1. Introduction: The Canonical Fractal

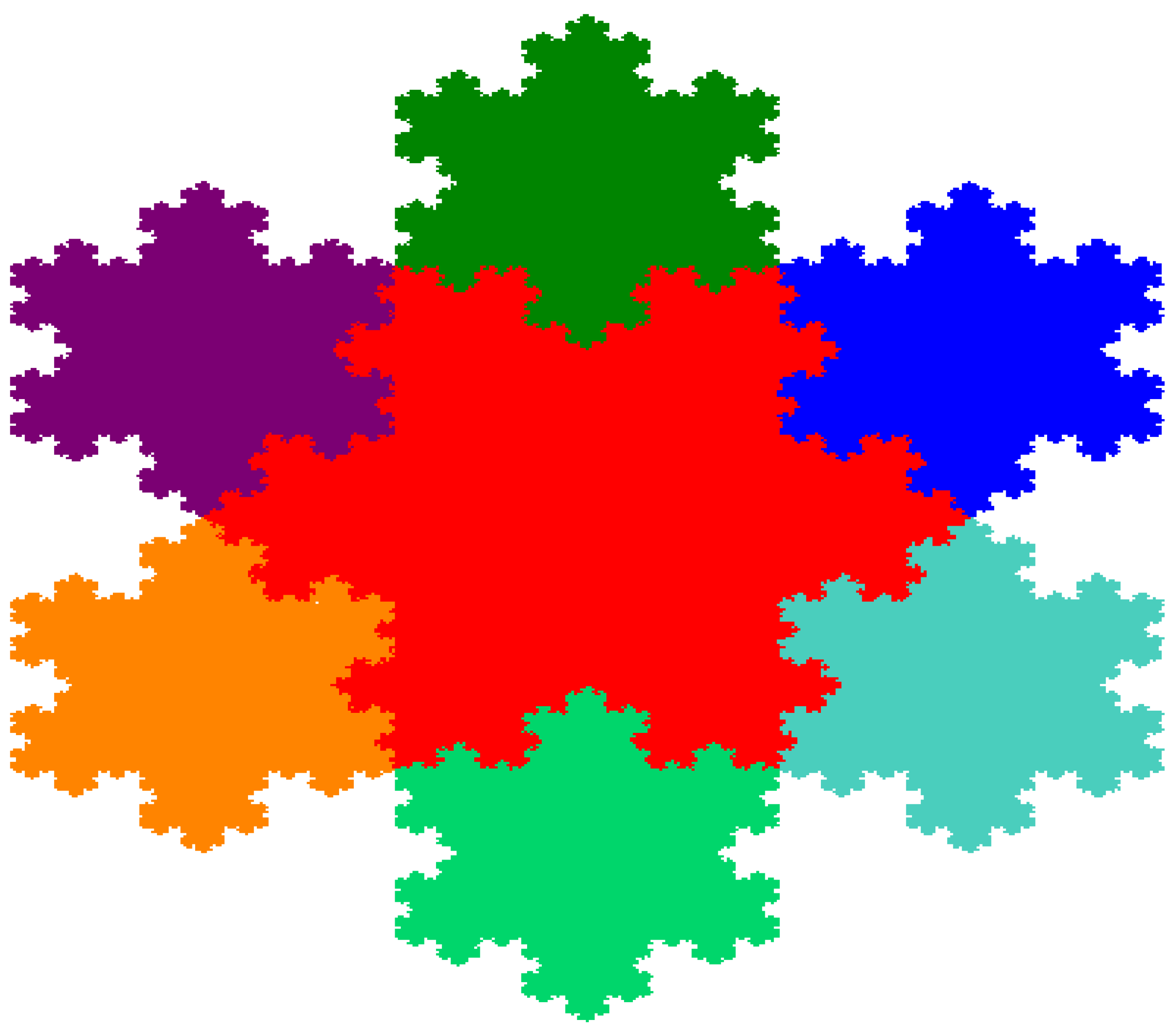

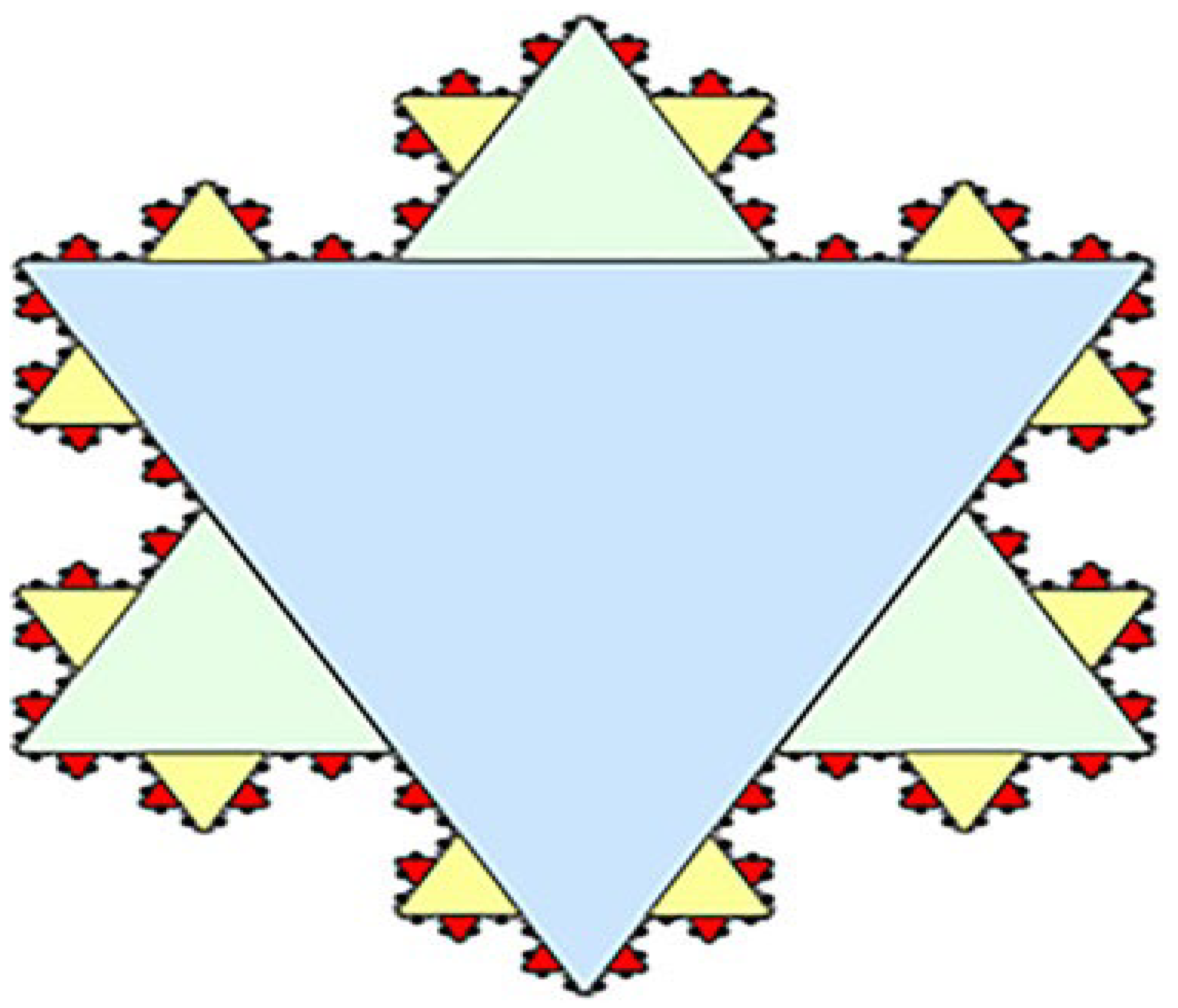

In the late twentieth century, Benoit Mandelbrot (Mageed and Bhat, 2022; Mageed, 2023; Mageed, 2024 a-m, Mageed and Li, 2025; Mageed, 2025 a-c) revolutionised the intriguing world of fractals, which are objects that exhibit self-similarity across different scales. One of the most stunning examples in this category is the Koch snowflake, as depicted in

Figure 1 (Husain et al., 2021) and

Figure 2 (c.f., Peitgen et al., 2004), a wonderful work of grace and clarity. The amazing geometry of Koch snowflake is manifested through

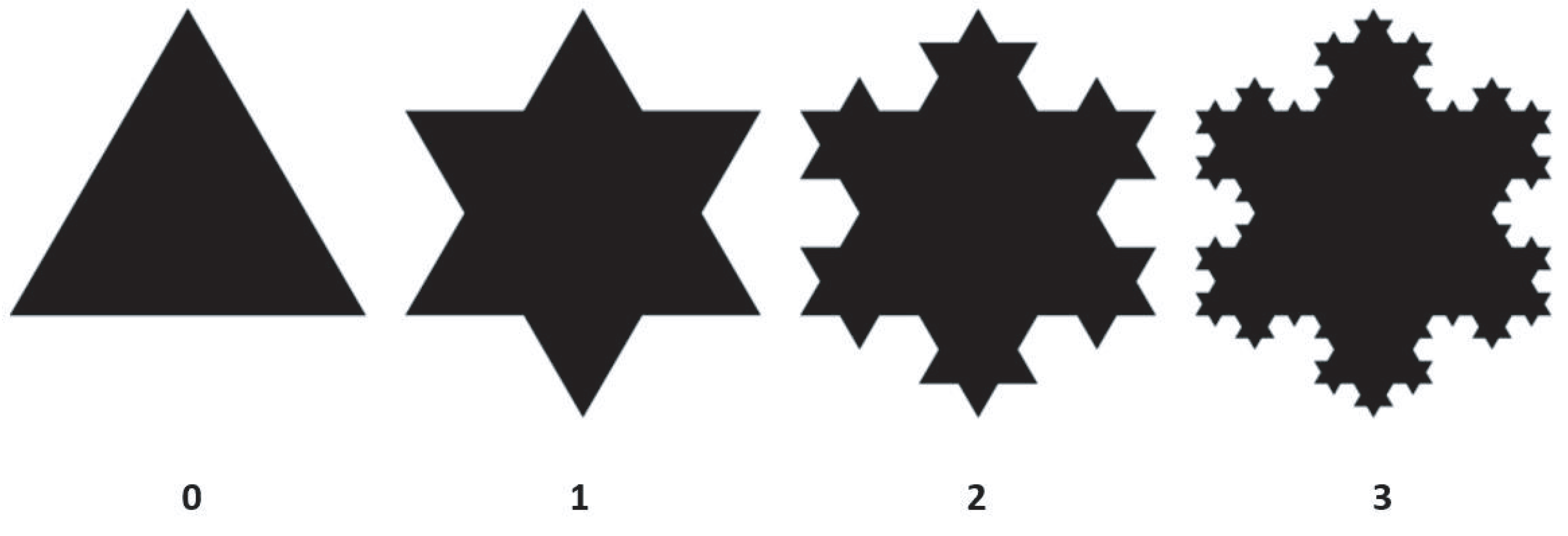

It all begins with an equilateral triangle known as the initiator. In each stage of the process, or iteration, the middle third of each line segment is changed by two sides of a smaller equilateral triangle pointing outward—this is known as the generator.

And this process goes on forever (von Koch, 1904; Aravindraj et al., 2023). The visual illustration is showcased by

Figure 3 (c.f., Aravindraj et al., 2023).

What’s truly remarkable about the Koch snowflake is that it has two well-known properties. First, its perimeter is infinite. The boundary length rises by a factor of with each iteration, resulting in an ever-expanding perimeter as the iterations continue indefinitely. Second, despite its infinite perimeter, the area is finite, eventually reducing to (8/5) the area of the original triangle (Akhmet et al., 2020). This intriguing mix of finite and infinite measurements within a single geometric shape is a fundamental aspect of fractal geometry. Additionally, the Koch curve is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere, which posed a significant challenge to traditional calculus (Husain et al., 2022a, 2022b). It has a Hausdorff dimension of , which indicates its “roughness” or ability to fill space. This means that is more than simply a one-dimensional line but not nearly a two-dimensional plane (Bunimovich and Skums (2024). While these qualities are well understood, they pave the way for even more profound, unresolved concerns.

