1. Introduction

Around the world, effective disease management is an essential part of public health and healthcare systems. In order to decrease the negative consequences infections have on patients, communities, and society at large, it encompasses a wide spectrum of prevention, management, and treatment methods. Enhancing health outcomes and reducing the burden of illness, from infectious diseases that can spread fast through populations to chronic illnesses that require ongoing care, depends on effective disease management [

12]. Disease management attempts to take preventive measures to stop the emergence and spread of diseases in addition to attending to the immediate medical needs of individuals who are afflicted. By focusing on prevention, early detection, and evidence-based treatments, disease management attempts to reduce healthcare costs, enhance quality of life, and promote overall wellbeing. Steps like contact tracing, isolation, vaccination and quarantine are routinely used in effective disease management for infectious diseases [

5,

6,

7,

8,

14,

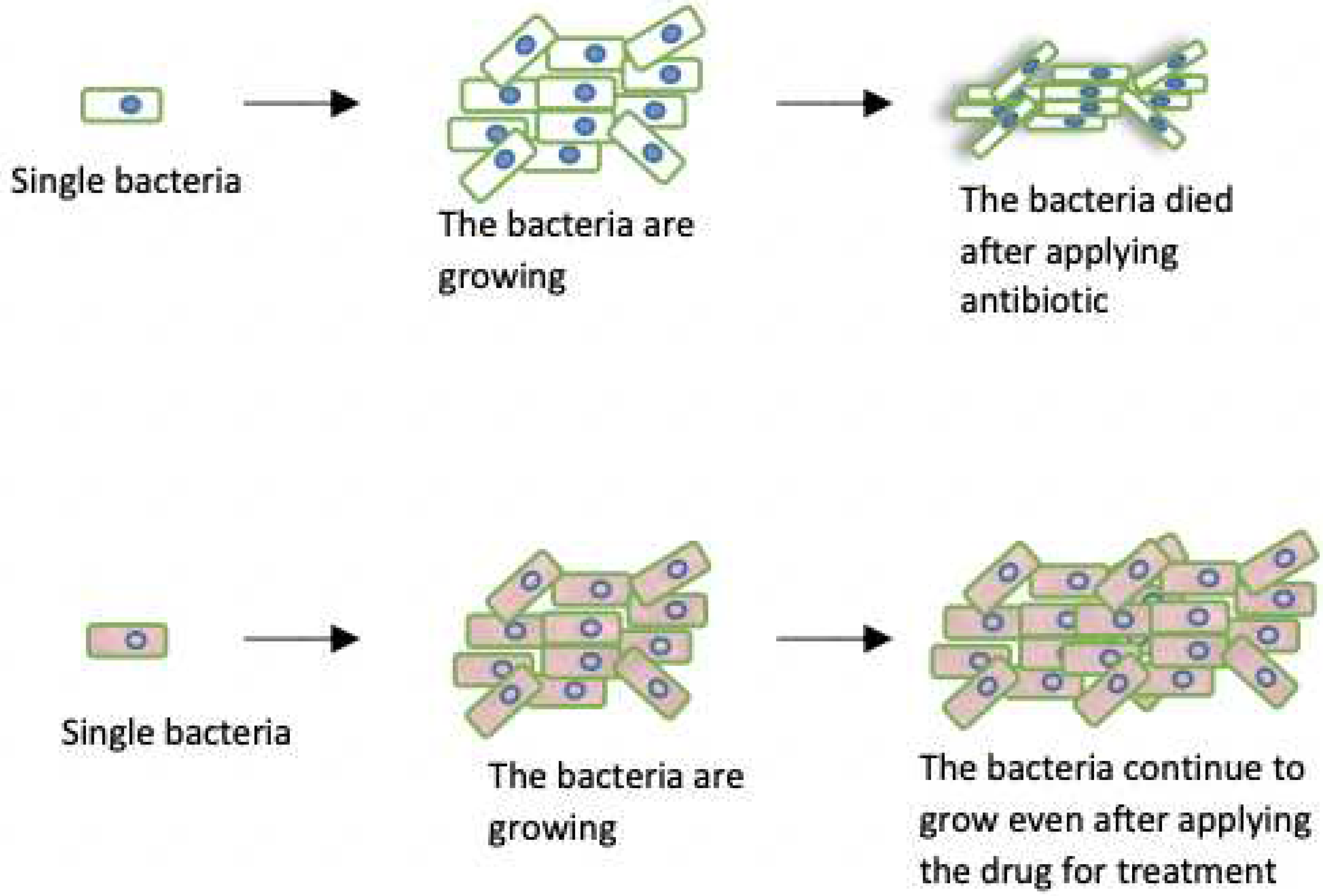

17]. By isolating sick people and monitoring their contacts, the disease’s spread can be managed, limiting further transmission within the population. A set of therapeutic suggestions based by empirical research and clinical investigations also forms the basis for disease management. Healthcare practitioners follow set standards to guarantee that patients receive the most effective and appropriate care for their condition. antibiotic stewardship is also emphasised in order to address the expanding problem of antibiotic resistance which is the genetic change that occurs within the bacteria which enables them to survive the application of antibiotic (

Figure 2) [

54] and maintain the effectiveness of crucial medicines. Recent advances in science and technology have accelerated efforts to treat illnesses. The improvement of disease diagnosis accuracy and therapeutic efficacy is facilitated by the introduction of novel drugs, preventative measures, and diagnostic tools. Strategies for managing diseases must be flexible and adaptable since diseases might evolve and new issues might surface. When healthcare systems can quickly adapt to changing situations, they can successfully manage both present and emerging health issues. We now explain in more depth what is quiescence state.

2. Quiescence State

Quiescence can be defined as a state of inactivity/dormancy that certain microorganisms, including viruses and bacteria, enter the body under some conditions. In this state, these microorganisms may be insensitive to antibiotics, making them difficult to be eradicated. This state of dormancy has significant implications for effective infectious diseases management as it can lead to persistent infections, recurrences, and treatment failures [

2,

3,

4]. Quiescence in viral infections happens when the virus becomes latent and inactive after integrating its genetic material into the Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of the host cell [

9,

13]. A virus can persist in this state for long periods of time (weeks, months, or even years), reactivating on some occasions and leading to illness relapses [

18,

19,

52,

53] see also (

Figure 1). (Please note that the

Quiescence is different from

