1. Introduction

The modern healthcare system produces a massive volume of data every day, with hospitals estimated to generate over 50 petabytes of information annually [

1]. A significant proportion of this data up to 80%is unstructured, comprising clinical notes, patient-provider communication threads, administrative records, and other narrative content [

2]. This unstructured data poses substantial challenges for traditional data processing methods due to its irregular format, medical jargon, and contextual ambiguity. Efficient management and classification of healthcare data can play a crucial role in improving operational workflows, enabling more responsive patient care, and reducing administrative burden. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into healthcare, particularly through machine learning and LLMs, has shown significant potential in automating various tasks and enhancing communication pathways within clinical settings [

3]. For instance, identifying urgent messages from patients or distinguishing between appointment requests and medical questions promptly can directly impact healthcare outcomes and staff workload [

4]. Studies have indicated that implementing machine learning approaches can optimize workflows and provide substantial benefits regarding patient care management [

5,

6,

7]. Our work focuses on this important direction as we seek to develop strategies that enhance the efficiency and responsiveness of healthcare services.

For text classification in healthcare applications, traditional approaches, such as rule-based systems and classical machine learning methods, have been used widely but often lack scalability and adaptability. Prior studies have explored the use of support vector machines (SVMs), decision trees, and ensemble learning techniques for clinical text classification [

8,

9]. However, these approaches require extensive feature engineering and struggle with contextual variations.

Deep learning-based methods, particularly those leveraging recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated improved performance in classifying electronic health records (EHRs) [

10]. More recently, transformer-based models, such as BERT and its domain-specific adaptations like BioBERT and ClinicalBERT, have achieved state-of-the-art results in medical NLP tasks [

11,

12]. These models leverage contextual embeddings, significantly improving accuracy over static word embeddings.

Despite the effectiveness of domain-specific Large Language Models (LLMs), recent advances in general-purpose models like GPT-4 have shown remarkable adaptability across various NLP tasks, including medical text classification [

13]. Studies comparing specialized and general LLMs indicate that fine-tuning large generalist models on domain-specific data can outperform specialized models in classification tasks [

14]. Our study builds upon this research by comparing a number of LLMs inlcuding BioBERT [

11], ClinicalBERT [

12], and GPT-based [

15] models for hospital message classification.

Recent developments in natural language processing (NLP), particularly through the rise of large language models (LLMs), have enabled more accurate and scalable solutions for handling such complex, text-heavy tasks. These models have proven effective across domains, including answering clinical examination questions [

16], generating radiology and discharge summaries [

17], and supporting administrative workflows [

18].

However, healthcare applications of LLMs must contend with unique challenges. These include domain-specific vocabulary, strict privacy constraints, variations in communication styles between patients and clinicians, and the high cost of misclassifications in sensitive contexts. Models must not only understand medical concepts but also generalize across diverse patient populations and communication settings.

This paper focuses on the real-world implementation of large language models (LLMs) for classifying patient messages exchanged through the Electronic Medical Records (EMR) platform. Our limited dataset was collected from a hospital system based in central Illinois and was carefully de-identified to ensure compliance with HIPAA regulations [

19]. We evaluated the performance of domain-specific models, BioBERT and ClinicalBERT and compared them to GPT-4o, a powerful general-purpose model from OpenAI. We explore both few-shot prompting and fine-tuning strategies to determine which approach best suits the complexity and variability of clinical message classification. Our major contributions are summarized as below.

We introduce a practical framework for classifying outpatient messages using both domain-specific and general-purpose LLMs.

We conduct a comparative evaluation of BioBERT, ClinicalBERT, and GPT-4o across urgency detection and multi-label categorization tasks.

We present insights on the fine-tuning process within a secure hospital cloud environment, highlighting accuracy gains, ethical safeguards, and deployment considerations.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 lays the foundation of this work. The description of used LLM models and data set are stated in

Section 3. Comprehensive results and analysis are stated in

Section 4, followed by a discussion summary in

Section 5. We finally conclude this paper in

Section 6.

2. Motivation

In today’s fast-paced healthcare environment, timely communication between patients and providers is crucial. Every day, HealthCare systems receive a high volume of patient messages ranging from appointment requests to urgent medical concerns. However, managing this influx of messages efficiently poses a significant challenge. The current system relies on significant human involvement for message management. While this approach ensures careful attention, it can also make it challenging to consistently prioritize messages, sometimes resulting in added pressure on providers.

To address this challenge, we propose an innovative, AI-driven solution that leverages a customized OpenAI model (fine-tuned ChatGPT-4o) to automate message classification and response generation. Our goal is to develop an intelligent system that not only categorizes messages based on urgency and content but also suggests appropriate responses or routes them to the right healthcare professionals. By integrating this system with the Hospital Community Connect (HCC) platform, we aim to create a seamless and efficient communication workflow that enhances patient engagement and provider efficiency.

The motivation behind this project is twofold. First, it seeks to alleviate the burden on healthcare workers, allowing them to focus on direct patient care rather than administrative tasks. Second, it aims to ensure that urgent patient concerns are addressed promptly, improving health outcomes and patient satisfaction. Given the limitations of off-the-shelf AI models in handling nuanced, multi-class classification tasks in healthcare, we plan to build a domain-specific, fine-tuned model trained on real-world patient messages. This approach will enable our system to achieve higher accuracy and reliability in classifying and responding to messages. Our motivation is both practical and visionary:

Operational Impact: By automating classification, we can reduce administrative workload and improve response times.

Clinical Relevance: Accurate triage ensures that critical health issues are identified and escalated without delay.

Technological Advancement: We test the hypothesis that a fine-tuned general-purpose LLM can outperform existing domain-specific models in nuanced, multi-label classification tasks.

By leveraging cutting-edge natural language processing techniques and AI-driven automation, this project has the potential to revolutionize patient-provider communication. It represents a step towards a more responsive, efficient, and patient-centered healthcare system where technology empowers providers and patients to engage more effectively. We believe our work will advance the application of AI in healthcare and set a precedent for future AI-driven innovations in clinical communication and digital health solutions.

3. Methodology

Several large language models were evaluated, including BioBERT, ClinicalBERT, and GPT-4o. Each model was tested without fine-tuning. The goal was to determine which model performed best in classifying healthcare system messages across three tasks: urgency classification, category identification, and multi-label classification.

