Model Inputs, Model Parametrization and Model Accuracy Results

The input feature of the Bayesian LD model only comprises the distance of separation between the corresponding transmitter and the receiver points. The input feature of the ML models include longitude, latitude, elevation, altitude, clutter height, and distance of separation between the corresponding transmitter and the receiver points. The output feature throughout our study is comprising the path loss values corresponding to each input data point. There are a total of 6244 data points along the measurement route. Though, based on decaying characteristics of the signal strength when it propagates from the base station towards different angles, we applied polar coordinate transformation to transform the geographical data into a polar coordinate system before training the model. Thereby, image axis-independent variables (longitude and latitude) are converted into polar coordination consisting of distance and the transmitting signal direction, i.e., Tx-Rx Angle. The Tx-Rx angle is computed by us through translating the longitude and latitude of the points to X-Y geographic points and setting the (X, Y) coordinate values of the transmitter location equal to the reference point (0, 0). The prediction accuracies of the models are evaluated based on splitting the data by a 1:4 training: testing ratio and by means of MAE (mean absolute error), MAPE (mean absolute percentage error), RMSE (root mean square error), and R squared. The overall performances of the 4 Models are presented in

Table 3.

Table 1.

Evaluation of prediction models along route A.

Table 1.

Evaluation of prediction models along route A.

| |

Bayesian Log Distance |

Natural Gradient Boosting |

Explainable Boosting |

Hybrid EBM2NGB |

| MAE |

5.525 |

3.028 |

2.272 |

2.032 |

| MAPE |

0.040 |

0.021 |

0.016 |

0.014 |

| RMSE |

7.214 |

3.855 |

2.928 |

2.671 |

| R Squared |

0.423 |

0.835 |

0.905 |

0.921 |

Table 2.

Evaluation of prediction models along route B.

Table 2.

Evaluation of prediction models along route B.

| |

Bayesian Log Distance |

Natural Gradient Boosting |

Explainable Boosting |

Hybrid EBM2NGB |

| MAE |

5.839 |

2.974 |

2.431 |

2.245 |

| MAPE |

0.045 |

0.021 |

0.017 |

0.016 |

| RMSE |

8.820 |

3.728 |

3.04 |

2.842 |

| R Squared |

0.131 |

0.844 |

0.896 |

0.909 |

Table 3.

Evaluation of prediction models along route C.

Table 3.

Evaluation of prediction models along route C.

| |

Bayesian Log Distance |

Natural Gradient Boosting |

Explainable Boosting |

Hybrid EBM2NGB |

| MAE |

6.673 |

3.532 |

2.623 |

2.070 |

| MAPE |

0.046 |

0.024 |

0.018 |

0.014 |

| RMSE |

8.029 |

4.833 |

3.662 |

2.746 |

| R Squared |

-0.219 |

0.559 |

0.747 |

0.857 |

In order to inference the posterior distribution of the Bayesian LD model, we obtained the (mean, standard deviation) pair values (100.1589, 0.472) and (2.14013, 0.0268) via OLS regression to set as the prior distribution of the parameters

and

, respectively. Obtaining the residuals

is done via subtracting the observed

values in the dataset from the

term as described in the equation (1). We then use the histogram of the overall

s values (depicted in

Figure 1) to describe the

s prior distribution. This results in choosing the normal distribution with (mean, standard deviation) values equal to (0.035, 5.659) as the best fit to

s.

Figure 2.

distribution of best fit to s.

Figure 2.

distribution of best fit to s.

The resulting trace plots with regard to the posterior probability of the parameters

via using No-U-turn sampler (NUTS) implemented in the probabilistic programming package for python PyMC3 are derived in accordance with the equations 1-9 and are depicted in

Figure 2. Each subplot in the left hand side panel comprises 4 different chains, each of them comprising 1000 draws (solid line: chain 1, dotted line: chain 2, dashed line: chain 3, and dot-dashed line: chain 4) from the posterior probability, which are depicted in the right hand side panels of the

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Trace Plot values for the Bayesian Log Distance Model Parameters.

Figure 3.

Trace Plot values for the Bayesian Log Distance Model Parameters.

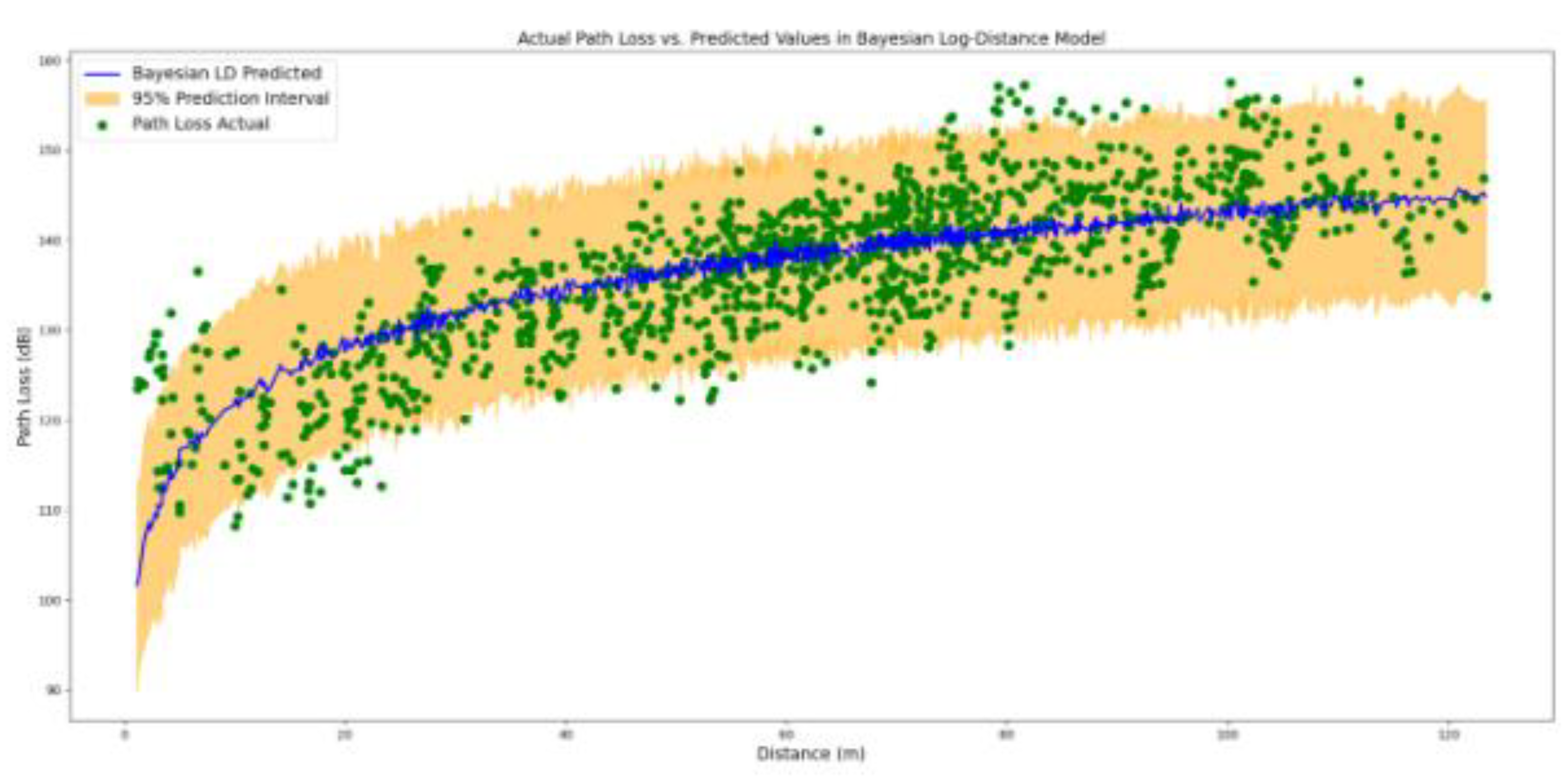

The fitted Bayesian LD model is tested by us on the 20 percent hold-out data set. As prompting the model to predict individual predictions given a specific distance, generates samples of 1000 posterior

values, the results presented in

Figure 4 are comprising the expected mean of the predicted

values together with the lower and the upper 95% confidence interval.

Figure 4.

predicted values together with the lower and the upper 95% confidence interval in Bayesian Log distance Model.

Figure 4.

predicted values together with the lower and the upper 95% confidence interval in Bayesian Log distance Model.

The Bayesian LD model performs well in terms of covering the most points in the 95% of the confidence interval. Though, the suitability of the model to explain the expected predicted points in comparison with a horizontal line drawn at the mean PL value of the training dataset is not optimal. This is reflected in the R-squared value of the model, that represents the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (PL) that is explained by the independent variable (d), which is equal to 0.569. Indeed, only 56.9 percent of the variation in PL values is being explained by the factor distance via the Bayesian DL model. To elaborate more on the issue of un-explain-ability we apply ML models to the data.

