1. Introduction

Adult spinal deformity (ASD) is a common spinal disorder that is projected to become increasingly prevalent in the future [

1]. ASD may be brought about by multiple etiologies, including degenerative disease, iatrogenic causes (e.g. prior spinal surgery), or conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis [

2]. Regardless of the cause, ASD often must be addressed via long-segment posterior pedicle screw and rod constructs. These surgeries can be quite effective in restoring proper alignment and promoting adequate fusion. However, extensive rigid constructs also carry the risk of complications, notably proximal junctional kyphosis (PJK), broadly defined as kyphosis that develops at the interface of the cranial end of the construct and the adjacent mobile segments [

1,

3,

4]. The prevalence of PJK after surgery for ASD may lie between 20-40%, though some sources report rates as high as 61% [

5,

6,

7,

8].

While a global definition of PJK is consistent among publications, various authors have put forth different nuanced criteria [

3,

5,

9,

10]. In general, PJK is usually defined as an excess PJK angle, a Cobb angle formed between the upper-instrumented vertebra (UIV) and a supra-adjacent vertebra (SAV) either one (UIV+1) or two (UIV+2) vertebral levels above the UIV. Depending on the study, a Cobb angle of at least 10-20 degrees is required for the diagnosis of PJK [

3,

5,

9,

10]. Different cutoff values for PJK angle have been analyzed with respect to their prognostic value as predictors of postoperative pain, functional recovery, or need for revision surgery [

11,

12,

13]. Nonetheless, the results have not supported one strict definition of clinically significant PJK and no expert consensus currently exists as to the ideal magnitude to use for the PJK angle or which SAV should be used.

To that end, we used a large cohort of patients >65 years of age who underwent thoracolumbar fusions for ASD to better characterize the variance and overlap among multiple existing definitions of PJK used in the literature and to evaluate which definitions may be the most useful to compare across future studies.

2. Materials and Methods

Radiographic and demographic data were collected for thoracolumbar fusion from an institutional database for patients

>65 years old with a diagnosis of ASD. Patients who underwent fusion of at least three segments within the thoracolumbar region with pelvic fixation at the authors’ institution between 2014-2024 were included, while patients with missing radiographs for required analysis were excluded. Preoperative and most recent follow-up (

