Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

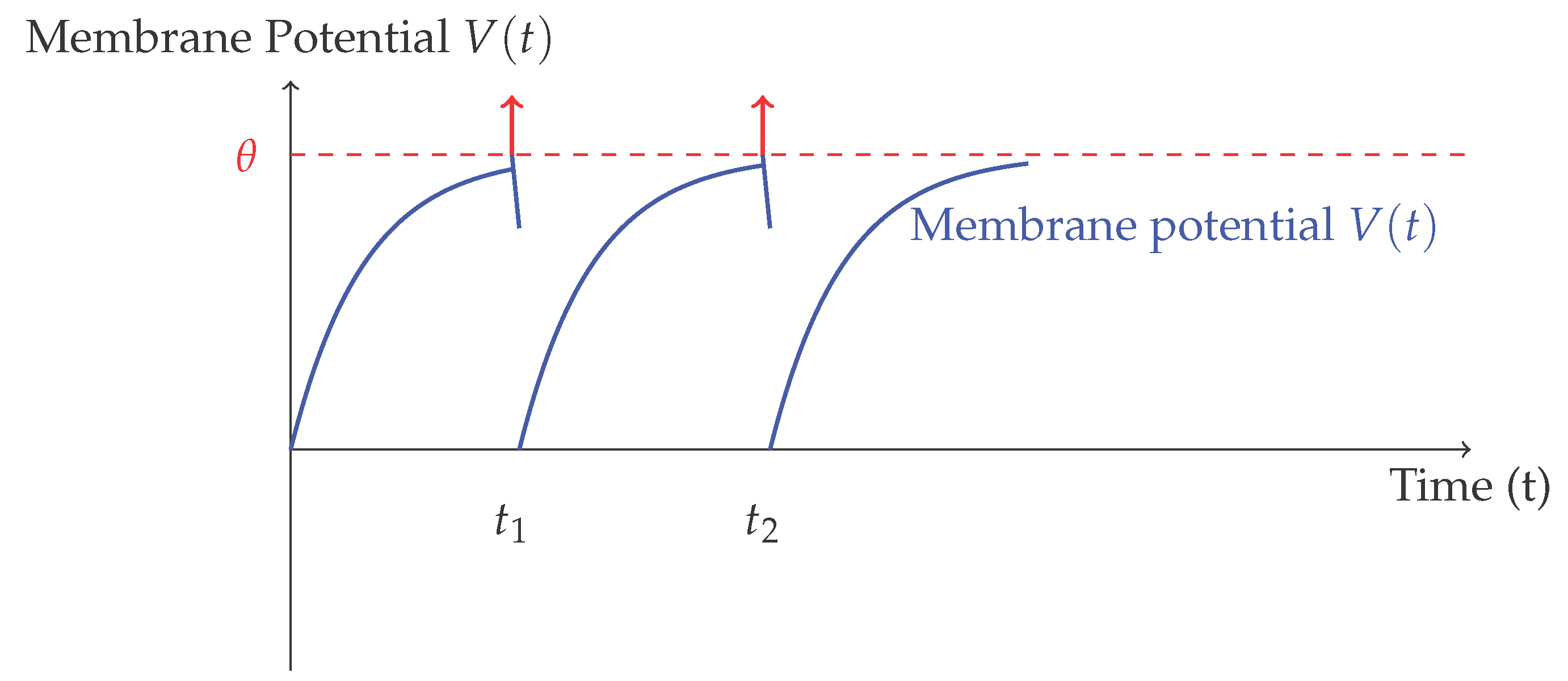

2. Spiking Neuron Models and Mathematical Formalism

3. Learning Algorithms for Large-Scale Spiking Neural Networks

4. Hardware and Software Infrastructures for Large-Scale SNNs

5. Benchmarking and Evaluation Metrics for Large-Scale SNNs

5.1. Benchmark Datasets

Static Image Datasets

Neuromorphic Datasets

Temporal Sequence Datasets

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

Accuracy and Latency

Energy Consumption

Sparsity and Spike Rate

Biological Plausibility and Interpretability

5.3. Challenges and Future Directions

6. Applications and Future Directions of Large-Scale Spiking Neural Networks

6.1. Robotics and Autonomous Systems

6.2. Sensory Processing and Brain-Machine Interfaces

6.3. Neuromorphic Computing and Edge AI

6.4. Future Research Directions

- Scalable and Efficient Learning: Developing biologically plausible, online learning algorithms that scale to millions of neurons while supporting complex cognitive tasks remains an open problem. Novel hybrid approaches combining local plasticity with global error signals are a promising avenue [116].

