Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

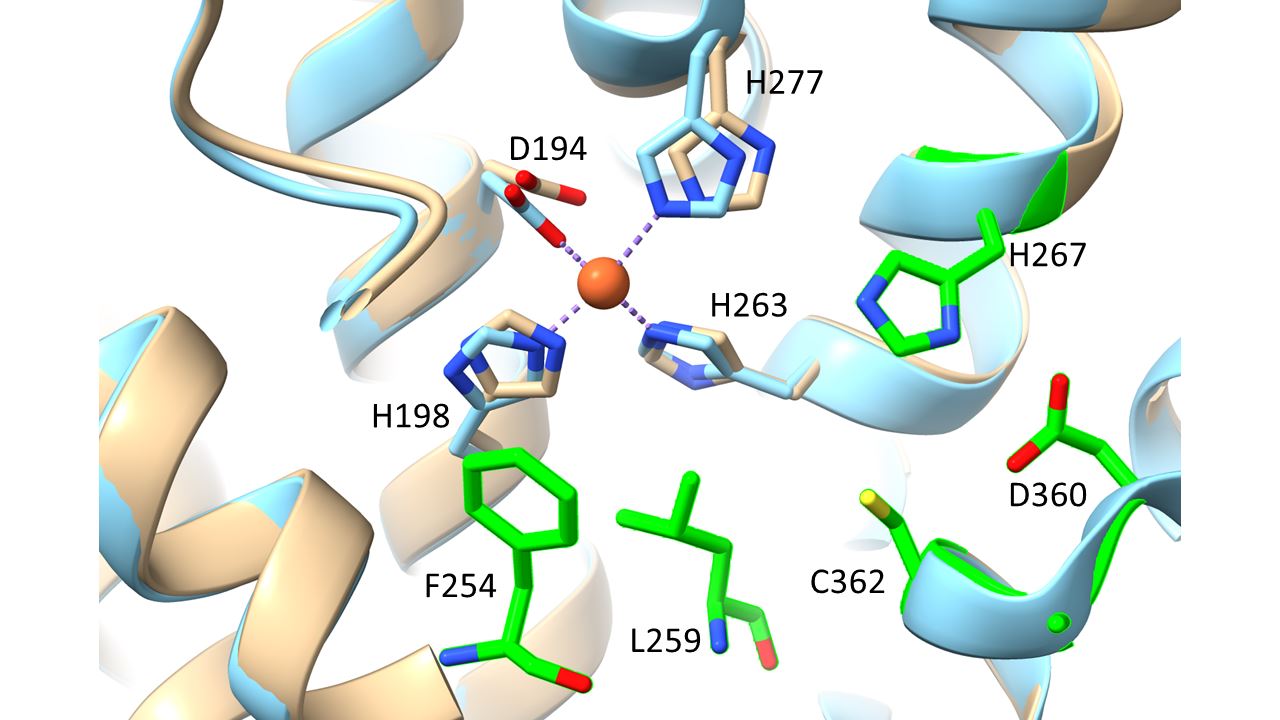

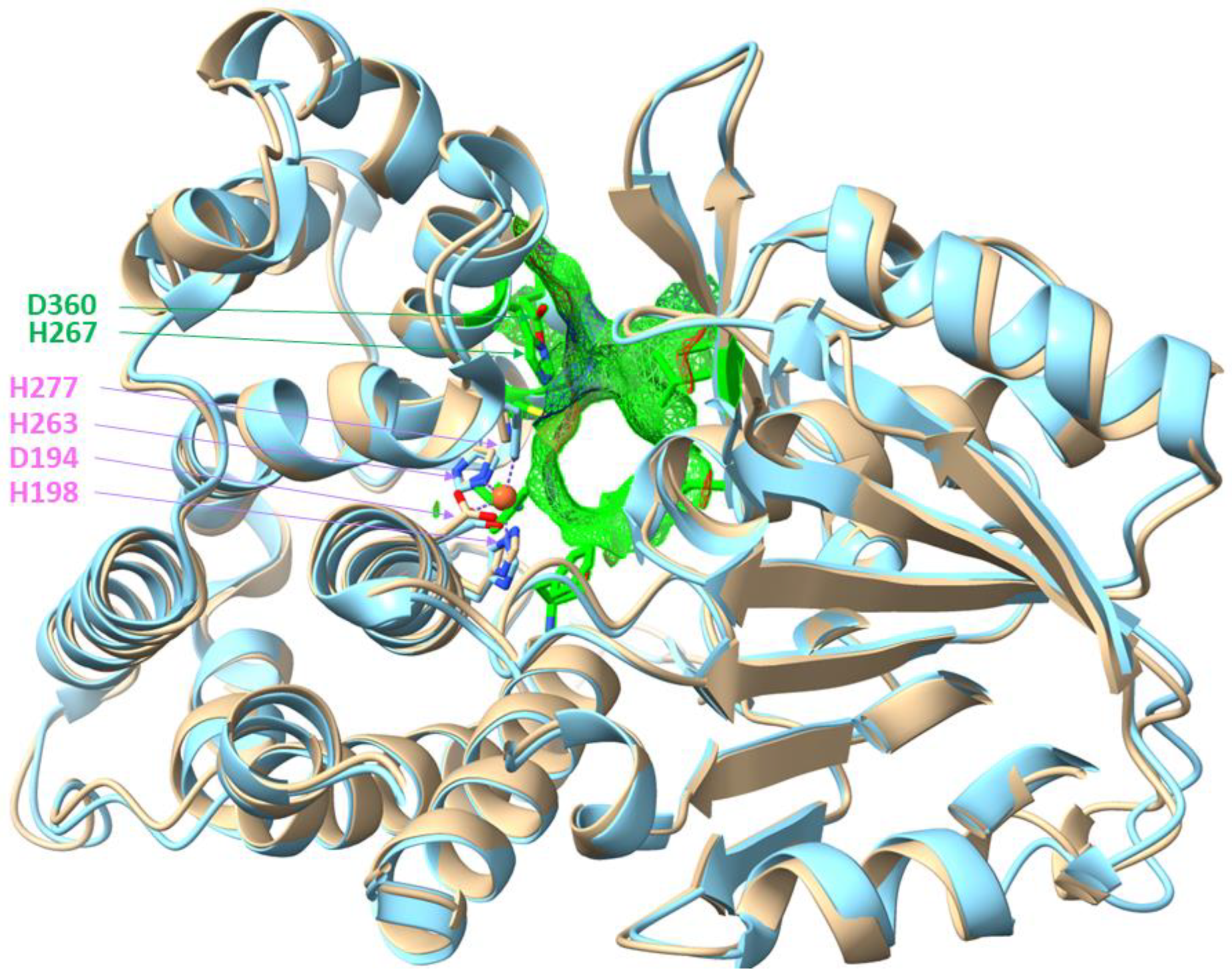

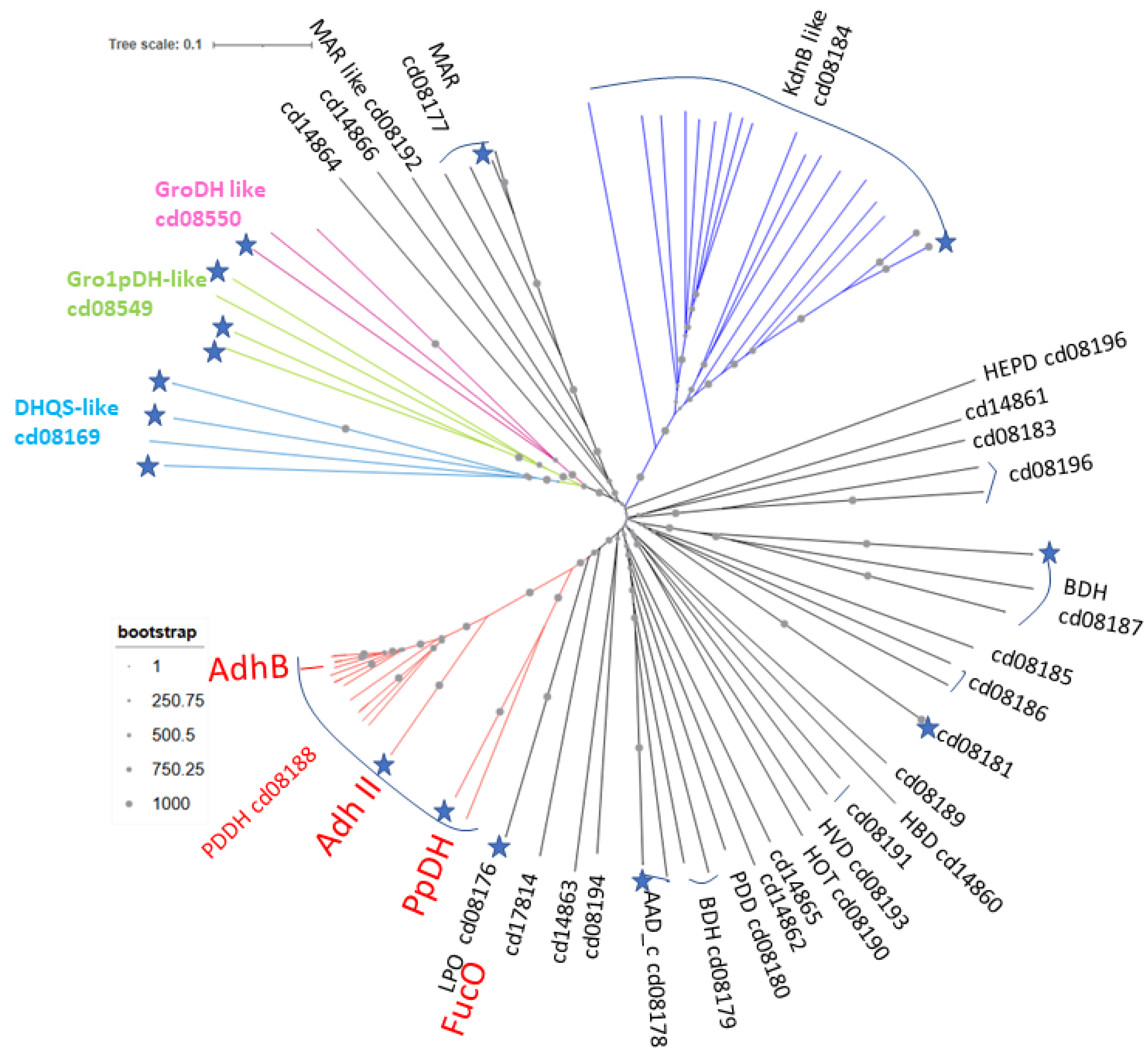

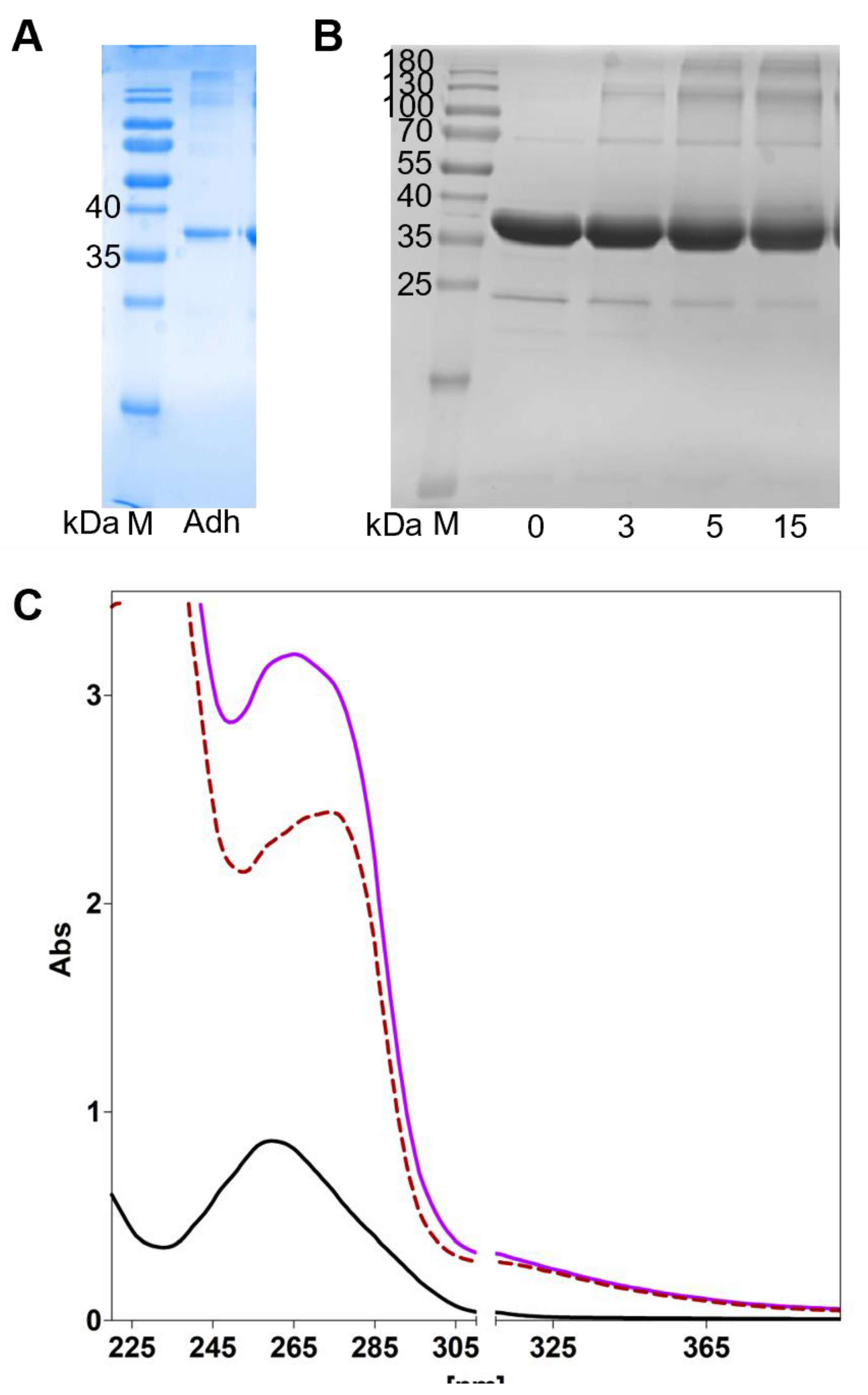

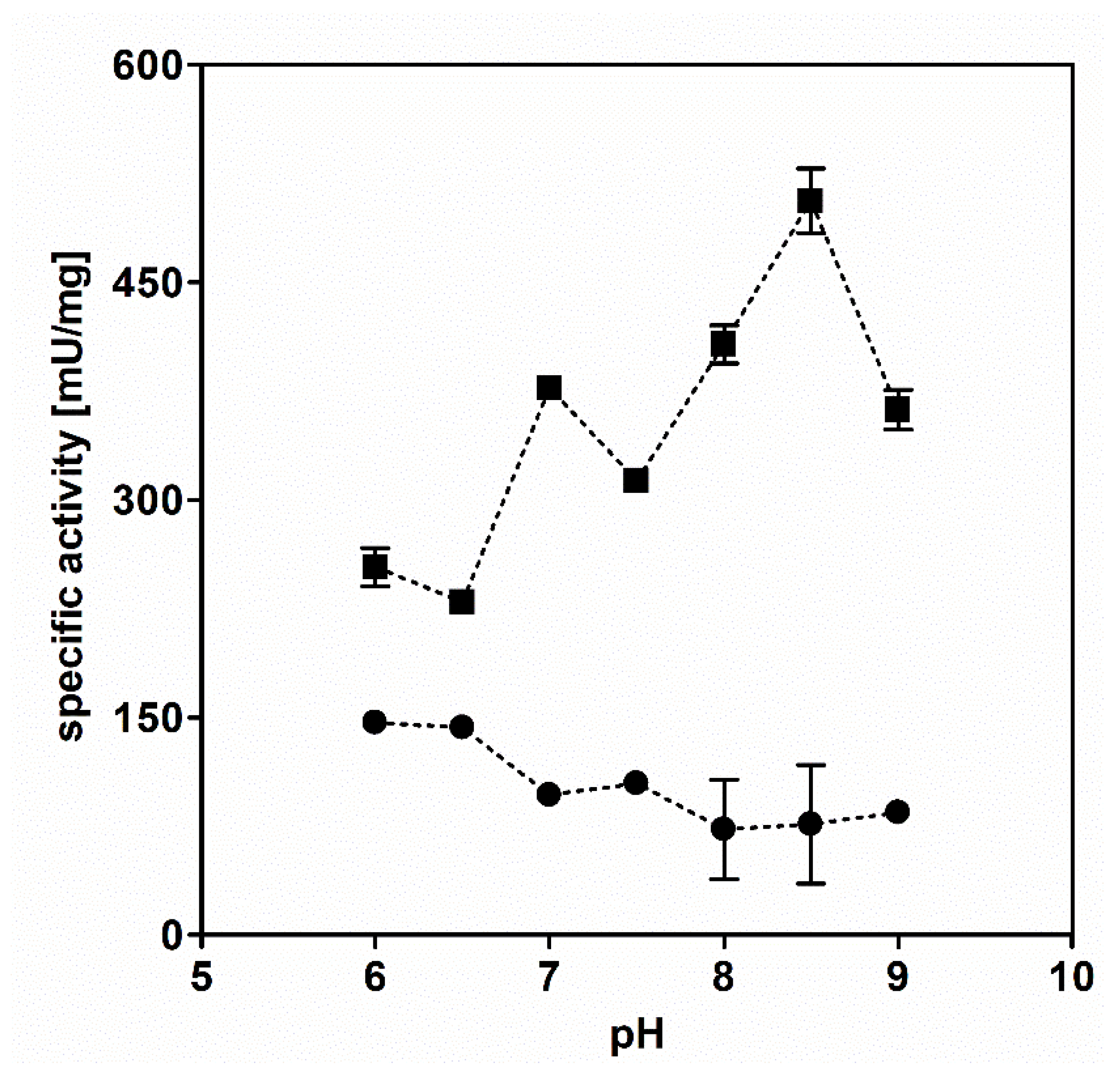

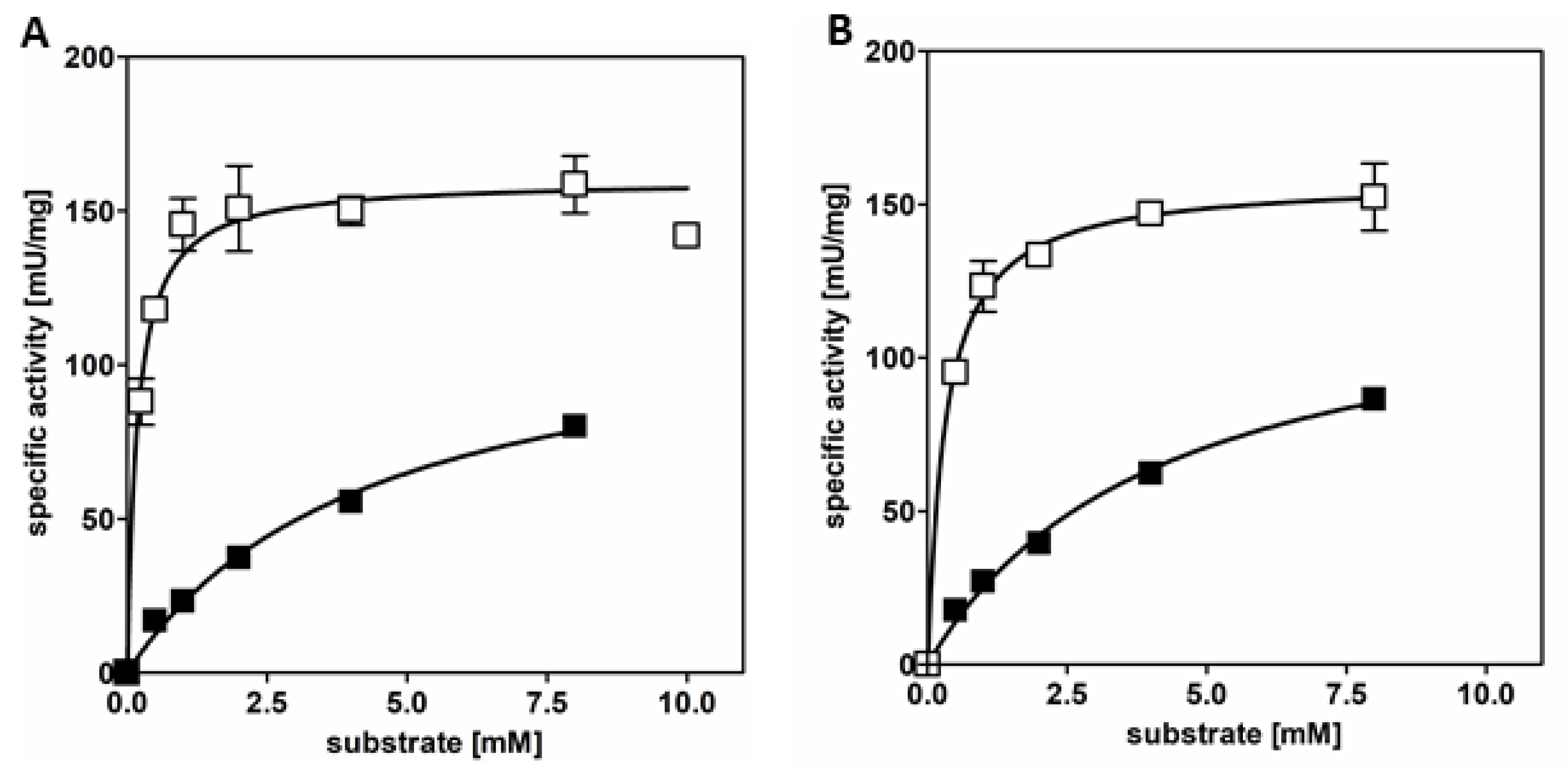

3.1. AdhB Is an Alcohol Dehydrogenase for Small Aliphatic Alcohols

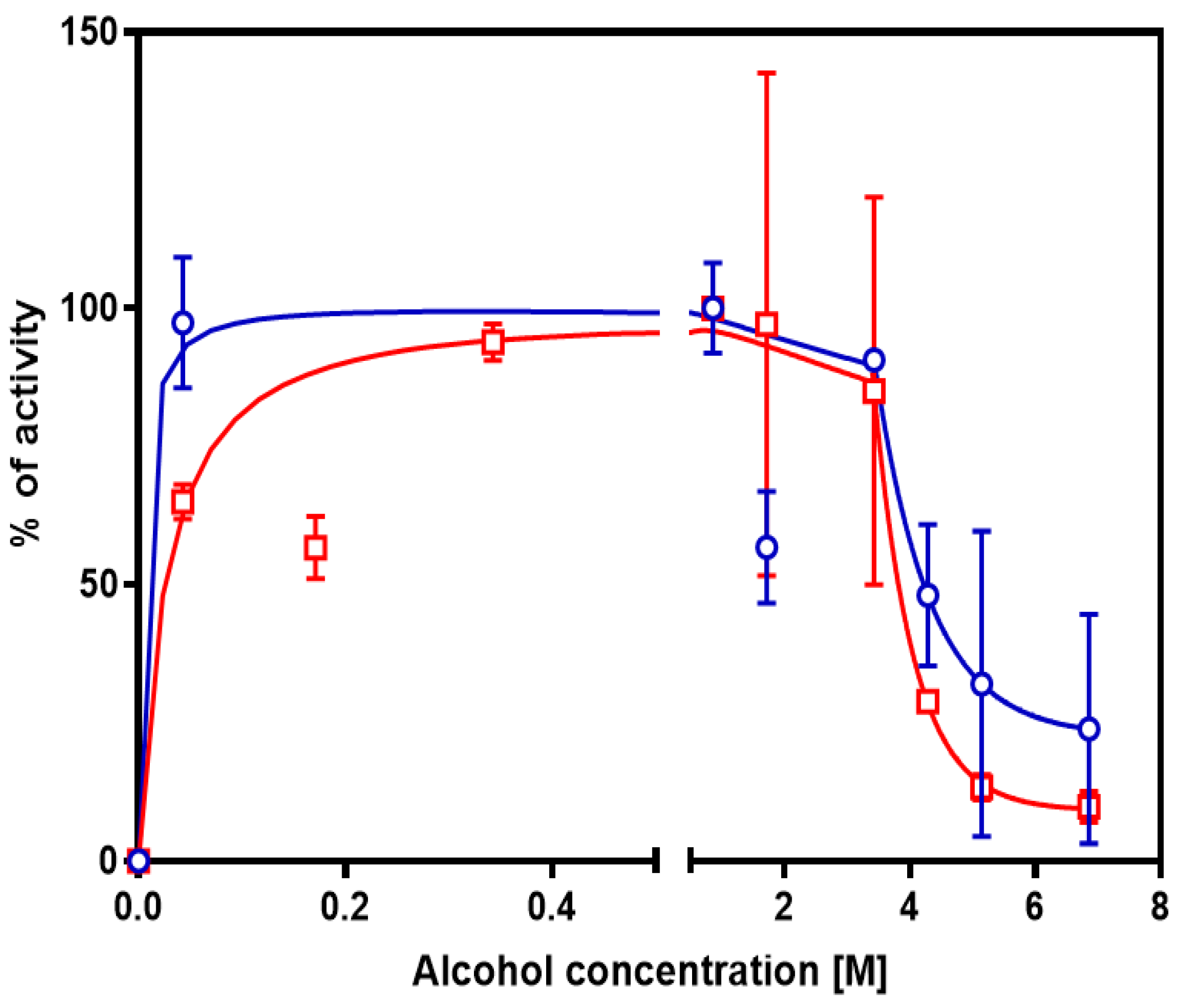

3.2. Tolerance to Alcohols