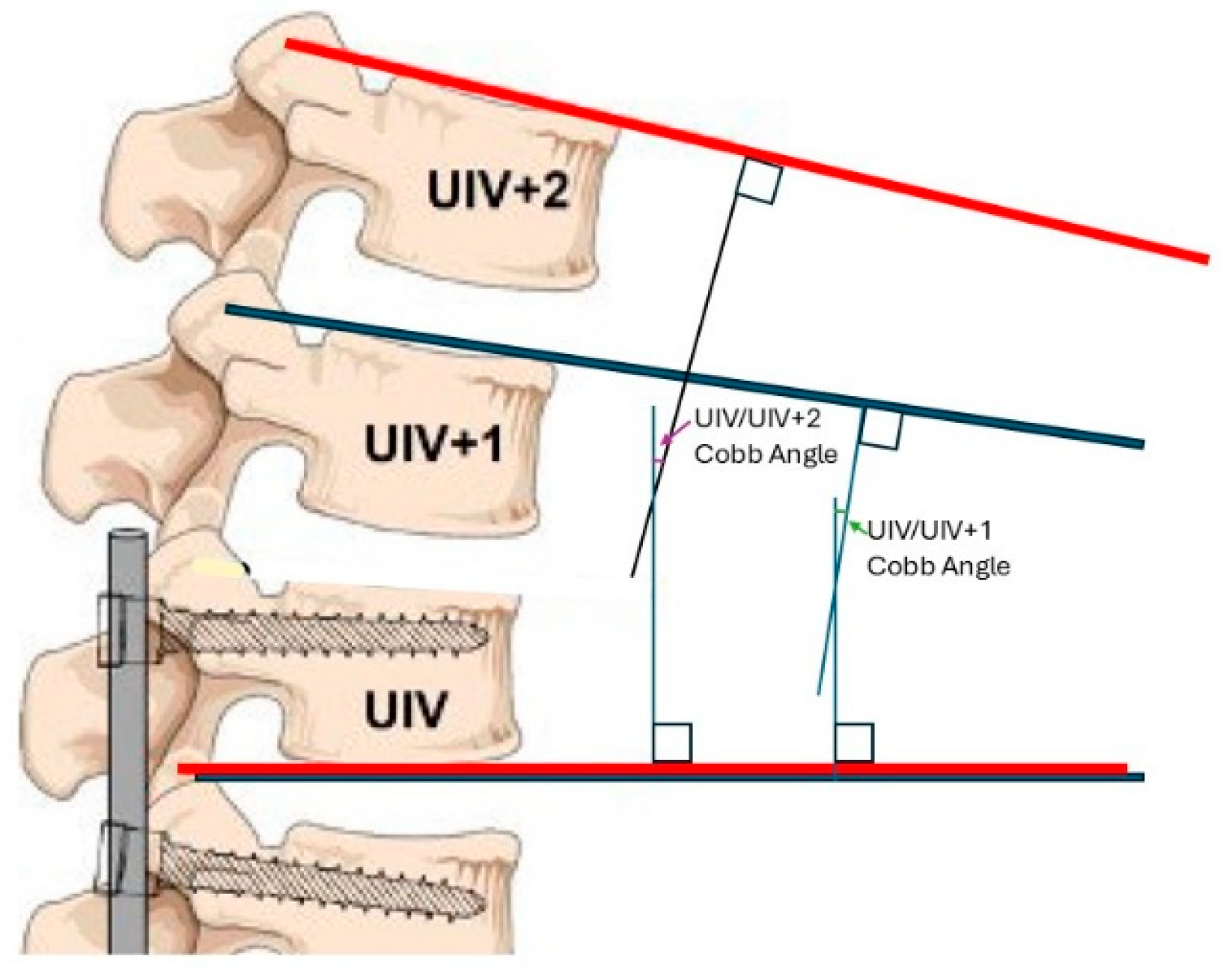

>6 months postoperative) full-body scoliosis radiographs were exported from the patient’s electronic medical record (EMR). The upper instrumented vertebrae (UIV) for each patient were identified from intraoperative/postoperative imaging, and the Cobb angle was measured between the inferior endplate of the UIV and the superior endplate of the vertebrae immediately cranial to the UIV (UIV+1) (

Figure 1, blue). A second Cobb angle was measured between the inferior endplate of the UIV and the superior endplate of the vertebrae two levels cranial to the UIV (UIV+2) (

Figure 1, red) [

14]. Angles were measured from both the preoperative and most recent follow-up radiographs.

A PubMed search with key terms (“proximal junction* kyphosis” AND “definition”) and subsequent exploration of citations yielded 6 criteria for varying definitions of PJK based on different thresholds of the UIV to UIV+1 or UIV+2 cobb angle [

3,

5,

9,

10,

15,

16]. A series of statistical tests were performed with R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing version 4.4.1 (CRAN, 2024). A Pearson’s Chi Squared test was performed among the different rates of PJK based on the definitions identified from the PubMed search. A subsequent pairwise comparison of proportions was performed to evaluate the distinctness of each individual definition’s rate in comparison to one another. Rate of agreement among PJK definitions were also analyzed in a pairwise fashion, followed by an evaluation of the proportion of PJK diagnoses that would also be diagnosed by additional criteria. Statistical significance was established by an alpha <0.05, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated.

3. Results

A total of 116 patients met inclusion criteria, 79 of whom were female (68.1%). The average age of the cohort was 70.9

+ 4.3 years, and the average BMI was 28.9

+ 5.4 (

Table 1). Analysis of PJK definitions requiring identification of the UIV+2 decreased the total cohort to 111 patients due to visual obstruction of the UIV+2 vertebrae from either image cutoff or low resolution for 5 patients. For consistency, analysis of all PJK definitions were performed among the 111 eligible patients.