Drug Resistance) in the case of drug resistance the bacteria is active while in the quiescent are not. The herpes simplex virus, the HIV virus, and the hepatitis B virus are a few examples of viruses that can enter quiescence. Similar to this, some bacteria, like Mycobacterium TB, have the ability to enter a phase called quiescence, during which they become less vulnerable to medications and the host immune system. The persistence of tuberculosis infections and the formation of drug-resistant strains are thought to be caused by this condition of dormancy. Additionally, millions of people die from the fatal illness of malaria each year [

19]. One of the five malaria parasites that cause the disease, Plasmodium, has a complicated life cycle that involves both mosquito and human hosts weeks, months, or even years may pass before the parasite reactivates and causes malaria symptoms in the liver cells [

20,

21]. It has been suggested that the characteristic of quiescence may be a means by which Plasmodium parasites elude the host immune response and survive in the liver cells [

23,

28,

39,

40]. Similar to this, developing successful treatment plans requires an understanding of the mechanisms underlying quiescence in viral disorders. Quiescence in different microorganisms is being studied by researchers to find strategies to prevent or disrupt this state and enhance the effectiveness of treatments[

32,

36,

45,

48]. Quiescence can help maintain population stability by building up a reservoir of dormant parasites among the host population [

3,

50]. There may be a mixture of parasites that are reproducing actively and parasites that are dormant in a typical parasite population [

36]. This variety of states ensures the parasite population’s longevity over time, especially in unfavorable circumstances such when receiving antibiotic therapy. Some members of the parasite population may go into a quiescent state when exposed to harmful conditions, such as antibiotic use [

51]. The parasites that are actively reproducing may be killed or inhibited by the antibiotic, but the quiescent parasites are left in a dormant, non-replicating state. When the antibiotic therapy is stopped or when circumstances are more conducive to reproduction, these dormant parasites may become active again. The parasite’s overall population size and genetic diversity are supported by this reservoir of dormant parasites [

9]. Quiescent parasites are less susceptible to the deadly effects of antibiotics than actively proliferating parasites are, despite the fact that medications may still have some effect on them. This is due to their decreased metabolic activity and replication rate. Due to this resistance, dormant parasites can endure antibiotic therapy and possibly reawaken when conditions are better. By assuming a quiescent condition, parasites are able to avoid the immediate threat of antibiotics and create long-term plans to combat them.It’s crucial to remember that the specific mechanisms and tactics used by parasites might change based on the host environment and the species of the parasite. One method parasites may use to increase their chances of survival and drug resistance is quiescence [

10]. The general insensitivity of parasite populations to antibiotics can also be caused by other causes, including genetic changes or the acquisition of resistance genes as defined above and shown in (

Figure 2). Quiescence can be a tactic used by parasites to increase population stability and build up drug resistance. Some parasites go into quiescence, which is characterised by decreased metabolic activity or a state of dormancy, when unfavourable conditions are present, such as when antibiotics are present or the host immune system is actively attacking them.

