and outcomes: Voting, non-compliance, escalation.

Control and knowledge: Transparency of rules, access to updates.

Costs and benefits: Maintenance fees, social esteem, sanctions.

These variables are not only theoretical—they are encoded into real-time behavior and institutional routines. Furthermore, they lend themselves to modeling via game-theoretic structures and neuromorphic systems that simulate adaptive strategies over time.

2.2.1. Mechanisms for Cooperative Behavior and Behavioral Design

At the core of this study is the recognition that the ethical and behavioral fabric of the condominium is shaped by three interdependent mechanisms:

Social norms and peer regulation

Collective rationality and outcome weighting

Behavioral efficiency linked to expectations and reward structures

Table 1 below shows the key constructs are used to develop the intercom panel interface.

These mechanisms are supported by both formal structures (e.g., rules, enforcement) and informal channels (e.g., gossip, praise, shame). Shared responsibility plays a critical role here, providing a foundation for cooperation by reducing the perceived risk of individual actions. In such contexts, decisions are not isolated but are embedded in a network of social expectations and mutual dependencies. This encourages broader participation, as individuals act with the understanding that the consequences of their choices are distributed across the community.

2.2.2. Shared Responsibility as a Driver of Cooperative Action

Shared responsibility not only motivates collective decision-making but also protects individuals from the negative consequences of failure. It provides a buffer against risk by distributing potential losses across the group, thus encouraging members to engage in joint actions that might be too costly or risky to undertake alone. This is particularly relevant in condominium settings, where decisions regarding communal resources, maintenance, or governance often involve high complexity and uncertainty, making it difficult to attribute outcomes to a single individual [

18].

For instance, community committees offer ‘soft structures’ for shared governance and ethical learning, where residents can collaboratively address common challenges. This collective approach aligns closely with the principles of 'shared responsibility,' allowing individuals to feel more secure and motivated to invest in the public good. Research by El Zein et al. (2021) suggests that individuals are often more willing to engage in prosocial behavior when they perceive their actions as part of a larger, collective effort. This reduces the psychological burden of regret and perceived personal failure, promoting sustained cooperative behavior [

18], p. 7.

Furthermore, Keshmirian et al. (2023) highlight that shared responsibility can strengthen community bonds by enhancing mutual trust and reducing the perceived risk of exploitation. In practical terms, this means that residents who see themselves as part of a shared endeavor are more likely to participate in maintenance, emergency preparedness, and cost-sharing initiatives, reinforcing the social fabric of the community [

19].

2.2.3. Linking Shared Responsibility to Behavioral Design

The principles of shared responsibility are directly relevant to the design of cooperative technologies like the CIP-BP (Condominium Intercom Panel - Behavioral Panel). The CIP-BP aims to encode these sociological insights into a practical, interactive platform that facilitates coordination, communication, and collective decision-making. As previously mentioned in

Section 1. Introduction, the panel should enable residents to participate in a

transparent feedback system that encourages positive social behavior and shared responsibility, such as reducing noise pollution, optimizing common area use, and enhancing mutual trust. The system builds upon game theory and bounded rationality models, framing the building as a network of agents engaging in strategic interaction, where outcomes depend on both individual actions and the collective response. Its core is represented by the employment of a Q-learning algorithm as first developed by C.H. Watkins [

6]. Q-learning is a model-free reinforcement learning algorithm used to find the optimal action-selection policy for a given Markov decision process (MDP). It learns to make decisions by iteratively updating estimates of the value of

taking a particular action in a particular state.

At its core, the Q-learning algorithm maintains a table of Q-values, where each entry represents the expected cumulative reward for taking a particular action in a particular state and then following the optimal policy thereafter. The algorithm iteratively updates these Q-values based on the rewards received from the environment.

The basic steps of the Q-learning algorithm are as follows:

Initialize Q-table: Initialize the Q-table with arbitrary values, typically zeros.

Choose action: Select an action to take in the current state. This can be done using an exploration strategy (e.g., epsilon-greedy) to balance exploration and exploitation.

Take action and observe reward: Execute the chosen action in the environment and observe the reward received, as well as the next state.

Update Q-value: Update the Q-value of the current state-action pair based on the observed reward and the maximum Q-value of the next state.

Repeat: Repeat steps 2-4 until convergence or a predefined number of iterations.

The Q-learning algorithm converges to the optimal action-selection policy under certain conditions, such as having a finite state and action space and sufficient exploration. It is widely used in various domains, including robotics, game playing, and optimization problems.

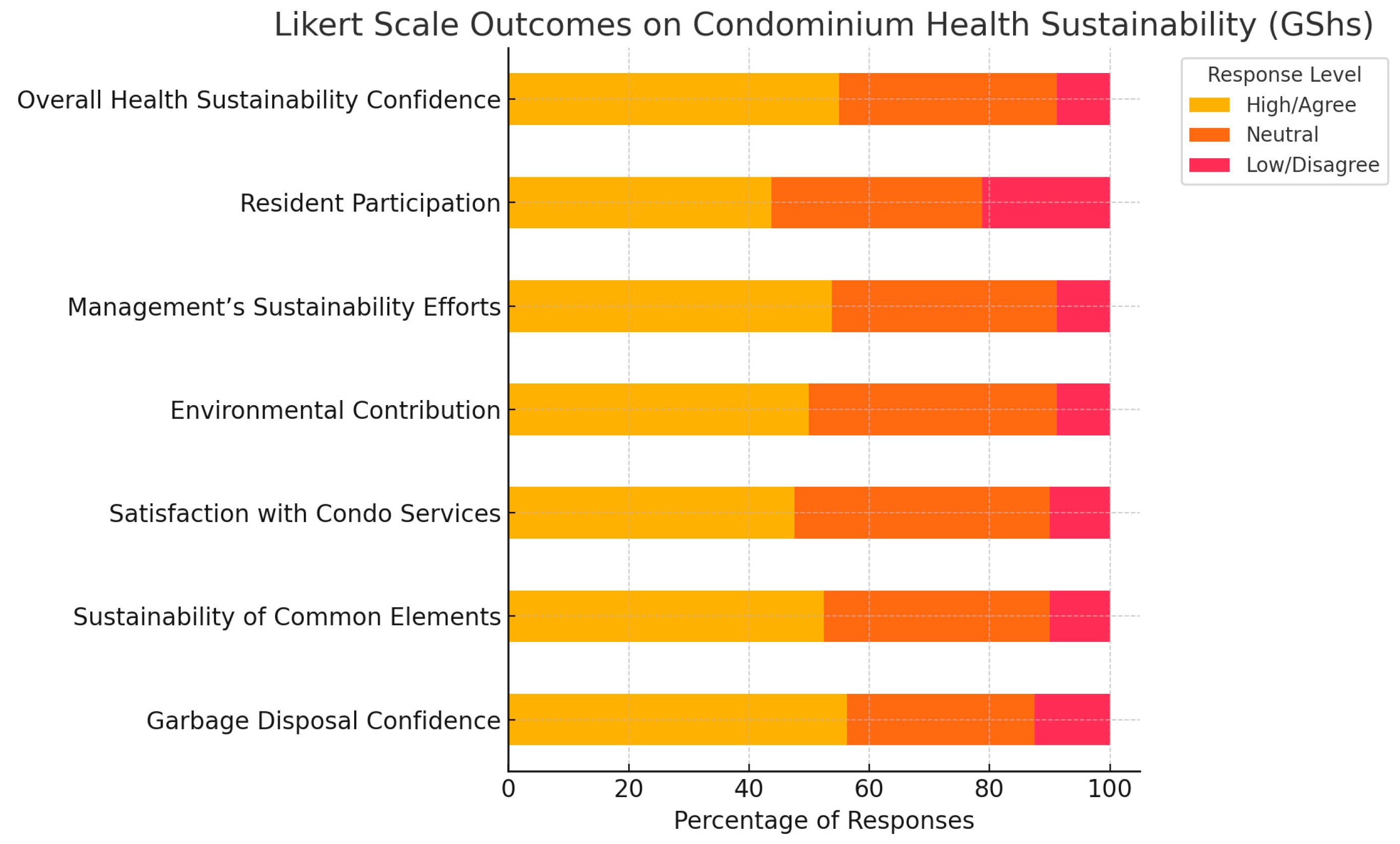

Figure 2 below shows the hypothesized outcomes on the general sustainability/health attitudes we achieved among residents during the second round of surveys in the condominium.