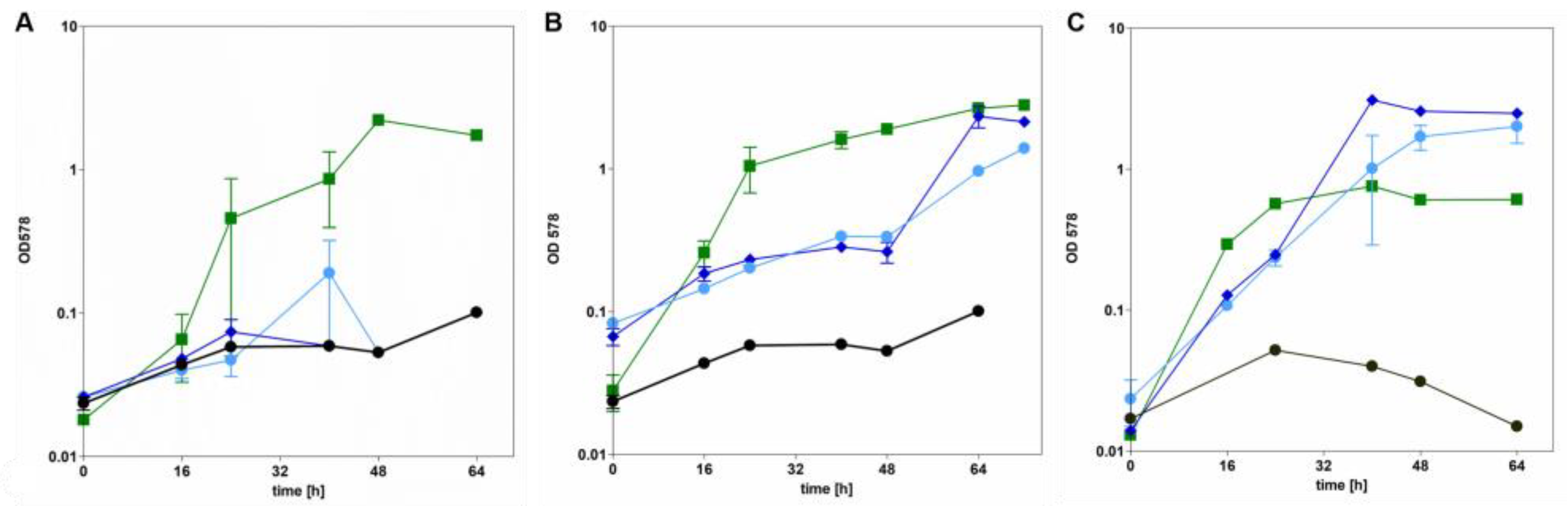

3.3. AdhB Enables Aromatoleum evansii to Grow on Ethanol as Carbon Source

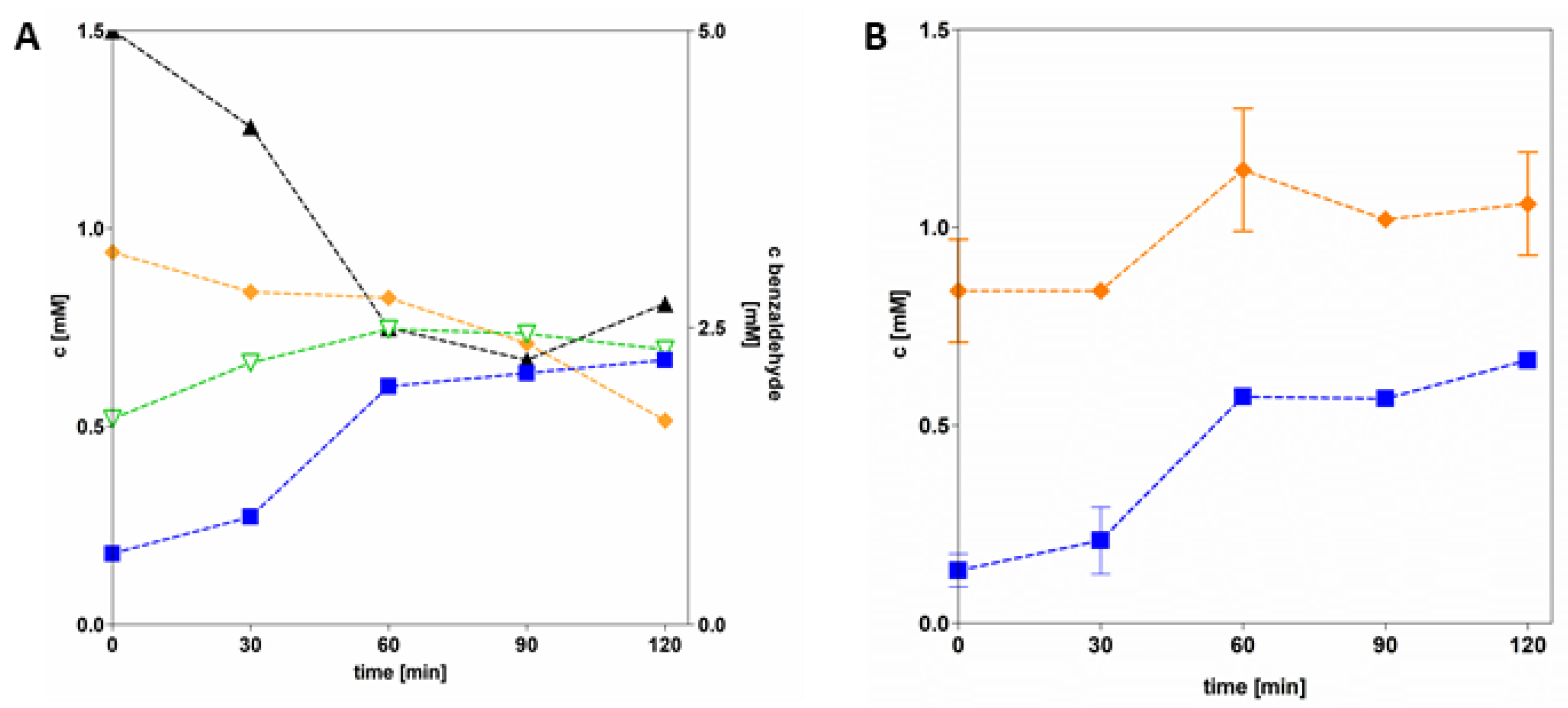

3.4. Application of AdhB in Coupled Enzyme Reactions

4. Discussion

| organism | Growth on ethanol |

adhB gene present (% protein identity) |

| A. aromaticum EbN1 | + | + (100) |

| A. aromaticum pCyN1 | + | + (100) |

| A. bremense PbN1 | - | - |

| A. petrolei ToN1 | + | - |

