Submitted:

05 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: Establishing the Context and Rationale

1.1. The Broader Landscape: Background and Significance

1.2. The Core Problem: Identifying the Critical Gap or Controversy

1.3. Delineating the Review’s Focus and Approach

1.4. A Roadmap for the Reader: Structure of the Article

2. Thematic Synthesis and Critical Analysis of the Literature

2.1. Historical and Conceptual Foundations

2.1.1. The Genesis of the Field: Seminal Works and Key Milestones

2.1.2. The Evolution of Core Concepts and Theories

2.2. The Methodological Canvas: Approaches to Research in the Field

2.2.1. Predominant Research Methodologies: A Critical Overview

- Case Studies: Case studies provide in-depth analyses of specific AI applications, offering rich, contextual insights into their integration with scientific workflows. A prominent example is DeepMind’s AlphaFold, which solved the protein folding problem with unprecedented accuracy, demonstrating AI’s capacity to address complex scientific challenges (Jumper et al., 2021). Another significant case is the development of DSP-1181, the first AI-designed drug to enter clinical trials, created through a collaboration between Exscientia and Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma for obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment. This project completed its exploratory research phase in under 12 months, compared to the traditional 4-6 years, showcasing AI’s potential to accelerate drug discovery (Burki, 2020). These cases highlight AI’s role in generating and testing hypotheses, aligning with the principles of Generative Metascience.

- Experimental Studies: Experimental studies compare AI-driven methods with traditional approaches, providing rigorous evidence of AI’s efficacy. For instance, Granda et al. (2018) demonstrated that AI-optimized chemical reaction conditions outperformed human-designed methods, achieving higher efficiency in organic synthesis (Granda et al., 2018). Such studies validate AI’s practical utility in scientific tasks, supporting its role as a generative tool in research.

- Surveys and Interviews: These methods capture scientists’ perceptions of AI, revealing adoption barriers such as lack of training or concerns about model transparency. A survey by the Center for Science, Technology and Environmental Policy Studies at Arizona State University found that while scientists recognize AI’s potential to enhance research, many express concerns about its impact on scientific integrity and the need for ethical guidelines (Z. Chen et al., 2024). Similarly, a Pew Research Center survey reported that 52% of Americans are more concerned than excited about AI’s role in daily life, reflecting broader societal apprehensions that influence scientific adoption (Zhang & Dafoe, 2019).

- Data Mining and Bibliometric Analyses: These approaches identify trends in AI’s application across disciplines by analyzing large datasets of publications. Rahman et al. (2024) conducted a bibliometric analysis of AI in medical diagnoses, noting a significant increase in machine learning and deep learning usage as such, underscoring AI’s growing influence (Rahman et al., 2024). These analyses provide a macro-level perspective on AI’s integration into scientific research.

- Simulations: Simulations test AI in virtual environments, offering cost-effective ways to evaluate its predictive capabilities. Raccuglia et al. (2016) used machine learning to simulate and accelerate the discovery of new materials, demonstrating AI’s ability to explore complex systems where physical experiments are impractical (Raccuglia et al., 2016). Such simulations support hypothesis generation, a key aspect of Generative Metascience.

- Theoretical Modeling: Theoretical models develop frameworks to understand AI’s role in science. Jordan and Mitchell (2015) proposed a model for how AI can reshape hypothesis generation and testing, providing a conceptual foundation for studying AI’s impact on scientific discovery (Jordan & Mitchell, 2015). These models guide empirical research but require validation to ensure practical relevance.

2.2.2. Strengths, Weaknesses, and the Rise of Innovative Methods

Critical Analysis of Methodological Blind Spots

Emerging Innovative Methods

2.3. Thematic Deep Dive 1

2.3.1. Synthesis of Key Findings and Supporting Evidence

2.3.2. Areas of Consensus and Controversy

- Interpretability: Deep learning models often operate as “black boxes,” delivering accurate predictions without transparent decision-making processes. This opacity is problematic in fields like medical research, where mechanistic understanding is essential for trust and validation (Obermeyer et al., 2019). In contrast, some argue that high accuracy, such as in galaxy classification, may suffice when categorization is the primary goal (Banerji et al., 2012).

