1. Introduction

Women in Bangladesh face persistent challenges related to gender-based violence, workplace harassment, and limited access to justice. According to a report by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), nearly 72.6% of women experience some form of violence in their lifetime, including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse [

1]. Despite the existence of legal frameworks aimed at protecting women’s rights, such as the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act 2010 and the Dowry Prohibition Act 2018, many women are either unaware of these protections or unable to access justice mechanisms due to structural, social, or informational barriers [

2]. In recent years, the problem has been exacerbated by the increasing incidence of digital harassment, leading to the enactment of the Cyber Security Ordinance 2025. However, navigating the legal and procedural landscape remains difficult for most women, particularly those in low-literacy or technologically weak environments [

3]. A critical barrier is the unavailability of simple, localized, and accessible legal information, which is a challenge even for educated people. Because legal documents are usually written in complex and formal language, making them hard to interpret without professional legal assistance. Moreover, resources are fragmented across various NGO websites, legal portals, and government databases [

4]. This lack of cohesive, user-friendly, and real-time legal guidance contributes to underreporting of abuse and limited legal redress. Therefore, providing context-aware, conversational access to reliable legal information can be transformative for women. It has the potential to empower them with knowledge, increase reporting, and direct them toward appropriate support services. This paper proposes a chat assistant specifically designed to address this gap using Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) techniques to ensure accurate, real-time, and explainable guidance for users.

Legal frameworks play a pivotal role in safeguarding women’s rights and addressing various forms of abuse and discrimination. In Bangladesh, several important laws exist to protect women, as mentioned before. Additionally, the High Court Directive of 2009 serves as a key policy guideline for preventing sexual harassment in educational institutions and workplaces [

5]. Despite these provisions, a significant gap exists between legislation and its practical application, primarily due to a lack of awareness and understanding among the population, particularly women. Studies have shown that a majority of women do not know where to seek help when their rights are violated, nor do they fully comprehend the protections afforded to them under existing laws [

6]. The complexity of legal language and procedures further alienates victims from pursuing justice. Legal documents are often not translated into accessible formats or local dialects, and many legal aid organizations lack the capacity to provide immediate, understandable guidance [

4]. As a result, women often rely on hearsay, personal belief, or intermediaries, which may expose them to misinformation or exploitation [

7]. Ensuring access to clear, trustworthy, and timely legal information is thus critical. It not only empowers women to recognize abuse and assert their rights, but also promotes better accountability within institutions tasked with protecting them. Integrating such legal knowledge into conversational platforms could bridge the awareness gap and provide a scalable, culturally appropriate support mechanism for Bangladeshi women.

Although Bangladesh has a well-defined set of laws aimed at protecting women, these legal resources are often fragmented across various platforms and institutions. Official legal texts are primarily published through government gazettes, legal databases, or judiciary websites, but these are typically difficult to navigate and not designed for the general public [

8]. In many cases, updates to laws or relevant guidelines are delayed in publication or are not communicated effectively to the community [

7]. Furthermore, most legal information is written in highly technical Bengali or in English, rendering it inaccessible to large portions of the population, especially women in rural areas, who may have limited literacy or digital access [

9]. Legal aid services provided by NGOs and government bodies such as the National Legal Aid Services Organization (NLASO) are valuable, but their capacity to deliver personalized, on-demand legal advice remains limited [

10]. In addition, support services such as helplines, shelters, and legal aid centers often operate independently, with little data interoperability or centralized information systems. As a result, a woman seeking help may not know which service to contact, whether the offender is legally innocent, or what her legal options are. This institutional disconnect creates confusion, delays, and often discourages victims from pursuing justice [

2]. The absence of an integrated, user-friendly platform for accessing legal information and protection mechanisms is a significant bottleneck in ensuring timely and effective support for women. This fragmented ecosystem makes it difficult to build trust in legal remedies and reinforces the marginalization of women within the justice system.

In recent years, chatbots and virtual assistants have become increasingly prevalent across various sectors such as healthcare, finance, and education, providing users with convenient, on-demand access to information and services [

11,

12]. These AI-driven conversational interfaces enable personalized interactions that can improve user engagement and accessibility, often bridging gaps where human resources are limited or overwhelmed. Despite these advances, the application of such technologies in providing legal aid, especially for women, remains significantly underdeveloped. Women often face unique legal challenges related to rights, safety, and social justice, which require not only accurate legal knowledge but also sensitivity to cultural and local contexts [

13]. Legal assistance systems that are localized, culturally aware, and legally informed hold tremendous potential to empower women by delivering relevant, trustworthy guidance tailored to their specific environments [

14]. Thus, integrating AI with conversational interfaces tailored for women’s legal rights can address critical accessibility issues. Such systems can provide scalable, confidential, and user-friendly support, helping overcome barriers posed by fragmented legal information and socio-cultural constraints [

15].

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) represents a transformative approach that combines the strengths of conversational AI with the precision of trusted document retrieval [

16]. By integrating real-time access to external knowledge sources during generation, RAG enables conversational agents to produce responses that are not only fluent and coherent but also firmly grounded in authentic, up-to-date documents. This capability is especially crucial in legal domains, where accuracy and traceability are paramount. Traditional large language models (LLMs) may suffer from hallucination, that generates plausible but incorrect or unverifiable information [

17]. RAG addresses this challenge by anchoring generated answers in relevant legal texts, such as statutes, regulations, NGO helpline details, and case precedents, thereby improving reliability and user trust [

18]. Moreover, by dynamically retrieving pertinent documents from a curated legal corpus, RAG bridges the knowledge gap between static model training data and evolving real-world legal information. This ensures that users receive contextual, timely, and relevant legal guidance tailored to their queries [

19]. In the context of women’s legal assistance, such real-time, document-backed conversational AI can empower users with actionable insights while minimizing misinformation risks.

Research Objectives

The primary goals of this research are outlined as follows:

