Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Details of the Model

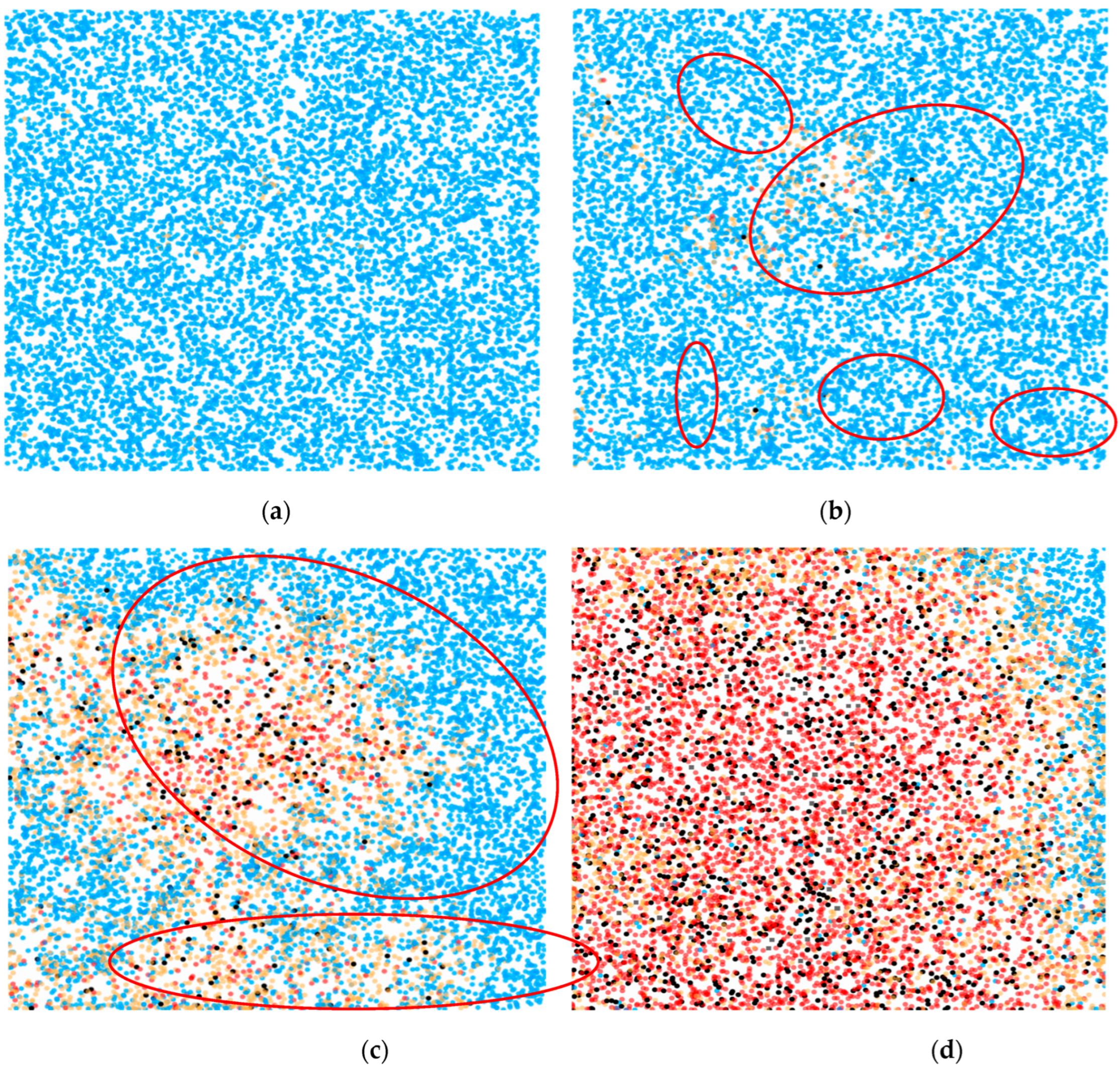

2.2. Definition of States in the Model

2.3. Dynamics of Transitions Between States

- Infection: Transition of agents from state to by contact with infected agents. The speed of this process depends on the frequency of contact and the probability of transmission:

- Recovery: Transition from to as infected agents recover. Rate of transition from to will be:

- Isolation: The transfer of agents from or to as a result of control measures such as contact tracing or isolation. Then the coefficient from to will be: . And from to will be: .