The rationale for employing multiple types of message classification stems from the nature of real-world clinical communication. Patient messages often contain multiple intents and vary in urgency. An effective triage system must be able to identify both the immediacy of response required and the specific type(s) of inquiry, whether administrative, clinical, or logistical.

Urgency classification is vital for ensuring timely responses to critical issues that could impact patient safety or outcomes. Simultaneously, category identification enables accurate routing of messages to the appropriate healthcare personnel or department. For example, a message requesting an urgent medication refill differs significantly in handling from one rescheduling a routine follow-up appointment.

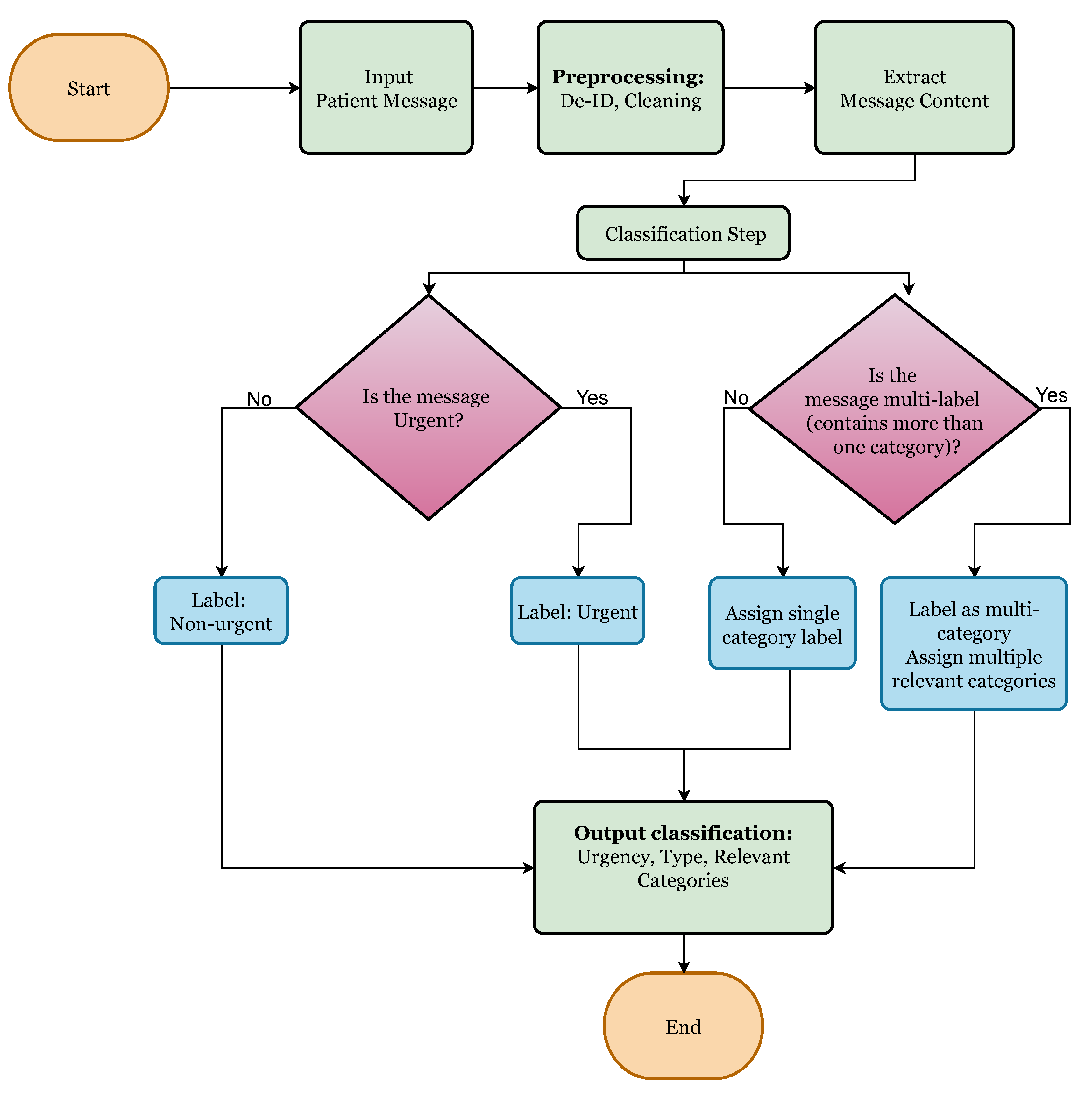

To illustrate this,

Table 1 presents de-identified examples of patient messages along with their urgency level, message type, and associated categories.

