Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

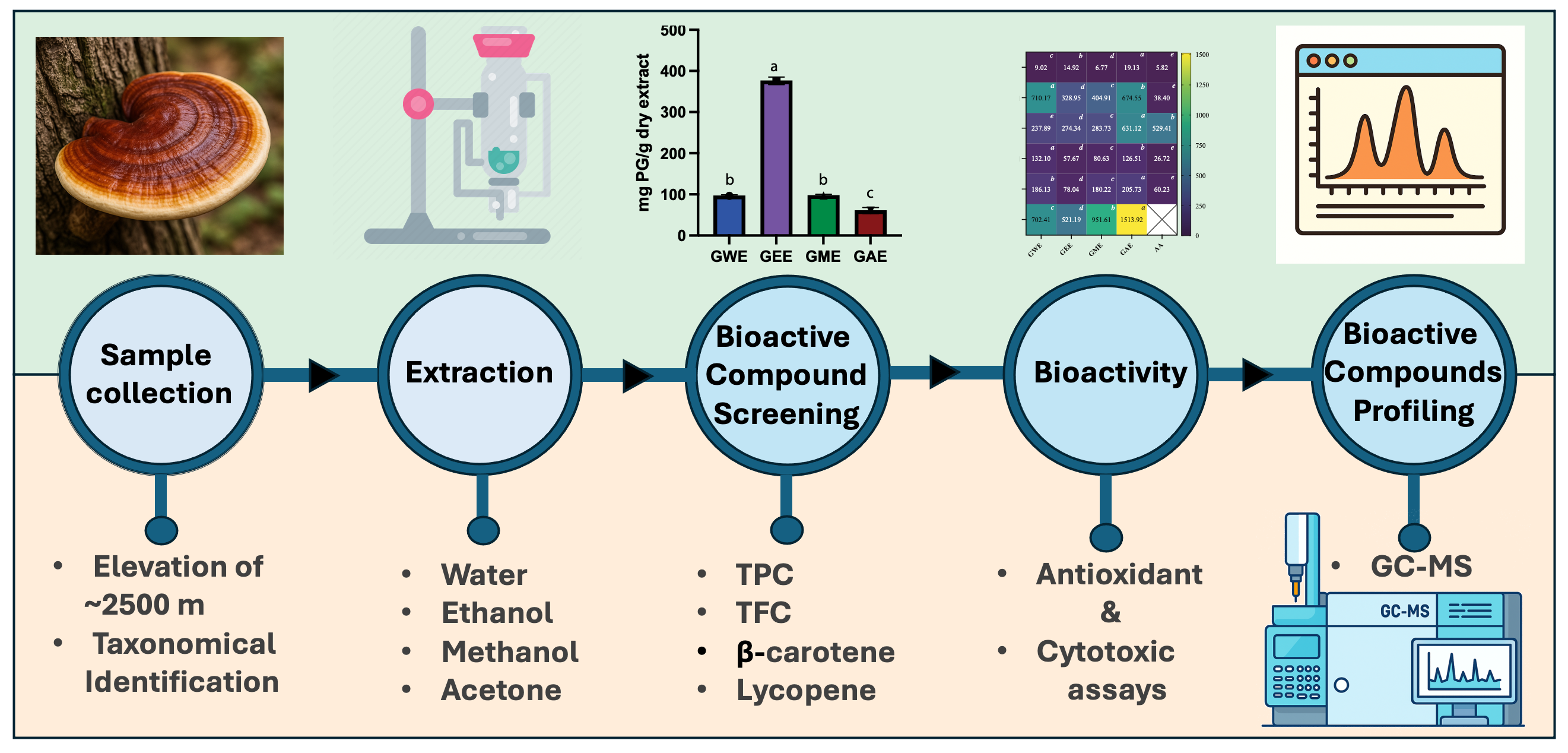

2. Materials and Methods

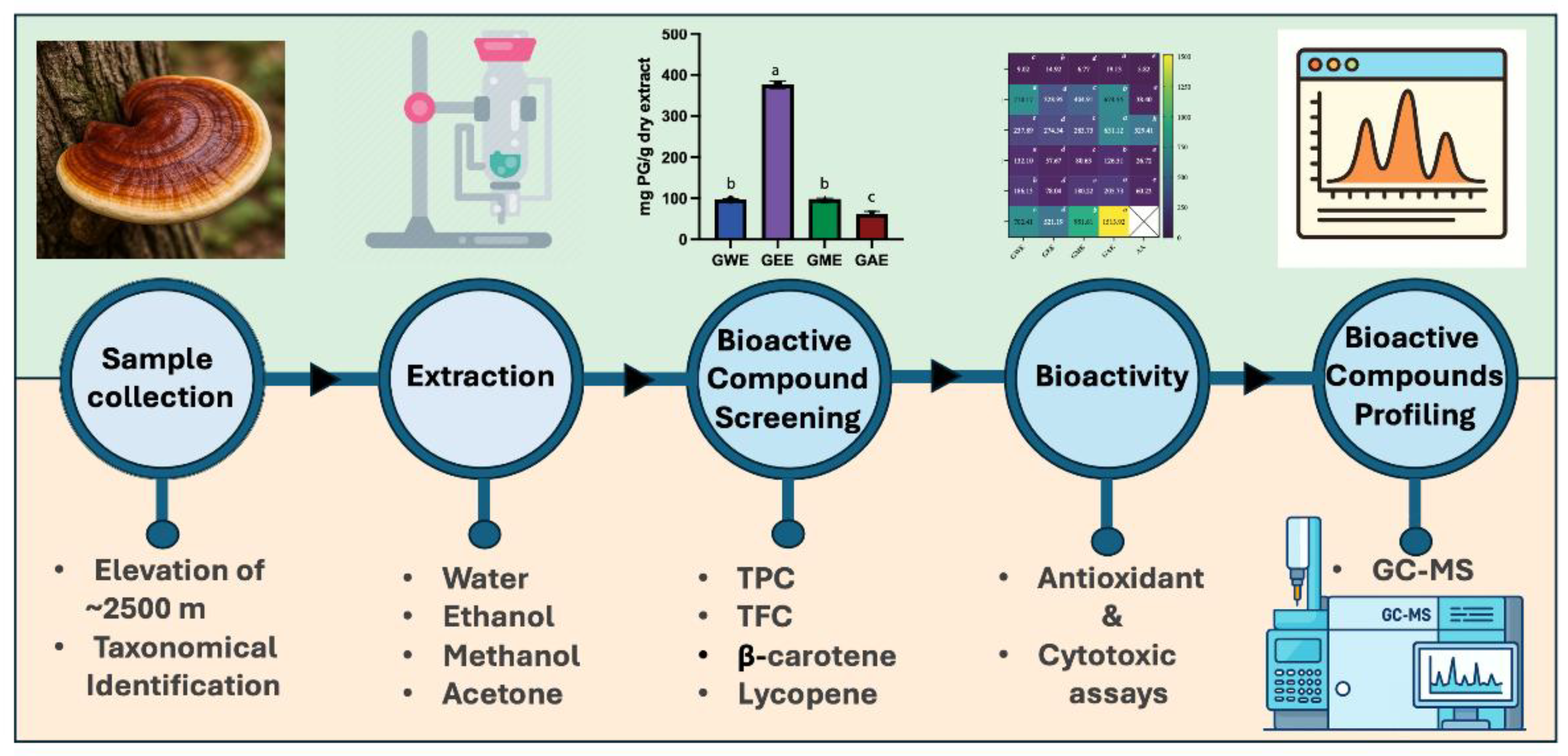

2.1. Collection and Identification

2.2. Sample Preparation and Extraction

2.3. Estimation of Total Phenolic, Flavonoid, β-carotene and Lycopene

2.3.1. Total Phenolic Content

2.3.2. Total Flavonoid Content

2.3.3. Estimation of β-Carotene and Lycopene Content

2.4. Determination of In Vitro Antioxidant Activities

2.4.1. DPPH (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl) Assay

2.4.2. Nitric Oxide Radical Scavenging Assay

2.4.3. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Assay

2.4.4. Superoxide Radical Scavenging Assay

2.4.5. Reducing Power Assay

2.5. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.6. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Extraction Yield

