Submitted:

05 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Spermatogonial Stem Cells (SSCs): Characteristics and Main Roles

3. Spermatogonial Stem Cells from Domestic Animal Species: Isolation and In Vitro Expansion Techniques

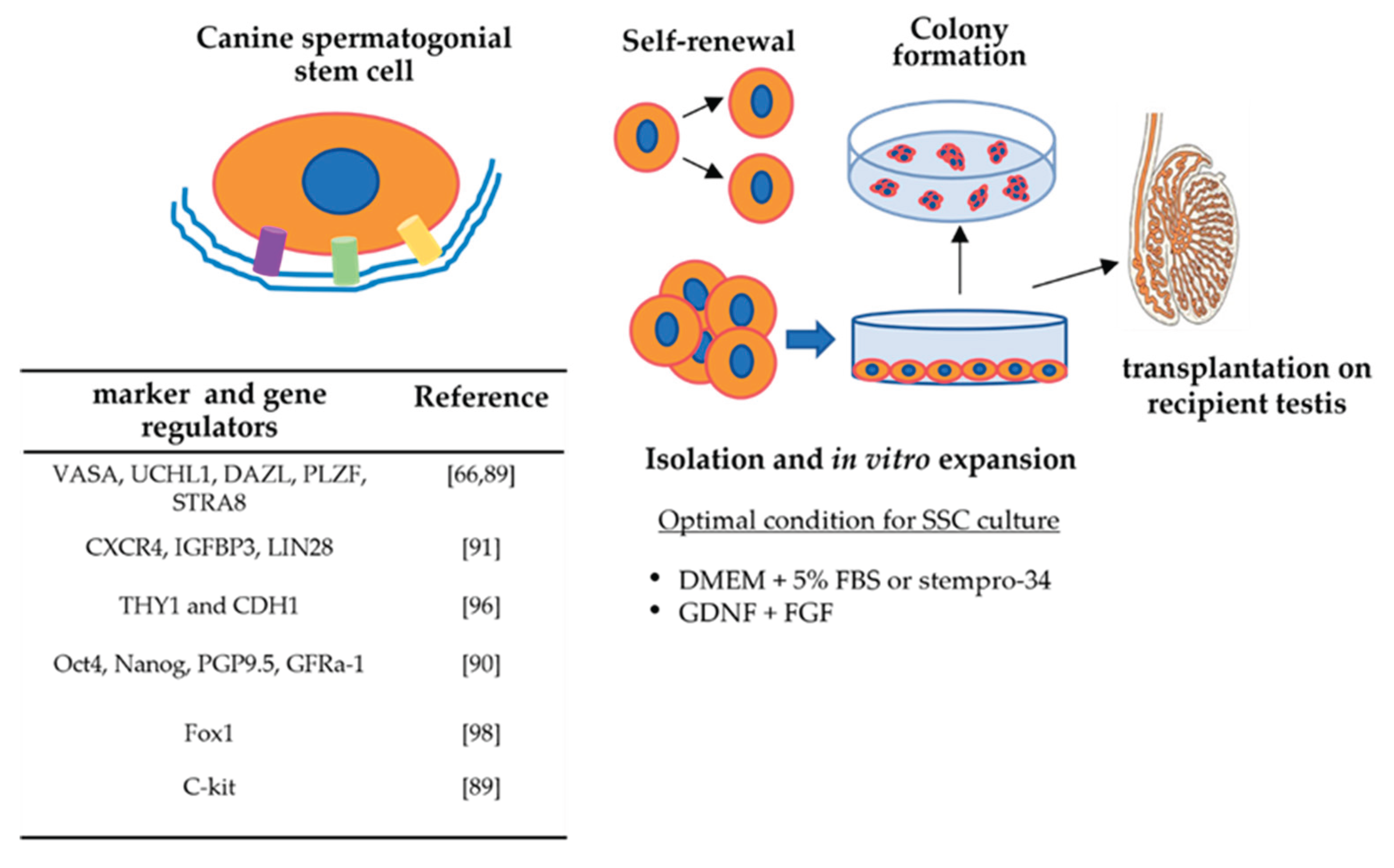

4. Canine Spermatogonial Stem Cells: Characteristics and Regulatory Factors

5. Potential Effects of Xenobiotic and External Factors on the Biology of Spermatogonial Stem Cells

6. Canine Spermatogonial Stem Cells and Pathophysiological Conditions Affecting Fertility

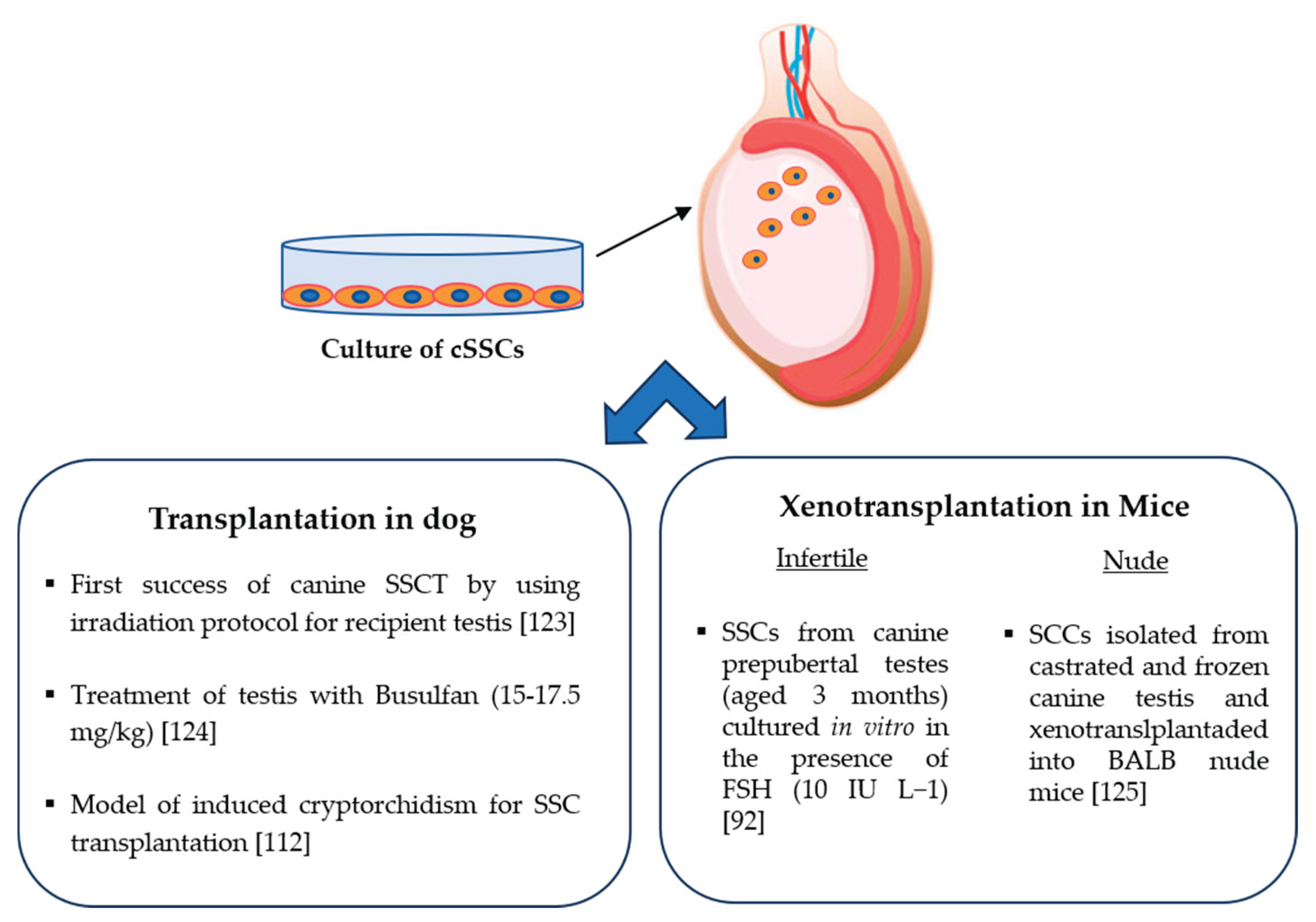

7. Canine Spermatogonial Stem Cells for Transplantation

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yoshida, S.; Sukeno, M.; Nabeshima, Y. A vasculature-associated niche for undifferentiated spermatogonia in the mouse testis. Science 2007, 317, 1722–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.L. , Wagers, A.J. No place like home: anatomy and function of the stem cell niche. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 9, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- La, H.M.; Hobbs, R.M. Mechanisms regulating mammalian spermatogenesis and fertility recovery following germ cell depletion. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 4071–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, P.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, D.; Nandi, S.K. Role of animal models in biomedical research: a review. Lab. Anim. Res. 2022, 38, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad-Toh et al. Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog, Nature 2005, 438, 803–819.

- Mirabella, N.; Pelagalli A., Liguori, G.; Rashedul, M.A., Squillacioti, C. Differential abundances of AQP3 and AQP5 in reproductive tissues from dogs with and without cryptorchidism, Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 228 106735.

- Squillacioti, C.; Mirabella, N.; Liguori, G.; Germano, G.; Pelagalli A. Aquaporins are differentially regulated in canine cryptorchid efferent ductules and epididymis. Animals 2021, 11, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, A.; Khramtsova, Y.; Yushkov, B. Mast cells as a component of spermatogonial stem cells' microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibtisham, F.; Awang-Junaidi, A.H.; Honaramooz, A. The study and manipulation of spermatogonial stem cells using animal models. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 380, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Oatley, M.J.; Law, N.C.; Robbins, C.; Wu, X.; Oatley, J.M. Proper timing of a quiescence period in precursor prospermatogonia is required for stem cell pool establishment in the male germline. Development 2021, 148, 194571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Sharma, M.; Nabeshima, Y.; Braun, R.E.; Yoshida, S. Functional hierarchy and reversibility within the murine spermatogenic stem cell compartment. Science 2010, 328, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Enomoto, H.; Suzuki, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Simons, B.D.; Yoshida, S. Mouse spermatogenic stem cells continually interconvert between equipotent singly isolated and syncytial states. Cell. Stem Cell 2014, 14, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.J.; De Falco, T. Role of the testis interstitial compartment in spermatogonial stem cell function. Reprod. 2017, 153, R151–R162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oatley, J.M.; Brinster, R.L. The germline stem cell niche unit in mammalian testes. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Grow, E.J.; Mlcochova, H.; Maher, G.J.; Lindskog, C.; Nie, X.; Guo, Y.; Takei, Y.; Yun, J.; Cai, L.; Kim, R.; Carrell, D.T.; Goriely, A.; Hotaling, J.M.; Cairns, B.R. The adult human testis transcriptional cell atlas. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, T.; Orwig, K.E.; Avarbock, M.R.; Brinster, R.L. Remodeling of the postnatal mouse testis is accompanied by dramatic changes in stem cell number and niche accessibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 6186–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahid, A.; Parviz, T.; Mansoureh, M.; Reza, Y. Effect of removal of spermatogonial stem cells (sscs) from in vitro culture on gene expression of niche factors in bovine. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2016, 8, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Lindahl M, Hyvonen ME, Parvinen M, de Rooij DG, Hess MW, Raatikainen-Ahokas A, Sainio K, Rauvala H, Lakso M, Pichel JG, Westphal H et al. Regulation of cell fate decision of undifferentiated spermatogonia by GDNF. Science 2000; 287(5457):1489–1493. 37.

