1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is common in children, affecting between 1 to 4% of

children in the United States. If left untreated, OSA may lead to growth retardation, poor school performance, behavioural problems, and mood disturbance (1).

Adenotonsillectomy has been shown to improve mood, learning and behavioural problems in most children affected by OSA. However, depending on other factors, 15 to 33% of children will have residual OSA following adenotonsillectomy. High risk groups for surgical failure include syndromic children, those with craniofacial anomalies, obesity, and those with severe OSA (2).

The diagnosis of OSA is made with polysomnography (PSG) (1,3). However, PSG cannot identify the anatomical site of airway obstruction (4). Drug induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) has been shown to be able to identify the site of anatomical obstruction and therefore can guide surgical intervention (5). DISE was first described by Croft and Pringle in 1991 (6).

A metanalysis published in 2019 assessed the outcomes of airway surgery guided by DISE and CineMRI or CT in children with residual OSA after adenotonsillectomy. Overall, there was a reduction in the apnoea hypopnea index (AHI) of events by 6.5/hr and an improvement of the lowest oxygen desaturation (LSAT) by 3%. The authors concluded that DISE or imaging-directed surgery for OSA results in a significant improvement in AHI and LSAT (7).

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design:

A retrospective case series with chart review was undertaken. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the ethics board of the Children’s and Adolescent Health Service (CAHS) Clinical Governance Unit (Governance Evidence Knowledge Outcomes (GEKO) Quality Activity #46967) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived. The data collection process adhered to ethical guidelines, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity of all individuals involved. The STROBE reporting guideline, accessed online through Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR), was used in manuscript preparation.

2.2. Subjects:

The approach of the institution at which this research was conducted is to only perform DISE in selected patients such as those who fail adenotonsillectomy or those in whom adenotonsillectomy is not expected to be successful. Medical records of 24 children who underwent DISE at Perth Children’s Hospital between 2018 and 2021 were reviewed. Among these, 19 received surgical interventions for OSA where both pre- and postoperative PSGs were performed. It was this group of patients who comprised the study population.

2.3. Polysomnography:

The PSGs were performed in the NATA accredited Sleep Disorders Unit at Perth Children’s Hospital according to unit protocols, American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Australasian Sleep Association/Australasian Sleep Technologists Association recommendations (8–10) and published clinical practice guidelines (11–13) with Compumedics™ Profusion PSG 3 equipment (Compumedics™ Limited, Victoria, Australia). Type 1 PSGs were attended overnight by sleep scientists and measured EEG, EOG, chin and diaphragmatic EMG, airflow with nasal pressure and oro-nasal thermistor, respiratory effort with inductance plethysmography, ECG, pulse oximetry, TCO2, body position, snore volume and time-linked audio-video. Sleep scientists used standard rules (8,9,14) to stage sleep and score respiratory events and reports were generated by paediatric sleep physicians.

The changes in Obstructive Apnoea-Hypopnea Index (OAHI) and oxygen saturation nadir pre and post-surgery were compared.

2.4. Drug Induced Sleep Nasendoscopy:

All DISE procedures were performed at one primary institution by multiple surgeons from the same ENT department. At Perth Children’s Hospital, there is no fixed anaesthetic protocol for this procedure; however, the general guidelines are to avoid any premedication and topical anaesthesia to the larynx, and nasal vasoconstriction should be delayed until after the nasal airway has been adequately assessed. For children who tolerate awake intravenous (IV) cannulation, dexmedetomidine and propofol are used: dexmedetomidine initial loading dose of 0.5–1 µg/kg, followed by infusion of 0.5–1 µg/kg/hr; propofol is administered via Target-Controlled Infusion (TCI) using the Paedfusor model with a target of 2 µg/kg/min. Children who do not tolerate awake IV cannulation are given an induction with Sevoflurane to facilitate IV cannulation. Once IV access is established, cease Sevoflurane and initiate dexmedetomidine and propofol as outlined above. Patients were positioned in a supine position. A 2.8mm flexible endoscope was then passed to assess the turbinates, adenoid, palate, tonsils, oropharynx, tongue base and epiglottis and supraglottis. This was done with and without jaw thrust manoeuvre to assess the difference in airway patency between the two states. Results were recorded using a combination of descriptive methods and the VOTE grading system (15).