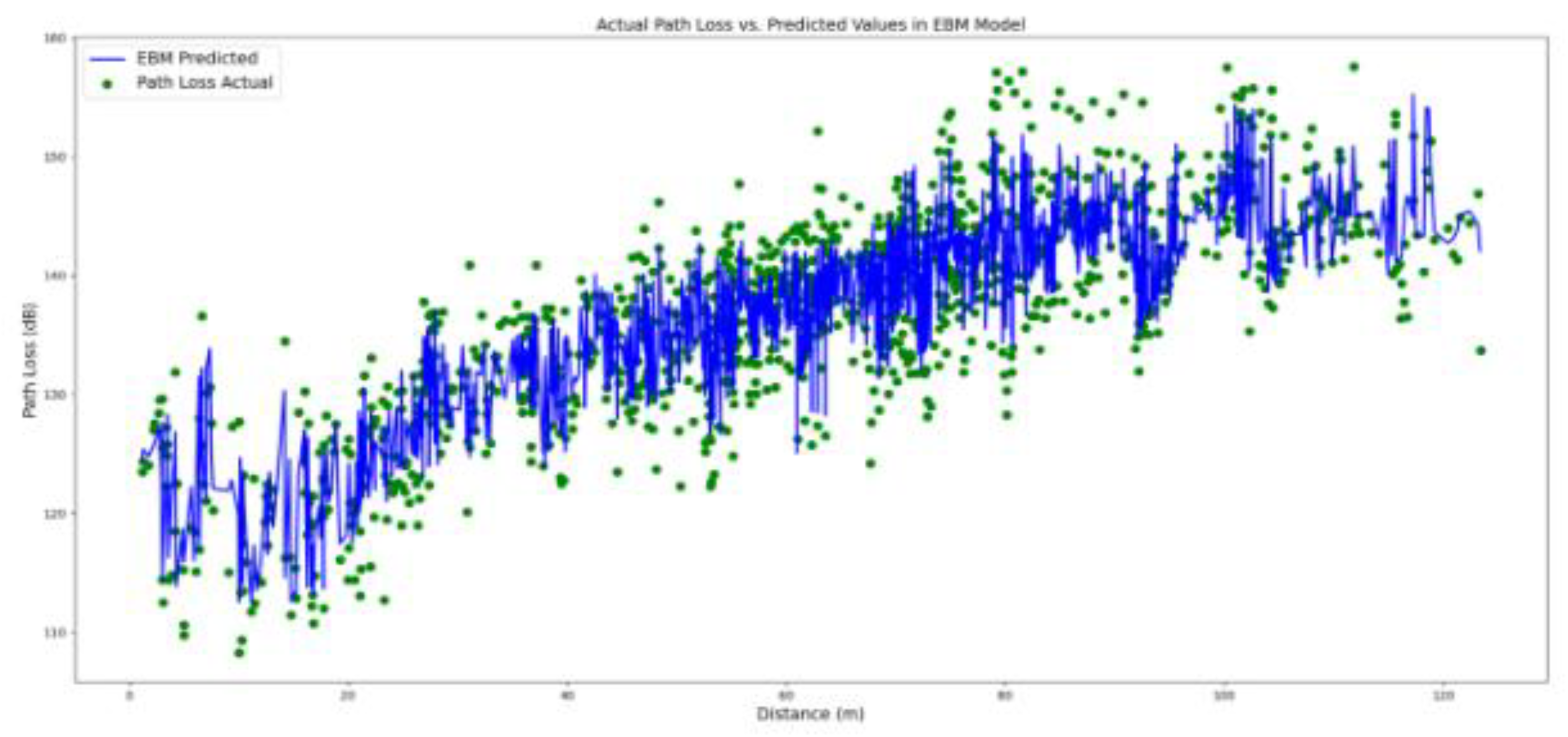

The EBM model trained in this paper is hyper-parametrized by using a grid search through the parameter space: 0.01<“learning_rate” (with 0.01 increments)<0.05, 1<“max_leaves” (integer with 1 increments)<4, 2<“min_samples_leaf ” (integer with 1 increments)<6, “early_stopping_rounds”

[100, 200], and “early_stopping_tolerance”

[1e-6, 1e-5]. It results in utilizing 0.003 as the “learning_rate”, incorporating the “max_leaves” of the trees to be 2, setting the “min_samples_leaf ” equal to 4,“early_stopping_rounds” equal to 100, and the parameter “early_stopping_tolerance” equal to 1e-6 . The results of applying the EBM model on the 20 percent hold-out data based on the distance of separation between the corresponding transmitter and the receiver points as input and the predicted path loss as output are shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

predicted values together with the lower and the upper 95% confidence interval in Explainable Boosting Model.

Figure 5.

predicted values together with the lower and the upper 95% confidence interval in Explainable Boosting Model.

In comparison with the Bayesian LD model, the EBM model performs well in terms of decreasing the MAE, MAPE, and the RMSE metrics to the lower corresponding error values. Especially, the R-squared metrics value is increased up to 0.844. However, the EBM point predictions might be exposed to the over-fitting. To elaborate more on the issue of uncertainty we apply the probabilistic NGB model to the data.

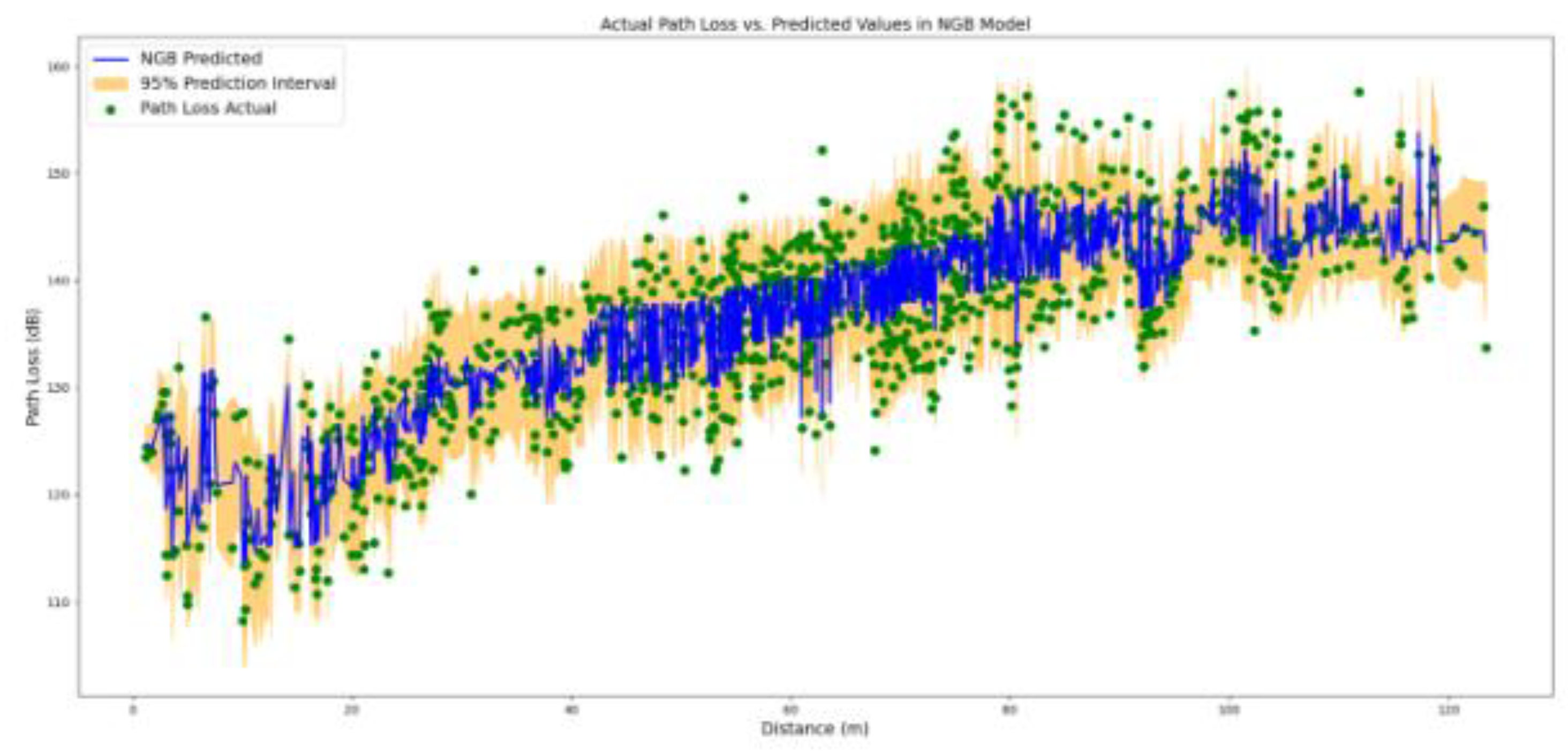

The NGB model trained in this paper is hyper-parametrized by using a grid search through the parameter space: 0.01<“learning_rate” (with 0.01 increments)<0.05, 1<“max_depth” (integer with 1 increments)<4, “minibatch frac“

[0.5, 1.0], 1<“early_stopping_rounds“(integer with 1 increments)<11, and “distribution“

[Normal]. It results in utilizing 0.001 as the “learning_rate”, incorporating the “max_depth” of the trees to be 2, setting the “minibatch frac“

equal to 0.5,“early_stopping_rounds” equal to 10, and the “distribution“ to be Normal. The results of applying the NGB model on the 20 percent hold-out data based on the distance of separation between the corresponding transmitter and the receiver points as input and the predicted path loss as output are shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

predicted values together with the lower and the upper 95% confidence interval in Natural Boosting Model.

Figure 6.

predicted values together with the lower and the upper 95% confidence interval in Natural Boosting Model.

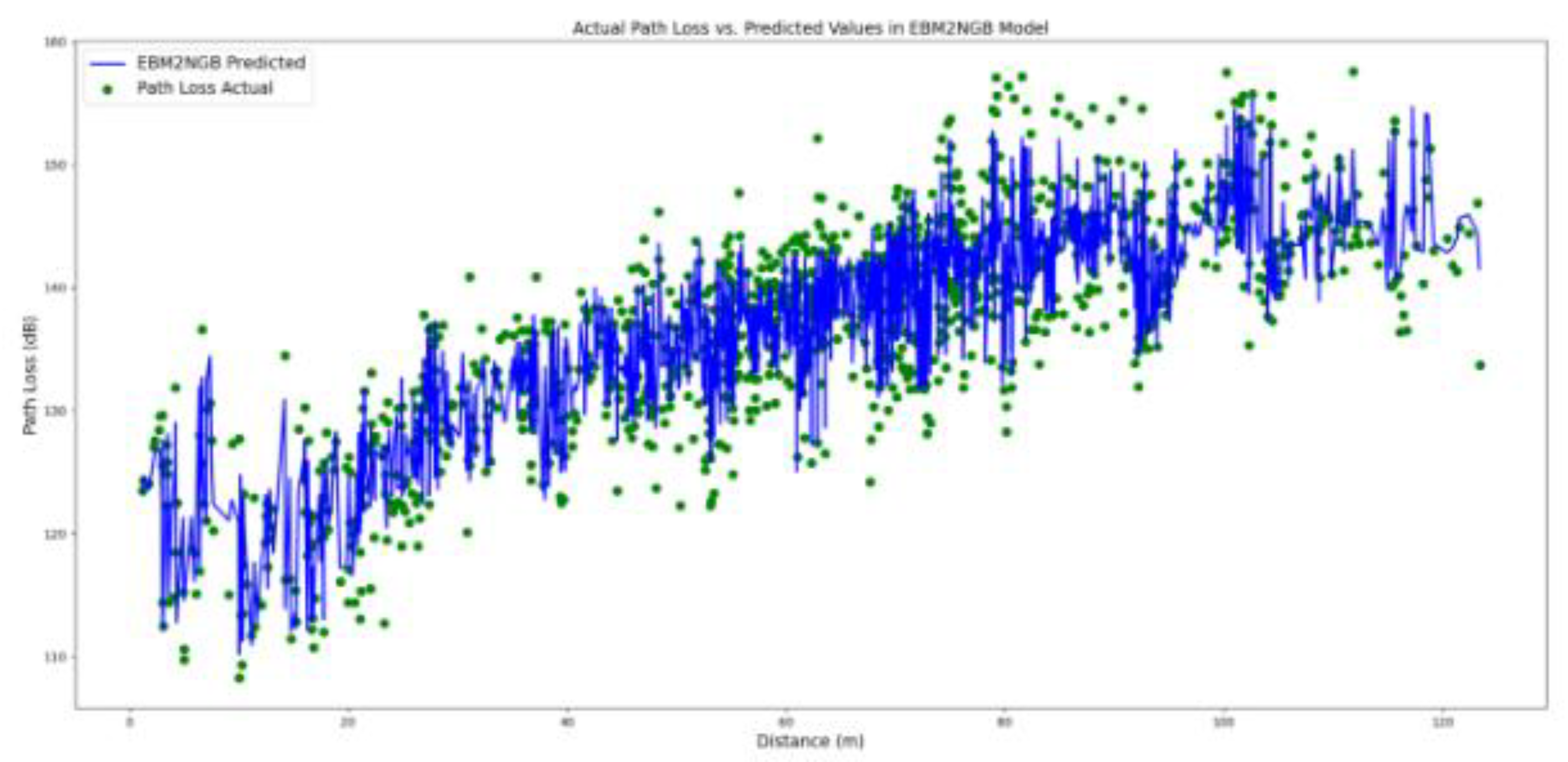

In comparison with the Bayesian LD model, the NGB model generate more accurate predictions while preserving the probabilistic nature of the predictions. However, as presented in Table 4, the delivered MAE, MAPE, and the RMSE metrics are slightly deteriorated. To integrate the probabilistic outcome of the NGB model with the more accurate EBM model, we further evaluate the probabilistic-informed ensemble EBM2NGB model on the hold-out dataset. As presented in Table 4 and illustrated in

Figure 8, the EBM2NGB model metrics are slightly improved in comparison to the EBM model.