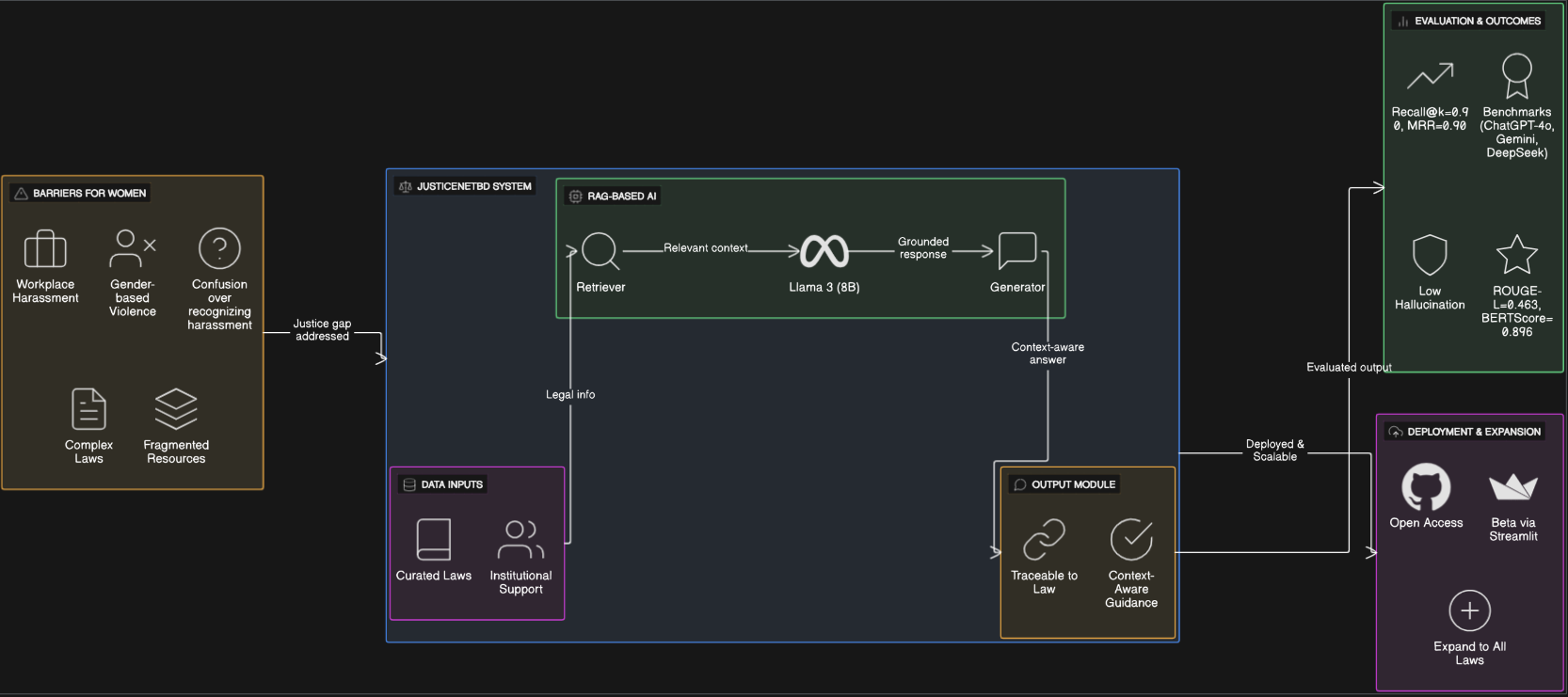

To experimentally develop a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)-based Legal Assistant system named JusticeNetBD focused on providing accessible and accurate legal aid tailored specifically for women.

-

To support legal queries in simple English language during the initial implementation phase, using a curated corpus derived from authoritative Bangladeshi legal sources, including:

- –

The Bangladesh Penal Code, 1860

- –

The Women and Children Repression Prevention Act, 2000

- –

The Dowry Prohibition Act, 2018

- –

Other relevant acts

To ensure contextually grounded responses by integrating these legal documents into a retrieval system that feeds into a generative language model.

-

To rigorously evaluate the assistant’s performance using quantitative metrics such as:

- –

Recall@k and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR)

- –

ROUGE-L

- –

BERTScore F1

To benchmark the assistant’s performance against contemporary state-of-the-art and commercial models such as ChatGPT-4o Turbo, Gemini Flash 2.5 and DeepSeek-V3 using response generation metrics and statistical hypothesis testing, thereby assessing its comparative effectiveness in the domain of legal conversational AI.

3. Methodology

This section outlines the design and development process of the proposed women’s rights and safety chat assistant. The methodology follows a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) architecture to combine generative language modeling with trustworthy legal and institutional knowledge sources. The system comprises three core stages: (i) corpus generation and preprocessing, (ii) LLM selection and fine-tuning for generation, and (iii) end-to-end RAG workflow integration. Below, each component is described in detail, beginning with the data corpus creation. Reproducibility and model guidelines are available in the GitHub repository [

35].

3.1. Corpus Construction from Legal and Institutional Sources

To ensure accurate and explainable responses, a high-quality knowledge corpus composed of legally verified documents and public service datasets is curated. These sources were selected to reflect the laws, protection mechanisms, and real-world support systems available to women in Bangladesh. The knowledge base is organized such that each paragraph encapsulates a self-contained legal idea or provision. This structure minimizes redundancy and facilitates efficient chunking, allowing a simple Python script to segment the documents paragraph-wise. For Bengali legal texts, manual or semi-automated translation into English was performed to ensure consistency and compatibility with English-language LLMs. Thus, legal provisions were split into semantically coherent chunks. This ensured effective retrieval and traceability when integrated into the RAG pipeline. The corpus includes the following content domains:

Bangladesh Penal Code, 1860: Selected sections on rape, miscarriage, and wrongful confinement relevant to gender-based violence cases.

Women and Children Repression Prevention Act, 2000: All sections related to women and child abuse, including punishment, procedural guidelines, and trial procedures in special tribunals.

Dowry Prohibition Act, 2018: Legal definitions, punishable offenses, and complaint mechanisms concerning dowry-related harassment and violence.

Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act, 2010: Documentation related to domestic violance, rights of aggrieved person, custody, and reconciliation procedures.

Cyber Security Ordinance 2025: Sections related to cyber harassment, threats, defamation, and unauthorized disclosure of private information, particularly relevant to online abuse cases.

NGO Legal Aid and Support Info: Helpline numbers, and legal aid procedures were extracted from reputable NGOs such as BRAC, Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), and Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST).

All documents were preprocessed using personal writing skills, noise removal, and sentence segmentation pipelines.

3.2. Language Model Configuration for RAG Generation

To generate grounded and contextually relevant responses based on retrieved legal documents, the Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) system employs the

llama3-8b-8192 model as the backbone language generator. This model belongs to Meta’s LLaMA 3 (Large Language Model Meta AI) family, which provides high-performance transformer-based architectures optimized for both instruction following and knowledge-intensive tasks [

34]. The specific 8B variant used here was accessed through the GROQ API, which offers real-time inference capabilities due to its high-throughput low-latency AI inference engine.

The llama3-8b-8192 model is trained on the corpus created before, enabling it to generalize well across structured and semi-structured legal content. Its architecture consists of approximately 8 billion parameters and supports a context window of 8192 tokens, allowing it to process and generate long, coherent outputs, especially useful in legal explanations and policy summarization. Key decoding parameters for the generation process include:

Temperature = 0.4: This parameter controls the randomness of token selection. Lower values (closer to 0) make the model more deterministic and focused, reducing variation in outputs. A value of 0.4 is selected to balance factual consistency with slight linguistic diversity in answers.

Max_tokens = 800: This setting determines the upper bound of tokens in the generated output. It ensures that the chatbot provides sufficiently informative responses without exceeding reasonable interaction length. The value can be tuned by the developer based on response verbosity requirements.

Stop Sequences and Prompt Formatting: Custom prompt templates were designed to encourage concise, empathetic, and legally accurate outputs. The model was conditioned to avoid speculative or hallucinated statements and to cite retrieved legal segments when available.

The model was not fine-tuned but instead used in a zero-shot or few-shot retrieval-augmented configuration, leveraging curated retrieval outputs for context grounding. This approach allowed for fast deployment while maintaining a high standard of reliability and explainability.

