1. Introduction

Industry 4.0 is transforming the current industrial environment through digitizing production processes. This is accomplished by implementing full network integration in all phases of product life cycle management and real-time data exchange, moving the current industry toward digitally enabled smart factories [

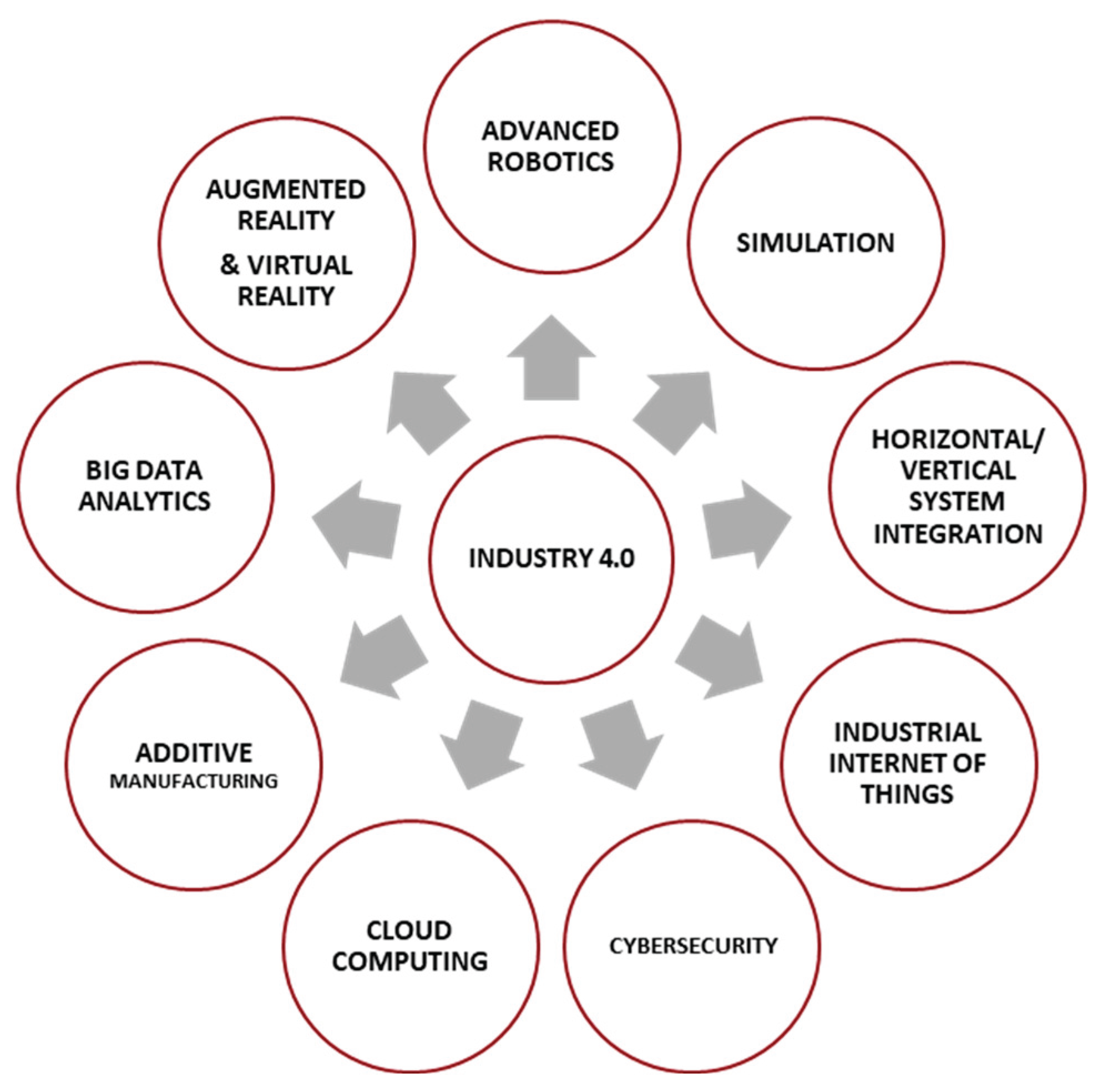

1]. Industry 4.0 is driven by nine fundamental technologies listed in

Figure 1. Immersive technologies such as Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) are among those nine transformative technologies that are enabling digital transformation towards the factory of the future [

2]. Virtual Reality (VR) is defined as “

the use of real-time digital computers and other specialized hardware and software to construct a simulation of an alternate world or environment, which is believable as real or true by the users” [

3]. Augmented Reality (AR) is a technique for “augmenting” the real world with digital things [

4]. The characteristics of AR systems as being able to geometrically match the virtual and real world and run interactively in real-time. AR must have three main characteristics: combining real and virtual worlds, real-time interaction, and registration in the 3D environment [

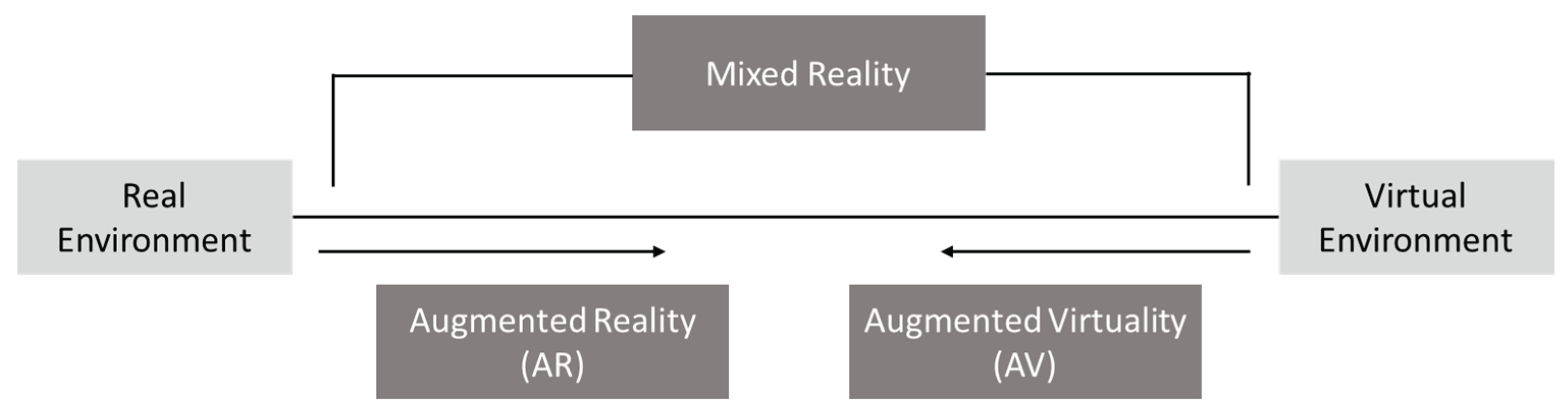

5]. The combination of a real environment scene and a virtual environment is known as Mixed Reality (MR). The term “Mixed Reality” refers to applications where

“real world and virtual world items are exhibited simultaneously within a single display, that is, anywhere between the extrema of the virtuality continuum [

4].

” While Augmented Reality (AR) takes place in a physical setting with virtual information added, Mixed Reality (MR) combines physical reality with virtual reality, allowing interaction between the physical and virtual world [

4]. For VR systems, the real and digital worlds are blended to fully immerse the user in a computer-generated environment. This includes a fully immersive display, often in the form of a headset, sensors to track user movement and orientation, controllers, or gloves for user interaction within the virtual environment, and a computational unit, often a PC or a dedicated system which renders the virtual world in real-time [

6,

7]. The Reality-Virtuality (RV) Continuum is depicted in

Figure 2 which illustrates the distinction between AR, VR, and MR [

4].

In recent years, there has been a substantial and rapid evolution of Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) technologies. These advancements have been recognized for their potential to enhance learning methodologies and improve task execution, particularly within contexts characterized by dynamic and adaptable requirements [

8]. AR and VR are leveraging the advantages of state-of-the-art technologies, like the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), and cloud computing making manufacturing processes smarter and more efficient [

9]. People can now interact with the manufacturing process efficiently, reducing the manufacturing processes’ downtime and leading to positive economic growth [

10].

The rapid evolution of manufacturing processes towards automation and efficiency, alongside the increasing integration of AR and VR technologies, serves as the primary motivation for this comprehensive review. Despite growing recognition of the potential benefits of AR and VR in manufacturing, there exists a notable research gap in synthesizing and critically evaluating recent technological advancements and applications within this context. This review aims to address this gap by systematically examining the current applications, state-of-the-art technologies, and challenges hindering widespread adaptation of AR and VR in manufacturing. By offering insights into emerging trends, this review aims to contribute to the advancement of AR and VR technologies in manufacturing applications.

This paper is organized into four sections. The proposal is introduced in

Section 1.

Section 2 explains the methodology for this literature review.

Section 3 discusses the findings of the literature review by answering the Research Questions (RQ). It highlights the detailed applications of AR and VR in the manufacturing industry, summarizes the key findings and emerging technologies providing the statistical analysis to find the research trends, and the challenges of implementing AR and VR technologies in manufacturing applications. In

Section 4 the literature review is concluded.

2. Review Methodology

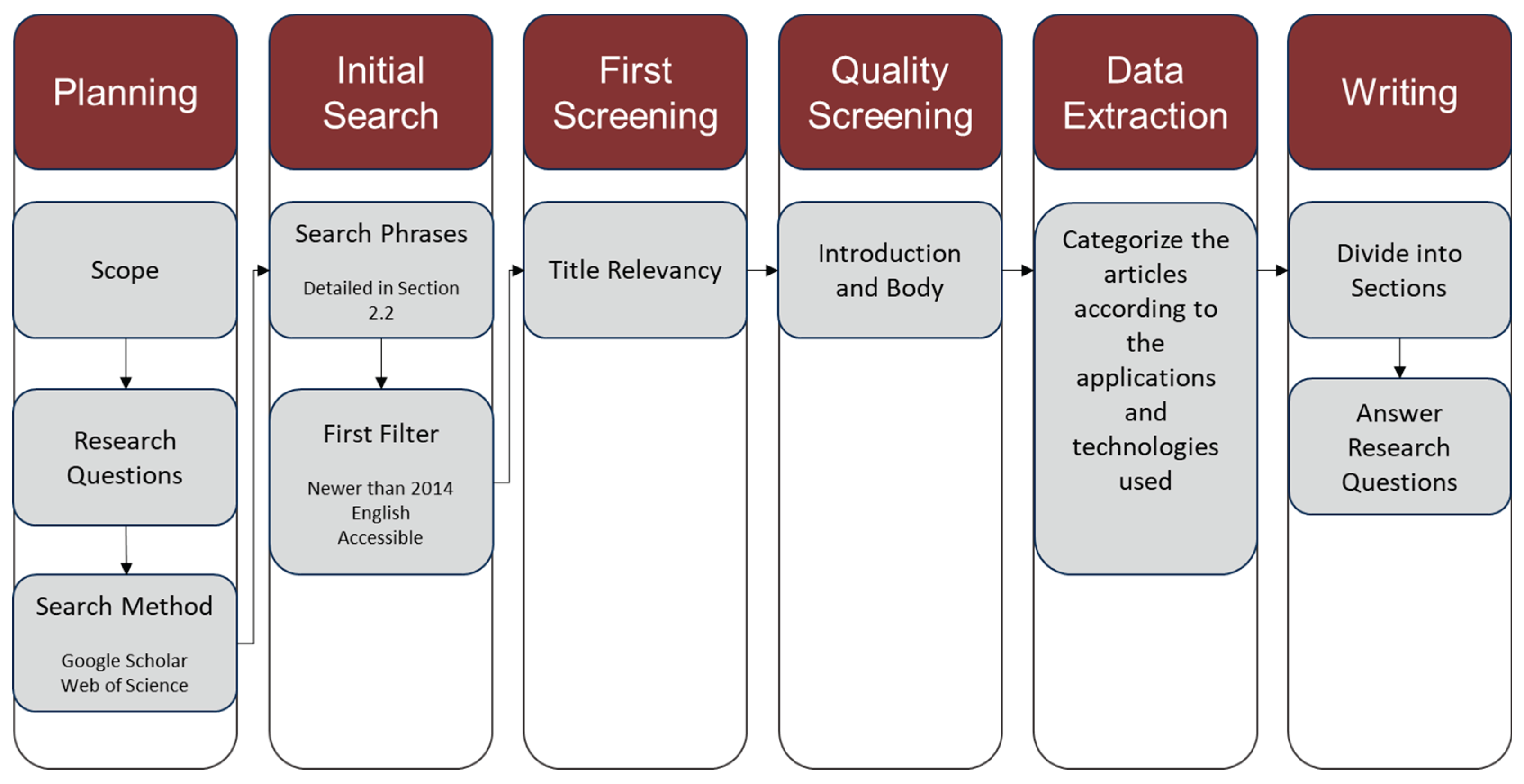

This paper utilizes a systematic approach to focus on cutting-edge research regarding AR and VR applications in manufacturing, spanning the period of 2015 to 2022. The primary goal was to collect key insights from relevant papers found in peer-reviewed journals and conferences. Through a thorough evaluation, the study aims to identify challenges in various aspects of AR/VR implementations for manufacturing and identify research trends. To conduct this literature review, the following steps were undertaken: planning the review methodology, defining the scope, conducting article searches, evaluating the identified articles, synthesizing relevant information, and analyzing the results [

11]. The steps of the review methodology are illustrated in

Figure 3.

2.1. Planning

The initial step involved formulating research questions to guide the research methodology, with a focus on identifying current technological trends and challenges of AR/VR technologies for manufacturing applications. The research questions are outlined in

Table 1. Subsequently, the Web of Science (

www.webofscience.com) database and Google Scholar (

www.scholar.google.com) search platform were used for gathering the peer-reviewed research articles as they are recognized for their reliability in providing peer-reviewed research articles.

2.2. Article Search

To collect research articles, a combination of search strings was used which are listed in

Table 2. For the initial search, the research articles that were newer than 2014 were included. Studies older than 2015 have not been included as these studies lose their relevance with the current technological advancement of AR/VR technologies. The statistics of the collected articles are listed in

Table 3. Only articles in English were included and commercial and repeated studies were excluded.

2.3. Initial Screening

In this step, titles and abstracts were screened to find the relevant papers that support the research questions. Articles related only to the AR/VR manufacturing applications were included. Relevant papers were also gathered by screening the references of the collected articles.

2.4. Quality Screening

To check the quality of the paper, the introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion of the collected papers were looked at to ensure the quality of the research and determine relevant research articles. The goal was to have a wide range of papers that would cover key topics of AR/VR. This would ensure that the information extracted from these articles would give an overview of all aspects of manufacturing.

2.5. Data Extraction

In this step, key elements from the research articles were extracted, and stored for further quantitative and qualitative analysis of the research.

2.6. Reporting

In this final stage, the extracted data was reviewed and reported in

Section 3. Different categories of papers and specific data were analyzed to get a detailed overview of the AR/VR-based manufacturing applications.

3. Results and Discussion

This section highlights key findings and insights derived from the reviewed literature. After a careful review of the collected articles, the answers to the research questions have been compiled.

3.1. RQ1: What Are the Current Applications of AR/VR in Manufacturing?

To begin addressing Research Question 1 (RQ1) on the current applications of AR/VR in manufacturing, the literature review identifies the common applications where AR/VR is used within the manufacturing sector.

3.1.1. Maintenance Applications

Maintenance, a critical facet of manufacturing, is important for keeping production lines working smoothly and keeping product quality. A large portion of research focuses on this area as it can increase costs significantly and impact safety [

12]. AR and VR have emerged as potent tools in the domain of maintenance, offering substantial potential for cost reduction by streamlining troubleshooting procedures, expediting access to documentation, and pinpointing malfunction locations. A study documented in [

2] underscores the advantages of graphical representations over text-based information, as they facilitate quicker and more effective information processing. Using Augmented Reality (AR) instructions for maintenance has been proven to be effective, with real-world evidence showing it can cut maintenance time for industrial machinery by up to 30% [

10]. An AR-based maintenance operation in which symbols/arrows are used to show screw locations during repair is depicted in

Figure 4. Many of the papers found in maintenance applications showed the use of HMDs as they allowed both hands to be free during repair. Some applications, however, use HHD for some troubleshooting and diagnostic scenarios. This could involve looking into machines or walls where equipment and parts aren’t necessarily visible.

