2. Theoretical Foundations

The current section overlooks the theoretical foundations, as building blocks to gather all the threads together towards a new teaching practice of joyful teaching of mathematics.

2.1. Constructivism and Playful Learning

Constructivist theories hold that students actively produce knowledge via encounters and interactions (Stanford, 2020; McLeod, 2022). By encouraging inquiry, curiosity, and social interaction, fun activities like comedy help meaningful learning (Brown, 2023). When students like learning activities, they are more likely to internalise knowledge and create positive attitudes (Nesbitt et al., 2023).

The question of what makes humans unique compared to other animals has been debated for a long time(Stanford, 2020), with some people believing it is too complex to answer. Humans are very adaptable and display a great spectrum of actions (Stanford, 2020), which some claim are the outcome of millions of years of evolution rather than just products of personal imagination or society. Rather than the contemporary world we live in, the surroundings of our ancestors(Stanford, 2020) shape our brains. So, our actions may seem strange or old-fashioned.

In A Different Kind of Animal, (Stanford, 2020) investigated how people change to their surroundings mostly by blind mimicking of others rather than via deliberate preparation. He claims that our capacity to enforce social norms—rules directing conduct—is essential for advancing cooperation among large groups (Stanford, 2020), even with strangers. However(Stanford, 2020), pointing out that while we are good at following and enforcing norms, this can lead to the adoption of harmful or maladaptive behaviors, as the content of these norms isn't always beneficial.

Discussing the idea that human behavior and mental abilities are not strictly determined by our genes, as traditional evolutionary psychology suggests(Stanford, 2020) but are shaped by cultural evolution and our interactions with the environment. Some contend that rather of being born with set mental modules(Stanford, 2020), we have pliable tendencies that through cultural interactions become sophisticated abilities including language and social insight.

Challenging the idea of a fixed, "hard-wired" mind, this viewpoint stresses the brain's flexibility and the need of cultural influences in forming our cognitive capacities (Stanford, 2020). Against different perspectives on cultural development (Stanford, 2020), humans' behavior and cognitive capacities may change via mechanisms including blind imitation and cultural group selection.

It is stressed that cultural success is driven by blind imitation (Stanford, 2020), rather than intellect, while arguing that what we call intelligence may also be affected by cultural influences. Together (Stanford, 2020), these ideas question accepted views by suggesting that better knowledge of human nature inside the larger framework of evolutionary theory may be attained by the simultaneous development of both cultural conventions and cognitive processes.

The 1983 release of "A Nation at Risk" sparked major education reforms in the U. S. , including the Common Core standards and the No Child Left Behind Act, all meant to raise math and reading abilities (Nesbitt et al. , 2023). But (Nesbitt et al. , 2023), these attempts did not produce the desired outcomes, therefore narrowing the curriculum and adding more strain for teachers and pupils. The persistent chance disparities for low-income and minority students underscore the necessity of a more efficient (Nesbitt et al. , 2023), student-centered approach to education that stresses enjoyable and engaging learning experiences especially in the wake of hurdles presented by the COVID-19 epidemic.