2.5. Statistical Analysis:

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise and present our findings. Quantitative data was assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Parametric data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analysed using the student’s t-test. Non-parametric data were presented as median with interquartile range (IQR) and analysed using the Wilcoxon signed rank or Mann-Whitney U test. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 and analyses were performed using R commander (version 4.2.3).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The cohort included 57.9% males (N=11), with ages ranging from 0.8 months to 15.6 years (mean age 7.2 ± 4.5 years). Most patients (84.2%, N=16) had at least one comorbidity, with Trisomy 21 being the most common (N=6). Details of comorbidities are outlined in

Table 1. Three patients were classified as underweight for age and six patients were considered obese (Body Mass Index (BMI) >95

th centile). Fifteen children presented with residual OSA after adenotonsillectomy, and four were surgically naïve. Craniofacial abnormalities were the primary indication for DISE in the surgically naïve group, affecting three patients (one with Robin sequence and cleft palate, one with micrognathia and one with Patau syndrome).

3.2. Surgical Interventions:

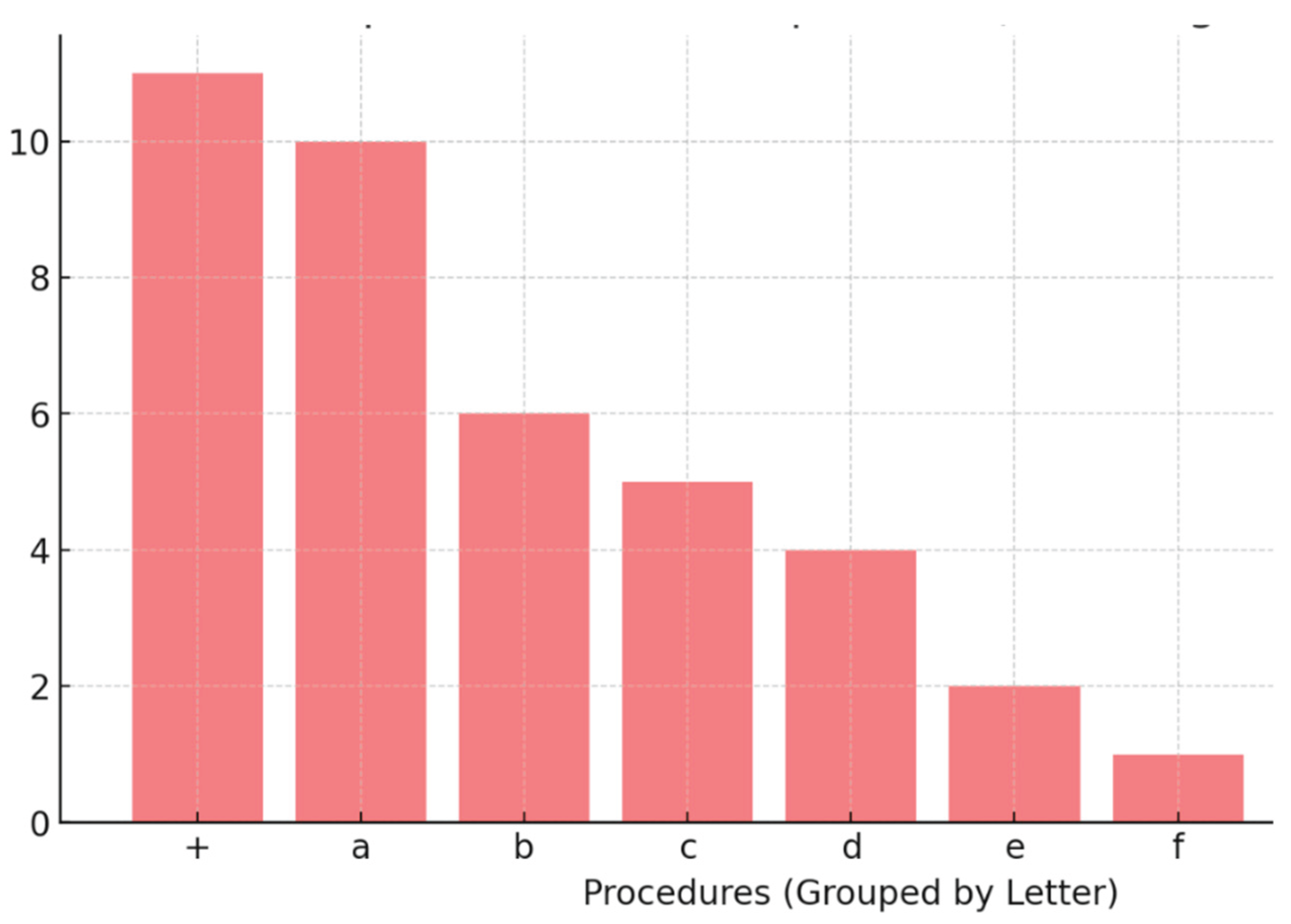

Surgical procedures were based on the DISE findings at the time, with interventions including adenoidectomy (N=10), turbinate reduction (N=6), tongue-base procedures (N=5), tonsillectomy (N=4), supraglottoplasty (N=2), division of nasal adhesions (N=1) and laryngeal type 1 cleft repair (N=1).

Figure 1.

+: Number of patients who had a combination of procedures a-h.

a: Adenoidectomy* (8 revision adenoidectomies)

|

| b: Turbinate surgery* |

| c: TBR* |

| d: Tonsillectomy* |

| e: Supraglottoplasty* |

| f: Division of nasal adhesions* |

| *Number of procedures in total, alone or in combination

|

3.2.1. Adenoidectomy (N=10, 52.6%)

Of the ten patients who underwent adenoidectomy, nine were done in conjunction with other procedures: five with turbinate procedures, three with tonsil surgery and one with tongue base reduction surgery. Two were primary adenoidectomies and eight were revision procedures. Of the primary adenoidectomies, one was done alone in a six-month-old baby who was ex-premature and had micrognathia, and the other was done as part of primary adenotonsillectomy in a 2-year-old child.

3.2.2. Turbinate Reduction (N=6, 31.6%)

Only one patient had turbinoplasty alone, while the other five were performed in conjunction with revision adenoidectomy.

3.2.3. Tongue Base Reduction (N=5, 26.3%)