- Standardization and Benchmarking: The establishment of comprehensive benchmarks, standardized APIs, and interoperable toolchains will accelerate reproducibility and facilitate comparison across methods and platforms [117].

- Advanced Neuromorphic Hardware: Progress in analog and mixed-signal neuromorphic chips with enhanced plasticity mechanisms and scalable interconnects is vital for deploying large-scale SNNs in practical applications [120].

- Theoretical Foundations: A deeper theoretical understanding of information encoding, computational capacity, and generalization in SNNs will inform better architecture and algorithm design [121].

7. Conclusion

References

- Xing, X.; Gao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Clifton, D.A.; Xiao, S.; Du, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, J. SpikeLLM: Scaling up Spiking Neural Network to Large Language Models via Saliency-based Spiking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.04752, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, P.U.; Neil, D.; Binas, J.; Cook, M.; Liu, S.C.; Pfeiffer, M. Fast-classifying, high-accuracy spiking deep networks through weight and threshold balancing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, 2015, pp. 1–8.

- Xu, B.; Geng, H.; Yin, Y.; Li, P. DISTA: Denoising Spiking Transformer with intrinsic plasticity and spatiotemporal attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.09376, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rathi, N.; Roy, K. DIET-SNN: A low-latency spiking neural network with direct input encoding and leakage and threshold optimization. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 34, 3174–3182. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.S.; Rathi, N.; Roy, K. One timestep is all you need: Training spiking neural networks with ultra low latency. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.05929, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrogio, S.; Narayanan, P.; Tsai, H.; Shelby, R.M.; Boybat, I.; di Nolfo, C.; Sidler, S.; Giordano, M.; Bodini, M.; Farinha, N.C.; et al. Equivalent-accuracy accelerated neural-network training using analogue memory. Nature 2018, 558, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vedaldi, A.; Lenc, K. MatConvNet: Convolutional Neural Networks for Matlab. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2015, pp. 689–692.

- Fang, W.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Masquelier, T.; Huang, T.; Tian, Y. Incorporating learnable membrane time constant to enhance learning of spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 2661–2671.

- Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Li, G.; Zhu, J.; Xie, Y.; Shi, L. Direct training for spiking neural networks: Faster, larger, better. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 1311–1318.

- Zhang, W.; Li, P. Temporal spike sequence learning via backpropagation for deep spiking neural networks. Proceeddings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing 2020, 33, 12022–12033. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Ji, R.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huang, F.; Lin, C.W. Rotated binary neural network. Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 7474–7485. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, C.; Yu, L.; Huang, L.; Ma, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhou, H.; Tian, Y. SGLFormer: Spiking Global-Local-Fusion Transformer with high performance. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2024, 18, 1371290. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, T.; Xu, B. Attention-free Spikformer: Mixing Spike Sequences with Simple Linear Transforms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.02557, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Q.; Hesham, M.; Fabio, S.; Dora, S. A reconfigurable on-line learning spiking neuromorphic processor comprising 256 neurons and 128K synapses. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2015, 9, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Li, Y.; Park, H.; Venkatesha, Y.; Panda, P. Neural architecture search for spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2022, pp. 36–56.

- Wang, P.; He, X.; Li, G.; Zhao, T.; Cheng, J. Sparsity-inducing binarized neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 12192–12199.

- Google. Cloud TPU.

- Zhang, J.; Dong, B.; Zhang, H.; Ding, J.; Heide, F.; Yin, B.; Yang, X. Spiking transformers for event-based single object tracking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 8801–8810.

