Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. INTRODUCTION

II. Problem Formulation and Preliminaries

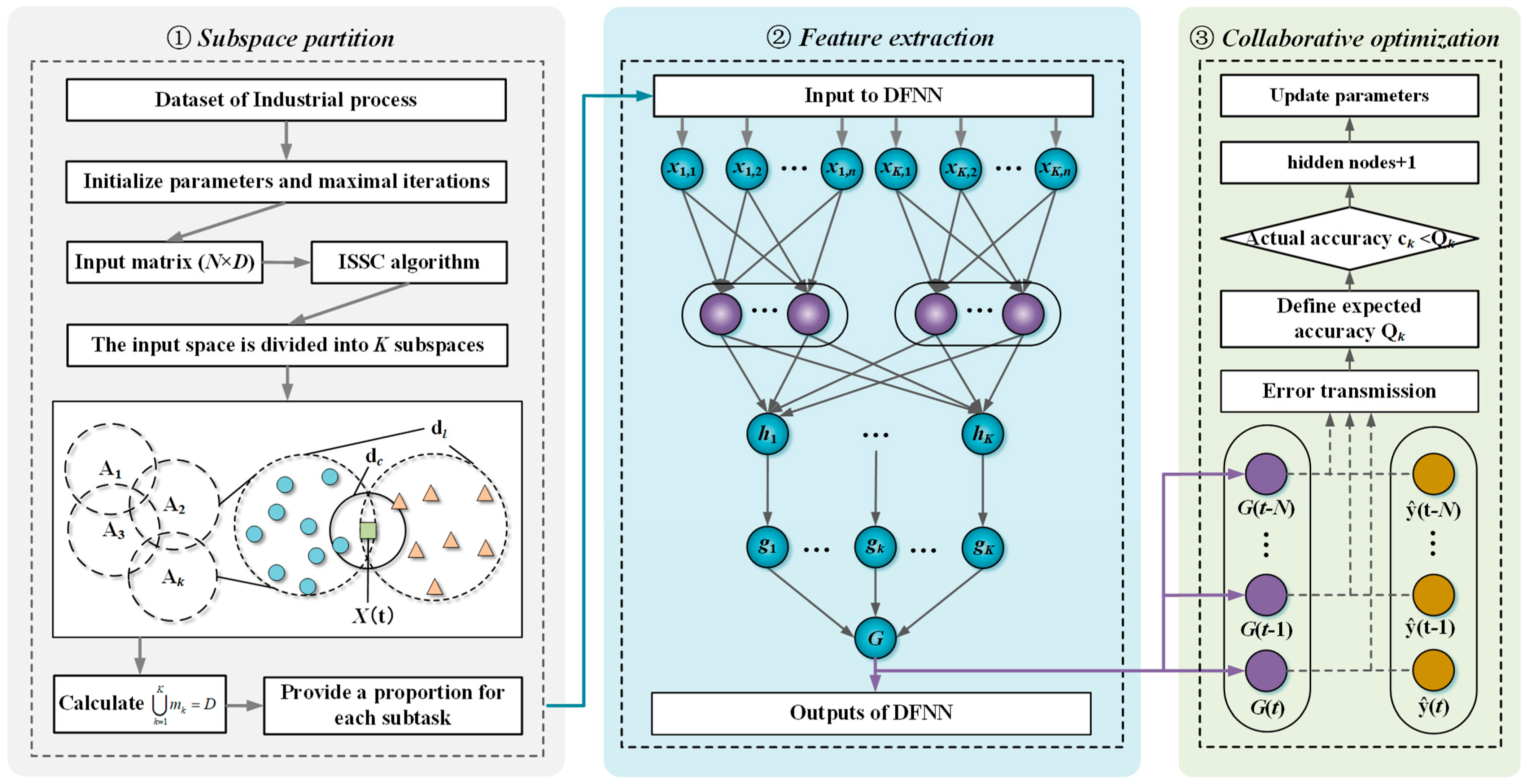

III. Architecture of ISSC-DFNN

IV. Algorithm design of ISSC-DNN

- A.

- The subspace partition method of spectral clustering

- B.

- Construction of subnetwork

- 1)

- Structure of subnetworks

- 2)

- Structure of subnetworks

- 3)

- Self-constructing of subnetworks

- C.

- Collaborative optimization algorithm

| 1: T=1, Set the maximum number of iterations to T0; 2: Initialize expected accuracy Qk, global variables β∗, and neural network parameters, and wQk; 3: Repeat: 4: Repeat: T=T+1; 5: Calculate the output of each neural subnet according to Eq (14); 6: Calculate the output error δk of each subnet according to Eq (17); 7: The global variable βi of each subnet can be obtained according to Eq (16); 8: Update subnet parameters by according to (18); 9: Until T> T0 10: The accuracy cQk of the network is calculated according to Eq (15). 11: hidden nodes = hidden nodes + 1; 7: Until cQk < Qk; |

V. Simulation Studies

- A.