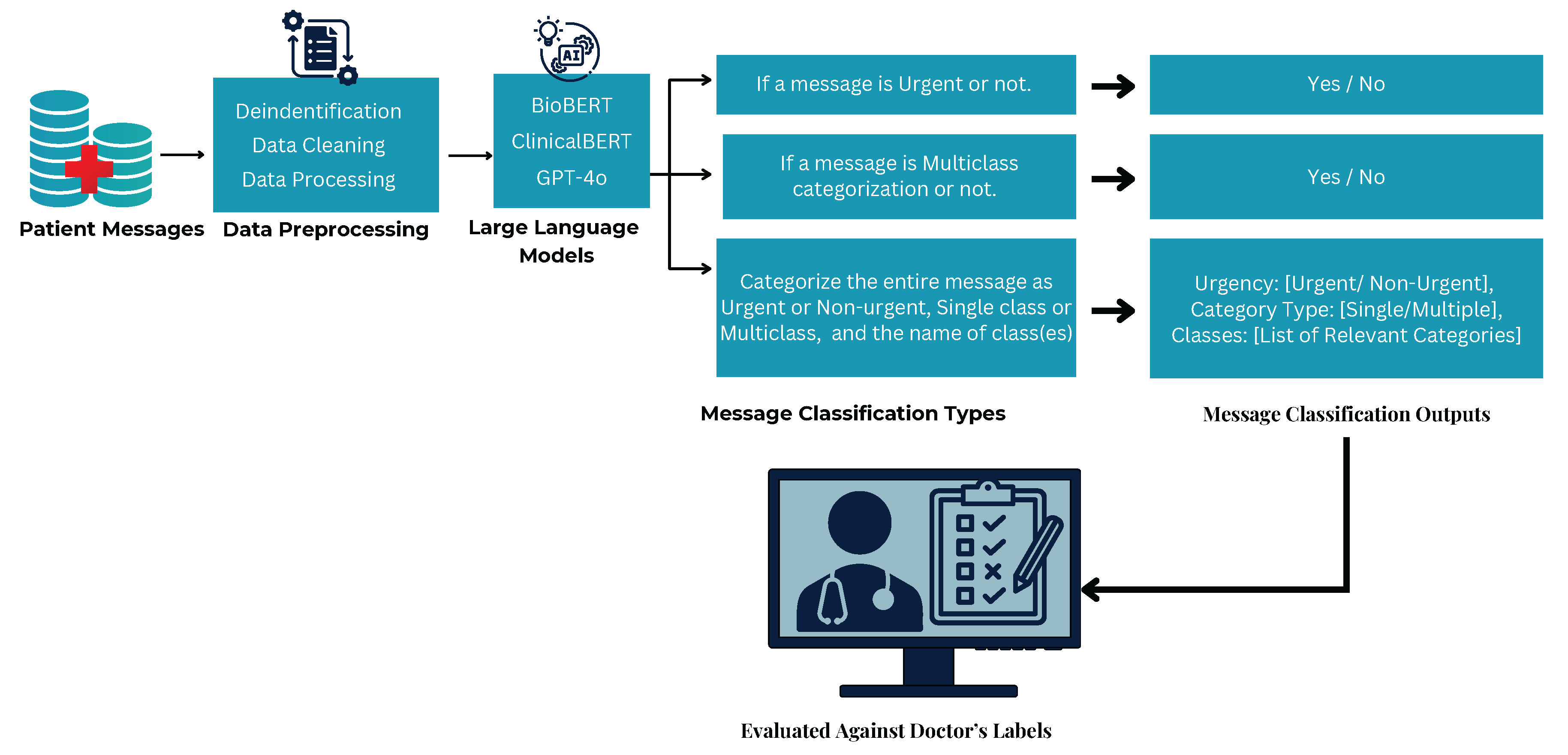

To operationalize this classification pipeline, we designed a decision-based flowchart,

Figure 1 to guide how a message is processed. The process begins with evaluating whether the message is urgent or not urgent after categorizing the urgency, the next step assesses whether the message involves a single issue or multiple distinct concerns. Finally, based on content, the model assigns one or more labels from the pre-defined category set.

3.1. Dataset Description

This study utilizes a real-world hospital dataset containing patient messages collected from an internal hospital communication system. The dataset includes textual messages related to administrative inquiries, appointment scheduling, medication refills, and clinical updates. Data preprocessing involved de-identification, so all personally identifiable information (PII) was removed to comply with HIPAA regulations.