- Release from isolation: Return of agents from to (if they remain susceptible) or to (if recovered) after completion of the isolation period or confirmation of status by calculating: . From to (recovery in isolation): . From to will be: .

2.4. Impact on the Rate of Transmission of Infection

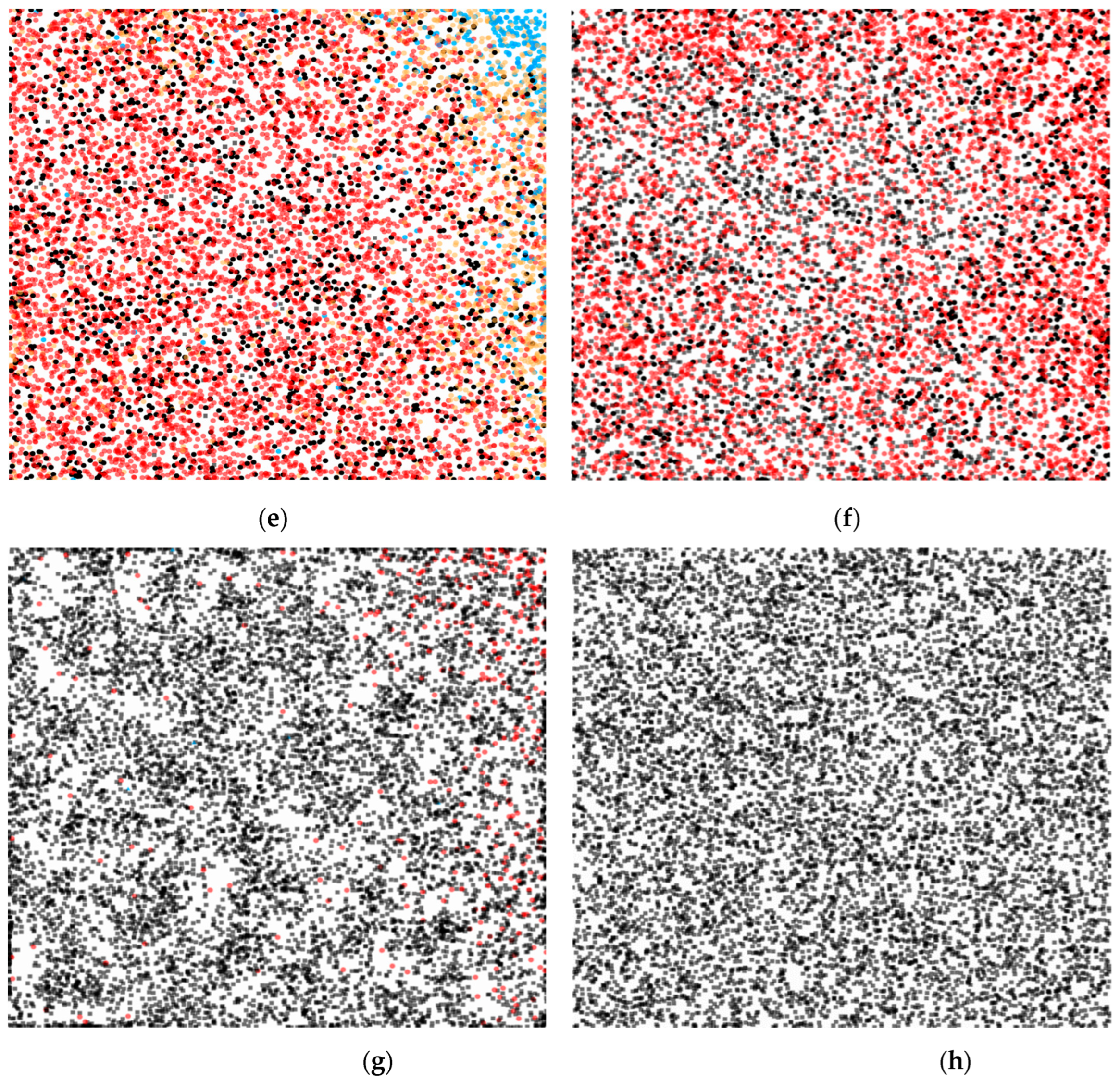

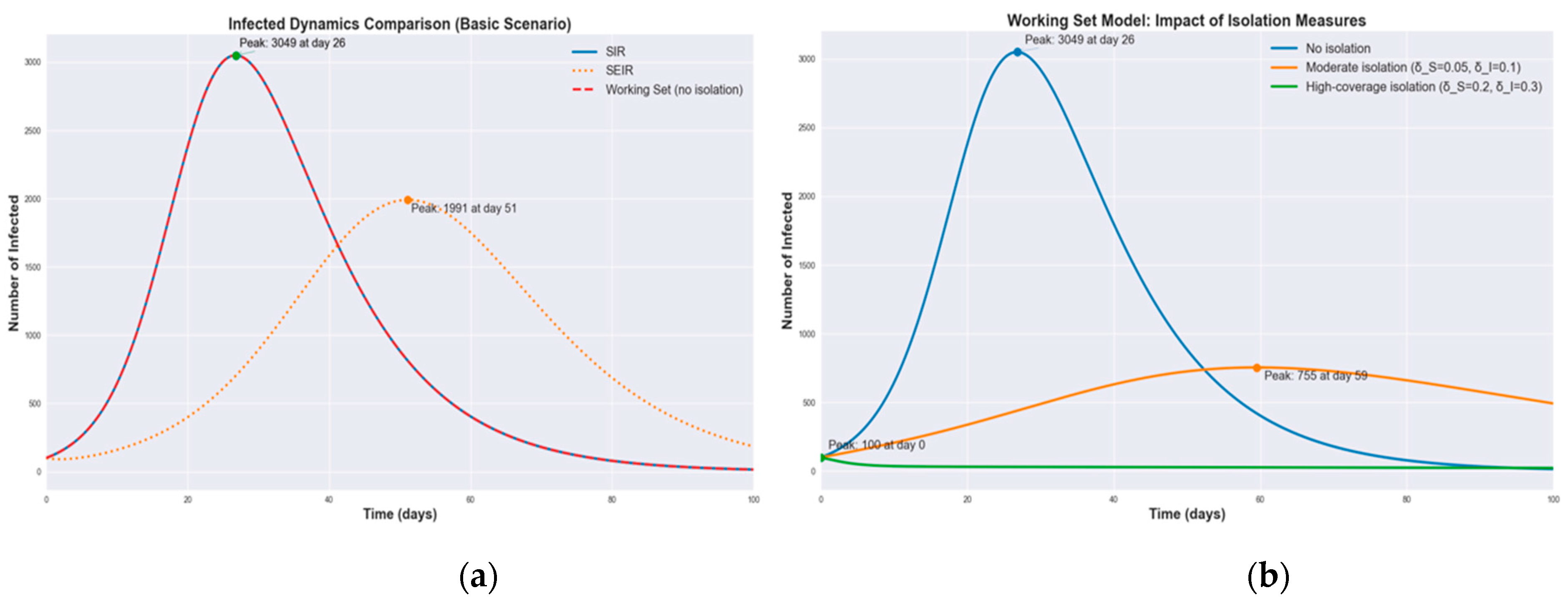

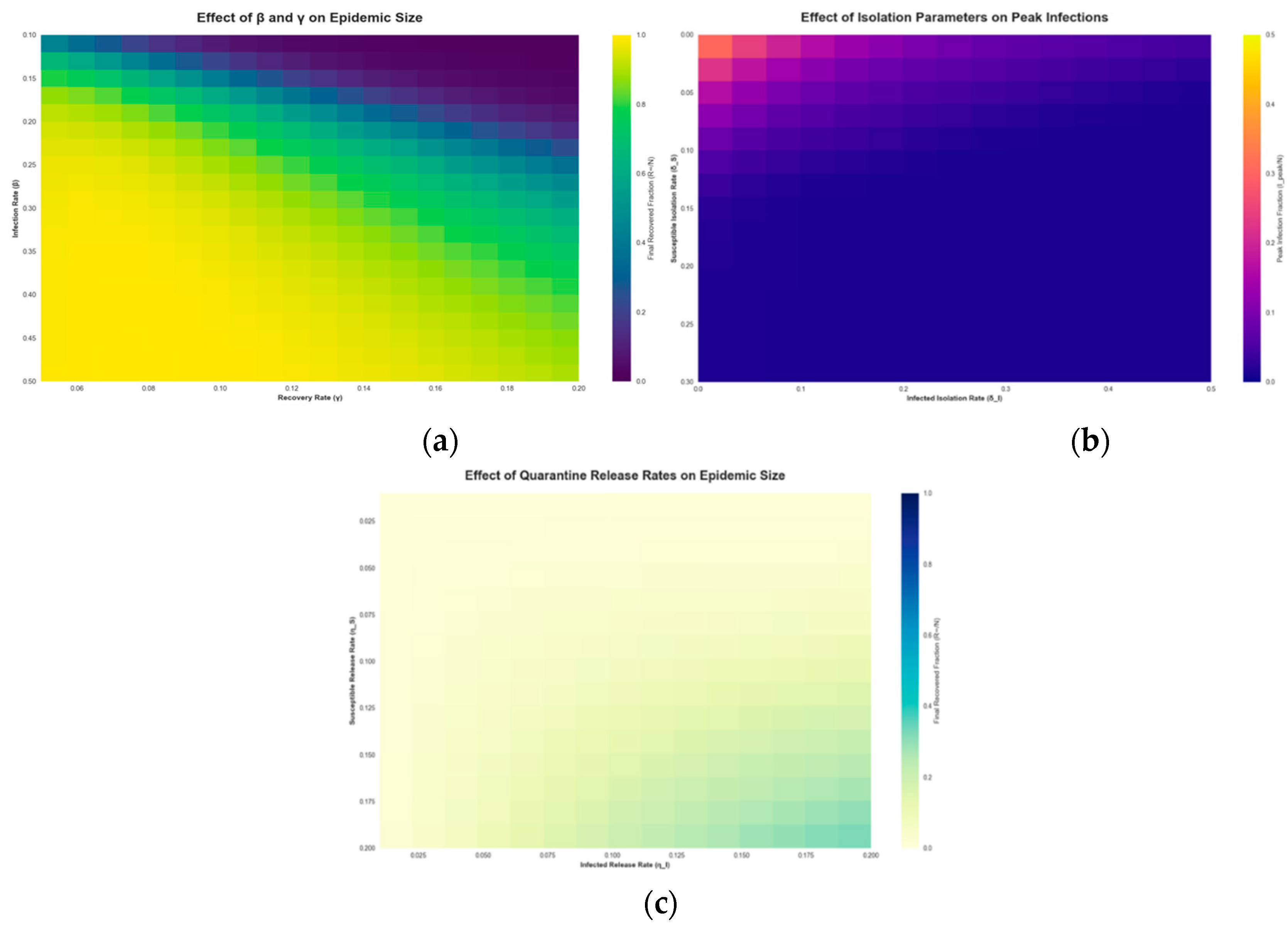

3. Modeling and Results

3.1. Numerical Simulations

| Aspect | SIR/SEIR | WS |

| Isolation | Not directly accounted, expansion required |

Included as centerpiece, dynamic adjustment |

| Transmission speed | Fixed or dependent on S and I | Dynamically adjusted based on active set |

| Contact heterogeneity | Requires extensions (e.g. network) | Accounting through groups and subsets |

| Behavioral solutions | Not modeled | May be enabled via agent rules |

| Applicability for interventions |