| Aromatoleum sp. strain EB1 | ND | - |

| A. toluolicum T | + | - |

| A. diolicum 22Lin | - | - |

| A. evansii KB740 | - | - |

| A. buckelii U120 | + | + (99) |

| A. anaerobium LuFRes1 | + | - |

| A. tolulyticum Tol-4 | + | - |

| A. toluvorans Td21 | + | - |

| A. toluclasticum MF63 | ND | - |

| Azoarcus indigens VB32 | ND | - |

| Az. communis SWub3 | + | - |

| Az. olearius BH72 | + | - |

| Thauera aromatica K172/AR-1 | + | + (90) |

| T. chlorobenzoica 3CB1 | ND | + (90) |

| T. aromatica SP/LG356 | ND | + (89) |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| AdhB | Fe-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase from A. aromaticum |

| NAD(P) | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) |

| Pdh | Phenylacetaldehyde dehydrogenase |

| ADH | Alcohol dehydrogenase |

| SDR | Short chain dehydrogenase/reductase |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet-visible light |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecylsulfonate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography-double mass spectrometry |

| Tris | Tris-(hydroxymethyl)aminomethan |

| HEPPS | 4-(Hydroxyethyl)-piperazine-1-propansulfonate |

| AOR | Aldehyde oxidoreductase |

| HPLC | High performance liquid chromatography |

| RID | Refractive index detector |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| TA | Thauera aromatica medium |

| Da | Dalton |

| BaDH | Benzyl alcohol dehydrogenase |

| Vmax | Michaelis-Menten maximum activity |

| Km | Michaelis-Menten constant |

| BV | Benzyl viologen |

| FAD | Flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| DHQS | Dehydroquinate synthase |

| Gro1pDH | Glycerol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GroDH | Glycerol- dehydrogenase |