- Data Quality and Bias: AI’s effectiveness depends on training data quality. In genomics, datasets skewed toward European ancestry can produce biased models, risking health disparities (Popejoy & Fullerton, 2016). Debates center on whether technical solutions like debiasing algorithms or inclusive data collection are more effective.

- Overreliance on AI: While AI streamlines research, overreliance without human oversight may lead to “illusions of understanding,” where researchers misinterpret AI outputs (Topol, 2019). Some view AI as a tool to enhance creativity, while others caution it could undermine scientific rigor.

- Ethical Concerns: Data privacy, especially in genomics, raises significant issues. Balancing AI-driven insights with privacy protection requires robust ethical guidelines to maintain public trust (Jobin et al., 2019).

2.3.3. Critique of the Literature and Methodological Limitations

2.4. Thematic Deep Dive 2

2.4.1. Synthesis

2.4.2. Controversy

2.4.3. Critique

- Dataset Limitations: Many studies rely on narrow datasets, limiting generalizability. For example, in materials science, AI models trained on specific material types may not apply broadly, necessitating more diverse datasets. For example, one AI-driven screen predicted a novel antibiotic candidate, but follow-up laboratory assays revealed it had no measurable antimicrobial activity. This false lead underscores the indispensability of empirical validation in AI-generated hypotheses.

- Interpretability Challenges: The “black box” nature of AI models hinders validation, particularly in hypothesis-driven research. Emerging explainable AI methods like SHAP and LIME show promise, but further development is needed (Lundberg et al., 2022).

- Lack of Standardized Metrics: Evaluating AI-generated hypotheses lacks standardized metrics. Current benchmarks, like the DREAM Challenges for drug discovery, focus on predictive accuracy rather than novelty (Prill et al., 2010). In materials science, the Materials Project evaluates properties but not innovativeness (Jain et al., 2013). Novel metrics, possibly from information theory, are needed to assess hypothesis originality. For instance, approaches based on information theory, such as measuring the Kullback-Leibler divergence between predicted and observed outcomes, offer potential ways to assess the surprisal or innovativeness of AI proposals (Foster et al., 2021). However, these methods are still in early stages and require further development to be widely applicable in scientific contexts.

- Data Bias: Studies often rely on datasets with inherent biases, leading to hypotheses that amplify these flaws. In healthcare, AI trained on specific populations may produce hypotheses less applicable to underrepresented groups (Parikh et al., 2019).

- Privacy Concerns: Fields like genomics and social sciences involve sensitive data, raising privacy issues. Compliance with ethical standards and data protection regulations is essential (Jobin et al., 2019).

- Societal Implications: In areas like criminal justice, AI-generated hypotheses can impact society broadly, as seen in the judicial study, necessitating fairness and accountability (Ludwig & Mullainathan, 2024). Addressing these requires inclusive data practices, transparency, and adherence to guidelines like those from the IEEE (Zhao et al., 2020).

- Integration with Traditional Practices: AI-generated hypotheses require rigorous experimental validation. Open science practices, such as sharing models and datasets, are crucial for transparency and reproducibility. Crucially, human oversight remains indispensable in this process. While AI can propose hypotheses, human researchers must evaluate their plausibility and interpret results, as seen in the development of the AI-designed drug DSP-1181, where human experts guided validation and clinical trials (Burki, 2020).

- Longitudinal Studies: Few studies evaluate the long-term impact of AI-generated hypotheses. Future research should prioritize real-world validations, novel metrics, interpretability advancements, and ethical compliance to ensure AI’s responsible application in science.

2.5. Cross-Thematic Analysis: Interconnections and Contrasting Perspectives

Defining Generative Metascience

Interconnections: The Iterative Cycle of Data and Hypotheses

Contrasting Objectives and Evaluation Metrics

-

Objectives:

- o

- Theme A aims for precision in quantifying known patterns, such as classifying galaxies or identifying genetic variants (Davis & Goadrich, 2006).

- o

- Theme B seeks novelty, proposing uncharted research directions, such as predicting cancer recurrence based on gland morphology (Bulten et al., 2022).

-

Evaluation Metrics:

- o

- Theme A uses quantitative metrics like accuracy and precision, as seen in exoplanet detection with 96% accuracy (Jin et al., 2022; Valizadegan et al., 2022).