Most of the tongue base reductions were done in isolation, while one was performed with a revision adenoidectomy.

3.2.4. Tonsil Surgery (N=4, 21.1%)

Three of the four tonsil procedures were performed with revision adenoidectomy and one was in isolation. The tonsillectomy performed without adenoidectomy was in a child with Trisomy 13 and a cleft palate.

3.2.5. Supraglottoplasty (N=2, 10.5%)

One supraglottoplasty was performed in a patient with PRS who also had placement of a nasopharyngeal airway, and the other was performed in conjunction with a repair of type 1 laryngeal cleft in a patient with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome.

3.2.6. Division of Nasal Synechiae (N=1, 5.3%)

This was performed as the sole procedure in an 11 year-old patient with Opitz GBBB syndrome.

3.3. Outcomes:

When analysing the patient study population (N=19), there were no statistically significant changes to pre- and post- intervention OAHI or LSAT following DISE directed surgical intervention.

With sub-group analysis, younger age, higher severity of OSA and the absence of a diagnosis of Trisomy 21 were found to be predictors of surgical success. Obesity was associated with failure of surgical intervention.

Children who had an improvement in their PSG findings post intervention, were significantly younger than those without improvement (5.1 +/- 3.4 years old vs. 10 +/- 4.5 years old) (p<0.02)

Children who had a higher OAHI on pre-operative PSG were also more likely to benefit from DISE directed surgery (median OAHI 10.1/hr for those who saw improvement versus. OAHI 3.9/hr for those who did not,

Table 2.)

There was also statistically significant improvement in median OAHI after DISE-directed surgical intervention in children without Trisomy 21 and in patients who were classified as having severe OSA on pre-operative PSG. (

Table 3 and

Table 4.)

Children with a BMI below the 95

th centile also benefited from surgical intervention as opposed to those above the 95

th centile. In the non-obese group, median pre-operative OAHI was 8.2/hr vs. a post-operative score of 2.6/hr,

Table 5 (P<0.02). In patients with a BMI>95

th there was no improvement in OAHI.

Adenoidectomy (alone or as part of a multilevel approach) was the most commonly performed surgery in the patient cohort (N=10, 52.6%). Of these, eight were revision procedures and two were primary adenoid surgeries. Six out of the 10 adenoidectomies (including both primary procedures) showed improvement in post-operative PSG parameters.

If we assume that post-operative improvement in PSG indicates “success”, tongue-base reduction was the procedure with the highest rate of success, with four out of five children showing improvement in their post-procedural PSGs (80% success vs. 60% for adenoidectomy).