By embedding mechanisms for feedback, peer recognition, and transparency, the CIP-BP helps internalize norms and reinforce cooperative behaviors.

For example, the CIP-BP interface can include features such as:

Positive Feedback Loops: Residents receive symbolic recognition or reduced costs for consistent cooperation (e.g., participation in maintenance or recycling programs).

Transparent Communication Channels: Regular updates on building management decisions, financial reports, and safety protocols.

Mild Deterrents: Minor restrictions or exclusion from shared benefits for repeated non-compliance, reinforcing the boundaries of acceptable conduct without imposing heavy-handed oversight.

This approach resonates with Luhmann’s concept of

“expectation of expectations,” where social systems stabilize not by directly controlling individual behavior, but by structuring what individuals expect from one another [

20]. In this sense, the intercom panel becomes not just a communication tool but a

behavioral interface standard—a micro-infrastructure encoding cooperation protocols into everyday interactions.

3. Advantages and Benefits of Neuromorphic Engineering

Neuromorphic systems are inspired by the brain’s structure and functionality [

21], particularly in how information is processed efficiently, adapted, and optimized in a decentralized and parallel manner [

22]. The connection lies in how the human brain and neuromorphic systems handle bounded rationality, collective behavior, and dynamic decision-making. Neuromorphic engineering is transforming the field of computing by designing

systems that mimic the human brain’s neural structure and functions. This field, rooted in interdisciplinary concepts from biology, physics, mathematics, and electronic engineering, focuses on building artificial neural systems capable of sophisticated and efficient processing [

21,

24].

Neuromorphic computing refers to hardware systems that use artificial neurons for computation, emulating the brain’s ability to process information in real-time using spiking neural networks (SNNs). These systems can be analogic, digital, or mixed-mode, with advanced designs like oxide-based memristors and spintronic memories mimicking synaptic behavior. Compared to traditional digital computers, which rely on binary logic, neuromorphic systems are event-driven, processing information asynchronously and only when needed, thus significantly improving energy efficiency.

Neuromorphic systems are designed to process information more efficiently, using less power than traditional computing methods. These systems are highly adaptive and capable of processing sensory inputs in real-time, making them invaluable in fields like autonomous driving, AI research, and real-time data processing [

25].

As neuromorphic engineering continues to evolve, we can expect innovations that further bridge the gap between biological and artificial intelligence. Future neuromorphic systems may revolutionize how we interact with technology, offering smarter, more responsive, and highly efficient computational models that integrate seamlessly into everyday life.

The ideas of policy improvement, iteration, and optimality map onto how neuromorphic systems learn and adapt.

Neuromorphic circuits often rely on algorithms like reinforcement learning or Hebbian learning, where policies (rules of behavior) evolve based on feedback from the environment [

26]. As an example, Hebbian learning rules in the context of Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP) experiments involve neuromodulators. Early STDP experiments primarily focused on the tonic bath application of modulatory factors. STDP under the control of ‘neuromodulators’ leads to the framework of three-factor learning rules. In this framework, an eligibility trace represents the Hebbian idea of co-activation of pre- and postsynaptic neurons, while modulation of plasticity by additional gating signals is represented by a ‘third factor’ [

27]. “This third factor could represent variables such as ‘reward minus expected reward’ or the saliency of an unexpected event.” [

27], p. 2. Similarly, in our discourse, residents iterate over their strategies (cooperate or defect) based on social norms, reputation, and experiences, akin to how a neuromorphic system adjusts its responses based on previous inputs to achieve optimal results. In essence, just as neuromodulators influence the plasticity of neural connections based on the timing and context of stimuli,

agents in a social environment adjust their behavior based on the outcomes of previous interactions. For example, positive experiences and a good reputation may encourage cooperation, while negative experiences and a damaged reputation may lead to defection. This iterative process helps agents optimize their behavior to achieve the best possible outcomes in their environment. In line with reference [

28], pag. 2, we assume that “in the presence of reputation effects,” people are akin to cooperation, because when individuals can build a reputation, their past actions serve as a signal to others about their future behavior. For instance, if a recipient is known to reward cooperation, donors are more likely to cooperate because they anticipate being rewarded. This creates a positive feedback loop where cooperation is encouraged and rewarded. From an evolutionary perspective, individuals who cooperate and reward cooperation are more likely to be imitated and have their strategies spread through the population. This is because these strategies lead to higher payoffs, making them more attractive for others to adopt. Always from an evolutionary perspective, strategies evolve through imitation and random exploration. The results align with the equilibrium predictions, showing that higher information transmissibility leads to cooperation and social rewarding [

28], pagg. 2-4.

Neuromorphic sensors are designed to respond to environmental changes in real-time, just as residents’ actions are influenced by their context (social norms, power dynamics, reputations, and expectations). Neuromorphic systems, like human behavior, depend heavily on real-time data to make adaptive decisions.

In a CIP-BP scenario, the probabilistic impact is seen as learning to optimize actions (like pressing buttons) despite the probabilistic nature of the outcomes they generate. The agent must decide whether to continue exploring new actions with uncertain outcomes (where probabilistic effects come into play) or to exploit actions that are known to work well. Since the environment may not always provide consistent outcomes (due to the probabilistic impacts), Q-learning [

6] is designed to handle these variations, updating its knowledge based on expected future rewards. Below is a representation of the key dimensions and indicators drawn from the survey that directly inform the layered design of the interoperable intercom platform.