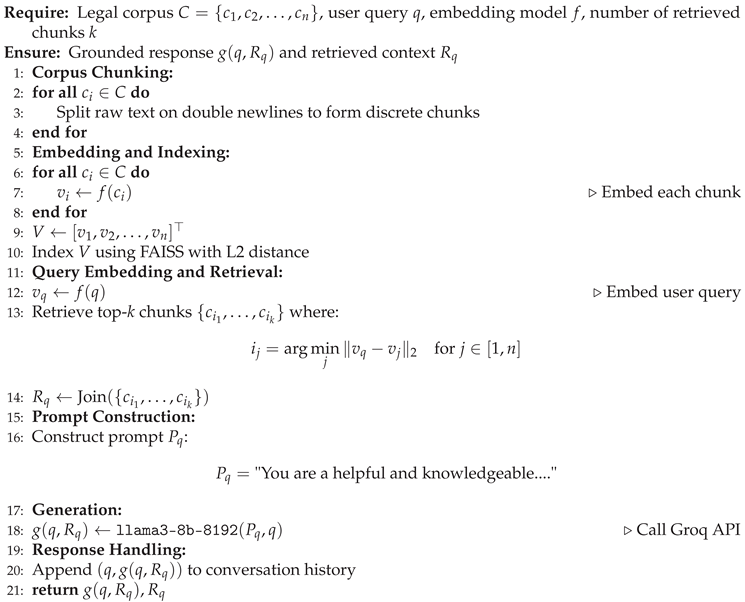

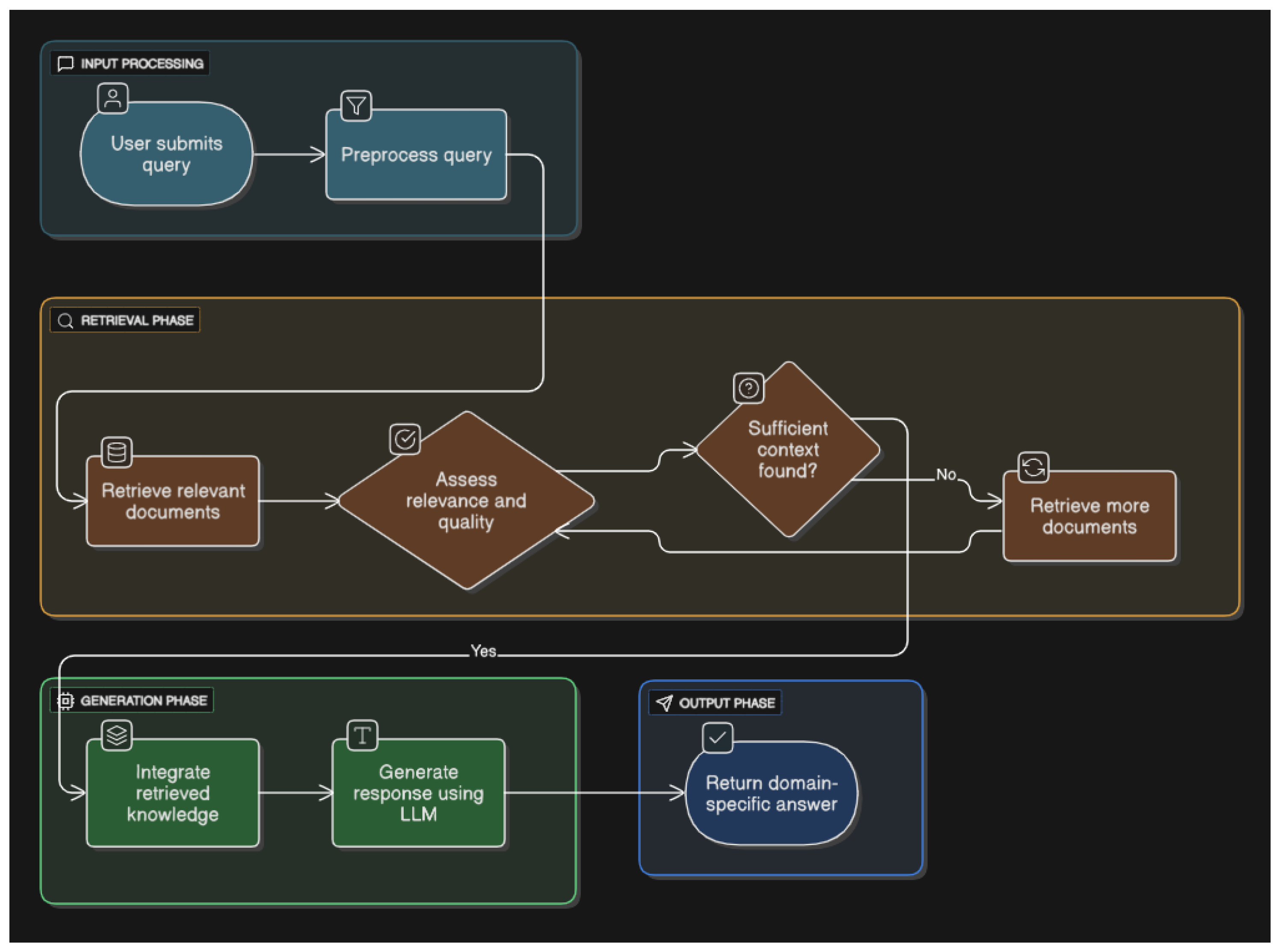

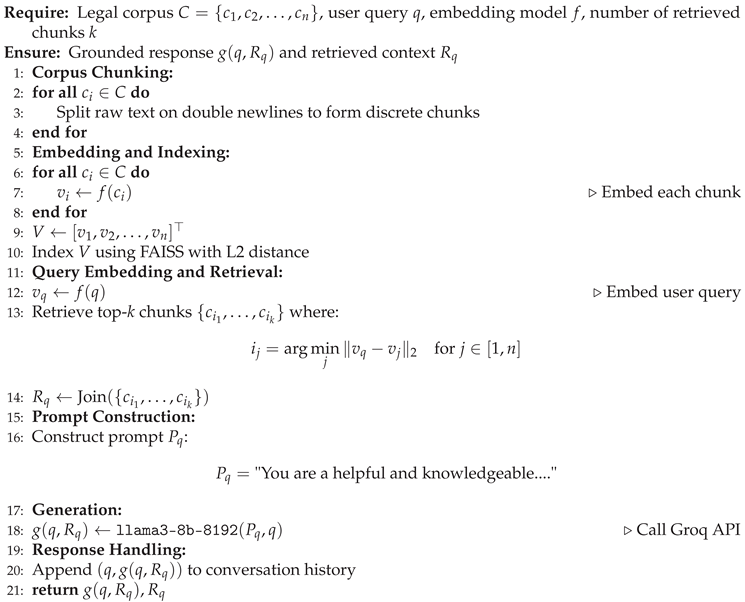

3.3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation Workflow

The core architecture follows a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline, in which a query-aware retriever identifies relevant textual chunks from a pre-embedded legal corpus, and a language model conditions its output on this retrieved context to produce grounded, human-readable responses. The general workflow for every RAG model is depicted in

Figure 1.

The system is composed of six modular stages as shown in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1 RAG-Based Legal Question Answering Workflow |

|

3.3.1. Corpus Chunking

Let denote the full corpus, consisting of n legal and institutional text paragraphs extracted from curated sources. Each paragraph is treated as a discrete chunk, forming the base retrieval unit. Chunks are created by splitting the raw text on double newlines.

3.3.2. Embedding with Sentence Transformer

Each chunk

is embedded into a dense vector representation

using the pre-trained

BAAI/bge-small-en-v1.5, a text embedding model developed by the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence (BAAI). The embedding function

maps all text into a

d-dimensional vector space:

The full matrix is indexed using FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search) for efficient nearest-neighbor search via L2 distance.

3.3.3. Indexing and Storage

FAISS stores the indexed vector representations of the corpus in a flat L2 index. This allows fast top-

k retrievals by computing:

where

q is the user’s input query.

3.3.4. Query Embedding and Context Retrieval

Upon receiving a user input

q, the system encodes it using the same sentence transformer

and retrieves the top-

k most semantically similar chunks:

The selected chunks are joined as a context string

for prompt conditioning.

3.3.5. Prompt Construction and Generation

The retrieved context is embedded into a custom system prompt:

"You are a helpful and knowledgeable AI assistant. Always respond based on the following trusted legal and institutional context: [retrieved text]"

The full prompt is then passed to the llama3-8b-8192 model via the Groq API. The model responds with a completion conditioned on both the query and retrieved context.

3.3.6. Response Handling and History Update

The chatbot appends each user–assistant pair to a conversational memory, enabling context-aware multi-turn interaction. The final response is returned alongside the retrieved chunks for evaluation and transparency.