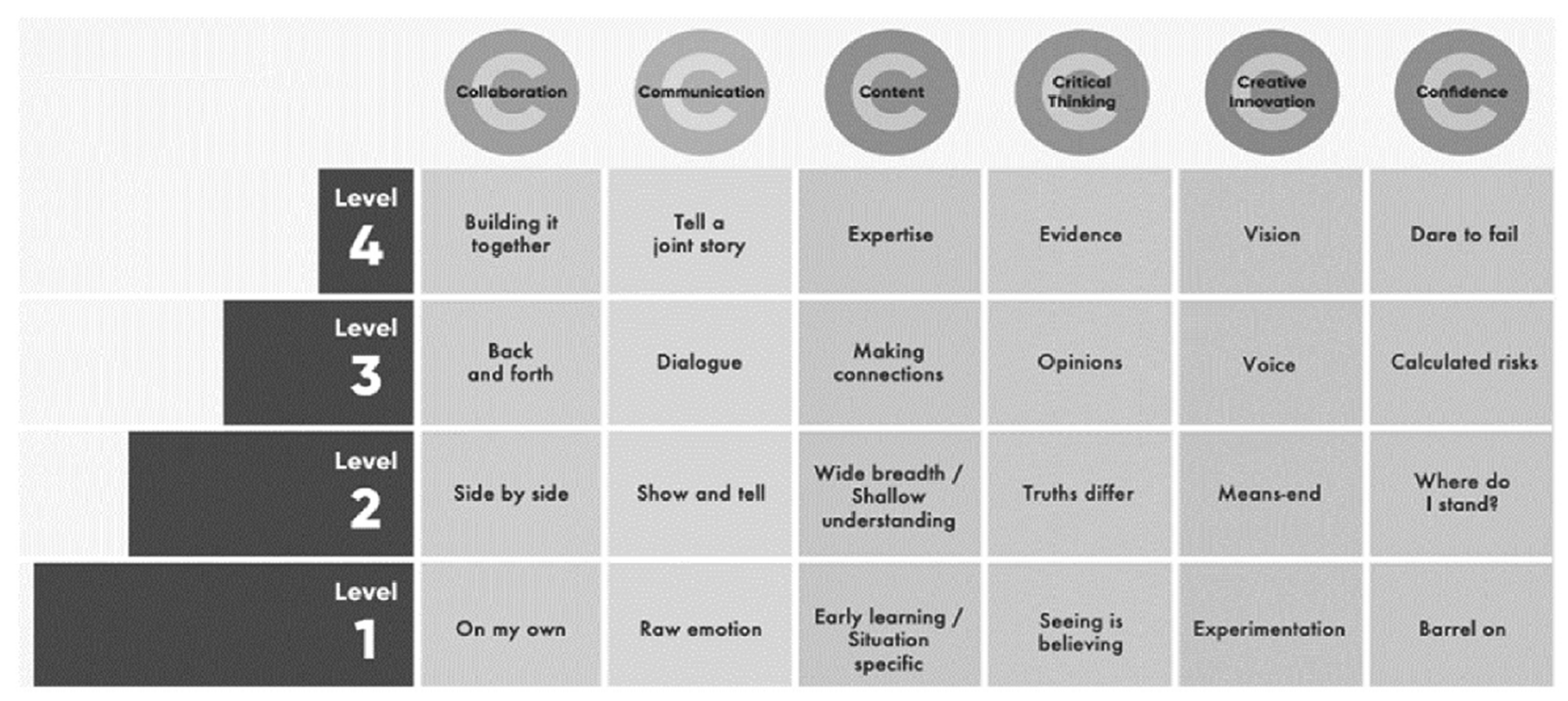

Defining success depends on the acquisition of basic academic knowledge(Nesbitt et al. , 2023) like mathematics and science, yet it is just as vital to cultivate more general abilities like creativity, critical thinking, teamwork, and communication—together known as the 6 Cs. These abilities are developed throughout one's life and are essential for both personal and professional success(Nesbitt et al. , 2023). Children who participate in social activities and collaborative projects—which helps them to deepen their understanding of content and apply their knowledge to solve problems—effective learning results from these interactions.

Creative invention depends on a thorough grasp of how things operate as this awareness enables us to spot opportunities for development (Nesbitt et al. , 2023).

The creation of household appliances, for instance, demonstrates how innovation arises from critical thinking and inquiry on current technologies (Nesbitt et al. , 2023). Furthermore, vital is having the self-assurance to keep going despite setbacks; it promotes a growth attitude and tenacity, allowing people to take chances and keep investigating fresh ideas (Nesbitt et al. , 2023).

Understanding the beliefs and priorities of the community in which pupils live—which may be gleaned by asking pupils, their families, and community members about what they find significant—is cultural values. The science of how children learn centers on studying successful learning techniques including directed play, which promotes investigation and discovery(Nesbitt et al. , 2023).

Translating scientific results into classroom practice entails making sure that lesson plans include interesting and interactive activities relevant to students, therefore creating a happy learning environment that encourages social involvement and active participation (Nesbitt et al. , 2023).