- o

- Theme B requires experimental validation, which is inherently uncertain and long-term, as in the A-Lab’s material synthesis (Banerjee et al., 2025).

The Paradigm of Algorithmic Discovery

3. Discussion, Implications, and Future Trajectories

3.1. Integrated Summary of Key Insights

3.2. Unanswered Questions and Gaps in the Literature

3.3. Implications for Theory and Practice

3.4. Recommendations for Future Research

- Explainable AI (XAI): Develop domain-specific XAI methods, building on tools like SHAP and LIME from section 2.4, to enhance transparency (Lundberg et al., 2022).

- Inclusive Datasets: Compile diverse datasets to reduce biases in genomics and social sciences, as seen in Theme A (Popejoy & Fullerton, 2016).

- Standardized Metrics: Establish benchmarks to evaluate hypothesis generation, drawing from Theme B’s novelty needs (Prill et al., 2010).

- Long-Term Priorities:

- Longitudinal Studies: Assess AI’s sustained impact on productivity, extending Theme B’s real-world applications.

- Ethical Frameworks: Develop guidelines for fairness and privacy, addressing concerns from section 2.3 (Alvarez et al., 2024).

- Human-AI Collaboration: Optimize workflows by integrating AI with human expertise, enhancing Theme A and B synergy.

Appendix A: Literature Search and Selection Methodology

A.1 Search Strategy

A.1.1 Databases Queried

A.1.2 Search Terms and Strings

- General AI terms: “artificial intelligence,” “machine learning,” “deep learning,” “neural networks,” “generative AI”

- Science and metascience terms: “scientific discovery,” “metascience,” “algorithmic discovery,” “data analysis,” “hypothesis generation,” “experiment design”

- Specific applications and milestones: “AlphaFold,” “DENDRAL,” “AI in astronomy,” “AI in genomics,” “AI in materials science,” “AI in particle physics,” “AI in drug discovery”

- (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND (“scientific discovery” OR “metascience” OR “algorithmic discovery”)

- (“AI” OR “artificial intelligence”) AND (“data analysis” OR “hypothesis generation” OR “experiment design”) AND (“science” OR “research”)

- (“AlphaFold” OR “DENDRAL”) AND (“scientific discovery” OR “AI in science”)

A.1.3 Supplementary Search Methods

- Citation Tracking: Reference lists of key papers, such as those on AlphaFold (Nature) and DENDRAL (Wikipedia), were reviewed to identify additional relevant studies.

- Expert Consultations: Discussions with researchers in AI and metascience helped identify emerging works not yet indexed in databases.

- Conference Proceedings: Key conferences, such as NeurIPS, ICML, and AAAI, were reviewed for recent advancements in AI-driven scientific research.

A.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Publication Type: Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, or reputable preprints from platforms like arXiv.

- Time Frame: Published between 1960 and 2025 to capture the historical and contemporary scope of AI in science.

- Language: Primarily English, with exceptions for seminal non-English works with significant impact.

- Relevance: Directly addressed AI applications in scientific discovery, including data collection and analysis, hypothesis generation, experiment design, or metascience.

- Content: Provided empirical evidence, theoretical frameworks, or critical analyses relevant to the review’s objectives, such as AI’s methodological implications or ethical considerations.

A.2.2 Exclusion Criteria

- Were not in English, unless they were landmark publications.

- Consisted of grey literature, such as blog posts, news articles, or non-academic reports, unless they provided unique insights into recent developments (e.g., X posts on AI Scientist (Forbes)).

- Did not focus on AI applications in scientific contexts, such as purely technical AI papers without scientific applications.

- Were duplicates of already included studies.