Figure 1.

Population of bacteria that started from one comprising of active (white) and quiescent (blue). After applying antibiotic the active cell died while the those that are in quiescent phase remain alive. When the antibiotic is taken away the quiescent cells woke up and continued to grow. As one can see some proportion of the bacteria became quiescent again, is rate rate at which the bacteria population become quiescence and is the rate of exiting quiescence, this stochastic process continues in this pattern.

Figure 1.

Population of bacteria that started from one comprising of active (white) and quiescent (blue). After applying antibiotic the active cell died while the those that are in quiescent phase remain alive. When the antibiotic is taken away the quiescent cells woke up and continued to grow. As one can see some proportion of the bacteria became quiescent again, is rate rate at which the bacteria population become quiescence and is the rate of exiting quiescence, this stochastic process continues in this pattern.

Figure 2.

Resistant and non-resistant populations of bacteria, the non-resistant bacteria died after applying antibiotic while resistant population did not.

Figure 2.

Resistant and non-resistant populations of bacteria, the non-resistant bacteria died after applying antibiotic while resistant population did not.

3. Disease Mechanisms

To comprehend the dynamics of quiescent parasite and foresee its effects for effective disease management measures, mathematical models are useful tools. The mechanisms driving parasite quiescence, however, are not well known, and the potential use of mathematical models to the study of quiescence has not been substantially investigated. Investigating the importance of mathematical models in comprehending the influence of quiescence in the co-infection model has been studied in [

1,

16,

25,

36]

4. The SIQR Model with Demography

A mathematical model called the Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered (SIR) model with demography studied in [

55,

56,

57] is used to analyse how infectious diseases propagate throughout a community. The SIR model becomes a more realistic and detailed representation of disease dynamics when demographic elements are added. In this Reseach work, we incooporate quiescence phase to SIR model using demographics and build up SIQR model with Demography.

Four compartments are created within a population by the SIQR model:

**Susceptible (S):** People who are not afflicted with the illness but are at risk of contracting it.

- -

**Infectious (I):** Those who have the illness and have the potential to transfer it to others.

- -

**Quiescence (Q):** Those who have the illness but the parasites are not active and therefore have no potential to transfer it to others.

- -

**Recovered (R):** People who are immune after recovering from the illness.

System of Ordinary Differential Equations

1 describe the rates of change people in each compartment over time and keep the record of transitions between these compartments. Within a population, demographic parameters take into account the rates of births and deaths. We add one more compartment to the SIR model when we incorporate Quiescence stage: The parameters of the models are:

representing the birth rate at which new individuals enter the population,

is the transmission rate,

is the recovery rate,

is the death rate,

is the rate of entering quiescence,

is the rate of exiting the quiescence phase and

N is the total population size.

Understanding the Formulas in model 1

Taking into consideration the effects of diseases, births, and deaths, the first equation shows the change in the susceptible population.

Taking infections, recoveries, and deaths into account, the second equation shows the shift in the infectious population.

When quiescence phase in put into consideration, the third equation shows the rate of change of quiescent population.

Fourth equation shows the change in the recovered population.

The SIQR model with demography, which takes mortality and population growth into account, offers a more thorough understanding of disease dynamics as most diseases exhibit some form of quiescence. In order to manage and mitigate the spread of infectious diseases within a population, this model assists policymakers in making better-informed decisions.