References

- Rabus, R.; Kube, M.; Heider, J.; Beck, A.; Heitmann, K.; Widdel, F.; Reinhardt, R. The Genome Sequence of an Anaerobic Aromatic-Degrading Denitrifying Bacterium, Strain EbN1. Archives of Microbiology 2005, 183, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, P.; Wünsch, D.; Wöhlbrand, L.; Neumann-Schaal, M.; Schomburg, D.; Rabus, R. The Catabolic Network of Aromatoleum Aromaticum EbN1T. Microbial physiology 2024, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Rabus, R. Functional Genomics of an Anaerobic Aromatic-Degrading Denitrifying Bacterium, Strain EbN1. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2005, 68, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, G.; Arndt, F.; Kahnt, J.; Heider, J. Adaptations to a Loss-of-Function Mutation in the Betaproteobacterium Aromatoleum Aromaticum: Recruitment of Alternative Enzymes for Anaerobic Phenylalanine Degradation. Journal of Bacteriology 2017, 199, e00383–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hege, D.; Gemmecker, Y.; Schall, I.; Oppong-Nti, P.; Schmitt, G.; Heider, J. Single Amino Acid Exchanges Affect the Substrate Preference of an Acetaldehyde Dehydrogenase. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2025, 109, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heider, J.; Hege, D. The Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Superfamilies: Correlations and Deviations in Structure and Function. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2025, 109, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, T.; Sewell, G.W.; Osman, Y.A.; Ingram, L.O. Cloning and Sequencing of the Alcohol Dehydrogenase II Gene from Zymomonas Mobilis. Journal of Bacteriology 1987, 169, 2591–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, L.O.; Conway, T.; Clark, D.P.; Sewell, G.W.; Preston, J.F. Genetic Engineering of Ethanol Production in Escherichia Coli. Applied and environmental microbiology 1987, 53, 2420–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.F.; Fewson, C.A. Molecular Characterization of Microbial Alcohol Dehydrogenases. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 1994, 20, 13–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Tobías, A.; Julián-Sánchez, A.; Piña, E.; Riveros-Rosas, H. Natural Alcohol Exposure: Is Ethanol the Main Substrate for Alcohol Dehydrogenases in Animals? In Proceedings of the Chemico-Biological Interactions; 2011; Vol. 191, pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gaona-López, C.; Julián-Sánchez, A.; Riveros-Rosas, H. Diversity and Evolutionary Analysis of Iron-Containing (Type-III) Alcohol Dehydrogenases in Eukaryotes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmecker, Y.; Winiarska, A.; Hege, D.; Kahnt, J.; Seubert, A.; Szaleniec, M.; Heider, J. A PH-Dependent Shift of Redox Cofactor Specificity in a Benzyl Alcohol Dehydrogenase of <i>Aromatoleum Aromaticum<i> EbN1. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2024, 108, s00253–024. [Google Scholar]