Turbinate surgery was the second most frequent DISE-directed intervention with six children undergoing this procedure. Tonsillectomy was done in four of our patients, and supraglottoplasty in two. All of these procedures resulted in 50% success rate.

Considering most procedures were done as part of a multilevel approach, it cannot be accurately determined which individual procedure or combination of procedures was responsible for the improvement in OAHI.

Division of intranasal adhesions and a type 1 laryngeal cleft repair were each done in one patient, but neither made a difference to the PSG results post-operatively.

4. Discussion

Previous work has examined outcomes of DISE directed surgery in children, however this study has several importance differences. At the institution at which this research was conducted, DISE is primarily reserved for complex patients who have failed initial surgery. As a result, 84.2% of our cohort had multiple comorbidities or syndromic conditions, and 79% had undergone at least one prior procedure for OSA.

In contrast, comorbidity rates in other studies were lower, including 0% (Esteller et al.), 10% (Saniasiaya et al.), 35% (Socarras et al.), and 57.6% (Wootten et al.) (7,16–18). However, He et al. reported a cohort similar to ours, where 98% of patients had comorbidities. Their study found that 55 out of 56 children had at least one comorbidity, with laryngomalacia (36.3%), Trisomy 21 (36.3%), developmental delay (34.5%), reactive airway disease (18.2%), and Robin sequence (9.1%) being the most common. Notably, all patients had prior upper airway surgery (19).

Other studies varied in their patient profiles. Esteller et al. found no comorbidities in their 20-patient cohort, although all had undergone prior surgery (16). In a systematic review by Saniasiaya et al., only 10% of 996 patients had a comorbidity or syndrome (17). Socarras et al. reported a 35% comorbidity rate among 120 DISE patients (7), while Wootten et al. found that 54% of their 26 patients had Down syndrome, with the rest being non-syndromic (18).

A slight male predominance was observed in our study (57.9%), which aligns with findings from He et al. (66%) and Esteller et al. (70%). Other studies showed more balanced distribution of sex, such as Wootten et al. (50% male) and Socarras et al. (53.5% male) (7,16–19).

Outcome Measures and Surgical Success:

Studies assessing DISE-directed surgery use different outcome measures, with pre- and post-operative PSG comparisons being the most common (7,16–21). Rate of a change in surgical plan after DISE is also sometimes quoted (17,20), as are subjective measures such as improvement in snoring using visual analogue scale (16) and symptom burden (18).

Most studies have shown overall improvement in PSG parameters after DISE directed surgery. He et al. found significant improvements in OAHI and LSAT, though only in children without prior adenotonsillectomy (19). Esteller et al. reported a reduction in AHI, with 25% achieving complete resolution of OSA (16). Socarras et al. showed improvement in PSG parameters but no complete resolution of OSA (defined as AHI < 1.0/hr) (7). Sigaard et al. found that 78% of patients improved to mild OSA and 53% were cured, with surgical plans modified in 50.4% of cases (20). Saniasiaya et al. reported that DISE altered surgical decisions in 30% of cases (17). Wootten et al. looked at both subjective and objective outcomes, finding symptom score improvements and patient satisfaction with airflow, though PSG parameters did not reach statistical significance (18).

Our study also did not show statistically significant improvements in post-operative PSG results. This may be due to the small sample size, but also perhaps as a result of the complex nature of our patients. Comorbidities including developmental and craniofacial abnormalities have been shown to be risk factors for surgical failure in children with OSA (22).

A systematic review by Sim et al. found that DISE-directed tongue surgery reduced AHI by 50% and improved LSAT by 3% (21). Our findings support the effectiveness of tongue-base surgery, with 4 out of 5 children (80%) showing PSG improvements postoperatively. This aligns with previous research from our team, where midline posterior glossectomy led to OSA resolution in 67% of patients, with a 100% cure rate in children of normal weight (23).

Comparison of Surgical Procedures:

Like our cohort, He et al. also found that adenoidectomy was the most commonly performed procedure (48% He et al. vs. 52.6% present study). Similar rates were also seen with tonsil surgery (27% vs. 21.1% ), and tongue base surgery (20% vs. 26.3%). Nasal surgery was infrequent in both studies (11% vs. 5.3%). However, supraglottoplasty was more common in He et al.’s study (38%) compared to ours (10.5%) (19).