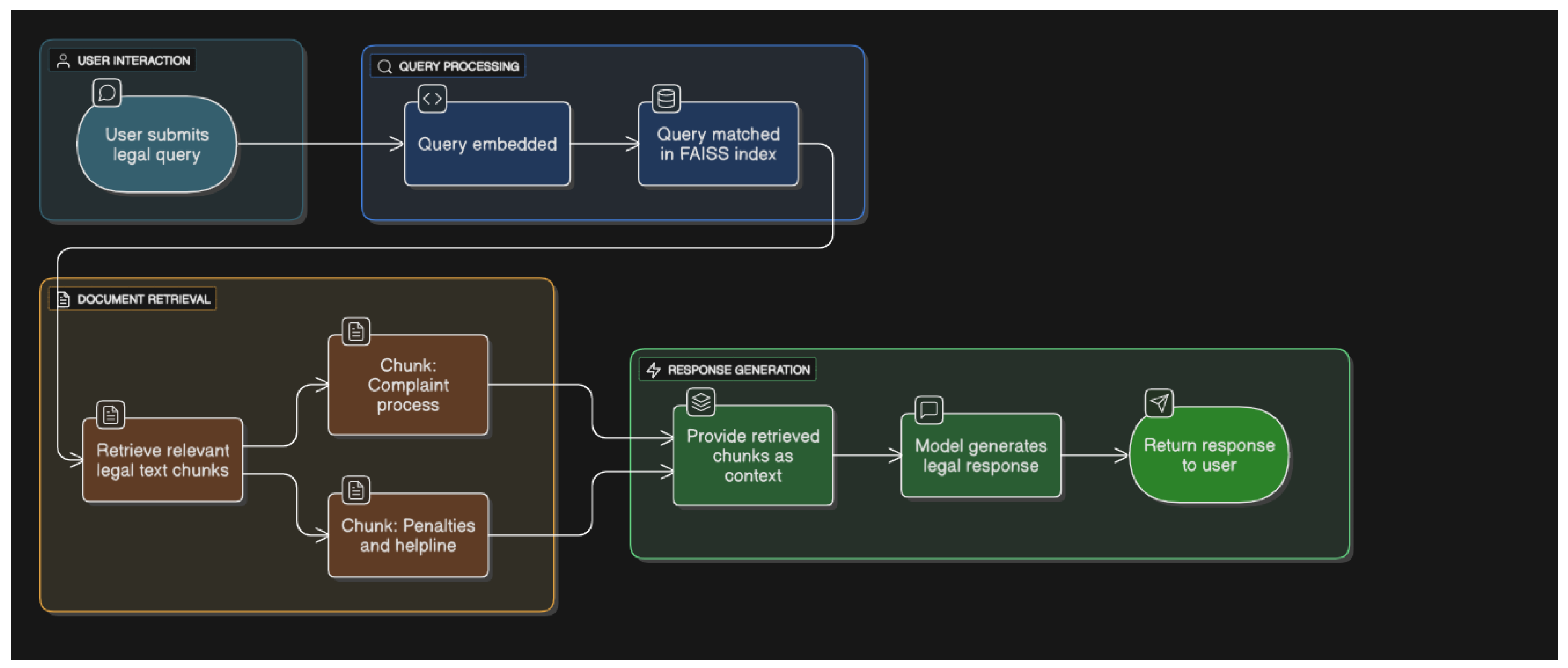

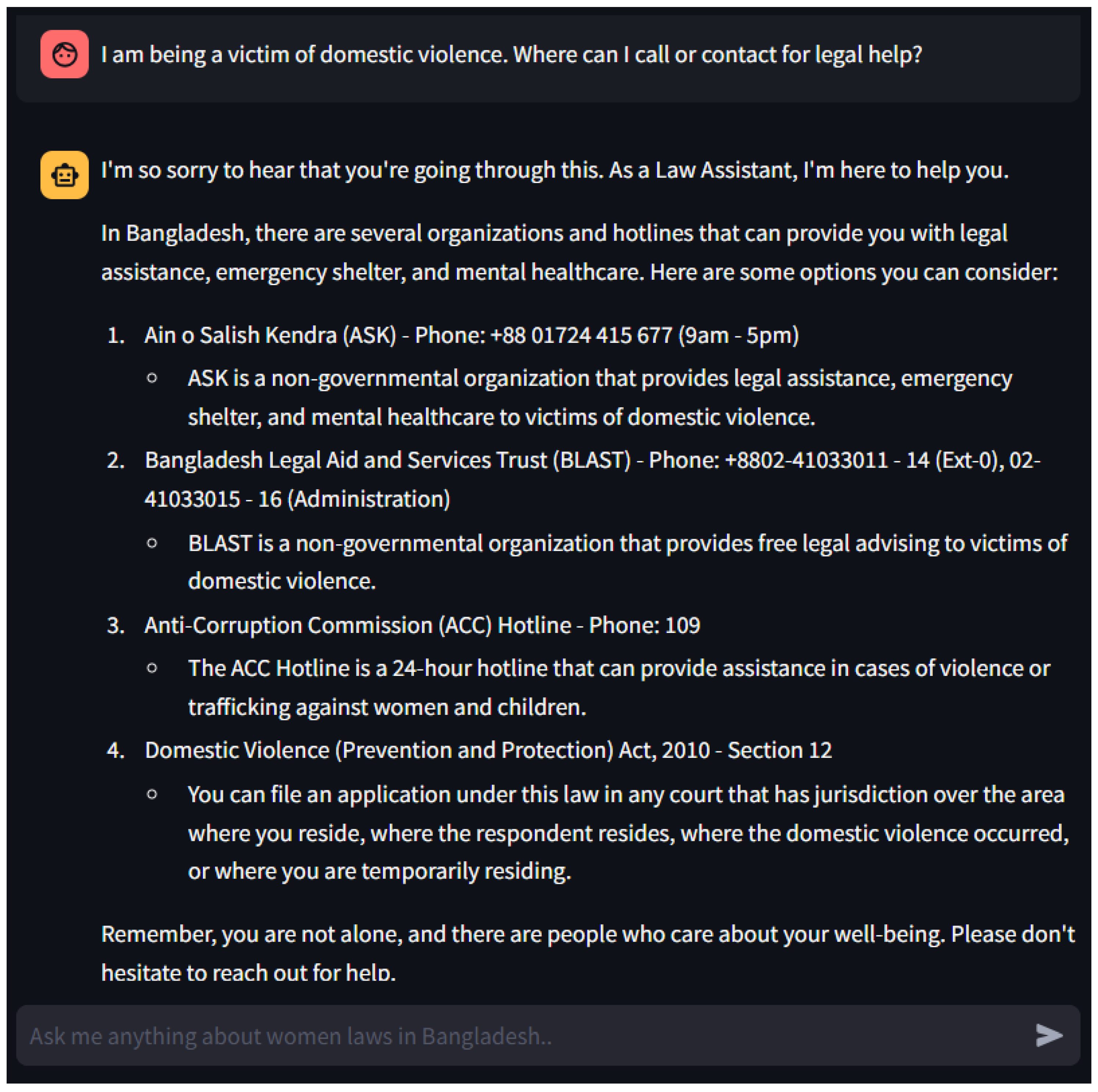

Illustrative Simulation: A Query–Response Example

User Input:"How can I file a complaint if my husband demands dowry after marriage?"

- 1.

The query q is embedded and matched against the FAISS index.

- 2.

-

Two retrieved chunks from the Dowry Prohibition Act 2018 are returned:

- 3.

The model is prompted with this legal context and returns:

"Under the Dowry Prohibition Act 2018, demanding dowry after marriage is illegal and punishable. You may file a complaint at your local police station or call the government helpline 109. Legal aid is also available through NGOs like ASK or BLAST."

This simulation illustrates the transparent retrieval–generation pipeline, ensuring that the chatbot outputs are both relevant and verifiable.

3.4. Deployment, Safety, and Usage Safeguards

The JusticeNetBD application is publicly deployed using Streamlit Cloud, enabling seamless browser-based interaction without requiring installation or configuration on the user’s end. The app is accessible to any user in Bangladesh or globally with a lightweight interface.

The application is currently in its beta phase and may face scalability limitations under heavy concurrent usage. Given that Streamlit Community Cloud offers limited resource allocation (e.g., single-threaded execution and capped compute time), the app is optimized for lightweight interactions and is best suited for individual or low-traffic use cases. Despite such constraints, user comfort is prioritized via fast semantic search and clear error handling mechanisms. Furthermore, the app does not implement automatic session expiry currently, so users are advised not to leave it inactive for extended periods to avoid unexpected resets, loss of chat history, or other security concerns.

Figure 3 depicts a portion of the user interface of JusticeNetBD.

Figure 4 shows a conversation between a user and the model.

To ensure secure interaction, session-level isolation is enforced through a per-user session identifier generated using uuid. This design ensures that each user maintains their own private session history, thereby avoiding shared state or cross-user data leakage. Streamlit’s session_state is used exclusively in-memory during the session and is cleared upon session expiration or browser reset, thereby maintaining short-term privacy and avoiding persistent data retention. No user-identifiable information or chat logs are stored server-side beyond the runtime. Users can also delete their chat history to overcome API errors.