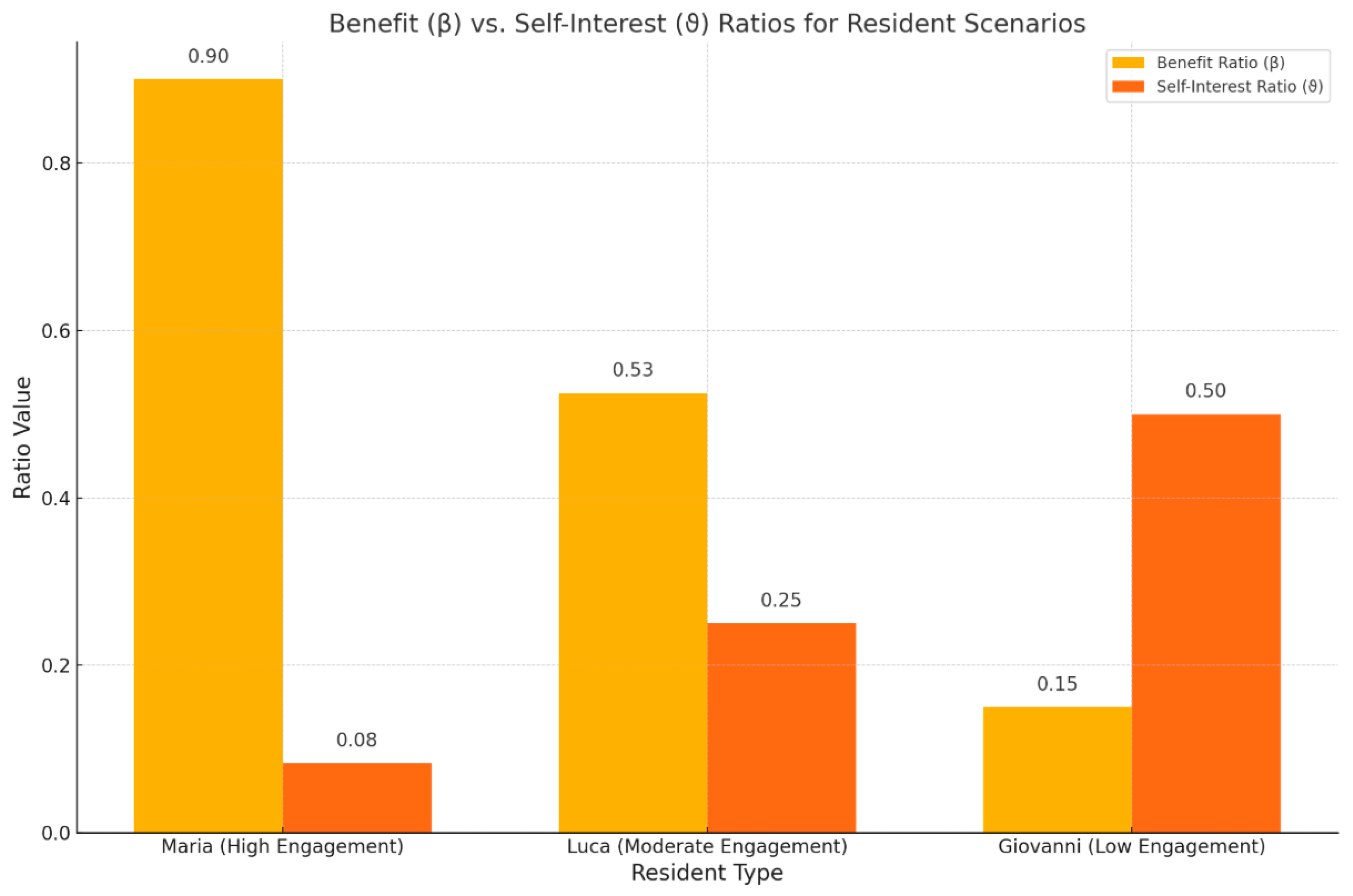

As shown in

Figure 3 above, three representative resident profiles—Maria (high engagement), Luca (moderate engagement), and Giovanni (low engagement)—display markedly different patterns in their Benefit-to-Self-Interest ratios. Maria exhibited a high cooperative benefit ratio (β = 0.90) relative to a minimal self-interest tendency (θ = 0.08), suggesting strong alignment with community goals and positive responsiveness to CIP-BP cues. Luca’s intermediate values (β = 0.53, θ = 0.25) reflect a more ambivalent behavioral orientation, where participation emerged contextually, often reinforced by reward cues. In contrast, Giovanni showed a reversed trend (β = 0.15, θ = 0.50), highlighting resistance to shared norms and a preference for self-serving behavior. These results underscore the CIP-BP’s capacity to differentiate behavioral types and adapt feedback strategies accordingly, fostering an inclusive yet behavior-sensitive governance interface.

3.1. Design Incorporating Game Theory and Behavioral Incentives

In our paper, Game Theory’s “bounded rationality” mirrors how neuromorphic systems deal with incomplete or uncertain information. For example, the CIP-BP could optimize communication and security in real-time, using limited information about residents’ availability, preferences, or security protocols.

We have searched to integrate the best of Game Theory’s exploration of the potentialities of representational theory using very simple technical tools, taking advantage of a mix of i. arithmetic and number theory studies on the patterns of numbers and counting; ii. logic modes to mimic patterns of reasoning; iii. probability inputs to handle patterns of chance; and iv. topology to deal with patterns of closeness and position to agents’ expectations.

We translate all of them into how different modules or neurons within a neuromorphic system interact or share resources efficiently. For instance, instead of a resident deferring or cooperating in the game-theoretic sense, the panel’s different “neuronal” parts could cooperate to decide access or initiate a communication protocol based on past successful interactions.

The CIP-BP learns from recurring interaction patterns—adjusting access prioritization, response strategies, and signal intensity based on community usage. Actions that fail to produce expected outcomes (e.g., misdirected calls or failed entry requests) are gradually de-emphasized, while successful patterns are reinforced.

This is achieved through:

Probabilistic Updating: Behavioral choices (e.g., pressing a specific button) are modeled as probabilistic state-action pairs, whose expected utility (Q-value) is continuously updated based on outcomes.

Look-Ahead Control: Predictive modeling (e.g., whether a behavior will disrupt or support communal harmony) is embedded into access protocols, similar to dynamic control systems in neuromorphic chips.

Behavioral Replacement: Previous access patterns are revised over time to optimize future decision-making, similar to neural pruning and synaptic strengthening.

These dynamics collectively frame the intercom panel as a living interface, capable of “learning” the behavioral rhythms of the building and adjusting response hierarchies to align with collective well-being.

3.2. Scoring and Incentivization Through Behavioral Feedback

Inspired by the carrot-and-stick model and game-theoretic principles, the CIP-BP introduces a scoring system to incentivize cooperative behaviors and discourage antisocial ones. This system aims to balance individual freedom with collective accountability, encouraging voluntary adherence to community norms through gamified feedback. Key characteristics of this behavioral architecture include:

Look-Ahead Behavioral Forecasting: Drawing on Liao et al. (2024) and Brinkmann’s look-ahead policies, the system predicts how specific actions (e.g., ignoring security protocols) may negatively impact the broader system, adjusting scores accordingly.

-

Behavioral Triggers:

- ∘

Positive: Participating in community events, maintaining quiet hours, assisting elderly neighbors.

- ∘

Negative: Repeated rule violations, misuse of emergency protocols, ignoring visitor verification.

Access Modulation: Scores influence access features—priority call routing, door unlock delay adjustments, or community perks (e.g., newsletter recognition).

Legal and Structural Anchoring: Echoing Luhmann’s theory of social systems, the system stabilizes expectations over time through clear rules and consistent feedback loops, creating a self-regulating behavioral standard.

Our CIP-BP panel uses ‘the carrot and stick mechanism,’ also known as ‘the carrot and the whip,’ is a metaphorical approach to motivation and behavior management that involves offering rewards (the carrot) for desirable behavior and imposing penalties or punishments (the stick) for undesirable behavior [

29]. In the context of a condominium community, this mechanism can play a significant role in shaping residents’ behaviors, especially in promoting cooperation, compliance with rules and regulations, and overall ethical conduct. It should aim to foster self-regulation and internalization [

30] of community norms and values among residents. By consistently rewarding cooperative behavior and sanctioning misconduct, the mechanism helps to reinforce positive social norms and discourage behaviors that deviate from community standards. Over time, “norm recognizers” more than merely “social conformers” [

31], p. 348 can contribute to a culture of mutual respect, trust, and cooperation within the condominium community, reducing the need for external enforcement and reliance on the carrot and stick approach. While the limited sample size utilized during surveys may reduce statistical power, and thus the capacity to detect significant effects, this limitation has been accounted for in the interpretation of results. A small sample requires a larger effect size to reach statistical significance, and the confidence intervals around estimates may be wider, reflecting lower precision.

