Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

- -

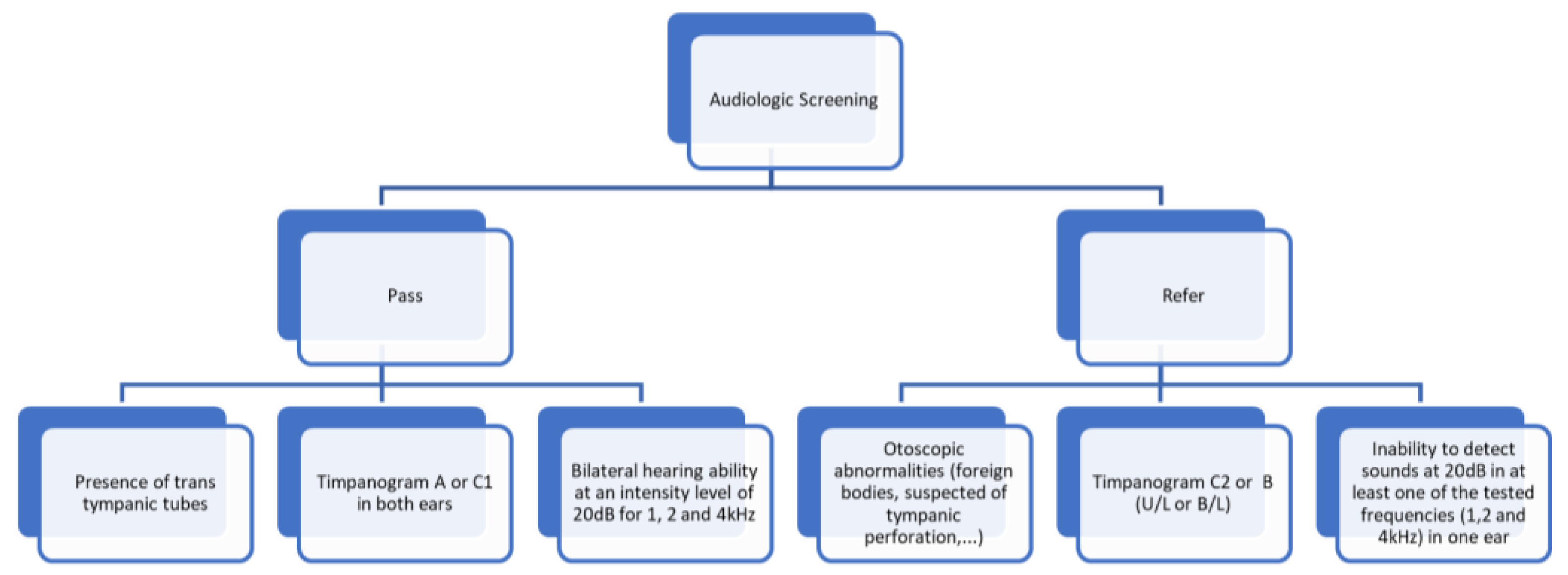

- The presence of trans tympanic tubes, accompanied by a recommendation to continue consulting their Otorhinolaryngologist (ENT).

- -

- A tympanogram results classified as type A or C1 in both ears.

- -

- Bilateral hearing ability at an intensity level of 20dB for frequencies of 1, 2, and 4 kHz.

- -

- Observed alterations during otoscopy, such as the presence of foreign bodies or suspected perforations.

- -

- A tympanogram results classified as type C2 or B in one or both ears.