To prevent abuse or misuse of the model’s API endpoint and to throttle aggressive prompting behaviors, a mandatory 5-second cooldown is enforced after each user prompt. If a user attempts to send multiple prompts in rapid succession, a warning is shown and the input interface is temporarily locked. This basic form of rate-limiting serves both technical purposes (avoiding token quota overflow on the GROQ API) and ethical enforcement by deterring spammy interactions.

Robust safety guidelines are incorporated into the system prompt to proactively filter harmful content. Specifically, the model is explicitly instructed to avoid generating unsafe, violent, or offensive content. If a user enters an abusive, derogatory, or otherwise inappropriate prompt, the model is instructed to decline responding and politely request respectful behavior. This safeguards the system against toxic use cases, particularly important given the sensitive legal context and vulnerable user base the app serves.

Prompt injection attacks are not a viable threat in this system for several reasons. First, the underlying model has no access to confidential data or backend controls, it is strictly limited to answering questions based on a closed corpus of public legal documents. Second, since the system prompt is regenerated with each user input and not user-controllable, adversarial prompt modifications do not persist or affect future interactions. Finally, no dynamic API calls, file access, or backend execution commands are exposed in the model’s response mechanism, significantly minimizing the risk surface.

In addition, users are shown an explicit disclaimer informing them that the tool is experimental and not a substitute for professional legal advice. This legal safeguard aligns with ethical research practices and ensures transparency during public beta deployment.

3.5. Performance Evaluation Metrics

To rigorously assess the quality and effectiveness of the proposed RAG-based Legal Assistant, both retrieval-level and generation-level metrics are employed. These metrics are designed to evaluate how accurately relevant information is retrieved from the corpus and how coherently and factually correct the generated responses are. The chosen evaluation metrics include Recall@k, Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR), ROUGE-L, and BERTScore-F1.

3.5.1. Recall@k

Definition: Recall@k measures the proportion of relevant documents or chunks that are retrieved among the top-k results. It is commonly used in information retrieval to evaluate how effectively a system retrieves relevant items.

Interpretation: A higher Recall@k indicates that the model is more effective at retrieving relevant information within the top-k retrieved results. In practice, when the total number of relevant documents is unknown or assumed to be 1 (as in many QA tasks), Recall@k simplifies to a binary value (0 or 1) indicating whether a relevant item appeared in the top-k.

3.5.2. Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR)

Definition: MRR evaluates the ranking quality of the retrieved results by computing the reciprocal of the rank at which the first relevant item appears. It is the average of these reciprocals over all queries.

Formula:

where

is the position of the first relevant result for the

i-th query.

Interpretation: MRR values range from 0 to 1. A higher MRR indicates that relevant results tend to appear earlier in the ranked list.

3.5.3. ROUGE-L

Definition: ROUGE-L (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation - Longest Common Subsequence) is a metric for evaluating the similarity between a generated sequence and a reference by measuring the length of their Longest Common Subsequence (LCS). It focuses on recall by quantifying how much of the reference text is preserved in the generated output.

Formula: Let

X be the reference text and

Y be the generated text.

Interpretation: ROUGE-L emphasizes recall, i.e., how much of the reference is preserved in the system-generated output. It is particularly useful for tasks like summarization, where capturing essential information is critical.

3.5.4. BERTScore F1

Definition: BERTScore evaluates the semantic similarity between a generated response and a reference by computing token-level cosine similarities of contextual embeddings from a pretrained BERT model. It aligns tokens using greedy matching and computes precision, recall, and F1.

Formula: Let

be tokens in the reference, and

in the generated text. Let

denote contextual embeddings.

Interpretation: Unlike traditional n-gram based metrics, BERTScore captures deep semantic alignment. Higher scores indicate greater semantic similarity between predicted and reference texts.

In combination, these metrics provide a comprehensive picture of both the retrieval and generative performance of the RAG-based assistant, spanning retrieval precision, ranking quality, syntactic similarity, and semantic fidelity.

The proposed model is evaluated against three state-of-the-art (SOTA) and commercial large language models (LLMs) in a closed-book system. These models are ChatGPT-4o Turbo, Gemini Flash 2.5, and DeepSeek-V3. In the context of language models, a closed-book system refers to one that generates answers solely based on the knowledge encoded within its parameters, without access to external documents or databases at inference time. Such models do not retrieve or consult any supplementary information, relying entirely on pre-trained knowledge. To ensure a fair comparison, all SOTA models were explicitly prompted not to use any external search or retrieval capabilities, and to rely solely on their pretrained knowledge. Allowing access to search functions could unfairly advantage them over the proposed RAG-based model, JusticeNetBD, by retrieving potentially helpful external information. Conversely, search results from unreliable or irrelevant sources could degrade their performance, unfairly disadvantageing them against the proposed model. In both cases, such access would introduce bias into the evaluation. Therefore, to maintain consistency, all models were constrained to operate using only their internal pretrained knowledge. Afterward, a set of legal queries was presented to the SOTA models, and their responses were evaluated using ROUGE-L and BERTScore F1, comparing against ground-truth legal answers. These scores were then compared with those of the proposed JusticeNetBD model.

Besides evaluating retrieval and generation metrics, model inference time is also analyzed between the models to robustly analyze the efficiency and practical usability of JusticeNetBD. Model inference times are analyzed through exploratory data analysis (EDA) of response time distributions across all queries. Statistical significance is assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction, establishing robust performance differences between model architectures.