2. Open Problem 1: The Physical Realisation and Quantum Limit

There’s a fascinating open question about how the Koch snowflake appears in the physical world. While the math behind it suggests infinite iterations, creating detail at incredibly tiny scales, the reality is that our universe isn’t just a mathematical abstraction. The Planck length, which is about 1.6 x

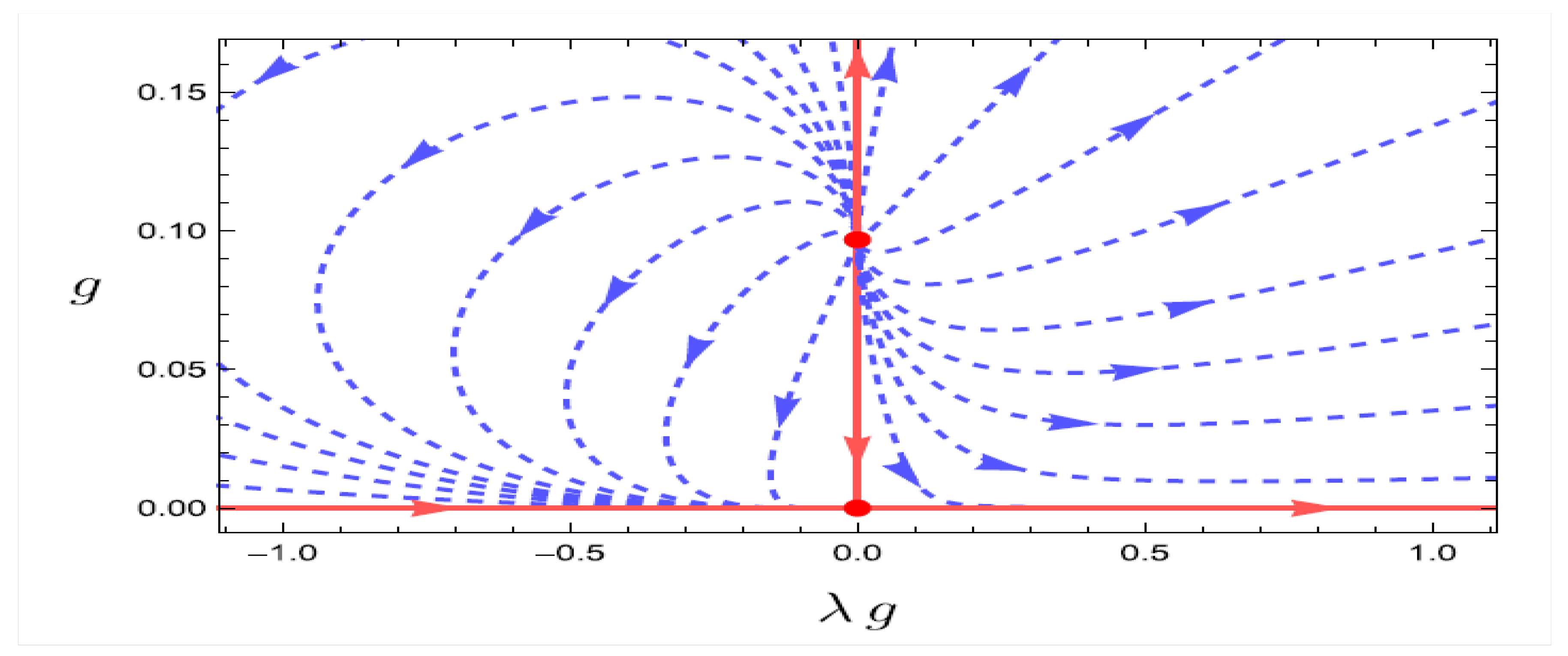

meters, is thought to be the smallest meaningful distance, marking a fundamental limit to how we understand space (Cahn and Quigg, 2023). This sets a hard boundary on any physical fractal creation. This brings us to an important question: how do the characteristics of a “real-world Koch snowflake” differ from the ideal model as we get closer to the Planck scale? Research in quantum gravity and string theory hints that spacetime might have a fractal nature at this scale (Kluth, 2025). In

Figure 4 (Kluth, 2025), the authors present a phase diagram that illustrates the behavior of the β-functions, which describe how certain parameters change in a quantum gravity theory when the energy scale varies. The diagram focuses on the region where the Newton coupling (g) is positive. The nontrivial fixed point, labelled FPUV, indicates a stable condition where nearby trajectories in the diagram will eventually converge, suggesting that the system behaves consistently as energy increases (in the ultraviolet or UV region). This diagram helps scientists visualize the behavior of these parameters and identify important points, such as fixed points, where the system’s properties remain unchanged under certain conditions. Understanding this phase diagram is crucial for studying the stability and behavior of quantum gravity theories.