The following 6 criteria for PJK were identified from the PubMed search: [

1] PJK angle

>20° with UIV+2 as the SAV; [

2] PJK angle

>10° with a >10° change from preoperative values with UIV+2 as the SAV; [

3] PJK angle >2 standard deviations from average with UIV+1 as the SAV; [

4] PJK angle

>10° with a >10° change from preoperative values with UIV+1 as the SAV; [

5] PJK angle >15° with UIV+1 as the SAV; and [

6] PJK angle >30° with UIV+2 as the SAV, displaced rod fracture, or reoperation within 2 years for junctional failure, pseudoarthrosis, or rod fracture (

Table 2) [

3,

5,

9,

10,

16]. These PJK definitions will henceforth be referred to as [

1]

PJK20, [

2]

PJK10, [

3]

PJK2SD, [

4]

PJK10+10, [

5]

PJK15, and [

6]

PJK30. PJK rates, by each definition, were 1) 20.7% (95% CI: 13.8-29.7%), 2) 36.9% (95% CI: 28.1-46.7%), 3) 3.6% (95% CI: 1.2-9.5%), 4) 23.4% (95% CI: 16.1-32.6%), 5) 15.3% (95% CI: 9.4-23.7%), and 6) 10.8% (95% CI: 6.0-18.5%).

Pearson Chi-Squared testing revealed significant variance among rates of PJK by criteria (p=2.6*10

-9, χ2=48.7, 95% CI: 0.83-12.8) with a Cramer’s V of 0.27 (95% CI: 0.18-0.34). Post-hoc pairwise proportion testing with Holm p-value adjustment revealed 5 significantly distinct definition pairs and 10 non-significantly distinct pairs. The distinct pairs were

PJK20&

PJK2SD (p=2.63*10

-3, 95% CI: 0.088-0.25),

PJK10&

PJK2SD (p=4.86*10

-3, 95% CI: 0.24-0.43),

PJK10&

PJK15 (p=2.80*10

-8, 95% CI: 0.10-0.33),

PJK10&

PJK30 (p=1.50*10

-4, 95% CI: 0.15-0.37), and

PJK2SD&

PJK10+10 (p=4.90*10

-4, 95% CI: 0.11-0.28) (

Table 3). In other words, the overall PJK rates for our cohort given by these distinct pairs were significantly different from each other. Meanwhile the overall PJK rates given by every other pair were not significantly different.

The pairwise agreements of the cohort classification as PJK positive or negative among these six definitions are shown in

Table 4. These percentages represented the proportion of patients that were similarly diagnosed as having or not having PJK between the pair of definitions. The pairs with greatest agreement were

PJK10+10&

PJK15 at 90.1% (95% CI: 82.6-94.7%),

PJK2SD&

PJK30 at 89.2% (95% CI: 81.5-94.0%), and

PJK2SD&

PJK15 at 88.3% (95% CI: 80.5-93.4%) (

Table 4). Furthermore,

PJK30,

PJK2SD, and

PJK15 had the greatest agreement with reoperation at 82.9% (95% CI: 74.3-89.1%), 79.3% (95% CI: 70.3-86.2%), and 71.2% (95% CI: 61.7-79.2%) respectively.

Among patients with PJK according to a particular definition, the following percentages were identified as having PJK by at least one other definition:

PJK20) 91.3%,

PJK10) 78.0%,

PJK2SD) 100%,

PJK10+10) 88.5%,

PJK15) 100%,

PJK30) 29.4%. The percentages of each definition’s PJK cohort that met criteria for additional PJK definitions are shown in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

Discussions of PJK are of much interest in spinal deformity literature. However, this condition is heterogeneously defined depending on the article and classification criteria used. In this study we used a large cohort of patients who underwent surgical correction of ASD to evaluate 6 different definitions of PJK identified in the current literature. We investigated which definition may encapsulate the most patients in our cohort to determine the definition that may be of most utility when comparing PJK among studies or for potential surgical decision-making. While we found that certain definitions of PJK captured similar patient subsets of our overall patient cohort, there were nevertheless significant differences between multiple criteria as to which patients would qualify as having PJK. In aggregate, our work demonstrates that comparison of results between studies that utilize distinct definitions of PJK may be difficult to interpret and of limited utility.