- Experimental datasets

- 1)

- Benchmark problems

- 2)

- ETP in wastewater treatment

- B.

- Experimental setup

- C.

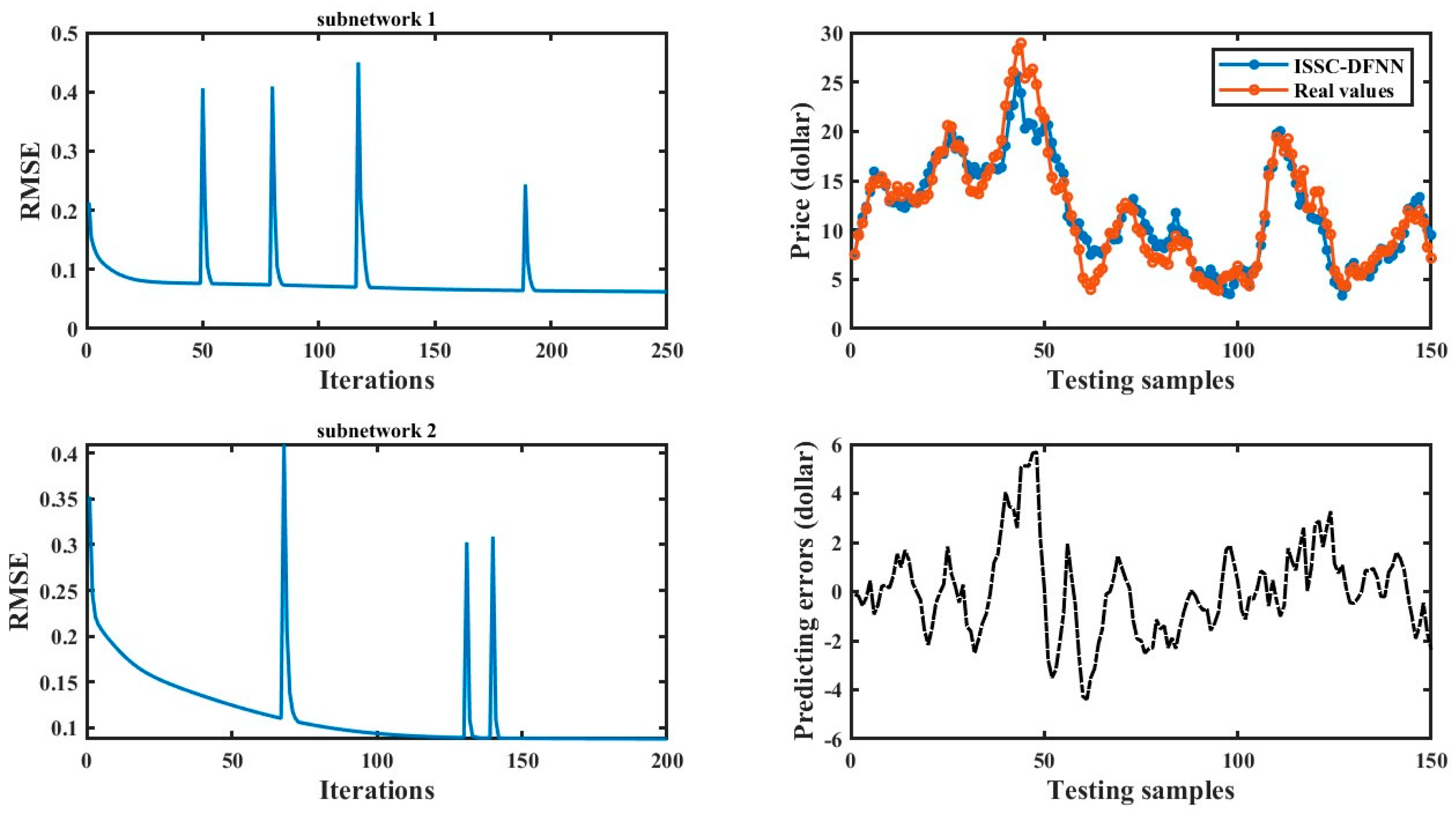

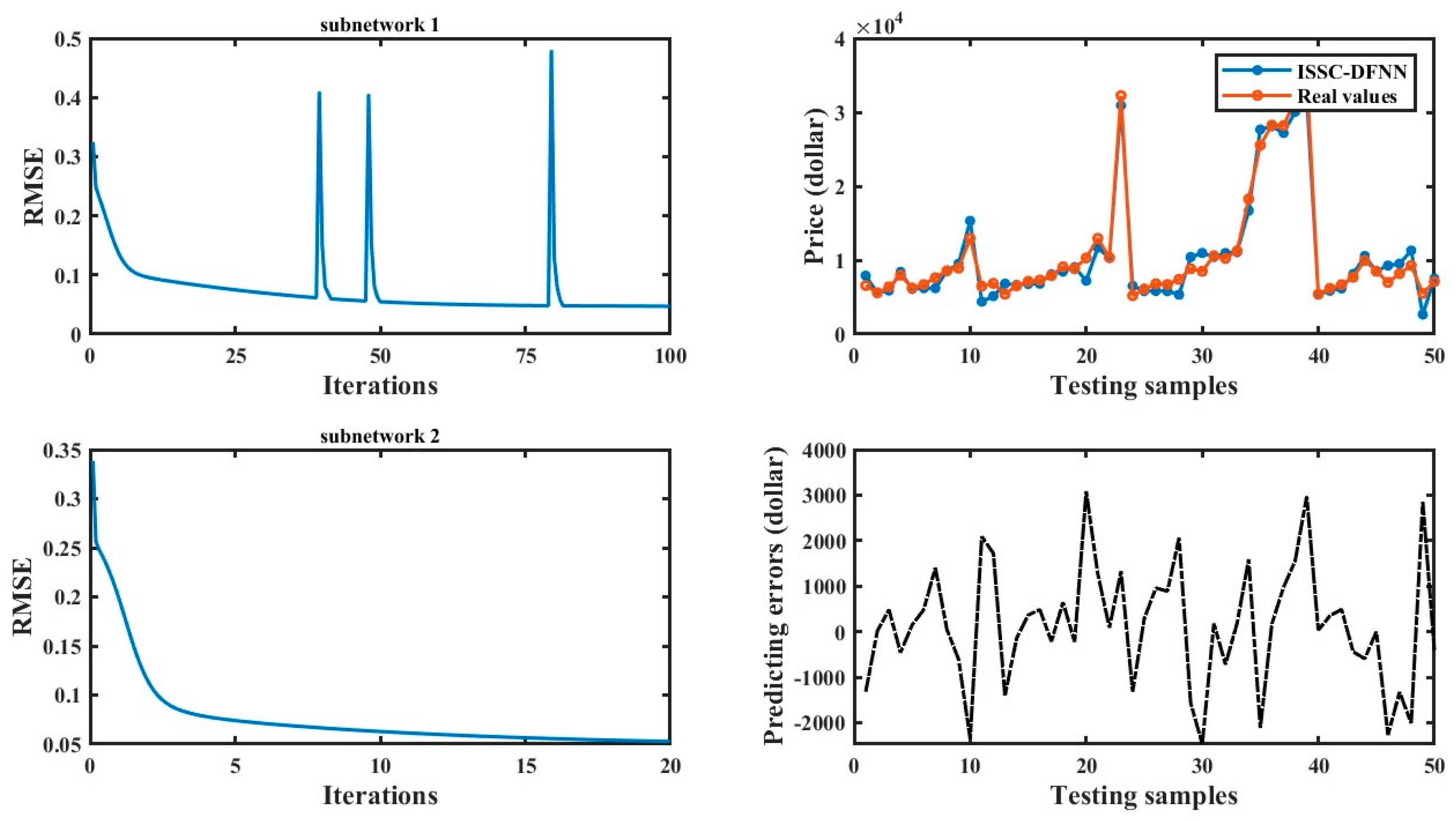