Other studies differed in surgical distribution. Wootten et al. reported tongue-base surgery as the most common procedure, while Esteller et al. found that tonsillectomy was most frequently performed. However, revision adenoidectomy was common across most studies (16,18).

Factors Influencing Surgical Success:

Our data suggests that age, severity of OSA and a diagnosis of Trisomy 21 influence surgical success. Specifically, younger age and the absence of a diagnosis of Trisomy 21 are positive predictors of success – this is in-keeping with the existing literature (5,24).

However, our finding that children with higher pre-operative OAHI scores were more likely to benefit from DISE directed surgery contrasts with the findings of He et al. who found that children with lower OAHI score benefitted more (19). In their study, patients who benefited from surgery had a pre-operative OAHI of 11.5/hr, while those who did not had an OAHI of 19/hr. Previous studies support this finding, although these were in children undergoing primary adenotonsillectomy (24).

Obesity is a well-established factor in severe OSA and reduced surgical success with adenotonsillectomy alone. In our cohort, patients with a BMI below the 95th percentile were more likely to benefit from DISE-directed surgery. This aligns with findings from Van de Perck et al., who studied primarily surgically naïve patients. They found that 50% of obese children had persistent OSA after DISE-directed adenotonsillectomy, which they attributed to the frequent finding of circumferential airway collapse. They found that these patients responded well to CPAP (25).

Study Limitations:

This study has several limitations:

Retrospective design: We relied on PSG parameters to assess treatment success, without considering clinical or subjective improvements.

Small sample size: Larger studies are needed to draw more definitive conclusions.

Variability in DISE assessments: Multiple surgeons performed DISE, leading to potential differences in interpretation and decision-making.

Lack of standardized grading: No single grading system was used for DISE reporting.

Variability in sedation and technique: While most patients were assessed using dexmedetomidine and propofol in the supine position with and without jaw thrust, this was not strictly protocolised, introducing potential variations.

Despite these limitations, our findings contribute valuable insights into DISE-directed surgery in complex paediatric OSA patients. Future studies with standardised protocols and larger cohorts are needed to further refine surgical decision-making and improve patient outcomes.

5. Conclusion

DISE is a valuable diagnostic tool for identifying anatomical sites of airway obstruction and guiding surgical intervention in paediatric patients with OSA.

Our study demonstrates that DISE-directed surgery can lead to improvements in objective PSG parameters in 1) younger children, 2) those with severe OSA, 3) those with a BMI less than the 95th centile and 4) those without Trisomy 21.

Adenoidectomy and tongue-base reduction showed the most promising outcomes in our cohort, with the latter having the highest success rate based on PSG improvements.

Despite these findings, our study highlights several limitations, including the small sample size, retrospective design, and variability in surgical techniques and DISE interpretation. Future research with larger, prospective studies and standardised protocols for DISE assessments is needed to refine surgical strategies and evaluate the clinical and subjective outcomes of DISE-directed interventions.

In conclusion, DISE serves as an essential adjunct in the management of paediatric OSA, particularly in cases of residual or complex airway obstruction. By identifying site-specific obstructions, it allows for tailored surgical interventions, leading to improved outcomes for appropriately selected patients. However, further research is required to optimise its application and assess its long-term benefits.

Institutional Review Board approval: A retrospective case series with chart review was undertaken. The study was con-ducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the ethics board of the Children’s and Adolescent Health Service (CAHS) Clinical Governance Unit (Governance Evidence Knowledge Outcomes (GEKO) Quality Activity #46967) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

References

- Randel, A. AAO-HNS Guidelines for Tonsillectomy in Children and Adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Sep 1;84(5):566–73.

- Marcus CL, Moore RH, Rosen CL, Giordani B, Garetz SL, Taylor HG, et al. A Randomized Trial of Adenotonsillectomy for Childhood Sleep Apnea. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jun 20;368(25):2366–76.

- Garde AJB, Gibson NA, Samuels MP, Evans HJ. Recent advances in paediatric sleep disordered breathing. Breathe. 2022 Sep;18(3):220151.

- Arganbright JM, Lee JC, Weatherly RA. Pediatric drug-induced sleep endoscopy: An updated review of the literature. World J Otorhinolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2021 Jul;7(3):221–7.

- Akkina SR, Ma CC, Kirkham EM, Horn DL, Chen ML, Parikh SR. Does drug induced sleep endoscopy-directed surgery improve polysomnography measures in children with Down Syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea? Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh). 2018 Nov 2;138(11):1009–13.