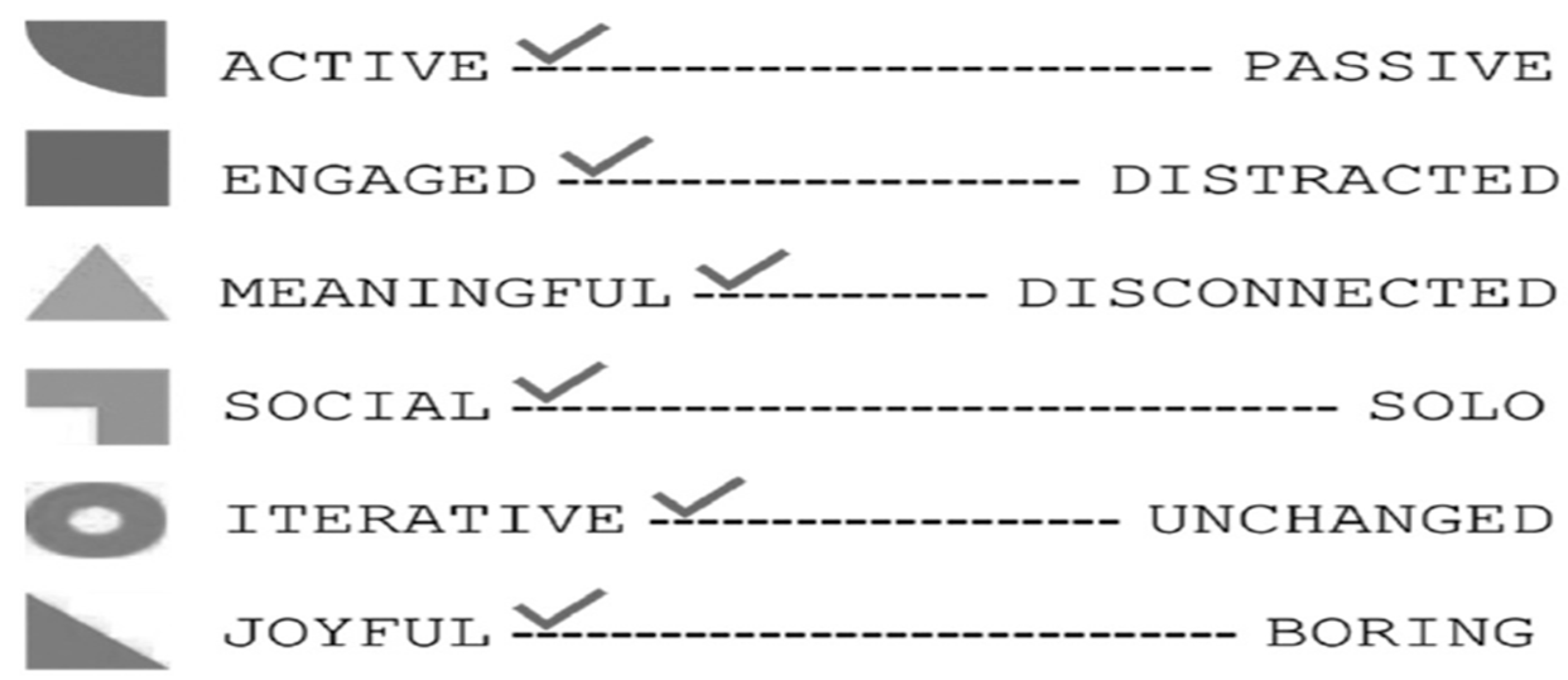

The "Active Playful Learning Checklist" stresses that teachers should create lessons that include aspects that make the learning process dynamic and pleasurable in addition to being concentrated on learning goals.

Teachers can thereby improve student learning and growth holistically—as depicted in

Figure 1 (Hirsh-Pasek et al. , 2020)—by following this checklist: active lessons that encourage both physical and mental participation; interesting lessons that capture their interest; relevant lessons connecting to their lives; social lessons promoting peer interaction; iterative lessons allowing for repeated practise and improvement; and joyful lessons fostering a positive learning environment.

The science of what children need to know focuses on identifying the specific skills that students are developing through their classroom activities(Nesbitt et al., 2023). This approach emphasizes the importance of considering the whole child, which means recognizing their emotional, social, and cognitive needs(Nesbitt et al., 2023).

To effectively assess and support this development, educators can use the 6 Cs grid checklist, which outlines essential skills such as critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, communication, citizenship, and character, ensuring a well-rounded educational experience, as depicted in

Figure 2 (c.f., Golinkoff and Hirsh-Pasek, 2016).

2.2. Cognitive Load Theory

According to Klein(2023) cognitive load theory, learning can be maximised by reducing unnecessary stress. By lowering the tension and apparent difficulty of complicated subjects, humour helps free up cognitive resources for processing important information (Bitterly, 2022). Funny examples or well-timed jokes can operate as cognitive anchors, humanising abstract concepts.

Achieving our goals when the solution isn't clear often requires critical thinking and creativity. Mental blocks, such as fear of failure or rigid thinking(Klein, 2023), can hinder our problem-solving abilities. By leveraging our prior knowledge and experiences, we can approach new problems more effectively(Klein, 2023), using what we already know to generate innovative solutions and overcome obstacles. In simple terms, this can be viewed as playing Chess, as in

Figure 3 (c.f., Klein, 20230.

In deep explorations of concept of a problem, defining it as a situation where there is a difference between the current state and a desired goal (Klein, 2023). Various strategies for problem-solving, starting from early psychological theories to modern approaches involving artificial intelligence, are thoroughly discussed(Klein, 2023). The focus is on non-trivial, abstract problems, which are categorized into well-defined problems (with clear solutions) and ill-defined problems (which are more complex and require deeper thought) (Klein, 2023).