3.1.2. Assembly Applications

AR/VR in the field of assembly applications is one of the most widely used. Studies show that AR/VR solutions, when compared to paper-based instructions, are superior in assembly tasks, demonstrating a decrease in both times to complete and error rate [

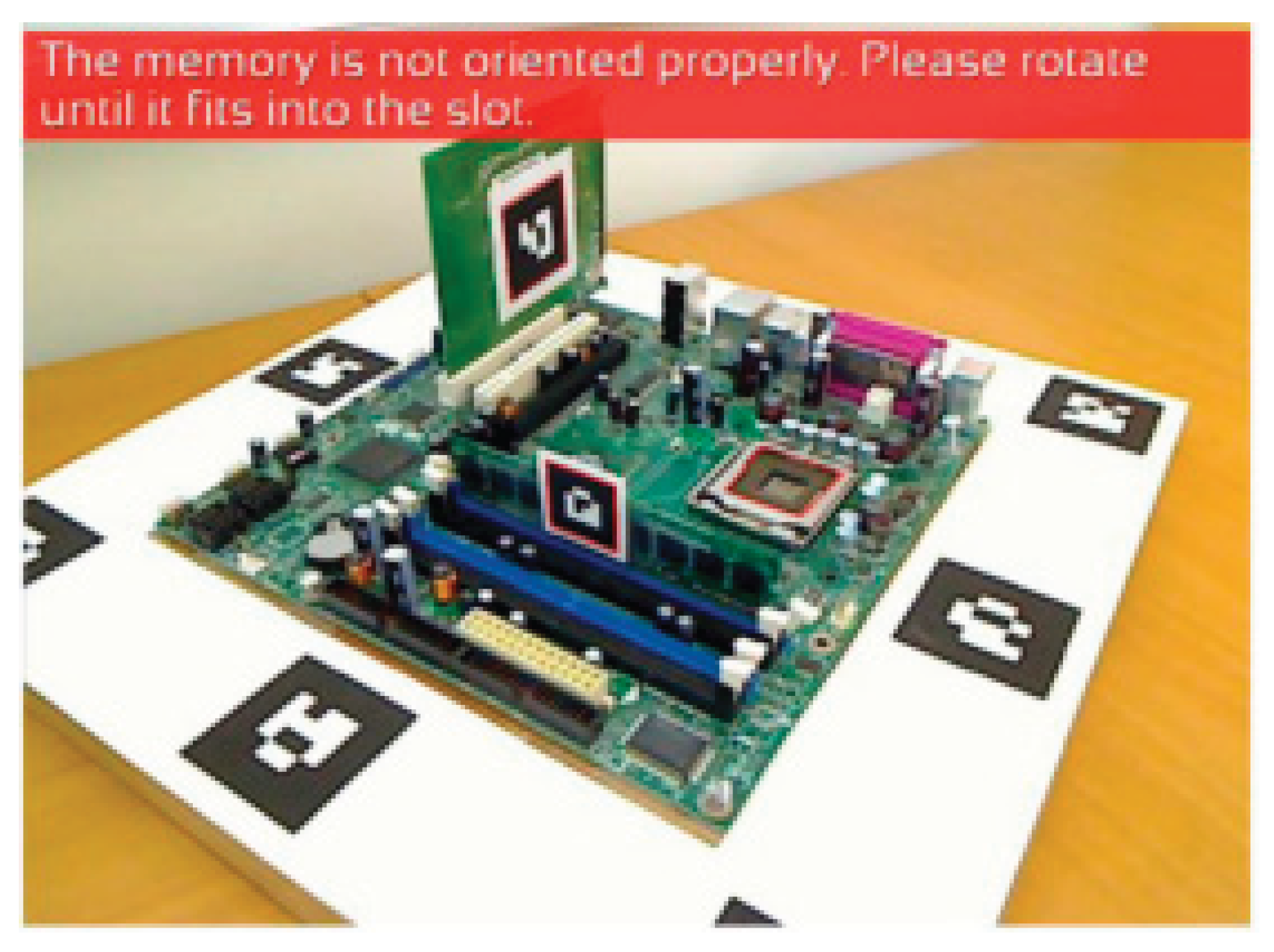

13]. Moreover, they exhibit a larger decrease in these aspects as the tasks become more complex. Participants in the study who were not experienced in analyzing complex isometric drawings were able to understand them for their assembly task. The learning curve also steepened compared to paper-based instructions showing a decrease in time for users to become familiar with a reoccurring task. Studies also showed that when comparing experts and untrained workers with assembly tasks, both categories of workers increased in their efficiency and decreased in errors. An example of an AR-based assembly application is shown in

Figure 5.

3.1.3. Operations Applications

Shop floor operators show a lot of movement on the floor of a manufacturing plant, moving to different tasks, to gather materials, or to get information. Operation applications focus on decreasing the time of movement of operators around the plant and customizing routes to be the most efficient [

2]. They also describe the planning method in manufacturing as well as the setup of machines during production change [

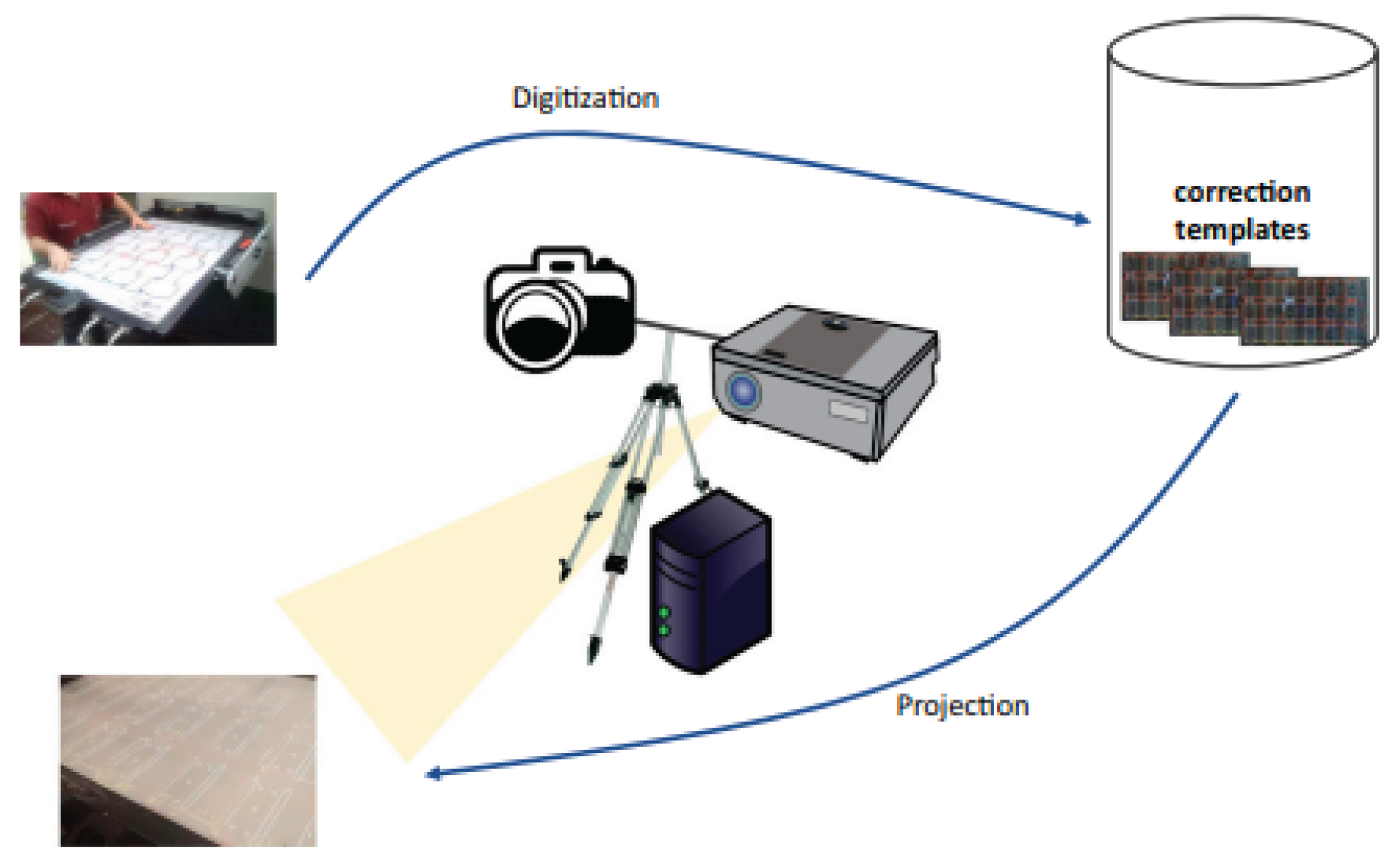

14]. The use of a projection-based (spatial AR) system shown in

Figure 6 is implemented in a die-cutting station to digitize and display correction templates on the matrix. Originally each product die cutter combination would require a unique correction template, meaning a large physical storage of collection templates. The proposed solution eliminates this by digitizing the correction templates and projecting them onto the matrix. The operator now only has to look up the template on the computer and display it.

All of the forms of visualization have been seen in operations scenarios. This is due to the extent of varying environments and work that operators have to do. They can certainly be specialized by the operation being done.

3.1.4. Training Applications

Training systems play a pivotal role in modern workplaces, alleviating the time constraints faced by trainers and enhancing the overall learning experience. AR and VR have gained prominence in these contexts due to their ability to engage users effectively, thereby amplifying learning performance and motivation [

15]. It is essential to note that the term ‘training’ encompasses the concepts discussed in the preceding sections, all of which contribute to the comprehensive training of new employees. Training applications not only aim to familiarize users with AR/VR interfaces but also strive to foster self-sufficiency to the point where AR/VR becomes unnecessary. Additionally, these applications facilitate the seamless integration of tasks regardless of the worker’s skill level. In manufacturing industries, where onboarding and training processes for new employees can span several weeks, such systems become indispensable. By reducing the time required by already trained employees, they allow these individuals to focus on their core responsibilities.

3.1.5. Product Design Applications

Product design and prototyping are integral parts of manufacturing processes. The success of any design project depends on effective prototyping [

16,

17]. Designers have been predominantly using Computer-Aided Design (CAD) tools since the 1990s for the design, development, prototyping, and simulation of new products [

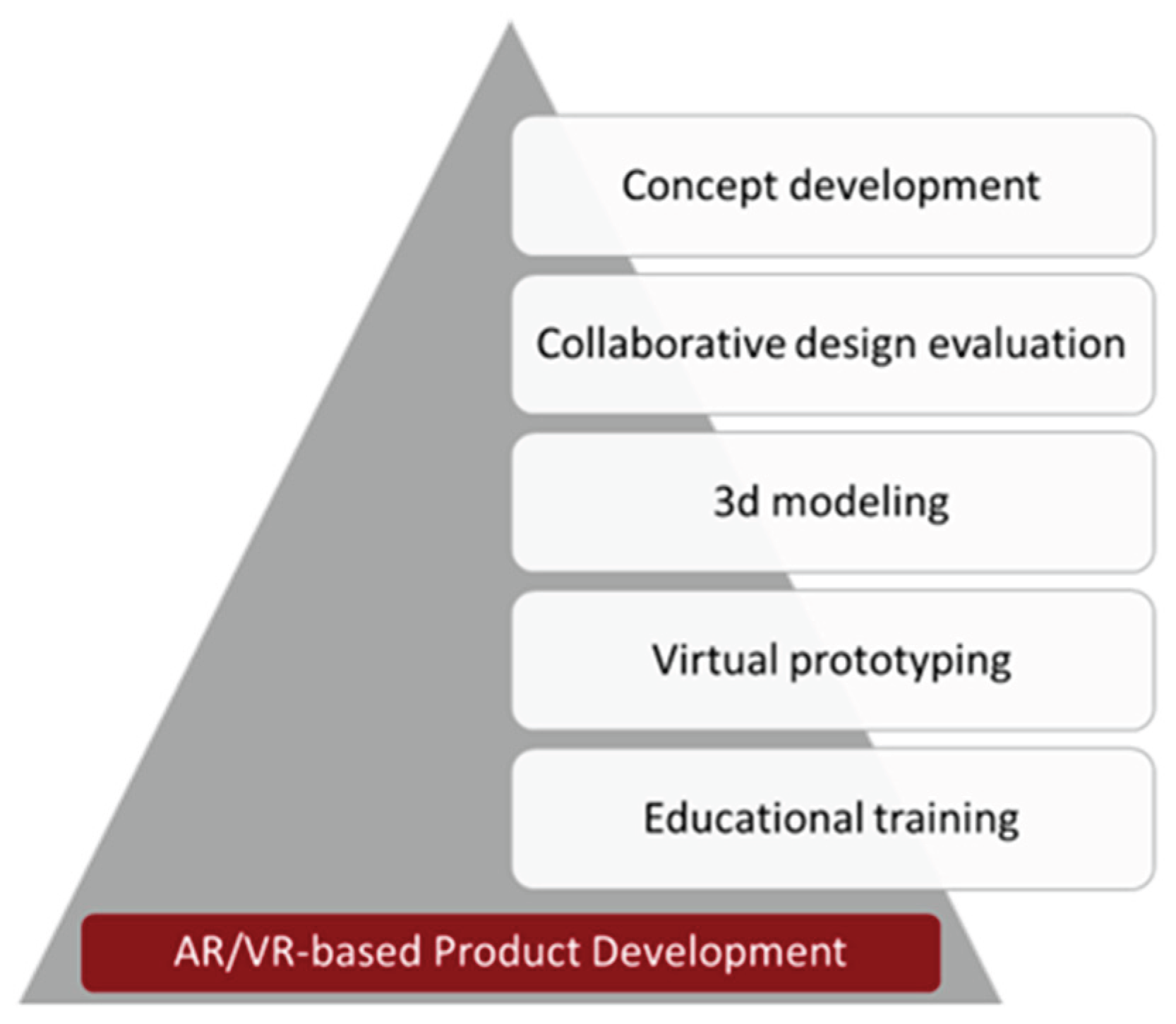

18]. With the technological maturity of Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) hardware and software, designers are adopting AR/VR technologies as extensions of the CAD tools for better visualization and realization of the product design. Using these technologies product designs are overlaid onto the physical setup or users can interact with the product design and assemblies in an immersive environment using AR/VR devices making the design process more realistic and collaborative. AR/VR can be incorporated into every stage of the product design lifecycle [

18] (

Figure 7). AR/VR can effectively be used for remote design collaboration by bringing different remote users into one immersive platform. In one study, authors utilized a model-based definition approach and AR to develop an industrial product inspection using 3D CAD software and product manufacturing information (PMI) data transfer methods [

19]. Despite the potential significant benefits of utilizing AR/VR in design applications, AR/VR technologies are not adopted in a wide range of design applications. The authors proposed a Double Diamond design model to address this issue by utilizing systematic AR use case identification, criteria catalog for appropriate AR device selection, and recommendation of modular software architecture for efficient customization and data integration within enterprise IT frameworks [

20].