- Croft CB, Pringle M. Sleep nasendoscopy: a technique of assessment in snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1991 Oct;16(5):504–9.

- Socarras MA, Landau BP, Durr ML. Diagnostic techniques and surgical outcomes for persistent pediatric obstructive sleep apnea after adenotonsillectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 Jun;121:179–87.

- Iber C, American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events : rules, terminology and technical specifications. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007.

- Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, Gozal D, Iber C, Kapur VK, et al. Rules for Scoring Respiratory Events in Sleep: Update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012 Oct 15;08(05):597–619.

- Pamula, Y. , Campbell, A., Coussens, S., Davey, M., Griffiths, M., Martin, J., Maul, J., Nixon, G., Sayers, R., Teng, A., Thornton, A., Twiss, J., Verginis, N., Waters, K., Whitehead, B., Williams, G., Williamson, B., Wilson, A., and Suresh, S. ASTA/ASA addendum to the AASM guidelines for the recording and scoring of paediatric sleep. Wiley-Blackwell Publ. 2011;20(Supp. 1):4.

- Marcus CL, Brooks LJ, Draper KA, Gozal D, Halbower AC, Jones J, et al. Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics. 2012 Sep;130(3):e714-755.

- Beck SE, Marcus CL. Pediatric Polysomnography. Sleep Med Clin. 2009 Sep;4(3):393–406.

- Kushida CA, Littner MR, Morgenthaler T, Alessi CA, Bailey D, Coleman J, et al. Practice Parameters for the Indications for Polysomnography and Related Procedures: An Update for 2005. Sleep. 2005 Apr;28(4):499–523.

- Kales Anthony, Rechtschaffen Allan, University of California LAngelesBIService, NINDB Neurological Information Network (U.S.). A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Allan Rechtschaffen and Anthony Kales, editors. Bethesda, Md: U. S. National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness, Neurological Information Network; 1968. (National Institutes of Health publication, no. 204).

- Kezirian EJ, Hohenhorst W, De Vries N. Drug-induced sleep endoscopy: the VOTE classification. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011 Aug;268(8):1233–6.

- Esteller E, Villatoro JC, Agüero A, Matiñó E, Lopez R, Aristimuño A, et al. Outcome of drug-induced sleep endoscopy-directed surgery for persistent obstructive sleep apnea after adenotonsillar surgery. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 May;120:118–22.

- Saniasiaya J, Kulasegarah J. Outcome of drug induced sleep endoscopy directed surgery in paediatrics obstructive sleep apnoea: A systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Dec;139:110482.

- Wootten CT, Chinnadurai S, Goudy SL. Beyond adenotonsillectomy: outcomes of sleep endoscopy-directed treatments in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014 Jul;78(7):1158–62.

- He S, Peddireddy NS, Smith DF, Duggins AL, Heubi C, Shott SR, et al. Outcomes of Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy–Directed Surgery for Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2018 Mar;158(3):559–65.

- Sigaard RK, Bertelsen JB, Ovesen T. Does DISE increase the success rate of surgery for obstructive sleep apnea in children? A systematic review of DISE directed treatment of children with OSAS. Am J Otolaryngol. 2023 Nov;44(6):103992.

- Kenneth Sims R, Leeds A, Johnson G, Davide A, Camacho M. Drug Induced Sleep Endoscopy-Directed Tongue Surgery to Treat Persistent Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2025 Jan 27;coa.14283.

- Imanguli M, Ulualp SO. Risk factors for residual obstructive sleep apnea after adenotonsillectomy in children. The Laryngoscope. 2016 Nov;126(11):2624–9.

- Zhen E, Locatelli Smith A, Herbert H, Vijayasekaran S. Midline posterior glossectomy and lingual tonsillectomy in children with refractory obstructive sleep apnoea: factors that influence outcomes. Aust J Otolaryngol. 2022 Sep;5:0–0.

- Bhattacharjee R, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Spruyt K, Mitchell RB, Promchiarak J, Simakajornboon N, et al. Adenotonsillectomy Outcomes in Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Children: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Sep 1;182(5):676–83.

- Van De Perck E, Van Hoorenbeeck K, Verhulst S, Saldien V, Vanderveken OM, Boudewyns A. Effect of body weight on upper airway findings and treatment outcome in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2021 Mar;79:19–28.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).