- Hofmann, M.C.; Braydich-Stolle, L.; Dym, M. Isolation of male germ-line stem cells; influence of GDNF. Dev. Biol. 2005, 279, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, H.; Avarbock, M.R.; Brinster, R.L. Growth factors essential for selfrenewal and expansion of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 16489–16494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Laura, A.; Assif, N.; Gilbert, M.; Wijewarnasuriya, D.; Seandel, M. Enhanced fitness of adult spermatogonial stem cells bearing a paternal age-associated FGFR2 mutation. Stem Cell. Rep. 2014, 3, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.R.; Liu, Y.X. Regulation of spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal and spermatocyte meiosis by Sertoli cell signaling. Reprod. 2015, 149, R159–R167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, T.; Potter, S.J.; Williams, A.V.; Waller, B.; Kan, M.J.; Capel, B. Macrophages contribute to the spermatogonial niche in the adult testis. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oatley, J.M.; Avarbock, M.R.; Brinster, R.L. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor regulation of genes essential for self-renewal of mouse spermatogonial stem cells is dependent on Src family kinase signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25842–25851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oatley, M.J.; Kaucher, A.V.; Racicot, K.E. , Oatley J.M. Inhibitor of DNA binding 4 is expressed selectively by single spermatogonia in the male germline and regulates the self-renewal of spermatogonial stem cells in mice. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 85, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.E.; Kim, D.; Kaucher, A.; Oatley, M.J.; Oatley, J.M. CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling is required for the maintenance of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. J. Cell. Sci. 2013, 126, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, T.; Yang, H.; Mehmood, M.U.; Lu, Y.; Liang, X.; Yang, X.; Xu, H.; Lu, K.; Lu, S. The effects of growth factors on proliferation of spermatogonial stem cells from Guangxi Bama mini-pig. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2019, 54, 1574–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, P.; Tang, J.; Jiao, T.; Li, Y.; Ou, J.; Zou, D.; Li, M.; Mang, X.; Liu, J.; Ma, Y.; Wu, X.; Shi, J.; Chen, S.; He, M.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Miao, S.; Sun, F.; Wang, L.; Li, K.; Yu, J.; Song, W. Decoding the spermatogonial stem cell niche under physiological and recovery conditions in adult mice and humans. Sci Adv. 2023, 9, eabq3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Filipponi, D.; Gori, M. , Barrios, F.; Lolicato, F.; Grimaldi, P.; Rossi, P.; Jannini, E.A.; Geremia, R.; Dolci, S. ATRA and KL promote differentiation toward the meiotic program of male germ cells. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 3878–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlomagno, G.; van Bragt, M.P.; Korver, C.M.; Repping, S.; de Rooij, D.G.; van Pelt, A.M. BMP4-induced differentiation of a rat spermatogonial stem cell line causes changes in its cell adhesion properties. Biol. Reprod. 2010, 83, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, F.; Filipponi, D.; Campolo, F.; Gori, M.; Bramucci, F.; Pellegrini, M.; Ottolenghi, S.; Rossi, P.; Jannini, E.A.; Dolci, S. SOHLH1 and SOHLH2 control kit expression during postnatal male germ cell development. J. Cell. Sci. 2012, 125, 1455–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.E.; Racicot, K.E.; Kaucher, A.V.; Oatley, M.J.; Oatley, J.M. MicroRNAs 221 and 222 regulate the undifferentiated state in mammalian male germ cells. Development 2013, 140, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R.M.; Fagoonee, S.; Papa, A.; Webster, K.; Altruda, F.; Nishinakamura, R. , Chai, L.; Pandolfi, P.P. Functional antagonism between Sall4 and Plzf defines germline progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertz, M.J.; Wu, Z.; Gallardo, T.D.; Hamra, F.K.; Castrillon, D.H. Foxo1 is required in mouse spermatogonial stem cells for their maintenance and the initiation of spermatogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 3456–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Gao, C.; Lin, X.; Ning, Y.; He, W.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, D.; Yan, L.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Hossen, M.A.; Han, C. The microRNA miR-202 prevents precocious spermatogonial differentiation and meiotic initiation during mouse spermatogenesis. Development 2021, 148, 199799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Cui, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, C.; Du, L.; Tang, R. Qin, L.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, X., He, Q.; He, Z. Hsa-miR-1908-3p mediates the self-renewal and apoptosis of human spermatogonial stem cells via targeting KLF2. Nucl. Acids 2020, 20, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Chen, W.; Cui, Y.; Liu, B.; Yuan, Q.; Li, Z.; He, Z. miRNA-122-5p stimulates the proliferation and DNA synthesis and inhibits the early apoptosis of human spermatogonial stem cells by targeting CBL and competing with lncRNA Casc7. Aging 2020, 12, 25528–25546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zhou, F.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Qiu, Q.; Yu, X.; He, Z. miRNA-31-5p mediates the proliferation and apoptosis of human spermatogonial stem cells via targeting JAZF1 and Cyclin A2. Nucl. Acids 2019, 14, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, F.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, N.; Huang, Y.; Lei, C.; Chen, H.; Dang, R. MiRNAs expression profiling of bovine (Bos taurus) testes and effect of bta-miR-146b on proliferation and apoptosis in bovine male germline stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Mu, H.; Niu, Z.; Chu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Hua, J. miR-34c enhances mouse spermatogonial stem cells differentiation by targeting Nanos2. J. Cell. Biochem. 2014, 115, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.; Liang, J.; Mei, J.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Luo, J.; Tang, Y. , Huang, R., Xia, H., Zhang, Q.; Xiang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y. Sertoli cell-derived exosomal microRNA-486-5p regulates differentiation of spermatogonial stem cell through PTEN in mice. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 3950–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.H.; Mitchell, D.A.; McGowan, S.D.; Evanoff, R.; Griswold, M.D. Two miRNA clusters, Mir-17-92 (Mirc1) and Mir-106b-25 (Mirc3), are involved in the regulation of spermatogonial differentiation in mice. Biol. Reprod. 2012, 86, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Lin, X.; Du, T.; Xu, K.; Shen, H.; Wei, F.; Hao, W.; Lin, T.; Lin, X.; Qin, Y. , Wang, H., Chen, L., Yang, S.; Yang, J.; Rong, X.; Yao, K., Xiao, D., Jia, J.; Sun, Y. Targeted disruption of miR-17-92 impairs mouse spermatogenesis by activating mTOR signaling pathway. Medicine 2016, 95, e2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, K.; Sakai, M.; Kuroki, S.; Jo, J.I.; Hoshina, K.; Fujimori, Y.; Oka, K.; Amano, T.; Yamanaka, T.; Tachibana, M.; Tabata, Y.; Shiozawa, T.; Ishizuka, O.; Hochi, S.; Takashima, S. FGF2 has distinct molecular functions from GDNF in the mouse germline niche. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 10, 1782–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binsila, B.K. , Selvaraju, S. ; Ghosh, S.K.; Ramya, L.; Arangasamy, A.; Ranjithkumaran, R.; Bhatta, R. EGF, GDNF, and IGF-1 influence the proliferation and stemness of ovine spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. J. Assisted Reprod. Genetics 2020, 37, 2615–2630. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, N.; Laychur, A.; Sukwani, M.; Orwig, K.E.; Oatley, J.M.; Zhang, C.; Rutaganira, F.U.; Shokat, K.; Wright, W.W. Spermatogonial stem cell numbers are reduced by transient inhibition of GDNF signaling but restored by self-renewing replication when signaling resumes. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara, M.; Toyokuni, S.; Shinohara, T. cd9 is a surface marker on mouse and rat male germline stem cells. Biol. Reprod. 2004, 70, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, H.; Avarbock, M.R.; Brinster, R.L. Spermatogonial stem cells share some, but not all, phenotypic and functional characteristics with other stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6487–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, T.; Avarbock, M.R.; Brinster, R.L. beta1- and alpha6-integrin are surface markers on mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 5504–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, H.; Kokkinaki, M.; Jiang, J.; Dobrinski, I. , Dym, M. Isolation, characterization, and culture of human spermatogonia. Biol. Reprod. 2010, 82, 363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Schmidt, J.A.; Avarbock, M.R. Tobias, Y.W.; Carlson, C.A.; Kolon, T.F.; Ginsberg, J.P.; Brinster, R.L. Prepubertal human spermatogonia and mouse gonocytes share conserved gene expressionof germline stem cell regulatory molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009, 106, 21672–21677.66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dym, M.; Kokkinaki, M. , He, Z. Spermatogonial stem cells: mouse and human comparisons. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2009, 87, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oatley, J.M.; Avarbock, M.R.; Telaranta, A.I.; Fearon, D.T.; Brinster, RL. Identifying genes important for spermatogonial stem cell selfrenewal and survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 9524–9529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oatley, J.M.; Brinster, R.L. Regulation of spermatogonial stem cell selfrenewal in mammals. Ann. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2008, 24, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara, M.; Chen, G.; Morimoto, H.; Shinohara, T. CD2 is a surface marker for mouse and rat spermatogonial stem cells. J. Reprod. Develop. 2020, 66, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Jin, C.; Li, P.; Li, Y.; Tang, J.; Yu, Z.; Jiao, T.; Ou, J.; Wang, H.; Zou, D. , Li, M.; Mang, X.; Liu, J.; Lu,Y.; Li, K., Zhang, N., Miao, S.; Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Song, W. FOXC2 marks and maintains the primitive spermatogonial stem cells subpopulation in the adult testis. eLife 2023, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yin, P.; Li, H.; Gao, W.; Jia, H.; Ma, W. Transcriptome analysis of key genes involved in the initiation of spermatogonial stem cell differentiation. Genes 2024, 15, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Q.; Hu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, F.; Chen, J.; Zuo, Q.; Zhang, Y. miR-1458 is inhibited by low concentrations of Vitamin B6 and targets TBX6 to promote the formation of spermatogonial stem cells in Rugao Yellow Chicken. Poultry Sci. 2025, 104, 104583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.R.; Zhang, X.; Nagano, M.C. Establishment of a short-term in vitro assay for mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 77, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Persio, S.; Neuhaus, N. Human spermatogonial stem cells and their niche in male (in)fertility: novel concepts from single-cell RNA-sequencing. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadyar, F.; Spierenberg, G.T.; Creemers, L.B. , den Ouden, K.; de Rooij, D.G. Isolation and purification of type A spermatogonia from the bovine testis. Reproduction 2002, 124, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damyanova, K.B.; Nixon, B.; Johnston, S.D.; Gambini, A.; Benitez, P.P.; Lord, T. Spermatogonial stem cell technologies: applications from human medicine to wildlife conservation, Biol. Reprod. 2024, 111, 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.M.; Ren, Y.J.; Ren, F.; Li, Y.; Feng, T.Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, Y.Q.; Zhang, L.K.; Hu, J.H. Recent advances in isolation, identification, and culture of mammalian spermatogonial stem cells. Asian J. Androl. 2022, 24, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsila, K.B.; Selvaraju, S.; Ghosh, S.K. , Parthipan, S. ; Archana, S.S.; Arangasamy, A.; Prasad, J.K.; Bhatta, R.; Ravindra, J.P. Isolation and enrichment of putative spermatogonial stem cells from ram (Ovis aries) testis, Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 196, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nabulindo, N.W.; Nguhiu-Mwangi, J.; Kipyegon, A.N.; Ogugo, M.; Muteti, C.; Tiambo, C.; Oatley, M.J.; Oatley, J.M.; Kemp, S. Culture of kenyan goat (Capra hircus) undifferentiated spermatogonia in feeder-free conditions, Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 894075. [Google Scholar]