The Equilibrium Solutions

The equilibrium solution of a mathematical model represents a steady state where the system’s variables no longer change over time. The SIQR model has two equilibrium solutions , the first equilibrium solution occurs when the number of infectious, quiescence, and recovered individuals is zero and the number of susceptible individual is give as the ratio of birth and death rates, that is

The second equilibrium solution is the endemic equilibrium where the disease persists in the population, in the SIQR model, this happens when the individual in each compartment coexist and the equilibrium solution is given by

4.1. Stochasticity

Since our aim to to find the effect of quiescence on the mean number of infected individual, we now transform the model

1 into a stochastic process (birth and death process). We first find the transition probabilities give in

Table 1. The likelihood of changing from one state to another within a specified time frame (very small) is referred to as a transition probability. The dynamics of people moving over time between the four compartments (Susceptible, Infectious, Quiescence and Recovered) are captured by these transitions. The continuous time Markov Chain of SIQR model has the following transitions: from susceptible to infectious (caused by disease transmission), from infectious to recovered (caused by immunity or recovery), from infectious to quiescent stage (caused by parasite entering quiescence phase), from quiescent stage to infectious (caused by parasite exiting quiescence phase), the birth of susceptible into the population (caused by giving birth) and the death of individual from each compartment (caused by natural death or disease induced death). In this research research we find that the quiescence increases the mean number of infected individuals.

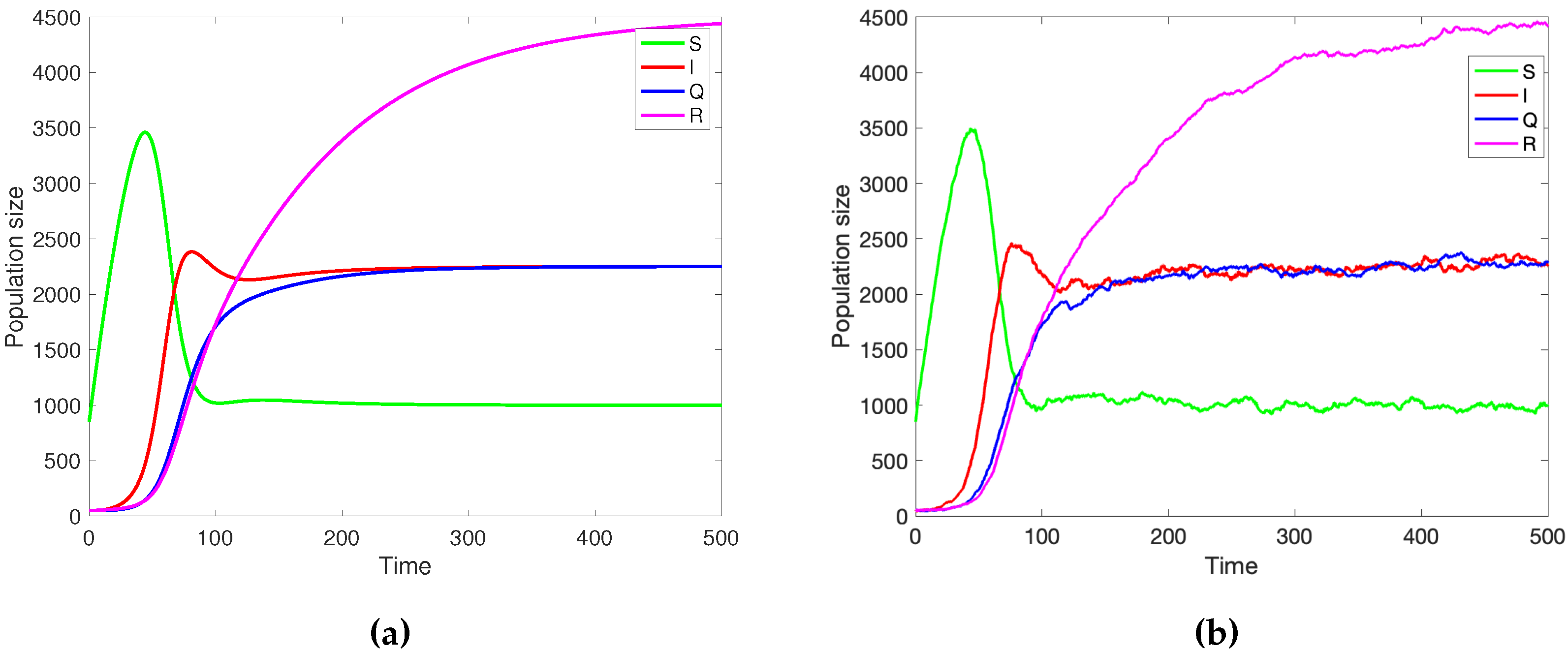

Figure 3.

a)Numerical simulation of the deterministic SIQR model

1 with

and the parameter values

b) Stochastic simulation of SIQR model using Gillespie’s algorithm; initial population size is

the parameters are

1 with the parameter values

Please observe that the stochastic and deterministic solutions are in good agreement.