There are two types of problems: well-defined and ill-defined. Well-defined problems have clear starting points, rules for how to manipulate those points, and specific goals, making them suitable for algorithmic solutions, like chess(Klein, 2023). In contrast, ill-defined problems, such as creating art or writing an essay, lack clear parameters and often require creativity and personal interpretation, which can involve breaking them down into smaller, well-defined sub-problems to find a solution(Klein, 2023). As visually showcased by

Figure 4 (c.f., Klein, 2023), the insight problem presented involves Knut trying to connect four pieces of a chain into a closed loop while managing a budget of 15 cents. Each link can be opened for 2 cents and closed for 3 cents. To solve the problem efficiently, Knut should consider how many links need to be opened or closed to minimize costs while achieving the goal of forming a closed loop.

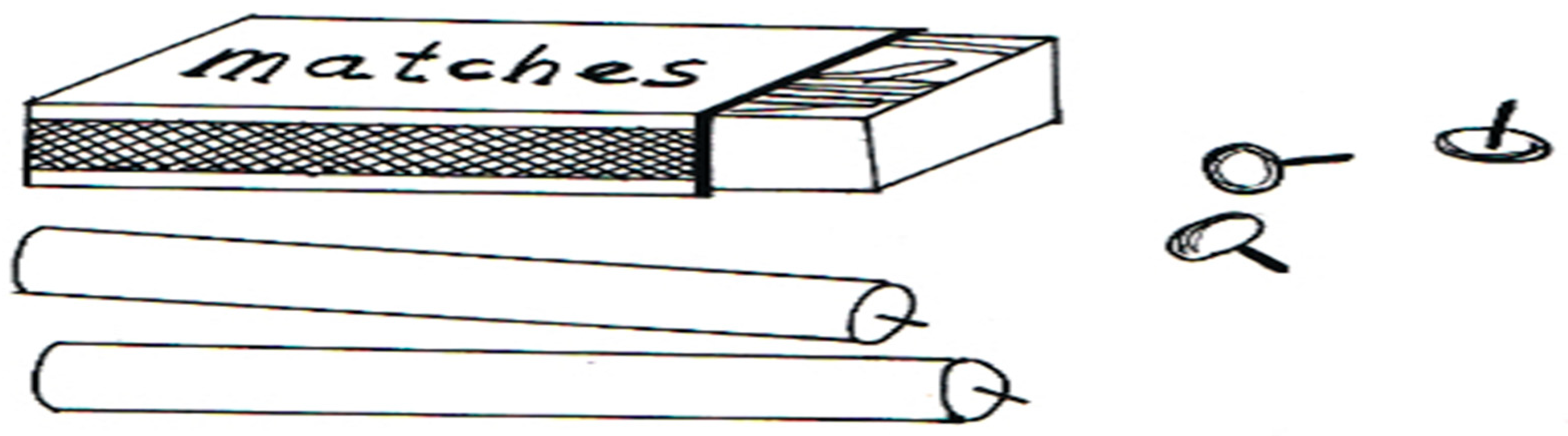

Functional fixedness is a cognitive bias that limits a person's ability to use an object in a new or creative way because they focus on its typical function(Klein, 2023). For example, in the candle problem, people often struggle to see that the box of matches can be used as a holder for the candle instead of just thinking of it as a container for matches (Klein, 2023).

This bias can hinder problem-solving and creativity, as it restricts our thinking to conventional uses of objects, as depicted in

Figure 5 (Klein, 2023).

Functional fixedness is a cognitive bias where individuals use objects only in the way they are traditionally used, making it hard for them to think of alternative uses (Klein, 2023), as seen with Knut using pliers only as tools instead of weights for a pendulum. This concept is illustrated through verbal insight problems, like the water lily example, where people often give incorrect answers due to misinterpreting the problem(Klein, 2023). Studies show that while feedback can sometimes help correct these misunderstandings, if someone is fixated on their initial incorrect interpretation, they may struggle to find the right solution even when told their answer is wrong (Klein, 2023).

Analogical problem solving is a strategy where a solution to one problem (the target problem) is found by using a similar solution from another problem (the base problem). In the radiation problem posed by (Duncker and Lees, 1945; Gick and Holyoak,1980) to destroy a tumor without harming healthy tissue, like how a general must capture a fortress while avoiding landmines. The solution involves splitting the high-intensity ray into weaker rays, akin to dividing the army into smaller groups, allowing them to safely reach the tumor and destroy it without damaging surrounding healthy tissue.

Gick and Holyoak(1980) identified three key steps in analogical problem solving based on their research. First, individuals must recognize that there is a connection between a familiar problem (the source) and a new problem (the target). Next, they need to map the elements of the two problems to each other, such as relating the fortress to the tumor and the army to the ray. Finally, they apply this mapping to create a solution for the target problem, like using weaker rays from different angles to effectively destroy the tumor without harming healthy tissue.