3.1.6. Quality Control Applications

Continuous monitoring of the production process and the evaluation of product quality is an essential part of the manufacturing process. Quality control helps manufacturers identify and address quality-based issues in real-time and helps to enhance the consistency of the process, reduce product defects, and improve overall production efficiency. Computer vision technology, sensor-based defect detection, and non-destructive testing are general technologies that are predominantly used for defect detection. AR and VR technologies are seen to be emerging in the area of quality control and visualization. Several research studies have been conducted to incorporate AR and VR technologies into manufacturing. The authors of [

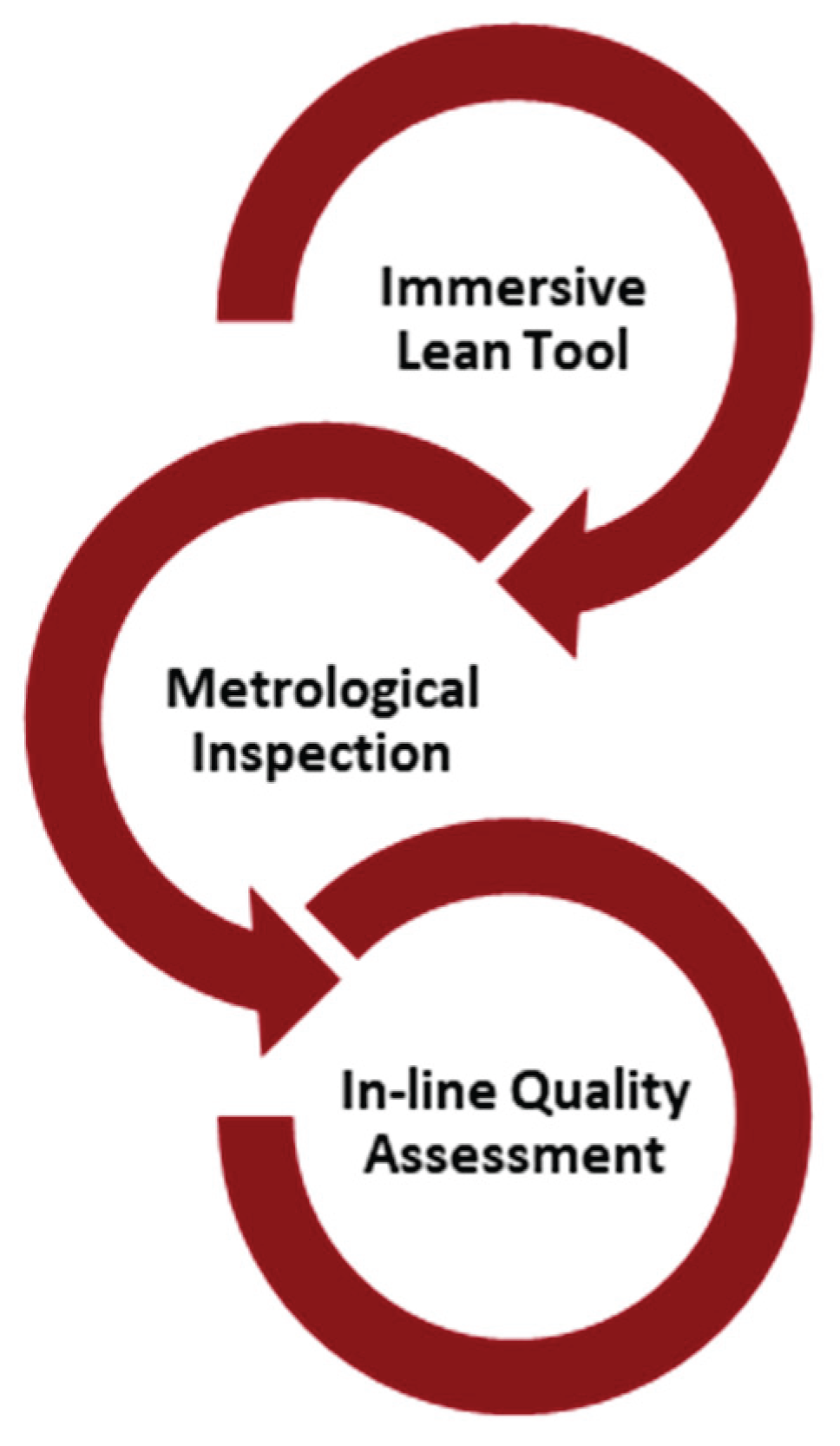

21] identified the three main areas of AR/VR application, depicted in

Figure 8, for the quality control in manufacturing: immersive lean tool, metrological inspection, and in-line quality assessment. The authors of [

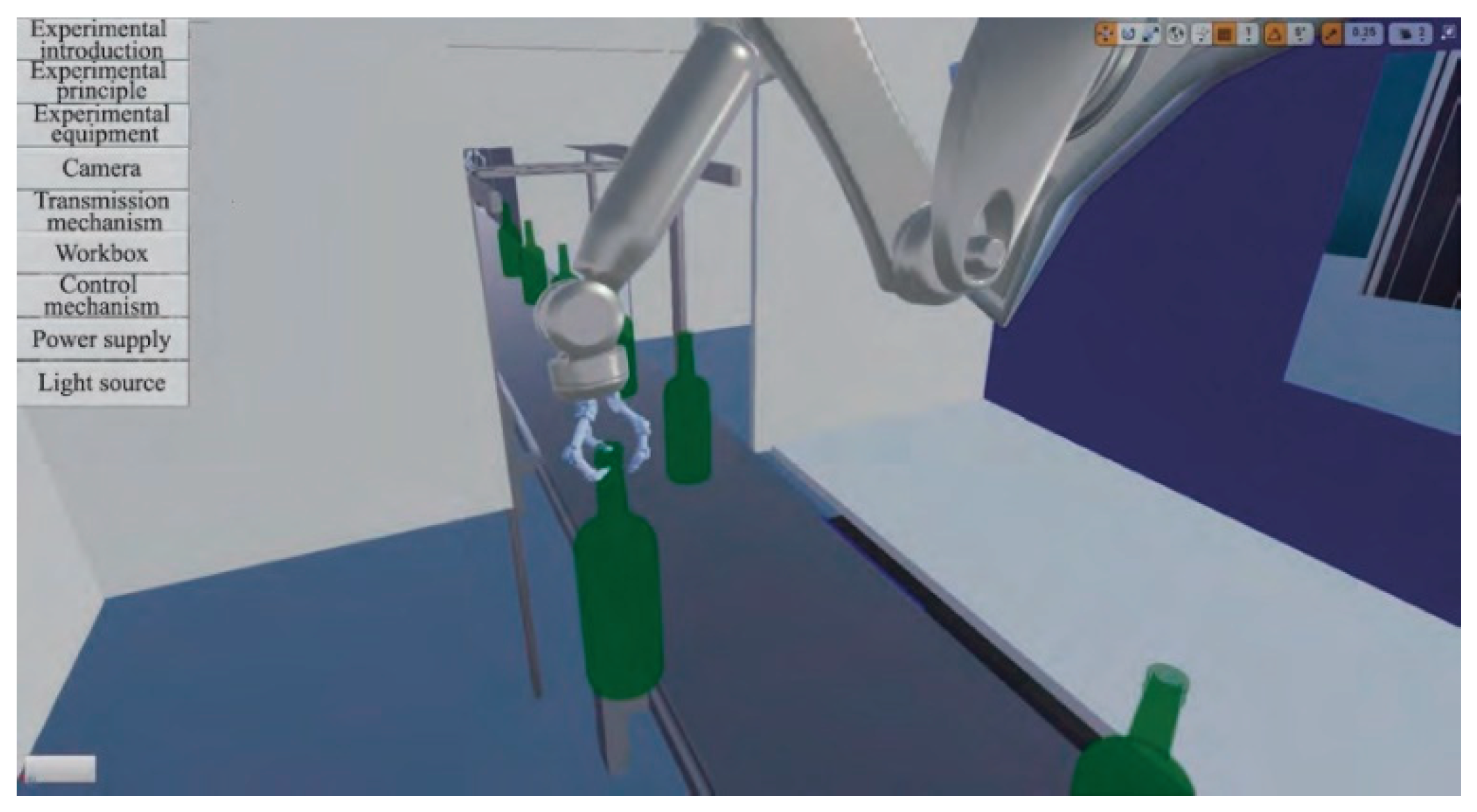

22] utilized 3DS MAX and Unreal Engine 4 to develop a virtual simulation shown in

Figure 9 for teaching machine learning-based beer bottle defect detection, encompassing bottom, mouth, and body defects and the system was evaluated with traditional experiments, 40 junior students preferred the immersive and interactive virtual experiment, highlighting its effectiveness in the learning process. In one study, researchers employed AR technology to real-time monitor polished surface quality in a SYMPLEXITY robotic cell with an ABB robot, visualizing metrological data onto the parts to time to check if the quality reached the required specifications [

23]. Some AR/VR-based quality control applications in manufacturing are listed in

Table 4.

In summary, the major applications of AR/VR in manufacturing encompass maintenance, assembly, operations, training, product design, and quality control, each demonstrating substantial benefits in improving efficiency, reducing errors, and enhancing overall productivity. However, the potential of these technologies extends beyond these core areas to include inventory management, supply chain optimization, customer engagement, and more.

3.2. RQ2: What Are the State-of-the-Art Technologies Used in AR/VR Applications in Manufacturing?

Addressing Research Question 2 (RQ2) regarding the state-of-the-art technologies used in AR/VR applications within manufacturing requires a comprehensive exploration of cutting-edge tools and platforms utilized in the industry. This investigation delves into key components, hardware, and software that are vital for the implementation of AR/VR technologies across various manufacturing processes.

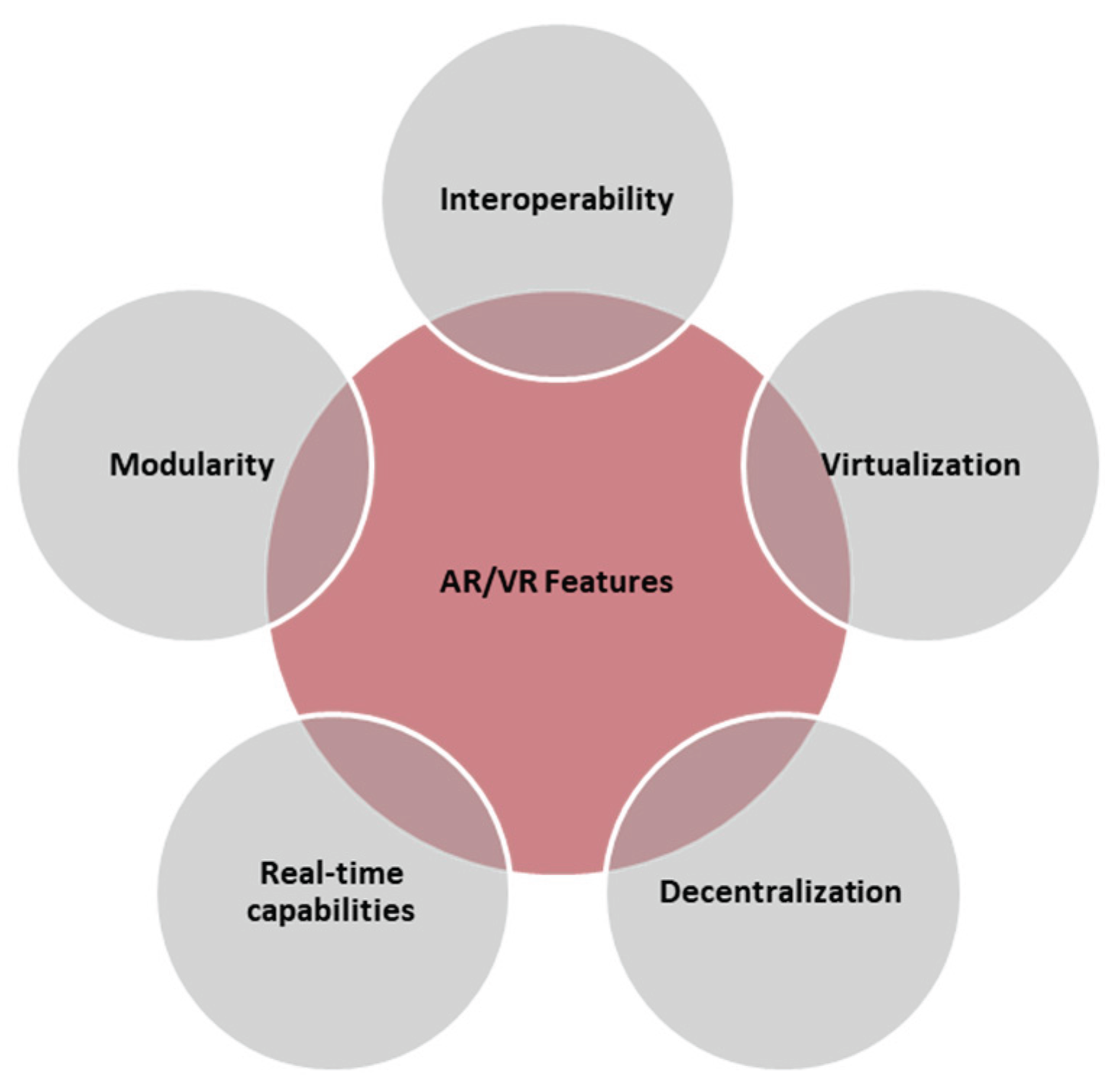

There are several aspects of AR/VR applications and devices that have been recognized by most papers to be necessary for creating a system that incorporates smart manufacturing paradigms. Several reoccurring ideal features depicted in

Figure 10 can be seen for AR/VR systems: interoperability, virtualization, decentralization, real-time capabilities, and modularity [

24,

25]. Interoperability is one of the largest contributors to smart manufacturing, allowing communication between the user and the machines in the manufacturing environment through the Internet of Things (IoT) and other industry standards. Standardization of these devices is also crucial for the system to be robust throughout multiple scenes [

10]. Virtualization is necessary for calibrating devices and creating the digital environment and simulation models using Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS). CPS can use this information to monitor processes that are happening in real-time and notify the user of changes in the scene. Decentralization enables easy access to diverse work instructions, providing users with specific information and procedures without manual searching, saving valuable time [

24,

25]. Real-time capabilities are especially important as it is crucial for the users to have up-to-date information on how the status of machines and operations are changing as well as updating technical machine data to keep plant records current. This also applies to the use of the application as tracking technologies are needed to process data in real-time. Finally, the modularity of the application keeps it flexible to changes in the environment and allows the system to adapt to specific scenarios in the scene. This means that documentation on new processes and procedures needs to be up to date and modularized to specific use cases [

24].

There are certain key components of AR/VR technologies that are required for the implementation of AR/VR-based applications in manufacturing. In this section, the key components specifically hardware, and software utilized in AR/VR-based manufacturing applications are reviewed and discussed at length.

3.2.1. Hardware Used in AR Applications

The components of an AR hardware system include tracking devices, haptic and force feedback rendering devices, displays, and sensors [

26]. AR display/visualization devices can be divided into 3 types: Head Mounted Device (HMD), Handheld Display (HHD), and Spatial Display (SD).

An HMD is a display device that is worn on the head or as a component of a helmet, and it has a display optic in front of one (monocular HMD) or both eyes (binocular HMD). In AR applications, HMDs are frequently used because the eye-level display enables users to experience the AR scene hands-free. HMD devices are the preferred choice for AR applications in manufacturing. They offer hands-free operation which enables the workers to interact with manufacturing systems and access virtual overlayed information. Additionally, for AR systems HMDs overlay real-time data directly onto the physical world optimizing the efficiency and accuracy of the manufacturing operation. There are many commercially available AR visualization devices in the market.

Handheld Display (HHD) enables users to visualize the AR environment when the display is held in reference to a specific environment [

27]. These can include tablets and cellphones that have screens and cameras available to receive and display data.

Spatial Displays are mostly projection-based displays that do not require users to wear head-mounted displays and instead project information into the actual surroundings [

26]. Spatial Displays in manufacturing can project assembly instructions and quality inspection details directly onto parts. Additionally, they enhance training and safety by overlaying crucial data and guidelines directly onto the shop floor or machinery [

28].

3.2.2. Tracking Systems for AR Applications

In manufacturing applications, various tracking systems are employed, including marker-based, model-based, and feature-based tracking. Among these, marker-based tracking has widespread popularity due to its robustness and ease of setup. Model and feature-based tracking methods are also employed, often in conjunction with marker-based tracking. These tracking systems enable the augmented reality (AR) headset to precisely determine the location of objects within the environment and establish the spatial positioning of the AR system itself [

10]. Notably, these tracking systems can be integrated in a hybrid fashion, allowing for more versatile and accurate tracking solutions.

Marker-based tracking involves the utilization of external visual aids, such as ArUco markers or Infrared (IR) markers, to precisely determine the spatial position of objects. However, these tracking systems come with distinct advantages and disadvantages. Marker-based tracking stands out as a highly reliable solution due to its minimal external processing requirements, resulting in low-latency performance. Additionally, these markers remain stationary, mitigating the need for the AR application to rely on other reference points or external data sources. For marker-based tracking to function effectively, the markers must remain within the field of view of the camera, ensuring the viability and accuracy of the tracking system [

29].

Model-based tracking utilizes CAD models to locate components in the environment, leveraging prior knowledge of object shapes and appearances for AR interpretation. By placing markers on CAD models during setup, the system can accurately track and display virtual information, and when combined with digital twins, it provides a highly accurate representation of the work environment. [

2]. These models can be used with a deep learning program to evaluate different forms of the object which is especially useful when interacting with objects that move like robots.

Feature-based tracking brings objects into the digital domain by considering their points, using the object’s features as markers, similar to marker-based tracking. It relies on a point cloud model combined with CAD models to identify and track objects, providing a way to determine an object’s identity and follow its movements [

30].

3.2.3. Hardware Used in VR Applications

Virtual Reality (VR) applications require a range of hardware to deliver immersive experiences. Various types of visualization displays are used for VR applications such as HMDs like the Meta Quest, HHDs like Tablets or PCs, and some Personal Computers are also used for simulation and digital twin applications. Different tracking sensors such as camera, motion, and gaze are used to track the headset, controllers, and human actions. Haptic systems are also an important part of the VR hardware system. Input devices range from motion controllers to eye-tracking modules. Positional tracking encompasses sensors and treadmills, while haptic feedback offers tactile sensations. Lastly, the VR experience can be powered by VR-ready PCs or wearable backpack computers, complemented by spatial audio hardware for sound immersion [

26,

31].