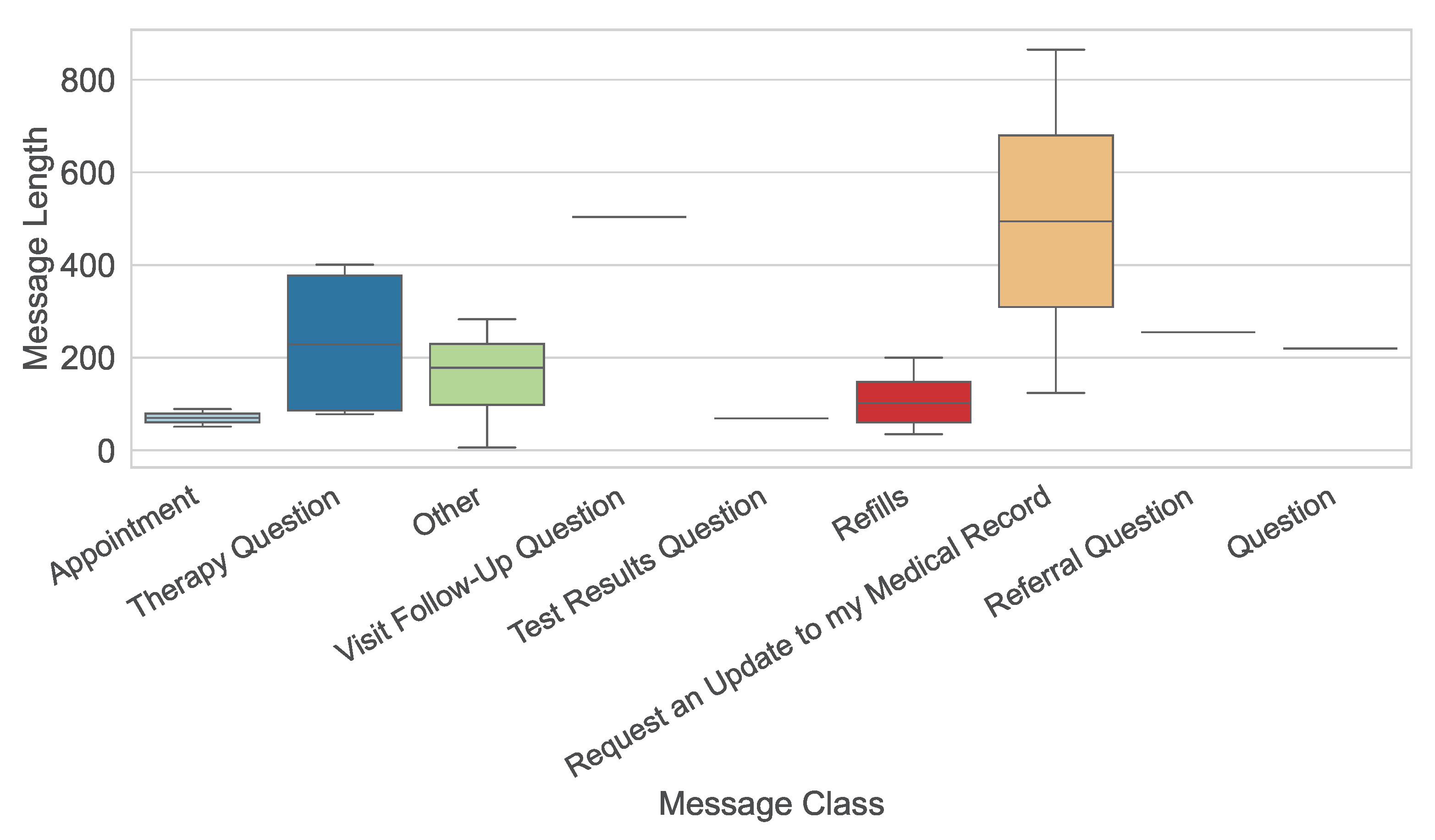

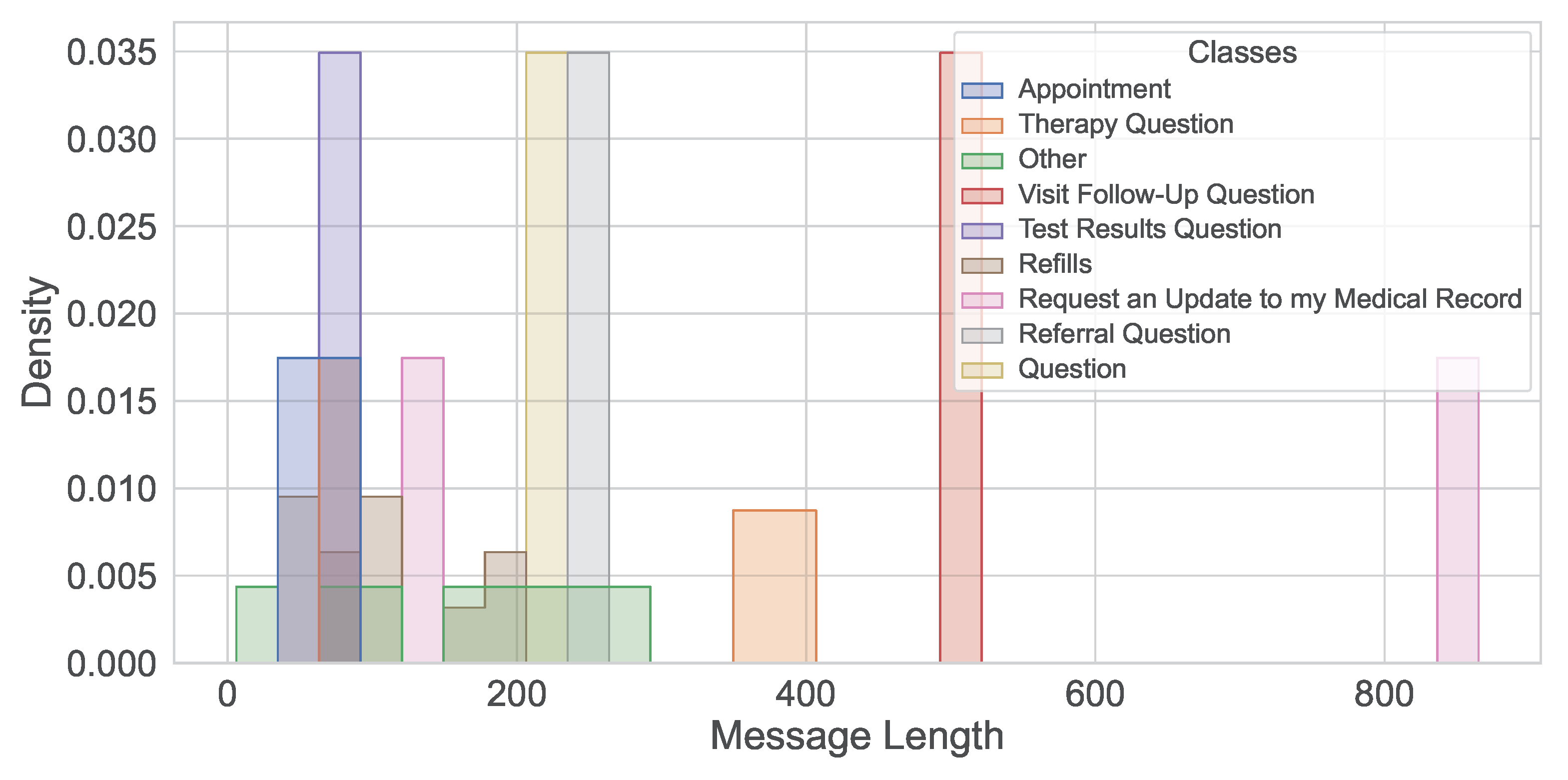

120 of them labeled by a hospital doctor who has been very familiar with the outpatients messages communication system over the years. This labeled data set has been used for training and testing the LLMs studied. The distribution of messages by their true classes is shown in