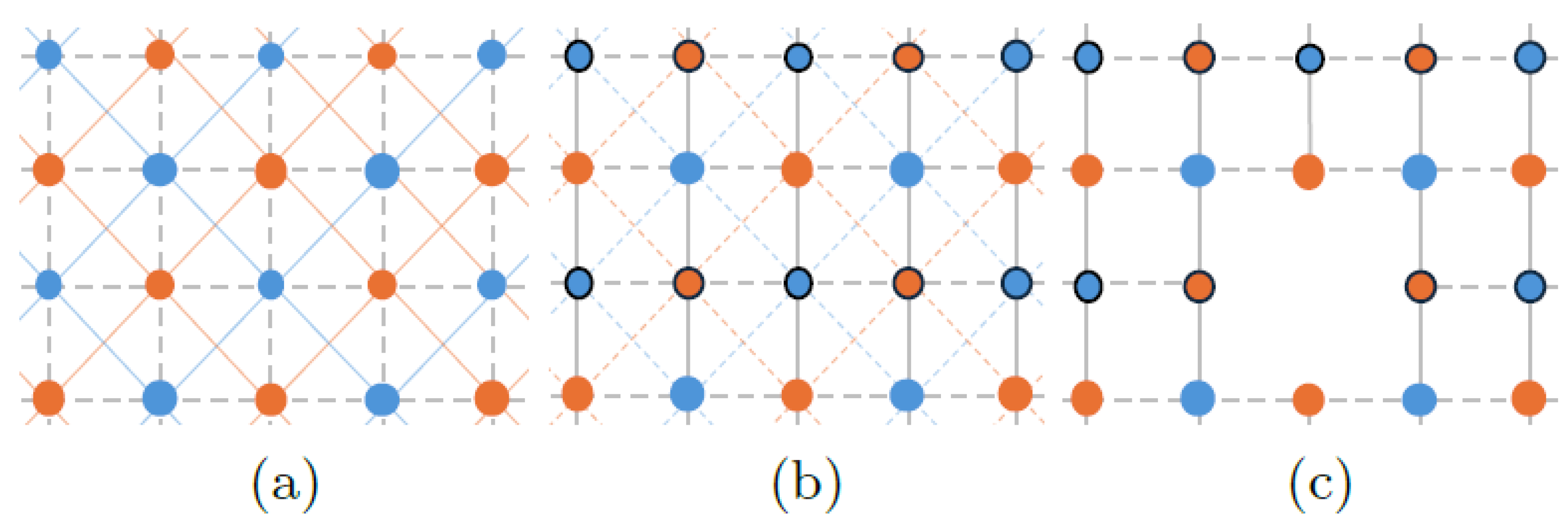

A physical version of the Koch structure, like a self-assembling polymer or a quantum dot array, would face limitations not just from the Planck scale but also from the specific laws of quantum mechanics and the inter-atomic forces that govern its components (Yuan and Crawford, 2024). “Order by Disorder” refers to a phenomenon in certain models of magnetism, specifically in an XY model on a two-dimensional lattice. In this context (Yuan and Crawford, 2024), the model has two types of interactions: nearest neighbour (NN) couplings that are ferromagnetic (favouring alignment) and next-nearest neighbour (NNN) couplings that are antiferromagnetic (favoring opposite alignment). The process involves manipulating the lattice structure(Yuan and Crawford, 2024), such as changing the interactions through a gauge transformation, which can lead to a stable arrangement of spins even when some interactions are removed, creating an imbalance that influences the overall magnetic order. This is depicted in

Figure 5 (c.f., Henley, 1989)

The exciting part is using truncated Koch models to explore how physical laws change with scale. For example, how does the electromagnetic resonance of a Koch fractal antenna shift when its smallest parts get close to a size where quantum tunnelling starts to play a role? (Karmakar, 2021). Additionally, could the energy states of a quantum system trap in a Koch-shaped potential well shed light on the relationship between geometric constraints and quantum behavior? (Mohammad et al., 2025). To tackle these questions, we need a fresh theoretical approach that combines the idealized world of fractal geometry with the discrete and probabilistic aspects of quantum mechanics (Golmankhaneh and Bongiorno, 2024).

3. Open Problem 2: The Optimal Packing Problem

In the realm of classical geometry, packing problems—like figuring out how to arrange circles or squares to cover a plane as densely as possible—are famously tricky. The Koch snowflake adds another layer of complexity with its detailed, non-convex edges. It’s been established that you can’t tile the plane perfectly with just one size of Koch snowflakes without leaving some gaps. This leads us to a fascinating question: what’s the densest way to pack identical Koch snowflakes in the Euclidean plane? This puzzle is still open-ended. Unlike convex polygons, which have clearer packing densities (Hales, 2024), the fractal nature of the snowflake presents a maze of interlocking shapes that are tough to navigate computationally. The intricate “fjords” and “peninsulas” hint that the best arrangement could be incredibly complex and non-repetitive (Brown, 2024). There’s also a related, even trickier challenge involving Apollonian-style packing: how can we achieve the densest arrangement using different sizes of Koch snowflakes? These packings would also be fractal and could have significant implications for materials science, especially in creating composites with the highest interfacial surface area for a given volume(Mageed and Bhat, 2022; Mageed, 2023; Mageed, 2024 a-m, Mageed and Li, 2025; Mageed, 2025 a-c). Looking ahead, research in this field will probably depend on advanced computational algorithms and machine learning techniques. By training models on extensive datasets of packing simulations, we might uncover innovative, high-density configurations that go beyond human intuition and traditional optimization methods(Jeanjean and Lu, 2022). Finding a solution would be a breakthrough in discrete geometry and could lead to new materials designed for optimal thermal or acoustic properties.

4. Open Problem 3: Higher-Dimensional Analogues

Exploring the Koch snowflake in three or more dimensions is quite a challenge and opens a captivating array of unsolved problems. While we can easily visualize a 2D snowflake made up of lines, imagining a 3D version could mean creating a surface or even a volume. One interesting method involves crafting a “Koch surface” by starting with a tetrahedron and then adding smaller tetrahedra to the center of each triangular face in a repetitive manner. This technique results in an object that has a finite volume but an infinite surface area (Fischer, 2020). However, the characteristics of this “Koch tetrahedron” or the “Sierpinski-Koch” hybrid remain somewhat mysterious. Questions like its Hausdorff dimension and its topological features, such as its genus as the iterations progress, are still up for debate (Kupczynski, 2024). Another intriguing option is to create a 3D volume-filling version of the Koch curve, which is a one-dimensional curve that touches every point within a 3D cube, much like the Hilbert curve. The construction and properties of such a curve, which would be a more intricate generalization of the Koch generator, are currently being explored in theoretical research (Aguiar e Oliveira Jr , 2022). These higher-dimensional inquiries aren’t just for academic curiosity. For applications that require high surface-to-volume ratios, the concept of having an infinite surface area within a finite volume is very pertinent. A 3D Koch-like structure, for example, might serve as a heat exchanger, a highly efficient catalyst bed, or even a model for the porous materials found in nature, such as sponges or lungs (West, 2024). To take advantage of these N-dimensional Koch analogues in practice, a strong mathematical foundation must be established. The Three-Body Problem (TBP) involves understanding how three objects, or point masses, move under the influence of their mutual gravitational attraction. This system is described by nine complex equations, and there isn’t a general solution for all scenarios, as their motion tends to be chaotic, see