Figure 7.

predicted values together with the lower and the upper 95% confidence interval in EBM2NGB Model.

Figure 7.

predicted values together with the lower and the upper 95% confidence interval in EBM2NGB Model.

Model Global Explanations

This section elaborates on the rationale behind the EBM and NGB models to generate their predictions. From a global explanation point of view, we explain how both ML models decide to generate predictions over the entire dataset. The EBM model is a self-explainable, which does not require a surrogate explanation due to its glass box nature. In contrast, the explanations for the decisions behind the NGB model are drawn via the SHAP analysis.

As the result of training, the intercept of the EBM model (the parameter in equation 15 and equation 16) in our study amounts 137.329 dB. Likewise, the intercept of the NGB-SHAP model (the parameter in equation 12), which is the PL mean values in the training dataset is equal to 137.340 dB. The intercept for the parameter (equation 10), which is an indicator for measuring the mean uncertainty of the model is equal to 1.218, which is associated with 3.380 dB.

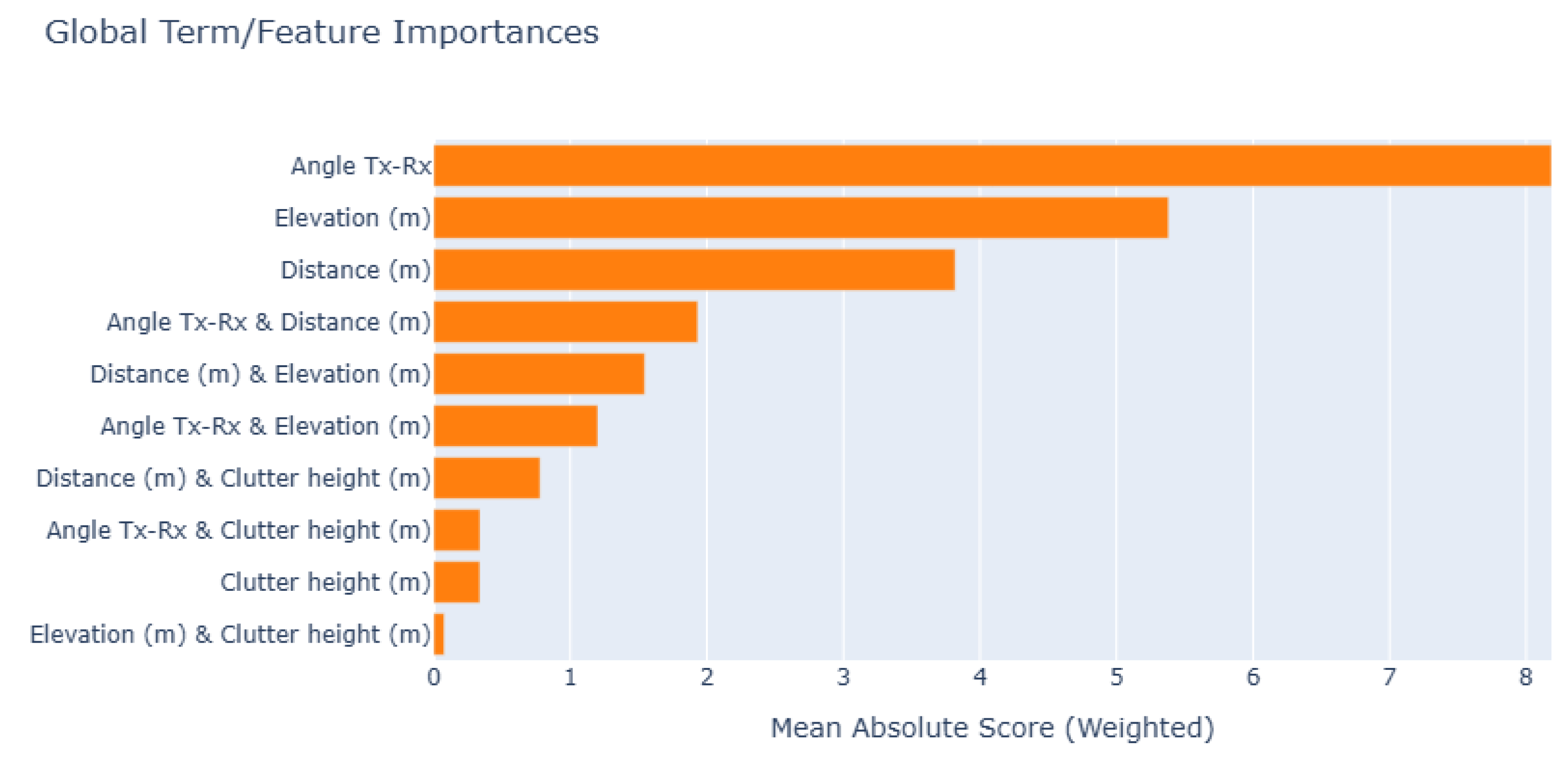

Figure 9 illustrates the average absolute additive (main and interactive) effect, which each feature in equation 16 can induce to change the outcome of the EBM model beyond the EBM model intercept. Hence, the values in

Figure 9 can be perceived as the Global expression of the features importance in the model predictions. Among all the features, the transmitter to receiver distance plays the most significant role in generating prediction. The interaction of the transmitter to receiver angle with distance, as well as the main individual effect of the transmitter to receiver angle, are the second and the third most important features globally contributing in PL predictions, respectively.

Figure 8.

Global Feature Importance in EBM Model.

Figure 8.

Global Feature Importance in EBM Model.

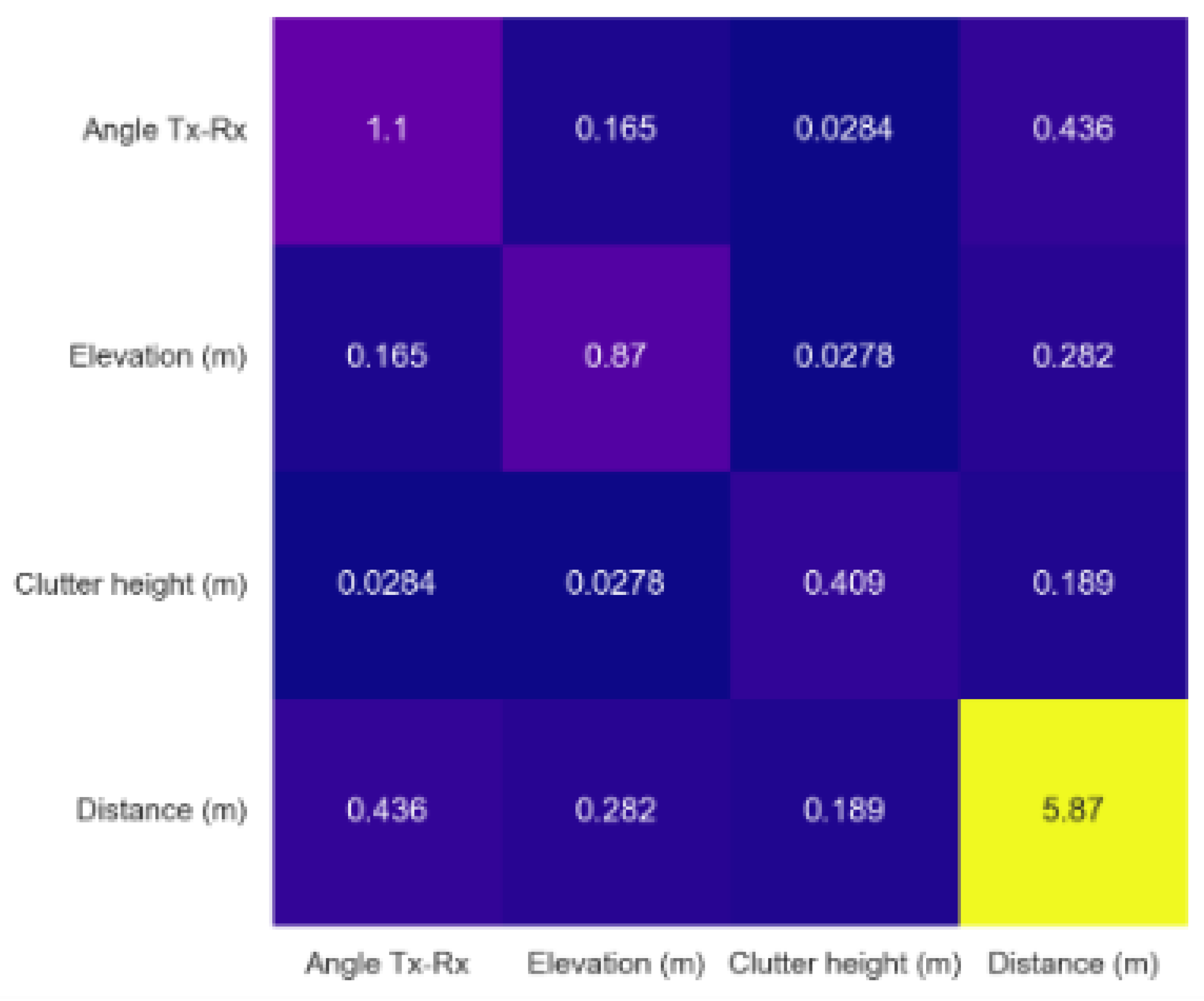

Figure 10 illustrates the average absolute additive (main and interactive) effect, that each feature in equation 16 can contribute to change the outcome of the NGB-SHAP model beyond the model’s intercept. In this figure, the values on the diagonal show the main features effect, and the other values show the SHAP interaction for pairs of features. Thereby, the main effect of the transmitter to receiver distance, the transmitter to receiver angle, and the elevation play the most important roles by contributing 5.87 dB, 1.1 dB, and 0.87 dB to the overall predictions, respectively. The interaction of the transmitter to receiver angle with distance is the next significant factor.