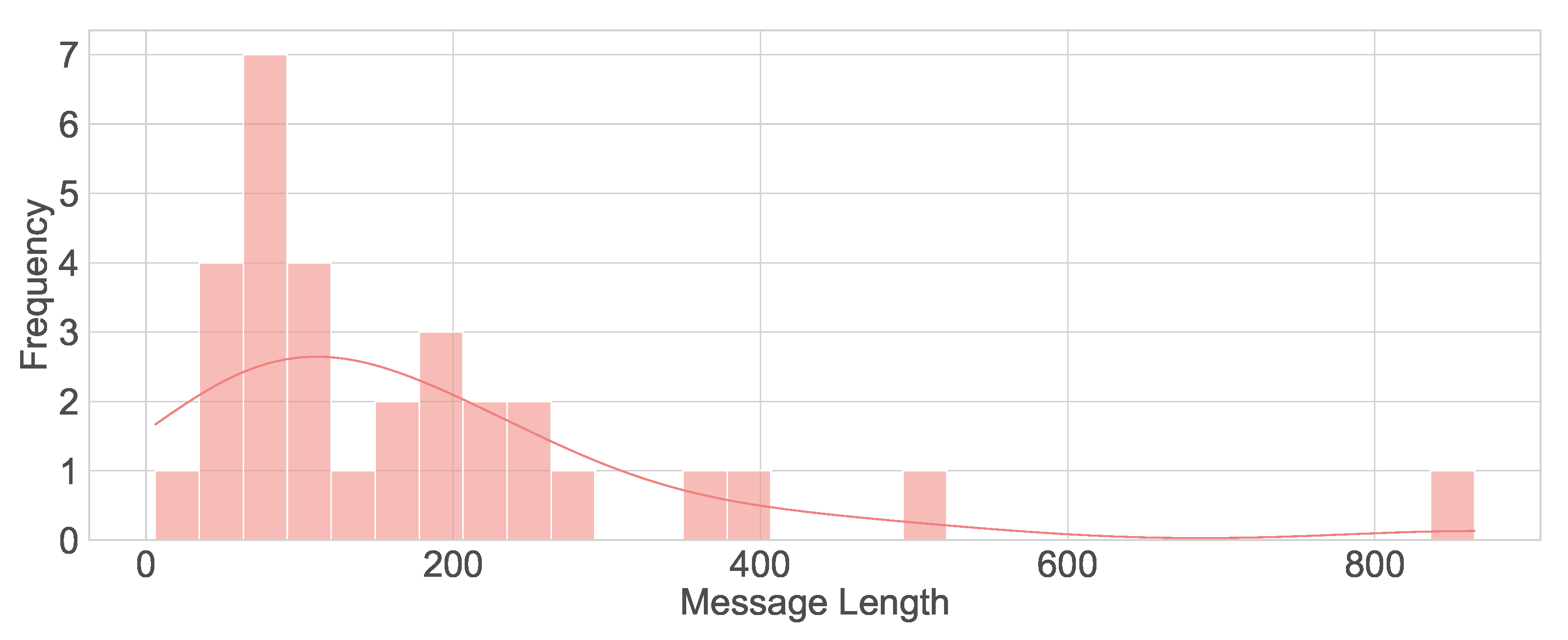

Figure 4. The message length’s histogram shown the majority messages are under 200 characters (

Figure 5) and the multi-label message classes against their true labels are shown in

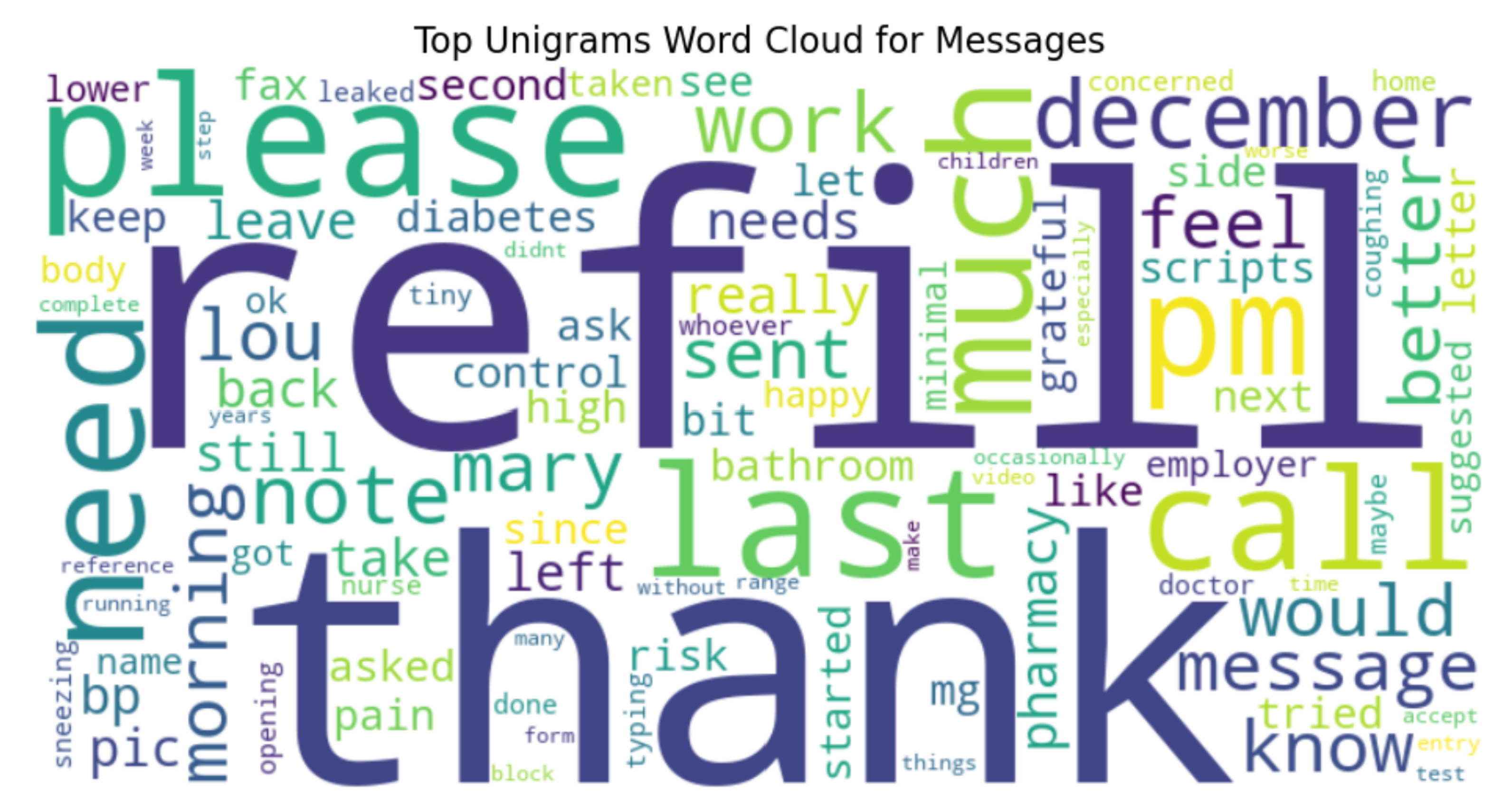

Figure 6 reveals that some of messages fall into more than one category. A word cloud depicts the most frequent words in these messages as shown in

Figure 7.

Dataset Statistics:

3.2. Prompting Approach

In this study, we adopted two primary strategies for leveraging large language models (LLMs) to classify patient messages: few-shot prompting and fine-tuning. These approaches were selected based on their practicality, effectiveness, and compatibility with the available dataset.

Few-Shot Prompting: We used few-shot prompting by providing the model with a small set of example messages and their corresponding labels. These examples helped guide the LLM in understanding the structure and context of patient communications, enabling it to generalize to new, unseen messages. This method proved useful for tasks such as urgency detection and multi-label classification, without requiring any additional model training. Few-shot prompting was particularly effective in improving classification consistency for messages with informal language or multiple intents.

Fine-Tuning: To further enhance performance, we fine-tuned GPT-4o using a set of de-identified patient messages labeled by doctors. The fine-tuning process was conducted within a secure Azure OpenAI environment to ensure HIPAA compliance and data privacy. This allowed the model to learn hospital-specific communication patterns and domain terminology. Fine-tuning significantly improved classification accuracy, particularly for multi-label and nuanced categorization tasks.