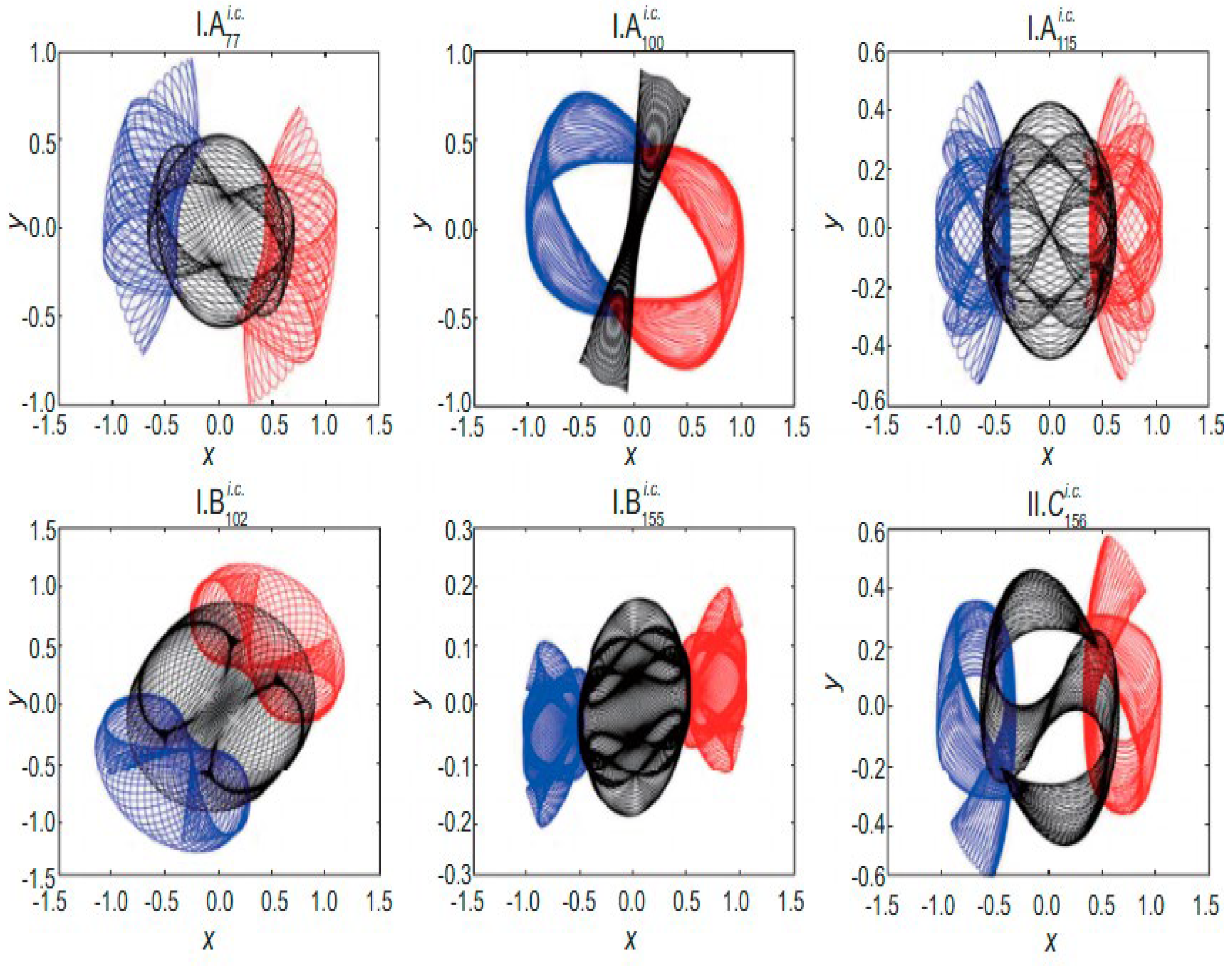

Figure 6 (c.f., Kupczynski, 2024).

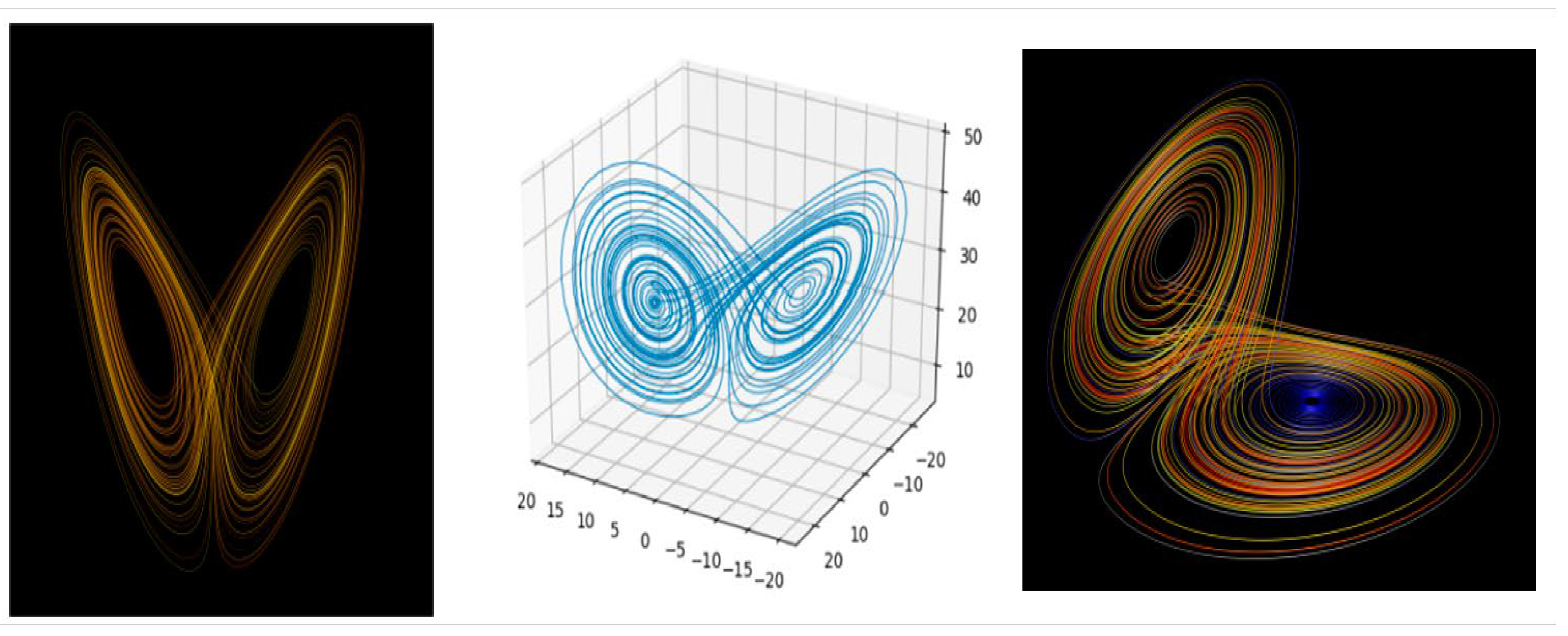

The Lorenz attractor is a well-known example in chaos theory(Kupczynski, 2024), illustrating how small changes in initial conditions can lead to vastly different outcomes, famously referred to as the “butterfly effect.” Edward Lorenz developed this concept using three simple equations to model how air moves in the atmosphere(Kupczynski, 2024), discovering that while the system is deterministic (meaning it follows specific rules), it is impossible to make accurate long-term predictions about its behavior. Despite this unpredictability(Kupczynski, 2024), Lorenz found that the system’s behavior is confined to a certain area in space, which is represented by the Lorenz attractor, see

Figure 7 (Kupczynski, 2024).