- Harkey, M.A.; Asano, A.; Zoulas, M.E. , Torok-Storb, B.; Nagashima, J., Travis, A. Isolation, genetic manipulation, and transplantation of canine spermatogonial stem cells: progress toward transgenesis through the male germ-line. Reproduction 2013, 146, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das Dipak Bhuyan, A.; Lalmalsawma, T. , Pratim Das, P., Koushik, S., Chauhan, M.S.; Bhuyan, M. Propagation of porcine spermatogonial stem cells in serum-free culture conditions using knockout serum replacement. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2023, 58, 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Binsila, B.K.; Selvaraju, S.; Ghosh, S.K.; Ramya, L.; Arangasamy, A.; Ranjithkumaran, R.; Bhatta, R. EGF, GDNF, and IGF-1 influence the proliferation and stemness of ovine spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 2615–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahare, M.; Kim, S.M.; Otomo, A.; Komatsu, K.; Minami, N.; Yamada, M.; Imai, H. Factors supporting long-term culture of bovine male germ cells. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2015, 28, 2039–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford-Guaus, S.J.; Kim, S. , Mulero, L.; Vaquero, J.M., Morera, C., Adan-Milanès, R., Veiga, A.; Raya, A. Molecular markers of putative spermatogonial stem cells in the domestic cat. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2017, 52, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wan, W. , Li, B., Zhang, X., Zhang, M., Wu, Z.; Yang, H. Isolation and in vitro expansion of porcine spermatogonial stem cells. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2022, 57, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.S.; Heidari, B. , Naderi, M.M.; Behzadi, B.; Sarvari, A.; Borjian-Boroujeni, S., Farab, M., Shirazi, A. Transplantation of goat spermatogonial stem cells into the mouse rete testis. Int. J. Anim. Biol. 2015, 1, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- You, F.W.; Bei, C.S.; Giang, D.D.; You, L.Q. , YanFei, D., XiaoCan, L.; Chan, L.; Ben, H.; DeShun, S. Isolation and identification of prepubertal buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) spermatogonial stem cells. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 29, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Indu, S.; Devi, A.N.; Sahadevan, M.; Sengottaiyan, J.; Basu, A.; Raj K, S.; Kumar, P.G. , Expression profiling of stemness markers in testicular germline stem cells from neonatal and adult Swiss albino mice during their transdifferentiation in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Minami, N.; Yamada, M.; Imai, H. Long-term culture of ndifferentiated spermatogonia isolated from immature and adult bovine testes. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2018, 85, 236–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Li, T.T.; Liu, Y.R.; Geng, S.S.; Luo, A.L.; Jiang,M.S.; Liang, X.W.; Shang, J.H.; Lu, K.H.; Yang, X.G. Transcriptome analysis revealed differences in the microenvironment of spermatogonial stem cells in seminiferous tubules between pre-pubertal and adult buffaloes. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2021, 56, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibtisham, F.; Tang, S.; Song, Y.; Wanze, W.; Xiao, M.; Honaramooz, A.; An, L. Optimal isolation, culture, and in vitro propagation of spermatogonial stem cells in Huaixiang chicken. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2024, 59, e14661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.M.J.; Avelar, G.F.; Lacerda, S.M.S.N.; Figueiredo, A.F.A.; Tavares, A.O.; Rezende-Neto, J.V.; Martins, F.G.P.; França, L.R. Horse spermatogonial stem cell cryopreservation: feasible protocols and potential biotechnological applications. Cell Tissue Res. 2017, 370, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarends, W.; Grootegoed, J. Molecular biology of male gametogenesis. Molecular biology in reproductive medicine New York, USA, 1999, 271-295.