Figure 9.

Global Feature importance in NGB-SHAP Model.

Figure 9.

Global Feature importance in NGB-SHAP Model.

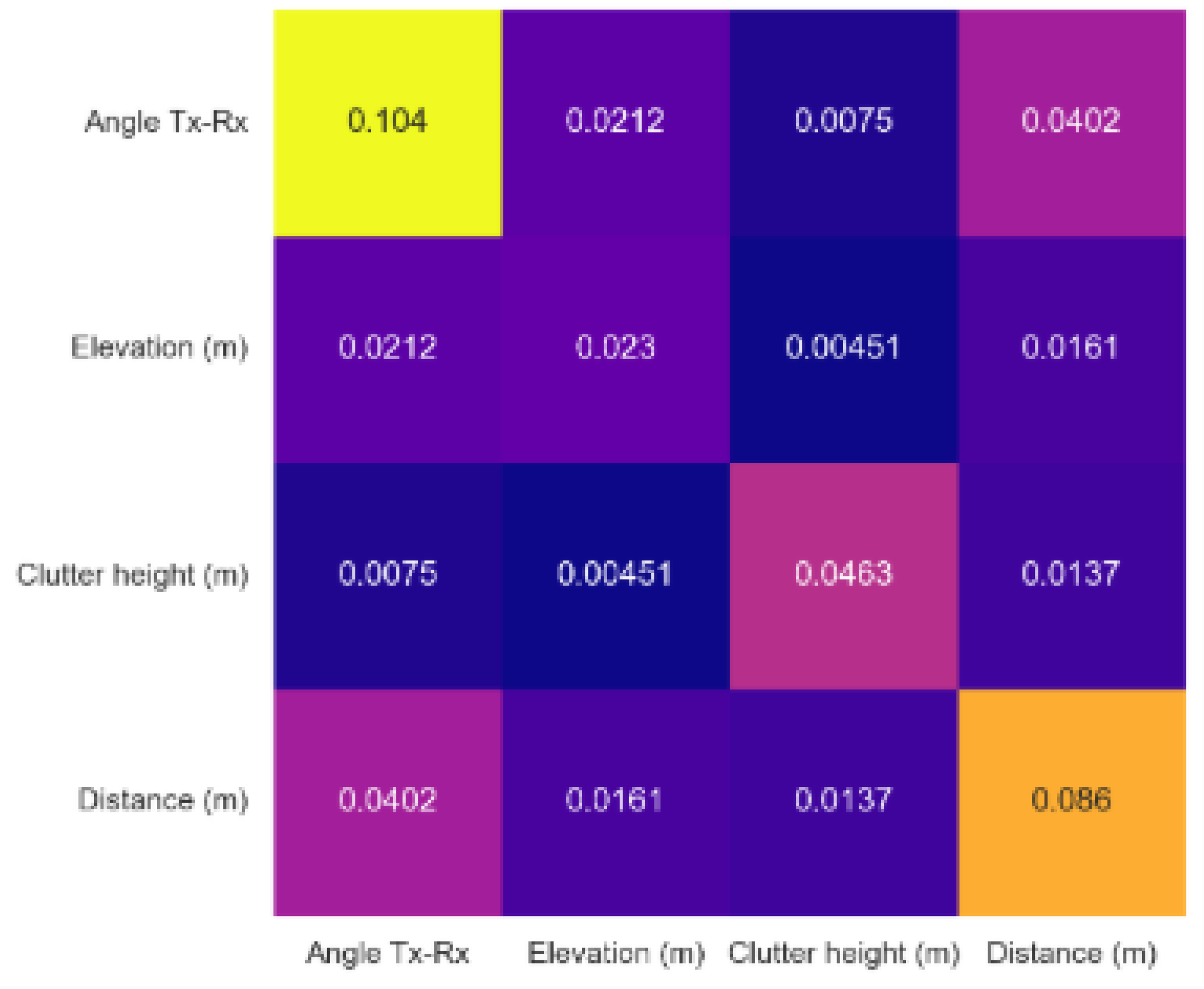

Figure 11 illustrates the average absolute additive (main and interactive) NGB-SHAP effects, with respect to the generated standard deviation in the NGB model. As shown in figure, the transmitter to receiver angle emerges as the main source of the uncertainty in NGB predictions. This phenomenon can be attributed to the directional antenna pattern in the study terrain, which likely divide the receiving points into separate signal coverage regimes within the vineyard.

Figure 10.

Global Feature importance for Uncertainty in NGB-SHAP Model.

Figure 10.

Global Feature importance for Uncertainty in NGB-SHAP Model.