- Yu, W.; Si, C.; Zhou, P.; Luo, M.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, J.; Yan, S.; Wang, X. Metaformer baselines for vision. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023, 46, 896–912. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Jin, X.; Sun, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Hu, Y.; Yang, F.; Tang, H.; Zhu, X.; Lin, P.; et al. Darwin3: a large-scale neuromorphic chip with a novel ISA and on-chip learning. National Science Review 2024, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Xu, C.; Han, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Tan, K.C. Progressive tandem learning for pattern recognition with deep spiking neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, 44, 7824–7840. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, H.; Fan, X.; Tian, Y. Enhancing the Performance of Transformer-based Spiking Neural Networks by Improved Downsampling with Precise Gradient Backpropagation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.05954, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. The Journal of Physiology 1952, 117, 500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- APT Advanced Processor Technologies Research Group. SpiNNaker.

- Yang, S.; Ma, H.; Yu, C.; Wang, A.; Li, E.P. SDiT: Spiking Diffusion Model with Transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.11588, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, A.A.; Lin, L.; Nguyen, H.; Rao, V.; Sharma, T.; Wijayawardana, R. Reducing the Carbon Impact of Generative AI Inference (today and in 2035). In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Sustainable Computer Systems, 2023, pp. 1–7.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30, 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Che, K.; Fang, W.; Tian, K.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, S.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, L. Spikformer V2: Join the High Accuracy Club on ImageNet with an SNN Ticket. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.02020, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Tang, H.; Pan, G. Spiking Deep Residual Networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 34, 5200–5205. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesha, Y.; Kim, Y.; Tassiulas, L.; Panda, P. Federated learning with spiking neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2021, 69, 6183–6194. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, A. The growing energy footprint of artificial intelligence. Joule 2023, 7, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, M.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Deng, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, G. Attention spiking neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023, 45, 9393–9410. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Xiao, M.; Yan, S.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Luo, Z.Q. Training High-Performance Low-Latency Spiking Neural Networks by Differentiation on Spike Representation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 12444–12453.

- Sun, Y.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Cao, N.; O’Hared, G. SpikeGraphormer: A High-Performance Graph Transformer with Spiking Graph Attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.15480, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Hu, K.; Zhang, T.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Chen, F. Spatio-Temporal Approximation: A Training-Free SNN Conversion for Transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Ma, Z. IM-loss: information maximization loss for spiking neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 156–166. [Google Scholar]

- Arafa, Y.; ElWazir, A.; ElKanishy, A.; Aly, Y.; Elsayed, A.; Badawy, A.H.; Chennupati, G.; Eidenbenz, S.; Santhi, N. Verified instruction-level energy consumption measurement for NVIDIA GPUs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Computing Frontiers, 2020, pp. 60–70.

- Zhang, J.; Shen, J.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Yan, R.; Pan, G.; Tang, H. SpikingMiniLM: Energy-efficient Spiking Transformer for Natural Language Understanding. Science China Information Sciences 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, S.B.; Orchard, G. SLAYER: Spike layer error reassignment in time. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018, pp. 1412–1421.

- Qin, H.; Gong, R.; Liu, X.; Shen, M.; Wei, Z.; Yu, F.; Song, J. Forward and backward information retention for accurate binary neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020, pp. 2250–2259.

- Izhikevich, E.M. Which model to use for cortical spiking neurons? IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 2004, 15, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Identity mappings in deep residual networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2016, pp. 630–645.

- Deng, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gu, S. Temporal Efficient Training of Spiking Neural Network via Gradient Re-weighting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Jiang, X.; Pan, G. Fast-SNN: Fast Spiking Neural Network by Converting Quantized ANN. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023, 45, 14546–14562. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Fan, X.; Deng, X.; Hong, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, Z. TE-Spikformer: Temporal-enhanced spiking neural network with transformer. Neurocomputing, 2024; 128268. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Tang, J.; Li, H.; Qi, J.; Li, S.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H. Spiking-PhysFormer: Camera-Based Remote Photoplethysmography with Parallel Spike-driven Transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.04798, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mahowald, M.A. Silicon retina with adaptive photoreceptors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SPIE/SPSE Symposium on Electronic Science and Technology: from Neurons to Chips, 1991, Vol. 1473, pp. 52–58.

- Shen, S.; Zhao, D.; Shen, G.; Zeng, Y. TIM: An Efficient Temporal Interaction Module for Spiking Transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.11687, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wong, W.F. Near Lossless Transfer Learning for Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 10577–10584.