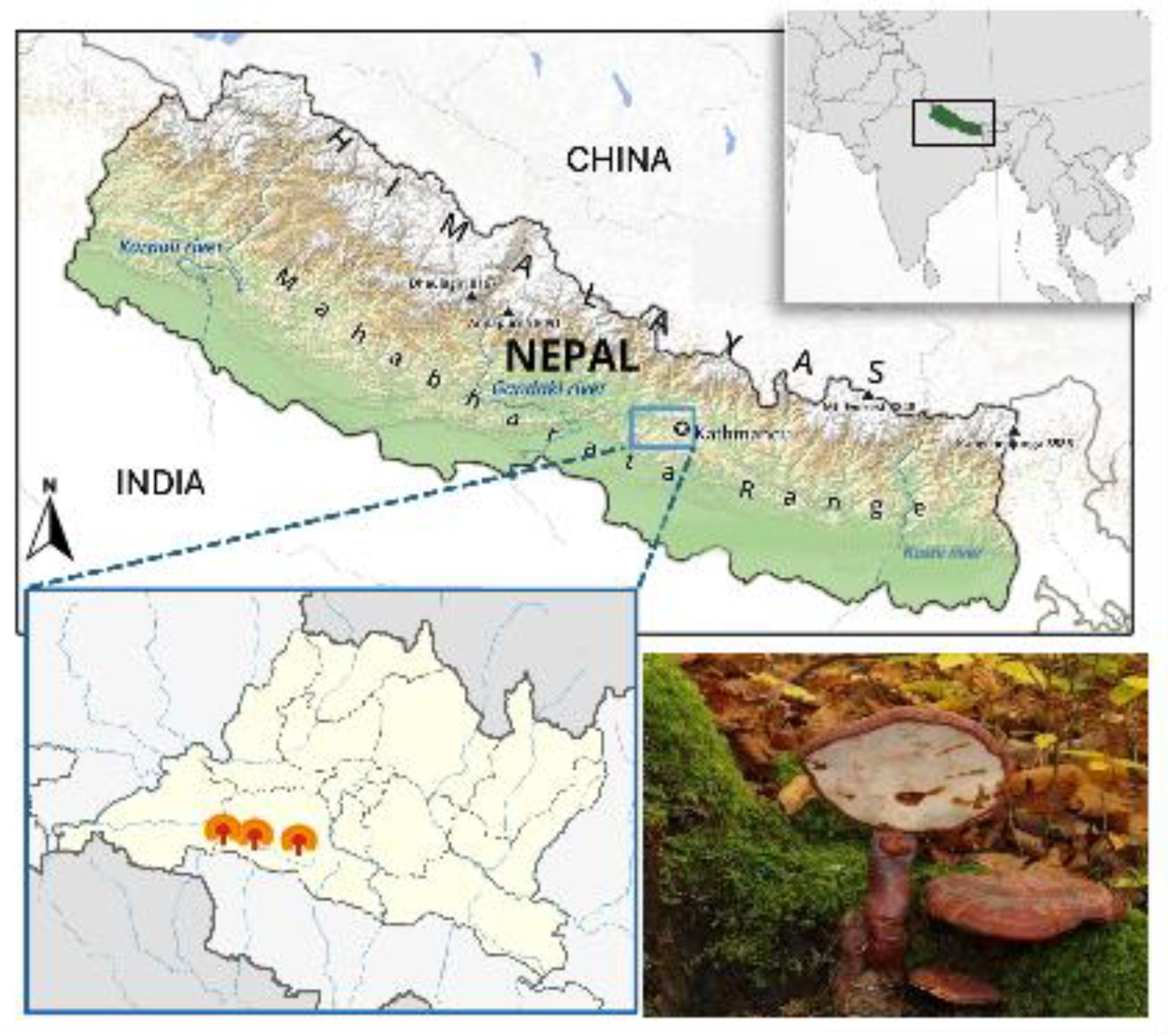

3.1. Estimation of Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content

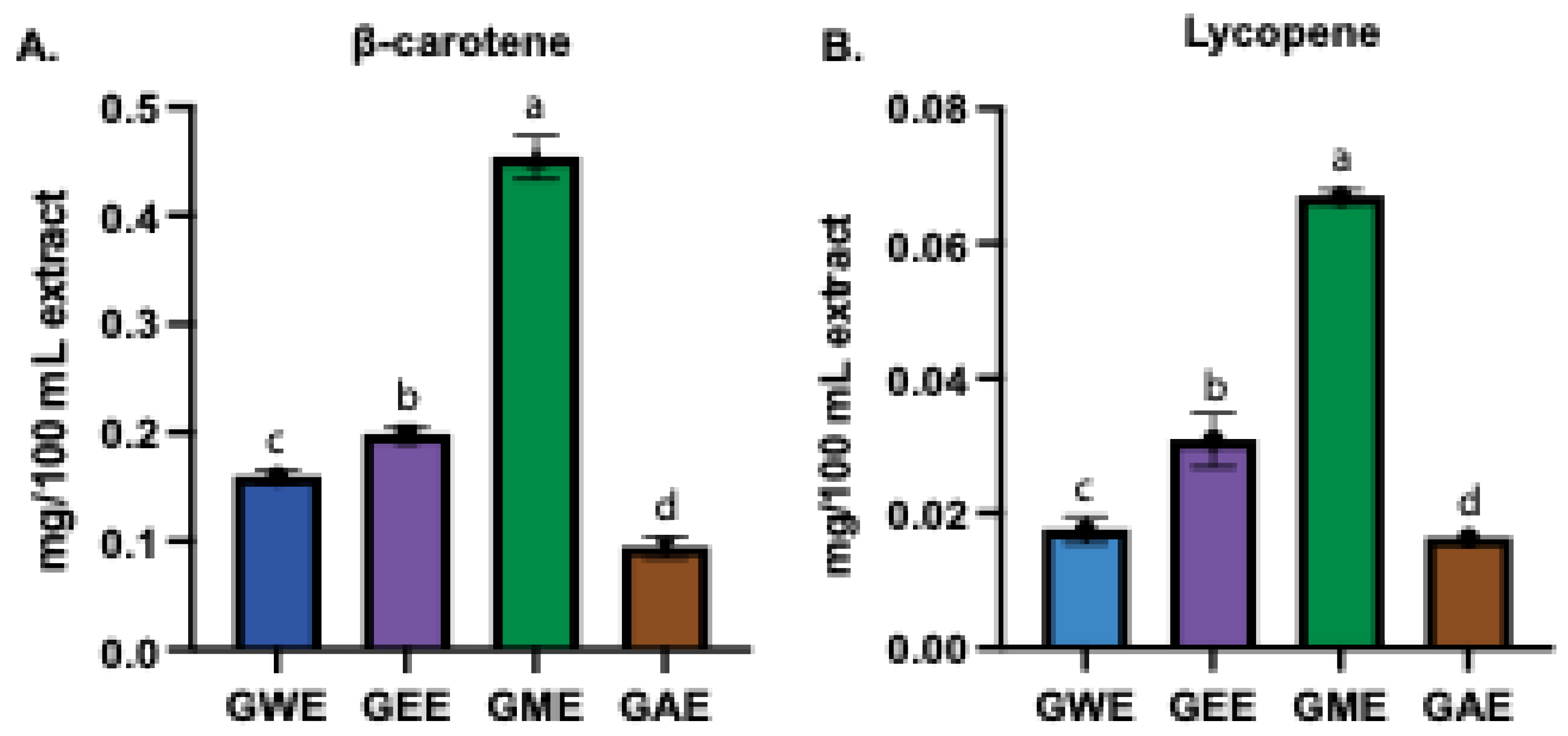

3.2. Estimation of β-Carotene and Lycopene

3.3. Comparative In-Vitro Antioxidant Activities

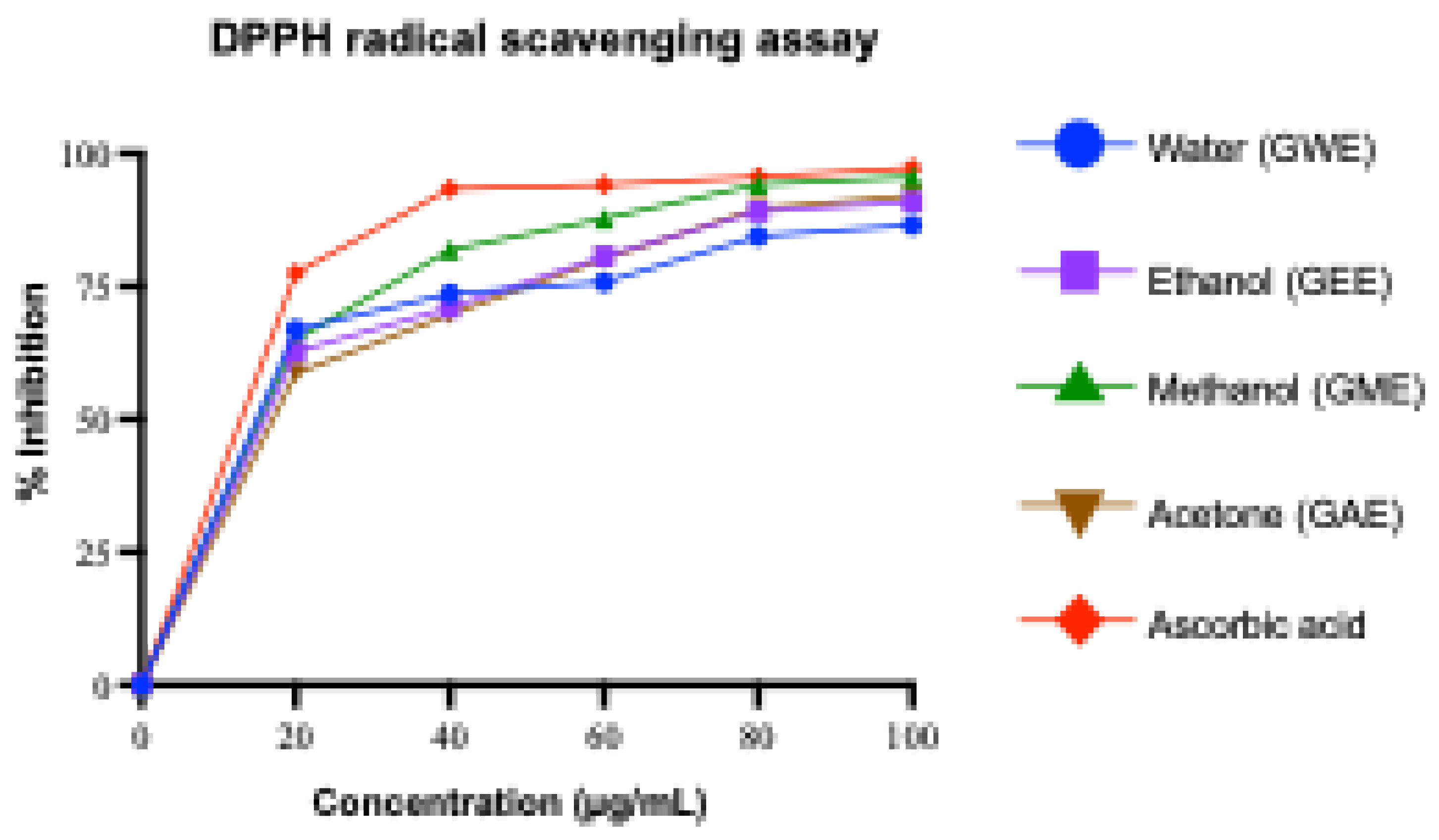

3.3.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

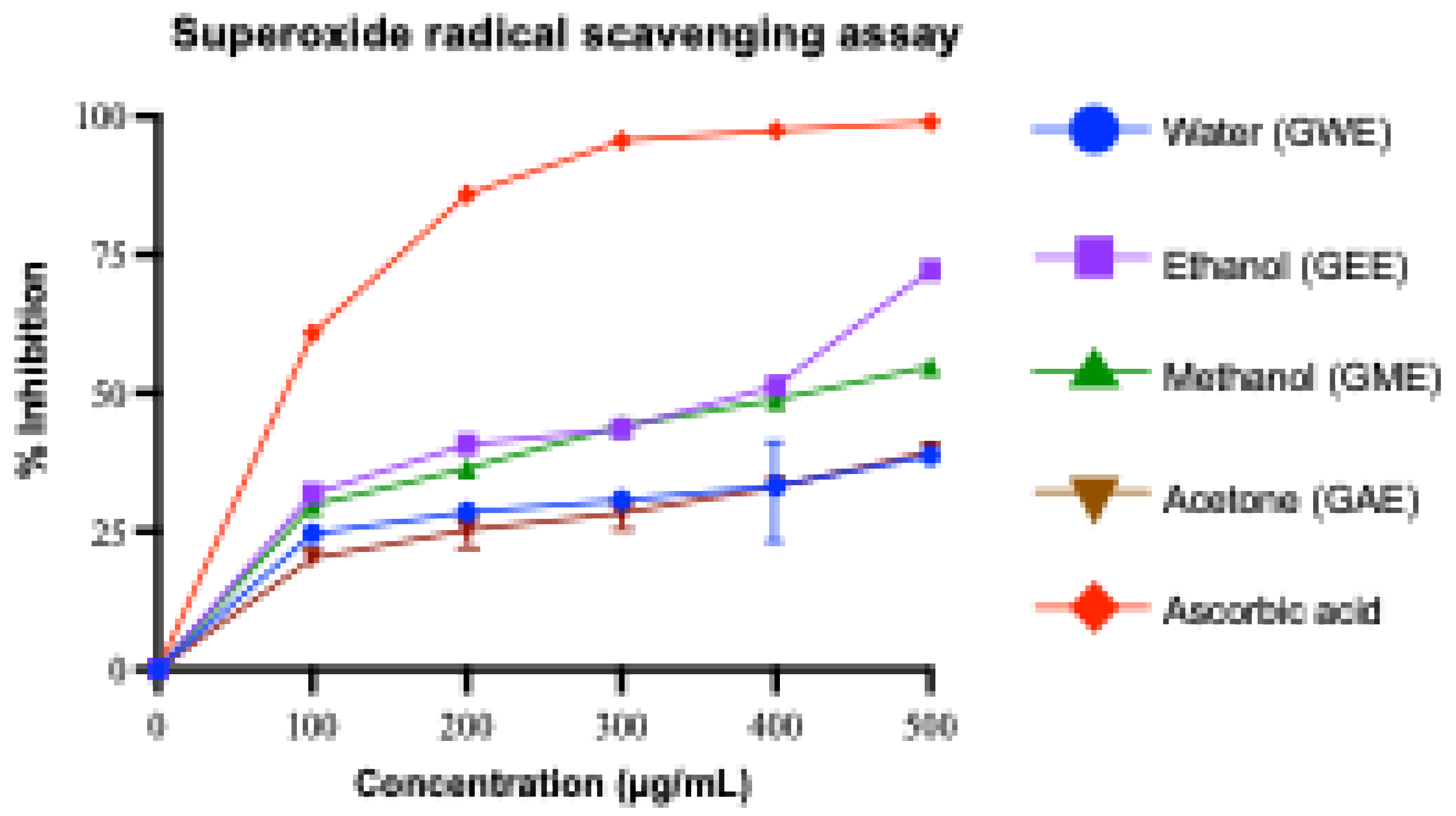

3.3.2. Superoxide Radical Scavenging Activity

3.3.3. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity

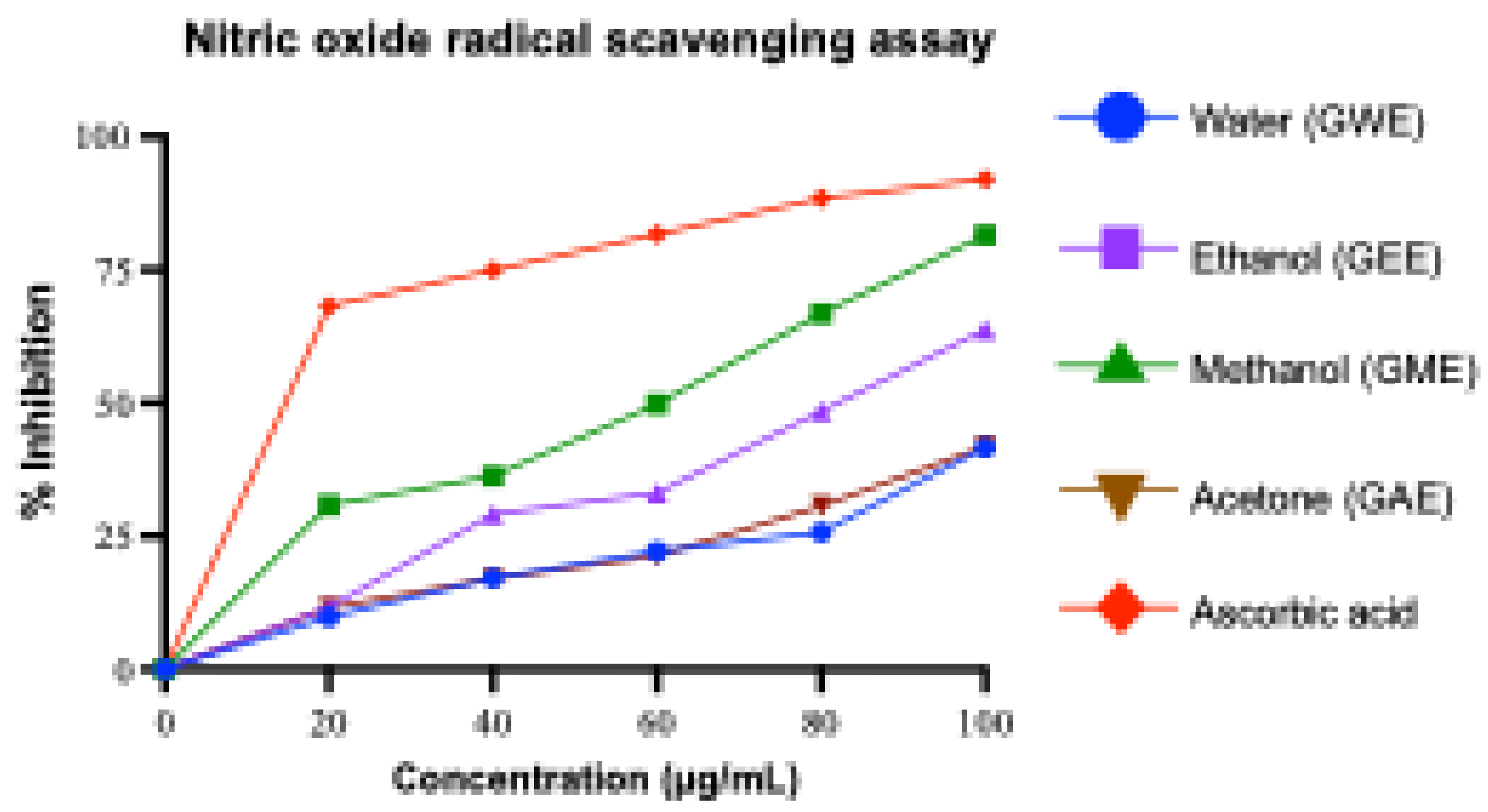

3.3.4. Nitric Oxide Radical Scavenging Activity

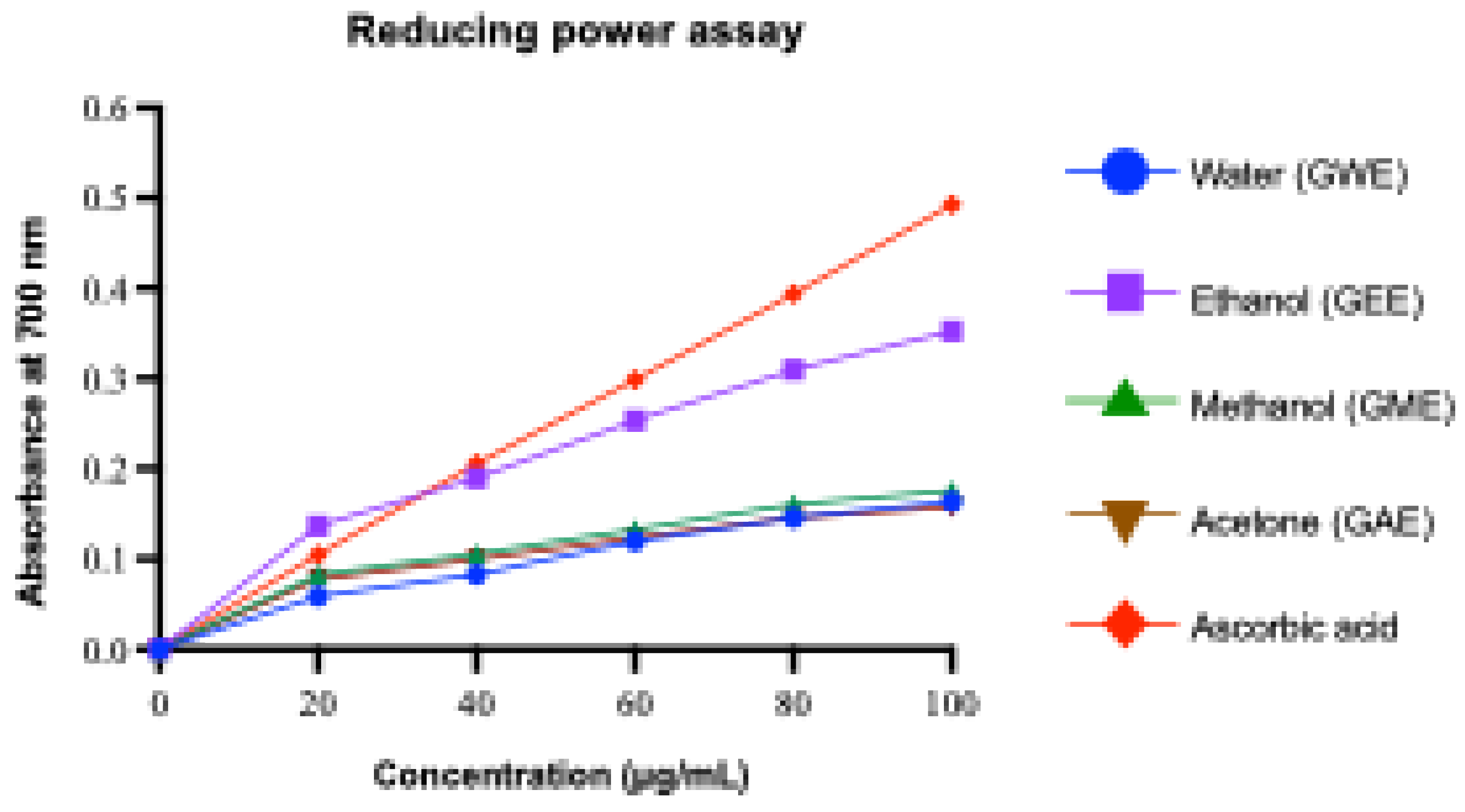

3.3.5. Reducing Power Assay

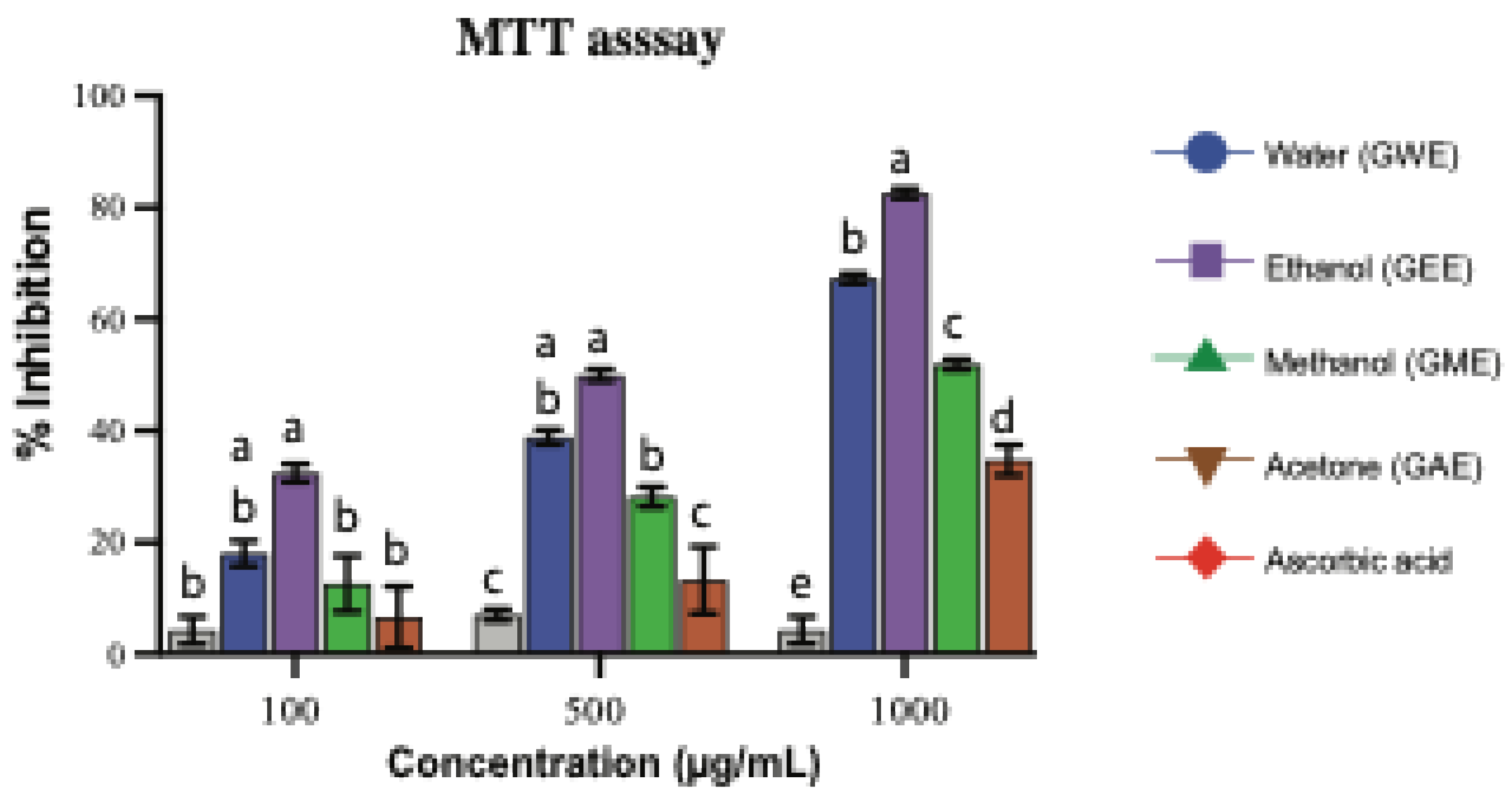

3.4. MTT-Based Cytotoxicity Assay in HeLa Cells

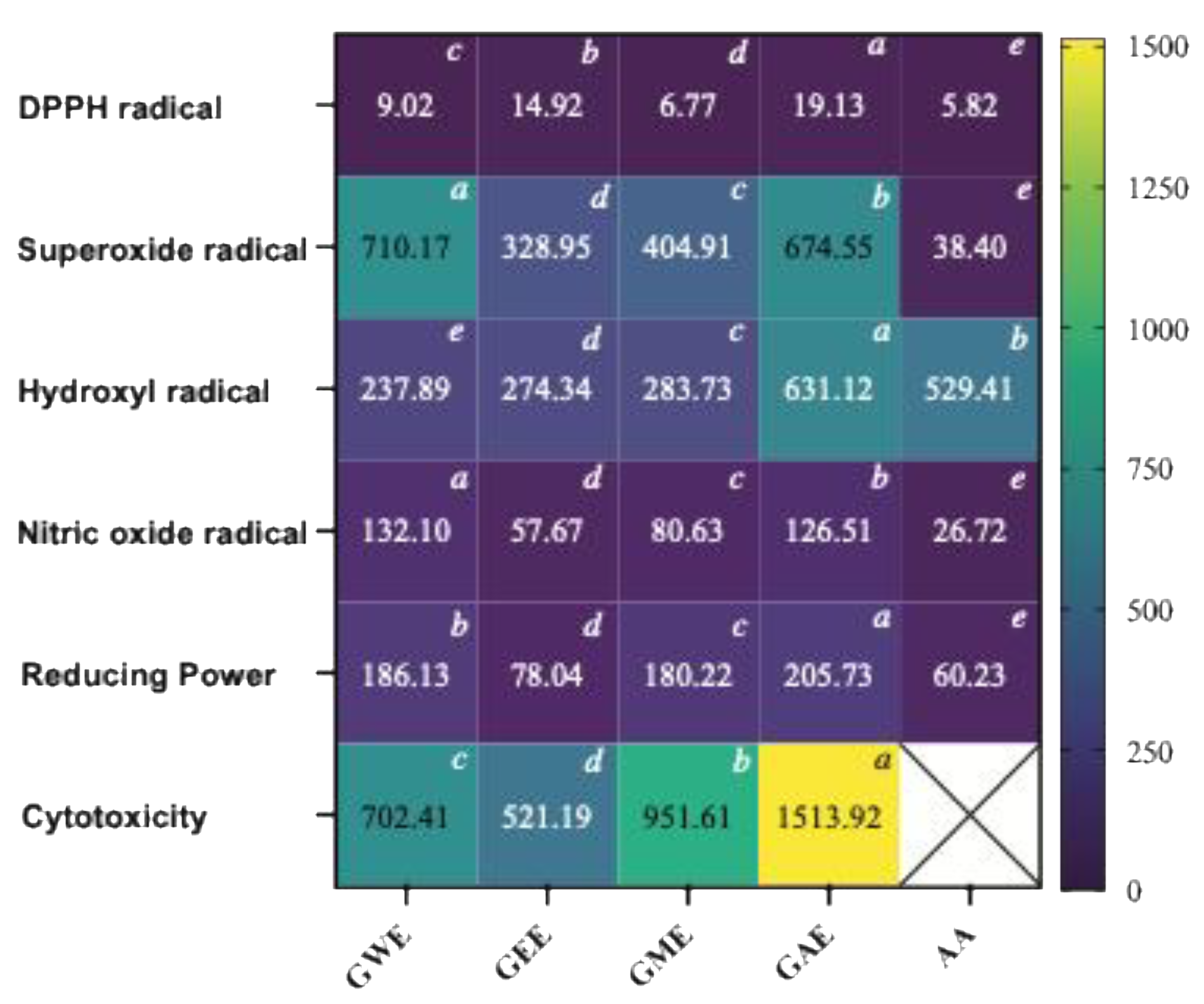

3.5. IC50 Comparison of Extraction Solvents for Antioxidant and Cytotoxicity Activities

3.6. Solvent-Dependent Variation in Bioactive Compounds via GC-MS Profiling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, L.W.; Cao, Y.; Wu, S.H.; Vlasák, J.; Li, D.W.; Li, M.J.; Dai, Y.C. Global Diversity of the Ganoderma Lucidum Complex (Ganodermataceae, Polyporales) Inferred from Morphology and Multilocus Phylogeny. Phytochemistry 2015, 114, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, K.S.; Kao, C.H.J.; Xu, Y.; Glucina, M.P.; Paterson, R.R.M.; Ferguson, L.R. From 2000 Years of Ganoderma Lucidum to Recent Developments in Nutraceuticals. Phytochemistry 2015, 114, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekiz, E.; Oz, E.