Limited without modifications | Easy to model isolation |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Billah, M.A.; Miah, M.M.; Khan, M.N. Reproductive Number of Coronavirus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Based on Global Level Evidence. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0242128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor-Satorras, R.; Castellano, C.; Van Mieghem, P.; Vespignani, A. Epidemic Processes in Complex Networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015, 87, 925–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hethcote, H.W. The Mathematics of Infectious Diseases. SIAM Rev. 2000, 42, 599–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegenfeld, A.F.; Kollepara, P.K.; Bar-Yam, Y. Modeling Complex Systems: A Case Study of Compartmental Models in Epidemiology. Complexity 2022, 2022, 3007864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermak, W.O; McKendrick, A.G. A Contribution to the Mathematical Theory of Epidemics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1927, 115, 700–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R. Global Stability of the Endemic Equilibrium of Multigroup SIR Models with Nonlinear Incidence. Computers & Mathematics with Applications 2010, 60, 2286–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkyilmazoglu, M. A Highly Accurate Peak Time Formula of Epidemic Outbreak from the SIR Model. Chinese Journal of Physics 2023, 84, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KhudaBukhsh, W.R.; Rempała, G.A. How to Correctly Fit an SIR Model to Data from an SEIR Model? Mathematical Biosciences 2024, 375, 109265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobeinikov, A. Global Properties of SIR and SEIR Epidemic Models with Multiple Parallel Infectious Stages. Bull. Math. Biol. 2009, 71, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Tuprio, E.P.D.; Estadilla, C.D.S.; Teng, T.R.Y.; Uyheng, J.; Estuar, M.R.J.E.; Espina, K.E.; Macalalag, J.M.R.; Sarmiento, R.F.R. Mathematical Analysis of a COVID-19 Compartmental Model with Interventions.; Penang, Malaysia, 2021; p. 020025.