Only PJK definition

PJK30 directly considered patient outcomes beyond imaging findings by integrating the need for reoperation or instrumentation failure [

16]. Hence, we considered it the most clinically relevant definition for a symptomatic PJK.

PJK30’s close relationship with patient function and greatest agreement with reoperation rates supported its use as a pseudo- “gold standard” for comparison with other definitions (

Table 4).

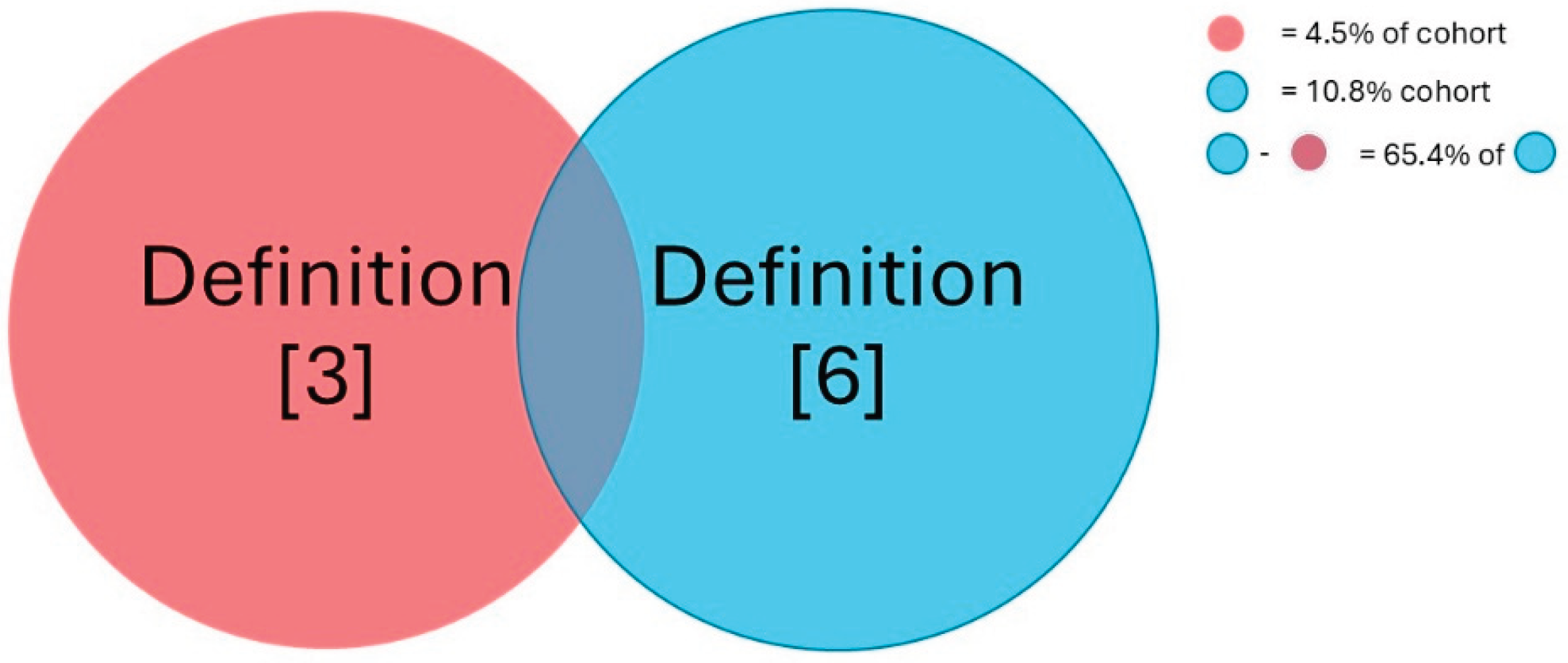

Considering the raw rate of PJK-positive patients in the same cohort, definition

PJK2SD was the strictest for assigning PJK, while definition

PJK10 was the most lenient among the six PJK definitions. The low rate of PJK for definition