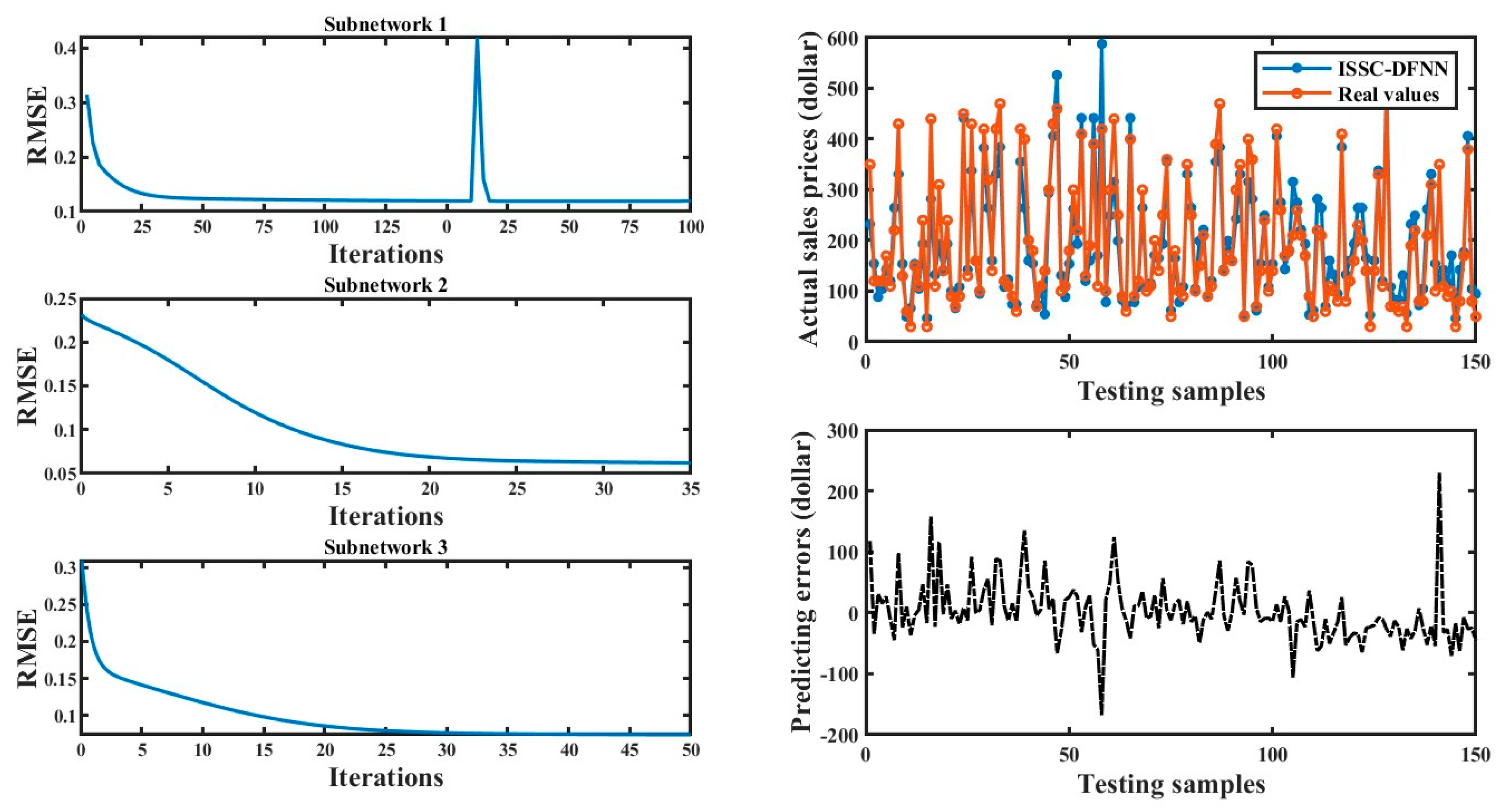

- Prediction results on benchmark problems

- D.