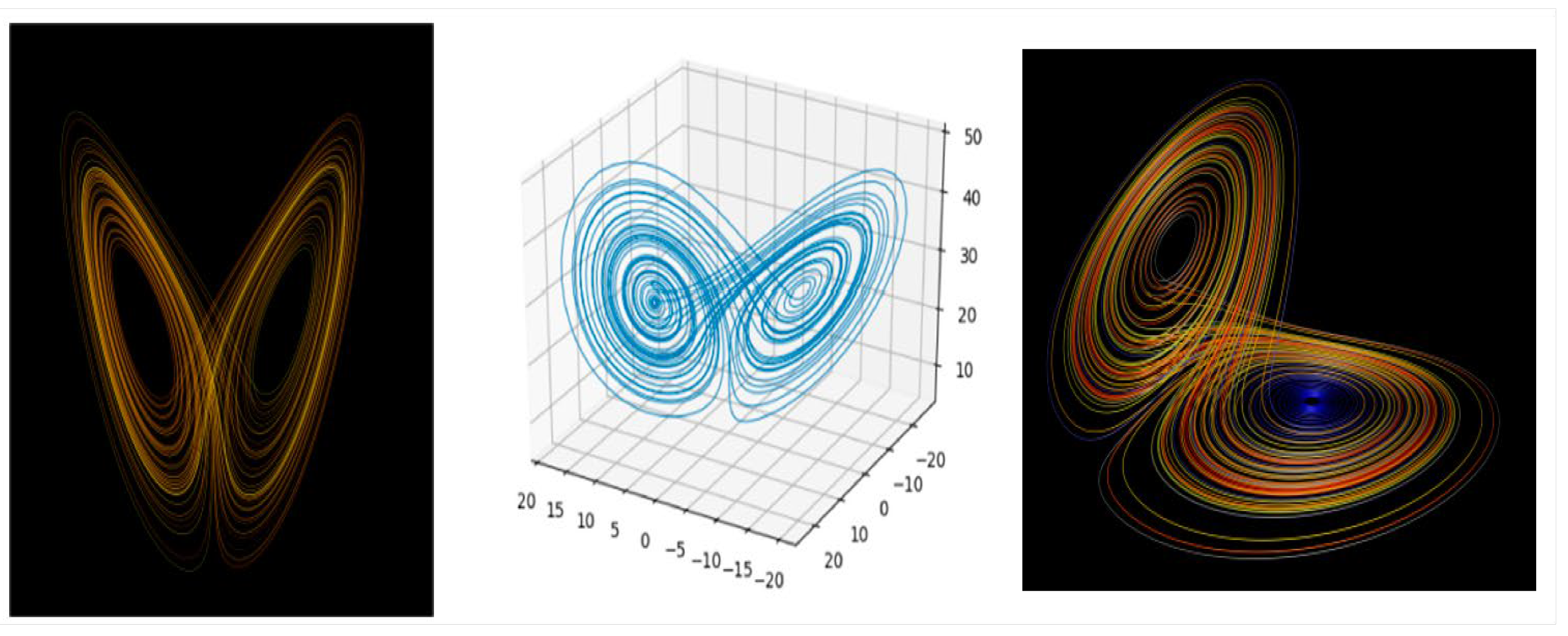

The fractality of nature is exposed by

Figure 8 (Kupczynski, 2024).

Outlook

The Koch snowflake is a vibrant centre of research rather than merely a completed mathematical topic. Its future is directly tied to advancements in three key areas:

Computation: We can anticipate extremely detailed simulations of Koch-like systems as parallel computer capacity, like as GPUs, continues to grow.

This will help us dive into packing problems and physical models at nearly atomic scales (Dally et al., 2021).

Materials Science: Thanks to advancements in nanofabrication and self-assembly, we might soon be able to create real-life Koch structures. This opens a hands-on way to test theoretical predictions about how they behave in quantum and electromagnetic contexts (Kabashin et al., 2023).