Nevertheless, the integration of qualitative feedback, drawn from open-ended questions and mobile interviews, has added contextual richness and strengthened the overall analysis by capturing perceptions, motivations, and behavioral nuances that purely quantitative data may miss in the below sample drawn from self-reported population characteristics.

The “carrot” aspect of the mechanism involves offering incentives, rewards, or positive reinforcement to encourage residents to engage in cooperative behaviors and adhere to ethical standards. This could include:

- a)

recognition or praise for individuals or groups who demonstrate exemplary behavior,

- b)

tangible rewards such as discounts on association fees or amenities, or

- c)

opportunities for community involvement and leadership roles.

By highlighting the benefits of cooperation and ethical conduct, the carrot aspect encourages residents to align their behavior with the values and goals of the community.

Conversely, the “stick” aspect of the mechanism involves imposing consequences, penalties, or disciplinary measures to deter residents from engaging in behaviors that violate rules, disrupt community harmony, or undermine collective well-being [

32]. This could include fines for rule violations, suspension of privileges or access to community amenities, or even legal action for serious misconduct. The stick aspect serves as a deterrent against unethical or antisocial behavior, sending a clear message that there are consequences for actions that harm the community or its members. The mechanism can be also rather impalpable considering that residents are likely to form “empirical beliefs about others’ average cooperation”, and this in turn becomes a determinant of “cooperation levels” that individuals will be willing to embrace on the basis of how much higher the incentive is to cooperate since the cooperation of others, as clearly highlighted by reference [

33], p. 461.

The effective use of the carrot and stick mechanism requires striking a balance between rewards and consequences, ensuring that incentives are aligned with desired behaviors and penalties are proportionate to the severity of infractions [

34]. By establishing clear expectations, rules, and guidelines for behavior, the mechanism reinforces a sense of collective responsibility and accountability among residents. Consistent enforcement [

35] of both positive and negative consequences [

36] helps to maintain order, fairness, and trust within the community, reinforcing the “expectations of expectations” by Niklas Luhmann mentioned in sub-paragraph

2.2.3. Linking Shared Responsibility to Behavioral Design.

Very important, effective communication [

37] is essential for implementing the carrot and stick mechanism in a condominium community.

Residents should be informed about community rules, expectations, and the consequences of non-compliance through clear communication channels, such as newsletters, community meetings, online platforms, and mobile chats. Additionally, opportunities for resident input, feedback, and participation in decision-making processes can enhance transparency, accountability, and buy-in for the CIP-BP mechanism.

3.3. Hypotheses for Cooperative Behavior in Condominium Systems

Given the structured, self-contained nature of condominium communities, we propose the following hypotheses to guide the analysis of the CIP-BP model:

H1: System/Environment Difference

This hypothesis suggests that condominiums function as distinct social systems with clearly defined boundaries separating them from their surroundings. This boundary is reinforced through physical infrastructure (e.g., controlled access points) and social norms, creating a strong sense of identity and belonging among residents. Testing this hypothesis will help determine the extent to which residents perceive their community as separate from the external environment, influencing their cooperative behaviors and sense of collective responsibility.

H2: Allopoiesis/Autopoiesis and Operational Closure

This hypothesis explores whether condominiums exhibit characteristics of allopoietic (externally driven) or autopoietic (self-sustaining) systems, focusing on operational closure and self-regulation. It aims to assess whether condominium governance can independently manage internal functions, enforce norms, and adapt to environmental changes without direct external intervention. Understanding this dynamic is critical for modeling the decision-making processes that underpin the CIP-BP’s incentivization mechanisms.

H3: Symbolically Generalized Media and Codes

This hypothesis examines the role of symbolically generalized media and codes (e.g., access cards, digital tokens, intercom notifications) in facilitating communication and establishing norms within condominium communities. These symbolic systems serve as the 'language' through which residents coordinate actions, share information, and manage collective risks. Investigating this hypothesis will reveal how communication channels and codes influence resident behavior, decision-making, and collective identity.

H4: Influence on Decision-Making and Communication

This hypothesis posits that factors such as system/environment differentiation, operational closure, and symbolically generalized media significantly shape decision-making processes within condominium communities. It suggests that the organizational behavior observed in such settings reflects a complex interplay of internal norms, external influences, and feedback loops, which together define the community’s resilience and adaptive capacity.

Neuromorphic Engineering Principles

By linking neuromorphic engineering, the intercom system is framed as one that learns, adapts, and makes optimized decisions for the condominium, much like how the human brain processes complex decisions efficiently with limited resources. Neuromorphic means the intercom panel functions like a brain-inspired system that adapts and learns from its environment. Just as humans adjust decisions based on experience, the intercom system adjusts its behavior based on the interactions and feedback from residents and visitors. It does not need perfect information or massive computational power—it learns and optimizes decisions through repeated interactions, much like a human learning over time.

Adaptation: Neuromorphic systems are built to adapt over time, learning from past interactions. This is similar to how game-theoretic agents evolve their strategies (e.g., cooperation) to improve outcomes.

Low Power Consumption & Efficiency: Neuromorphic systems, like human brains, are highly efficient in making complex decisions using minimal resources. This efficiency can be mirrored in how condominium systems should function optimally without needing vast computational power.

Real-Time Processing: Like in repeated games where real-time decisions affect outcomes, the intercom panel must respond to dynamic inputs (residents’ requests, visitor access, security updates) efficiently and rapidly.

The intercom panel incorporates game-like elements using a scoring system to monitor and incentivize resident behavior. Inspired by evolutionary game theory, the scoring Carrot & Stick mechanism encourages cooperation and discourages anti-social behaviors by adjusting the rewards or penalties based on an individual’s actions. This requires striking a balance between rewards and consequences, ensuring that incentives align with desired behaviors and penalties are proportionate to the severity of infractions [

15]. This is analogous to cooperative game dynamics, where individuals must balance personal gains with collective well-being [

16].