2.3. Affective Domain and Motivation

Gimeno Sacristán (2021) described the affective domain as one that affects students' attitudes, motivation, and level of involvement. Xing (2023) has shown that humour enhances attitude, lowers mathematics anxiety, and motivates people. These emotional advantages foster more in-depth learning.

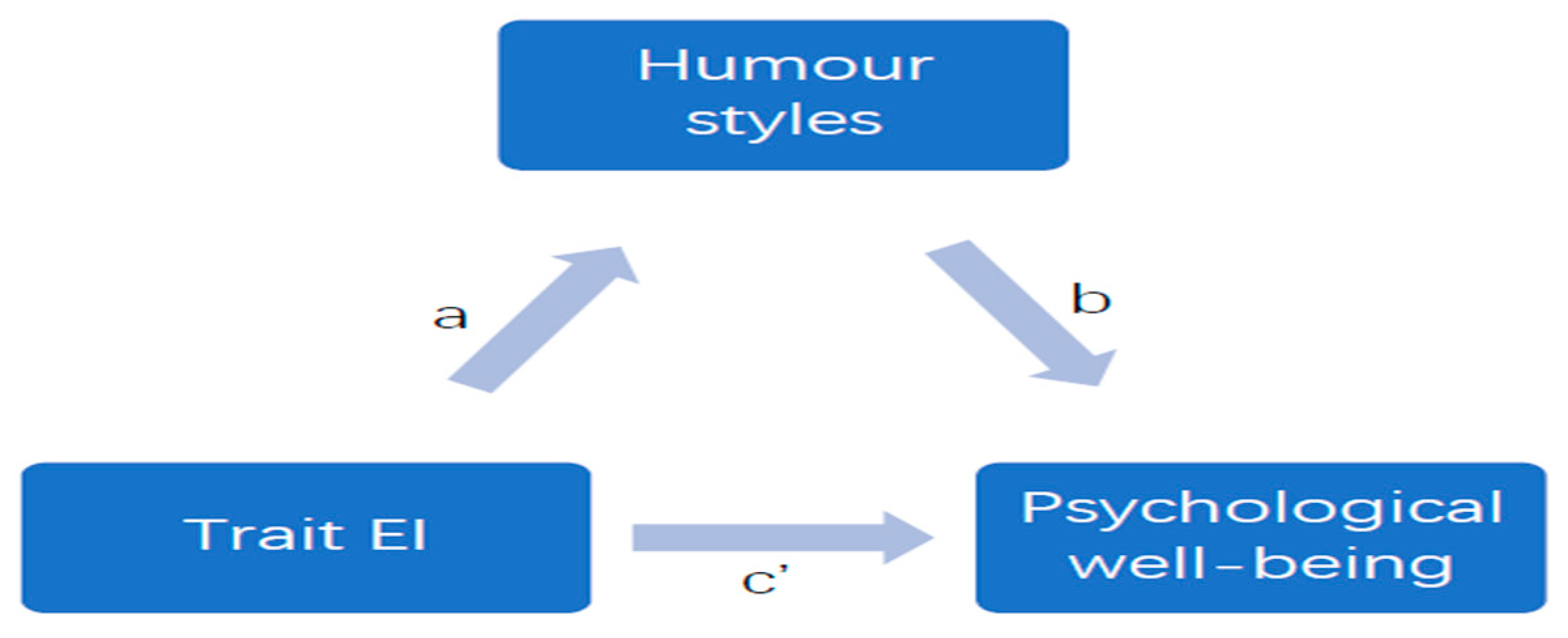

Psychological well-being is a sense of contentment and effective functioning free of suffering. Emotional intelligence (EI) comprises abilities in recognizing, interpreting, handling, and managing emotions (Xing, 2023). Many studies show a link between EI and mental wellness, yet the underlying processes remain debatable. One possible mediator in the relationship is humor(Xing, 2023). The part humor plays in the connection between EI and psychological well-being among college students was investigated in this systematic review and mixed methods research(Xing, 2023).

The systematic review investigated previously available data on the connection between EI and humour patterns. Ten studies' findings showed that EI was consistently and favourably related to adaptive humour techniques as well as negatively linked in certain studies to maladaptive comedy (Xing, 2023). Compared to ability EI (i. e. , perceiving EI as a cognitive skill), trait EI (i. e. , viewing EI as a personality feature) showed broader connections with humour styles(Xing, 2023). Self-enhancing humour—a humorous perspective and a coping strategy towards difficulty—demonstrated the most constant connection with both ability and trait EI (Xing, 2023). Trait EI evaluated with the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire revealed broad, and small to medium correlations with humour styles; this instrument was used for the quantitative investigation of the mediating influence of humour styles between trait EI and well-being, and distress(Xing, 2023).