3.2.4. Software Used in AR/VR Applications

The field of AR/VR is continuously evolving with new software tools and platforms. Game engines are often used to develop AR/VR applications as they use extensive computation to overlay virtually generated information into 3D spaces. Unity 3D and Unreal engine are two of the most popular game engines for developing AR/VR applications [

32]. Among those two, Unity 3D is mostly adopted by developers to build AR/VR applications due to its cross-platform capabilities. Along with these game engines developers also use different AR/VR libraries for the application development. AR libraries such as Vuforia, ARToolKit, ARCore, ARKit, Mixed Reality Tool Kit (MRTK), and Wikitude are widely implemented. Vuforia is one of the widely used AR libraries for AR application development, ARKit is used for iOS-based AR application development, and ARCore is used for developing AR applications on Android devices. Wikitude is a cross-platform AR library. The MRTK is necessary for the development of AR applications using HoloLens. It has also become widely used in the field as recently it has become an open source for other glass types to use. For VR development there are different Software Development Kits (SDKs) available in the market. OpenVR is an SDK that enables programs to use different VR devices without needing to know the specifics of VR devices [

33]. Other popular VR SDKs are Oculus SDK, SteamVR SDK, Google VR SDK [

34]. Developers use VR platforms such as Steam VR, Oculus Home, and Windows Mixed Reality which offer comprehensive ecosystems to share VR content. Developers leverage these technologies to develop interactive, easy-to-share VR applications for manufacturing applications [

35].

3.2.5. Overview of Hardware and Software Used in AR/ VR Applications in Manufacturing

The review articles have been scrutinized to get the trend of software and hardware used in AR/VR applications is illustrated in

Table 5. The table offers a snapshot of various AR and VR applications, highlighting the diverse range of hardware and software technologies employed across different research groups.

Unity and Vuforia SDK are the most commonly used software platforms in the reviewed AR papers. Marker-based and feature-based tracking methods are mostly used, with Vuforia and ARToolkit frequently utilized for marker-based tracking. HoloLens appear as the most popular AR glasses.

For VR development, Unity is the predominant software platform for VR application development. Hardware-wise, HTC Vive and Oculus HMDs are prominently used in VR visualization. These headsets utilize advanced tracking technologies like SteamVR and Tobii eye-tracking.

Table 6.

Communication Technology used in AR/VR-based manufacturing using edge devices.

Table 6.

Communication Technology used in AR/VR-based manufacturing using edge devices.

| Research Group |

Application |

Communication Technology |

| [132] |

Machining operation |

Wireless TCP/IP |

| [37] |

Human-robot collaboration |

Modbus TCP |

| [105] |

Digital twin |

Wireless TCP/IP |

| [29] |

Human-robot collaboration |

ROSbridge (websocket) |

| [36] |

Machine operation |

TCP/IP Protocol |

| [63] |

Machine operation |

Websocket |

| [78] |

Maintenance application |

WebRTC protocol |

| [133] |

SCADA system |

Wireless TCP/IP |

| [70] |

Maintenance application |

Ultra-Wide Band (UWB) |

| [134] |

Human-robot collaboration |

ROSbridge (wifi) |

| [23] |

Quality assessment operation |

Wireless TCP/IP |

3.3. RQ3: What Are the Emerging Technologies in the Field of AR/VR Applications in Manufacturing?

This research question aims to identify and explore the emerging technologies that are used in AR/VR applications for manufacturing. By investigating these advancements, the objective is to identify the technological trends of current manufacturing practices through the integration of AR/VR technologies.

During the initial phase of AR/VR technology development, manufacturing applications were primarily image or video-based, lacking interactive capabilities and closed-loop mechanisms, thus providing limited feedback from user interactions. However, with substantial research in the AR/VR domain, advancements in key technologies have propelled these applications towards increased interactivity and closed-loop features, significantly enhancing the overall user experience and system responsiveness.

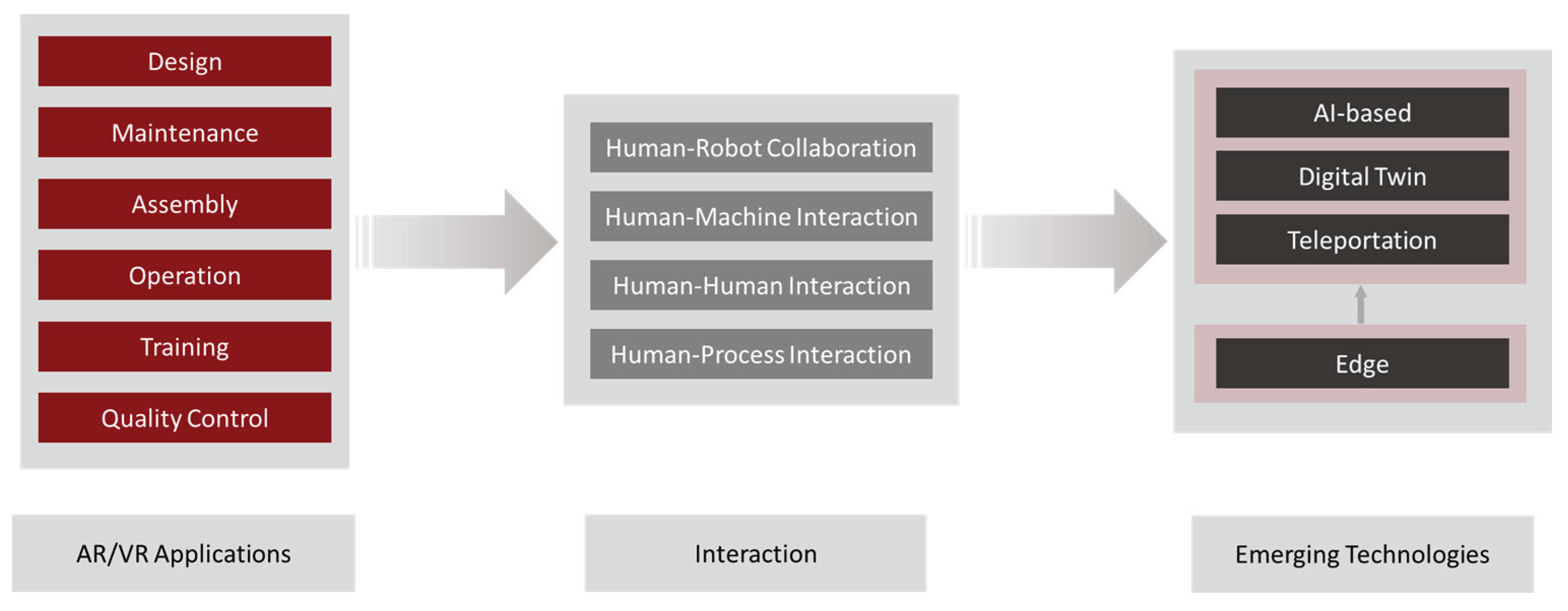

After a careful review of the articles, emerging technologies that are driving AR/VR technology towards technological maturity for implementing closed-loop manufacturing applications are identified. Artificial Intelligence (AI), Digital Twin, Teleportation, and Edge Technologies are among those emerging technologies that are listed in

Figure 11. Human interaction is a vital part of any closed-loop manufacturing system. Due to the advancement of industrial robotics, interaction with the system is becoming more and more challenging. For this reason, human-robot collaboration is becoming one of the emerging fields of research, and AR/VR becoming an integral part of applications involving human-robot collaboration. In the subsequent sections, the key findings of these technological trends and their applications in the AR/VR domain are discussed in detail while proposing generalized architectures for the implementation of these technologies in the aspect of manufacturing industries.

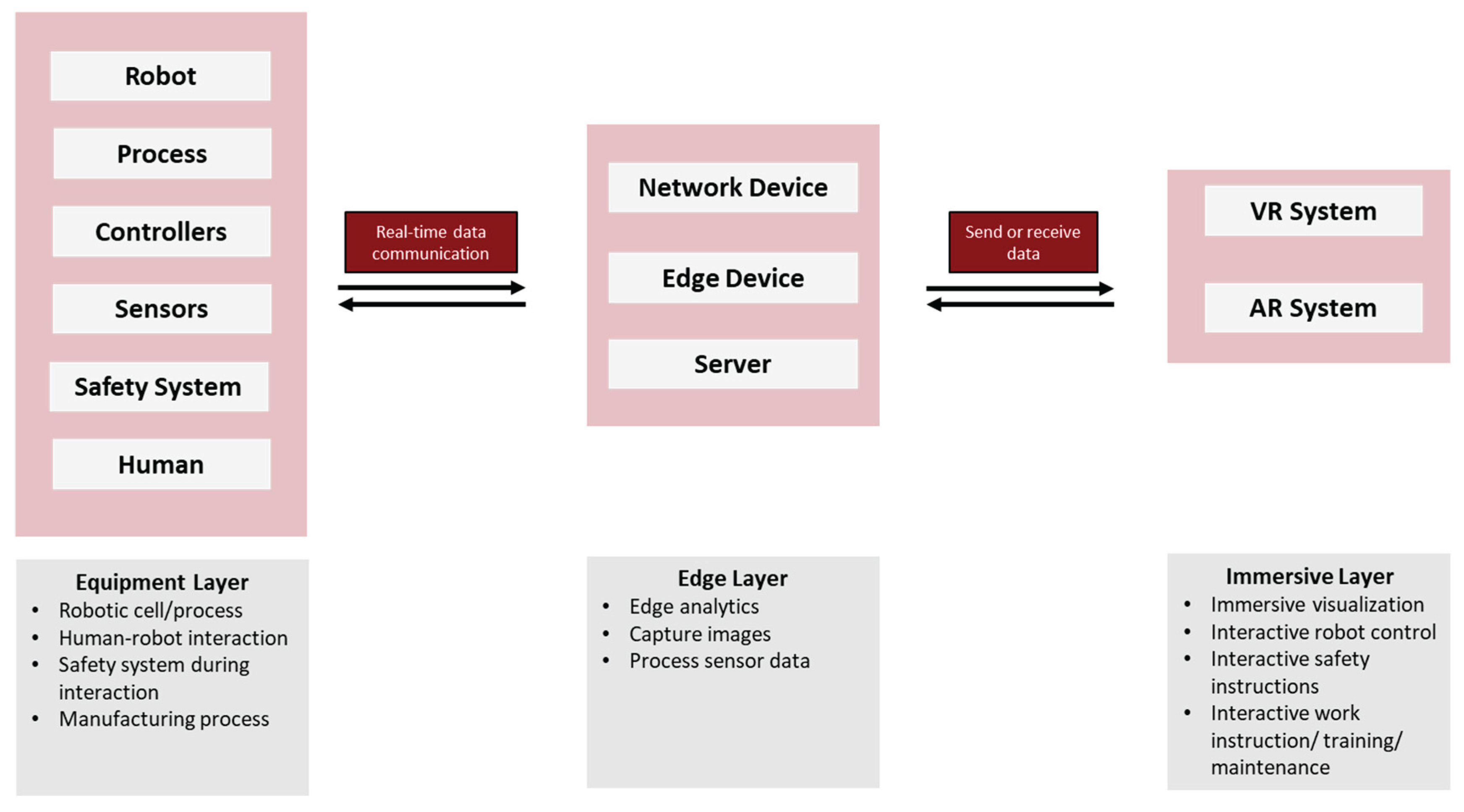

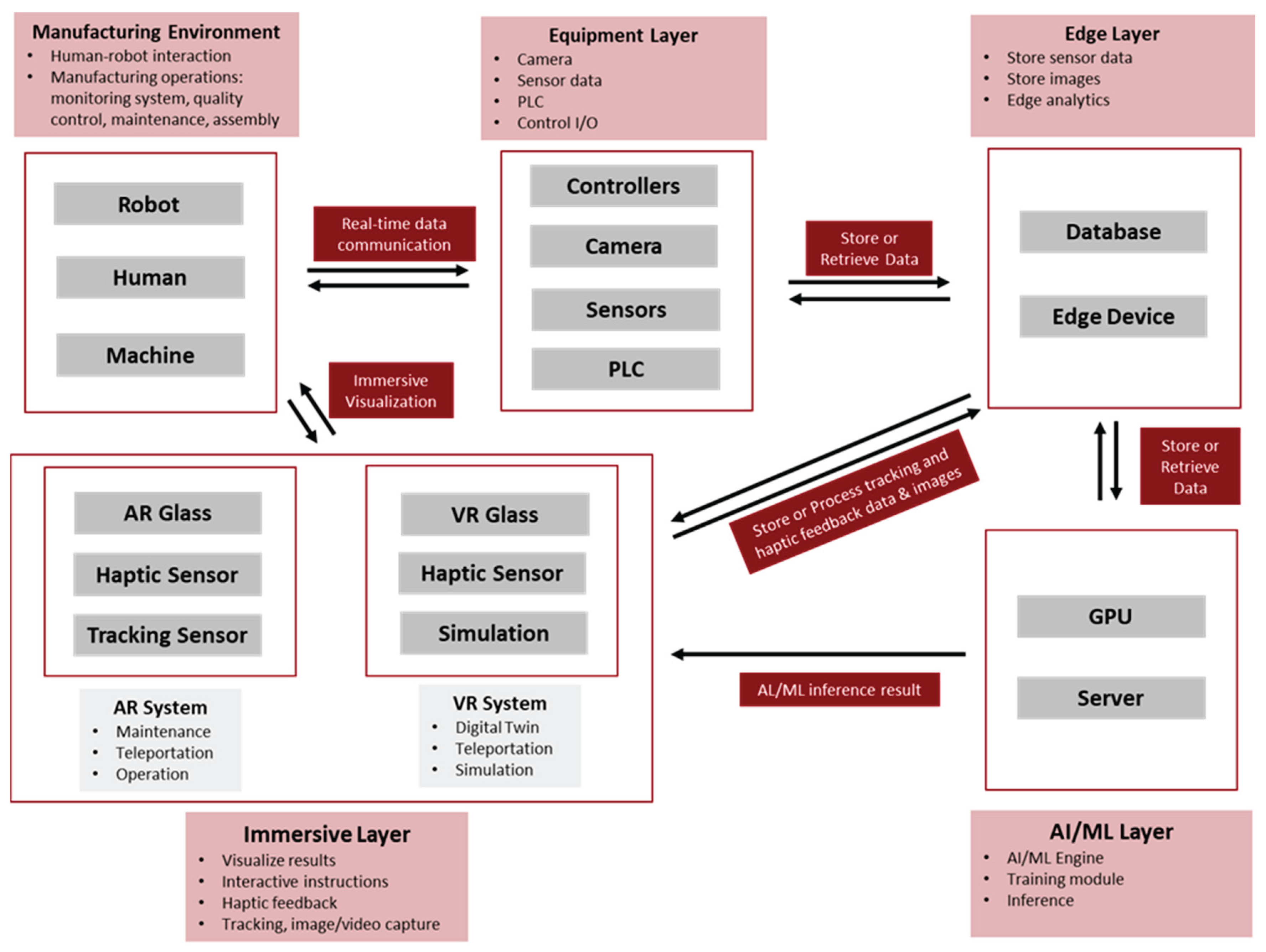

3.3.1. Edge Applications

AR/VR technologies play a vital role in manufacturing process monitoring, providing real-time and interactive process information, quality control, maintenance, and training applications. One of the key technologies that are making this possible is the Internet of Things (IoT) and in a broad sense, edge devices. AR/VR in conjunction with the Internet of Things (IoT), machine diagnostics are being overlayed onto the machine and production environment making manufacturing operations and troubleshooting more interactive and efficient. Leveraging edge devices, AR and VR have significantly enhanced the manufacturing processes by getting the data from the physical systems in real-time and creating a deeper and more immersive experience. Getting the physical systems data such as manufacturing data from PLC, robot controller’s data, wireless sensors, and wired sensors data which are local as well as distributed needs to be transferred from the equipment layer in real-time to the edge layer. The edge layer processes the data using edge devices and central processing servers to transfer it to the immersive visualization layer for AR/VR-based visualization and interaction. In one study, authors demonstrated an AR-based alert and early warning system for real-time machine health monitoring which was deployed on Android devices and Microsoft HoloLens, and data was collected from the physical system using TCP/IP protocol [

36]. The solution intends to notify the operators via notifications whenever an alarm arises on a machine and provide alarm information.

AR/VR with edge intelligence can also be used for monitoring the machining operation. The authors of [

37] proposed a VR system with a robot, replacing the traditional human-machine interface (HMI) console to visualize real-time robot trajectories for predicting errors and accident prevention and replay previously executed trajectories from a database for post-operation error analysis. Here the data has been transferred using the Modbus TCP protocol. Communication protocols are a vital part of implementing AR/VR-based manufacturing applications that use edge devices. Communication protocols vary based on the use cases and the hardware used for the applications.