Figure 3.

a)Numerical simulation of the deterministic SIQR model

1 with

and the parameter values

b) Stochastic simulation of SIQR model using Gillespie’s algorithm; initial population size is

the parameters are

1 with the parameter values

Please observe that the stochastic and deterministic solutions are in good agreement.

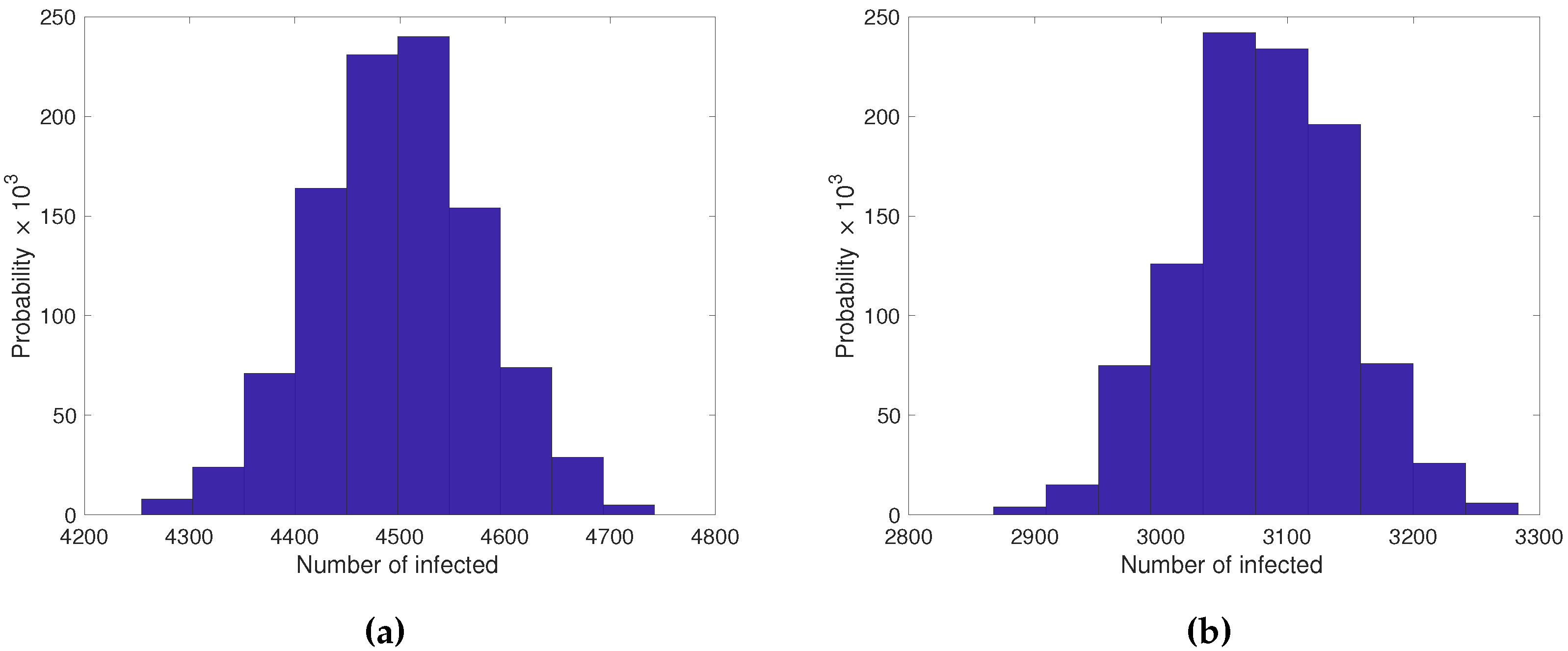

Figure 4.

a) Probability distribution of the number of infected of the stochastic SIQR model (1000 repetitions of Gillespie’s algorithm) with and the parameter values b) Probability distribution of the number of infected of the stochastic SIR model (1000 repetitions of Gillespie’s algorithm) with and the parameter values Please observe that the quiescence shifted the mean number of infected to the right.