- Kashfi, A.; Sani,R.N.; Ahmadi-hamedani, M. The beneficial effect of equine chorionic gonadotropin hormone (eCG) on the in vitro co-culture of bovine spermatogonial stem cell with Sertoli cells. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2019, 28, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navid, S.; Rastegar, T.; Baazm, M.; Alizadeh, R.; Talebi, A.; Gholami, K.; Khosravi-Farsani, S.; Koruji, M.; Abbasi, M. In vitro effects of melatonin on colonization of neonate mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2017, 63, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.Y.; Li, Q.; Ren, F.; Xi, H.M.; Lv, D.L.; Yu Li, Y.; Hu, J.H. Melatonin protects goat spermatogonial stem cells against oxidative damage during cryopreservation by improving antioxidant capacity and inhibiting mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 31, 5954635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, H.; Feyli, P.R.; Yari, K. , Wong, A.; Moghaddam, A.A. Low testosterone concentration improves colonisation and viability in the co-cultured goat spermatogonial stem cell with Sertoli cells. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2024, 59, e14729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarnejad, A.; Aminafshar, M.; Zandi, M. , Sanjabi, M.R.; Kashan, N.E. Optimization of in vitro culture and transfection condition of bovine primary spermatogonial stem cells. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 48, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushki, D.; Azarnia, M.; Gholami, M.R. Antioxidant effects of selenium on seminiferous tubules of immature mice testis. Zahedan J. Res. Med. Sci. 2015, 17, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, K.; Zandi, M.; Sanjabi, M.R.; Ghaedrahmati, A. In Vitro culture of ovine spermatogonial stem cells: effects of grape seed extracts and vitamin C. Gene Cell Tissue 2024, 11, e135750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.M.; Avelar, G.F.; De França, L.R. The seminiferous epithelium cycle and its duration in different breeds of dog (Canis familiaris). J. Anat. 2009, 215, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayomi, A.P.; Orwig, K.E. Spermatogonial stem cells and spermatogenesis in mice, monkeys and men. Stem Cell Res. 2018, 29, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieri, N.C.G.; De Souza, A.F.; Mançanares, A.C.F.; Roballo, K.; Casals, J.; Martins, D.D.S.; Ambrósio, C.E. Immunolocalization of proteins in the spermatogenesis process of canine. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2016, 52, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Lee, R.; Lee, W.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Chung, H.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, N.H.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, J.H. , Song, H. Identification and in vitro derivation of spermatogonia in beagle testis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e109963. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.Y.; Lee, R.; Park, H.J.; Do, J.T.; Park, C.; Kim, J.H.; Jhunc, H.; Leed, J.H.; Hure, T.; Song, H. Analysis of putative biomarkers of undifferentiated spermatogonia in dog testis. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2017, 185, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieri, N.C.G.; Mançanares, A.C.F.; de Souza, A.F.; Fernandes, H.; Diaza, A.M.G.; Bressan, F.F.; Roballo, K.C.S.; Casals, J.B.; Binelli, M.; Ambrósio, C.E.; dos Santos Martins, D. Xenotransplantation of canine spermatogonial stem cells (cSSCs) regulated by FSH promotes spermatogenesis in infertile mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Yan, G.J.; Ge, Q.Y.; Yu, F.; Zhao, X.; Diao, Z.Y.; Wang, Z.Q.; Yang, Z.Z.; Sun, H.X.; Hu, Y.L. FSH acts on the proliferation of type a spermatogonia via Nur77 that increases GDNF expression in the Sertoli cells. FEBS Lett. 2011, 15, 2437–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluka, P.; O’Donnell, L.; Bartles, J.R.; Stanton, P.G. FSH regulates the formation of adherens junctions and ectoplasmic specialisations between rat Sertoli cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 189, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, J.M.; McGuinness, M.P.; Qiu, J.; Jester, W.F.; Li, L.H. Use of in vitro systems to study male germ cell development in neonatal rats. Theriogenol. 1998, 49, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasimanickam, V.R. Kasimanickam, R.K. Sertoli, Leydig, and spermatogonial cells’ specific gene and protein expressions as dog testes evolve from immature into mature states. Animals 2022, 12, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reding, S.C.; Stepnoski, A.L.; Cloninger, L.W.; Oatley, J.M. THY1 is a conserved marker of undifferentiated spermatogonia in the pre-pubertal bull testis. Reprod. 2010, 139, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarnawa, E.D.; Baker, M.D.; Aloisio, G.M.; Carr, B.R.; Castrillon, D.H. Gonadal expression of foxo1, but not foxo3, is conserved in diverse mammalian species. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 88, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xue, X.; Fan, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Peng, M.; Zhou, J.; Cao, Z. Moderate hypoxia modulates ABCG2 to promote the proliferation of mouse spermatogonial stem cells by maintaining mild ROS levels. Theriogenol. 2020, 145, 149e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, M.; Choi, Y.; Yoon, M. Expression pattern of germ cell markers in cryptorchid stallion Testes, Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2024, 59, e14561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, W.J.; Deng, S.L.; Liu, X.; Jia, H.; Ma, W.Z. High temperature suppressed SSC self renewal through S phase cell cycle arrest but not apoptosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymperi, S.; Giwercman, A. Endocrine disruptors and testicular function. Metabolism 2018, 86, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R.M.; Skakkebaek, N.E. Are oestrogens involved in falling sperm counts and disorders of the male reproductive tract? The Lancet 1993, 341, 1392–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Guzman, A.; Moradian, R.; Cui, H.; Culty, M. In vitro impact of genistein and mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) on the eicosanoid pathway in spermatogonial stem cells. Reprod. Toxicol. 2022, 107, 150–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Shin, S.H.; Kim, S.M.; Jung, S.E.; Shin, B.J.; Ahn, J.S.; Lim, K.T.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, K.; Ryu, B.J. Bisphenol analogs downregulate the self-renewal potential of spermatogonial stem cells. World J. Mens Health 2025, 43, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanojević, M.; Sollner Dolenc, M. Mechanisms of bisphenol A and its analogs as endocrine disruptors via nuclear receptors and related signaling pathways. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 2397–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.S.; Won, J.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Jung, S.E.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, J.M.; Ryu, B.Y. Transcriptome alterations in spermatogonial stem cells exposed to bisphenol A. Anim. Cells Syst. 2022, 26, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharmalingam, M.D.; Matilionyte, G.; Wallace, W.H.B.; Stukenborg, J.B.; Jahnukainen, K.; Oliver, E.; Goriely, A.; Lane, S.; Guo, J.; Cairns, B.; Jorgensen, A.; Allen, C.M.; Lopes, F.; Anderson, R.A.; Spears, N.; Mitchell, R.T. Cisplatin and carboplatin result in similar gonadotoxicity in immature human testis with implications for fertility preservation in childhood cancer. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, D.; Hayes, G.; Heffernan, M.; Beynon, R. Incidence of cryptorchidism in dogs and cats. Vet. Rec. 2003, 152, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.W.Q.; Zhuang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Q.; Guo,Y.; Li, R.; Lu, X.; Cui, L.; Weng, J.; Tang, Y.; Yue, J.; Gao, S.; Hong, K.; Qiao, J.; Jiang, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z. Decoding the pathogenesis of spermatogenic failure in cryptorchidism through single-cell transcriptomic profiling, Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101709.