PJK2SD suggests that the dispersion of UIV/UIV+1 angles was functionally small to yield such a stringent diagnosis [

9]. Notably, the tightness of distribution of this UIV/UIV+1 angle was relatively more extreme than the already conservative gold-standard of definition

PJK30. This means that in contrast to clinically relevant definition

PJK30 (diagnosing 10.8% of the entire cohort), only 4.5% of the entire cohort experienced the kyphotic angle at the UIV varying outside expected ranges per definition

PJK2SD. A conservative calculation, assuming all 4.5% PJK patients per definition

PJK2SD were also accounted for by definition

PJK30, found that 58.3% of patients who experienced symptomatic PJK by definition

PJK30 did not meet the threshold for definition

PJK2SD. Considering that only 89.2% of positive or negative PJK diagnoses from definitions

PJK2SD and

PJK30 overlapped (

Table 4), 65.4% of patients with symptomatic PJK (qualified by definition

PJK30) were not accounted for by definition

PJK2SD (

Figure 2). It should be noted that definition

PJK2SD was historically applied to adolescent scoliosis, which features a distinctly different clinical, biomechanical, and pathophysiologic picture than the degenerative ASD featured in our cohort [

17].

A comparison of raw PJK rates from definitions

PJK10 and

PJK10+10, which differ only by usage of the UIV+1 or UIV+2 vertebrae as the cranial vertebrae in Cobb angle measurements, demonstrates that use of definition

PJK10+10, and thus the UIV+1 vertebrae, results in stricter criteria for PJK (

Table 2) [

3,

10]. Again, if we were to use definition

PJK30 as the standard for symptomatic PJK, use of definition

PJK10, or the UIV+2 vertebrae, could be interpreted as too lenient of a definition in comparison to use of definition

PJK10+10, or UIV+1.

Closer evaluation of the pairwise overlap between definition

PJK30 and either definitions

PJK10 or

PJK10+10 confirms that definition

PJK10+10, or use of the UIV+2, also diagnoses the PJK status of individual patients more similarly to that of definition

PJK30 (

Table 4). In fact, definition

PJK10 had the least overlap with definition

PJK30 compared to all other definitions, whereas definition

PJK2SD, which used extreme deviations of PJK from average values, had the best overlap. This might suggest that while definition

PJK2SD is the strictest criteria for PJK, those who met the high threshold to be considered PJK positive by

PJK2SD were more likely to require reoperation. However, definition

PJK30 also includes a criterion for extreme PJK angle magnitude, which may confound this conclusion.

Chi-square testing with post-hoc pairwise proportions analysis and p-value adjustment demonstrated that 10/15 (67%) definition pairs were not significantly different when evaluating overall cohort PJK rates (

Table 3). Among the 5 distinct pairs, definitions

PJK10 and

PJK2SD were most common. Definition

PJK10 was found to be too lenient and definition

PJK2SD too strict based on raw PJK rates, which could explain why they was often statistically different from the other definitions and limited in practicality. Definitions

PJK20,

PJK10+10,

PJK15, and

PJK30 were not distinct from each other. These results suggest that definitions

PJK10 and

PJK2SD should be used with caution when consistency across studies is desired, while definitions

PJK20,

PJK10+10,

PJK15, and

PJK30 may be used more interchangeably.

From the evaluation of additional PJK criteria that were encompassed by each of the 6 definitions, as shown in

Table 5, patients diagnosed as having PJK by definition

PJK2SD would also be sufficiently diagnosed by most other definitions. In the context of definition

PJK2SD’s stringent nature, this suggests that most other PJK definitions have sufficient coverage and that use of definition

PJK2SD may be redundant. On the other end of the spectrum, the patients labeled PJK-positive by

PJK30 were often not diagnosed by other PJK criteria. This finding further supports the utility of definition

PJK30, including capturing unique information that is missed by the remaining PJK definitions.