Figure 4.

a) Probability distribution of the number of infected of the stochastic SIQR model (1000 repetitions of Gillespie’s algorithm) with and the parameter values b) Probability distribution of the number of infected of the stochastic SIR model (1000 repetitions of Gillespie’s algorithm) with and the parameter values Please observe that the quiescence shifted the mean number of infected to the right.

5. Management Approach

As these dormant organisms might contribute to the survival and return of the illness, managing infectious diseases under the influence of pathogen quiescent can be difficult. However, a number of techniques can lessen the effect of quiescence on illness management. Here are a few ideas:

Prolonged Treatment Period: Extend the time that antibiotics are administered in order to target both quiescent and actively proliferating parasites. Quiescent parasites have a lower metabolic rate and a slower rate of reproduction. Therefore treating them for a longer time is necessary to completely eradicate them. You have a better chance of getting rid of dormant parasites and keeping the illness from re-emerging if you stick with the antibiotic prescription for a long time.

Disrupt Quiescence: Conduct research and create tactics to particularly target and interrupt parasite quiescence. This could entail locating the substances or mechanisms that quiescence induction uses and creating medications that can obstruct them. The efficacy of antibiotic therapy can be increased, resulting in better illness management, by interfering with the ability of parasites to enter or maintain a quiescent state.

Host immunological Enhancement: To attack dormant parasites, strengthen the host immunological response. Quiescent parasites have decreased metabolic activity, but the immune system can still identify and attack them. Along with antibiotic treatment, strategies like immunomodulatory medicines or immune system-boosting therapies can help trigger the host immune response against dormant parasites.

6. Discussion

Impact on Transmission: Since quiescence raises the average number of infected people, it stands to reason that less activity during this time could, paradoxically, accelerate the disease’s spread. There are a few possible causes for this phenomenon:

Reservoir Effect: Infectious agents may persist in spreading throughout a population if people are not actively practising prevention during the quiescent phase, which could result in a higher rate of infections when activity picks back up.

Altered Contact Patterns: Social interactions and contact patterns may be altered as a result of quiescence. Resuming regular activities without taking the necessary safety precautions may lead to an increase in the spread of disease.

Loss of Immunity: The population may become more vulnerable to the disease, which could contribute to an increase in infections, if the quiescent period results in a loss of acquired immunity or a drop in vaccination efficacy.

Implications for Public Health: It is crucial for public health to comprehend how diseases spread during times of quiescence. It highlights the necessity of focused interventions and communication tactics during these times to reduce the possibility of an increase in infections once regular operations resume.

7. Conclusion

It is important to note that the particular tactics used can change depending on the infectious condition at hand as well as the traits of the quiescent parasites involved. Therefore, it is crucial to adjust the management strategy to the unique features of the disease and take into account the most recent research findings and therapeutic recommendations. Overall, prevention, early detection, evidence-based therapy, teamwork, and innovation are all essential components of an effective disease management strategy. By putting these principles into practise, public health authorities and healthcare professionals can significantly advance efforts to lower illness incidence, enhance patient outcomes, and protect population health and well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, US, SS; methodology, US and SA; analysis, US ; investigation, US, SS and SA; writing—original draft preparation, US and SA; writing—review and editing, SA and US. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Karl, P. H. Topics in Mathematical Biology. 1st ed; Springer Cham: Springer Intertanational Publisher 2017; pp. 1–68.

- Lennon, Jay T. and Jones, Stuart E. Microbial seed banks: the ecological and evolutionary implications of dormancy. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 2011, 9, 1119–130.

- Blath, Jochen and Hermann, Felix and Slowik, Martin. A branching process model for dormancy and seed banks in randomly fluctuating environments. Journal of Mathematical Biology 2019, 83, 17. [Google Scholar]

- João, H. P. João, H. P. The impact of dormancy on evolutionary branching. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.01792 2022.

- Richard A., J.; Dean W., W. Dynamics of the 2001 UK foot and mouth epidemic: stochastic dispersal in a heterogeneous landscape. Science 2001, 294, 813–817. [Google Scholar]

- Balmer, O.; Tanner, M. The control of bovine viral diarrhoea virus in Europe: today and in the future. Plurithematic issue of the Scientific and technical review. 2006, 961–979. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani, S. Early clinical pathologists: Edward Jenner (1749-1823). Journal of clinical pathology 1992, 45, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, S. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 2005, 18, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaban, N.; Merrin, J.; Chait, R.; Kowalik, L.; Leibler, S. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 2004, 304, 1622–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrell, I; White, A. ; Pedersen, A. B. ; Hails, R. S.; Boots, M. The evolution of covert, silent infection as a parasite strategy. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 2009, 276, 2217–2226.