In summary, we focused on few-shot prompting for its rapid adaptability and fine-tuning for its ability to deeply tailor the model to our dataset. This combination allowed us to effectively address the complexity of hospital message classification.

3.3. Model Comparison and Selection

To evaluate the effectiveness of different LLMs in hospital message classification, we tested three key models, each with a distinct pretraining focus:

BioBERT [

11] – A biomedical domain adaptation of BERT, pre-trained on PubMed abstracts and PMC full-text articles. It has been widely used in medical NLP tasks such as named entity recognition and relation extraction.

ClinicalBERT [

12] – A model adapted from BERT, further pre-trained on MIMIC-III clinical notes, making it specialized for handling electronic health record (EHR) data.

GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024) [

20] – The latest multimodal generative model capable of understanding and processing text with a broader, generalized training dataset, spanning medical, technical, and conversational domains.

Each model was tested in a few-shot setting, meaning no additional fine-tuning was performed before evaluation as illustrated in

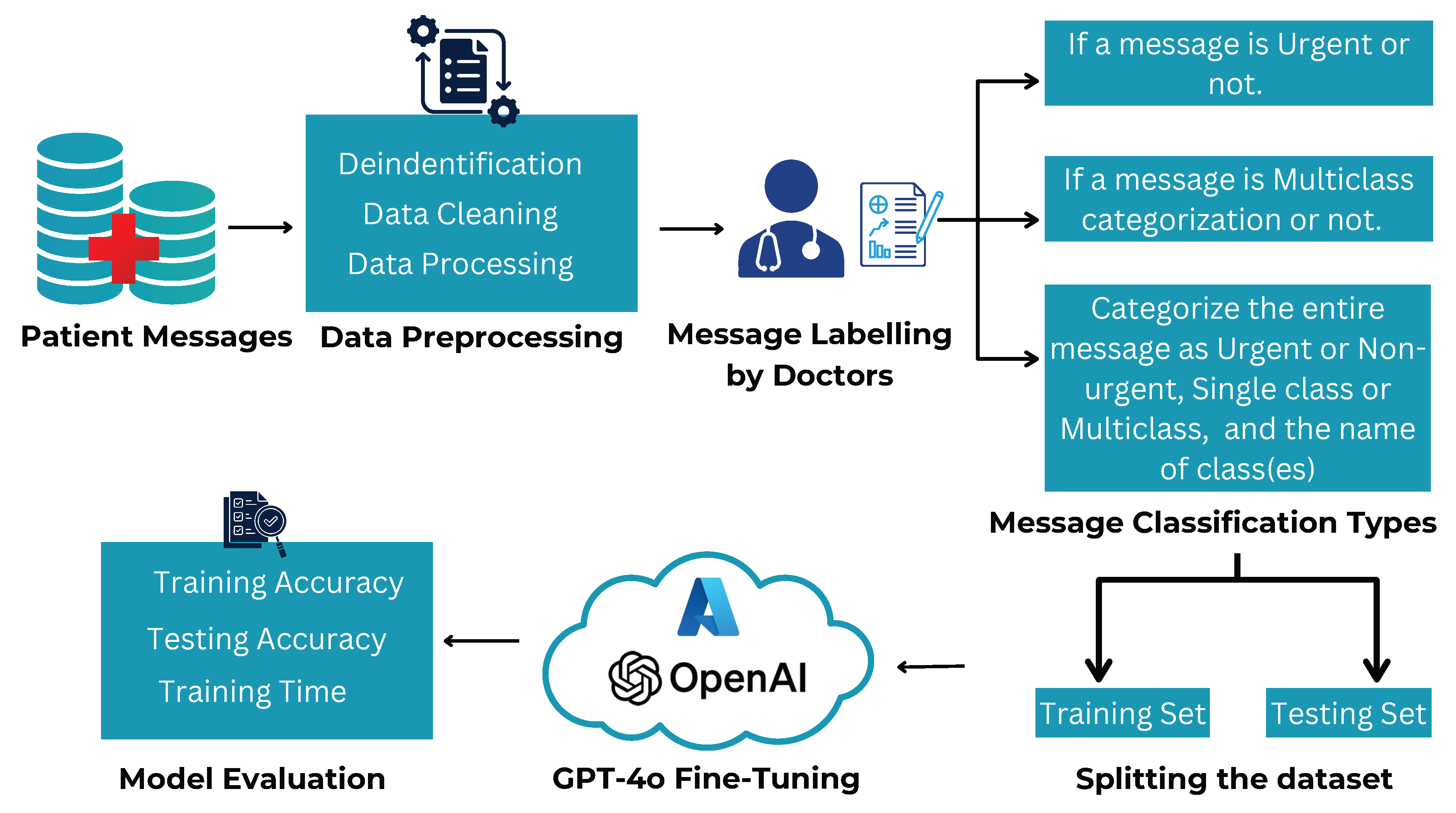

Figure 2. This approach was chosen to assess their out-of-the-box capabilities in classifying real-world hospital messages. Due to hospital security and compliance requirements, BioBERT and ClinicalBERT could not be fine-tuned externally, whereas GPT-4o was fine-tuned within the hospital’s secure Azure OpenAI cloud as shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Few-shot message classification by BioBERT, ClinicalBERT, and GPT-4o in a HIPPA complaint environment.

Figure 2.

Few-shot message classification by BioBERT, ClinicalBERT, and GPT-4o in a HIPPA complaint environment.

Figure 3.

Few-shot fine-tuned message classification by GPT-4o in a HIPPA complaint environment.

Figure 3.

Few-shot fine-tuned message classification by GPT-4o in a HIPPA complaint environment.

Figure 4.

Boxplot of message types.

Figure 4.

Boxplot of message types.

Figure 5.

Histogram of message lengths.

Figure 5.

Histogram of message lengths.

Figure 6.

Multi-label class distribution.

Figure 6.

Multi-label class distribution.

Figure 7.

Word cloud of common terms in messages.

Figure 7.

Word cloud of common terms in messages.

3.3.1. Factors Affecting Model Performance

Despite being trained on domain-specific data, BioBERT and ClinicalBERT struggled with multi-label classification. Several factors likely contributed to this outcome:

Pretraining Focus: BioBERT was trained mainly for biomedical literature processing, making it effective for medical terminology but less adaptable to informal, multi-intent patient messages.

Data Domain Limitations: ClinicalBERT was trained on structured EHR notes, which differ significantly from the short, often unstructured nature of patient communication in hospital portals.