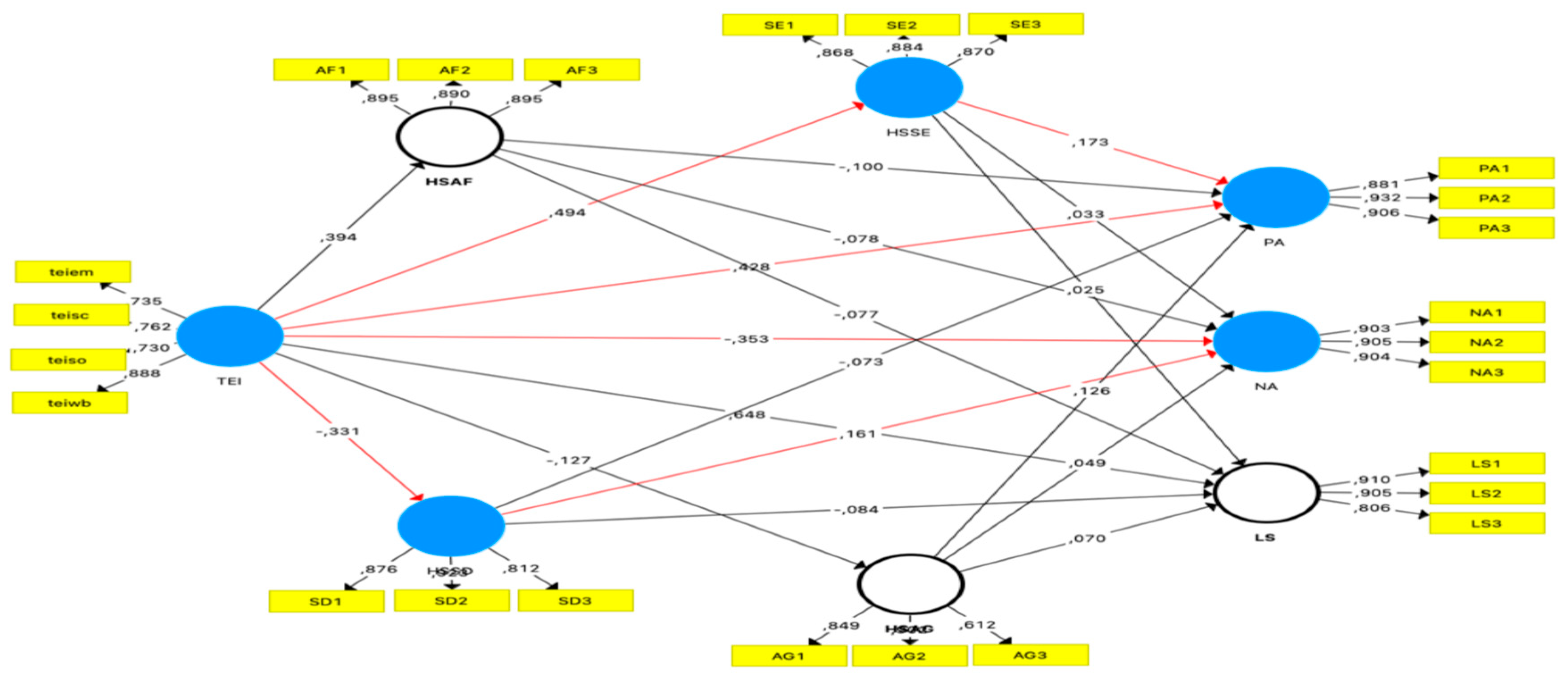

Partially least squares structural equation modelling (N = 536) found self-enhancing humour mediated the relationship between trait EI and positive affect; self-defeating humour (i. e. , amusing others at the expense of self) mediated the relationship between trait EI and negative affect, anxiety, and depression, separately; and affiliative humour (i.e., amusing others to improve relationships and reduce tensions) mediated the relationship between trait EI and anxiety. Qualitative semi-structured interviews (N = 16) investigated the role of humour in self-managing psychological well-being among UK/EU and international students with different degrees of EI(Xing, 2023).

Topics covered included significance of psychological well-being; uses of humour, and; self-managing psychological well-being (Xing, 2023). Supporting the theory in the Affective Mediation Model and suggesting possible treatments, humor styles are among the processes underlying the link between EI and psychological well-being(Xing, 2023).

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) is a statistical technique used to analyze complex relationships between variables(Xing, 2023), in this case, to explore how trait emotional intelligence (EI) affects psychological outcomes through different humor styles. The researchers created "parcels," which are groups of related survey items, to represent the different constructs being studied, like trait EI and psychological well-being(Xing, 2023). Mediation analysis was performed (Xing, 2023) to see how humor styles influence the relationship between trait EI and various psychological outcomes, using a method called bootstrapping to ensure the results were statistically significant.