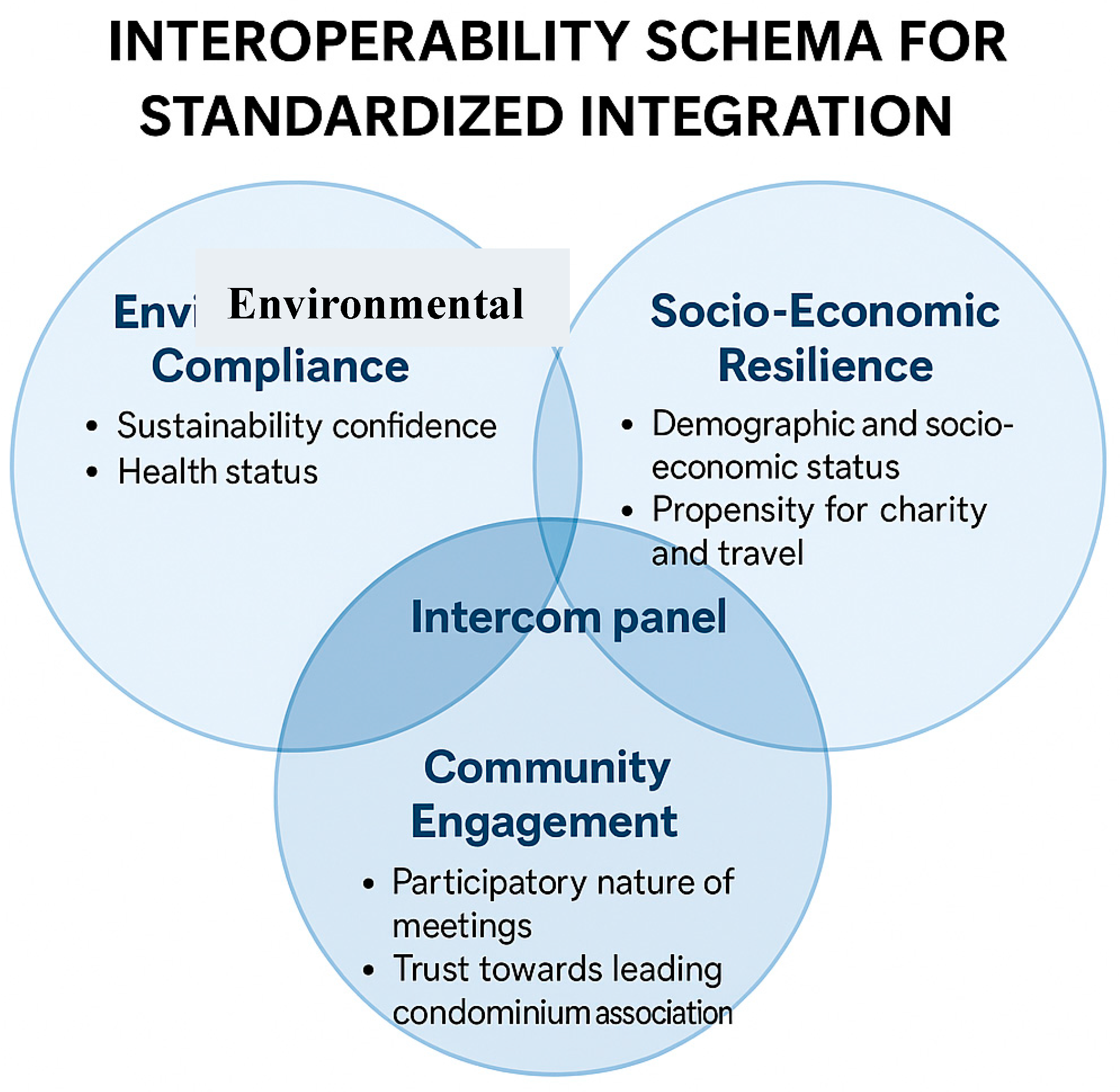

To ensure that the Intercom Panel functions not only as a behavioral interface but also as a scalable, resilient, and policy-relevant tool, an

interoperability framework was mapped. This framework supports integration across three core domains:

technical system design,

human behavioral incentives, and

institutional feedback loops. The

Venn diagram below (Figure 4) illustrates the convergence of these components, providing a visual model of how standardization efforts can align with smart living environments and social cooperation strategies.

Residents are assigned scores that reflect their behavior over time, and various factors, such as compliance with community rules, interactions with other residents, and participation in building-wide initiatives, can influence these scores. The system’s look-ahead mechanism elucidated in reference evaluates potential outcomes of a resident’s actions and adjusts their score accordingly. For example, engaging in activities that reduce noise or energy consumption might trigger rewards, while disruptive behavior might lead to temporary restrictions on certain privileges.

3.4. Privacy and Ethical Considerations

Implementing a system that monitors and evaluates resident behavior raises significant privacy concerns. The design of this intercom system includes built-in safeguards to ensure that resident data is handled with care, following principles of privacy by design. Consent mechanisms are incorporated into the system, allowing residents to opt into specific features. Additionally, the system provides complete transparency, enabling residents to review their scores and understand how their actions influence their standing within the community.

To maintain trust and ensure fairness, the system allows for resident feedback and offers mechanisms for dispute resolution. Residents can appeal decisions or request explanations for changes in their scores, promoting accountability and transparency in how the system operates.

The probabilistic nature of action outcomes can significantly make attributing rewards to specific actions complex when the rewards are delayed. The learning algorithm must infer the expected value of actions even when the results are uncertain.

We are supposing a scenario where pressing a button only sometimes leads to the same response or outcome. For example:

Pressing the button “A1” may usually open the door, but due to probabilistic effects (e.g., malfunction, delay, or noise in the system), it may sometimes fail or take longer.

The system (agent) could use a learning algorithm like Q-learning to adjust its strategy based on these probabilistic outcomes, refining its behavior to maximize success (e.g., learning to press the button more often or with different timing).

The agent could learn that while pressing "A" has a high chance of success, pressing "B" may have a lower success rate but occasionally offers a better reward. The probabilistic nature of these outcomes would influence how the agent updates its Q-values, learning to act optimally in the face of uncertainty.

The CIP-BP Intercom Push-Button Panel is not a neuromorphic system, but it behaves similarly in some ways when applying Q-learning or another reinforcement learning algorithm. Like a neuromorphic system, it learns from feedback. It adjusts its behavior (changing which button to light green, for example) based on the rewards it receives (such as successfully making a call or opening a door).

3.5.‘. Neuromorphic Replacement’ as a Concept

In terms of hardware, the intercom panel incorporates both audio and video communication functionalities, ensuring that residents can interact with visitors securely. The system is also designed to be future-proof, combining wired and wireless communication technologies [

18]. The push-button interface is intuitive, but residents can access the system via smartphone or tablet applications for remote operation.

Applying game theory concepts such as Nash equilibrium or cooperative strategies to design a system like the FUCAR neu/25 intercom panel provides an innovative approach. For example, by ensuring each apartment has its own designated button, the design eliminates potential conflicts over shared resources (such as a single entry point for multiple units), encouraging a harmonious user experience. The LED-lit buttons further add a layer of ease and visibility, optimally catering to each resident’s needs.

4. Design Outcomes and Learning-Driven Functionality

From a design standpoint, the Condominium Intercom Push-Button Panel (CIP-BP) serves as a cooperative technological infrastructure addressing the shared challenge of secure, efficient, and equitable access to residential buildings. Designed for a medium-density condominium with approximately twenty-five residents, the panel incorporates both architectural and cognitive usability principles to ensure clarity, prevent congestion, and enhance accessibility for all users, including elderly residents.

The modular design allows the system to scale with the number of residents, while preserving intuitive usability through dedicated buttons and integrated features. Each apartment is assigned a specific button or digital tag, preventing shared entry points that might otherwise lead to confusion or disputes over access control.

The IP-BP integrates traditional audio-video communication with next-generation behavioral intelligence. Below are its primary functionalities, structured according to smart infrastructure standards:

Individualized Call Routing: Enables one-to-one communication between visitors and residents via audio interface, ensuring secure visitor identification and preserving private communication flows.

Remote Access Management: Residents can grant or deny access via connected mobile or landline devices, facilitating both convenience and active control over entry events.

Multi-Unit Navigation: Designed to support 20+ units with individual push-buttons or a digital directory, ensuring scalability without compromising user experience.

Visual Signaling: Each button includes red LED indicators for visibility in low-light environments. Blinking patterns serve as feedback cues, reinforcing awareness of usage behavior without requiring intrusive surveillance (e.g., cameras).

Durability for Outdoor Deployment: Constructed from weather-resistant aluminum to maintain functionality under extreme temperature, humidity, or precipitation.

Emergency Protocol Integration: Capable of routing distress signals to security personnel or emergency responders during health or safety crises.