- Jhun, H.; Lee, W.Y.; Park, J.K.; Hwang, S.G.; Park, H.J. Transcriptomic analysis of testicular gene expression in a dog model of experimentally induced cryptorchidism. Cells 2022, 11, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.Y.; Lee, R.; Song, H.; Hur, T.Y.; Lee, S.; Ahn, J.; Jhun, H. Establishment of a surgically induced cryptorchidism canine recipient model for spermatogonial stem cell transplantation. Lab. Anim. Res. 2016, 32, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifarth, L.; Körber, H.; Packeiser, E.M.; Goericke-Pesch, S. Detection of spermatogonial stem cells in testicular tissue of dogs with chronic asymptomatic orchitis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1205064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, J.; Ko, J.A.; Mochizuki, H.; Funaishi, K.; Yamane, K.; Sonoda, K.-H.; Kiuchi, Y. Oxidative stress regulates expression of claudin-1 in human RPE cells. Open Life Sci. 2014, 9, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Hawkins, K.L.; DeWolf, W.C.; Morgentaler, A. Heat stress causes testicular germ cell apoptosis in adult mice. J. Androl. 1997, 18, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Persio, S.; Tekath, T.; Siebert-Kuss, L.M.; Cremers, J.F.; Wistuba, J.; Li, X.; Meyer Zu Horste, G.; Drexler, H.C.A.; Wyrwoll, M.J.; Tuttelmann, F. , Dugas, M.; Kliesch, S.; Schlatt, S.; Laurentino, S.; Neuhaus, N. Single-cell RNA-seq unravels alterations of the human sper matogonial stem cell compartment in patients with impaired spermatogenesis. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agoulnik, A.I.; Huang, Z.; Ferguson, L. Spermatogenesis in cryptorchidism. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 825, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, T.; Dobrinski, I.; Avarbock, M.R.; Brinster, R.L. Transplantation of male germ line stem cells restores fertility in infertile mice. Nat Med. 2000, 6, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arregui, L.; Dobrinski, I. Xenografting of testicular tissue pieces: twelve years of an in vivo spermatogenesis system. Reprod. 2014, 148, R71–R84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Aréchaga, J.M.; Avarbock, M.R.; Brinster, R.L. Transplantation of testis germinal cells into mouse seminiferous tubules. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1997, 41, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nagano, M.; Avarbock, M.R.; Brinster, R.L. Pattern and kinetics of mouse donor spermatogonial stem cell colonization in recipient testes. Biol. Reprod. 1999, 60, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrinski, I.; Avarbock, M.R.; Brinster, R.L. Transplantation of Germ Cells from Rabbits and Dogs into Mouse Testes, Biology of Reproduction 1999, 61, 1331–1339.