- Yan, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Feng, L.; Ma, D.; Li, H.; Pan, G. Efficient spiking neural network design via neural architecture search. Neural Networks, 2024; 106172. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, B.; Luo, W.; Yang, X.; Liu, W.; Cheng, K.T. Bi-real net: Enhancing the performance of 1-bit cnns with improved representational capability and advanced training algorithm. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2018, pp. 722–737.

- Zhu, R.J.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, T.; Deng, H.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Deng, L.J. TCJA-SNN: Temporal-channel joint attention for spiking neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.10177, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.; Ahn, J.; Yoo, S. Weighted-entropy-based quantization for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2017, pp. 5456–5464.

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yan, R.; Tang, H. Deep spiking neural networks with binary weights for object recognition. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liang, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, T. RTFormer: Re-parameter TSBN Spiking Transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.14180, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Cao, J.; Chen, H.; Xu, R. Spiking Wavelet Transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.11138, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Panda, P. Optimizing deeper spiking neural networks for dynamic vision sensing. Neural Networks 2021, 144, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Deng, S.; Dong, X.; Gu, S. Error-Aware Conversion from ANN to SNN via Post-training Parameter Calibration. International Journal of Computer Vision 2024, pp. 1–24.

- Gerstner, W.; Kistler, W.M. Spiking neuron models: Single neurons, populations, plasticity; Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Bohte, S.M.; Kok, J.N.; La Poutré, J.A. SpikeProp: backpropagation for networks of spiking neurons. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Symposium on Artificial Neural Networks, 2000, Vol. 48, pp. 419–424.

- Lian, S.; Shen, J.; Wang, Z.; Tang, H. IM-LIF: Improved Neuronal Dynamics With Attention Mechanism for Direct Training Deep Spiking Neural Network. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C.J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; Van Den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Esser, S.K.; Merollaa, P.A.; Arthura, J.V.; Cassidya, A.S.; Appuswamya, R.; Andreopoulosa, A.; Berga, D.J.; McKinstrya, J.L.; Melanoa, T.; Barcha, D.R.; et al. Convolutional networks for fast energy-efficient neuromorphic computing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 11441–11446. [Google Scholar]

- Borst, A.; Theunissen, F.E. Information theory and neural coding. Nature Neuroscience 1999, 2, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Na, B.; Mok, J.; Park, S.; Lee, D.; Choe, H.; Yoon, S. AutoSNN: Towards energy-efficient spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2022, pp. 16253–16269.

- Benjamin, B.V.; Gao, P.; McQuinn, E.; Choudhary, S.; Chandrasekaran, A.R.; Bussat, J.M.; Alvarez-Icaza, R.; Arthur, J.V.; Merolla, P.A.; Boahen, K. Neurogrid: A mixed-analog-digital multichip system for large-scale neural simulations. Proceedings of the IEEE 2014, 102, 699–716. [Google Scholar]

- Masquelier, T.; Thorpe, S.J. Unsupervised learning of visual features through spike timing dependent plasticity. PLoS Computational Biology 2007, 3, e31. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Chen, P.; Zhuang, f.B.; Shen, C.; Zhang, B.; Ding, W. SA-BNN: State-aware binary neural network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 2091–2099.

- Glorot, X.; Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings, 2010, pp. 249–256.

- Deng, S.; Gu, S. Optimal conversion of conventional artificial neural networks to spiking neural networks. Proceedigns of the International Conference on Learning Representations 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, J.D.; Carvalho, M.; Carneiro, D.; Cardoso, J.S. Spiking neural networks: A survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 60738–60764. [Google Scholar]

- Maass, W. Lower bounds for the computational power of networks of spiking neurons. Neural Computation 1996, 8, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, A.; Beerel, P.A. Spiking Neural Networks with Dynamic Time Steps for Vision Transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.16456, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Gotarredona, T.; Linares-Barranco, B. A 128×128 1.5% Contrast Sensitivity 0.9% FPN 3 μs Latency 4 mW Asynchronous Frame-Free Dynamic Vision Sensor Using Transimpedance Preamplifiers. IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits 2013, 48, 827–838. [Google Scholar]

- Nvidia. Nvidia V100 Tensor Core GPU.