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Proestos, C.; Brennan, C.; Zeng, M.; Tomasevic, I.; Elobeid, T.; Çadırcı, K.; Bayrak, M.; et al. Exploring the Potential Medicinal Benefits of Ganoderma Lucidum: From Metabolic Disorders to Coronavirus Infections. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Tian, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, Z. Chemodiversity, Pharmacological Activity, and Biosynthesis of Specialized Metabolites from Medicinal Model Fungi Ganoderma Lucidum. Chinese Medicine 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baby, S.; Johnson, A.J.; Govindan, B. Secondary Metabolites from Ganoderma. Phytochemistry 2015, 114, 66–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Chang, Q.; Wong, L.K.; Chong, F.S.; Li, R.C. Triterpene Antioxidants from Ganoderma Lucidum. Phytother Res. 1999, 529–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, J.W.M.; Gohel, M.D.I.; Yuen, J.W.M.; Gohel, M.D.I. Anticancer Effects of Ganoderma Lucidum: A Review of Scientific Evidence. Nutr Cancer. 2005, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettre, D.P. Pharmacognostic Standardization of Ganoderma Lucidum: A Commercially Explored Medicinal Mushroom. 2015.

- Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Heleno, S.A.; Reis, F.S.; Stojkovic, D.; Queiroz, M.J.R.P.; Vasconcelos, M.H.; Sokovic, M. Chemical Features of Ganoderma Polysaccharides with Antioxidant, Antitumor and Antimicrobial Activities. Phytochemistry 2015, 114, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Padmanaban, M.; Uthayakumar, V. Isolation, Structural Characterization and Antioxidant Activities of Polysaccharide from Ganoderma Lucidum (Higher Basidiomycetes). American Journal of Bio and Life Sci. 2015, 3, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Heleno, S.A.; Barros, L.; Martins, A.; João, M.; Queiroz, R.P. Fruiting Body, Spores and in Vitro Produced Mycelium of Ganoderma Lucidum from Northeast Portugal: A Comparative Study of the Antioxidant Potential of Phenolic and Polysaccharidic Extracts. Food Research Int. 2012, 135-140,.

- Niedermeyer, T.H.J.; Lindequist, U.; Mentel, R.; Go, D.; Schmidt, E.; Thurow, K.; Lalk, M. Antiviral Terpenoid Constituents of Ganoderma Pfeifferi. J Nat Prod. 2005, 1728–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Montemayor, M.M.; Ling, T.; Suárez-Arroyo, I.J.; Ortiz-Soto, G.; Santiago-Negrón, C.L.; Lacourt-Ventura, M.Y.; Valentín-Acevedo, A.; Lang, W.H.; Rivas, F. Identification of Biologically Active Ganoderma Lucidum Compounds and Synthesis of Improved Derivatives That Confer Anti-Cancer Activities in Vitro. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasnat, M.A.; Pervin, M.; Cha, K.M.; Kim, S.K.; Lim, B.O. Anti-Inflammatory Activity on Mice of Extract of Ganoderma Lucidum Grown on Rice via Modulation of MAPK and NF-ΚB Pathways. Phytochemistry 2015, 114, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, K.; Shrestha, H.L.; Murthy, M.S.R.; Bajracharya, B.; Shrestha, B.; Gilani, H.; Pradhan, S.; Dangol, B. Development