As tree roots elongate and increase in diameter, they must generate sufficient pressure to displace the surrounding soil (Reichert et al., 2021). This pressure is limited both by the ability of root cells to exert force through turgor pressure (Azam, 2013) and by the root’s capacity to generate a reactionary force. Without this reactionary force, the root may be pushed backward instead of extending further into the soil (Eavis, 1967). To counteract this, root hairs help anchor the root and prevent backward movement. In compacted soils, root hairs become both longer and more abundant. Under extreme compaction, roots often increase in diameter due to their heightened sensitivity to axial rather than radial pressure (Tomobe et al., 2023; Bengough, 2012). Consequently, it is believed that constraints on radial expansion may actually promote axial elongation, enabling roots to grow more effectively through dense soils (Bengough & Mullins, 1991; Eavis, 1967).

While radial root growth can generate higher pressures than axial growth, it is still ultimately constrained. In an early study, Zwieniecki and Newton (1995) split rock profiles to examine morphological changes in roots growing within narrow fissures. When growth was restricted in two directions, the root cortex became severely deformed, adopting a wing-like shape, while the stele remained cylindrical and unaffected by the surrounding environment. This morphological plasticity was observed only in certain species. Local conifers such as Pinus ponderosa (Dougl. ex Laws.) and Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) did not produce roots in the most confined spaces.

Understanding the mechanical limits of axial and radial root growth has both ecological and practical implications. From an ecological perspective, researchers have studied these limits to better understand plant colonization and soil development in compacted and confined rooting environments (Bello-Bello et al., 2022). From an applied perspective, these thresholds have been examined to project yield in traditional forest management (Reichert et al. 2021) and address infrastructure conflicts in urban forest environments (Grabosky et al. 2011).

While axial root growth has been more commonly studied (Bengough & Mullins, 1991; Atwell, 1993; Clark et al., 2003), fewer investigations have examined the pressures generated by radial root growth (Potocka and Szymanowska-Pułka 2018; Tracy et al., 2011). In an early experiment, Misra et al. (1986) tested whether radial expansion of pea, cotton, and sunflower seedling roots could generate enough pressure to break surrounding chalk walls of varying thicknesses. This work was later supported by Kolb et al. (2012), who directed emerging chickpea radicles between pairs of photoelastic discs to assess the radial forces exerted along the sides of the root.

Studies of the pressures associated with radial root growth in mature woody roots are even more limited than those focused on seedlings. Grabosky et al. (2011) examined roots that had grown between two layers of foam placed beneath a sidewalk over a ten-year period. To estimate the pressure exerted by the roots, they recreated the observed indentations using a press and measured the resulting stress with a load cell.

Our objective was to determine the limits of radial root expansion in woody roots. While advancing understanding of woody root development, this also holds practical implications for engineers seeking to prevent pavement lifting in urban areas—a costly ecosystem disservice. As noted by Zwieniecki and Newton (1995), extremely confining rooting environments can alter root morphology, flattening roots where they exceed radial expansion thresholds. Although Misra et al. (1986) addressed this question in seedling roots of non-woody species, and Grabosky et al. (2011) focused on woody roots, the latter did not explore this threshold. Identifying such a threshold could help engineers design urban infrastructure that resists cracking or lifting and encourages root flattening—a more desirable alternative to root loss from infrastructure repair or replacement.

To determine the limits of radial expansion in woody roots, we applied mechanical constraints to 30 roots each of Quercus virginiana and Taxodium distichum. Roots were located using an air excavator and fitted with custom clamps with elastic bands that exerted increasing radial pressure as growth progressed. Flattening—indicative of anisotropic growth restriction—was monitored over time. Once observed, roots were excised, and stress at the point of deformation was calculated. Trials began with Q. virginiana in March 2023 and expanded to T. distichum in November 2023, concluding for both species in December 2024. Logistic regression was used to model root flattening given species and stress during the study period.

Mean initial diameter for Quercus virginiana roots was 32.00 mm (SD = 11.38), with values ranging from 10.08 mm to 52.28 mm. Taxodium distichum roots were smaller on average, with a mean diameter of 19.55 mm (SD = 8.79) and a range of 5.38 mm to 35.86 mm. One oak root was excluded due to clamp failure during the study period. Additionally, three T. distichum roots were not harvested at the conclusion of the study because they began producing knees within the airspace of the observation boxes. These roots were preserved in situ for continued monitoring using time-lapse photography. In total, eight of the 30 T. distichum roots developed knees in the airspace adjacent to the clamps. This supports early observations by Whitford (1956), who noted that knees were more likely to form in areas with greater aeration compared to the rest of the root zone.