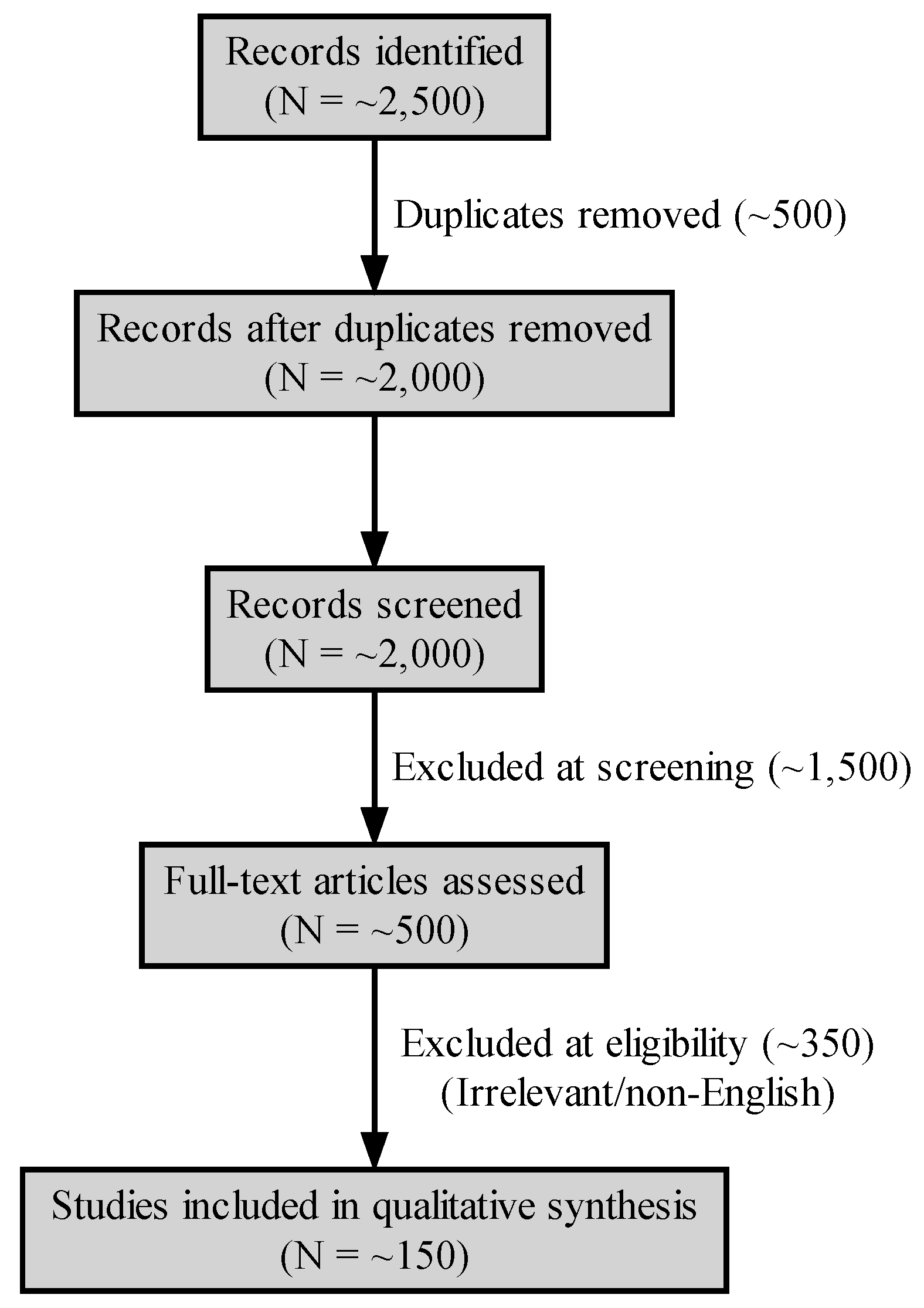

A.3 Study Selection Process

A.4 PRISMA Flow Diagram

A.5 Data Extraction

- AI Techniques: Specific methods used, such as neural networks, support vector machines, or generative models.

- Scientific Domains: Fields of application, including astronomy, genomics, materials science, and particle physics.

- Outcomes: Key findings, such as improved accuracy, novel discoveries, or accelerated research processes.

- Challenges: Reported limitations, such as model interpretability, data quality, or ethical concerns.

- Methodological Insights: Research methods employed, such as case studies, experimental studies, or bibliometric analyses.