of 2010 National Land Cover Database for the Nepal. J Environ Manage 2015, 148, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai Bang, T.; Suhara, H.; Doi, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Fukami, K.; Parajuli, G.P.; Katakura, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Watanabe, K.; Adhikari, M.K.; et al. Wild Mushrooms in Nepal: Some Potential Candidates as Antioxidant and ACE-Inhibition Sources. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrakar, S.; Tran, H.B.; Nishida, M.; Kaifuchi, S.; Suhara, H.; Doi, K.; Fukami, K.; Parajuli, G.P.; Shimizu, K. Antioxidative Activities of 62 Wild Mushrooms from Nepal and the Phenolic Profile of Some Selected Species. J Nat Med 2016, 70, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.; Bhattarai, S.; Devkota, S.; Larsen, H.O. Collection and Use of Wild Edible Fungi in Nepal. Econ Bot. 2008.

- Devkota, S.; Fang, W.; Arunachalam, K.; Phyo, K.M.M.; Shakya, B. Systematic Review of Fungi, Their Diversity and Role in Ecosystem Services from the Far Eastern Himalayan Landscape (FHL). Heliyon 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, M.K. Mushrooms of Nepal; Durrieu, G. , Cotter, H.V.T., Eds.; Self-Published: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Paudel, P.K.; Bhattarai, B.P.; Kindlmann, P. An Overview of the Biodiversity in Nepal. In Himalayan Biodiversity in the Changing World; Springer Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–40 ISBN 9789400718029.