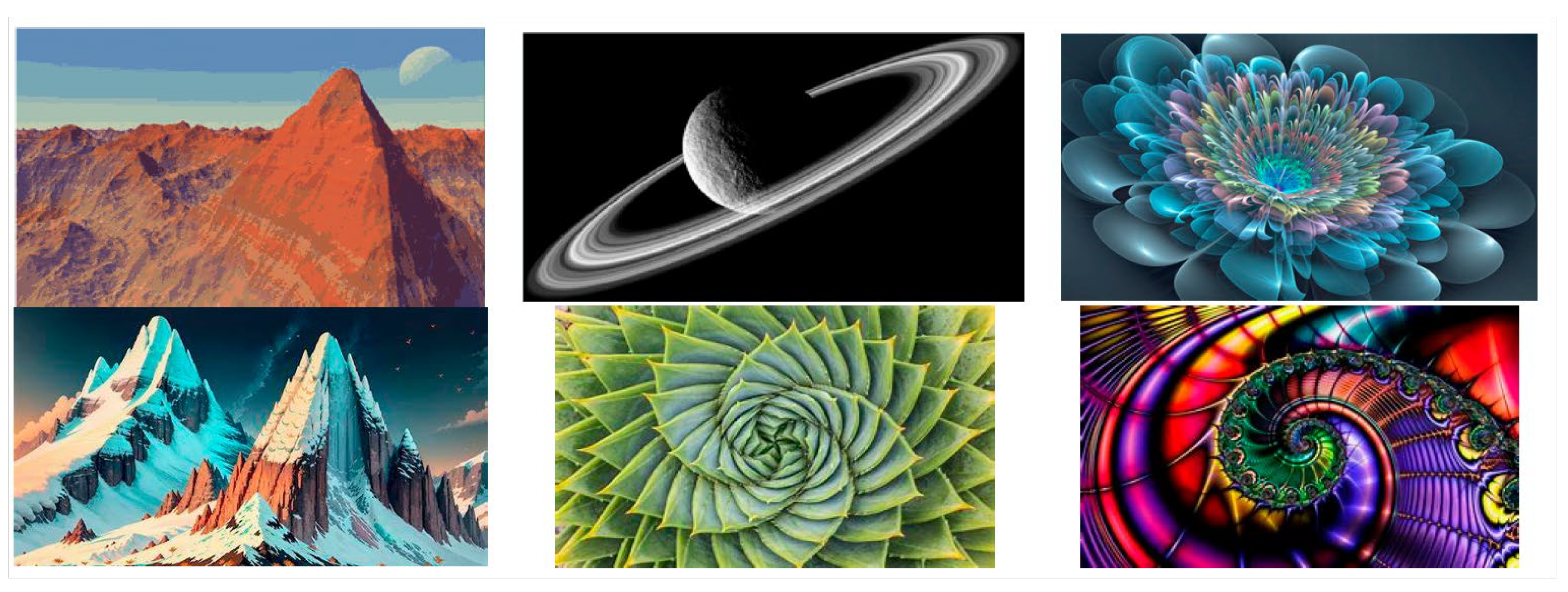

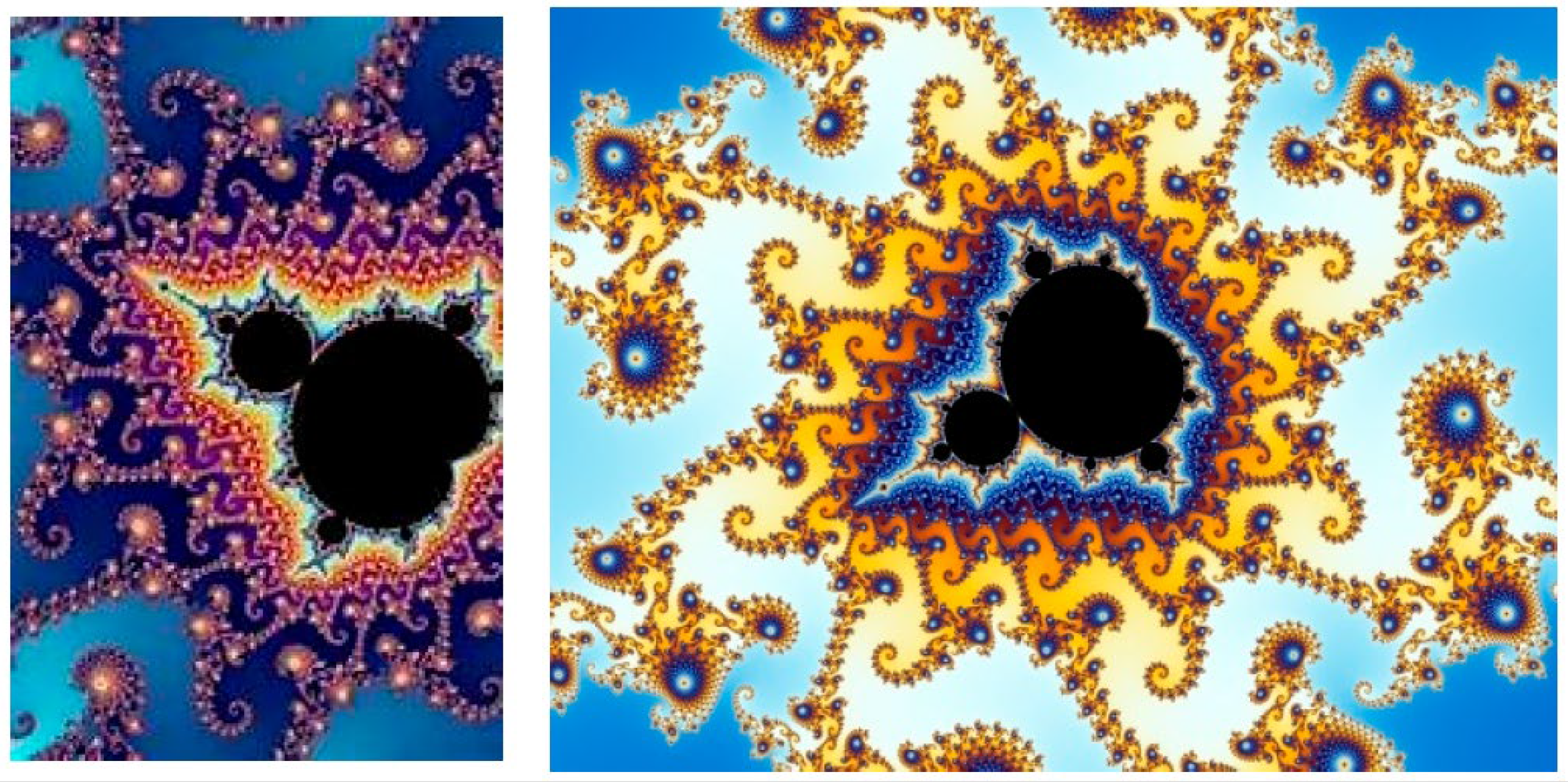

Theoretical Mathematics: The snowflake acts as a user-friendly “laboratory” for developing analytical tools(Bárány et al., 2023), such as fractal analysis, which can then be applied to more intricate and less understood fractal objects like the Mandelbrot set (as in

Figure 9 (c.f., Kupczynski, 2024)) or Julia sets (as in

Figure 10 (c.f., Kupczynski, 2024)).

In summary, the Koch snowflake’s seemingly simple design is quite misleading. It conceals deep and unresolved questions that connect pure mathematics with the physical sciences. The challenges surrounding its physical limits, optimal packing, and higher-dimensional forms guarantee that von Koch’s creation, over a century old, will keep inspiring and puzzling researchers. It serves as a reminder that even the simplest objects can hold endless complexity, paving the way for a future filled with discoveries.

References

- Aguiar e Oliveira Jr, H. (2022). Deterministic sampling from uniform distributions with Sierpiński space-filling curves. Computational Statistics, 37(1), 535-549. [CrossRef]

- Akhmet, M., Fen, M. O., & Alejaily, E. M. (2020). Dynamics with chaos and fractals. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Aravindraj, E., Nagarajan, G., & Ramanathan, P. (2023). Koch snowflake fractal embedded octagonal patch antenna with hexagonal split ring for ultra-wide band and 5G applications. Prog. Electromagn. Res. C, 135, 95-106. [CrossRef]

- Bárány, B., Simon, K., & Solomyak, B. (2023). Self-similar and self-affine sets and measures (Vol. 276). American Mathematical Society.