A.6 Quality Assessment

A.7 Notes on Replicability

References

- Alvarez, J. M.; Colmenarejo, A. B.; Elobaid, A.; Fabbrizzi, S.; Fahimi, M.; Ferrara, A.; Ghodsi, S.; Mougan, C.; Papageorgiou, I.; Reyero, P.; Russo, M.; Scott, K. M.; State, L.; Zhao, X.; Ruggieri, S. Policy advice and best practices on bias and fairness in AI. Ethics and Information Technology 2024, 26(2), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, G.; Larson, E. C.; Mahoney, J. T. Thomas Kuhn on Paradigms. Production and Operations Management 2020, 29(7), 1650–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, P.; Brunak, S. Bioinformatics: The machine learning approach; MIT press, 2001; https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=pxSM7R1sdeQC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=Bioinformatics+and+Machine+Learning&ots=SOIDKb-01s&sig=P8WiT5bPP3wf8ZTw5SBCgQJpA9g.

- Ball, N. M.; Brunner, R. J. DATA MINING AND MACHINE LEARNING IN ASTRONOMY. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2010, 19(07), 1049–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Meng, Y. S.; Minor, A. M.; Zhang, M.; Zaluzec, N. J.; Chan, M. K. Y.; Seidler, G.; McComb, D. W.; Agar, J.; Mukherjee, P. P.; Melot, B.; Chapman, K.; Guiton, B. S.; Klie, R. F.; McCue, I. D.; Voyles, P. M.; Robertson, I.; Li, L.; Chi, M.; Brown, C. M. Materials laboratories of the future for alloys, amorphous, and composite materials. MRS Bulletin 2025, 50(2), 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, M.; McMahon, R. G.; Hewett, P. C.; Alaghband-Zadeh, S.; Gonzalez-Solares, E.; Venemans, B. P.; Hawthorn, M. J. Heavily reddened quasars at z 2 in the UKIDSS Large Area Survey: A transitional phase in AGN evolution. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2012, 427(3), 2275–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, M. A. Artificial intelligence; Elsevier, 1996; https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=_ixmRlL9jcIC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Boden,+1990+AI&ots=JROE-VoxRX&sig=LXNOgCnfLlgYp4X2RvynQJYRlq0.

- Bornmann, L.; Haunschild, R.; Mutz, R. Growth rates of modern science: A latent piecewise growth curve approach to model publication numbers from established and new literature databases. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2021, 8(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B. G.; Feigenbaum, E. A. DENDRAL and Meta-DENDRAL: Their applications dimension. In Readings in artificial intelligence; Elsevier, 1981; pp. 313–322. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978093461303350026X.

- Bulten, W.; Kartasalo, K.; Chen, P.-H. C.; Ström, P.; Pinckaers, H.; Nagpal, K.; Cai, Y.; Steiner, D. F.; Van Boven, H.; Vink, R. Artificial intelligence for diagnosis and Gleason grading of prostate cancer: The PANDA challenge. Nature Medicine 2022a, 28(1), 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulten, W.; Kartasalo, K.; Chen, P.-H. C.; Ström, P.; Pinckaers, H.; Nagpal, K.; Cai, Y.; Steiner, D. F.; Van Boven, H.; Vink, R. Artificial intelligence for diagnosis and Gleason grading of prostate cancer: The PANDA challenge. Nature Medicine 2022b, 28(1), 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. A new paradigm for drug development. The Lancet Digital Health 2020, 2(5), e226–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Nguyen, D. T.; Lee, S. J.; Baker, N. A.; Karakoti, A. S.; Lauw, L.; Owen, C.; Mueller, K. T.; Bilodeau, B. A.; Murugesan, V.; Troyer, M. Accelerating Computational Materials Discovery with Machine Learning and Cloud High-Performance Computing: From Large-Scale Screening to Experimental Validation. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2024, 146(29), 20009–20018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Yang, G.; He, X.; Chi, X.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, X. Research integrity in the era of artificial intelligence: Challenges and responses. Medicine 2024, 103(27), e38811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaboration, A. ATLAS data quality operations and performance for 2015-2018 data-taking. Journal of Instrumentation 2020, 15(04), P04003–P04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, C. M. S. Electron and photon reconstruction and identification with the CMS experiment at the CERN LHC. Journal of Instrumentation 2021, 16(05), P05014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Goadrich, M. The relationship between Precision-Recall and ROC curves. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning-ICML ’06; 2006; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. G.; Shi, F.; Evans, J. Surprise! Measuring novelty as expectation violation. 2021. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/2t46f/.