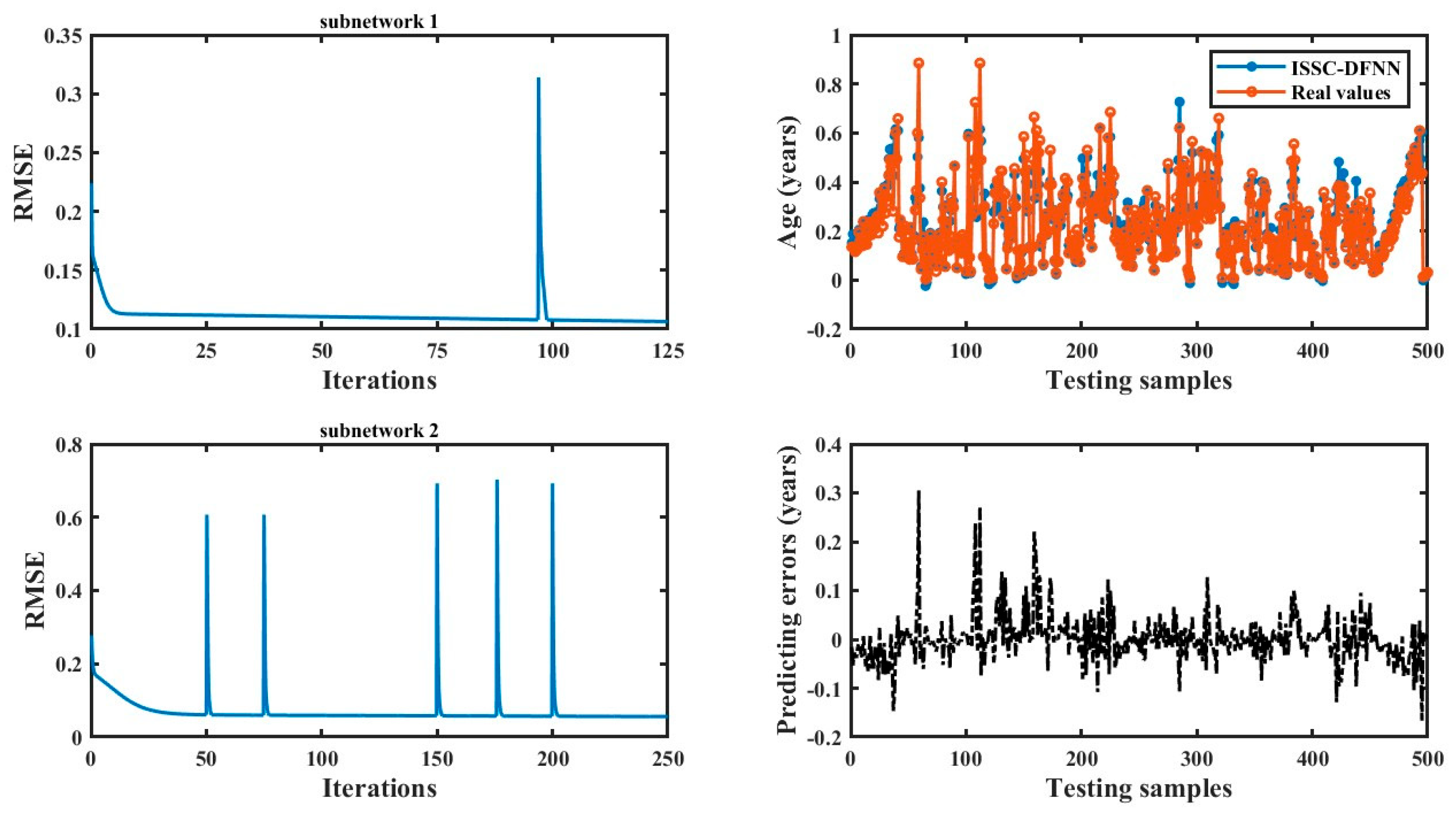

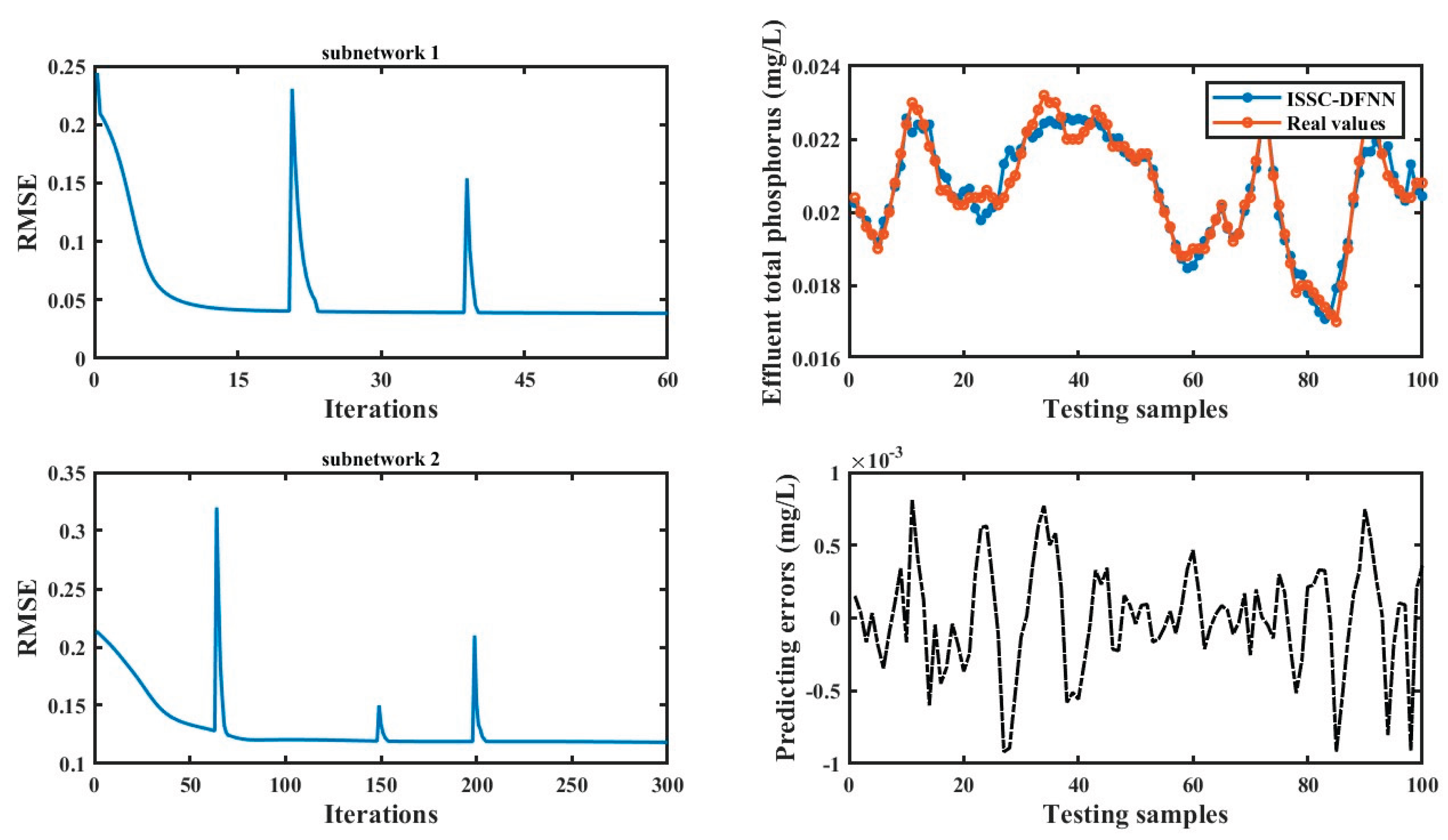

- Results on ETP in wastewater treatment prediction

- E.