-

Accessibility and Inclusion:

- ∘

RFID Priority Tags: Issued to elderly or mobility-impaired residents to prioritize their requests automatically.

- ∘

Time-Based Support: Extended interaction windows for users needing additional time to respond, ensuring universal usability without digital exclusion.

Smart Queueing: Auditory feedback systems communicate the sequence of visitor calls to help residents prioritize responses, especially during peak traffic.

Delivery Management: Enables secure communication with couriers and remote door access for unattended package drop-offs.

Ambient Feedback Loops: Polite chimes or musical cues signal visitor presence, reducing stress and promoting a welcoming environment.

The FUCAR neu/25 CIP-BP, currently deployed in the study and sketched below in

Figure 5, is a high-quality, weatherproof solution supporting both commercial and residential applications. Its design provides a practical model for inclusive smart living systems, aligned with evolving needs in

standards for smart infrastructure.

5. Digital Twin (DT) Modelling and Behavioral Learning Integration

The behavioral scoring logic embedded in the Intercom Panel can be further expanded and validated through Digital Twin (DT) technology, which enables real-time, virtual mirroring of resident interactions, device responses, and access dynamics within the condominium ecosystem. This DT layer functions as a predictive simulation environment for optimizing both system design and human-machine interaction protocols. By coupling real-time data streams from the panel with simulation models, the Digital Twin serves as a behavioral sandbox: it allows designers and administrators to anticipate congestion patterns, adjust access prioritization strategies, and simulate the effects of community-level behavior shifts on the overall operational flow. Such applications make the Intercom Panel not just a front-line access point, but also a feedback-rich interface for socio-technical learning, reinforcing the sustainable and inclusive goals of smart residential infrastructure.

To structure this complexity and align with interoperability and standardization principles, the system’s architecture can be formally articulated using Model-Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) methodologies. MBSE provides a systematic and traceable approach to modeling the interdependencies between hardware components (e.g., RFID sensors, LED interfaces), software logic (e.g., scoring algorithm, learning policy updates), and stakeholder interactions (e.g., residents, administrators, emergency services). In the context of the IP-BP, MBSE facilitates the formal integration of behavioral feedback loops, equity-based access logic, and SDG-aligned indicators (such as inclusion of vulnerable residents, energy efficiency, and democratic governance of shared spaces). This modular and scalable framework allows for rigorous validation of both technical functionality and social impact, thus embedding sustainability not merely as an outcome, but as a structural constraint throughout the design lifecycle.

5.1. Simulated Environment and Policy Design through Digital Twin (DT) and MBSE

To advance beyond a reactive intercom system and toward a model of anticipatory governance, we propose the integration of a Digital Twin (DT) architecture that mirrors real-time interactions between residents, intercom functionalities, and collective behavioral profiles. This simulated environment is based on the two-round panel survey data collected from the condominium, capturing variables such as economic resilience, educational adaptability, healthcare access, and trust in governance. By embedding this data within a DT framework, designers can replicate behavioral responses under different scenarios, such as pandemic alerts, aging population shifts, or changes in communal voting structures, allowing system designers and administrators to evaluate the efficacy of alternative policies before physical implementation. Within this simulation, each resident becomes an agent whose scoring, risk exposure, and cooperation threshold evolve based on both pre-survey data (e.g., GShs, PfCT) and emergent interactions, enabling agent-based modeling (ABM) to trace both individual adaptation and systemic resilience under stress.

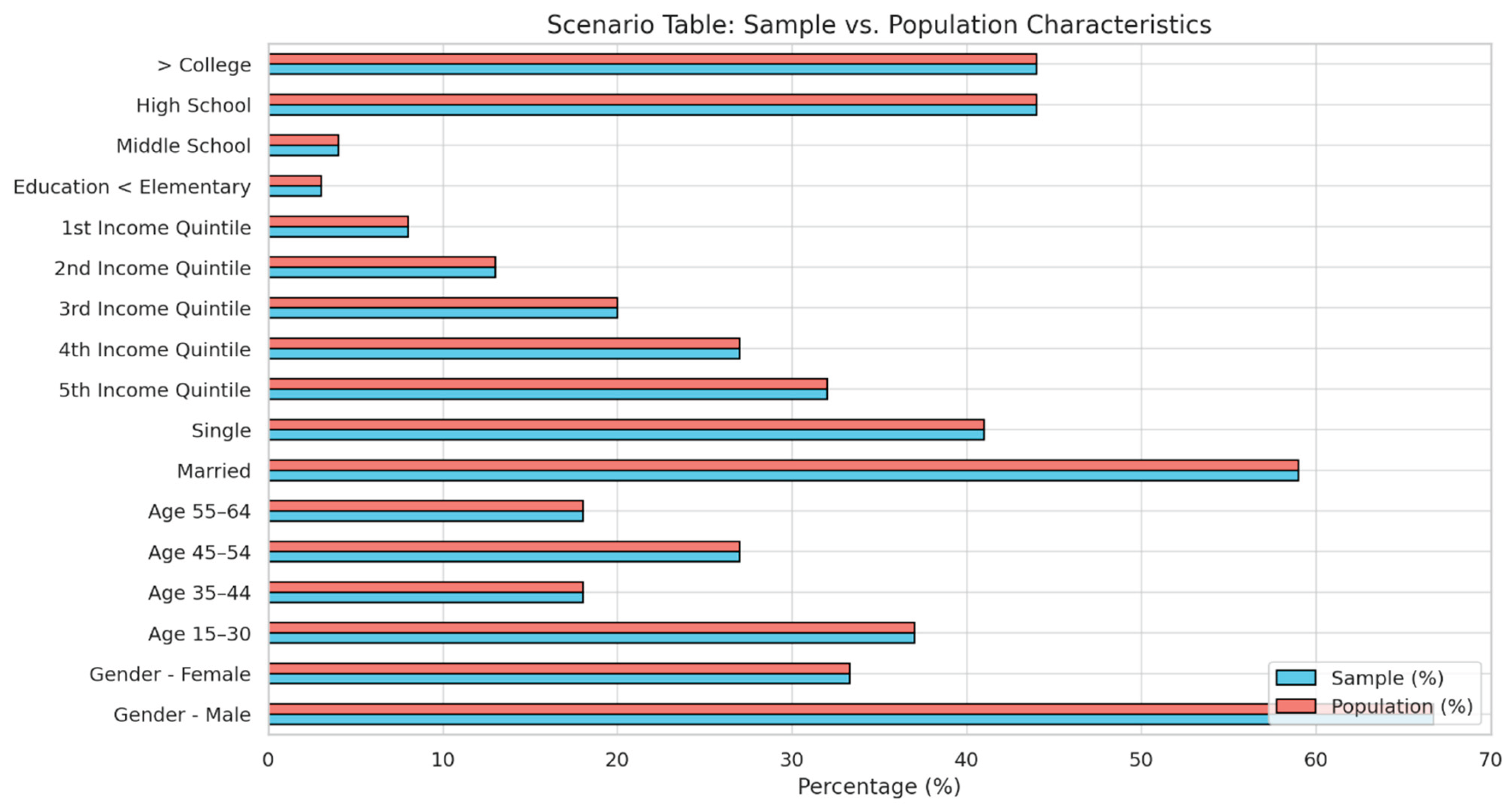

The above horizontal bar chart in

Figure 6 visualizes the primary demographic features of the interviewed condominium population. It includes gender distribution, age brackets, marital status, income quintiles, and educational levels. The most prevalent groups are male residents (66.7%), those aged 15–30 and 45–54 (37% and 27%, respectively), individuals in the top income quintiles (32% in the 5th and 27% in the 4th), and those with high school or college education (44% each). The chart complements Table 2 by summarizing key socio-demographic variables affecting social capital, sustainability perceptions, and behavioral adaptation in shared residential settings.