- Dampfhoffer, M.; Mesquida, T.; Valentian, A.; Anghel, L. Backpropagation-based learning techniques for deep spiking neural networks: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Huang, T.; Masquelier, T.; Tian, Y. Deep residual learning in spiking neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 21056–21069. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Furber, S. Noisy softplus: A biology inspired activation function. In Proceedings of the Proceeddings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing. Springer; 2016; pp. 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Srinivasan, G.; Roy, K. RMP-SNN: Residual membrane potential neuron for enabling deeper high-accuracy and low-latency spiking neural network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020, pp. 13558–13567.

- Thorpe, S.; Delorme, A.; Van Rullen, R. Spike-based strategies for rapid processing. Neural Networks 2001, 14, 715–725. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rullen, R.; Thorpe, S.J. Rate coding versus temporal order coding: what the retinal ganglion cells tell the visual cortex. Neural Computation 2001, 13, 1255–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Simard, P.; Frasconi, P. Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 1994, 5, 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Delbruck, T.; Pfeiffer, M. Training deep spiking neural networks using backpropagation. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2016, 10, 508. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, P.; Neil, D.; Liu, S.C.; Delbruck, T.; Pfeiffer, M. Real-time classification and sensor fusion with a spiking deep belief network. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2013, 7, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Rathi, N.; Chakraborty, I.; Kosta, A.; Sengupta, A.; Ankit, A.; Panda, P.; Roy, K. Exploring neuromorphic computing based on spiking neural networks: Algorithms to hardware. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ponulak, F.; Kasiński, A. Supervised learning in spiking neural networks with ReSuMe: sequence learning, classification, and spike shifting. Neural Computation 2010, 22, 467–510. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Tong, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Huang, X. RecDis-SNN: Rectifying membrane potential distribution for directly training spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 326–335.

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Memory-Efficient Reversible Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 16759–16767.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lew, L. PokeBNN: A Binary Pursuit of Lightweight Accuracy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 12475–12485.

- Bi, G.q.; Poo, M.m. Synaptic modifications in cultured hippocampal neurons: dependence on spike timing, synaptic strength, and postsynaptic cell type. Journal of Neuroscience 1998, 18, 10464–10472. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, L.; Huang, L.; Fan, X.; Yuan, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, H.; Tian, Y. QKFormer: Hierarchical Spiking Transformer using QK Attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.16552, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin, W.H.; Stevens, C.F. Synaptic noise and other sources of randomness in motoneuron interspike intervals. Journal of Neurophysiology 1968, 31, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eshraghian, J.K.; Ward, M.; Neftci, E.; Wang, X.; Lenz, G.; Dwivedi, G.; Bennamoun, M.; Jeong, D.S.; Lu, W.D. Training spiking neural networks using lessons from deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.12894, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhoty, B.; Bojkovic, V.; de Vazelhes, W.; Zhao, X.; De Masi, G.; Xiong, H.; Gu, B. Direct training of snn using local zeroth order method. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36, 18994–19014. [Google Scholar]

- VanRullen, R.; Thorpe, S.J. Surfing a spike wave down the ventral stream. Vision Research 2002, 42, 2593–2615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.J.; Zhao, Q.; Eshraghian, J.K. SpikeGPT: Generative pre-trained language model with spiking neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13939, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Yao, X.; Li, F.; Mo, Z.; Cheng, J. GLIF: A unified gated leaky integrate-and-fire neuron for spiking neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 32160–32171. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Tian, L.; Shan, Y. Improving Low-Precision Network Quantization via Bin Regularization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp. 5261–5270.

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Venkatesha, Y.; Moitra, A.; Panda, P. MIME: Adapting a Single Neural Network for Multi-task Inference with Memory-efficient Dynamic Pruning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.05274, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G.E. Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, T.; Ding, J.; Yu, Z.; Huang, T. Optimized potential initialization for low-latency spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, Vol. 36, pp. 11–20.

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Peng, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Ma, Z. Membrane potential batch normalization for spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 19420–19430.