- Statistical analysis

VI. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Lin, F.J.; Sun, I.F.; Yang, K.J.; Chang, J.K. Recurrent fuzzy neural cerebellar model articulation network fault-tolerant control of six-phase permanent magnet synchronous motor position servo drive. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2016, 24, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.T.; Lin, Y.Y.; Wu, S.L.; Chuang, C.H.; Lin, C.T. Brain dynamics in predicting driving fatigue using a recurrent self-evolving fuzzy neural network. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning System 2016, 27, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.J.; Ling, H.F.; Chen, S.Y.; Xue, J.Y. A hybrid neuro-fuzzy network based on differential biogeography-based optimization for online population classification in earthquakes. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2015, 23, 1070–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.F.; Lim, C.P. An enhanced fuzzy Min–Max neural network for pattern classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2015, 26, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, R.J.; Chen, M.W.; Liu, Y.K. Design of adaptive control and fuzzy neural network control for single-stage boost inverter. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2015, 62, 5434–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjefar, S.; Tofighi, M. Single-hidden-layer fuzzy recurrent wavelet neural network: Applications to function approximation and system identification. Information Sciences 2015, 294, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofighi, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Ganjefar, S.; Alizadeh, M. Direct adaptive power system stabilizer design using fuzzy wavelet neural network with self-recurrent consequent part. Applied Soft Computing 2015, 28, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakkiyappan, R.; Balasubramaniam, P. On exponential stability results for fuzzy impulsive neural networks. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 2010, 161, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wu, C. Approximation of fuzzy functions by regular fuzzy neural networks. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 2011, 177, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, R.J.; Chen, M.W.; Liu, Y.K. Design of adaptive control and fuzzy neural network control for single-stage boost inverter. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2015, 62, 5434–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D.; Prasad, G.; McGinnity, T.M. Faster self-organizing fuzzy neural network training and a hyperparameter analysis for a brain–computer interface. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B: Cybernetics 2009, 39, 1458–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanualailai, J.; Nakagiri, S. Some generalized sufficient convergence criteria for nonlinear continuous neural networks. Neural computation 2005, 17, 1820–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Li, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y. A modified gradient-based neuro-fuzzy learning algorithm and its convergence. Information Sciences 2010, 180, 1630–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davanipoor, M.; Zekri, M.; Sheikholeslam, F. Fuzzy wavelet neural network with an accelerated hybrid learning algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2012, 20, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Li, C.T.; Chang, F.Y. A species-based improved electromagnetism-like mechanism algorithm for TSK-type interval-valued neural fuzzy system optimization. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 2011, 171, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Jiang, L. Some research on Levenberg–Marquardt method for the nonlinear equations. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2007, 184, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, M.; Orlowska-Kowalska, T. An online trained neural controller with a fuzzy learning rate of the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm for speed control of an electrical drive with an elastic joint. Applied Soft Computing 2015, 32, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.K.; Sun, T.Y.; Huo, C.L.; Yu, Y.H.; Liu, C.C.; Tsai, C.H. A novel self-constructing radial basis function neural-fuzzy system. Applied Soft Computing 2013, 13, 2390–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampazis, N.; Perantonis, S.J. Two highly efficient second-order algorithms for training feedforward networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 2002, 13, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, K.; Irwin, G.W. A new gradient descent approach for local learning of fuzzy neural models. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2013, 21, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.P.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.H.; Chen, L. A new learning algorithm for a fully connected neuro-fuzzy inference system. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2014, 25, 1741–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzeng, S.T. Design of fuzzy wavelet neural networks using the GA approach for function approximation and system identification. Fuzzy sets and systems 2010, 161, 2585–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, R.J.; Hung, S.Y.; Cheng, W.C. Application of an optimization artificial immune network and particle swarm optimization-based fuzzy neural network to an RFID-based positioning system. Information Sciences 2014, 262, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashinchi, M.R.; Selamat, A. An improvement on genetic-based learning method for fuzzy artificial neural networks. Applied Soft Computing 2009, 9, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Lin, C.J.; Lin, C.T. Nonlinear system control using adaptive neural fuzzy networks based on a modified differential evolution. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C: Applications and Reviews 2009, 39, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.G.; Wu, X.L.; Qiao, J.F. Nonlinear systems modeling based on self-organizing fuzzy-neural-network with adaptive computation algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2014, 44, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranian, A.; Abdollahzade, M. Developing a local least-squares support vector machines-based neuro-fuzzy model for nonlinear and chaotic time series prediction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2013, 24, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Reiner, P.D.; Xie, T.; Bartczak, T.; Wilamowski, B.M. An incremental design of radial basis function networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2014, 25, 1793–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Er, M.J.; Gao, Y. A fast approach for automatic generation of fuzzy rules by generalized dynamic fuzzy neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2001, 9, 578–594. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Er, M.J. Dynamic fuzzy neural networks-a novel approach to function approximation. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B: Cybernetics 2000, 30, 358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Teslic, L.; Hartmann, B.; Nelles, O.; Skrjanc, I. Nonlinear system identification by Gustafson–Kessel fuzzy clustering and supervised local model network learning for the drug absorption spectra process. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 2011, 22, 1941–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Er, M.J.; Meng, X. A fast and accurate online self-organizing scheme for parsimonious fuzzy neural networks. Neurocomputing 2009, 72, 3818–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J.J. SOFMLS: online self-organizing fuzzy modified least-squares network. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2009, 17, 1296–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.G.; Qiao, J.F. A self-organizing fuzzy neural network based on a growing-and-pruning algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2010, 18, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, K.; He, H.; Irwin, G.W. A new discrete-continuous algorithm for radial basis function networks construction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2013, 24, 1785–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, Y.C. Nonlinear systems design by a novel fuzzy neural system via hybridization of electromagnetism-like mechanism and particle swarm optimisation algorithms. Information Sciences 2012, 186, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.K.; Kim, W.D.; Pedrycz, W.; Seo, K. “Fuzzy radial basis function neural networks with information granulation and its parallel genetic optimization. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 2014, 237, 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, C.F.; Cheng, W.; Liang, C. Speedup of learning in interval type-2 neural fuzzy systems through graphic processing units. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2015, 23, 1286–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, K. An efficient LS-SVM-based method for fuzzy system construction. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2015, 23, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, C.F.; Lin, Y.Y.; Tu, C.C. A recurrent self-evolving fuzzy neural network with local feedbacks and its application to dynamic system processing. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 2010, 161, 2552–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Er, M.J.; Han, M. Dynamic tanker steering control using generalized ellipsoidal- basis-function-based fuzzy neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2015, 23, 1414–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonidandel, S.; Lebreton, J.M. Relative importance analysis: a useful supplement to regression analysis. Journal of Business & Psychology 2011, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, Y.C.E.; Zhao, Y.; Kupper, L.L.; Nylander-French, L.A. “Quantifying the relative importance of predictors in multiple linear regression analyses for public health studies. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Hygiene 2008, 5, 519–529. [Google Scholar]