An expert is someone who has dedicated significant time and effort to mastering a specific area of knowledge or skill, making them more proficient at solving related problems compared to novices, who are less experienced(Klein, 2023). Research shows that experts not only possess a greater depth of knowledge but also organize that knowledge in a more effective way, allowing them to recognize patterns and principles more easily(Klein,2023).

Additionally(Klein, 2023), experts tend to invest more time in analyzing problems, which contributes to their faster and more accurate solutions.

Figure 6 (c.f., Xing, 2023) presented the hypothesized model.

Self-enhancement comedy (95% (Confidence Interval(CI) = [. 035, . 137]) helped to define the link between trait EI and positive affect generally. Self-defeating comedy (95% CI = [-. 088, -. 024]) moderated the relationship between trait EI and negative affect. Link from trait EI to hedonic well-being was partially mediated by humour styles. The mediation model in its whole is shown in

Figure 7 (c. f. , Xing, 2023).

2.4. Sociocultural Aspects in the Classroom

humour helps to create social bonds and cultural identification (Shepard, 2019). Adding jokes with cultural relevance can help to foster diversity and awareness.

Empirical Evidence Supporting Humor in Mathematics Education (Le and Pham, 2025) Numerous studies have proven the benefits of humour in mathematics education.

-Generate maths jokes or puns to introduce and condense concepts(Csaba et al., 2022). Add fun activities including math games, puzzles, and competitions. Creation of a humorous friendly classroom(Geng et al., 2024). Cultivate a setting that is inclusive and respectful in humour. Inspire kids to create their own riddles and jokes(Sidekerskienė and Damaševičius, 2024). Incorporate curriculum-related visual comedy, cartoons, and memes.

- Include amusing stories or experiences about mathematical ideas.

- Create puns or math jokes to introduce and synthesize concepts. Include interesting events such math games, puzzles, and competitions(Mageed and Nazir, 2024; Mageed, 2023 a-f ; Mageed, 2025a-d).

Establishment of a classroom friendly to humor (Natalia et al., 2024)

- Create a setting where comedy is respectful and inclusive. Invite kids to create their own jokes and riddles. Insert visual humour, memes, and cartoons related to the curriculum.

3. Examples of Fun Activities(Willingham, 2021)

- "Math escape rooms" with amusing clues.

- "Number jokes" tournaments to generate interest.

- Illustrating difficult ideas with funny films or animations.