5.2. Interoperability and Feedback Loops

The consideration of intrinsic and extrinsic individual differences, as well as the dimensions related to learning tasks, content, and procedures employed, adds a layer of complexity to the analysis. This approach recognizes the multifaceted nature of individual differences and their potential impact on learning, memory, and response to the stimuli of condominium’s regulations. Aligned with Model-Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) principles, the intercom system is further modeled through interoperable layers: (1) the user interaction layer (resident-panel feedback), (2) the logic layer (scoring, behavior rules, learning mechanisms), and (3) the policy-control layer (admin oversight, emergency protocols, time-based access rules). Survey data—including EE-res indicators such as Technological Adaptability, Crisis Preparedness, and Trust in Leadership—are embedded as system parameters that dynamically adjust incentive mechanisms (e.g., audio prompts, access delay, visual alerts). For instance, if trust scores decline across rounds, the system flags the governance panel and simulates the impact of alternative participatory mechanisms (e.g., adding open forums, implementing digital voting). This ensures that interoperability is not only technical but also institutional, with real-time feedback loops supporting adaptive regulation, inclusive participation, and digital ethics compliance. The intercom panel thus functions as a behavioral-policy interface—one that listens, learns, and evolves in sync with the needs and capacities of its user base.

6. Discussion

In the face of accelerating urbanization and the widespread diffusion of multi-unit housing, the implementation of agile and inclusive digital governance tools becomes essential, not only for achieving efficiency in shared spaces but also for nurturing a culture of participation and trust. The CIP-BP represents a low-tech yet cognitively informed prototype for governing communal environments in a bottom-up fashion. Drawing inspiration from the foundational work of Watkins (1989) in reinforcement learning and from socio-cybernetic theories of self-regulating systems (Luhmann, 1984), the CIP-BP enables residents to interact with shared infrastructure while simultaneously contributing to the formation of localized social norms.

Rather than relying on traditional surveillance or punitive controls, the interface encourages cooperation through subtle cues, personalized feedback, and delayed reward mechanisms. These incentives are shaped by ongoing resident behavior and adapted over time via neuromorphic processing logic. This makes the CIP-BP not just a communication tool, but a learning system embedded in the social life of a building.

The system’s architecture is rooted in three interacting mechanisms:

Norm-sensitive reinforcement, leveraging micro-feedback loops to stabilize courteous and energy-efficient actions;

Community-weighted utility calculations, aligning personal convenience with collective benefit;

Long-term incentivization, using deferred but meaningful rewards to strengthen behavioral resilience and trust-based coordination.

Field tests in a small condominium in Agrigento, Sicily, revealed promising behavioral shifts: increased responsiveness to others' needs, improved hallway etiquette, and a noticeable decline in resident disputes. The device's simplicity allowed for rapid deployment, minimal cost, and unexpected emotional engagement by elder residents, who appreciated both the analog tactility and the clarity of purpose embedded in its design.

These qualitative impressions were further reinforced by behavioral patterns observed across different resident profiles. Individuals with high levels of engagement exhibited a strong orientation toward collective benefit, with cooperative behavior significantly outweighing self-interested actions. In contrast, less engaged residents displayed an inverted pattern, with self-interest dominating over communal considerations. Intermediate profiles showed a more nuanced balance, suggesting that engagement levels could be dynamically modulated through personalized feedback and targeted reinforcement. These observed asymmetries in the benefit-to-self-interest ratios reveal the potential of the CIP-BP to adaptively shape resident behavior, offering differentiated incentives and regulatory cues based on the evolving interaction history of each user. Such differentiation enhances the inclusiveness and behavioral sensitivity of the system, strengthening its ability to support long-term cooperative dynamics within heterogeneous communities.

By combining principles from behavioral economics, systems thinking, and human-centered design, the CIP-BP exemplifies how even basic technology—when integrated with social logic—can yield scalable governance tools. Its potential extends beyond housing: from eldercare and micro-neighborhood hubs to participatory planning in smart cities. The system demonstrates how modest digital infrastructures, when modeled on collective rationality and emergent coordination, can function as catalysts for social innovation.

7. Conclusions

By embedding adaptive decision-making logic directly into the architecture of a traditionally passive device—the condominium intercom—the CIP-BP redefines the potential of everyday technology as a vehicle for behavioral governance. Rather than serving as a mere access control point, the interface evolves into a relational platform: it mediates not only physical entry but also the symbolic boundaries of cooperation, attention, and civic-mindedness among residents.

This shift from static infrastructure to participatory governance tool underscores a broader transformation in how communities can self-organize in the face of urban complexity. The CIP-BP does not impose behavior from above but facilitates the emergence of local norms through real-time interaction and feedback. In doing so, it reinforces micro-acts of mutual care and accountability—elements often lost in anonymous residential settings.

Crucially, the system’s low-cost design and ease of implementation make it suitable for replication in diverse socio-economic contexts, particularly in Southern European or Mediterranean urban environments, where interpersonal density coexists with infrastructural fragility. Moreover, its capacity to support elderly and vulnerable populations through intuitive signaling and delayed-reward mechanisms highlights its inclusivity and social sensitivity.

The CIP-BP thus offers a pragmatic and scalable contribution to the challenge of sustainable urban living. It aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (especially SDG 11) not through high-end automation or surveillance, but through the cultivation of everyday cooperative habits. As cities continue to grow and age demographically, such models—grounded in behavioral insight and simple feedback loops—may become indispensable components of equitable, adaptive, and human-centered governance systems.

While this version of the CIP-BP remains predominantly conceptual—prioritizing behavioral modeling, systemic design, and sociological integration—it lays the groundwork for future technical developments. The integration of energy-efficient hardware components, secure signaling protocols, and adaptive feedback mechanisms will require collaboration with practitioners in electrical engineering, systems architecture, and smart infrastructure deployment. Such interdisciplinary refinement will be essential to bring the CIP-BP from prototype to broader implementation, ensuring both robustness and ethical scalability.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used: Conceptualization, R.F. and S.C.; methodology, R.F.; software, R.F.; validation, R.F. and F.R.; formal analysis, R.F.; investigation, R.F.; resources, R.F.; data curation, R.F. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.; writing—review and editing, R.F.; visualization, R.F., P.A., and F.R.; supervision, R.F.; project administration, R.F., P.A., and S.C.; funding acquisition, R.F. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the self-referenced nature of the data utilized to provide the technical intercom panel.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All participants were briefed on the purpose of the research and participated on a voluntary basis. No personal data, sensitive information, or health-related identifiers were collected or disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the University of Verona, Department of Management, for its support during the development of this research. Special thanks are extended to colleagues and residents who contributed to the pilot testing phase with their time, insights, and trust.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Velikov, Kathy, and others, 'Empowering the Inhabitant: Communications Technologies, Responsive Interfaces, and Living in Sustainable Buildings', in Rebecca L. Henn, and Andrew J. Hoffman (eds), Constructing Green: The Social Structures of Sustainability (Cambridge, MA, 2013; online edn, MIT Press Scholarship Online, 23 Jan. 2014). accessed 10 May 2025. [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, D., Barricelli, B.R., Fogli, D. Enhancing Sustainability in Smart Home Management with Automation Simulations and Green Suggestions. IUI ′25: Companion Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, March 2025, pp. 35-38. https://dl.acm.org/doi/proceedings/10.1145/3708557.