- Gacek, A.; Pedrycz, W. Clustering granular data and their characterization with information granules of higher type. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2015, 23, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. M.; Sim; Guo, Y.; Shi, B. BLGAN: Bayesian learning and genetic algorithm for supporting negotiation with incomplete information. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Part B: Cybernetics 2009, 39, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Gong, Y.; Hong, X. Online modeling with tunable RBF network. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2013, 43, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubrowska-Sudol, M.; Walczak, J. Enhancing combined biological nitrogen and phosphorus removal from wastewater by applying mechanically disintegrated excess sludge. Water Research 2015, 76, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, C.; Glen, C.; Aubie, B.; Wallace, D.; Jahanshahi-Anbuhi, S.; Pennings, K.; Daigger, G.T.; Pelton, R.; Brennan, J.D.; Filipe, C.D.M. Tools for water quality monitoring and mapping using paper-based sensors and cell phones. Water Research 2015, 70, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.K.; Ettwig, K.F.; Vannecke, T.P.; Stultiens, K.; Bogdan, A.; Kartal, B.; Volcke, E.I.P. Modelling simultaneous anaerobic methane and ammonium removal in a granular sludge reactor. Water Research 2015, 73, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujer, W. Nitrification and me-A subjective review. Water Research 2010, 44, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin, D.; Manser, R.; Rieger, L.; Eugster, J.; Rottermann, K.; Siegrist, H. Extension of ASM3 for two-step nitrification and denitrification and its calibration and validation with batch tests and pilot scale data. Water Research 2009, 43, 1680–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1: C=1 2: Initialize the parameters and set the maximum number of iterations to Max. 3: Repeat: 4: C=C+1; 5: Arbitrarily initialize cluster centers matrix V(0), initialize the weight matrix W(0). 6: Repeat: iter = iter + 1; 7: Calculate the membership matrix U(iter) according to Eq. (4); 8: Calculate the weight matrix W(iter) according to Eq. (6); 9: Until ||V(iter)-V(iter-1)||<ζ or iter = Max. 10: Calculate the JIESSC by Eq. (2); 11: Until C = 2log(D); D is the number of input features. 12: Calculate the minimum value of J and the optimal clusters K. |

| Dataset | Training samples | Testing samples | Input dimensions | Output dimension |

| Boston Housing | 350 | 150 | 13 | 1 |

| Auto Price | 120 | 50 | 14 | 1 |

| Abalone | 1500 | 500 | 8 | 1 |

| Residential building | 350 | 150 | 107 | 1 |

| X1 | Inlet flow | X13 | BOD |

| X2 | Temperature | X14 | Influent oil |

| X3 | ORP1 | X15 | Effluent oil |

| X4 | ORP2 | X16 | Influent ammonia |

| X5 | MLSS1 | X17 | Influent colourity |

| X6 | NO3-N | X18 | Effluent colourity |

| X7 | NH4-N | X19 | Influent PH |

| X8 | DO1 | X20 | Effluent PH |

| X9 | ORP3 | X21 | Suspended Solid |

| X10 | MLSS2 | X22 | Influent nitrogen |

| X11 | NO3-N | X23 | Influent phosphate |

| X12 | DO2 | Yd | ETP |

| Algorithm | Dataset A: Boston Housing | Dataset B: Auto Price | ||||||

| Training RMSE |

Testing RMSE |

Testing APE |

Subnetworks | Training RMSE |

Testing RMSE |

Testing APE |

Subnetworks | |

| Prop. | 0.0759 | 0.0741 | 0.1375 | 2 | 0.0738 | 0.0742 | 0.1729 | 2 |

| FC-AMNN | 0.0767 | 0.0748 | 0.1396 | 4 | 0.0752 | 0.0766 | 0.1781 | 2 |

| TMNN | 0.0875 | 0.0906 | 0.1684 | 2 | 0.0872 | 0.0883 | 0.1968 | 2 |

| OSAMNN | 0.0927 | 0.1006 | 0.1734 | 8 | 0.0785 | 0.0810 | 0.1892 | 5 |

| Algorithm | Dataset C: Abalone | Dataset D: Residential building | ||||||

| Training RMSE |

Testing RMSE |

Testing APE |

Subnetworks | Training RMSE |

Testing RMSE |

Testing APE |

Subnetworks | |

| Prop. | 0.0739 | 0.0741 | 0.1721 | 2 | 0.0987 | 0.0962 | 0.467 | 3 |

| FC-AMNN | 0.0774 | 0.0786 | 0.1797 | 2 | 0.0994 | 0.1062 | 0.4963 | 4 |

| TMNN | 0.0823 | 0.0886 | 0.1895 | 2 | 0.1152 | 0.1204 | 0.5397 | 3 |

| OSAMNN | 0.0815 | 0.0879 | 0.1838 | 7 | 0.1074 | 0.1126 | 0.5124 | 4 |

| Algorithm | Training RMSE |

Testing RMSE |

Testing APE |

Subnetwork |

| Prop. | 0.0763 | 0.0781 | 0.0306 | 2 |

| FC-AMNN | 0.0802 | 0.0816 | 0.0391 | 2 |

| TMNN | 0.0984 | 0.0996 | 0.0502 | 3 |

| OSAMNN | 0.0795 | 0.0828 | 0.0412 | 7 |

| Models | R+ | R- | Pwilconxon |

| Prof. vs TMNN | 21 | 0 | 0.00741 |

| Prof. vs FC-AMNN | 21 | 0 | 0.00741 |

| Prof. vs OSAMNN | 21 | 0 | 0.00741 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).