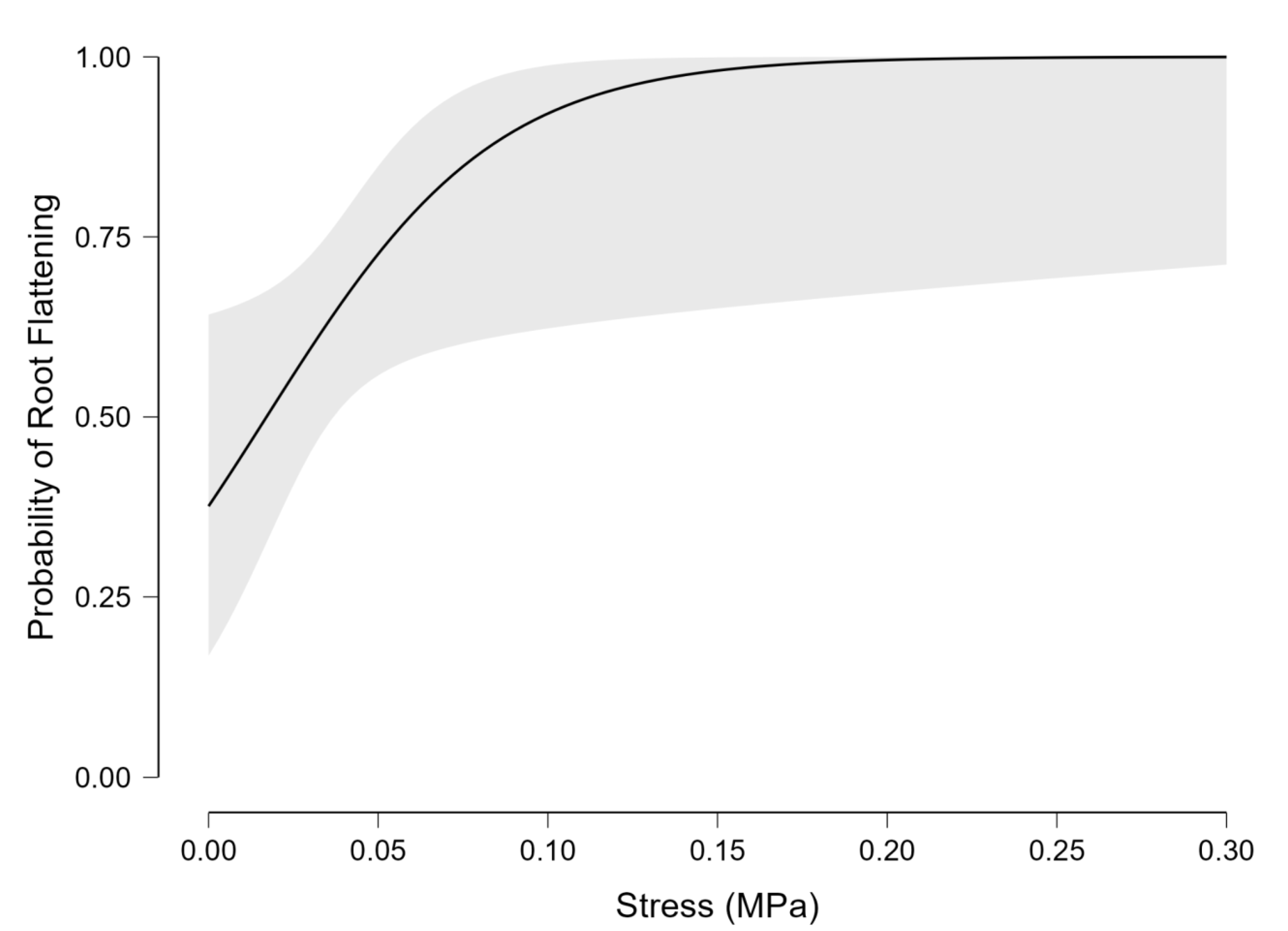

At the conclusion of the study, 36 roots had exhibited flattening, while 20 had not. Initial logistic regression models included both species and applied stress (MPa) as predictors of root flattening. However, species was not a significant predictor (P = 0.139) and was removed from the final model (

Table 1). The simplified model using stress alone showed a statistically significant relationship with root flattening (P = 0.038). Model performance metrics included an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.696 and a Nagelkerke R² of 0.144. The overall classification accuracy was 71.43%, with better performance in identifying flattened roots (88.89%) than non-flattened roots (40.00%).

The prediction curve from our logistic regression model (

Figure 1) was used to estimate the stress required to trigger root flattening at increasing levels of confidence. The goal of this analysis was to determine the stress level at which all roots could be expected to flatten. However, because the logistic function approaches but never actually reaches 100%, we used values very close to 100% to estimate this upper threshold. A stress of 0.173 MPa corresponded to a 99% likelihood of flattening, while 0.251 MPa was needed for 99.9%, and 0.329 MPa for 99.99%.