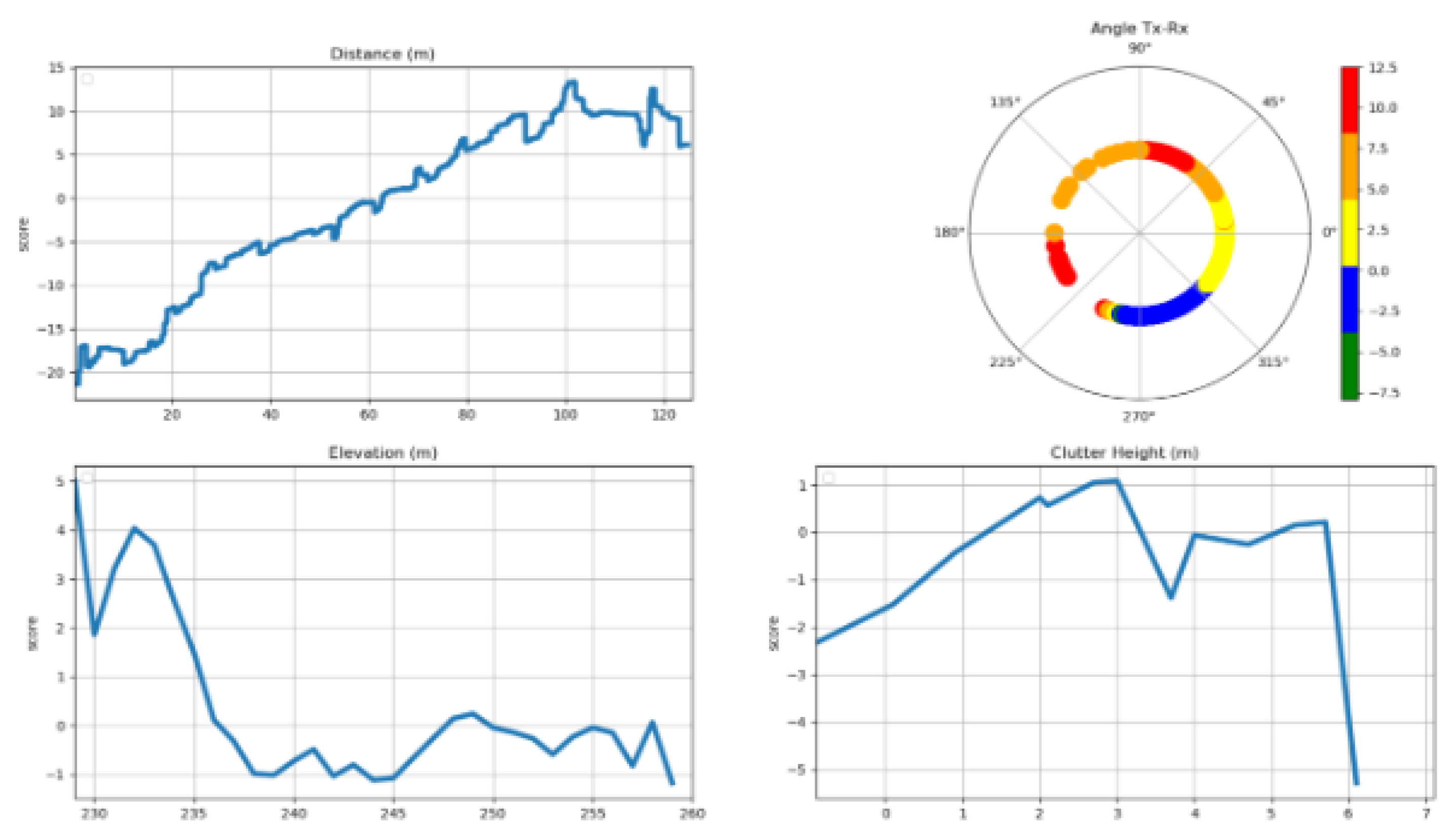

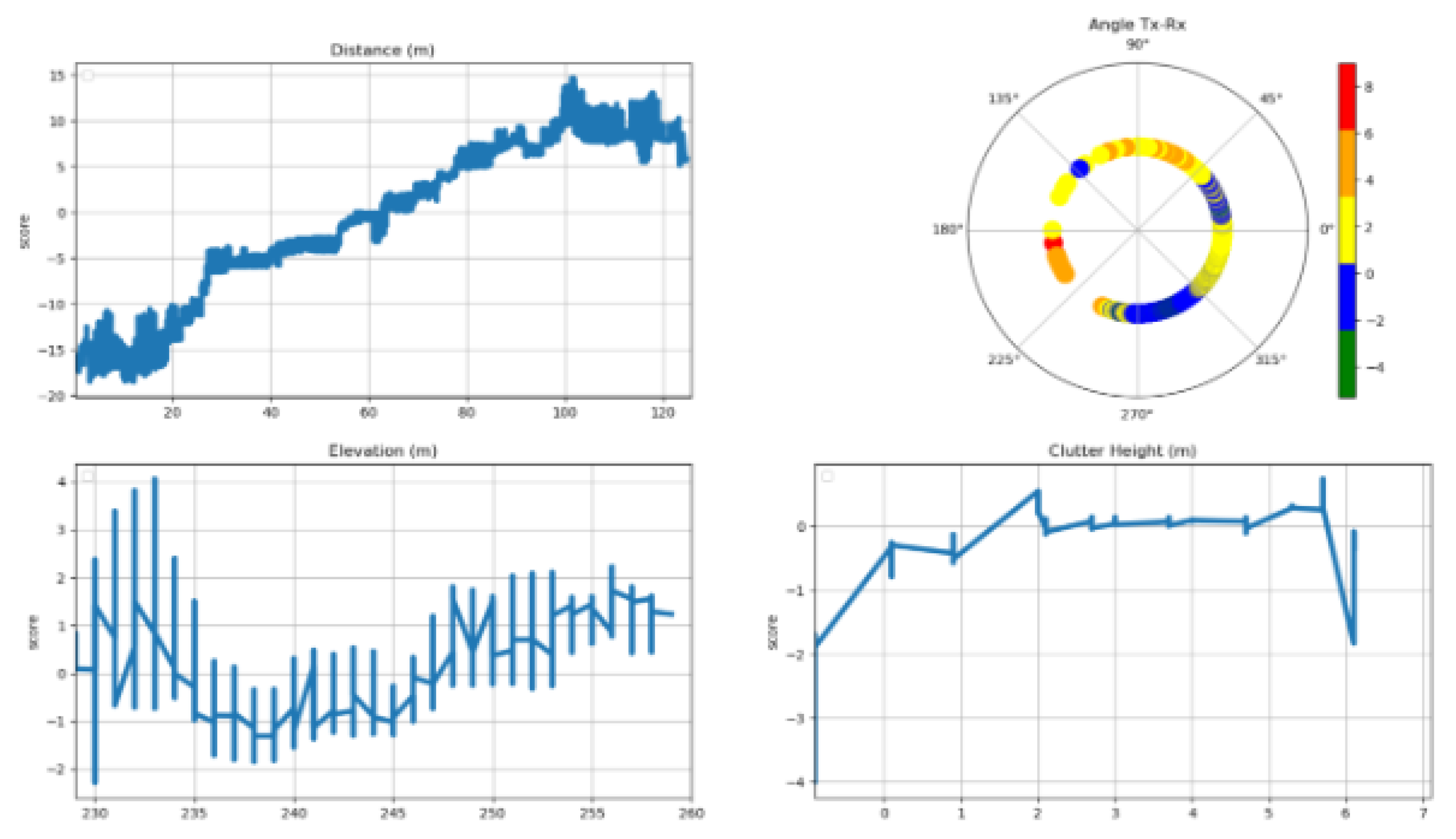

Figure 11 describes the features marginal contributions in the EBM model. Feature marginal contribution maps each possible value of an input feature to a corresponding contribution (in a look-up table manner) to generate PL predictions. The overall effect of the feature distance from the transmitter is shown in the upper left-hand panel in

Figure 11. The effect of the feature distance in the vineyard reveals a linear characteristic, with a 45-degree rise from the minimum distance up to around 100 m and then with some near to zero but fluctuating overall slope from that point onward.

The upper right-hand panel shows the overall effect of the feature transmitter to receiver angle. The center point in the upper right-hand panel of

Figure 11 represents the location of the transmitter. The ring around the center point represents the PL strengthening or weakening when it transmits from the base station towards a specific direction. The effect of the Tx-Rx angle on the path loss in our study terrain can be understood based on the directional antenna pattern. Especially, the receiver points located between 270

o and 315

o have the best chance of establishing a line of sight (LoS) link to the transmitter. In contrast, the receiver points located between 45

o and 225

o fall outside the antenna’s main coverage area.

The overall elevation’s effect is shown in the lower left-hand panel in

Figure 11. In general, higher elevations are associated with higher losses in received signal. However, this pattern becomes less consistent between elevations of approximately 245 meters and 260 m.

The overall effect of the feature clutter height (lower right-hand panel in

Figure 11) can be easily divided into two parts. For clutter heights up to 3 m, path loss tends to increase, for clutter higher than 3 m, path loss begins to decrease.

Figure 11.

Feature marginal contribution in EBM Model.

Figure 11.

Feature marginal contribution in EBM Model.

Figure 12 describes the features marginal contributions in the NGB-SHAP model. The sub-panels can be understood analogous to the sub-panels described in

Figure 11. Indeed, the overall patterns generated through the NGB-SHAP model comply to a large extent with those from the EBM. SHAP local explanations can generate different features marginal contributions values for the same feature value in each data point. This stochastic effect is reflected in the features marginal contributions in

Figure 12. In addition, while there are partial disagreements between the XAI generated based on the NGB-SHAP and the XAI generated based on the EBM mode. For example, the upper right-hand side of the

Figure 12 (based on the NGB-SHAP model) explains most of the receiver points located between 0

o and 45

o as the points having a chance to receive negative PL contributions from the transmitter to the receiver angle point of view. In contrast, the EBM based contribution (cf.

Figure 11) associate the same points with higher PL contributions. Additional trivial inconsistencies between the model explanation patterns can be seen by comparing each sub-panel in

Figure 11 with its corresponding counterpart in

Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Feature marginal contribution in NGB-SHAP Model.

Figure 12.

Feature marginal contribution in NGB-SHAP Model.

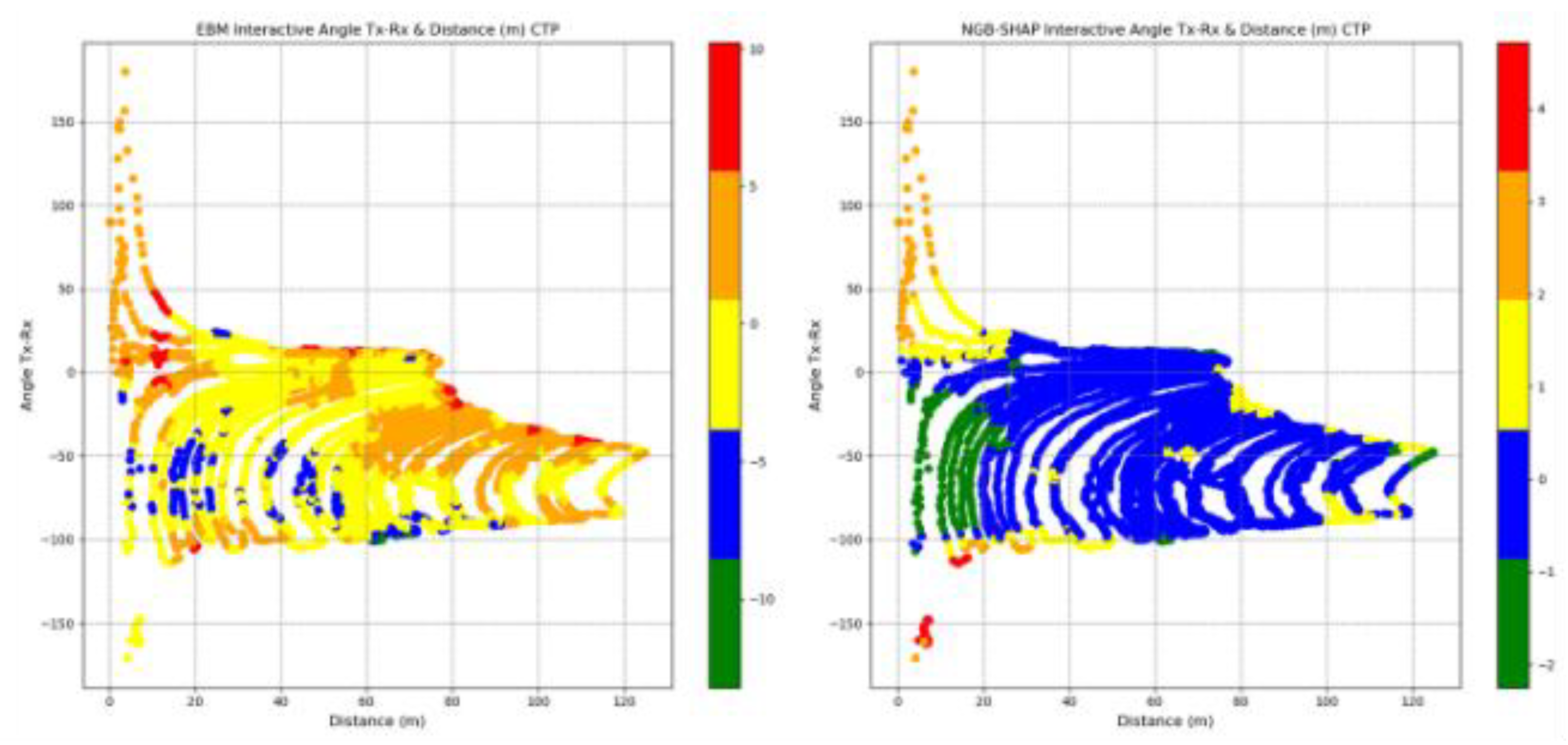

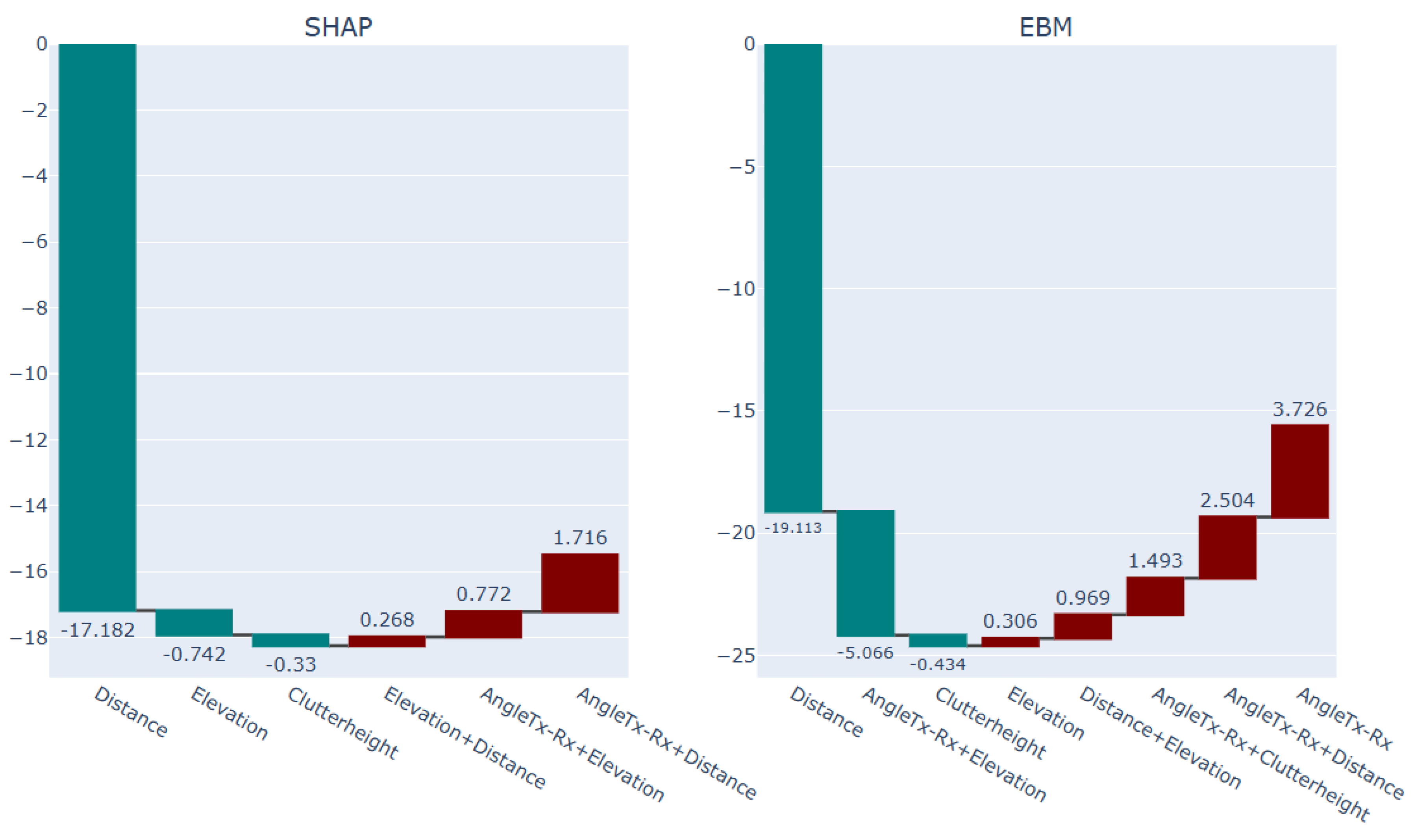

Figure 13 demonstrates the contribution of the interaction effects in the NGB-SHAP model (right-hand panel) and the EBM model (left-hand panel) explained by the equations 14 and 16, respectively. A thorough interpretation of bilateral feature interaction (as well as possible higher orders of interactions) would require a detailed spatial analysis of the area between the transmitter and the receiver, along with specific characteristics of the receiver location. Here, we focus on the interaction of distance and the Tx-Rx angle, which emerges as the most significant interaction in both models.