- Granda, J. M.; Donina, L.; Dragone, V.; Long, D.-L.; Cronin, L. Controlling an organic synthesis robot with machine learning to search for new reactivity. Nature 2018, 559(7714), 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haibe-Kains, B.; Adam, G. A.; Hosny, A.; Khodakarami, F.; Cesare 42, M. A. Q. C.(MAQC) S. B. of D. S. T. 35 K. R. 36 S. S.-A. 37 T. W. 35 W. R. D. 38 M. C. E. 39 J. W. 40 D. J. 41 F; Waldron, L.; Wang, B.; McIntosh, C.; Goldenberg, A.; Kundaje, A. Transparency and reproducibility in artificial intelligence. Nature 2020, 586(7829), E14–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, M. G.; Pantanowitz, L.; Jackson, B.; Palmer, O.; Visweswaran, S.; Pantanowitz, J.; Deebajah, M.; Rashidi, H. H. Ethical and bias considerations in artificial intelligence/machine learning. Modern Pathology 2025, 38(3), 100686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, S.; Shah, P.; Antony, B.; Hu, J. Artificial intelligence for clinical trial design. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2019, 40(8), 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iten, R.; Metger, T.; Wilming, H.; Del Rio, L.; Renner, R. Discovering Physical Concepts with Neural Networks. Physical Review Letters 2020, 124(1), 010508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, K.; Panagiotopoulou, S. K.; McRae, J. F.; Darbandi, S. F.; Knowles, D.; Li, Y. I.; Kosmicki, J. A.; Arbelaez, J.; Cui, W.; Schwartz, G. B. Predicting splicing from primary sequence with deep learning. Cell 2019, 176(3), 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S. P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W. D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Materials 2013, 1(1). https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apm/article/1/1/011002/119685. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yang, L.; Chiang, C.-E. Identifying Exoplanets with Machine Learning Methods: A Preliminary Study. International Journal on Cybernetics & Informatics 2022, 11(2), 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobin, A.; Ienca, M.; Vayena, E. The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nature Machine Intelligence 2019, 1(9), 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M. I.; Mitchell, T. M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015a, 349(6245), 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M. I.; Mitchell, T. M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015b, 349(6245), 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, P.; Li, C.; Liang, Y.; Shroff, N. AI-EDGE: An NSF AI institute for future edge networks and distributed intelligence. AI Magazine 2024, 45(1), 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596(7873), 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junjun, R.; Zhengqian, Z.; Ying, W.; Jialiang, W.; Yongzhuang, L. A comprehensive review of deep learning-based variant calling methods. Briefings in Functional Genomics 2024, 23(4), 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheddar, H.; Himeur, Y.; Amira, A.; Soualah, R. Image and Point-cloud Classification for Jet Analysis in High-Energy Physics: A survey. Frontiers of Physics 2025, 20(3), 35301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, R.; Anastasiades, C.; Authur, R.; Beltagy, I.; Bragg, J.; Buraczynski, A.; Cachola, I.; Candra, S.; Chandrasekhar, Y.; Cohan, A.; Crawford, M.; Downey, D.; Dunkelberger, J.; Etzioni, O.; Evans, R.; Feldman, S.; Gorney, J.; Graham, D.; Hu, F.; Weld, D. S. The Semantic Scholar Open Data Platform. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2301.10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T. S.; Meyer, L. La structure des révolutions scientifiques; Flammarion Paris, 1983; Vol. 2, https://luci.univ-paris8.fr/IMG/pdf/19-03-2008.pdf.