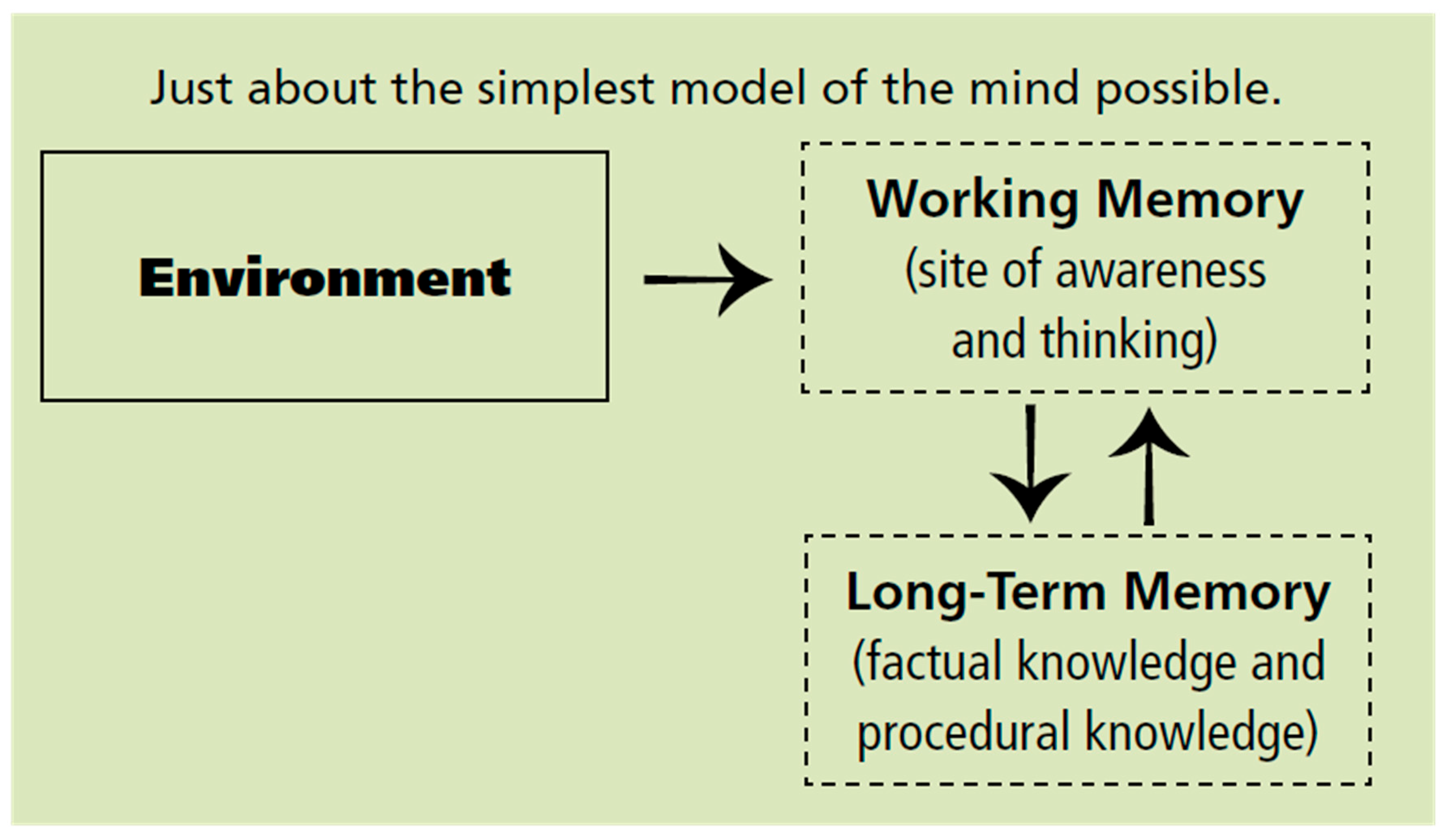

(Willingham, 2021) explored the challenges teachers face in making school enjoyable for students, highlighting that while people are naturally curious, they often struggle with thinking because it can be slow and difficult. When schoolwork is too challenging(Willingham, 2021), students may become frustrated and lose interest, making it harder for teachers to inspire them. Willingham (2021) suggested that teachers should rethink their approach to encourage effective thinking, which can lead to the satisfaction that comes from solving problems successfully.

Understanding the process of thinking(Willingham, 2021) is crucial because it reveals the factors that contribute to the difficulty of mental tasks. By recognizing what makes thinking challenging, educators can develop strategies to simplify these tasks for students (Willingham, 2021), making learning more enjoyable and effective. Ultimately, this approach can enhance students' engagement and success in school by aligning the difficulty of problems with their cognitive abilities, as illustrated by

Figure 8 (c.f., Willingham, 2021)

3.1. Obstacles and Factors of Note(Valeri, 2025)

- Make sure comedy is culturally sensitive and appropriate.

- To maintain academic standards, balance enjoyment and rigour.

- Recognising the various student sensitivities and humour preferences.

With research into the healing capacity of humor during cross-cultural acclimatation (Valeri, 2025), this thesis examines particular focus on foreign, professional soccer community members. Introduced through cooperation of scholarly research and the author's lived experiences(Valeri, 2025), the study helps to emphasize the dynamic role humour has in cultural adaptation and critical problems of comedy. Establishing researcher positionality and traversing strange and evolving cultural environments(Valeri, 2025). Inspired by Braidotti's theory of the nomadic subject, (Valeri, 2025) presented identity as a flexible, cyclic process of emerging through continuous experience inside changing, becoming that opposes established classification. contextual factors relating to culture and relationships Nomadism as entertainment examines the complex and evolving nature of identity(Valeri, 2025). Reflecting the challenges and opportunities that accompany negotiating unknown cultural surroundings, we bargain. our career life(Valeri, 2025). Employing hermeneutic phenomenology and advocacy ethnography, the research examines how cross-cultural adaptation uses comedy as both a bridge and a barrier(Valeri, 2025). Using a phenomenological technique and ethnographic protocol, the study gathers data especially, through team-building activities, training sessions, and games—triangulated analysis of miniature semi structured participant observations, focus groups, and interviews In the globally linked sports business of today, unique difficulties in changing across cultures could present professional football communities(Valeri, 2025). Through encouraging the possible worth of comedy, this study could offer priceless observations that could direct the developing better treatment approaches for people negotiating a globalized athletic terrain(Valeri, 2025).

3.2. Parallels Between Theory and Practice(Goos, 2020)

The theoretical foundations support the practical use of humour in mathematics education:

- Constructivism is consistent with activities that encourage learners to explore and generate humour, thereby promoting active knowledge construction.

- Cognitive Load Theory guides the timing and relevance of humour to promote learning without overload.

- The Affective Domain emphasises the value of happy feelings, which humour may uniquely foster.

- Social constructivism stresses the need of humor in creating classroom community and mutual understanding.

These similarities suggest that humour can be used as a pedagogical tool demonstrating basic educational ideas when deliberately included into training.