- -

- Inability to detect sounds at 20dB in at least one of the tested frequencies in one ear.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Screening Results

3.2. Medical Referral

3.3. Association of Medical Otoscopy Findings with Tympanogram Types

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davidse, Neeltje J., et al. Cognitive and Environmental Predictors of Early Literacy Skills. Read Writ. 2011, Vol. 24, pp. 395-412. [CrossRef]

- Rayner, Keith, et al. How Psychological Science Informs the Teaching of Reading. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2001, Vol. 2, pp. 31-74. [CrossRef]

- Hand, E D, Lonigan, C J e Puranik, C S. Prediction of kindergarten and first-grade reading skills: Unique contributions of preschool writing and early-literacy skills. Reading and Writing. 2024, Vol. 37, 1, pp. 25-48. [CrossRef]

- Ehri, Linnea C. Development of Sight Word Reading: Phases and Findings. [ed.] Margaret J. Snowling e Charles Hulme. The Science of Reading: a Handbook. Singapore : Blackwell Publishing, 2007, pp. 135-154.

- Share, D. L. Blueprint for a universal theory of learning to read: The Combinatorial Model. Blueprint for a universal theory of learning to read: The Combinatorial Model. 2025, Vol. 60, 2. [CrossRef]

- Furgoni, A, Martin, C D e Stoehr, A. A cross linguistic study on orthographic influence during auditory word recognition. Sci Rep . 2025, Vol. 15, p. 8374. [CrossRef]

- Boothroyd, Arthur. Speech Perception in the Classroom. [autor do livro] Joseph J. Smaldino e Carol Flexer. Handbook of Acoustic Accessibility - Best Practices for Listening, Learning, and Literacy in the Classroom. New York - Stuttgart : Thieme, 2012, pp. 18-33.

- Klatte, Maria, Wegner, Marlis e Hellbruck, Jurgen. Noise in School Environment and Cognitive Perfomance in Elementary School Children. Part B - Cognitive Psychological Studies. Forum Acusticum 2005. [Online] 2005. [Citação: 15 de Maio de 2010.] http://intellagence.eu.com/acoustic2008/cd1/data/fa2005-budapest/paper/682-0.pdf.

- Gordon, K R e Grieco-Calub, T M. Children build their vocabularies in noisy environments: The necessity of a cross-disciplinary approach to understand word learning. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. Mar-Apr de 2024, Vol. 15, 2, p. e 1671. [CrossRef]

- McFadden, Brittany e Pittman, Andrea. Effect of minimal hearing loss on children’s ability to multitask in quiet and in noise. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. July de 2008, Vol. 39 (3), pp. 342–351. [CrossRef]

- Porter, Heather e Bess, Fred H. Children with Unilateral Hearing Loss. 2011, pp. 175-192.

- Tharpe, Anne Marie. Permanent Minimal and Mild Bilateral Hearing Loss in Children: Implications and Outcomes. [autor do livro] Richard Seewald e Anne Marie Tharpe. Comprehensive Handbook of Pediatric Audiology. University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada : Plural Publishing, Inc., 2011, pp. 193-202.

- World Health Organization. Hearing screening: considerations for implementation. 2021. ISBN 978-92-4-003276-7 (electronic version), ISBN 978-92-4-003277-4 (print version).

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Panel on Audiologic Assessment. Guidelines for Audiologic Screening. Rockville, MD : The Association, 1997.

- Skarżyński, Henryk e Piotrowska, Anna . Screening for Pre-School and School-Age Hearing Problems: European Consensus Statement. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2012, Vol. 76, 1, pp. 120–121. [CrossRef]

- Zielhuis, G. A., Rach, G. H. e Broek, Van P. den. The Occurrence of Otitis Media with Effusion in Dutch Pre-School Children. Clinical Otolaryngology & Allied Sciences. Apr. de 1990, Vol. 15, pp. 147-153. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, R M, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Otitis Media with Effusion (Update). Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2016, Vol. 154, 1 Suppl, pp. S1–S41.

- Vanneste , P e Page , C. Otitis media with effusion in children: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. A review. J Otol. Jun de 2019, Vol. 14, 2, pp. 33-39. [CrossRef]

- Mackey, A R, Persson, A e Uhlén, I. Pre-school hearing screening is necessary to detect childhood hearing loss after the newborn period: a study exploring risk factors, additional disabilities, and referral pathways. International journal of audiology . 2025, Vol. 64, 1, pp. 80-88. [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Audiology. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Childhood Hearing Screening. 2011.