Our estimated stress thresholds for root flattening (0.173 to 0.329 MPa) fall within the lower to middle range of values reported in other studies (

Table 1). Compared to previous work on seedling radicles, our results are lower than the 0.50 MPa threshold observed by Misra et al. (1986) for

Pisum sativum, but overlap with thresholds reported for

Gossypium hirsutum (0.29 MPa) and

Helianthus annuus (0.24 MPa). They also align closely with the values observed in

Cicer arietinum (0.30 ± 0.15 MPa) by Kolb et al. (2012). Relative to other studies of woody roots, our values are slightly lower than those reported by Grabosky et al. (2011) for

Platanus ×

hispanica (0.35–0.40 MPa), potentially reflecting species differences or the longer time frame over which stress accumulated in our study.

This study provides one of the first empirical estimates of the pressure threshold at which mature woody roots begin to deform in response to radial constraint. By quantifying the stress required to induce root flattening in Quercus virginiana and Taxodium distichum, we contribute to a growing body of work aimed at understanding root biomechanics under confining soil conditions. Our results suggest that root deformation occurs at relatively modest pressures, particularly compared to values reported for seedling radicles or larger woody roots in different settings. These findings have practical implications for infrastructure design, particularly in the context of mitigating root-related pavement damage which is a significant and costly ecosystem disservice (Roman et al. 2021). Future work should explore how species, soil type, and duration of constraint influence these thresholds, and whether roots subjected to moderate pressure can be directed to flatten without compromising tree health or stability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded through the Florida Chapter of the International Society of Arboriculture’s research and education grant program. We thank Hunter Thorn, Elise Willis, and Zachary Freeman for their early work setting up the experiment.

References

- Atwell, B.J. Response of roots to mechanical impedance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1993, 33, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, G.; Grant, C.D.; Misra, R.K.; Murray, R.S.; Nuberg, I.K. Growth of tree roots in hostile soil: A comparison of root growth pressures of tree seedlings with peas. Plant Soil 2013, 368, 569–580. [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Bello, E.; López-Arredondo, D.; Rico-Chambrón, T.Y.; Herrera-Estrella, L. Conquering compacted soils: uncovering the molecular components of root soil penetration. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 814–827. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bengough, A.G. Root elongation is restricted by axial, but not radial pressures: so what happens in field soil? Plant Soil 2012, 360, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bengough, A.G.; Mullins, C.E. Penetrometer resistance, root penetration resistance and root elongation rate in two sandy loam soils. Plant Soil 1991, 131, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.J.; Whalley, W.R.; Barraclough, P.B. How do roots penetrate strong soil? Plant Soil 2003, 255, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Eavis, B.W. Mechanical impedance to root growth. In Agricultural Engineering Symposium, Silsoe 1967, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Grabosky, J.; Smiley, E.T.; Dahle, G.A. Research note: Observed symmetry and force of Platanus X acerifolia (Ait.) Wild. roots occurring between foam layers under pavement. Arbor. Urban For. 2011, 37, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, E.; Hartmann, C.; Genet, P. Radial force development during root growth measured by photoelasticity. Plant Soil 2012, 360, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, R.K.; Dexter, A.R.; Alston, A.M. Maximum axial and radial growth pressures of plant roots. Plant Soil 1986, 95, 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Potocka, I.; Szymanowska-Pulka, J. Morphological responses of plant roots to mechanical stress. Ann. Bot. 2018, 122, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reichert, J.M.; Morales, C.A.; de Bastos, F.; Sampietro, J.A.; Cavalli, J.P.; de Araújo, E.F.; Srinivasan, R. Tillage recommendation for commercial forest production: Should tillage be based on soil penetrability, bulk density or more complex, integrative properties? Geoderma Regional. 2021, 25, e00381. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, L.A.; et al. Beyond ‘trees are good’: Disservices, management costs, and tradeoffs in urban forestry. Ambio 2021, 50, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tomobe, H.; Tsugawa, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Arita, T.; Tsai, A.Y.-L.; Kubo, M.; Demura, T.; Sawa, S. A mechanical theory of competition between plant root growth and soil pressure reveals a potential mechanism of root penetration. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7473. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.R.; Black, C.R.; Roberts, J.A.; Mooney, S. J. Soil compaction: a review of past and present techniques for investigating effects on root growth. J Sci Food Agric 2011, 91, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whitford, L.A. A theory on the formation of cypress knees. J. Mitchell Soc. 1956, 72, 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zwieniecki, M.A.; Newton, M. Roots growing in rock fissures: their morphological adaptation. Plant Soil 1995, 172, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).