4. Results and Discussion

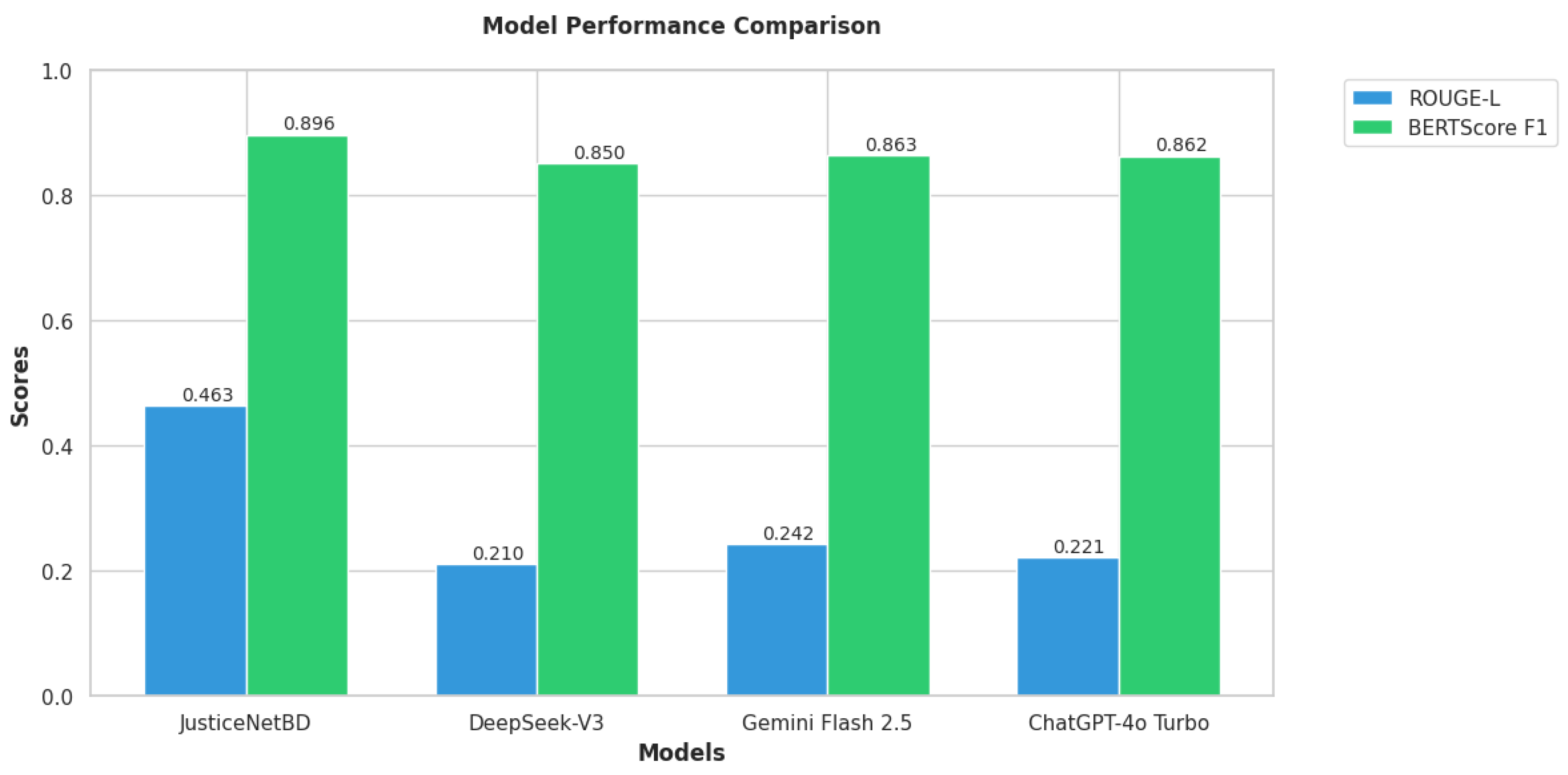

The model performance is assessed from two complementary angles. Only the RAG model (JusticeNetBD) produces an explicit list of evidence passages, so recall@k and MRR are reported only for this model. For all models, JusticeNetBD and three state-of-the-art (SOTA) closed-book LLMs, ROUGE-L and BERTScore F1 are computed as well.

4.1. Quantitative Results

The RAG system achieves recall@2 = 0.90 and MRR = 0.90, demonstrating that the sentence-transformer combined with FAISS effectively retrieves the relevant clauses from the Bangladeshi legal corpus. This high retrieval fidelity translates into improved answer quality, with ROUGE-L scores increasing by +23–25 percentage points and BERTScore F1 by +3–5 percentage points compared to all closed-book large language models (LLMs).

Table 1.

Average performance over the 10-question legal QA benchmark. R-L = ROUGE-L, BS = BERTScore F1. Only the proposed model produces retrieval metrics.

Table 1.

Average performance over the 10-question legal QA benchmark. R-L = ROUGE-L, BS = BERTScore F1. Only the proposed model produces retrieval metrics.

| Model |

Recall@2 |

MRR |

R-L |

BS |

| JusticeNetBD |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.463 |

0.896 |

| DeepSeek V3 (Closed-Book) |

n/a |

n/a |

0.210 |

0.850 |

| Gemini Flash 2.5 (Closed-Book) |

n/a |

n/a |

0.242 |

0.863 |

| ChatGPT 4o-Turbo (Closed-Book) |

n/a |

n/a |

0.221 |

0.862 |

General-purpose state-of-the-art large language models such as DeepSeek-V3, Gemini Flash 2.5, and ChatGPT-4o underperform in this domain due to their lack of access to domain-specific legal statutes relevant to Bangladesh, as shown in

Figure 5. As a result, these models tend to produce generic legal advice or reference incorrect statutory sections, which adversely affects lexical overlap metrics (e.g., ROUGE-L) and, to a lesser extent, semantic similarity measures such as BERTScore F1.

Incorporating exact statutory text segments into the prompt allows the RAG model to:

Mitigate hallucination: ensuring that every generated claim can be traced to retrieved source text.

Enhance lexical fidelity: resulting in improved ROUGE-L scores due to accurate legal phrasing.

Preserve linguistic fluency: maintaining BERTScore values comparable to human-generated responses.

4.2. Inference Time Analysis

As mentioned before, model inference comparison analysis is conducted to assess the efficiency of the proposed model.

Table 2 shows each model’s inference speed to each user queries.

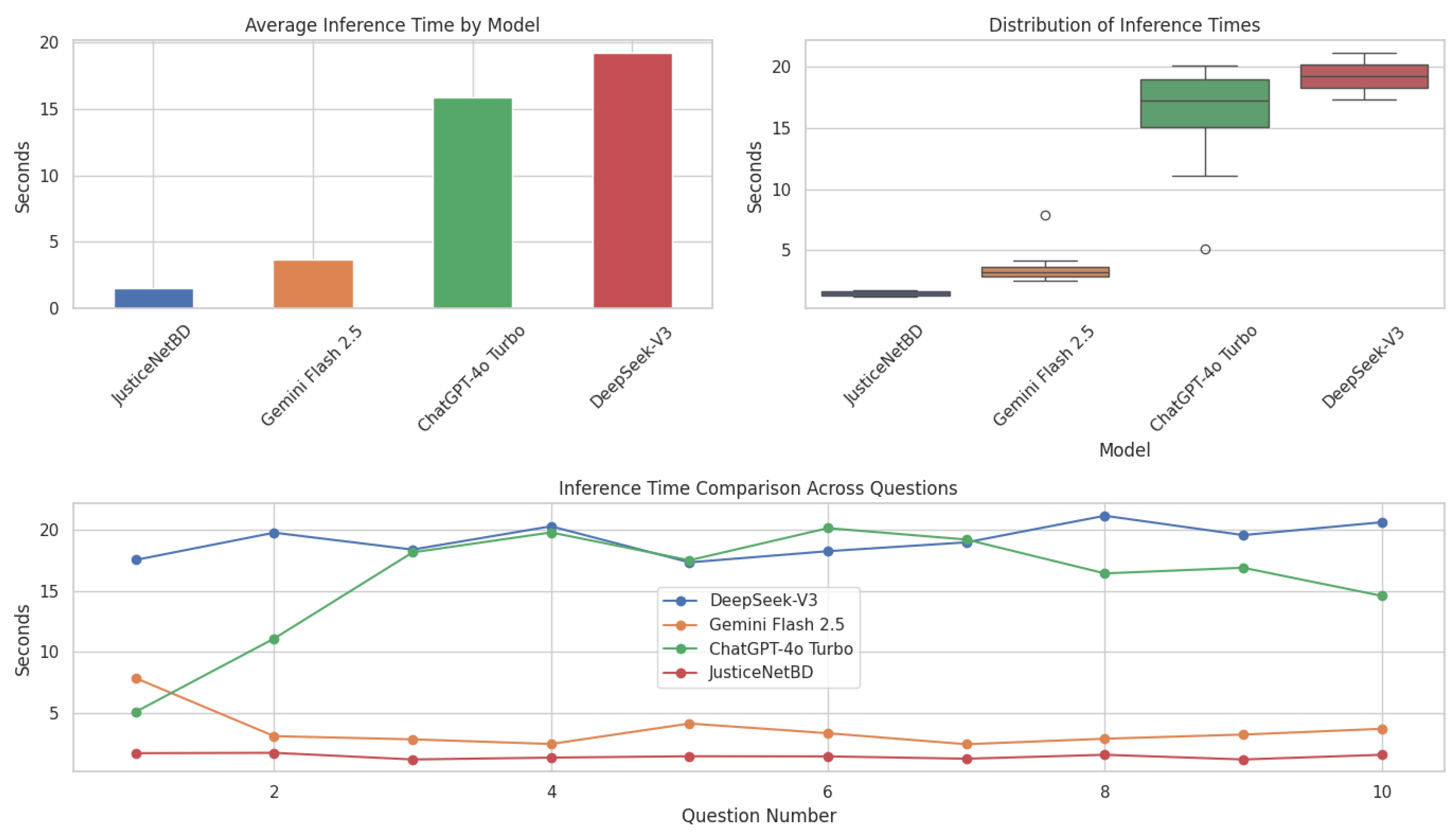

Figure 6 presents a comparative analysis of inference times across the four different language models. The top-left bar chart illustrates the average inference time for each model. JusticeNetBD demonstrates the lowest average inference time, taking approximately 1–2 seconds per query. In contrast, DeepSeek-V3 and ChatGPT-4o Turbo show significantly higher latency, with average times nearing 20 and 16 seconds respectively. Gemini Flash 2.5 stands in between, averaging around 3.5 seconds.