- Brown, C. A. (2024). Fractal-Related Multiscale Geometric Characterisation of Topographies. In Characterisation of Areal Surface Texture (pp. 151-180). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Bunimovich, L., & Skums, P. (2024). Fractal networks: Topology, dimension, and complexity. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 34(4). [CrossRef]

- Cahn, R. N., & Quigg, C. (2023). Grace in All Simplicity: Beauty, Truth, and Wonders on the Path to the Higgs Boson and New Laws of Nature. Simon and Schuster.

- Dally, W. J., Keckler, S. W., & Kirk, D. B. (2021). Evolution of the graphics processing unit (GPU). IEEE Micro, 41(6), 42-51. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P. (2020). Chaos, fractals, and dynamics. CRC Press.

- Golmankhaneh, A. K., & Bongiorno, D. (2024). Exact solutions of some fractal differential equations. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 472, 128633. [CrossRef]

- Hales, T. (2024). The Formal Proof of the Kepler Conjecture: a critical retrospective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.08032. arXiv:2402.08032.

- Henley, C. L. (1989). Ordering due to disorder in a frustrated vector antiferromagnet. Physical review letters, 62(17), 2056. [CrossRef]

- Husain, A., Nanda, M. N., Chowdary, M. S., & Sajid, M. (2022a). Fractals: an eclectic survey, part-I. Fractal and Fractional, 6(2), 89.

- Husain, A., Nanda, M. N., Chowdary, M. S., & Sajid, M. (2022b). Fractals: An eclectic survey, part II. Fractal and Fractional, 6(7), 379.

- Jeanjean, L., & Lu, S. S. (2022). On global minimizers for a mass constrained problem. Calculus of Variations and Partial Differential Equations, 61(6), 214.

- Kabashin, A. V., Kravets, V. G., & Grigorenko, A. N. (2023). Label-free optical biosensing: going beyond the limits. Chemical Society Reviews, 52(18), 6554-6585. [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, A. (2021). Fractal antennas and arrays: A review and recent developments. International Journal of Microwave and Wireless Technologies, 13(2), 173-197. [CrossRef]

- Kluth, Y. (2025). Fixed points of quantum gravity from dimensional regularization. Physical Review D, 111(10), 106010. [CrossRef]

- Koch, H. V. (1904). Sur une courbe continue sans tangente, obtenue par une construction géométrique élémentaire. Arkiv for Matematik, Astronomi och Fysik, 1, 681-704.

- Kupczynski, M. (2024). Mathematical Modeling of Physical Reality: From Numbers to Fractals, Quantum Mechanics and the Standard Model. Entropy, 26(11), 991. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I. A., & Bhat, A. H. (2022). Generalized Z-Entropy (Gze) and fractal dimensions. Appl. math, 16(5), 829-834.

- Mageed, I. A. (2023). Fractal Dimension (Df) of Ismail’s Fourth Entropy (with Fractal Applications to Algorithms, Haptics, and Transportation. In 2023 international conference on computer and applications (ICCA) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024a). The Fractal Dimension Theory of Ismail’s Third Entropy with Fractal Applications to CubeSat Technologies and Education. Complexity Analysis and Applications, 1(1), 66-78.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024b). Fractal Dimension of the Generalized Z-Entropy of The Rényian Formalism of Stable Queue with Some Potential Applications of Fractal Dimension to Big Data Analytics.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024c). Fractal Dimension (Df) Theory of Ismail’s Entropy (IE) with Potential Df Applications to Structural Engineering. Journal of Intelligent Communication, 3(2), 111-123. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I. A. (2024d). The Generalized Z-Entropy’s Fractal Dimension within the Context of the Rényian Formalism Applied to a Stable M/G/1 Queue and the Fractal Dimension’s Significance to Revolutionize Big Data Analytics. J Sen Net Data Comm, 4(2), 01-11.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024e). Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI preprints.

- Mageed, I. A., & Mohamed, M.(2023). Chromatin can speak Fractals: A review.

- Mageed, I.A. (2024f). Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI Preprints.

- Mageed, I.A. (2024g). The Mathematization of Puzzles or Puzzling Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202409.0609.v1. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024h). Let’s All Dance and Play Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202501.0437.v1. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024i). AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity Through Ismail A Mageed’s Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Preprints. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202501.0425.v1. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024j). Let’s All Dance and Play Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202501.0437.v1. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024k). AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity Through Ismail A Mageed’s Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Preprints. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202501.0425.v1. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I. A. (2024l). Fractal Dimension (Df) Theory of Ismail’s entropy (IE) with Potential Df applications to Smart Cities. J Sen Net Data Comm, 4(2), 01-10.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024m). Entropic Advancement To Education. Int J Med Net, 2(6), 01-10.

- Mageed, I. A., & Nazir, A. R. (2024). AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity through Ismail A Mageed’s Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Annals of Process Engineering and Management, 1(1), 33-85.

- Mageed, I. A.(2025a). The Hidden Poetry & Music of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals: Inspiring Students through the Art of Mathematics: A Guide for Educators. Eliva Press. https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-1450104825.

- Mageed, I.A. (2025b). The Hidden Dancing & Physical Education of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals. Eliva Press. https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-7724827898.

- Mageed, I. A. (2025c). Fractals Across the Cosmos: From Microscopic Life to Galactic Structures. MDPI Preprints.

- Mageed, I. A., & Li, H. (2025). The Golden Ticket: Searching the Impossible Fractal Geometrical Parallels to solve the Millennium, P vs. NP Open Problem. MDPI Preprints.

- Mohammad, U., Mohammad, H., Singh, V. N. N., & Mandal, B. P. (2025). Polyadic Cantor potential of minimum lacunarity: Special case of super periodic generalized unified Cantor potential. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical. [CrossRef]

- Peitgen, H. O., Jürgens, H., Saupe, D., & Feigenbaum, M. J. (2004). Chaos and fractals: new frontiers of science (Vol. 106, pp. 560-604). New York: Springer.

- West, B. J., & Mutch, W. A. C. (2024). On the fractal language of medicine. CRC Press.

- Yuan, A. C., & Crawford, N. (2024). Infinitely Stable Disordered Systems on Emergent Fractal Structures. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.17905.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).