- Verin, M.; Tellier, A. Host-parasite coevolution can promote the evolution of seed banking as a bet-hedging strategy. Evolution 2018, 72, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, M. J.; Rohani, P. Modeling infectious diseases in humans and animals. Princeton University Press 2011.

- Kloehn, J.; Boughton, B. A.; Saunders, E. C.; O’Callaghan, S.; Binger, K. J.; McConville, M. J. Identification of metabolically quiescent Leishmania mexicana parasites in peripheral and cured dermal granulomas using stable isotope tracing imaging mass spectrometry. MBio 2021, 12, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L. J. An introduction to stochastic processes with applications to biology. Allen 2010, 12, 10–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K. Persister cells. Annual review of microbiology 2010, 64, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellinger, T.; Müller, J.; Hösel, V.; Tellier, A. Are the better cooperators dormant or quiescent? Mathematical biosciences 2019, 318, 108272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K. Exact and approximate formulas for contact tracing on random trees. Mathematical biosciencesy 2020, 321, 108320. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Francis EG History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors. Parasites & vectors 2010, 3, 1–9.

- Gural, N; Mancio-Silva, L; Miller, A. B.; Galstian, A.; Butty, V. L.; Levine, S. S.; Patrapuvich, R.; Desai, S. P.; Mikolajczak, S. A.; Kappe, S.H.; others In vitro culture, drug sensitivity, and transcriptome of Plasmodium vivax hypnozoites. Cell host & microbe 2018, 23, 395–406.

- Sato, S. Plasmodium—a brief introduction to the parasites causing human malaria and their basic biology. Journal of physiological anthropology 2021, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, Robert W and Guerra, Carlos A and Noor, Abdisalan M and Myint, Hla Y and Hay, Simon I The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 2005, 434, 214–217. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. M.; May, R. M. Infectious diseases of humans: dynamics and control. Oxford university press 1992.

- Battle, K. E; Gething, P. W.; Elyazar, I. R.; Moyes, C.L. ; Sinka, M. E.; Howes, R. E.; Guerra, C. A.; Price, R. N. ; Baird, J. K.; Hay, S.I. The global public health significance of Plasmodium vivax. Advances in parasitology 2012, 80, 1–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hairston Jr, N. G.; De Stasio Jr, B. T. Rate of evolution slowed by a dormant propagule pool. Advances in parasitology 1998, 336, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, B.; Müller, J.; Tellier, A.; Živković, D. Fisher–Wright model with deterministic seed bank and selection. Theoretical Population Biology 2017, 336, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, Alan R and Levin, Donald A Evolutionary consequences of seed pools. The American Naturalist 1979, 114, 232–249. [CrossRef]

- Cox, F. E. History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors. Parasites & vectors 2010, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Thida and Aung, Aye Aye and Raksapraidee, Rattanaporn and Carrara, Verena I and Bancone, Germana and Watson, James and others Comparison of the cumulative efficacy and safety of chloroquine, artesunate, and chloroquine-primaquine in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018, 67, 1543–1549.

- Maslov, S.; Sneppen, K. Well-temperate phage: optimal bet-hedging against local environmental collapses. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, J. T; Jones, S. E. Microbial seed banks: the ecological and evolutionary implications of dormancy. Nature reviews microbiology 2011, 9, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, C. T; Hu, P. J. Insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling in C. elegans. WormBook: The Online Review of C. elegans Biology [Internet] 2018, 9, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, C. T; Hu, P. J. What is bet-hedging? Oxford surveys in evolutionary biology 1987, 4, 182–211. [Google Scholar]

- Blath, Jochen and Hermann, Felix and Slowik, Martin A branching process model for dormancy and seed banks in randomly fluctuating environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.06393 2020.

- Coates, Anthony RM. Dormancy and low growth states in microbial disease. WormBook: The Online Review of C. elegans Biology [Internet] 2003, 3.

- Cohen, N. R;Lobritz, M. A.; Collins, J. J. Microbial persistence and the road to drug resistance. host & microbe 2013, 13, 632–642. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, S and Sona, J. ; Johannes, M.; Aurélien, T. Quiescence generates moving average in a stochastic epidemiological model with one host and two parasites. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2289.