- Liang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lepp, H.; Ji, W.; Zhao, X.; Cao, H.; Liu, S.; He, S.; Huang, Z.; Yang, D.; Potts, C.; Manning, C. D.; Zou, J. Y. Mapping the Increasing Use of LLMs in Scientific Papers. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.01268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Lu, C.; Lange, R. T.; Foerster, J.; Clune, J.; Ha, D. The AI Scientist: Towards Fully Automated Open-Ended Scientific Discovery. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.06292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, J.; Mullainathan, S. Machine learning as a tool for hypothesis generation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2024, 139(2), 751–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, H.; Mowla, N. I.; Abedin, S. F.; Thar, K.; Mahmood, A.; Gidlund, M.; Raza, S. Experimental analysis of trustworthy in-vehicle intrusion detection system using explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2022, 10, 102831–102841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhong, L.; Yan, C.; Srinivasan, M.; Seh, Z. W.; Liu, C.; Pan, H.; Li, S.; Wen, Y.; Yan, Q. Machine Learning: An Advanced Platform for Materials Development and State Prediction in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Advanced Materials 2022, 34(25), 2101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Shen, M.; Zhang, J. A Probe Towards Understanding GAN and VAE Models. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.05676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V. C.; Bostrom, N. Future Progress in Artificial Intelligence: A Survey of Expert Opinion. In Fundamental Issues of Artificial Intelligence; V. C., Müller, Ed.; Springer International Publishing, 2016; Vol. 376, pp. 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannini, L.; Balayn, A.; Smith, A. L. Explainability in AI Policies: A Critical Review of Communications, Reports, Regulations, and Standards in the EU, US, and UK. 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness Accountability and Transparency; 2023; pp. 1198–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019, 366(6464), 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R. B.; Teeple, S.; Navathe, A. S. Addressing bias in artificial intelligence in health care. Jama 2019, 322(24), 2377–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippidis, A. AI-Driven Pharma Tech Firm Expands Its Discovery Platform into Biologics: Exscientia intends to double the addressable target universe of its platform by combining generative AI design and virtual screening. Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News 2023, 43(1), 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popejoy, A. B.; Fullerton, S. M. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature 2016, 538(7624), 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, R.; Chang, P.-C.; Alexander, D.; Schwartz, S.; Colthurst, T.; Ku, A.; Newburger, D.; Dijamco, J.; Nguyen, N.; Afshar, P. T. A universal SNP and small-indel variant caller using deep neural networks. Nature Biotechnology 2018, 36(10), 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, R.; Varadarajan, A. V.; Blumer, K.; Liu, Y.; McConnell, M. V.; Corrado, G. S.; Peng, L.; Webster, D. R. Prediction of cardiovascular risk factors from retinal fundus photographs via deep learning. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2018, 2(3), 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prill, R. J.; Marbach, D.; Saez-Rodriguez, J.; Sorger, P. K.; Alexopoulos, L. G.; Xue, X.; Clarke, N. D.; Altan-Bonnet, G.; Stolovitzky, G. Towards a rigorous assessment of systems biology models: The DREAM3 challenges. PloS One 2010, 5(2), e9202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Pan, J.; Lyu, H.; Luo, J. Excitements and concerns in the post-chatgpt era: Deciphering public perception of ai through social media analysis. Telematics and Informatics 2024, 92, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccuglia, P.; Elbert, K. C.; Adler, P. D.; Falk, C.; Wenny, M. B.; Mollo, A.; Zeller, M.; Friedler, S. A.; Schrier, J.; Norquist, A. J. Machine-learning-assisted materials discovery using failed experiments. Nature 2016, 533(7601), 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z.; Hussain, A.; Rahaman, M. S.; Ansari, K. M. Mapping artificial intelligence in medical diagnosis in india: A bibliometric analysis. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries 2024, 13(4), 607–639. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Li, J. CRESt–copilot for real-world experimental scientist. 2023. https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/655417d1dbd7c8b54b477786.

- Rifkin, R. M. Everything old is new again: A fresh look at historical approaches in machine learning. PhD Thesis, MaSSachuSettS InStitute of Technology, 2002. https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/17549.

- Sejnowski, T. J. The deep learning revolution; MIT press, 2018; https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9xZxDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=deep+learning+revolution+of+the+2010s+&ots=SIPaQ8sxSc&sig=opSLSB_3RO9JnhqVVeOyauX0UXI.

- Thomas, S. J.; Barr, J.; Callahan, S.; Clements, A. W.; Daruich, F.; Fabrega, J.; Ingraham, P.; Gressler, W.; Munoz, F.; Neill, D. Vera C. Rubin Observatory: Telescope and site status. Ground-Based and Airborne Telescopes VIII 2020, 11445, 68–82. https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/11445/114450I/Vera-C-Rubin-Observatory-telescope-and-site-status/10.1117/12.2561581.short.