The mean absolute interaction effect between distance and Tx-Rx angle is approximately 2.5 dB in the EBM model and 0.5 dB in the NGB-SHAP model. In the right-hand side of the

Figure 13, the blue colored points are indicating on average near to zero contribution of the combination of the corresponding feature values in dB units to the NGB-SHAP model’s PL predictions. Green colored points, located within 0 to 20 meters from the transmitter and between transmitting angles 0

o to -100

o , exhibit negative contributions (i.e., reduced path loss) of up to -2 dB. The points outside the aforementioned angle are suffering from up to +4dB path loss.

In contrast, the trained EBM model identifies a subset of the receiver points located within 0 to 80 meter and transmission angle between -50o and -100o as benefitting from significant reductions in path loss, ranging from -5 dB to -10 dB. However, increasing the values of the distance within the transmitting angles higher than the -50o can cause high path loss effects ranging from +5dB to +10 dB. Analogous to the NGB-SHAP explanation, the EBM model reveals a distinct spatial zone comprising of points between 0 to 20 meters distance and outside the transmitting angle in-between the 0o to -100o suffering from up to 10dB path losses can be detected.

Figure 13.

Interactive Distance-Angle Feature marginal contribution in EBM and NGB-SHAP Models.

Figure 13.

Interactive Distance-Angle Feature marginal contribution in EBM and NGB-SHAP Models.

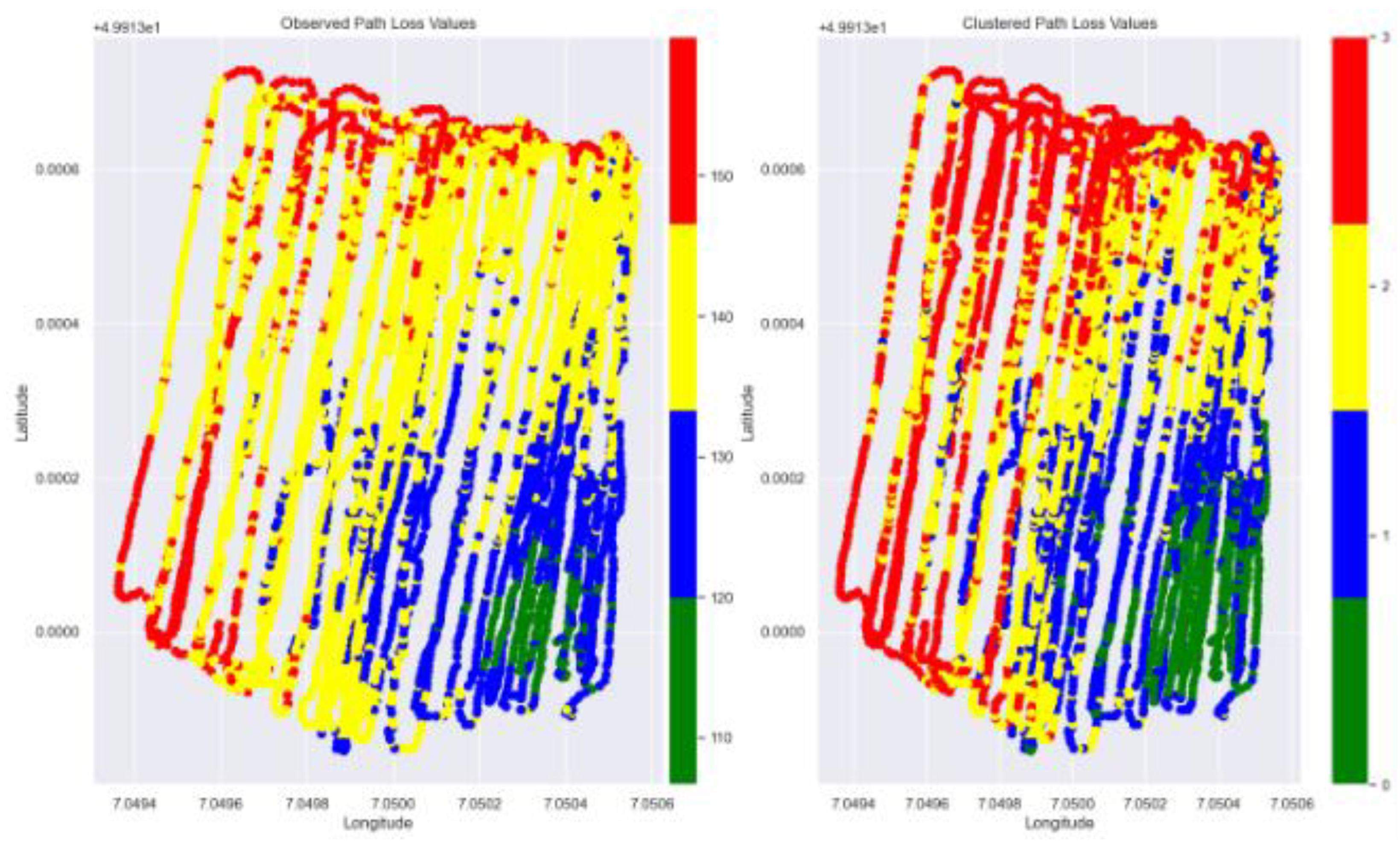

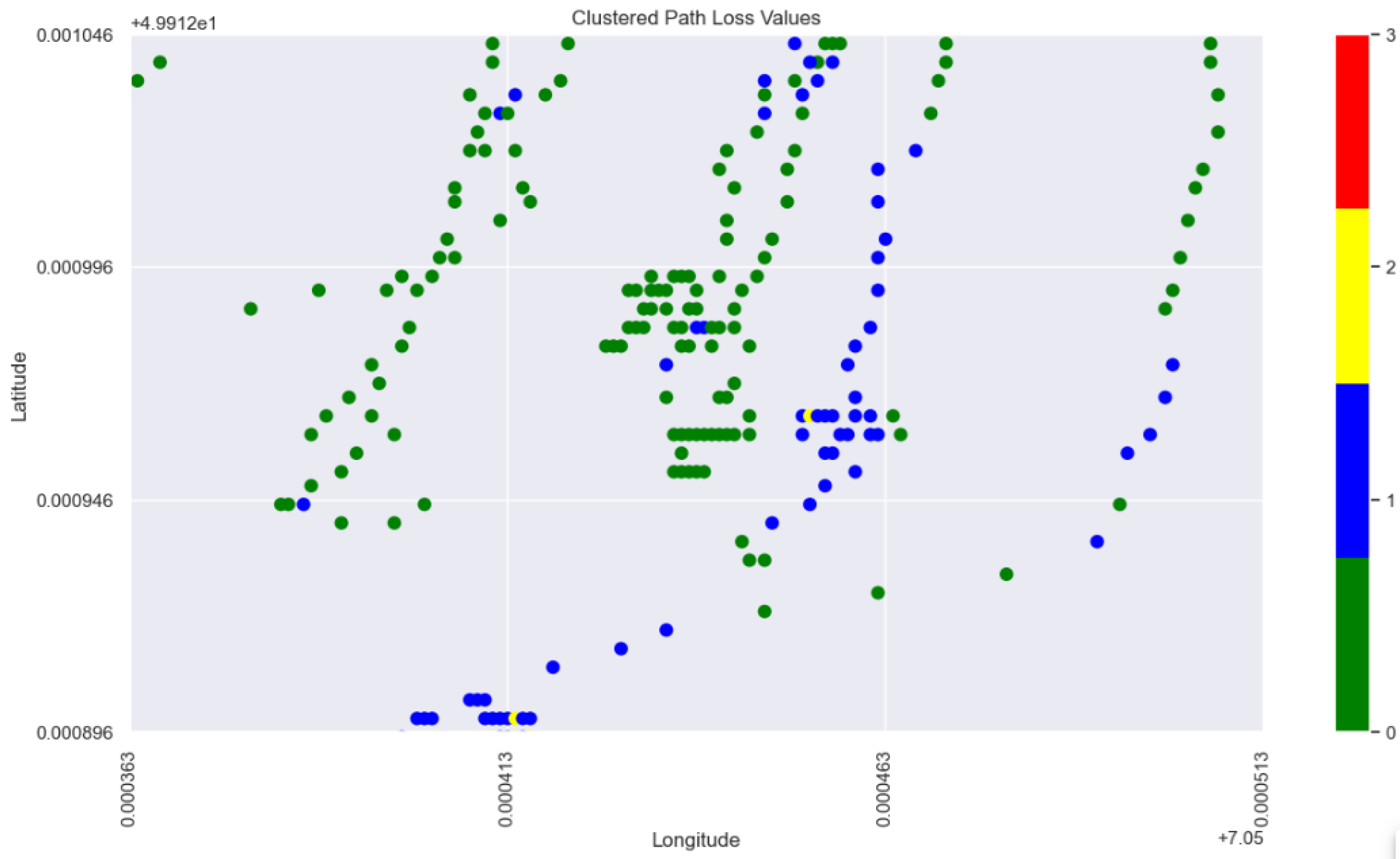

Model Local Explanations

Global XAI in the previous subsection sheds light on the overall importance of input features and the corresponding marginal contributions in the signal attenuation within our study terrain. However, there are questionable observations with regard to the behavior of path losses in specific locations of the terrain. These include, for example, abrupt changes in PL patterns at some points in the underlying study area or PL behavior deviating from the global XAI view within specific sub-area of the terrain. This necessitates more in-depth look at the reasons behind the ML model predictions at the local level. To support our local XAI analysis based on a consistent view of the terrain, we first apply K-Means clustering based on the spatial locations of data points (comprising longitude, latitude) linked to their corresponding Path Loss values. This serves to figure out intrinsic grouping of data points across the entire vineyard map. The optimal resulted number of clusters through applying the elbow method is

4. The resulting four clusters are visualized on the vineyard map in

Figure 14, with distinct colors distinct colors used to represent each cluster on the right hand panel. The left hand side panel in

Figure 14 is plotting the observed path loss values sorted by means of distinct colors. The observed path loss values map and the clustered path loss values map comply with each other. Inspecting the PL values corresponding to the points belonging to each of the 4 clusters detected by the K-Means clustering, shows a distinctive partitioning of the data points across the vineyard based on the PL values, in which the green, blue, yellow, and red cluster points Pl values in dB units are lying in the (min, max) ranges equal to (106.65, 125.95), (126.0 , 135.25), (135.3, 143.1), and (143.15, 159.9).