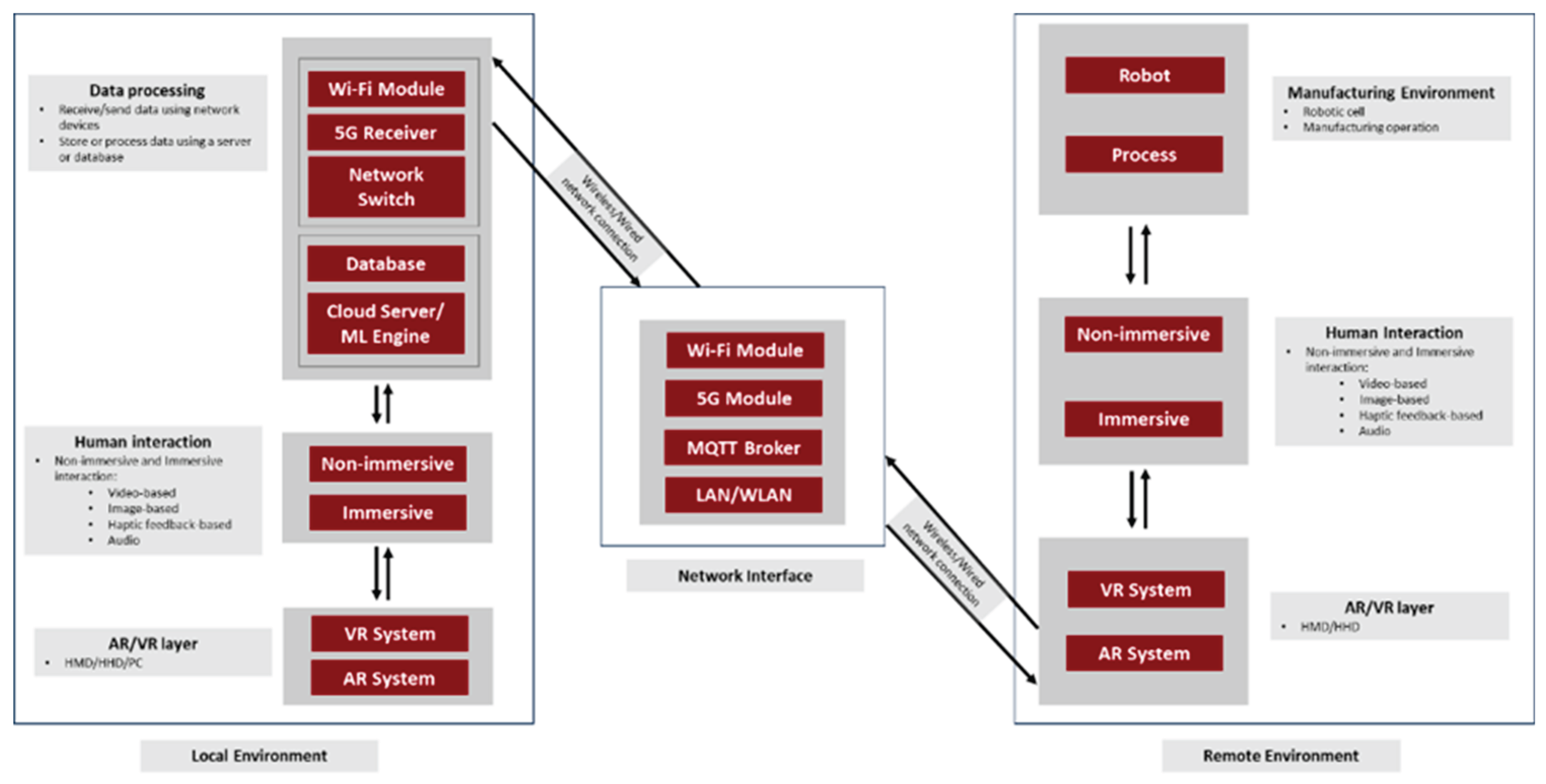

Error! Reference source not found. lists some communication technologies used in AR/VR-based applications using edge devices in manufacturing. The proposed generalized architecture for implementing AR/VR applications using edge devices is shown in

Figure 12. The architecture can be more complex based on the use case.

3.3.2. AI-Based Applications

AR/ Manufacturers are increasingly utilizing Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) techniques to enhance their processes with the goal of improving overall operational efficiency. One study conducted comprehensive research regarding the applications of classical machine learning and deep learning methods and the authors identified that there is a growing trend of implementing machine learning and AI algorithms in manufacturing operations [

38]. AI joined with AR/VR in manufacturing can unlock advanced capabilities and future innovations. AI-based applications are one of the most promising fields of future research in the AR/VR domain. AI is predominantly used in image processing and computer vision, making it a potential tool for AR/VR systems as image recognition, object detection, and pose estimation are crucial parts of AR/VR systems. An immersive system with AI features involves several key steps to integrate real and virtual environments seamlessly. These steps start with calibrating the virtual camera with the real camera to ensure an accurate depiction of the real world. Then, dynamic objects are detected, and tracked in real-time, and the real camera’s pose estimation is done. This information is used to create and render virtual objects that are aligned with the real environment, enhancing the user’s AR experience [

39]. Several research works have been performed to implement and improve AI-based AR/VR applications. The deep learning-based Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is widely used for identifying objects in images. One of the prominent methods in this area is the Region-based CNN (R-CNN) [

40,

41,

42]. The authors of [

43] used multimodal AR instructions in conjunction with a tool detector built with a Faster R-CNN model trained on a synthetic tool dataset to increase worker performance during spindle motor assembly testing of a CNC carving machine. The system reduces assembly completion time and mistakes by 33.2% and 32.4% respectively compared to the manual assembly process. Many researchers also used YOLOv5, a state-of-the-art object detection model, for real-time and accurate object detection in AR/VR applications [

44]. Pose estimation of industrial robots is vital in AR/VR manufacturing applications as it enables the precise alignment of virtual objects with real-world objects or locations and AI can play a vital role in implementing almost real-time post-estimation. In one study, authors proposed a markerless pose estimation method using CNN to reference AR devices and robot coordinate systems [

45]. The architecture of the proposed system used both RGB-based and depth-image-based approaches which offer automatic spatial calibration.

Generative AI, one of the newest fields in AI, has the transformative potential in AR/VR applications in manufacturing by enhancing situational awareness and enabling more efficient maintenance and design processes [

46,

47]. By integrating large language models with augmented and virtual reality, manufacturers can provide real-time, context-aware assistance to workers, enabling hands-free operation and in situ knowledge access [

48]. These technologies can support tele-maintenance and consultation, allowing experts to guide on-site technicians remotely with immersive, interactive experiences [

49]. Furthermore, VR-enabled chatbots facilitate the customization of complex products by offering intelligent, natural language interactions that streamline the design and manufacturing processes [

50].

Table 7 lists some AR/VR-assisted AI-based manufacturing applications. Selection of the algorithm, quality of data, computational speed and data transfer speed are the key aspects of AI-based manufacturing applications using AR/VR. The proposed generalized system architecture for implementing AI-based AR/VR-assisted manufacturing applications is shown in

Figure 13.

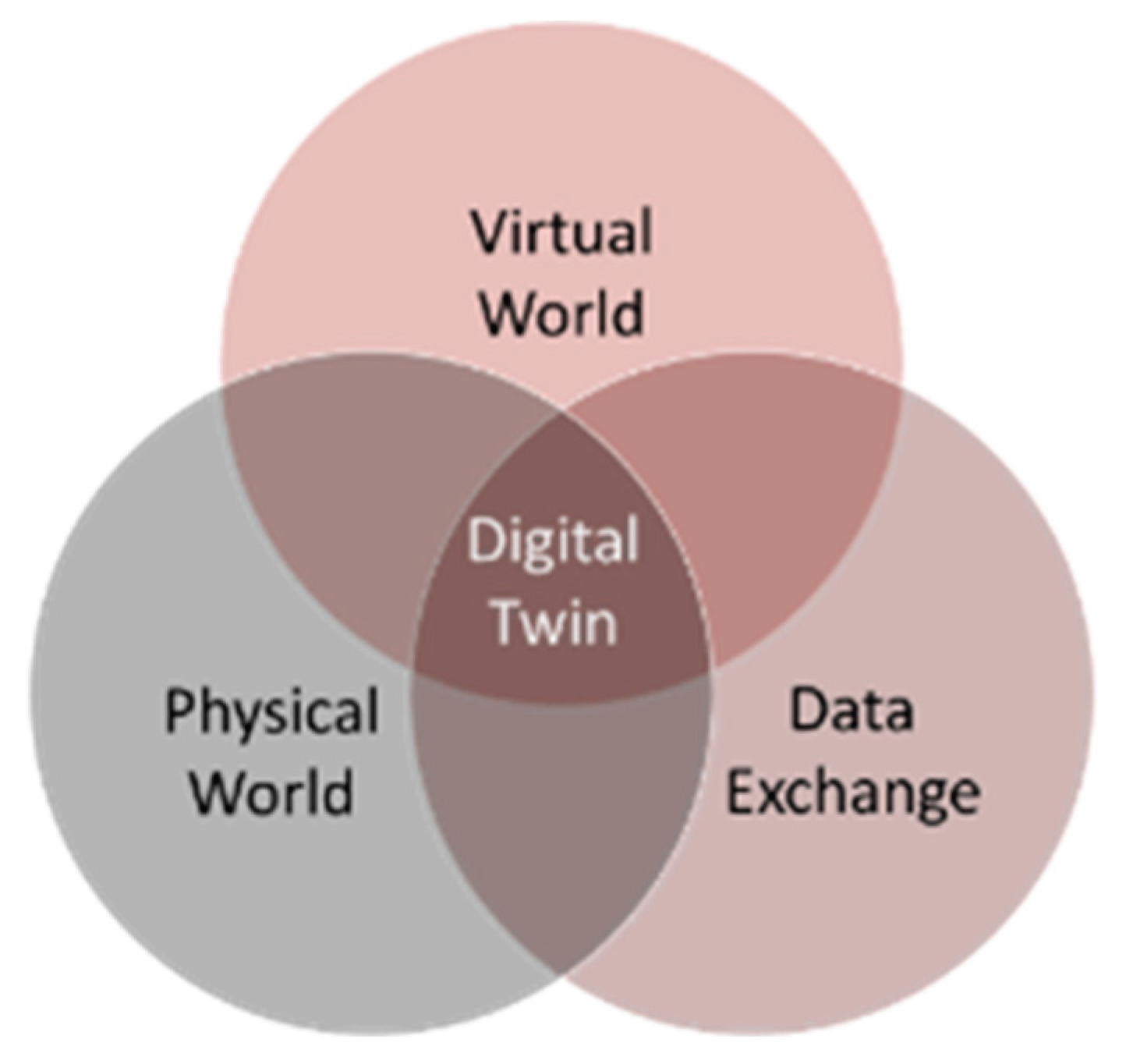

3.3.3. Digital Twin Applications

Digital twin applications using AR and VR are one of the transformative tools in manufacturing for digital transformation providing smart decision support [

51]. Different authors represented the definition of the term ‘digital twin’ in different ways. Authors of [

51] provided a generalized and consolidated definition of ‘digital twin’ which is the most suitable definition for this literature review:

“digital twin is a virtual representation of a physical system (and its associated environment and processes) that is updated through the exchange of information between the physical and virtual systems.” The main features of a digital twin application are illustrated in

Figure 14 [

51]. AR and VR are the key technologies to implement digital twin-based applications in manufacturing such as product design and development, simulation, training, machine and robot calibration, and fault diagnosis. Research has been performed to implement digital twin-based AR/VR-based applications in manufacturing. Authors of [

52] proposed an AR-assisted robot robotic welding paths programming system. The authors overlaid the virtual robot on the actual robot and a handheld pointer was tracked using an Optitrack Flex 3 camera motion capture system to directly interact with the workspace and to guide the virtual robot’s movements and path definitions.

Table 8.

Digital twin application in manufacturing using AR/VR.

Table 8.

Digital twin application in manufacturing using AR/VR.

| Research Group |

Application |

Type of Visualization |

| [52] |

Robot welding programming |

Immersive |

| [37] |

Simulation and training |

Immersive |

| [53] |

Human-robot collaboration |

Immersive |

| [182] |

Robot programming |

Immersive |

| [54] |

Human-robot collaboration |

Immersive |

| [113] |

Remote human-robot collaboration |

Immersive |

| [116] |

Process monitoring |

Non-immersive |

| [103] |

Design review application |

Immersive |

| [183] |

Robot programming |

Immersive |

| [135] |

Assembly operation |

Immersive |

| [61] |

Human-robot collaboration |

Immersive |

| [60] |

Remote human-robot collaboration |

Immersive |

| [138] |

human-robot collaboration |

Immersive |

| [181] |

Robot programming |

Immersive |

| [112] |

CNC milling machine operation |

Immersive |

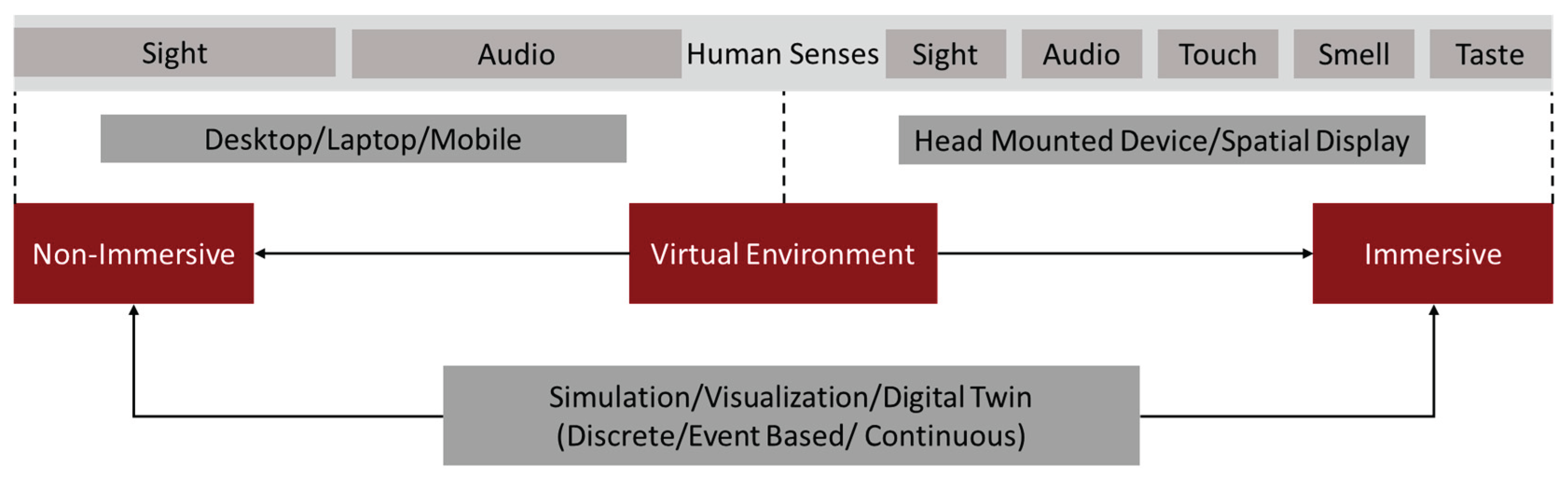

Traditional HMIs sometimes have limited capabilities in interacting with the physical world. By using digital twin features, AR/VR systems are becoming a preferred choice for replacing traditional HMIs. Considerations need to be made while choosing the level of virtualization for digital twin applications. Digital twin-based AR/VR systems can be immersive and non-immersive. Conventional non-immersive virtual systems engage sight and hearing through visualization of the computer screen while keeping users connected to the physical world. On the other side, immersive virtual systems isolate users from reality and facilitate interaction within the virtual environment using specialized haptic devices. There are different levels of virtualization in virtual systems shown in

Figure 15 [

53]. In one study, authors developed a VR system with a robot to replace the traditional HMI console to visualize real-time robot trajectories for predicting errors and preventing accidents. The system can replay previously executed trajectories from a database for post-operation error analysis [

37].

VR systems were seen to be used more often in the sense of DT applications. They were mostly used off site where AR would be less useful. When being used for AR, they were used as a way of creating content for the application, less immersive. DTs were often used for training scenarios in a more immersive format. This gave trainees the option to simulate being on a shop floor without the dangers of being inexperienced with equipment.

In another study, a virtual robot model was overlaid on a physical robot system and users can interact with the system using Microsoft HoloLens. The Virtual layer converts the user-defined trajectories into robot commands and the Robot Operating System (ROS) layer processes these commands to communicate with the industrial robot controller [

49].