- Wood, T. K.; Knabel, S. J.; Kwan, B. W. Bacterial persister cell formation and dormancy. Applied and environmental microbiology 2013, 79, 7116–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, M.; Christina, K. Methods and models in mathematical biology. Lecture Notes on Mathematical Modelling in the Life Sciences, Springer, Heidelberg, Germany 2015.

- Robinson, Leanne J and Wampfler, Rahel and Betuela, Inoni and Karl, Stephan and White, Michael T and Li Wai Suen, Connie SN and Hofmann, Natalie E and Kinboro, Benson and Waltmann, Andreea and Brewster, Jessica and others Strategies for understanding and reducing the Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale hypnozoite reservoir in Papua New Guinean children: a randomised placebo-controlled trial and mathematical model. PLoS medicine 2015, 12, e1001891.

- Taylor, Aimee R and Watson, James A and Chu, Cindy S and Puaprasert, Kanokpich and Duanguppama, Jureeporn and Day, Nicholas PJ and Nosten, Francois and Neafsey, Daniel E and Buckee, Caroline O and Imwong, Mallika and others Resolving the cause of recurrent Plasmodium vivax malaria probabilistically. PLoS medicine 2019, 10, 5595.

- Gural, Nil and Mancio-Silva, Liliana and Miller, Alex B and Galstian, Ani and Butty, Vincent L and Levine, Stuart S and Patrapuvich, Rapatbhorn and Desai, Salil P and Mikolajczak, Sebastian A and Kappe, Stefan HI and others In vitro culture, drug sensitivity, and transcriptome of Plasmodium vivax hypnozoites. Cell host & microbe 2018, 23, 395–406.

- White, N. J. Determinants of relapse periodicity in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Malaria journal 2011, 10, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A. R.; Watson, J. A.; Chu, C. S.; Puaprasert, K.; Duanguppama, J.; Day, N. P.; Nosten, F.; Neafsey, D. E.; Buckee, C. O.; Imwong, M. ; others. Resolving the cause of recurrent Plasmodium vivax malaria probabilistically. Nature communications 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Cindy S and Phyo, Aung Pyae and Turner, Claudia and Win, Htun Htun and Poe, Naw Pet and Yotyingaphiram, Widi and Thinraow, Suradet and Wilairisak, Pornpimon and Raksapraidee, Rattanaporn and Carrara, Verena I and others. Chloroquine versus dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine with standard high-dose primaquine given either for 7 days or 14 days in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019, 68, 1311–1319.

- Wood, T. K.; Knabel, S. J.; Kwan, B. W. Bacterial persister cell formation and dormancy. Applied and environmental microbiology 2013, 79, 7116–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blath, J.; Tóbiás, A. Invasion and fixation of microbial dormancy traits under competitive pressure. Stochastic Processes and their Applications 2020, 130, 7363–7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, M. A.; Zhang, C.; Whitaker, R. J. Virus-induced dormancy in the archaeon Sulfolobus islandicus. MBio 2015, 130, e02565–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, M. A.; Zhang, C.; Whitaker, R. J. Dormancy and low growth states in microbial disease. MBio 2003, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Blath, J.; Tóbiás, A. Blath, J. ; Tóbiás, A. Virus dynamics in the presence of contact-mediated host dormancy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.11242 2021.

- Tellier, Aurélien Virus dynamics in the presence of contact-mediated host dormancy. New Phytologist 2019, 221, 725–730.

- Sorrell, Ian and White, Andrew and Pedersen, Amy B and Hails, Rosemary S and Boots, Mike The evolution of covert, silent infection as a parasite strategy. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2009, 276, 2217–2226. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, Pintu and Klumpp, Stefan Population dynamics of bacterial persistence. PLoS One 2013, 8, e62814.

- Patra, Pintu and Klumpp, Stefan Bacterial persistence: Fundamentals and clinical importance. Journal of Microbiology 2019, 57, 829–835. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Causes of Antimicrobial (Drug) Resistance. Journal of Microbiology, Online; last accessed on 04-August-2023 2023,.

- Keeling, Matt J. and Rohani, Pejman Modeling Infectious Diseases in Humans and Animals. Princeton University Press 2008.

- Bartlett, M Deterministic and stochastic models for recurrent epidemics, Vol. 4. PLoS One 1956.

- Bartlett, M. S. The critical community size for measles in the United States. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society 1960, 123, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).