- Pan, L.; Yang, N.; Sui, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, L.; Mu, L.; Tang, Z. Altitudinal Variation on Metabolites, Elements, and Antioxidant Activities of Medicinal Plant Asarum. Metabolites 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, D. Secondary Metabolites as a Survival Strategy in Plants of High Mountain Habitats. Bol Latinoam Caribe Plantas Med Aromat 2019, 18, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.P.; Kareparamban, J. a; Nikam, P.H.; Kadam, V.J. Spectrophotometric Estimation of Ferulic Acid from Ferula Asafoetida by Folin—Ciocalteu ’ s Reagent. Der Pharmacia Sinica 2012, 3, 680–684. [Google Scholar]

- Shraim, A.M.; Ahmed, T.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Hijji, Y.M. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content by Aluminum Chloride Assay: A Critical Evaluation. LWT 2021, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, V.; Rana, S.; Sagar, A. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Methanolic Extract of Ganoderma Lucidum ( Curt.) P. Karst. 2016, 51–54.

- Chang, S.T.; Wu, J.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Kang, P.L.; Yang, N.S.; Shyur, L.F. Antioxidant Activity of Extracts from Acacia Confusa Bark and Heartwood. J Agric Food Chem 2001, 49, 3420–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, N.; Bristi, N.J. Review on in Vivo and in Vitro Methods Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Jia, L.; Kan, J.; Jin, C.H. In Vitro and in Vivo Antioxidant Activity of Ethanolic Extract of White Button Mushroom (Agaricus Bisporus). Food Chem Toxicol 2013, 51, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jemli, M.; Kamal, R.; Marmouzi, I.; Zerrouki, A.; Cherrah, Y.; Alaoui, K. Radical-Scavenging Activity and Ferric Reducing Ability of Juniperus Thurifera (L.), J. Oxycedrus (L.), J. Phoenicea (L.) and Tetraclinis Articulata (L.). Adv Pharmacol Sci 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Luo, X.G.; He, J.F.; Wang, N.; Zhou, H.; Yang, P.L.; Zhang, T.C. Induction of Apoptosis in Human Cervical Carcinoma Hela Cells by Active Compounds from Hypericum Ascyron L. Oncol Lett 2018, 15, 3944–3950. Oncol Lett 2018, 15, 3944–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Dhakal, N. Analysis of Variations in Biomolecules during Various Growth Phases of Freshwater Microalgae Chlorella Sp. Applied Food Biotechnology 2023, 10, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.D.; Angkawijaya, A.E.; Tran-Nguyen, P.L.; Huynh, L.H.; Soetaredjo, F.E.; Ismadji, S.; Ju, Y.H. Effect of Extraction Solvent on Total Phenol Content, Total Flavonoid Content, and Antioxidant Activity of Limnophila Aromatica. J Food Drug Anal 2014, 22, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Martín, E.; Forbes-Hernández, T.; Romero, A.; Cianciosi, D.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Influence of the Extraction Method on the Recovery of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Food Industry By-Products. Food Chem, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzer, M.; Kiese, S.; Tybussek, T.; Herfellner, T.; Schneider, F.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Eisner, P. Radical Scavenging Mechanisms of Phenolic Compounds: A Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) Study. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Sarikurkcu, C.; Gunes, E.; Uysal, A.; Ceylan, R.; Uysal, S.; Gungor, H.; Aktumsek, A. Two Ganoderma Species: Profiling of Phenolic Compounds by HPLC-DAD, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Inhibitory Activities on Key Enzymes Linked to Diabetes Mellitus, Alzheimer’s Disease and Skin Disorders. Food Funct 2015, 6, 2794–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Özyürek, M.; Güçlü, K.; Çapanoʇlu, E. Antioxidant Activity/Capacity Measurement. 1. Classification, Physicochemical Principles, Mechanisms, and Electron Transfer (ET)-Based Assays. J Agric Food Chem 2016, 64, 997–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Bristi, N.J.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in Vivo and in Vitro Methods Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, L.; Sources, D.; Significance, N. Polyphenols: Chemistry, Dietary Sources, Metabolism, and Nutritional Significance. Nutr Rev 1998, 56, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, M.A.; Sonboli, A. Antioxidant, Free Radical Scavenging Activities of Salvia Brachyantha and Its Protective Effect against Oxidative Cardiac Cell Injury. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2010, 48, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.C.; Kim, I.G. Ganoderma Lucidum Extract Protects DNA from Strand Breakage Caused by Hydroxyl Radical and UV Irradiation. Int J Mol Med 1999, 4, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmi, B.; Ajith, T. a; Sheena, N.; Gunapalan, N.; Janardhanan, K.K. Antiperoxidative, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antimutagenic Activities of Ethanol Extract of the Mycelium of Ganoderma Lucidum Occurring in South India. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen 2003, Suppl 1, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Kwon, H.; Jeong, H.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, S.Y.; Baek, S.J.; Surh, Y.J. Inhibition of Lipid Peroxidation and Oxidative DNA Damage by Ganoderma Lucidum. Phytotherapy Research 2001, 15, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacher, P.; Beckman, J.S.; Liaudet, L. Nitric Oxide and Peroxynitrite in Health and Disease; Physiol Rev. 2007, 315-424. [CrossRef]

- Vamanu, E.; Nita, S. Antioxidant Capacity and the Correlation with Major Phenolic Compounds, Anthocyanin, and Tocopherol Content in Various Extracts from the Wild Edible Boletus Edulis Mushroom. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakumar, T.; Thomas, P.A.; Geraldine, P. In-Vitro Antioxidant Activities of an Ethanolic Extract of the Oyster Mushroom, Pleurotus Ostreatus. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2009, 10, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Ferreira, M.J.; Queirós, B.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Baptista, P. Total Phenols, Ascorbic Acid, B-Carotene and Lycopene in Portuguese Wild Edible Mushrooms and Their Antioxidant Activities. Food Chem 2007, 103, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, M.; Rajasekaran, M.; Kalaimagal, C. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Ethanolic Extract of a Medicinal Mushroom, Ganoderma Lucidum; 2011.

- Abdullah, N.; Ismail, S.M.; Aminudin, N.; Shuib, A.S.; Lau, B.F. Evaluation of Selected Culinary-Medicinal Mushrooms for Antioxidant and ACE Inhibitory Activities. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.S.H.; Lim, S.L. Ferric Reducing Capacity Versus Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power for Measuring Total Antioxidant Capacity. Lab Med 2013, 44, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhantayeva, A.; Tursynova, N.; Kolpek, A.; Aibuldinov, Y.; Tursynova, A.; Mashan, T.; Mukazhanova, Z.; Ibrayeva, M.; Zeinuldina, A.; Nurlybayeva, A.; et al. Phytochemical Profiling, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Potentials of Ethanol and Ethyl Acetate Extracts of Chamaenerion Latifolium L. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant Phenolics: Extraction, Analysis and Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, T.; Destandau, E.; Lesellier, E. Selective Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Plants Using Recent Extraction Techniques: J Chromatogr A 2021, 1635:461770. [CrossRef]

- Thang, T.D.; Kuo, P.C.; Hwang, T.L.; Yang, M.L.; Ngoc, N.T.B.; Han, T.T.N.; Lin, C.W.; Wu, T.S. Triterpenoids and Steroids from Ganoderma Mastoporum and Their Inhibitory Effects on Superoxide Anion Generation and Elastase Release. Molecules 2013, 18, 14285–14292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Wang, L.W.; Zheng, H.C.; Damirin, A.; Ma, C.M. Cytotoxic Constituents of Lasiosphaera Fenzlii on Different Cell Lines and the Synergistic Effects with Paclitaxel. Nat Prod Res 2016, 30, 1862–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Ligonio, A.; López-Monteon, A.; Lagunes-Castro, M. de la S.; Suárez-Medellín, J.; Espinoza, C.; Mendoza, G.; Trigos, Á. In Vitro Expression of Toll-like Receptors and Proinflammatory Molecules Induced by Ergosta-7,22-Dien-3-One Isolated from a Wild Mexican Strain of Ganoderma Oerstedii (Agaricomycetes). Int J Med Mushrooms 2017, 19, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivošija, S.; Nastić, N.; Karadžić Banjac, M.; Kovačević, S.; Podunavac-Kuzmanović, S.; Vidović, S. Supercritical Extraction and Compound Profiling of Diverse Edible Mushroom Species. Foods 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, R.; Kumar, D. Study of Chemical Composition in Wild Edible Mushroom Pleurotus Cornucopiae (Paulet) from Himachal Pradesh, India by Using Fourier Transforms Infrared Spectrometry (FTIR), Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GCMS) and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF). Biological Forum—An International Journal 2015.