- Gumel, A.B.; Iboi, E.A.; Ngonghala, C.N.; Elbasha, E.H. A Primer on Using Mathematics to Understand COVID-19 Dynamics: Modeling, Analysis and Simulations. Infectious Disease Modelling 2021, 6, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Chowell, G. Beyond the Initial Phase: Compartment Models for Disease Transmission. In Quantitative Methods for Investigating Infectious Disease Outbreaks; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; Volume 70, pp. 135–182. ISBN 9783030219222 9783030219239. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, J.A.L.; Gois, F.N.B.; Xavier-Neto, J.; Fong, S.J. Epidemiology Compartmental Models—SIR, SEIR, and SEIR with Intervention. In Predictive Models for Decision Support in the COVID-19 Crisis; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 15–39. ISBN 9783030619121. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Cai, Z.; Si, S.; Duan, D. Analysis of Epidemic Vaccination Strategies on Heterogeneous Networks: Based on SEIRV Model and Evolutionary Game. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2021, 403, 126172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safarishahrbijari, A.; Lawrence, T.; Lomotey, R.; Liu, J.; Waldner, C.; Osgood, N. Particle Filtering in a SEIRV Simulation Model of H1N1 Influenza. In Proceedings of the 2015 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC); December 2015; pp. 1240–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Bissett, K.R.; Cadena, J.; Khan, M.; Kuhlman, C.J. Agent-Based Computational Epidemiological Modeling. J Indian Inst Sci 2021, 101, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, F.A.; Moreno, U.F. A Multi-Agent-Based Simulation Model for the Spreading of Diseases Through Social Interactions During Pandemics. J Control Autom Electr Syst 2022, 33, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolles, J.; Luong, T. Modeling Epidemics With Compartmental Models. JAMA 2020, 323, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Andreasen, V.; Lloyd, A.; Pellis, L. Nine Challenges for Deterministic Epidemic Models. Epidemics 2015, 10, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givan, O.; Schwartz, N.; Cygelberg, A.; Stone, L. Predicting Epidemic Thresholds on Complex Networks: Limitations of Mean-Field Approaches. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2011, 288, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, A. What One Can Learn from the SIR Model. iascs 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džiugys, A.; Bieliūnas, M.; Skarbalius, G.; Misiulis, E.; Navakas, R. Simplified Model of Covid-19 Epidemic Prognosis under Quarantine and Estimation of Quarantine Effectiveness. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 140, 110162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, P. J. The working set model for program behavior, in Proceedings of the ACM symposium on Operating System Principles - SOSP ’67, Not Known: ACM Press, 1967, p. 15.1-15.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, P.J. Working Set Analytics. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 53, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Smith, J.O.; Schreiber, S.J.; Kopp, P.E.; Getz, W.M. Superspreading and the Effect of Individual Variation on Disease Emergence. Nature 2005, 438, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dénes, A.; Gumel, A.B. Modeling the Impact of Quarantine during an Outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease. Infect Dis Model 2019, 4, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poonia, R.C.; Saudagar, A.K.J.; Altameem, A.; Alkhathami, M.; Khan, M.B.; Hasanat, M.H.A. An Enhanced SEIR Model for Prediction of COVID-19 with Vaccination Effect. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, R.; Gnanaprakasam, A.J.; Boulaaras, S. Stability and Control Analysis of COVID-19 Spread in India Using SEIR Model. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 9095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, A.; Plank, M.J.; Hendy, S.; Binny, R.; Lustig, A.; Steyn, N.; Nesdale, A.; Verrall, A. Successful Contact Tracing Systems for COVID-19 Rely on Effective Quarantine and Isolation. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girvan, M.; Newman, M.E.J. Community Structure in Social and Biological Networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 7821–7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A.; Danon, L.; Diaz-Guilera, A.; Gleiser, P.M.; Guimer, R. Community Analysis in Social Networks. The European Physical Journal B - Condensed Matter 2004, 38, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayatifar, L.; Rigg, R.A.; Bar-Yam, Y.; Morales, A.J. US Social Fragmentation at Multiple Scales. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2019, 16, 20190509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, T.; Ball, F.; Trapman, P. A Mathematical Model Reveals the Influence of Population Heterogeneity on Herd Immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020, 369, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, W.; Jin, Z. How Heterogeneous Susceptibility and Recovery Rates Affect the Spread of Epidemics on Networks. Infectious Disease Modelling 2017, 2, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, R.I.; Roberts, M.G. How Population Heterogeneity in Susceptibility and Infectivity Influences Epidemic Dynamics. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2014, 350, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimov, A.; Lebedev, G.; Lebedev, M.; Semenycheva, I. COVID-19 Dynamics: A Heterogeneous Model. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 558368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolbeault, J.; Turinici, G. Social Heterogeneity and the COVID-19 Lockdown in a Multi-Group SEIR Model. Computational and Mathematical Biophysics 2021, 9, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Driessche, P.; Watmough, J. Reproduction Numbers and Sub-Threshold Endemic Equilibria for Compartmental Models of Disease Transmission. Mathematical Biosciences 2002, 180, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert-Dufresne, L.; Althouse, B.M.; Scarpino, S.V.; Allard, A. Beyond R0 : Heterogeneity in Secondary Infections and Probabilistic Epidemic Forecasting. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2020, 17, 20200393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, J.A.P.; Metz, J.A.J. On the Definition and the Computation of the Basic Reproduction Ratio R 0 in Models for Infectious Diseases in Heterogeneous Populations. J. Math. Biol. 1990, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topîrceanu, A. On the Impact of Quarantine Policies and Recurrence Rate in Epidemic Spreading Using a Spatial Agent-Based Model. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsukawa, Y.; Arefin, Md.R.; Kuga, K.; Tanimoto, J. An Agent-Based Nested Model Integrating within-Host and between-Host Mechanisms to Predict an Epidemic. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzsche, C.; Simm, S. Agent-Based Modeling to Estimate the Impact of Lockdown Scenarios and Events on a Pandemic Exemplified on SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 13391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluter, P.J.; Généreux, M.; Landaverde, E.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Hung, K.K.C.; Law, R.; Mok, C.P.Y.; Murray, V.; O’Sullivan, T.; Qadar, Z.; et al. An Eight Country Cross-Sectional Study of the Psychosocial Effects of COVID-19 Induced Quarantine and/or Isolation during the Pandemic. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 13175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, L.; Ouyang, H.; Zhan, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y. Behavioral Intentions and Perceived Stress under Isolated Environment. Brain and Behavior 2024, 14, e3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudriavtseva, A.S.; Arkadeva, O.G. IMPACT OF CORONAVIRUS (COVID-19) ON THE GLOBAL ECONOMY. Oecon. et jus 2022, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaka, W.; Lomwanawong, S.; Magel, D.; Maneejuk, P. Analysis of the Lockdown Effects on the Economy, Environment, and COVID-19 Spread: Lesson Learnt from a Global Pandemic in 2020. IJERPH 2022, 19, 12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Default value | Explanation |

|

|

10,000 | total number of agents in the population |

|

|

9970 | initial number of susceptible agents |

|

|

30 | initial number of infected agents |

|

|

0 | initial number of recovered agents |

|

|

0 | initial number of exposed agents (for SEIR model) |

|

|

0 | initial number of isolated susceptible agents |

|

|

0 | initial number of isolated infected agents |

|

|

0 | initial number of isolated recovered agents |

|

|

0.3 | infection rate; probability of disease transmission per contact between susceptible and infected agents |

|

|

0.3 | base infection rate for the working set |

|

|

0.2 | incubation rate; rate at which exposed agents become infectious (for SEIR model) |

|

|

0.1 | recovery rate; proportion of infected agents recovering per unit time |

|

|

0.1 | isolation release rate for susceptible agents; |

|

|

0.1 | isolation release rate for infected agents. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).