- Coligan, J.E. , Dunn, B.M., Ploegh, H.L., Speicher, D.W., Wingfield, P.T. Current Protocols in Protein Science; Coligan, J.E., Dunn, B.M., Ploegh, H.L., Speicher, D.W., Wingfield, P.T., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, F.; Schmitt, G.; Winiarska, A.; Saft, M.; Seubert, A.; Kahnt, J.; Heider, J. Characterization of an Aldehyde Oxidoreductase from the Mesophilic Bacterium Aromatoleum Aromaticum EbN1, a Member of a New Subfamily of Tungsten-Containing Enzymes. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Analytical Biochemistry 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarska, A.; Hege, D.; Gemmecker, Y.; Kryściak-Czerwenka, J.; Seubert, A.; Heider, J.; Szaleniec, M. Tungsten Enzyme Using Hydrogen as an Electron Donor to Reduce Carboxylic Acids and NAD+. ACS Catalysis 2022, 12, 8707–8717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salii, I.; Szaleniec, M.; Zein, A.A.; Seyhan, D.; Sekuła, A.; Schühle, K.; Kaplieva-Dudek, I.; Linne, U.; Meckenstock, R.U.; Heider, J. Determinants for Substrate Recognition in the Glycyl Radical Enzyme Benzylsuccinate Synthase Revealed by Targeted Mutagenesis. ACS Catalysis 2021, 11, 3361–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hege, D.; Gemmecker, Y.; Clermont, L.; Aleksic, I.; Olesky, G.; Szaleniec, M.; Heider, J. Genetic Manipulation of the Betaproteobacterial Genera Thauera and Aromatoleum. Methods in Enzymology 2025, 714, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, F.; Sun, S.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, T.; Xu, X.; Li, B.; Tan, G. Escherichia Coli Alcohol Dehydrogenase YahK Is a Protein That Binds Both Iron and Zinc. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabus, R.; Wöhlbrand, L.; Thies, D.; Meyer, M.; Reinhold-Hurek, B.; Kampfer, P. Aromatoleum Gen. Nov., a Novel Genus Accommodating the Phylogenetic Lineage Including Azoarcus Evansii and Related Species, and Proposal of Aromatoleum Aromaticum Sp. Nov., Aromatoleum Petrolei Sp. Nov., Aromatoleum Bremense Sp. Nov., Aromatoleum Toluolicum Sp. Nov. and Aromatoleum Diolicum Sp. Nov. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2019, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, H.J.; Kaetzke, A.; Kampfer, P.; Ludwig, W.; Fuchs, G. Taxonomic Position of Aromatic-Degrading Denitrifying Pseudomonad Strains K 172 and KB 740 and Their Description as New Members of the Genera Thauera, as Thauera Aromatica Sp. Nov., and Azoarcus, as Azoarcus Evansii Sp. Nov., Respectively, Members of The. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology 1995, 45, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabus, R.; Wöhlbrand, L.; Thies, D.; Meyer, M.; Reinhold-Hurek, B.; Kampfer, P. Aromatoleum Gen. Nov., a Novel Genus Accommodating the Phylogenetic Lineage Including Azoarcus Evansii and Related Species, and Proposal of Aromatoleum Aromaticum Sp. Nov., Aromatoleum Petrolei Sp. Nov.,<i> Aromatoleum Bremense. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2019, 69, 982–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabus, R.; Widdel, F. Anaerobic Degradation of Ethylbenzene and Other Aromatic Hydrocarbons by New Denitrifying Bacteria. Archives of Microbiology 1995, 163, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabus, R.; Widdel, F. Utilization of Alkylbenzenes during Anaerobic Growth of Pure Cultures of Denitrifying Bacteria on Crude Oil. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1996, 62, 1238–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szaleniec, M.; Heider, J. Obligately Tungsten-Dependent Enzymes─Catalytic Mechanisms, Models and Applications. Biochemistry 2025, 64, 2154–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Song, J.M.; Park, M.Y.; Park, H.M.; Sun, J.; Park, J.H.; Kim, B.Y.; Kim, J.S. Structures of Iron-Dependent Alcohol Dehydrogenase 2 from Zymomonas Mobilis ZM4 with and without NAD+ Cofactor. Journal of Molecular Biology 2011, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montella, C.; Bellsolell, L.; Pérez-Luque, R.; Badía, J.; Baldoma, L.; Coll, M.; Aguilar, J. Crystal Structure of an Iron-Dependent Group III Dehydrogenase That Interconverts L-Lactaldehyde and L-1,2-Propanediol in Escherichia Coli. Journal of Bacteriology 2005, 187, 4957–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçal, D.; Rêgo, A.T.; Carrondo, M.A.; Enguita, F.J. 1,3-Propanediol Dehydrogenase from Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Decameric Quaternary Structure and Possible Subunit Cooperativity. Journal of Bacteriology 2009, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mullan, P.J.; Buchholz, S.E.; Chase, T.; Eveleigh, D.E. Roles of Alcohol Dehydrogenases of Zymomonas Mobilis (ZADH): Characterization of a ZADH-2-Negative Mutant. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 1995, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiten, A.; Kalvelage, K.; Becker, P.; Reinhardt, R.; Hurek, T.; Reinhold-Hurek, B.; Rabus, R. Complete Genomes of the Anaerobic Degradation Specialists Aromatoleum Petrolei ToN1Tand Aromatoleum Bremense PbN1T. Microbial Physiology 2021, 31, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Adam, D.; Giaveri, S.; Barthel, S.; Cestellos-Blanco, S.; Hege, D.; Paczia, N.; Castañeda-Losada, L.; Klose, M.; Arndt, F.; et al. ATP Production from Electricity with a New-to-Nature Electrobiological Module. Joule 2023, 7, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.; Strobl, G.; Feicht, R.; Simon, H. Carboxylic Acid Reductase: A New Tungsten Enzyme Catalyses the Reduction of Non-activated Carboxylic Acids to Aldehydes. European Journal of Biochemistry 1989, 184, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, J.; Ma, K.; Adams, M.W.W. Purification, Characterization, and Metabolic Function of Tungsten- Containing Aldehyde Ferredoxin Oxidoreductase from the Hyperthermophilic and Proteolytic Archaeon Thermococcus Strain ES-1. Journal of Bacteriology 1995, 177, 4757–4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winiarska, A.; Ramírez-Amador, F.; Hege, D.; Gemmecker, Y.; Prinz, S.; Hochberg, G.; Heider, J.; Szaleniec, M.; Schuller, J.M. A Bacterial Tungsten-Containing Aldehyde Oxidoreductase Forms an Enzymatic Decorated Protein Nanowire. Science Advances 2023, 9, eadg668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckel, W.; Thauer, R.K. Energy Conservation via Electron Bifurcating Ferredoxin Reduction and Proton/Na+ Translocating Ferredoxin Oxidation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Bioenergetics 2013, 1827, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubev, G.S.; Borisov, I.L.; Volkov, V. V. Thermopervaporative Removal of Isopropanol and Butanol from Aqueous Media Using Membranes Based on Hydrophobic Polysiloxanes. Petroleum Chemistry 2018, 58, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhiri, A.; Darwish, N.; Hilal, N. Membrane Distillation: A Comprehensive Review. Desalination 2012, 287, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalygin, M.G.; Kozlova, A.A.; Heider, J.; Sapegin, D.A.; Netrusov, A.A.; Teplyakov, V. V. Polymeric Membranes for Vapor-Phase Concentrating Volatile Organic Products from Biomass Processing. Membranes and Membrane Technologies 2023, 5, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarise, A.; Sridhar, S.; Kiema, T.R.; Wierenga, R.K.; Widersten, M. Structures of Lactaldehyde Reductase, FucO, Link Enzyme Activity to Hydrogen Bond Networks and Conformational Dynamics. FEBS Journal 2023, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extance, J.; Crennell, S.J.; Eley, K.; Cripps, R.; Hough, D.W.; Danson, M.J. Structure of a Bifunctional Alcohol Dehydrogenase Involved in Bioethanol Generation in Geobacillus Thermoglucosidasius. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography 2013, 69, 2104–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, S.; Kakizono, T.; Kadota, K.; Das, K.; Taguchi, H. Purification of Two Alcohol Dehydrogenases from Zymomonas Mobilis and Their Properties. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 1985, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Shu, L.; Lu, X.; Wang, Q.; Tišma, M.; Zhu, C.; Shi, J.; Baganz, F.; Lye, G.J.; Hao, J. 1,2-Propanediol Production from Glycerol via an Endogenous Pathway of Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| desalted AdhB | |

| Mg | 0.01 |

| P | 1.88 |

| Ca | 0.03 |

| Mn | 0.02 |

| Fe | 0.10 |

| Co | 0.00 |

| Ni | 0.06 |

| Cu | 0.01 |

| Zn | 0.13 |

| Se | 0.00 |

| Mo | 0.00 |

| W | 0.00 |

| substrate | ethanol | acetaldehyde | n-propanol | propionaldehyde |

| App. Vmax [U/mg] | 121.3 | 160.1 | 129.8 | 158.1 |

| app. kcat [s-1] | 79.7 | 105.1 | 85.2 | 103.8 |

| app.Km [mM] | 4.4 | 0.2 | 4.2 | 0.3 |

| kcat/Km [mM-1 s-1] | 18.1 | 525.5 | 20.3 | 346.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).