- Akwu, N.A.; Naidoo, Y.; Singh, M.; Lin, J.; Aribisala, J.O.; Sabiu, S.; Lekhooa, M.; Aremu, A.O. Phytochemistry, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Grewia Lasiocarpa E. Mey. Ex Harv. Fungal Endophytes: A Computational and Experimental Validation Study. Chem Biodivers 2025. [CrossRef]

- Das Gupta, S.; Suh, N. Tocopherols in Cancer: An Update. Mol Nutr Food Res 2016, 60, 1354–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; He, Y.; Cui, X.X.; Goodin, S.; Wang, H.; Du, Z.Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, K.; Tony Kong, A.N.; Dipaola, R.S.; et al. Potent Inhibitory Effect of β-Tocopherol on Prostate Cancer Cells Cultured in Vitro and Grown as Xenograft Tumors in Vivo. J Agric Food Chem 2014, 62, 10752–10758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, K.; Daśko, M.; Ciupak, O.; Kubiński, K.; Rachon, J.; Demkowicz, S. Novel 1,2,4-Oxadiazole Derivatives in Drug Discovery. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.; Świątek, P. Antimicrobial Activity of 1,3,4-Oxadiazole Derivatives. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwach, A.; Verma, P.K. Therapeutic Potential of Oxadiazole or Furadiazole Containing Compounds. BMC Chem 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrsam, D.; Porta, F.; Mori, M.; Meyer Zu Schwabedissen, H.E.; Via, L.D.; Garcia-Argaez, A.N.; Basile, L.; Meneghetti, F.; Villa, S.; Gelain, A. Unravelling the Antiproliferative Activity of 1,2,5-Oxadiazole Derivatives. Anticancer Res 2019, 39, 3453–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczynski, M.; Kudelko, A. Synthesis and Biological Activity of 1,3,4-Oxadiazoles Used in Medicine and Agriculture. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.C.; Pan, Q.; Xu, X.; Wei, X.; Lei, X.; Zhang, P. Structurally Diverse Steroids from an Endophyte of Aspergillus Tennesseensis 1022LEF Attenuates LPS-Induced Inflammatory Response through the Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway. Chem Biol Interact 2022, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Cheng, X.L.; Cui, J.H.; Yan, X.R.; Wei, F.; Bai, X.; Lin, R.C. Effect of Ergosta-4,6,8(14),22-Tetraen-3-One (Ergone) on Adenine-Induced Chronic Renal Failure Rat: A Serum Metabonomic Study Based on Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography/High-Sensitivity Mass Spectrometry Coupled with MassLynx i-FIT Algorithm. Clinica Chimica Acta 2012, 413, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Shen, X.; Chao, X.; Ho, C.C.; Cheng, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, R.C.; Du, K.J.; Luo, W.J.; Chen, J.Y.; et al. Ergosta-4,6,8(14),22-Tetraen-3-One Induces G2/M Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma HepG2 Cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2011, 1810, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilkhet, S.; Vongthip, W.; Lertpatipanpong, P.; Prasansuklab, A.; Tencomnao, T.; Chuchawankul, S.; Baek, S.J. Ergosterol Inhibits the Proliferation of Breast Cancer Cells by Suppressing AKT/GSK-3beta/Beta-Catenin Pathway. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, S.; Fleurat-Lessard, P.; Cruz, R.G.; Lafarge, C.; Grangeteau, C.; Yahou, F.; Gerbeau-Pissot, P.; Abrahão Júnior, O.; Gervais, P.; Simon-Plas, F.; et al. Antioxidant Properties of Ergosterol and Its Role in Yeast Resistance to Oxidation. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangsinth, P.; Sharika, R.; Pattarachotanant, N.; Duangjan, C.; Wongwan, C.; Sillapachaiyaporn, C.; Nilkhet, S.; Wongsirojkul, N.; Prasansuklab, A.; Tencomnao, T.; et al. Potential Beneficial Effects and Pharmacological Properties of Ergosterol, a Common Bioactive Compound in Edible Mushrooms. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cao, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Ferruginol Restores SIRT1-PGC-1α-Mediated Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Fatty Acid Oxidation for the Treatment of DOX-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varbanov, M.; Philippot, S.; González-Cardenete, M.A. Anticoronavirus Evaluation of Antimicrobial Diterpenoids: Application of New Ferruginol Analogues. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bispo de Jesus, M.; Zambuzzi, W.F.; Ruela de Sousa, R.R.; Areche, C.; Santos de Souza, A.C.; Aoyama, H.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Monteiro de Souza Brito, A.R.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; et al. Ferruginol Suppresses Survival Signaling Pathways in Androgen-Independent Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Biochimie 2008, 90, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, A.M.; Al-Qurainy, F.; Tarroum, M.; Khan, S.; Nadeem, M.; Shaikhaldein, H.O.; Alansi, S. Phytochemical Compound Profile and the Estimation of the Ferruginol Compound in Different Parts (Roots, Leaves, and Seeds) of Juniperus Procera. Separations 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; González-Cardenete, M.A.; Prieto-Garcia, J.M. In Vitro Cytotoxic Effects of Ferruginol Analogues in Sk-MEL28 Human Melanoma Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bispo de Jesus, M.; Zambuzzi, W.F.; Ruela de Sousa, R.R.; Areche, C.; Santos de Souza, A.C.; Aoyama, H.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Monteiro de Souza Brito, A.R.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; et al. Ferruginol Suppresses Survival Signaling Pathways in Androgen-Independent Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Biochimie 2008, 90, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.T.; Tung, Y.T.; Kuo, Y.H.; Lin, C.C.; Wu, J.H. Ferruginol Inhibits Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Growth by Inducing Caspase-Associated Apoptosis. Integr Cancer Ther 2015, 14, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cao, G.; Ding, D.; Li, F.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. Ferruginol Prevents Degeneration of Dopaminergic Neurons by Enhancing Clearance of α-Synuclein in Neuronal Cells. Fitoterapia 2022, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sediva, A.; Orlicky, M.; Vrabcova, P.; Klocperk, A.; Kalina, T.; Fujiwara, H.; Hsu, F.-F.; Bambouskova, M. Geranylgeraniol Supplementation Leads to an Improvement in Inflammatory Parameters and Reversal of the Disease Specific Protein Signature in Patients with Hyper-IgD Syndrome 2024, doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.17.24309492.

- Gheith, R.; Sharp, M.; Stefan, M.; Ottinger, C.; Lowery, R.; Wilson, J. The Effects of Geranylgeraniol on Blood Safety and Sex Hormone Profiles in Healthy Adults: A Dose-Escalation, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutraceuticals 2023, 3, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.; Elmassry, M.M.; Cao, J.J.; Kaur, G.; Dufour, J.M.; Hamood, A.N.; Shen, C.L. Beneficial Effect of Dietary Geranylgeraniol on Glucose Homeostasis and Bone Microstructure in Obese Mice Is Associated with Suppression of Proinflammation and Modification of Gut Microbiome. Nutrition Research 2021, 93, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.Y.; Ekeuku, S.O.; Trias, A. The Role of Geranylgeraniol in Managing Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, Z.W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.H.; Wu, X.Y.; Liu, S.Z.; Bin, Y.L.; Cai, B.P.; Huang, S.Y.; Fang, M.J.; et al. Hinokione: An Abietene Diterpene with Pancreatic β Cells Regeneration and Hypoglycemic Activity, and Other Derivatives with Novel Structures from the Woods of Agathis Dammara. J Nat Med 2024, 78, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gáborová, M.; Šmejkal, K.; Kubínová, R. Abietane Diterpenes of the Genus Plectranthus Sensu Lato. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubelen, A.; Topcu, G.; Johansson, C.B. Norditerpenoids and Diterpenoids from Salvia Multicaulis with Antituberculous Activity. J Nat Prod 1997, 60, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.R.; Chang, W.W.; Chen, S.M. Nerolidol Inhibits Proliferation of Leiomyoma Cells via Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced DNA Damage and Downregulation of the ATM/Akt Pathway. Phytochemistry 2021, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judzentiene, A.; Butkiene, R.; Budiene, J.; Tomi, F.; Casanova, J. Composition of Seed Essential Oils of Rhododendron Tomentosu. Nat Prod Commun. 2012, 227–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.K.; Tan, L.T.H.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H.; Goh, B.H. Nerolidol: A Sesquiterpene Alcohol with Multi-Faceted Pharmacological and Biological Activities. Molecules 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouso, M.R.; Cairrao, E. Effect of Retinoic Acid on the Neurovascular Unit: A Review. Brain Res Bull 2022, 184, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.P.; Casadesus, G.; Zhu, X.; Lee, H.G.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A.; Gustaw-Rothenberg, K.; Lerner, A. All-Trans Retinoic Acid as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Expert Rev Neurother 2009, 9, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Lagos, K.; Benson, M.J.; Noelle, R.J. Retinoic Acid in the Immune System. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008, 1143, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbiai, E.H.; Amina, B.; Kaoutar, A.; Saidi, R.; Lamrani, Z.; Pinto, E.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Maouni, A.; Pinto da Silva, L. Chemical Characterization and Evaluation of Antimicrobial Properties of the Wild Medicinal Mushroom Ganoderma Lucidum Growing in Northern Moroccan Forests. Life 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Yu, L. Effects of Extraction Solvent on Wheat Bran Antioxidant Activity Estimation. LWT—Food Science and Technology 2004, 37, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, B.; Panesar, P.S.; Chopra, H.K.; Gul, K. Characterization of Secondary Metabolites from Various Solvent Extracts of Saffron Floral Waste. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences 2015. [CrossRef]