Overall, our findings suggest that definition PJK15 most optimally balances the clinical relevance of definition PJK30 while not yielding statistically different rates of PJK in our cohort. Additionally, definition PJK15 utilizes the UIV+1 vertebrae, which found greater agreement with definition PJK30 than when measuring the UIV+2 vertebrae. Definition PJK15 may also identify earlier PJK than definition PJK30 because PJK15, which relies purely on imaging characteristics, is not contingent on the patient undergoing reoperation, allowing clinicians to identify early PJK that may not have yet progressed to such a degree to necessitate surgical intervention.

5. Limitations and Future Steps

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design inherently limits its ability to establish causal relationships between the definitions of PJK and outcomes such as reoperation rates. Secondly, data collection was performed at a single institution, which may reduce generalizability of our findings to broader populations. Third, the exclusive focus on patients aged 65 and older may not reflect PJK dynamics in younger cohorts undergoing spinal surgeries. Another limitation is the study’s reliance on reoperation as a proxy for clinical outcomes. Other important measures such as patient reported pain, functional recovery and quality of life were not analyzed, potentially leading to incongruence between radiographic outcomes and patient-centered outcomes. Furthermore, some definitions, such as PJK2SD, were historically applied to adolescent scoliosis, which presents distinct biomechanical and clinical characteristics compared to adult spinal deformity. These differences may limit the applicability of such definitions to the adult population examined in this study. Further studies should aim to validate these definitions prospectively in multi-institutional cohorts and consider broader clinical outcomes beyond reoperation to provide a more comprehensive understanding of PJK. Finally, it should be noted that no formal non-radiographic analysis was performed for definition PJK15 to definitively demonstrate its superiority in predicting clinical outcomes compared to other definitions (e.g. Delphi analysis). PJK15’s applicability was inferred from its statistical overlap with PJK30 – a definition with intrinsic clinical outcome considerations – and this concept should be evaluated more thoroughly in future studies.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the variability in PJK definitions and their implications for clinical and radiographic outcomes. Clinically relevant of symptomatic PJK often does not correspond to larger deviations in PJK angle, underscoring the importance of definitions that align with patient outcomes. Among the definitions evaluated, PJK30 demonstrated itself to be the most clinically relevant with strong alignment to reoperation rates, thus making it a robust option for identifying symptomatic PJK. PJK15, while similar to PJK30, relies purely on radiographic criteria and thus offers the advantage of enabling earlier diagnosis of PJK before clinical symptoms become apparent. In contrast, PJK20 and PJK10+10, though statistically viable, are limited by their reliance on UIV +2 measurements which are less practical than definitions that rely on UIV+1. These findings support the need for standardized PJK definitions that emphasize both clinical and radiographic relevance to improve consistency in research and surgical decision making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, TB, CM; methodology, TB; software, TB; validation, TB, KJ, CM; formal analysis, TB; investigation, TB, KJ, SV, MRC; resources, CM; data curation, TB, KJ, SV, MRC; writing—original draft preparation, TB, AY, KJ; writing—review and editing, TB, KJ, AY, MRC, CM; visualization, TB; supervision, CM; project administration, CM; funding acquisition, N/A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University in St. Louis (#202302010, 4-20-2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study were obtained from electronic medical records from Barnes-Jewish Hospital (St. Louis, MO) and contain protected health information. Due to institutional policies and patient confidentiality regulations, this data is not publicly available. Data access is restricted to approved researchers in compliance with ethical and regulatory requirements. Please contact Washington University’s Institutional Review Board for further information on data access.