The top-right box plot captures the distribution of inference times, highlighting the variability in response durations. JusticeNetBD exhibits a tight, consistent distribution, indicating high reliability and low variance in response times. Gemini Flash 2.5 also maintains relatively low variance, although with an outlier. On the other hand, ChatGPT-4o Turbo and DeepSeek-V3 display much broader distributions, suggesting inconsistent and slower performance across queries. The bottom line graph provides question-wise (query-wise) comparison of inference times across ten distinct queries. It further reinforces the consistent performance of JusticeNetBD, which remains nearly flat and minimal throughout. In contrast, DeepSeek-V3 and ChatGPT-4o Turbo exhibit noticeable fluctuations, with multiple peaks and relatively high latencies. Gemini Flash 2.5 shows moderate and slightly varying inference times. Overall, the results clearly demonstrate that JusticeNetBD achieves the most efficient and consistent inference performance among the evaluated models, making it more suitable for real-time and latency-sensitive applications.

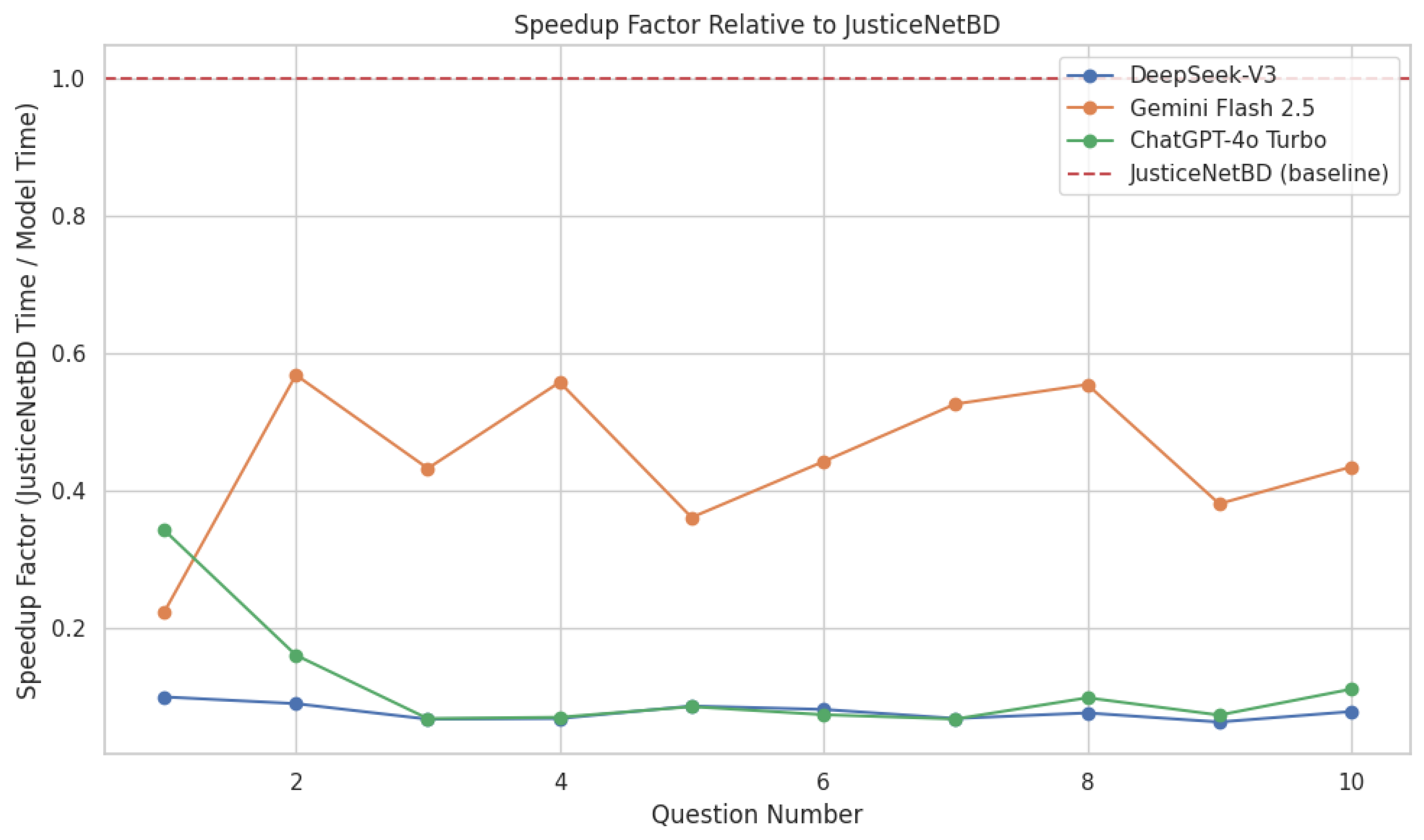

Figure 7 presents a comparison of the speedup factor of three large language models, relative to JusticeNetBD. The speedup factor is calculated as the ratio of JusticeNetBD’s inference time to that of the corresponding model.

The baseline is marked with a red dashed line at speedup = 1.0, which corresponds to JusticeNetBD itself. Any point below this line indicates that the compared model is slower than JusticeNetBD for that particular query.

Across all ten questions, JusticeNetBD consistently outperforms the other models in terms of inference time. DeepSeek-V3 and ChatGPT-4o Turbo maintain speedup values mostly below 0.1, indicating that JusticeNetBD is approximately 10 times faster than these models. Their speedup values are relatively stable and low, confirming that their inference time is significantly higher across all tested queries.

Table 3 also summarizes that JusticeNetBD significantly outperforms the other models in average inference time, with the lowest mean and smallest error margin.

The observed speed degradation in ChatGPT-4o Turbo may be attributed to its internal reasoning mechanism. Despite explicit restrictions on web search functionality, the model’s inherent "chain-of-thought" processing introduces computational overhead, resulting in slower response times compared to more streamlined architectures. Gemini Flash 2.5, while still slower than JusticeNetBD, performs better than the other two models in terms of relative efficiency. Its speedup values range from approximately 0.2 to 0.57 across different questions. Although not close to the baseline, this indicates that Gemini Flash 2.5 provides a moderate trade-off between latency and computational cost, being about 2–5 times slower than JusticeNetBD depending on the query. In summary, the plot highlights that JusticeNetBD achieves the highest computational efficiency, establishing itself as the fastest model in the benchmark. The consistently low speedup values of other models further emphasize JusticeNetBD’s potential for real-time legal assistant applications where latency is critical.