Figure 14.

Clustered PL values versus Measured PL values in the study terrain.

Figure 14.

Clustered PL values versus Measured PL values in the study terrain.

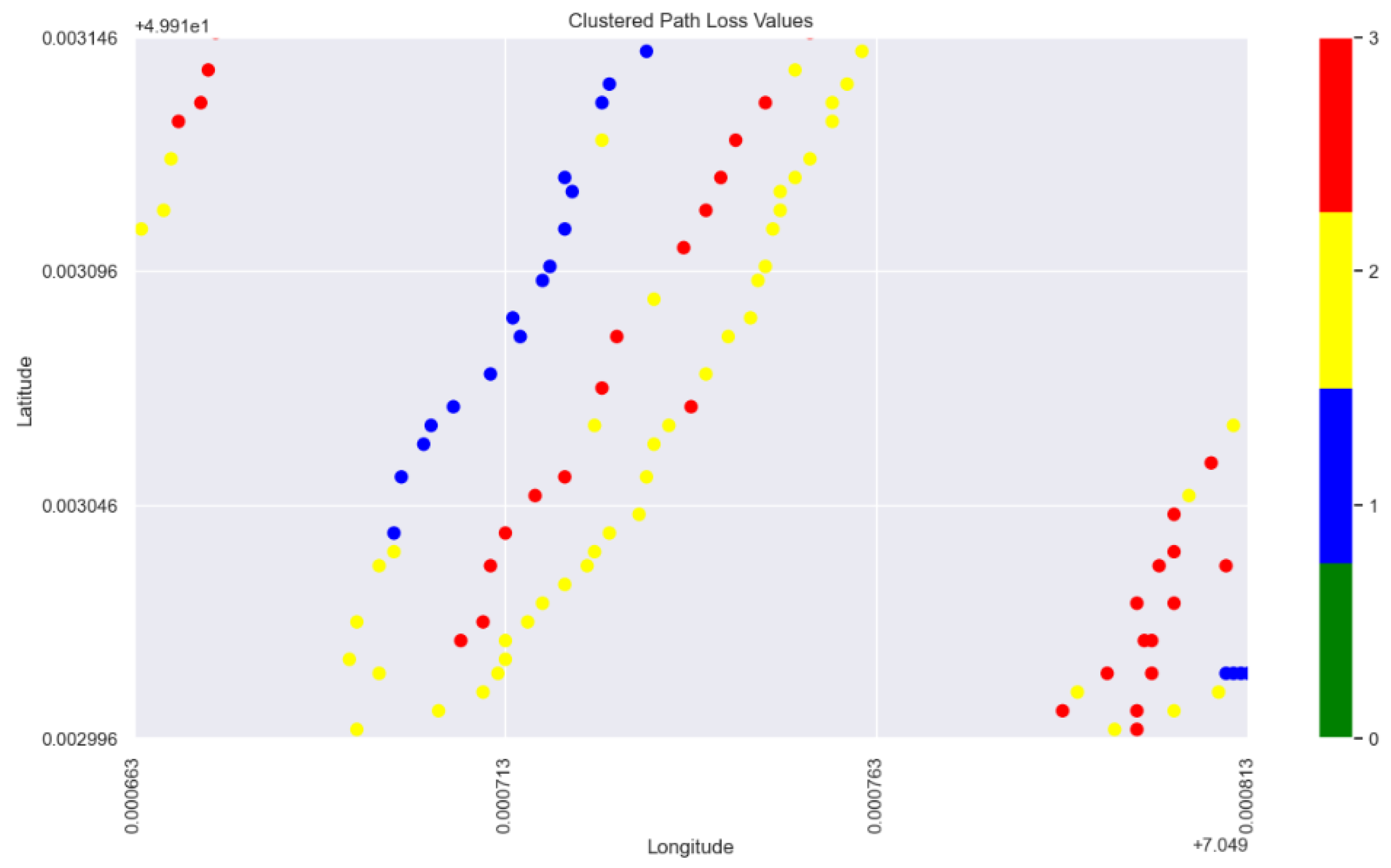

Two local sub areas of the terrain, presented in

Figure 18 and Figure 21, have been identified as regions showing deviating path loss behavior from the global XAI view and demonstrating abrupt changes in the path loss pattern, respectively. The square in the center of the

Figure 18 is encircling measured points with latitude and longitude in the (min, max) ranges equal to (49.913046, 49.913096) and (7.049713, 7.049763) , respectively. The points in this sub area are seemingly of similar geospatial profile in terms of distance and transmitting angle relative the base station. Though, the blue points are comprising less signal attenuation values even when the red points are slightly less distanced from the base station.

Figure 15.

Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (1).

Figure 15.

Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (1).

The difference between the red points data and the blue points data can be shown from an overview of the points profile, mean observed values as well as mean predicted values by ML models conveyed through the

Table 5.

Table 4.

overview of the red points data and the blue points profile.

Table 4.

overview of the red points data and the blue points profile.

| |

Count |

Mean

Angle Tx-Rx |

Mean

Elevation (m) |

Mean

Clutter height (m) |

Mean Distance (m) |

Mean Observed PL |

Mean EBM Predicted |

Mean NGB Predicted (mean, std) |

| Blue points |

3 |

-79.47 |

236.0 |

-0.89 |

80.82 |

133.55 |

133.78 |

(136.44, 4.96) |

| Red points |

5 |

-81.14 |

235.40 |

1.30 |

79.26 |

144.79 |

140.88 |

(140.13, 4.20) |

The difference between the interpretation of the blue points in contrast to the interpretation of the red points from the ML models can be seen in

Figure 19 and

Figure 20, respectively.