- Packialakshmi, N.; Naziya, S. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis of Various Solvent Extracts of Caralluma Fimbriyata. 2014, 04, 20–25. 04. [CrossRef]

- Tomsone, L.; Kruma, Z.; Galoburda, R. Comparison of Different Solvents and Extraction Methods for Isolation of Phenolic Compounds from Horseradish Roots. International Scholarly and Scientific Research & Innovation 2012, 6, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, H.; Nguyen, V.; Vuong, Q.; Bowyer, M.; Scarlett, C. Effect of Extraction Solvents and Drying Methods on the Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Helicteres Hirsuta Lour Leaves. Technologies (Basel) 2015, 3, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.D.; Angkawijaya, A.E.; Tran-Nguyen, P.L.; Huynh, L.H.; Soetaredjo, F.E.; Ismadji, S.; Ju, Y.H. Effect of Extraction Solvent on Total Phenol Content, Total Flavonoid Content, and Antioxidant Activity of Limnophila Aromatica. J Food Drug Anal 2014, 22, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avcı, E.; Avcı, G.A.; Kose, D.A. Determination of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Medically Important Mushrooms Using Different Solvents and Chemical Composition via GC / MS Analyses. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2014, 2, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, K.; Mallikarjun, N.; Naika, R.; Venugopal, T.M. Antioxdative Activities of Wild Macro Fungi Ganoderma Applanatum (PERS.) PAT. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research 2014, 7, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Tel, G.; Ozturk, M.; Duru, M.E.; Turkoglu, A. Antioxidant and Anticholinesterase Activities of Five Wild Mushroom Species with Total Bioactive Contents. Pharm Biol 2015, 53, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Homayoonfal, M. Exploring the Anti-Cancer Potential of Ganoderma Lucidum Polysaccharides (GLPs) and Their Versatile Role in Enhancing Drug Delivery Systems: A Multifaceted Approach to Combat Cancer. Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Hashemi, S.A.; Gholami, A.; Omidifar, N.; Chiang, W.H.; Neralla, V.R.; Yousefi, K.; Shokripour, M. Ganoderma Lucidum Methanolic Extract as a Potent Phytoconstituent: Characterization, In-Vitro Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljović, S.; Veljović, M.; Nikićević, N.; Despotović, S.; Radulović, S.; Nikšić, M.; Filipović, L. Chemical Composition, Antiproliferative and Antioxidant Activity of Differently Processed Ganoderma Lucidum Ethanol Extracts. J Food Sci Technol 2017, 54, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronza, M.; Murillo, R.; Ślusarczyk, S.; Adams, M.; Hamburger, M.; Heinzmann, B.; Laufer, S.; Merfort, I. In Vitro Cytotoxic Activity of Abietane Diterpenes from Peltodon Longipes as well as Salvia Miltiorrhiza and Salvia Sahendica. Bioorg Med Chem 2011, 19, 4876–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, P.; Deng, G.; Yuan, W.; Su, Z. Cytotoxic Compounds from Invasive Giant Salvinia (Salvinia Molesta) against Human Tumor Cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2013, 23, 6682–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardwell, G.; Bornman, J.F.; James, A.P.; Black, L.J. A Review of Mushrooms as a Potential Source of Dietary Vitamin D. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Collection month | September–October |

| Location | Chandragiri Hill, Kathmandu, Nepal |

| Elevation | 7482 ft (2280 m) above sea level |

| Coordinates | Latitude: 27.67402° N; Longitude: 85.19874° E |

| Ecosystem type | Solitary |

| Substrate | Wood, stump, log, stick, base of tree, bark |

| Host tree | Quercus lanata |

| Rot type | White-rot |

| Surrounding trees (20 ft radius) | Predominantly hardwoods |

| Basidiocarp size Texture |

7–12 × 11–19 × 1.5 cm Woody to corky |

| Stipe | Sub-sessile to laterally stipitate, 2–3 cm |

| Pileus shape | Reniform |

| Upper surface | Laccate, dark reddish to purplish, yellowish at margins; brittle, soft |

| Margin | Blunt, rounded, brown-white |

| Pore surface | Creamy to milky coffee; ~5 pores/mm |

| Tube layer | 2–9 mm long, white turning brown when brushed or aged |

| Context | 9 mm thick, brown, without horny deposition |

| Cutis type | Thick-walled claviform with diverticula; 35–42 × 6–8.5 µm |

| Hyphal system | Trimitic: Generative (3.3 µm, hyaline, thin-walled, with clamp); Skeletal (5.8–7.5 µm, brown, thick); Binding (5–7.5 µm, brown) |

| Basidiospores | 8.3–10 × 6.6 µm; yellowish-brown |

| Identification authority |

Prof. Mahesh Kumar Adhikari, Dept. of Plant Resources, Kathmandu |

| Extract | Weight of sample before extraction (gm) | Weight obtained after extraction (gm) | % Yield value |

| Water | 10 | 0.229 | 2.29 d |

| Ethanol | 10 | 0.343 | 3.43 b |

| Methanol | 10 | 0.298 | 2.98 c |

| Acetone | 10 | 0.501 | 5.01 a |

| Compound Name | Solvent Extracts (% area) | Compound class | Key pharmacological relevance | Reference | ||

| GEE | GME | GAE | ||||

| 7,22-Ergostadienone | 3.54 | 2.90 | 2.55 | Sterol | Antithrombotic activity with cardiovascular benefit; antidiabetic, anticancer, and neuroprotective effects; Pro-inflammatory properties (activating Toll-like receptors, cytokines, and chemokines) | [51,54,55,56,57] |

| 9(11)-Dehydroergosteryl 3,5-dinitrobenzoate | 2.90 | 3.13 | 2.70 | Sterol conjugate | Anti-inflammatory; antibacterial (MRSA and S. aureus); and cytotoxic properties | [58,59] |

| δ-Tocopherol | 2.13 | 3.91 | 0.75 | Tocopherol | Antioxidant; anti-inflammatory (primarily via inhibiting protein kinase C and reducing eicosanoid production); anticancer (both in vitro and in vivo prostate xenograft models); cvardiovascular and neuroprotective | [60,61] |

| 4-[5-(2-bromophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl]-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-amine | - | - | 0.35 | Synthetic heterocycle | Anticancer (potentially via targeting Topoisomerase II relaxation activity); antibacterial; anti-inflammatory; analgesic properties; antioxidant | [62,63,64,65,66] |

| Ergosta-tetraenone | 3.86 | - | 1.67 | Sterol derivative | Anticancer (via G2/M arrest and apoptosis induction); nephroprotection (mitigation of renal damage in mouse model); anti-inflammatory | [67,68,69] |

| Ergosterol | - | - | 73.99 | Sterol | Vitamin D2 precursor; lipid soluble antioxidant; anticancer effects (cell cycle arrest and modulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway); antimicrobial; antidiabetic; immunomodulatory effects | [70,71,72] |

| Ferruginol | 3.18 | - | - | Abietane diterpene | Anticancer (apoptosis induction in melanoma, prostate, lung, and ovarian cancer cells); neuroprotective (reduces α-synuclein toxicity and restores LTP in Alzheimer’s models); cardioprotective (both invitro and in vivo models); antimicrobial and antiviral | [73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] |

| Geranylgeraniol | 5.26 | - | 0.89 | Diterpenoid alcohol | Anti-inflammatory (NF-κB inhibition; ↓ IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, COX-2); pain relief; bone and muscle support (muscle regeneration and prevents bisphosphonate-related bone damage); antimicrobial activity; hormonal balance; glucose homeostasis | [81,82,83,84] |

| Hinokione | 2.9 | 5.5 | 0.9 | Abietane diterpene | Anticancer; anti-inflammatory; hypoglycemic & β-Cell regenerative properties (promotes β-cell differentiation and improved glycemia in zebrafish); antibacterial; antioxidant | [85,86,87] |

| Nerolidol acetate | - | 1.70 | - | Sesquiterpene ester | Anticancer; anti-inflammatory; neuroprotective; antimicrobial; antifungal; antioxidant | [88,89,90] |

| Retinoic acid | - | - | 0.50 | Retinoid | Acne and photoaging (promotes cell differentiation and skin repair); anti-cancer (induces differentiation of malignant promyelocytes in acute promyeloid leukemia); neuroprotective | [91,92,93] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).