Statistical Significance Test

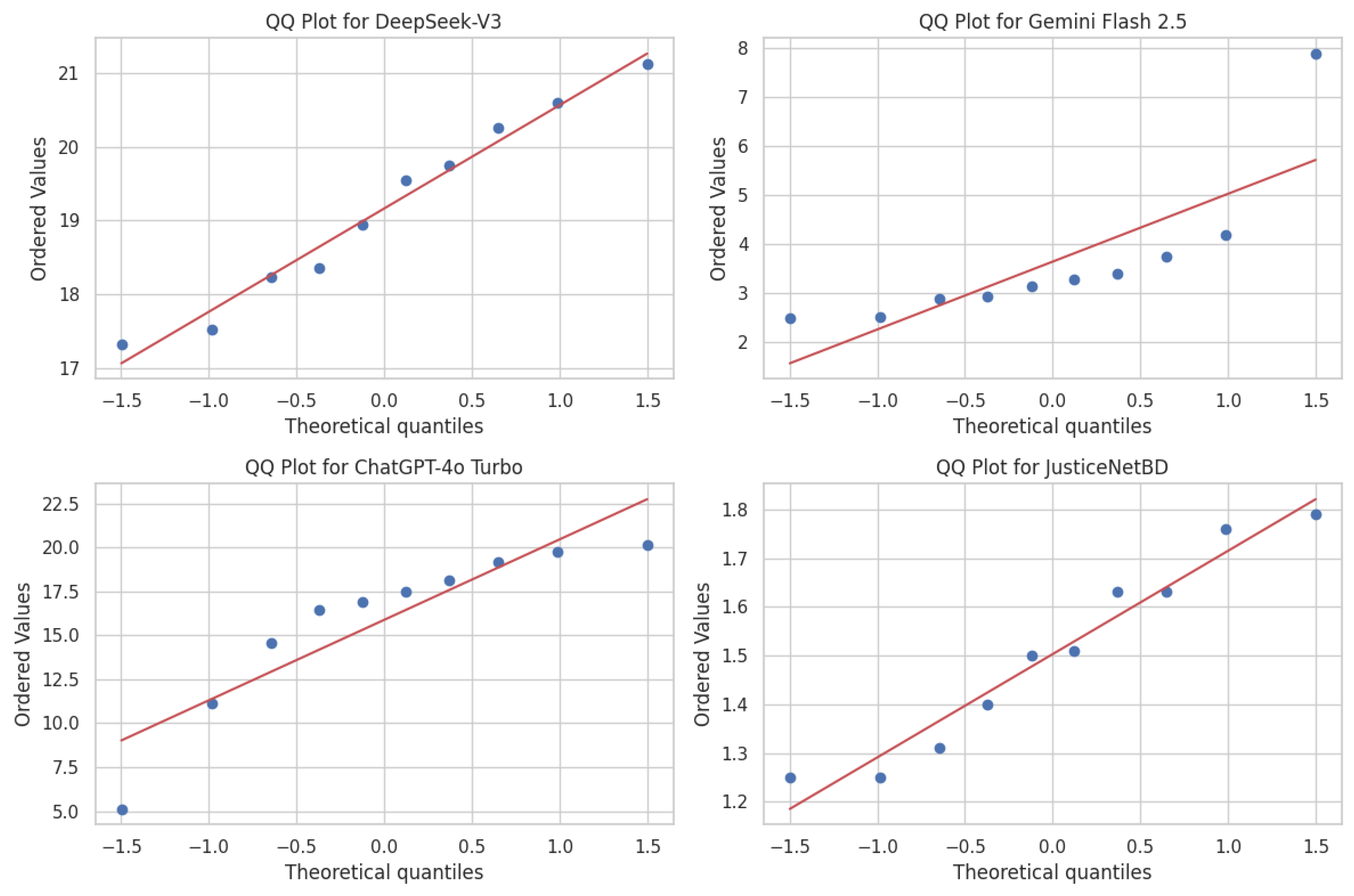

Figure 8 displays the Q-Q plots of inference times for each model, used to assess normality. The points for JusticeNetBD and DeepSeek-V3 lie relatively close to the reference line, indicating that their inference times approximate a normal distribution. ChatGPT-4o Turbo, however, exhibits noticeable deviation in the lower quantiles, suggesting a potential right skew or presence of outliers. Gemini Flash 2.5 shows significant divergence from the line at both tails, implying the data deviates from normality, possibly due to outlier influence or a heavy-tailed distribution.

Since the assumption of normality was violated, it is not appropriate to apply parametric tests that assume both normal distribution and homoscedasticity (equal variances). Thus, homoscedasticity tests such as Bartlett’s or Levene’s are unnecessary. In such cases, non-parametric tests provide a more reliable alternative. Given that the experiment involves more than two groups and the data is non-normally distributed, the Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted. The result shows a Kruskal–Wallis H-statistic of 33.90 with a p-value of , indicating a statistically significant difference in inference times among the models at . To identify which specific model pairs contribute to this difference, Dunn’s post-hoc test was subsequently applied.

The Kruskal–Wallis

H-statistic is calculated using the following formula:

where:

k is the number of groups,

is the number of observations in group i,

is the sum of ranks for group i,

N is the total number of observations across all groups.

Analysis of Results

The Dunn’s post-hoc test following a significant Kruskal-Wallis test reveals several important pairwise comparisons among the models’ inference times:

-

JusticeNetBD vs. Other Models:

- –

Shows highly significant differences compared to ChatGPT-4o Turbo () and DeepSeek-V3 ()

- –

No significant difference from Gemini Flash 2.5 ()

-

Gemini Flash 2.5 Performance:

- –

Significantly faster than DeepSeek-V3 ()

- –

Marginally faster than ChatGPT-4o Turbo (, not significant at )

-

Top-tier Models Comparison:

- –

No significant difference between ChatGPT-4o Turbo and DeepSeek-V3 ()

The results suggest that JusticeNetBD is statistically significantly faster than both ChatGPT-4o Turbo and DeepSeek-V3, while performing similarly to Gemini Flash 2.5. Among the commercial models, Gemini Flash 2.5 demonstrates superior speed performance compared to DeepSeek-V3, though not significantly different from ChatGPT-4o Turbo. The lack of difference between ChatGPT-4o Turbo and DeepSeek-V3 suggests these models have comparable inference speed characteristics in this legal domain application.

The results suggest that RAG models (using BAAI embeddings + FAISS) are significantly faster than closed-book LLMs. Probably because they offload knowledge retrieval to a fast, optimized vector database (FAISS), which quickly finds relevant documents, allowing a smaller and more efficient language model to generate answers based on this retrieved context. Unlike closed-book models that rely solely on their large internal parameters to recall information, requiring expensive and slow autoregressive computations, RAG models only process a focused subset of relevant data, reducing compute time and latency. Additionally, running retrieval and generation locally avoids API overhead and network delays common in commercial closed-book models, resulting in much faster overall response times.

However, despite strong retrieval performance, approximately 10% of queries fail to retrieve the gold-standard statutory chunk. This can be a result of colloquial query phrasing. It refers to how people naturally ask questions in everyday conversation, often using informal language, slang, abbreviations, or incomplete sentences rather than structured, formal queries. Future work could explore approaches such as query rewriting or hybrid sparse-dense retrieval methods to further improve recall towards 1.0. In the context of providing high-stakes legal advice, the grounded RAG system substantially outperforms closed-book state-of-the-art LLMs. The pipeline not only enhances factual accuracy but also offers transparent evidence retrieval, thereby providing a safer and more reliable tool for supporting women’s rights initiatives in Bangladesh.

5. Conclusion

The research presents JusticeNetBD, a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)-based legal assistant designed to enhance access to legal information for Bangladeshi women. By addressing the critical gaps in awareness and accessibility of legal protections, JusticeNetBD offers a scalable, efficient, and culturally sensitive solution to empower women with timely and accurate legal guidance. The system leverages a curated corpus of authoritative Bangladeshi legal documents and integrates advanced NLP techniques to deliver contextually grounded responses. Key findings demonstrate that JusticeNetBD outperforms state-of-the-art models like ChatGPT-4o Turbo, Gemini Flash 2.5, and DeepSeek-V3 in both retrieval accuracy (Recall@2 = 0.90, MRR = 0.90) and answer quality (ROUGE-L = 0.463, BERTScore F1 = 0.896). Notably, the system processes queries 10 times faster than ChatGPT-4o Turbo and DeepSeek-V3, and 2-5 times faster than Gemini Flash 2.5, making it highly suitable for real-time applications in resource-constrained settings. Statistical analyses confirm the significance of these performance differences, highlighting JusticeNetBD’s superior efficiency and reliability. The study underscores the transformative potential of AI in bridging the justice gap for women. By mitigating hallucination, enhancing factual accuracy, and providing transparent evidence retrieval, JusticeNetBD sets a benchmark for ethical and effective legal AI tools. Future work may incorporate expansion of the corpus to cover broader legal domains, improving retrieval for colloquial queries, and adding multilingual support to further enhance accessibility. In conclusion, JusticeNetBD represents a significant step toward democratizing legal knowledge and fostering equitable access to justice, particularly for vulnerable populations in Bangladesh. Its success paves the way for similar innovations in other Global South contexts, aligning technological advancements with societal needs.