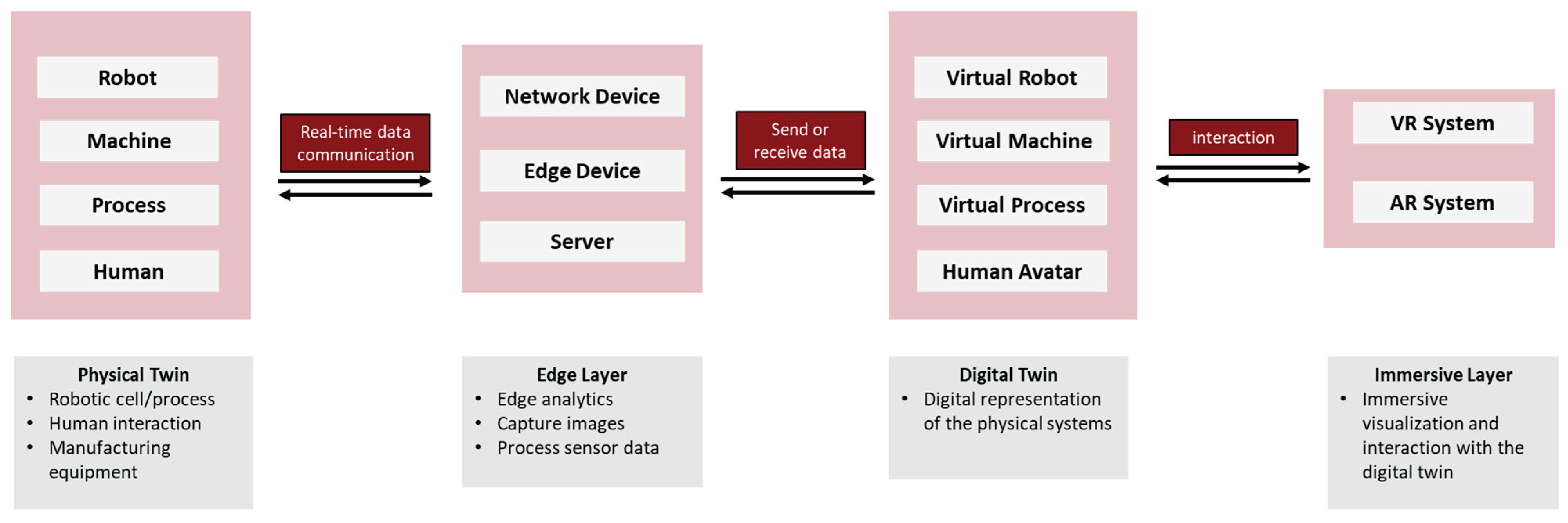

Digital twin features can be used for remote operations also. The authors used HTC Vive headsets and the Unity plugin PUN2 to synchronize users and handle the network for multiuser communication. identifies some general manufacturing applications of AR/VR using digital twin technology. The proposed generalized system architecture for implementing digital twin-based AR/VR-assisted manufacturing applications is shown in

Figure 16.

3.3.4. Teleportation and Remote Collaboration Applications

Remote collaboration enables the experts to share their knowledge and guide engineers, operators, and technicians with less domain knowledge to troubleshoot manufacturing operations. In addition, remote collaboration enables designers and product developers to collaborate from different locations which can significantly reduce the product or process development time. Traditionally remote collaboration is done using video and audio-based communication [

55]. However, it has limited interaction capabilities. With the recent advancement of immersive technologies (AR and VR), remote collaboration and teleportation applications are becoming more interactive and realistic by providing haptic feedback and sensing capabilities. A growing amount of research has been done in the field of AR/VR-based teleportation and remote collaboration. The authors of [

56] demonstrated the process of improving the effectiveness of teleoperated robotic arms for manipulation and grasping activities using Augmented Visual Cues (AVCs). A case study with 36 participants was conducted to validate the system’s usefulness, and the authors also employed NASA Raw-TLX (RTLX) to quantify task performance [

57]. In another study, authors proposed a situation-dependent remote Augmented Reality (AR) collaboration system that offers two functionalities: image-based AR collaboration for limited network or device capabilities and live video-based AR collaboration with a synchronized VR system. For image-based collaboration, annotations are added directly onto 2D images, or a 3D perspective map is generated and for the synchronized VR mode annotations are attached to a virtual object to eliminate inconsistencies while changing the viewpoints during collaboration [

58]. In remote collaboration, the remote users need to have dimensional knowledge about the location they are interacting with. Often the virtual environment of the physical system is developed to get knowledge about the physical system remotely. The development of the virtual system is challenging, and serval research studies have been done on developing virtual systems for teleportation and remote collaboration. Authors of [

59] introduced a methodology for creating a point cloud-based virtual environment incorporating regional haptic constraints and dynamic guidance constraints for teleportation operation. The system integrates a virtual robot model with real-time point cloud data and haptic feedback, allowing operators to control the virtual robot using a haptic device. The authors of [

55] proposed an AR-based multi-robot communication system using digital twins (DT) and reinforcement learning (RL) algorithm for teleportation operations. The digital twin of the industrial robots is mapped onto the physical robots and visualized using AR glasses and the RL algorithm is used for robot motion planning which replaces the traditional kinematics-based movement with target positions.

Table 9 identifies some general manufacturing applications of AR/VR for teleportation and remote collaboration. The proposed generalized system architecture for implementing AR/VR-based teleportation applications in manufacturing is shown in

Figure 17.

Teleportation applications were also more often found to be used in VR applications over AR. Due to the format being more immersive, allowing for the user to simulate being near equipment. This however does not mean that AR cannot be used for teleportation applications.

3.3.5. Human-Robot Collaboration Applications

In the development of any manufacturing application, human interaction is an integral component. While robotics and automation have significantly advanced manufacturing processes, human interaction remains an essential part of the successful operation of manufacturing operations. For this reason, human-robot collaboration has become a prominent field of research. AR and VR are among the leading technologies that have been used to make human-robot collaboration more interactive. In one study, authors proposed a multi-robot collaborative manufacturing system with AR assistance where humans use AR glasses to determine the position of the physical robot’s end-effector, and an RL-based motion planning algorithm calculates the joint value solution that is viable [

60]. In another study, the authors proposed an HRC collaboration system using VR for human-robot simulation. The authors used Tecnomatix Process Simulate (TPS), Universal Robots, and an HTC Vive VR headset to perform an event-driven human-robot collaboration simulation [

53].

The authors of [

54] proposed an AR-based human-robot collaboration system with a closed compensation mechanism. The proposed system used four layers: the AR Layer, the Virtual Environment, the Robot Operating System (ROS), and the KUKA Robot Controller layer. Microsoft HoloLens was used to interact with users, allowing them to control a virtual robot model overlaid on an actual robot using gestures, and user-defined trajectories were converted into robot commands.

Authors of [

61] leveraged a Mixed Reality (MR) system, deep learning, and digital twin technology to develop a Human-Robot Collaboration (HRC) system by calculating real-time minimum safety distances. The system also provides task assistance to users using Microsoft HoloLens 2.

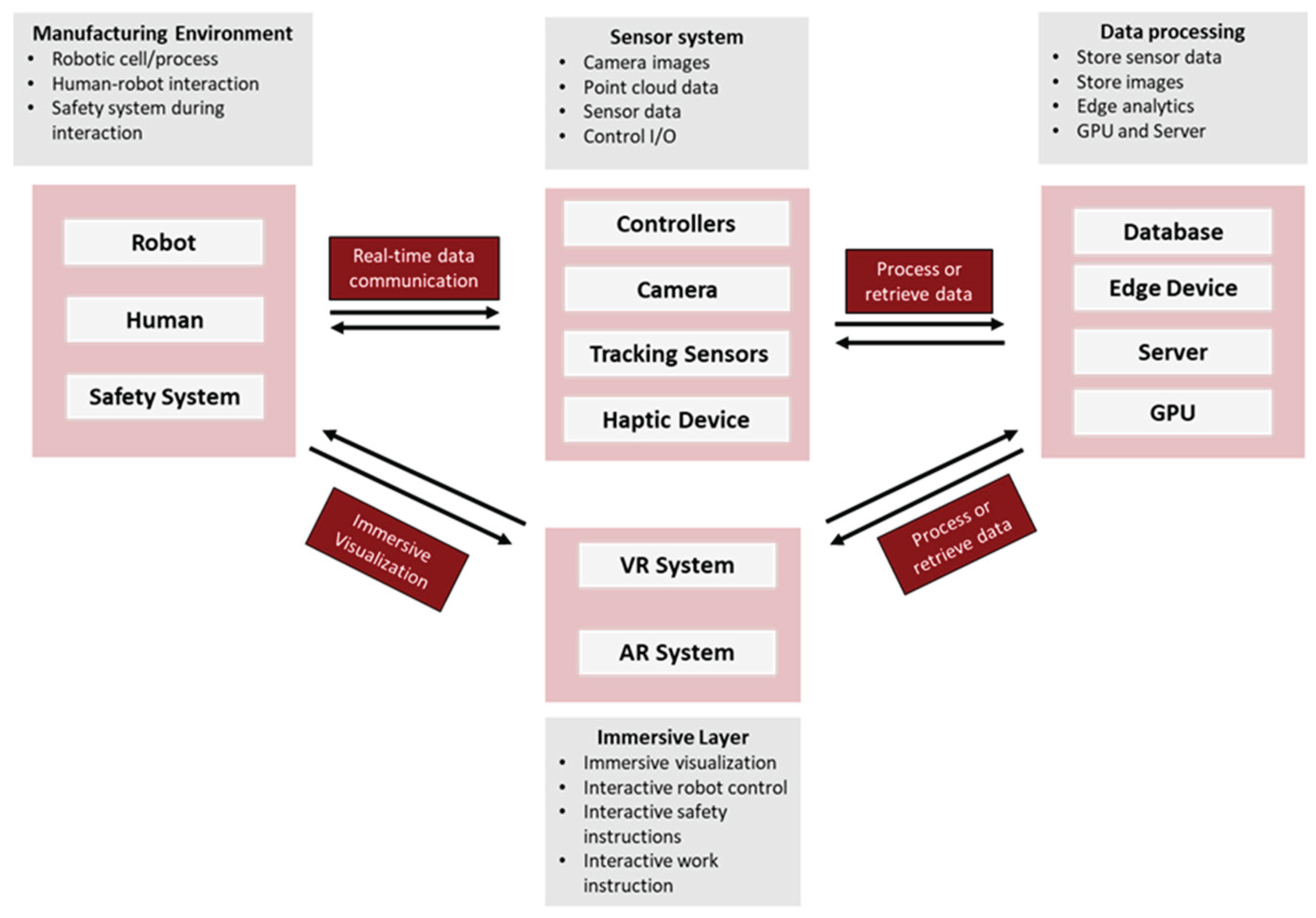

Table 10 identifies some general manufacturing applications of AR/VR for human-robot collaboration. The proposed generalized system architecture for implementing human-robot collaboration using AR/VR is shown in

Figure 18.

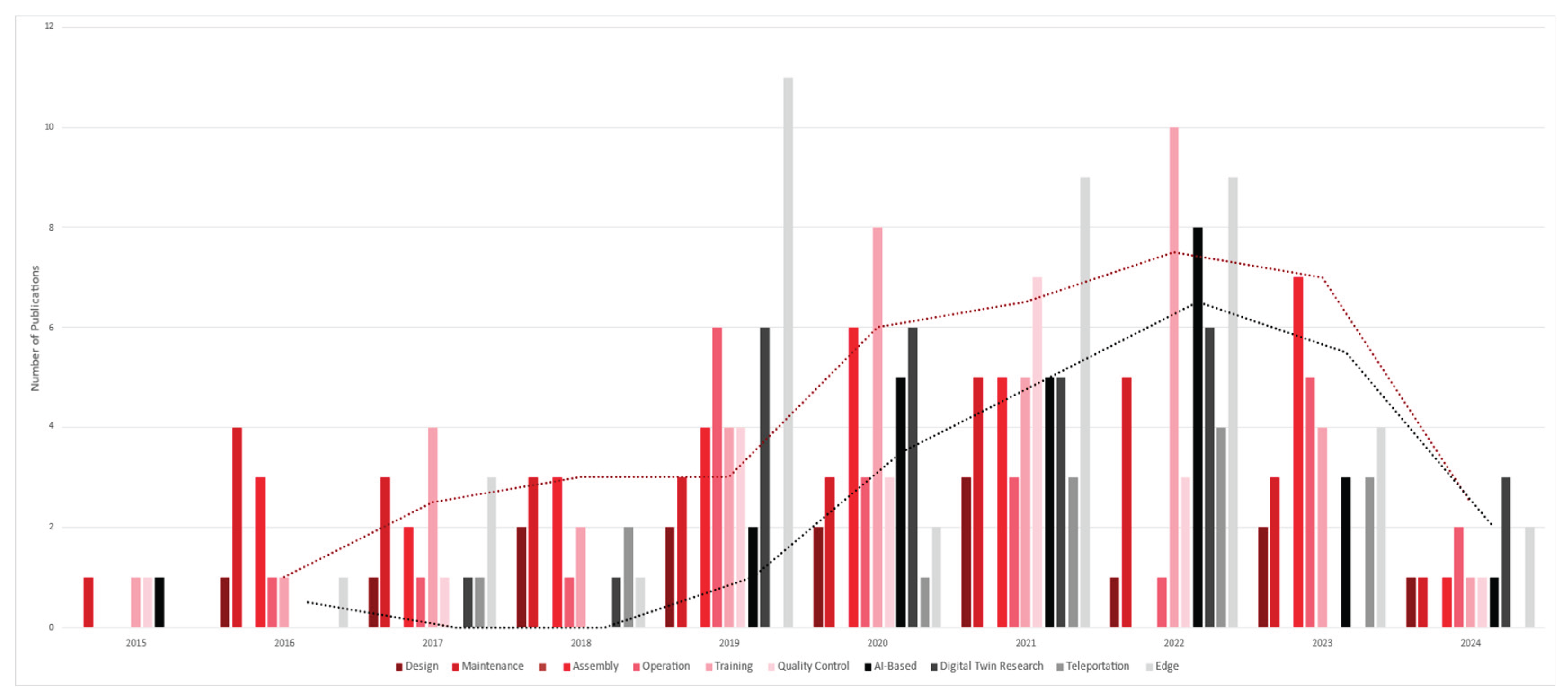

The statistical analysis of research papers focusing on applications and emerging technologies is illustrated in

Figure 19. The red scale within the figure represents applications, while the grey scale denotes the different technologies utilized. The findings reveal a notable surge in interest towards AR/VR applications for manufacturing across various domains in recent years.

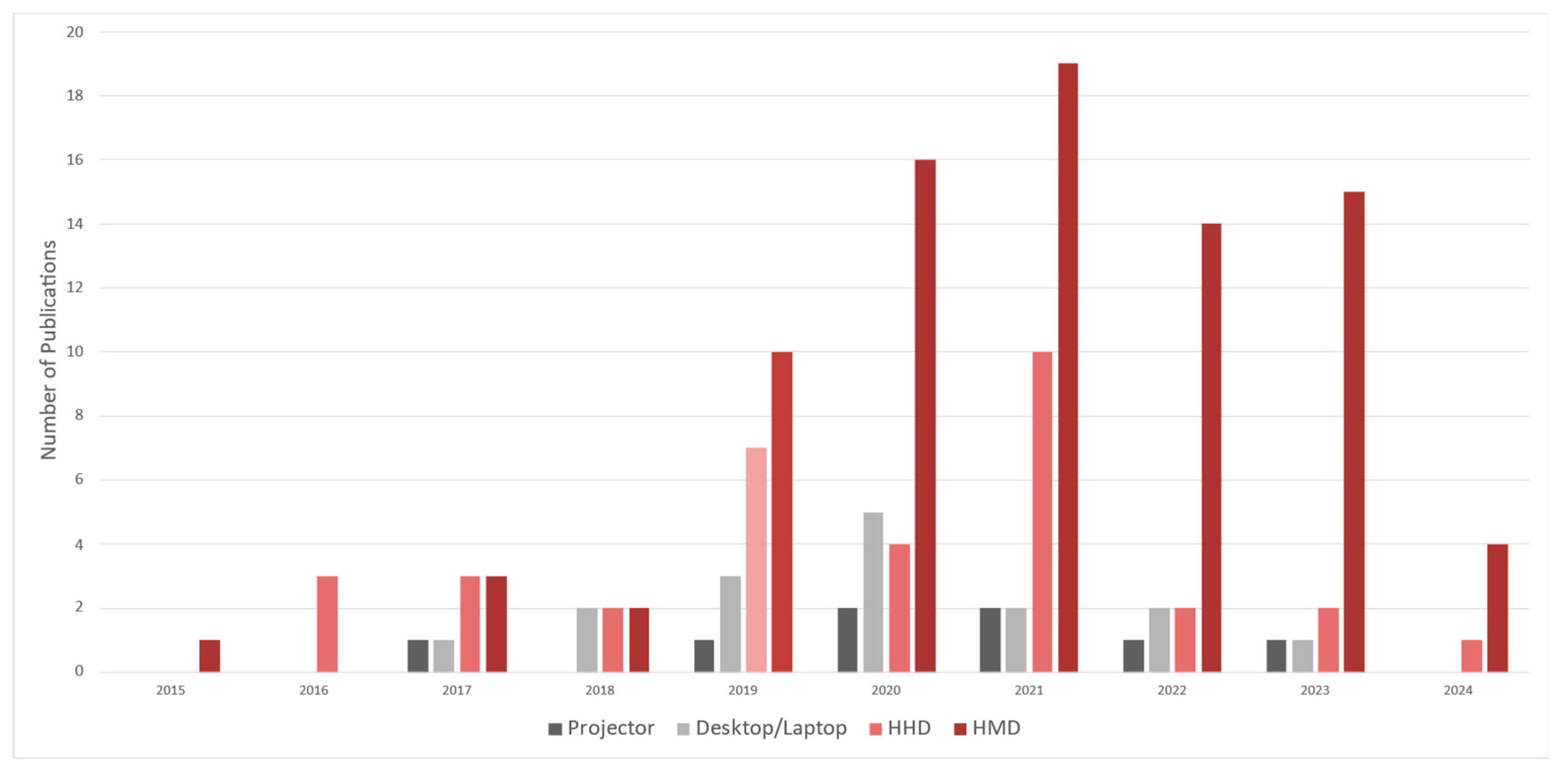

Figure 20 presents detailed statistics on the utilization of AR/VR devices within the reviewed papers. It is observed that Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) emerge as the preferred choice for immersive visualization among these devices. This preference may be attributed to the development of new Software Development Kits (SDKs), resulting in more accessible and stable application development compared to previous years. Additionally, the rise of emerging hardware has facilitated the creation of more affordable and user-friendly AR/VR applications.