- Hunter, Lisa L e Blankenship, Chelsea M. Middle ear measurement. [autor do livro] Anne Marie Tharpe e Richard Seewald. Comprehensive Handbook of Pediatric Audiology. 2. s.l. : Plural Publishing, 2017, pp. 449-473.

- Dows, M e Northern, J. Hearing in Children. 6. London : Williams&Wilkins, 2014.

- Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Concepts and Principles for Tackling Social Inequities in Health: Levelling Up Part I and Part II. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2006.

- Entidade Reguladora da Saúde. Direito à proteção da saúde – O Serviço Nacional de Saúde – Universalidade. Porto, Portugal : s.n., 2021.

- Furtado, Cláudia e Pereira, João. Equidade e Acesso aos Cuidados de Saúde- Documento de Trabalho. Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública, Universidade Nova de Lisboa : s.n., 2010.

- Coração Delta - Associação de Solidariedade Social. Coração Delta - Associação de Solidariedade Social. Coração Delta - Associação de Solidariedade Social. [Online] 2 de junho de 2025. https://www.coracaodelta.com.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Instituto Nacional de Estatística. [Online] 2 de junho de 2025. https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_main.

- Anwar, K, et al. Otitis media with effusion: Accuracy of tympanometry in detecting fluid in the middle ears of children at myringotomies. Pak J Med Sci. doi: 10.12669/pjms.322.9009, Mar-Apr de 2016, Vol. 32, 2, pp. 466-70. [CrossRef]

- Fiellau-Nikolajsen, M. Tympanometry and middle ear effusion: a cohort-study in three-year-old children. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 1980, Vol. 2, 1, pp. 39-49. [CrossRef]

- Brodie, K D, et al. Outcomes of an Early Childhood Hearing Screening Program in a Low-Income Setting. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2022, Vol. 148, 4, pp. 326–332. [CrossRef]

- Lü, J, et al. Screening for delayed-onset hearing loss in preschool children who previously passed the newborn hearing screening. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2011, Vol. 75, 8, pp. 1045–1049. [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| U/L Tympanogram | 104 | 9,7 |

| U/L Hearing Screening | 9 | 0,8 |

| U/L Tympanogram + Hearing Screening | 24 | 2,2 |

| B/L Tympanogram | 81 | 7,6 |

| B/L Hearing Screening | 3 | 0,3 |

| B/L Tympanogram+Hearing Screening (U/L) | 31 | 2,9 |

| B/L Tympanogram+Hearing Screening (B/L) | 51 | 4,8 |

| B/L Hearing Screening+Tympanogram (U/L) | 7 | 0,7 |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| ENT Consultation | 123 | 56.7 |

| Monitoring | 30 | 13.8 |

| Medication | 20 | 9.2 |

| Discharge | 19 | 8.8 |

| Other Consultation(s) | 16 | 7.4 |

| Wax Removal | 5 | 2.3 |

| Speech Therapy | 4 | 1.8 |

| Total | 217 | 100.0 |

| Medical Otoscopy | Type A (N = 42) | Type C1 (N = 60) | Type C2 (N = 159) | Type B (N = 173) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 36 (86.4%) | 50 (83.3%) | 85 (53.5%) | 33 (19.1%) |

| Otitis Media with Effusion | 2 (4.8%) | 3 (5.0%) | 13 (8.2%) | 91 (52.6%) |

| Acute Otitis Media | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.9%) | 8 (4.6%) |

| Tympanic Depression | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.0%) | 23 (14.5%) | 11 (6.4%) |

| Cerumen | 2 (4.8%) | 2 (3.3%) | 11 (6.9%) | 22 (12.7%) |

| Tympanosclerosis | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Tympanic Perforation | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Eustachian Tube Dysfunction | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (3.3%) | 19 (11.9%) | 7 (4.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).