Contextual Understanding: Both models rely on BERT-style masked language modeling, which, while effective for extraction-based NLP tasks, may be less suited for complex, multi-class classification without additional fine-tuning.

In contrast, GPT-4o significantly outperformed both models in the few-shot setting, achieving urgency classification accuracy as high as of 0.807 and multi-class classification accuracy around 0.588.

GPT-4o’s stronger performance can be attributed to its larger and more diverse training corpus, its multimodal capabilities, and its ability to generalize well across domains without requiring domain-specific pretraining.

3.3.2. Selection for Fine-Tuning

Given its superior performance without fine-tuning, GPT-4o was selected for further fine-tuning on the hospital’s private Azure OpenAI cloud infrastructure. This setup ensured compliance with HIPAA regulations, allowing GPT-4o to learn from real patient interactions while maintaining data privacy and security. The fine-tuning process aimed to refine its classification accuracy, adapting it to the hospital’s unique messaging patterns and patient communication style.

Fine-Tuning Environment: Fine-tuning was conducted within the hospital’s secure cloud environment, leveraging Azure OpenAI services. This setup allowed GPT-4o to adapt to domain-specific terminology and patient communication styles, further improving its classification accuracy. Models were fine-tuned on the hospital dataset. The experimental setup included a 70%-15%-15% training-validation-test split, with metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC used for evaluation. The framework used involved the following steps:

Urgency Classification: Each message was classified as either Urgent or Non-Urgent.

Category Type: Messages were identified as involving either a Single or Multiple category.

-

Relevant Categories: Messages were further classified into one or more of the following categories:

- -

Appointment

- -

Referral Question

- -

Request an Update to my Medical Record

- -

Visit Follow-Up Question

- -

General Question

- -

Therapy Question

- -

Refills

- -

Other

- -

Test Results Question

- -

Prescription Question

3.4. Fine-Tuning and Non-Fine-Tuning Approaches

GPT-4o was tested with and without fine-tuning. Combined with few-shot prompting, fine-tuning yielded the best results. Fine-tuned LLMs achieved over 90% accuracy across categories, outperforming baseline models. Few-shot prompting improved contextual understanding and classification consistency. Fine-tuned GPT-4 and few-shot prompting demonstrated superior performance in multi-category classification tasks.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Performance Metrics and Their Significances

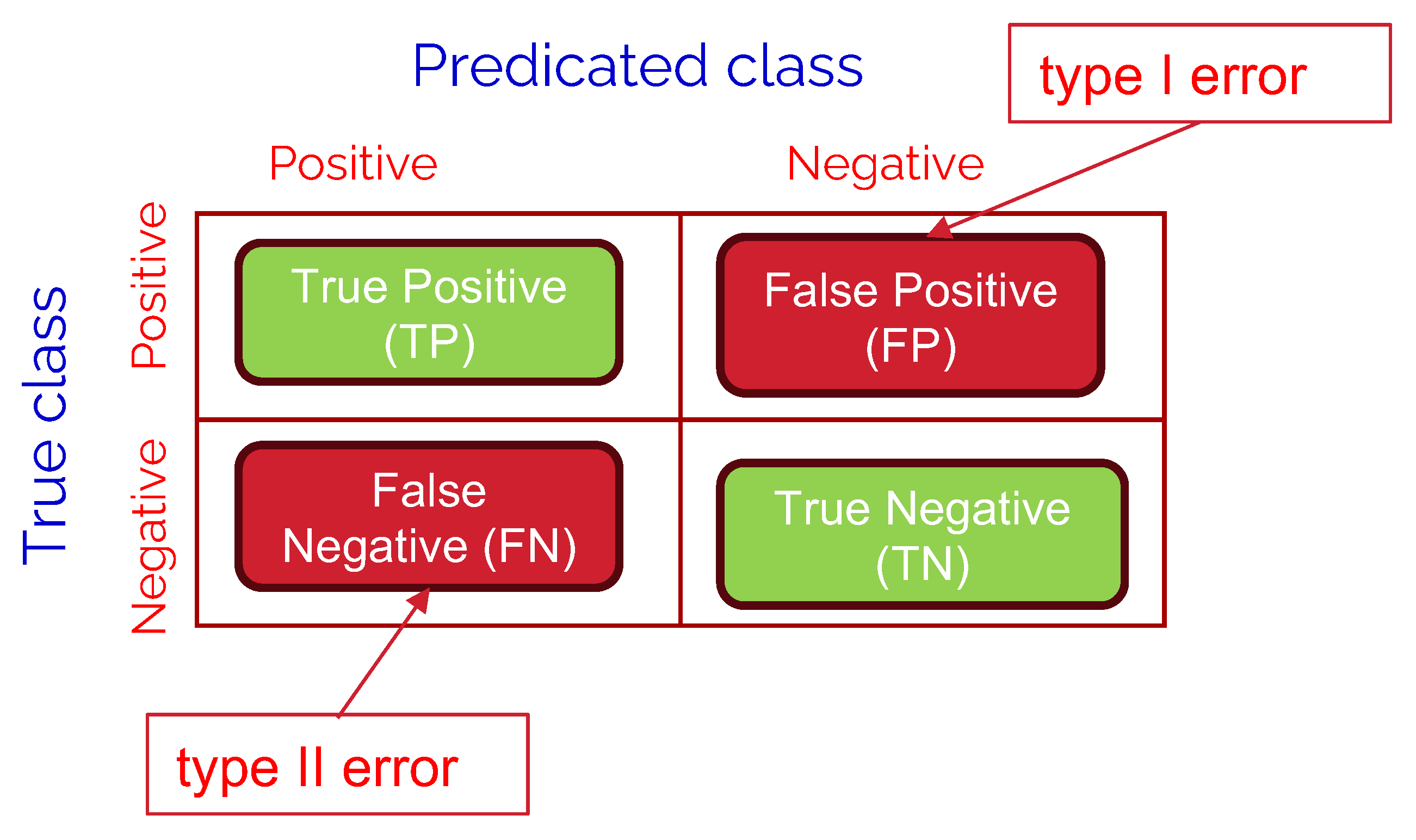

In this section, we are going to discuss the used performance metrics in evaluating the comparative performance of the studied LLM models. A confusion matrix is a tool used to measure the performance of classification models by comparing actual vs. predicted values. Each entry in the matrix represents the count of predictions falling into four key categories:

True Positives (TP): Correctly predicted positive cases (e.g., urgent messages classified as urgent).