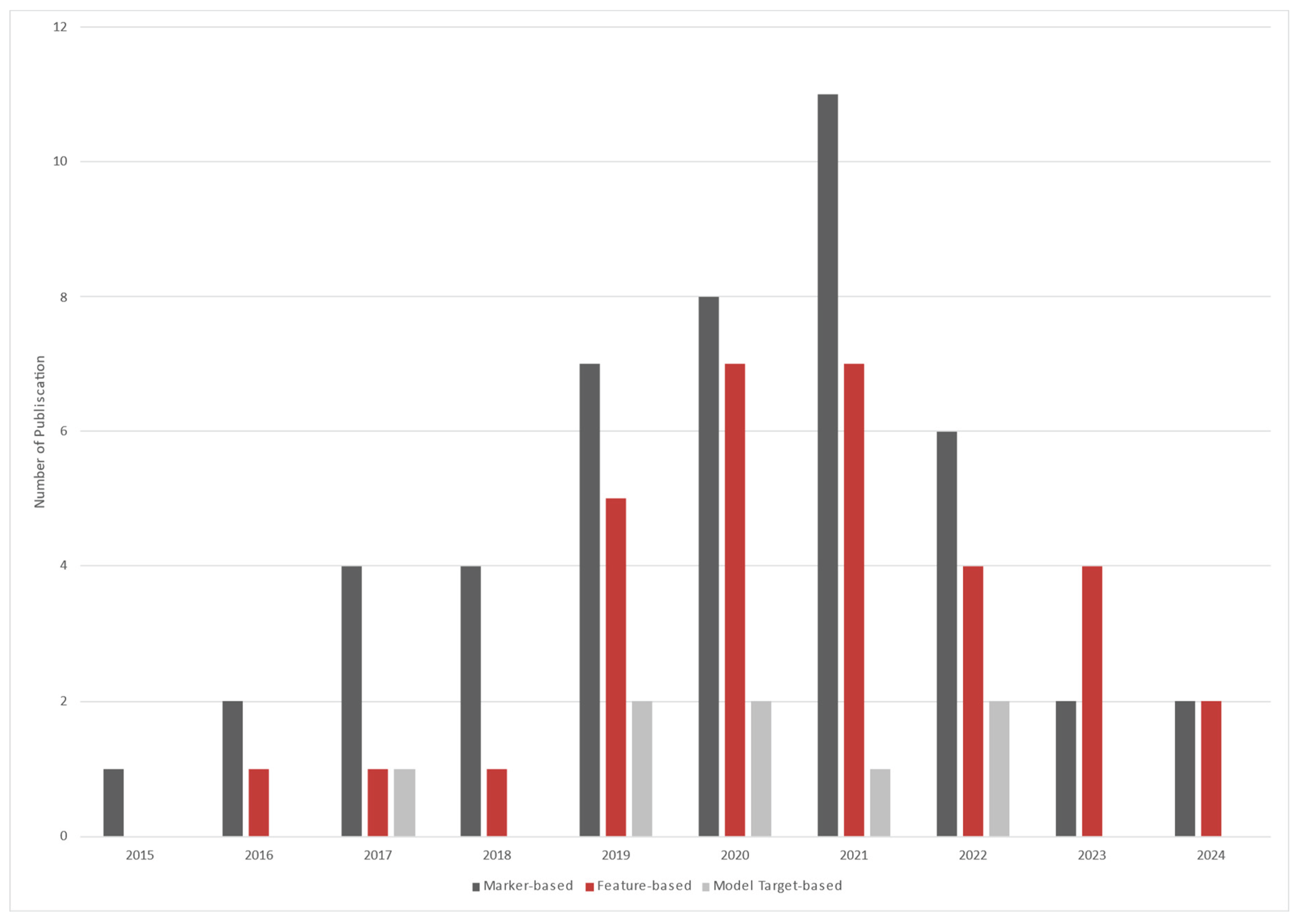

Furthermore,

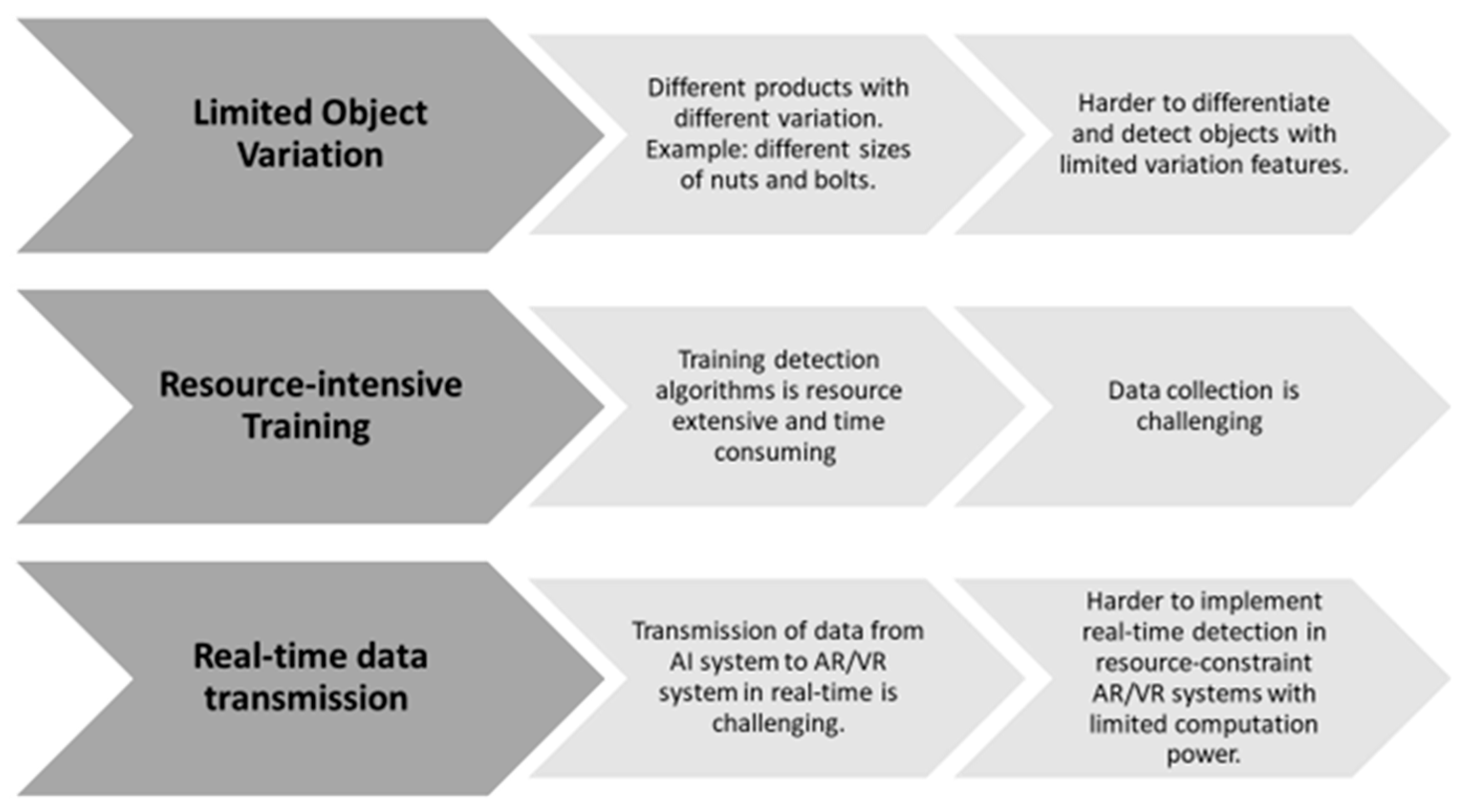

Figure 21 illustrates the statistics on tracking technologies employed in AR/VR applications. Mark-based tracking technologies remain popular due to their ease of implementation. However, there has been a growing trend towards feature-based tracking over the years, driven by its ability to track immersive content without the need for physical markers. However, the 2023 to 2024 papers show little to no use of model-based tracking. This could be due to the newer ease of creating feature-based tracking models. More and more introductory technologies come with features of making these models without the need of external sources. Many smart phones come with lidar sensors built in. Most of the papers that use HHDs as their viewing device often use markered tracking methods. These are often preliminary applications and prevent the need for investing into expensive hardware.

3.4. RQ4: What Are the Challenges for the Adaptation of AR/VR Applications in Manufacturing?

There are many challenges in applying AR/VR applications in manufacturing environments. These challenges are categorized as technological challenges, organizational challenges, and environmental challenges.

3.4.1. Technological Challenges

In this section, different technological challenges of AR/VR technologies in manufacturing applications are discussed in detail.

Tracking and registration are the most vital of any AR/VR application. Real-time tracking is preferred for AR/VR-based manufacturing applications. Different tracking technologies are discussed in

Section 3.2.2. Among those tracking technologies, marker-based tracking is the most widely used and easier choice for AR/VR-based manufacturing applications and for this reason, many researchers used marker-based tracking for manufacturing applications [

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]. Marker-based tracking systems face challenges from maker occlusion making a part or entire marker not viewable using the tracking system [

67]. As the manufacturing system is complex in nature marker occlusion can easily happen to any movable parts which need to be tracked. The alternate approach to solve this problem is the markerless tracking system. Simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) is commonly used in markerless tracking [

26]. In one study, authors developed a quick development toolkit using SLAM and QR code for augmented reality visualization of a factory [

68]. AI-based deep learning techniques can also be used for markerless tracking. However, there are many challenges in applying these technologies with immersive technologies for markerless tracking in the manufacturing environment. In the manufacturing environment, there are products with limited variations such as nuts and bolts of different sizes but with the same shapes. These products are harder to differentiate, making it challenging for object detection algorithms to detect the desired objects. Again, training these algorithms is sometimes resource-intensive and time-consuming which makes it harder to implement it in AR/VR systems [

39]. Additionally, collecting data from the manufacturing process is challenging and there is also data privacy issue in manufacturing industries. Another challenging part of implementing these algorithms in AR/VR systems is real-time data transmission. Modular AR/VR devices are resource-constraint devices and have less computation power and in most cases cannot run AI algorithms. In this scenario, object detection algorithms need to run on the remote server and decisions have to be transferred to the AR/VR systems using network devices in real-time which is very difficult to implement [

39]. The challenges of implementing markerless tracking with AR/VR systems in manufacturing are listed in

Figure 22. Registration of the virtual component in the immersive environment depends on the successful tracking of the object [

67]. The accuracy of the tracking and the correct alignment of virtual components in the real environment are challenging to implement in complex manufacturing settings.

There are many AR/VR devices available for implementing AR/VR applications but selecting the proper AR/VR device for a specific manufacturing application can be challenging. Selection of the AR/VR devices depend on various types of factors such as the price, battery life, desired field of view, optics technology, camera type, open API support, audio technology, sensor technologies used, haptic controls, processor, memory and storage, data connectivity options, operating system, ingress protection (IP rating) and appearance among other factors. There is no standardized benchmarking tool for the evaluation of AR/VR devices for manufacturing applications [

69]. In one study, the authors developed a VR benchmark for assembly assessment but generalizing the benchmark for any manufacturing environment is complex [

70].

The advancement of AR/VR in the industrial sector faces a multitude of challenges that hinder its progression. Primarily, the absence of universally applicable methods for designing applications is a notable impediment. AR development typically operates on a bespoke, case-by-case basis, tailored to the unique requirements of individual systems. This approach can prove to be cost-prohibitive, particularly when considering the need to design and implement distinct applications for various sectors within a manufacturing plant [

10]. The absence of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution also extends to the compatibility of AR/VR software with different hardware platforms. When developing an application, the intricacies of setup procedures are intricately tied to the specific software and hardware combination for which the application is intended. For instance, an application designed for the HoloLens platform cannot be seamlessly transferred to another Head-Mounted Display (HMD) device [

2]. These developmental challenges are further exacerbated by the demand for job-specific solutions. Diverse job roles necessitate distinct hardware and software requirements, influenced by factors such as environmental conditions, machinery configurations, and the availability of specific models. Achieving a harmonious approach to application development across different areas within a singular environment remains a formidable task. Currently, the industry lacks convenient ‘drag-and-drop’ solutions, which could potentially reduce employment costs and standardize application development practices.

The cybersecurity threat is among the top concerns for implementing AR/VR-based manufacturing applications. Confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA), data theft, observation attacks for graphical PIN in 2D, security, privacy, and safety (SPS), granular authentication and authorization, and latency problems are the most frequent cyber security concerns in AR/VR systems [

71]. Therefore, careful development needs to be done for AR/VR-based manufacturing. If the system gets exposed attackers can easily get secret information that might jeopardize any manufacturing company with substantial financial loss.

3.4.2. Organizational Challenges

In the field of manufacturing, Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) are very new technologies that have huge transformative potential. Given the novelty of the technologies, acceptance and adoption by end-users are imperative for the successful integration of these technologies. Consequently, many scholarly research articles focused on understanding the user acceptance and the usability of AR/VR applications within the context of manufacturing contexts. Various researchers have adopted different systematic approaches to adopt AR/VR systems tailored to manufacturing environments and emphasized the critical need for professional and strategic implementation of these technologies. Authors of [

21,

72], identified an architecture framework for the systematic development of AR applications. This framework can also be adopted for developing VR applications. The framework consists of five stages: concept and theory stage, implementation stage, evaluation stage, industry adaptation stage, and intelligent application solution stage [

21,

72]. In each phase of the architecture framework, careful considerations need to be taken and user evaluation needs to be done so that the applications can be well accepted in the manufacturing setting, and these are very challenging tasks. For this reason, AR and VR technologies are facing challenges to get adopted in the manufacturing industries.

Many of the papers found conducted field studies to examine how their application improved different metrics and how the users reacted to use. These studies ranged from 5 to 50 users at a time. While these some studies were conducted in large groups, they did not last for an extent of time that could give significant findings. Large scale field research with long usage periods must be studied to find how they would do in industry. This could improve how they are adopted not only by users but by companies as well.

AR/VR can prove to bring large returns on investment, especially with large overturn rates involved. However, this is dependent on accuracy, ease of use, and speed at which the application can be developed. The accuracy and ease of use of the applications can have an overall effect on the knowledge retention of the user. This cannot be evaluated at a higher level as there have not been studies with large enough field groups to determine if the applications are effective. Currently, most studies are done based on time to conduct tasks. While this is a good metric, there is more that can be done when determining the effectiveness of AR/VR. At the moment, there is also a lack of common knowledge on the use of AR/VR as it is an emerging technology in the public. This does not mean that people don’t know what it is, but there is a lack of knowledge of common practices or maneuvers when using applications, which causes a learning curve when implementing one of these systems.