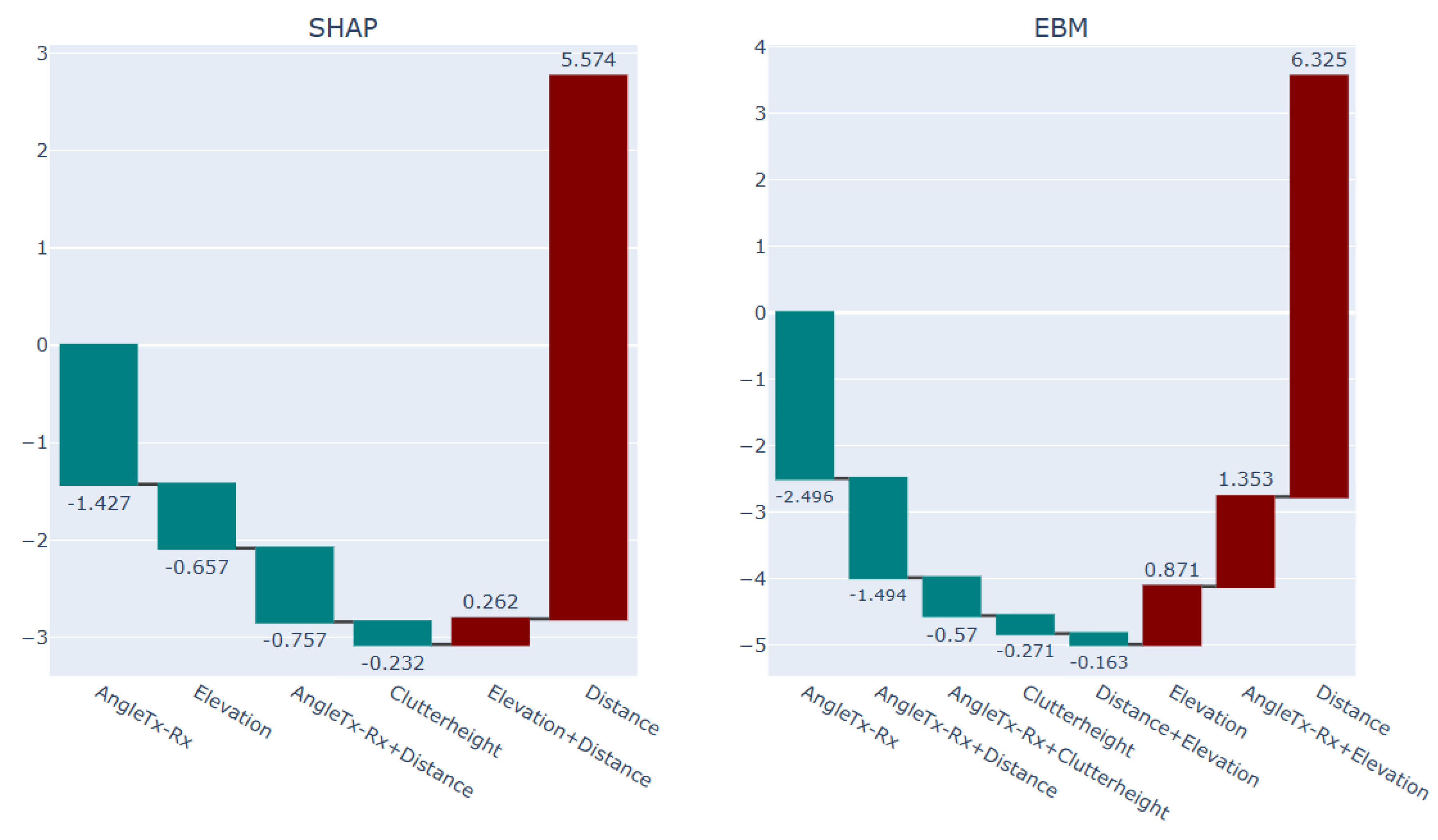

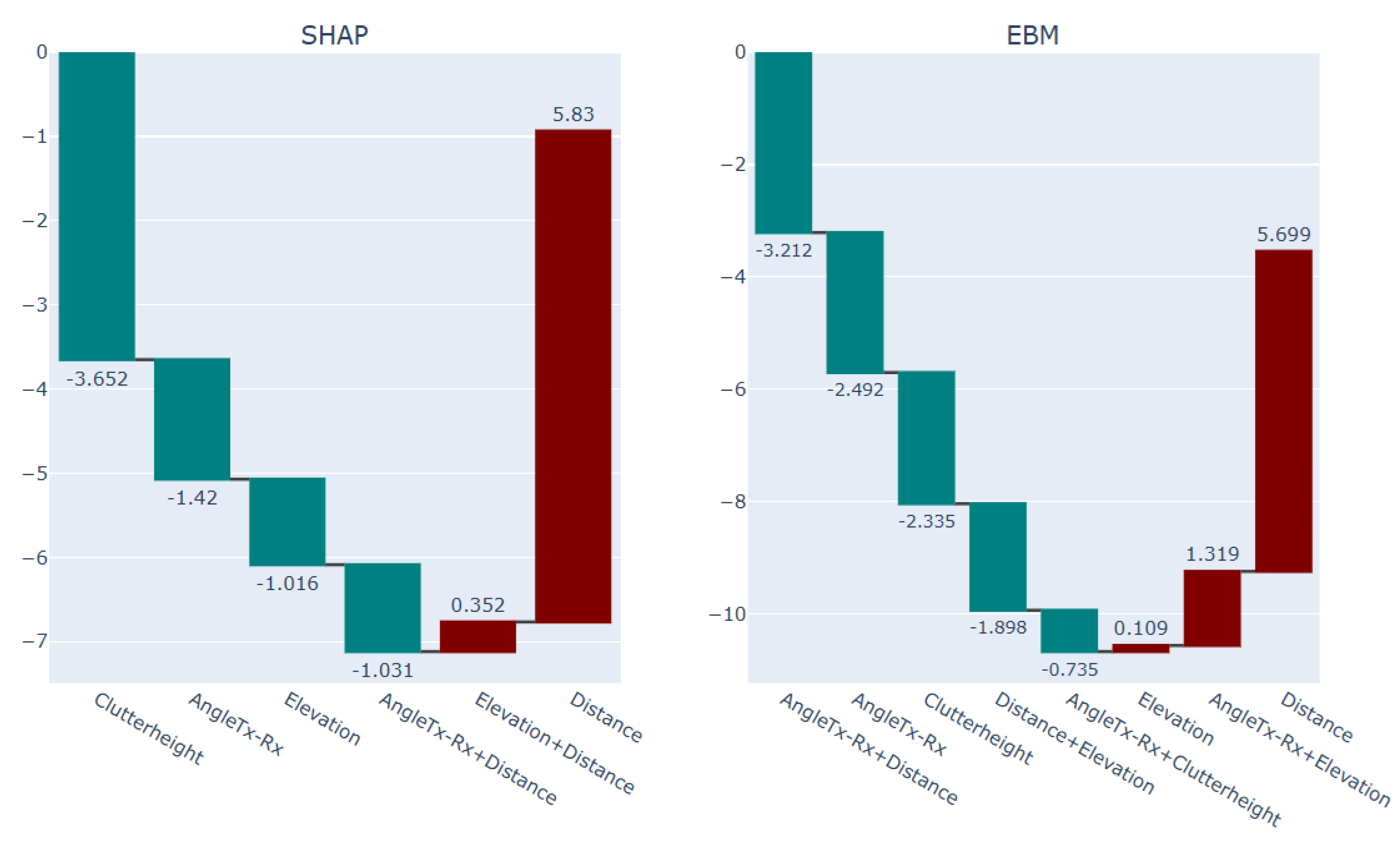

Figure 19 presents the the interpretation of the red points, featuring NGB-SHAP explanation on the left-hand side panel and the EBM explanation on the right-hand side panel. Similarly,

Figure 20 provides the interpretation of the blue points, again NGB-SHAP explanation on the left-hand side panel and the EBM explanation on the right-hand side panel.

In both figures, presented bars are describing the amount of change in the model output beyond the model intercepts (for NGB-SHAP) and (for EBM ), as defined in equations 12 and equation 16, respectively. Teal coloured bars denote features that contribute to a decrease in the PL values. The decreasing effects are sorted based on their importance from left to the right. In contrast, the maroon colored bars denote features that contribute to an increase in predicted PL values. The increasing effects are sorted based on their importance from right to the left.

Comparing the explanation of the red points and the explanation of the blue points via the EBM and NGB-SHAP explanations in

Figure 19 and

Figure 20, shows how the decreasing impact of the factor clutter height as the foremost decreasing factor and the third most decreasing factor in the NGB-SHAP model and the EBM model, respectively, changes the balance of the influencing forces to come up with lower path loss values by the blue points. The decreasing effect of the factor clutter height on decreasing the PL values can be checked with reference to the lower right-hand side panels in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

Figure 16.

Explanation of the blue points Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (1) via SHAP and EBM models.

Figure 16.

Explanation of the blue points Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (1) via SHAP and EBM models.

Figure 17.

Explanation of the red points Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (1) via SHAP and EBM models.

Figure 17.

Explanation of the red points Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (1) via SHAP and EBM models.

Figure 21 is comprising the next investigated sub-region in our study in terms of application of local XAI. The square in the center of the Figure 21 is entailing measured points with latitude and longitude in the (min, max) ranges equal to (49.912496, 49.912996) and (7.050413, 7.050463) , respectively. The points in this sub area are seemingly of similar geospatial profile with regard to their proximity to the base station. Though, the blue points are comprising higher signal attenuation values even when they are lying next to the base station (with 3.08 meter distance on average from Tx).

Figure 18.

Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (2).

Figure 18.

Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (2).

The difference between the green points data and the blue points data can be shown from an overview of the points profile, mean observed values as well as the mean predicted values by ML models conveyed through the Table 6.

Table 5.

overview of the green points data and the blue points profile.

Table 5.

overview of the green points data and the blue points profile.

| |

Count |

Mean

Angle Tx-Rx |

Mean

Elevation (m) |

Mean

Clutter height (m) |

Mean Distance (m) |

Mean Observed PL |

Mean EBM Predicted |

Mean NGB Predicted (mean, std) |

| Green points |

55 |

17.99 |

236.12 |

0.89 |

2.80 |

121.00 |

121.71 |

(121.98, 2.82) |

| Blue points |

23 |

56.84 |

235.56 |

0.89

|

3.08 |

128.13 |

127.03 |

(126.27, 2.81) |

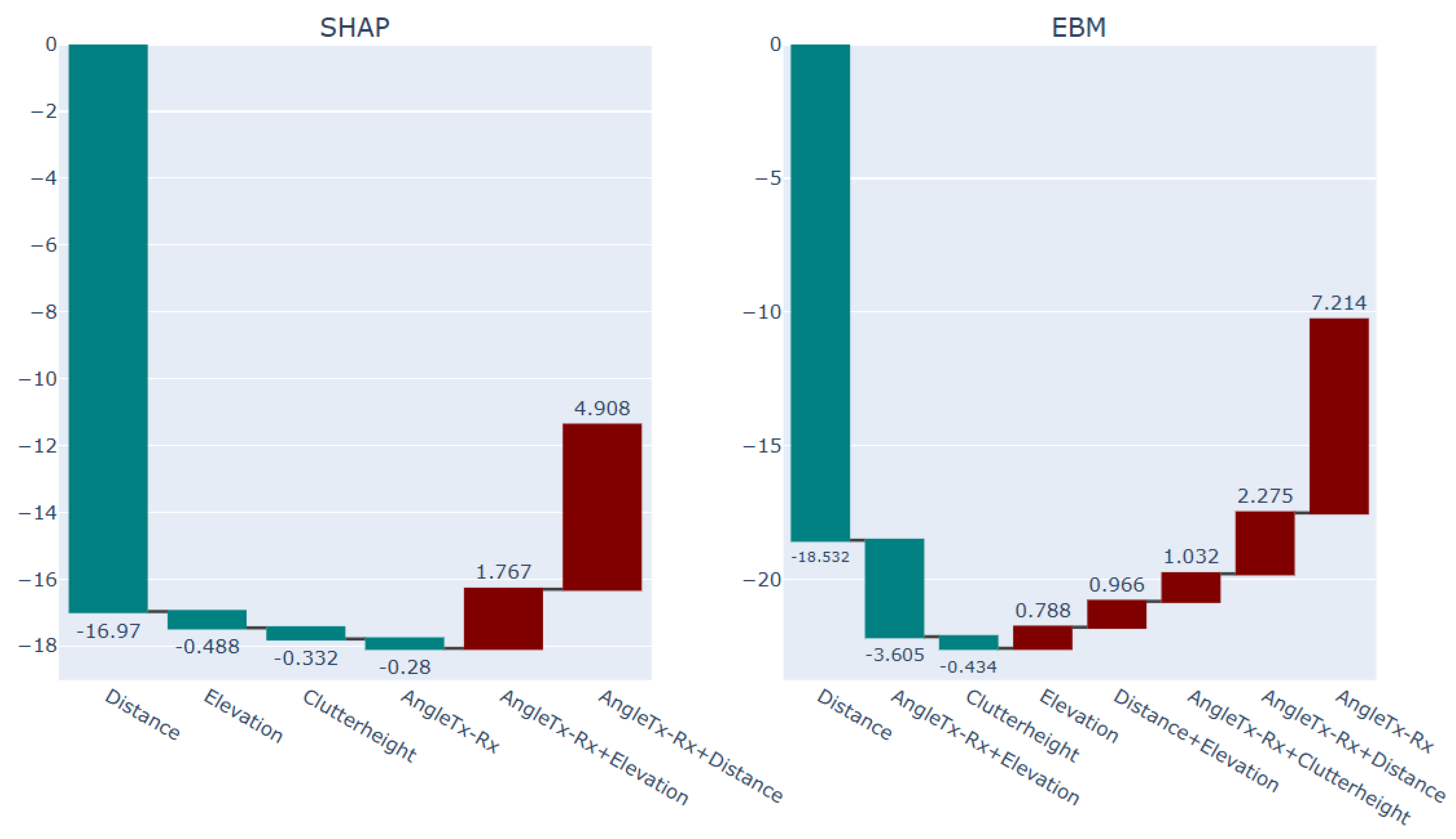

Comparing the explanation of the blue points and the explanation of the green points via the EBM and NGB-SHAP explanations in Figure 22 and Figure 23, shows how the increasing impact of the factor transmitting angle as the foremost increasing factor both in the NGB-SHAP model and the EBM model, respectively, changes the balance of the influencing forces to come up with higher path loss values by the blue points. The difference between effect of the transmitting angle being 56.84 degree and 17.99 degree on increasing and decreasing the PL values, respectively, can be checked with reference to the upper right-hand side panels in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

Figure 19.

Explanation of the blue points Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (2) via SHAP and EBM models.

Figure 19.

Explanation of the blue points Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (2) via SHAP and EBM models.

Figure 20.

Explanation of the green points Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (2) via SHAP and EBM models.

Figure 20.

Explanation of the green points Selected sub-area in the terrain with abruptive PL behavior (2) via SHAP and EBM models.