- Topol, E. J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine 2019, 25(1), 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadegan, H.; Martinho, M. J.; Wilkens, L. S.; Jenkins, J. M.; Smith, J. C.; Caldwell, D. A.; Twicken, J. D.; Gerum, P. C.; Walia, N.; Hausknecht, K. ExoMiner: A highly accurate and explainable deep learning classifier that validates 301 new exoplanets. The Astrophysical Journal 2022, 926(2), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Uszkoreit, H.; Du, Y.; Fan, W.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, J. Explainable AI: A Brief Survey on History, Research Areas, Approaches and Challenges. In Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing; Tang, J., Kan, M.-Y., Zhao, D., Li, S., Zan, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2019; Vol. 11839, pp. 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Lange, R. T.; Lu, C.; Hu, S.; Lu, C.; Foerster, J.; Clune, J.; Ha, D. The AI Scientist-v2: Workshop-Level Automated Scientific Discovery via Agentic Tree Search. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.08066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, T.; Li, H.; Chang, P.-C.; Lin, M. F.; Carroll, A.; McLean, C. Y. Accurate, scalable cohort variant calls using DeepVariant and GLnexus. Bioinformatics 2020, 36(24), 5582–5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Dafoe, A. Artificial intelligence: American attitudes and trends. Available at SSRN 3312874. 2019. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3312874.

- Zhao, S.; Blaabjerg, F.; Wang, H. An overview of artificial intelligence applications for power electronics. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2020, 36(4), 4633–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhavoronkov, A.; Ivanenkov, Y. A.; Aliper, A.; Veselov, M. S.; Aladinskiy, V. A.; Aladinskaya, A. V.; Terentiev, V. A.; Polykovskiy, D. A.; Kuznetsov, M. D.; Asadulaev, A. Deep learning enables rapid identification of potent DDR1 kinase inhibitors. Nature Biotechnology 2019, 37(9), 1038–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case Studies | Provide rich, contextual insights into AI applications, capturing complex interactions between technology and science. | Often context-specific, limiting generalizability; prone to selection bias, overrepresenting successful cases. | AlphaFold’s protein folding solution |

| Experimental Studies | Offer rigorous evidence of causality and quantitative comparisons, ideal for assessing AI’s effectiveness. | Controlled settings may not reflect real-world complexities; scaling results to practical applications can be challenging. | AI-optimized chemical synthesis |

| Surveys and Interviews | Excel at capturing subjective experiences and human perspectives, essential for understanding AI adoption barriers. | Susceptible to biases like social desirability or sampling issues; qualitative data interpretation can be subjective. | Scientists’ concerns about AI ethics |

| Data Mining and Bibliometric Analyses | Handle large datasets efficiently, providing objective, macro-level insights into trends and patterns. | Depend on data quality; risk of misinterpretation if analytical methods are not robust. | AI publication trends in drug discovery |

| Simulations | Offer flexibility and cost-effectiveness for testing AI in impractical scenarios. | Validity hinges on accurate underlying models; unrealistic assumptions can undermine results. | Material discovery simulations |

| Theoretical Modeling | Provide structured frameworks for understanding AI’s role, guiding empirical research. | Risk being speculative without empirical validation, disconnecting from practical applications. | AI’s impact on hypothesis generation |

| Field | AI Application | Example | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Astronomy | Galaxy classification, exoplanet detection | Neural networks on Sloan Digital Sky Survey, Kepler data | High accuracy (98% for galaxies, 96% for exoplanets), manages large datasets |

| Genomics | Variant calling, splicing prediction | DeepVariant, SpliceAI | Improved accuracy, identifies disease-related variants |

| Particle Physics | Event reconstruction, particle identification | CMS and ATLAS experiments | Enhanced sensitivity to new physics, precise measurements |

| Field | Theme A (Data Analysis) | Theme B (Hypothesis Generation) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DeepVariant identifies genetic variants | Hypotheses about disease associations | Targeted experiments validate gene-disease links |

| Astronomy | Galaxy classification with 98% accuracy |

Hypotheses on galaxy formation |

Observations refine cosmic models |

| Materials Science | A-Lab screens 32M materials | Hypotheses on new battery compounds |

Synthesis of working prototype |

| Particle Physics | LHC data anomaly detection | Hypotheses on new particles | Further collisions test new physics theories |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).