3.4.3. Environmental Challenges

The environment has many different factors that can prove to be difficult for AR/VR systems to handle. This can include factors such as lighting, atmosphere, moving bodies, etc. Of these, occlusion seems to be one that gets a lot of attention. Occlusion can involve having to exclude objects in the field of view of the user like other people, the users’ hands, and other structures in the environment. As the AR system is the last layer of vision for the user, without occlusion handling, the virtual aspects can be displayed on top of objects that it shouldn’t. This can disrupt the flow of the application and the user experience [

73]. Occlusion systems also cause larger processing strains on the system which reduces the realism of the simulation and in some cases causes discomfort to the user. There have been many proposed solutions that involve the occlusion of specific types of objects in the field of view but have yet to have an all-inclusive solution [

26]. The use of CAD-based tracking has also been seen to improve partial occlusions and rapid motion, but this relies on the availability of CAD models [

10].

The identified emerging technologies and problems being faced with AR and VR discussed can be seen to correlate directly with each other. While many of the technologies are being researched individually, they should be looked at alongside each other. This would allow for different scenarios to be looked at with multiple problems being faced. For example, many of the papers choose a single tracking type when developing the application when this might not be the most optimal solution. Evaluating different challenges while being developed and tested during reporting would allow for newer papers to supersede these problems. The challenges being faced by AR and VR are often discussed apart from each other. This paper proves to show that they often face the same problems. When conducting literature reviews in the future, researchers can look into both realms to find challenges and solutions.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, a detailed examination of the applications of Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) within the context of the manufacturing industry was conducted. Both software and hardware components utilized in these applications were meticulously categorized and identified.

Research Question 1 (RQ1) systemically identified the current key applications of AR/VR in manufacturing by reviewing and analyzing various studies and examples. AR/VR applications enhance manufacturing processes, including maintenance, assembly, operations, training, product design, and quality control. The potential of AR/VR technologies extends beyond the identified core areas which includes inventory management, supply chain optimization, and customer engagement. These extended applications are not extensively covered in the reviewed literature which will be explored in future research.

Research Question 2 (RQ2) identifies the state-of-the-art technologies in AR/VR applications for manufacturing, offering a comprehensive overview of key components, hardware, and software utilized in this domain. Cutting-edge technologies were examined which include tracking systems, display devices, game engines, AR libraries, and VR development kits.

Research Question 3 (RQ3) highlights emerging technologies in AR/VR applications for manufacturing, providing a detailed exploration of cutting-edge advancements such as Edge applications, AI-based applications, Digital Twin applications, Teleportation, Remote Collaboration applications, and Human-Robot Collaboration applications. By synthesizing insights from various studies, the review identifies key technological trends of AR/VR technologies in modern manufacturing practices. However, challenges exist in implementing these technologies. There is a lack of standardized architectures for their implementation, and challenges related to interoperability and scalability persist. More industry-specific case studies and applications are needed for the large-scale adoption of these technologies.

Research Question 4 (RQ4) identifies challenges across technological, organizational, and environmental domains for the implementation of AR/VR-based applications in manufacturing. The section highlights the key technological hurdles like tracking and registration complexities, device selection and evaluation, development challenges, and cybersecurity threats that impact AR/VR implementation in manufacturing. Additionally, it highlights organizational obstacles such as user acceptance and return on investment, underscoring the importance of strategic frameworks for technology adoption. Research gaps remain in standardizing architectures and benchmarking tools for AR/VR devices in manufacturing, as well as in developing industry-specific case studies to facilitate broader technology adoption. Further research is needed to address environmental challenges like occlusion handling and other factors influencing AR/VR usability in manufacturing settings.

In conclusion, this paper provides a comprehensive overview of the applications, technologies, and challenges associated with implementing AR/VR in the manufacturing sector. Key findings highlight the diverse range of applications within manufacturing, from enhancing operations to exploring emerging technologies. Despite technological advancements, challenges such as tracking complexities and user acceptance barriers underscore the need for further research and standardized frameworks to maximize the potential of AR/VR in manufacturing.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded in part by NSF Award 2119654 “RII Track 2 FEC: Enabling Factory to Factory (F2F) Networking for Future Manufacturing,” and “Enabling Factory to Factory (F2F) Networking for Future Manufacturing across South Carolina,” funded by South Carolina Research Authority. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Disclosure of A.I Usage

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used “ChatGPT” to improve the readability, grammar correction, and language of the paper. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- V. R. Relji’c, I. M. Milenkovi’c, S. Dudi’cdudi’c, J. Šulc, and B. Bajči, “Augmented Reality Applications in Industry 4.0 Environment,” Applied Sciences 2021, Vol. 11, Page 5592, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 5592, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Egger and T. Masood, “Augmented reality in support of intelligent manufacturing – A systematic literature review,” Comput Ind Eng, vol. 140, p. 106195, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Y. Lu, M. Shpitalni, and R. Gadh, “Virtual and Augmented Reality Technologies for Product Realization,” CIRP Annals, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 471–495, Jan. 1999. [CrossRef]

- P. MILGRAM and F. KISHINO, “A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays,” IEICE Trans Inf Syst, vol. E77-D, no. 12, pp. 1321–1329, Dec. 1994, Accessed: Nov. 26, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://search.ieice.org/bin/summary.php?id=e77-d_12_1321&category=D&year=1994&lang=E&abst=.

- R. Azuma, Y. Baillot, R. Behringer, S. Feiner, S. Julier, and B. MacIntyre, “Recent advances in augmented reality,” IEEE Comput Graph Appl, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 34–47, Nov. 2001. [CrossRef]

- “Virtual reality - Wikipedia.” Accessed: Sep. 12, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_reality.

- “Virtual Reality: The Promising Future of Immersive Technology.” Accessed: Sep. 12, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.g2.com/articles/virtual-reality.

- M. Neges and C. Koch, “Augmented reality supported work instructions for onsite facility maintenance,” Jun. 30, 2016. Accessed: Oct. 10, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/index.php/output/792905/augmented-reality-supported-work-instructions-for-onsite-facility-maintenance.

- Md. F. Rahman, R. Pan, J. Ho, and T.-L. (Bill) Tseng, “A Review of Augmented Reality Technology and its Applications in Digital Manufacturing,” SSRN Electronic Journal, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Palmarini, J. A. Erkoyuncu, R. Roy, and H. Torabmostaedi, “A systematic review of augmented reality applications in maintenance,” Robot Comput Integr Manuf, vol. 49, pp. 215–228, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Booth, A. Sutton, M. Clowes, and M. M.-S. James, “Systematic approaches to a successful literature review,” 2021, Accessed: Nov. 26, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=SiExEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT25&ots=vrXzyg4FZH&sig=ij_jOB6bZgPdfGUfgUdfionJuQo.

- D. Mourtzis, J. Angelopoulos, and N. Panopoulos, “A Framework for Automatic Generation of Augmented Reality Maintenance & Repair Instructions based on Convolutional Neural Networks,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 93, pp. 977–982, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, S. K. Ong, and A. Y. C. Nee, “Multi-modal augmented-reality assembly guidance based on bare-hand interface,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 406–421, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Fiaz and S. K. Jung, “Handcrafted and Deep Trackers: Recent Visual Object Tracking Approaches and Trends,” ACM Comput Surv, vol. 52, no. 2, p. 43, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. De Amicis, A. Ceruti, D. Francia, L. Frizziero, and B. Simões, “Augmented Reality for virtual user manual,” International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 689–697, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Camburn et al., “Design prototyping methods: state of the art in strategies, techniques, and guidelines,” Design Science, vol. 3, p. e13, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Kent, C. Snider, J. Gopsill, and B. Hicks, “Mixed reality in design prototyping: A systematic review,” Des Stud, vol. 77, p. 101046, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Berni and Y. Borgianni, “Applications of Virtual Reality in Engineering and Product Design: Why, What, How, When and Where,” Electronics 2020, Vol. 9, Page 1064, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 1064, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- U. Urbas, R. Vrabič, and N. Vukašinović, “Displaying Product Manufacturing Information in Augmented Reality for Inspection,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 81, pp. 832–837, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Schumann, C. Fuchs, C. Kollatsch, and P. Klimant, “Evaluation of augmented reality supported approaches for product design and production processes,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 97, pp. 160–165, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. T. Ho, J. A. Albajez, J. Santolaria, and J. A. Yagüe-Fabra, “Study of Augmented Reality Based Manufacturing for Further Integration of Quality Control 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review,” Applied Sciences 2022, Vol. 12, Page 1961, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 1961, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, X. An, and N. Sun, “Virtual simulation experiment of the design and manufacture of a beer bottle-defect detection system.,” Virtual Reality & Intelligent Hardware, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 354–367, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Ferraguti et al., “Augmented reality based approach for on-line quality assessment of polished surfaces,” Robot Comput Integr Manuf, vol. 59, pp. 158–167, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Uva, M. Gattullo, V. M. Manghisi, D. Spagnulo, G. L. Cascella, and M. Fiorentino, “Evaluating the effectiveness of spatial augmented reality in smart manufacturing: a solution for manual working stations,” The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2017 94:1, vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 509–521, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Lorenz, S. Knopp, and P. Klimant, “Industrial Augmented Reality: Requirements for an Augmented Reality Maintenance Worker Support System,” IEEE Access, 2018.

- M. Eswaran and M. V. A. R. Bahubalendruni, “Challenges and opportunities on AR/VR technologies for manufacturing systems in the context of industry 4.0: A state of the art review,” J Manuf Syst, vol. 65, pp. 260–278, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Ford and T. Höllerer, “Augmented Reality and the Future of Virtual Workspaces,” https://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/978-1-59904-893-2.ch034, pp. 486–502, Jan. 1AD. [CrossRef]

- P. Rupprecht, H. Kueffner-Mccauley, M. Trimmel, and S. Schlund, “Adaptive Spatial Augmented Reality for Industrial Site Assembly,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 104, pp. 405–410, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Blaga, C. Militaru, A. D. Mezei, and L. Tamas, “Augmented reality integration into MES for connected workers,” Robot Comput Integr Manuf, vol. 68, p. 102057, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Tzimas, G. C. Vosniakos, and E. Matsas, “Machine tool setup instructions in the smart factory using augmented reality: a system construction perspective,” International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 121–136, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- “VR Hardware.” Accessed: Sep. 12, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.hitl.washington.edu/projects/learning_center/pf/whatvr1.htm#id.

- “Top 10 Virtual Reality Software Development Tools.” Accessed: Dec. 01, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://beam.eyeware.tech/top-10-virtual-reality-software-development-tools-gamers/.

- “GitHub - ValveSoftware/openvr: OpenVR SDK.” Accessed: Sep. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/ValveSoftware/openvr.

- “The best 5 VR SDKs for Interactions for Unity & Unreal.” Accessed: Sep. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://xrbootcamp.com/the-best-5-vr-sdk-for-interactions/.

- K. Stecuła, “Virtual Reality Applications Market Analysis—On the Example of Steam Digital Platform,” Informatics 2022, Vol. 9, Page 100, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 100, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Bottani et al., “Wearable and interactive mixed reality solutions for fault diagnosis and assistance in manufacturing systems: Implementation and testing in an aseptic bottling line,” Comput Ind, vol. 128, p. 103429, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Pérez, E. Diez, R. Usamentiaga, and D. F. García, “Industrial robot control and operator training using virtual reality interfaces,” Comput Ind, vol. 109, pp. 114–120, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, Y. Ma, L. Zhang, R. X. Gao, and D. Wu, “Deep learning for smart manufacturing: Methods and applications,” J Manuf Syst, vol. 48, pp. 144–156, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Sahu, C. Young, and R. Rai, “Artificial intelligence (AI) in augmented reality (AR)-assisted manufacturing applications: a review,”, vol. 59, no. 16, pp. 4903–4959, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Dollar, R. Appel, S. Belongie, and P. Perona, “Fast feature pyramids for object detection,” IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, vol. 36, no. 8, pp. 1532–1545, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. B. Park, M. Kim, S. H. Choi, and J. Y. Lee, “Deep learning-based smart task assistance in wearable augmented reality,” Robot Comput Integr Manuf, vol. 63, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Girshick, J. Donahue, T. Darrell, J. Malik, U. C. Berkeley, and J. Malik, “Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation,” Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, vol. 1, p. 5000, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Z. H. Lai, W. Tao, M. C. Leu, and Z. Yin, “Smart augmented reality instructional system for mechanical assembly towards worker-centered intelligent manufacturing,” J Manuf Syst, vol. 55, pp. 69–81, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- “YOLOv5 | PyTorch.” Accessed: Sep. 17, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://pytorch.org/hub/ultralytics_yolov5/.

- J. Lambrecht, L. Kästner, J. Guhl, and J. Krüger, “Towards commissioning, resilience and added value of Augmented Reality in robotics: Overcoming technical obstacles to industrial applicability,” Robot Comput Integr Manuf, vol. 71, p. 102178, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. De Felice, A. R. Cannito, D. Monte, and F. Vitulano, “S.A.M.I.R.: Supporting Tele-Maintenance with Integrated Interaction Using Natural Language and Augmented Reality,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 12936 LNCS, pp. 280–284, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Izquierdo-Domenech, J. Linares-Pellicer, and J. Orta-Lopez, “Towards achieving a high degree of situational awareness and multimodal interaction with AR and semantic AI in industrial applications,” Multimed Tools Appl, vol. 82, no. 10, pp. 15875–15901, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Akbarinasaji and E. Homayounvala, “A novel context-aware augmented reality framework for maintenance systems,” J Ambient Intell Smart Environ, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 315–327, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. J. C. Trappey, C. V. Trappey, M. H. Chao, and C. T. Wu, “VR-enabled engineering consultation chatbot for integrated and intelligent manufacturing services,” J Ind Inf Integr, vol. 26, p. 100331, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Boboc et al., “A VR-Enabled Chatbot Supporting Design and Manufacturing of Large and Complex Power Transformers,” Electronics 2022, Vol. 11, Page 87, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 87, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. VanDerHorn and S. Mahadevan, “Digital Twin: Generalization, characterization and implementation,” Decis Support Syst, vol. 145, p. 113524, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Ong, A. Y. C. Nee, A. W. W. Yew, and N. K. Thanigaivel, “AR-assisted robot welding programming,” Advances in Manufacturing 2019 8:1, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 40–48, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Malik, T. Masood, and A. Bilberg, “Virtual reality in manufacturing: immersive and collaborative artificial-reality in design of human-robot workspace,” vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 22–37, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. V. Wang, L. Wang, M. Lei, and Y. Zhao, “Closed-loop augmented reality towards accurate human-robot collaboration,” CIRP Annals, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 425–428, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Wang et al., “AR/MR Remote Collaboration on Physical Tasks: A Review,” Robot Comput Integr Manuf, vol. 72, p. 102071, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Arevalo and F. Rucker, “Assisting manipulation and grasping in robot teleoperation with augmented reality visual cues,” Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Hart and L. E. Staveland, “Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of Empirical and Theoretical Research,” Advances in Psychology, vol. 52, no. C, pp. 139–183, Jan. 1988. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Choi, M. Kim, and J. Y. Lee, “Situation-dependent remote AR collaborations: Image-based collaboration using a 3D perspective map and live video-based collaboration with a synchronized VR mode,” Comput Ind, vol. 101, pp. 51–66, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Ni, A. Y. C. Nee, S. K. Ong, H. Li, C. Zhu, and A. Song, “Point cloud augmented virtual reality environment with haptic constraints for teleoperation,” Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control, vol. 40, no. 15, pp. 4091–4104, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Li, P. Zheng, S. Li, Y. Pang, and C. K. M. Lee, “AR-assisted digital twin-enabled robot collaborative manufacturing system with human-in-the-loop,” Robot Comput Integr Manuf, vol. 76, p. 102321, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Choi et al., “An integrated mixed reality system for safety-aware human-robot collaboration using deep learning and digital twin generation,” Robot Comput Integr Manuf, vol. 73, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Marino, L. Barbieri, B. Colacino, A. K. Fleri, and F. Bruno, “An Augmented Reality inspection tool to support workers in Industry 4.0 environments,” Comput Ind, vol. 127, p. 103412, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Tatić and B. Tešić, “The application of augmented reality technologies for the improvement of occupational safety in an industrial environment,” Comput Ind, vol. 85, pp. 1–10, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Durchon, M. Preda, T. Zaharia, and Y. Grall, “Challenges in Applying Deep Learning to Augmented Reality for Manufacturing,” Proceedings - Web3D 2022: 27th ACM Conference on 3D Web Technology, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Holm, O. Danielsson, A. Syberfeldt, P. Moore, and L. Wang, “Adaptive instructions to novice shop-floor operators using Augmented Reality,”. vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 362–374, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]