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, Y.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Yan, S.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, L. Spikformer: When spiking neural network meets transformer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; He, X.; Sun, J.; Vasconcelos, N. Deep learning with low precision by half-wave gaussian quantization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2017, pp. 5918–5926.

- Wang, Z.; Fang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Xu, R. Masked spiking transformer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 1761–1771.

- Merolla, P.A.; Arthur, J.V.; Alvarez-Icaza, R.; Cassidy, A.S.; Sawada, J.; Akopyan, F.; Jackson, B.L.; Imam, N.; Guo, C.; Nakamura, Y.; et al. A million spiking-neuron integrated circuit with a scalable communication network and interface. Science 2014, 345, 668–673. [Google Scholar]

- Collobert, R.; Weston, J.; Bottou, L.; Karlen, M.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kuksa, P. Natural language processing (almost) from scratch. Journal of Machine Learning Sesearch 2011, 12, 2493–2537. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.C.; van Schaik, A.; Mincti, B.A.; Delbruck, T. Event-based 64-channel binaural silicon cochlea with Q enhancement mechanisms. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems. IEEE, 2010, pp. 2027–2030.

- Lichtsteiner, P.; Posch, C.; Delbruck, T. A 128 × 128 120db 30mw asynchronous vision sensor that responds to relative intensity change. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference. IEEE; 2006; pp. 2060–2069. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Deng, S.; Hai, Y.; Gu, S. Differentiable spike: Rethinking gradient-descent for training spiking neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 23426–23439. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Shi, X.; Hao, Z.; Bu, T.; Ding, J.; Yu, Z.; Huang, T. Towards High-performance Spiking Transformers from ANN to SNN Conversion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM Multimedia; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Venkatesha, Y.; Panda, P. Privatesnn: Fully privacy-preserving spiking neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.03414, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman, C.D.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Parsa, M.; Mitchell, J.P.; Date, P.; Kay, B. Opportunities for neuromorphic computing algorithms and applications. Nature Computational Science 2022, 2, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adrian, E.D.; Zotterman, Y. The impulses produced by sensory nerve endings: Part 3. Impulses set up by Touch and Pressure. The Journal of Physiology 1926, 61, 465. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Gu, Z.; Li, D.; Wang, G.; Wang, A.; Li, E. STSC-SNN: Spatio-Temporal Synaptic Connection with temporal convolution and attention for spiking neural networks. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2022, 16, 1079357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Wang, W. Additive powers-of-two quantization: An efficient non-uniform discretization for neural networks. Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zenke, F.; Neftci, E.O. Brain-inspired learning on neuromorphic substrates. Proceedings of the IEEE 2021, 109, 935–950. [Google Scholar]

| Algorithm | Biological Plausibility | Scalability | Hardware Efficiency | Task Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Gradient Descent | Low | High (with BPTT) | Medium | High (competitive with ANNs) |

| Spike-Timing Dependent Plasticity (STDP) | High | Medium | High | Low to Medium |

| ANN-to-SNN Conversion | Low | High | Medium to Low | High (rate-coded) |

| Event-driven Contrastive Hebbian Learning | Medium | Medium | High | Medium |

| Reinforcement Learning (e.g., reward-modulated STDP) | Medium | Low | High | Medium (task-specific) |

| E-prop (eligibility propagation) | Medium to High | High (local learning) | High | Medium to High |

| Platform | Architecture | Neuron Count | Energy Efficiency | Programmability / Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intel Loihi | Digital neuromorphic | neurons per chip | pJ/spike | On-chip learning, programmable microcode |

| IBM TrueNorth | Digital neuromorphic | million neurons per chip | pJ/spike | Fixed synapse programming, no on-chip learning |

| BrainScaleS | Analog neuromorphic | neurons | Sub-nJ/spike | Plasticity via off-chip learning algorithms |

| NEST Simulator | Software (CPU/GPU) | Millions of neurons (distributed) | Depends on hardware | Highly flexible, BPTT support with surrogate gradients |

| Brian2 Simulator | Software (CPU/GPU) | Up to hundreds of thousands | Depends on hardware | User-defined models and custom learning rules |

| BindsNET | Software (GPU) | Tens of thousands | Moderate | Focused on reinforcement learning and spike-based algorithms |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).