- Yeunhee, Kim; et al. , Production of donor-derived sperm after spermatogonial stem cell transplantation in the dog. Reprod. 2008, 136, 823–831. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, T.J.; Lee, S.H.; Ock, S.A.; Song, H.; Park, H.J.; Lee, R.; Sung, S.H.; Jhun, H.; Lee, W.Y. Dose-dependent effects of busulfan on dog testes in preparation for spermatogonial stem cell transplantation, Lab. Anim. Res. 2017, 33, 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.H.; Lee, W.Y., Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.H.; Do, J.T.; Park, C.; Kim, J.H., Choi, Y.S.; Song, H. Vitrified canine testicular cells allow the formation of spermatogonial stem cells and seminiferous tubules following their xenotransplantation into nude mice, Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21919.

| Factor | Role at level of SSC | Mechanism involved | Species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GDNF |

self-renewal self-renewal and proliferation |

Nanos2, Etv5, Lhx1, T, Bcl6b, Id1, and Cxcr4 |

mouse swine |

[20,24,25,26] [27] |

| IGF1, IGFBP7, NKCC1, and protein-tyrosine phosphatase | self-renewal and proliferation | CCL24, IGFBP7, and TEK | mouse and human |

[28] |

| retinoic acid | differentiation | Downregulation of GDNF expression activation of differentiation factors (BMP and SCF, SOHL1, SOHL2 |

mouse, rat |

[29,30,31,32] |

| PLZF transcription factor | self-renewal | SALL4 protein | mouse | [33] |

| FOXO1 transcription factor | self-renewal | PI3K-Akt signaling | mouse | [34] |

|

micro-RNAs miR-202 |

self-renewal | Influence of regulators such as STRA8 and DMRT6 | mouse | [35] |

| Hsa-miR-1908-3p | self-renewal |

Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) | human | [36] |

| miRNA-122-5p and miRNA-31-5p | proliferation | transcription factor CBL | human | [37,38] |

| bta-miR-146b | inhibit proliferation and promote apoptosis | n.d. | bovine | [39] |

| miR-34c | differentiation | Inhibition of the function of NANOS2 gene | mouse | [40] |

| miR-486-5p | differentiation | up regulating the expression of STRA8 and SYCP3 | mouse | [41] |

| miR-17-92 and miR-202 | spermatogenesis | Involvement of Bcl2l11, Kit, Socs3, and Stat3 | mouse | [35,42,43] |

| Animal | Optimal age for testis collection | Isolation method | Enrichment method | Factors added to the Culture Medium |

Evaluation of SSC proliferation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dog | 3–5 month old (pre-pubertal stage) | collagenase-only digestion | SG medium enriched with GDNF, FGF2, EGF, soluble GFRA1, LIF, and a laminin substratum | Note :the enriched cells can survive for several weeks | [66] | |

| pig | 1 month 7-15 days |

two-step enzymatic digestion two-step enzymatic treatment with collagenase,hyaluronidase type II, DNase I and trypsin-EDTA |

gelatin-coated differential plating (laminin and PLL) Sertoli cell feeder layer |

GDNF, FGF2, IGF1 and LIF EGF, epidermal growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growthfactor; GDNF, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; KSR, knockout serum replacement; |

25 days > 30 days |

[71] [67] |

| goat | 4 months | two-step enzymatic digestion |

percoll gradient 32% | LIF (10 ng ml-1), EGF (20 ng ml-1), bFGF (10 ng ml-1), GDNF |

15 days | [72] |

| sheep | two-step enzymatic digestion |

ficoll gradient (12%) and plating (laminin [20 μg/ml in combination with BSA] | GDNF (40ng/ml, EGF (20 ng/ml), and IGF1 (100 ng/ml) | 30 days | [68] | |

| calf | 5-7 months | three-step enzymatic digestion 1°(collagenase Type IV), 2° (collagenase Type IV + hyaluronidase), 3° trypsin and DNase I |

poly-L-lysine-coated method | knockout serum replacement (KSR) (15%) | > 2 months | [69] |

| chicken | 21 days | two-step enzymatic digestion |

differential plating |

2% FBS, GDNF (20 ng/ mL), bFGF (30 ng/mL), or LIF (5 ng/mL) |

7 days | [77] |

| buffalo | two-step enzymatic digestion |

FBS (2.5%) and GDNF (40 ng/mL) | days | [73] | ||

| cat | two-step enzymatic digestion |

gelatin-coated method |

GDNF (15 ng/mL) | 43 days | [70] | |

| horse | two-step enzymatic digestion |

percoll gradient (40%) | FBS (10%) | isolated SSCs cryopreserved after thawed demonstated metabolic activity as the fresh cells | [78] |

| Animals | Factor | Influence on aspect of SSCs biology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| mouse | melatonin (100 µM) |

cell viability improvement | [81] |

| goat | melatonin (1 μM) added to the culture medium | cell viability improvement during cryopreservation | [82] |

| goat | testosterone (60 μg/mL) |

improvement of cell viability and colonization | [83] |

| calf | equine chorionic gonadotropin hormone (eCG) (5 IU/ml) | cell colony formation improvement | [80] |

| calf | vitamin C (50 µg/mL) |

improvement of cell viability and colonization | [84] |

| sheep | vitamin C (50 g/mL) |

cell viability improvement | [86] |

| calf | α-tocopherol analogue (25 µg/mL ) |

improvement of cell viability and colonization | [85] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).