Acknowledgments

Washington University School of Medicine’s Dean’s Medical Student Research Fellowship for the MPHS Yearlong Research Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. CAM is a consultant for Kuros, Augmedics, SMAIO, Baxter Health, and SI-Bone. The research conducted to acquire results of this study were not funded with any grants.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASD |

Adult Spinal Deformity |

| PJK |

Proximal Junctional Kyphosis |

| UIV |

Upper Instrumented Vertebra |

| SAV |

Supra-adjacent Vertebra |

| EMR |

Electronic Medical Record |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

References

- Kim HJ, Iyer S. Proximal Junctional Kyphosis. JAAOS - Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2016;24(5):318-326. [CrossRef]

- Diebo BG, Shah NV, Boachie-Adjei O, et al. Adult spinal deformity. Lancet. Jul 13 2019;394(10193):160-172. [CrossRef]

- Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Cho SK, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in primary adult deformity surgery: evaluation of 20 degrees as a critical angle. Neurosurgery. Jun 2013;72(6):899-906. [CrossRef]

- Sardar ZM, Kim Y, Lafage V, Rand F, Lenke L, Klineberg E. State of the art: proximal junctional kyphosis-diagnosis, management and prevention. Spine Deform. May 2021;9(3):635-644. [CrossRef]

- Glattes RC, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Kim YJ, Rinella A, Edwards C, 2nd. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity following long instrumented posterior spinal fusion: incidence, outcomes, and risk factor analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Jul 15 2005;30(14):1643-9. [CrossRef]

- Kim HJ, Lenke LG, Shaffrey CI, Van Alstyne EM, Skelly AC. Proximal junctional kyphosis as a distinct form of adjacent segment pathology after spinal deformity surgery: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Oct 15 2012;37(22 Suppl):S144-64. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Kim JU, Jang JS, Lee SH. Analysis of the incidence and risk factors for the progression of proximal junctional kyphosis following surgical treatment for lumbar degenerative kyphosis: minimum 2-year follow-up. Br J Neurosurg. Apr 2014;28(2):252-8. [CrossRef]

- Yagi M, King AB, Boachie-Adjei O. Incidence, risk factors, and natural course of proximal junctional kyphosis: surgical outcomes review of adult idiopathic scoliosis. Minimum 5 years of follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Aug 1 2012;37(17):1479-89. [CrossRef]

- Helgeson MD, Shah SA, Newton PO, et al. Evaluation of proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis following pedicle screw, hook, or hybrid instrumentation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Jan 15 2010;35(2):177-81. [CrossRef]

- Lonner BS, Newton P, Betz R, et al. Operative management of Scheuermann’s kyphosis in 78 patients: radiographic outcomes, complications, and technique. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Nov 15 2007;32(24):2644-52. [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh H, Gupta S, Jain A, El Dafrawy MH, Skolasky RL, Kebaish KM. Type of Anchor at the Proximal Fusion Level Has a Significant Effect on the Incidence of Proximal Junctional Kyphosis and Outcome in Adults After Long Posterior Spinal Fusion. Spine Deform. Jul 2013;1(4):299-305. [CrossRef]

- Kim HJ, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis results in inferior SRS pain subscores in adult deformity patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). May 15 2013;38(11):896-901. [CrossRef]

- Kim HJ, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Patients with proximal junctional kyphosis requiring revision surgery have higher postoperative lumbar lordosis and larger sagittal balance corrections. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Apr 20 2014;39(9):E576-80. [CrossRef]

- Boeckenfoerde K, Schulze Boevingloh A, Gosheger G, Bockholt S, Lampe LP, Lange T. Risk Factors of Proximal Junctional Kyphosis in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis-The Spinous Processes and Proximal Rod Contouring. J Clin Med. Oct 16 2022;11(20). [CrossRef]

- Hyun SJ, Lee BH, Park JH, Kim KJ, Jahng TA, Kim HJ. Proximal Junctional Kyphosis and Proximal Junctional Failure Following Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery. Korean J Spine. Dec 2017;14(4):126-132. [CrossRef]

- Hills J, Mundis GM, Klineberg EO, et al. The T4-L1-Hip Axis: Sagittal Spinal Realignment Targets in Long-Construct Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery: Early Impact. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Dec 4 2024;106(23):e48. [CrossRef]

- Petrosyan E, Fares J, Ahuja CS, et al. Genetics and pathogenesis of scoliosis. N Am Spine Soc J. Dec 2024;20:100556. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).