- Martins, F., Almeida, M. F., Calili, R., & Oliveira, A. (2020). Design Thinking Applied to Smart Home Projects: A User-Centric and Sustainable Perspective. Sustainability, 12(23), 10031. [CrossRef]

- Gračanin, D. et al. (2011). Mobile Interfaces for Better Living: Supporting Awareness in a Smart Home Environment. In: Stephanidis, C. (eds) Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Context Diversity. UAHCI 2011. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 6767. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Gullà, F., Ceccacci, S., Menghi, R., Cavalieri, L., Germani, M. (2017). Adaptive Interface for Smart Home: A New Design Approach. In: Cavallo, F., Marletta, V., Monteriù, A., Siciliano, P. (eds) Ambient Assisted Living. ForItAAL 2016. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, vol 426. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.J.C.H. Learning from Delayed Rewards. Thesis submitted for PhD, King’s College, 1989, pp. 1–242.

- GhaffarianHoseini, A., Dahlan, N. D., Berardi, U., GhaffarianHoseini, A., & Makaremi, N. (2013). The essence of future smart houses: From embedding ICT to adapting to sustainability principles. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 24, 593–607. [CrossRef]

- Schieweck, A., Uhde, E., Salthammer, T., Salthammer, L.C., Morawska, L., Mazaheri, M. Kumar, P. Smart homes and the control of indoor air quality, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 94, 2018, Pages 705-718, ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- Madsen, M.D., Paasch, J.M., and E.M. Sørensen (2022). The many faces of condominiums and various management structures − The Danish case. Land Use Policy, Volume 120, 106273, ISSN 0264-8377. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, E. Common-Interest Housing in the Communities of Tomorrow. Housing Policy Debate 2003, 14(1-2), pp. 203-234. [CrossRef]

- Çağdaş V., Paasch J.M., Paulsson J., Ploeger H., Kara, A. Co-ownership shares in condominium – A comparative analysis for selected civil law jurisdictions. Land Use Policy 2020; Volume 95, 104668, ISSN 0264-8377. [CrossRef]

- Fucà, R., Cubico, S. (2024). Navigating Organization Dynamics: The Real-World Example of Condominium Life in Sicily During the COVID-19 Era in Late 2022-2023. International Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 12(2), 83-104. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Zhang, J. Perceived residential environment of neighborhood and subjective well-being among the elderly in China: A mediating role of sense of community, Journal of Environmental Psychology, Volume 51, 2017, pp. 82–94, ISSN 0272-4944. [CrossRef]

- Muczyński, A. Collective renovation decisions in multi-owned housing management: the case of public-private homeowners associations in Poland. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 2023, 38: 2105–2127. [CrossRef]

- Fucà, R.; Cubico, S.; Leitão, J (2022). The Role of a Condominium’s Association in Adapting, Complying, and Self-Reducing Anxiety in Response to COVID-19 Precautionary Measures. Frontiers in Law, 2022, 1, 35–43, ISSN:2817-2302. [CrossRef]

- Hardie, B., & Rose, C. (2025). What next for tests of the situational model of Situational Action Theory? Recommendations from a systematic review. European Journal of Criminology, 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Lefevor, G.T., Fowers, B.J. Traits, situational factors, and their interactions as explanations of helping behavior, Personality and Individual Differences, Volume 92, 2016, Pages 159–163, ISSN 0191-8869. [CrossRef]

- El Zein, M., Bahrami, B. & Hertwig, R. Shared responsibility in collective decisions. Nat Hum Behav 2019, 3, 554–559. [CrossRef]

- Keshmirian, A., Deroy, O., Bahrami, B. Many heads are more utilitarian than one, Cognition 2022, Volume 220, 104965, ISSN 0010-0277. [CrossRef]

- Febbrajo, A. Funzionalismo strutturale e sociologia del diritto nell’opera di Niklas Luhmann [eng. trans. Structural functionalism and sociology of law in Niklas Luhmann’s work, unpublished]. Milano, Giuffré, 1987, pp. IV-226, ISBN-10: 8814036152.

- Jianfeng Feng, Viktor Jirsa, Wenlian Lu, Human brain computing and brain-inspired intelligence, National Science Review, Volume 11, Issue 5, May 2024, nwae144. [CrossRef]

- Kudithipudi, D., Schuman, C., Vineyard, C.M. et al. Neuromorphic computing at scale. Nature 637, 801–812 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T. Bio-inspired artificial synapses: Neuromorphic computing chip engineering with soft biomaterials, Memories - Materials, Devices, Circuits and Systems, Volume 6, 2023, 100088, ISSN 2773-0646. [CrossRef]

- Soman, S., jayadeva & Suri, M. Recent trends in neuromorphic engineering. Big Data Anal 1, 15 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E., Soh, K., Hwang, S.I., Yang, D.Y., Yoon, J.H. Memristive neuromorphic interfaces: integrating sensory modalities with artificial neural networks. Mater. Horiz., 2025, pp. 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Schuman, C.D., Kulkarni, S.R., Parsa, M. et al. Opportunities for neuromorphic computing algorithms and applications. Nat Comput Sci 2, 10–19 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, W., Lehmann, M., Liakoni, V., Corneil, D., & Brea, J. (2018). Eligibility Traces and Plasticity on Behavioral Time Scales: Experimental Support of neoHebbian Three-Factor Learning Rules. arXiv:1801.05219v1 [q-bio.NC].

- Pal, S., Hilbe, C. Reputation effects drive the joint evolution of cooperation and social rewarding. Nat Commun 13, 5928 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Sasaki, T., Brännström Å., Dieckmann, U. First carrot, then stick: how the adaptive hybridization of incentives promotes cooperation. J. R. Soc. Interface 2015, 12: 20140935. [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.W., Hong, Y.-y., Chiu, C.-y., Liu, Z. Normology: Integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Volume 129, 2015, pp. 1-13, ISSN 0749-5978. [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J., Gavrilets, S., Nunn, N. Norm Dynamics: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Social Norm Emergence, Persistence, and Change. Annu Rev Psychol. 2024 Jan 18;75:341-378. Epub 2023 Oct 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, J.L., Kim, H., & Ki, S. Investigating the Role of Control and Support Mechanisms in Members’ Sense of Virtual Community. Communication Research 2019, 46(1), 117-145. [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., Schurtenberger, I. Normative foundations of human cooperation. Nat Hum Behav. 2018 Jul; 2(7): 458-468. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M., Schopf, D., Lütteken, N., Liu, Z., Storost, K., et al. Carrot and stick: A game-theoretic approach to motivate cooperative driving through social interaction. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2018, Volume 88, pp. 159-175, ISSN 0968-090X. [CrossRef]

- Leibo, J.Z., Zambaldi, V.F., Lanctot, M., Marecki, J., & Graepel, T. Multi-agent Reinforcement Learning in Sequential Social Dilemmas. Adaptive Agents and Multi-Agent Systems 2017, arXiv:1702.03037v1 [cs.MA] 10 Feb 2017.

- Zhang, T., Liu, Z., Pu, Z., and J. Yi, Peer Incentive Reinforcement Learning for Cooperative Multiagent Games. IEEE Transactions on Games 2023, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 623-636, Dec. [CrossRef]

- Richter, G., Raban, D.R., Rafaeli, S. (2015). Studying Gamification: The Effect of Rewards and Incentives on Motivation. In: Reiners, T., Wood, L. (eds) Gamification in Education and Business. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).