True Negatives (TN): Correctly predicted negative cases (e.g., non-urgent messages classified as non-urgent).

False Positives (FP): Incorrectly predicted positive cases (e.g., non-urgent messages classified as urgent), also known as type I error.

False Negatives (FN): Incorrectly predicted negative cases (e.g., urgent messages classified as non-urgent), also known as type II error.

Referring to the binary classification confusion matrix as shown in

Figure 8, we define the following performance metrics:

-

Precision represents the proportion of correctly predicted positive cases (e.g., urgent messages) out of all cases predicted as positive. A high precision value indicates that the model is good at avoiding false alarms (lower FP, namely, lower type I error), which is essential in scenarios where misclassification can result in unnecessary interventions or inefficiencies.

-

Recall, also known as sensitivity or true positive rate, measures how well the model identifies actual positive cases. In the context of urgent messages, a higher recall means fewer critical cases are missed (lower FN, namely, lower type II error), ensuring that patients requiring immediate attention receive the necessary care.

-

F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced evaluation of the model’s performance when both false positives and false negatives need to be minimized.

-

Accuracy gives an overall measure of correctness but can be misleading in imbalanced datasets where one class dominates.

4.2. Performance Evaluation

To assess the effectiveness of different LLMs in classifying hospital messages, we conducted experiments under a few-shot setting before fine-tuning GPT-4o. The performance of each model was measured based on urgency classification, multi-class accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, partial match accuracy, and exact match accuracy.

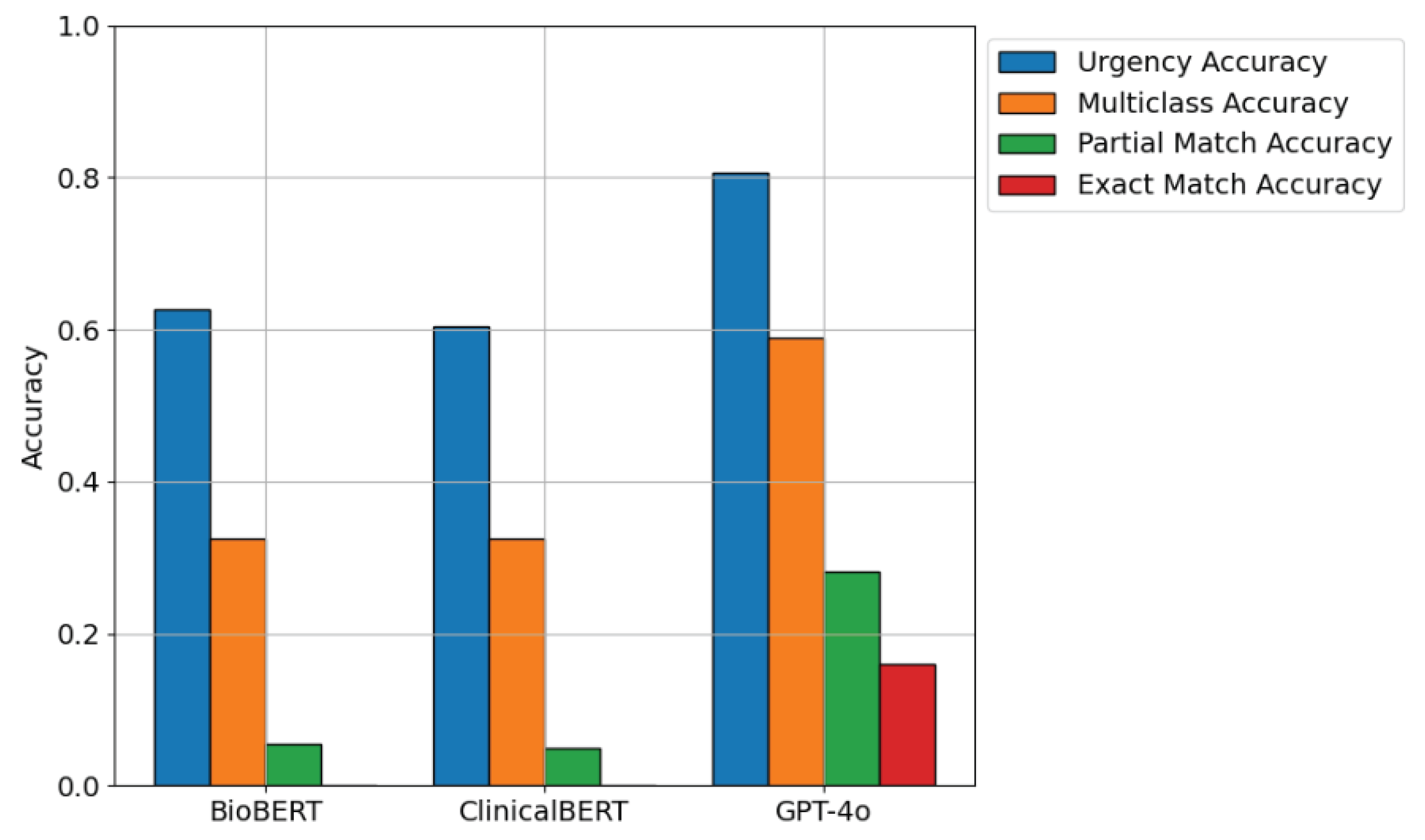

Figure 9 presents a comparative analysis of BioBERT, ClinicalBERT, and GPT-4o in a few-shot classification setting. While BioBERT and ClinicalBERT were designed for domain-specific biomedical and clinical tasks, their performance was lower in multi-class and exact match accuracy due to the informal nature of patient messages. In contrast, GPT-4o demonstrated higher accuracy across all metrics, likely due to its extensive pretraining on diverse datasets.

Table 2 and

Table 3 quantifies the performance gaps observed in

Figure 9. BioBERT and ClinicalBERT performed relatively well in multi-class classification but struggled with urgency categorization and exact match classification. These findings suggest that while domain-specific models are effective for structured medical data, they require additional fine-tuning to adapt to informal and patient-centered communication.

4.3. Impact of Fine-Tuning GPT-4o

Given GPT-4o’s superior few-shot performance, it was selected for fine-tuning within a secure hospital cloud environment (Azure OpenAI) to further enhance classification accuracy.

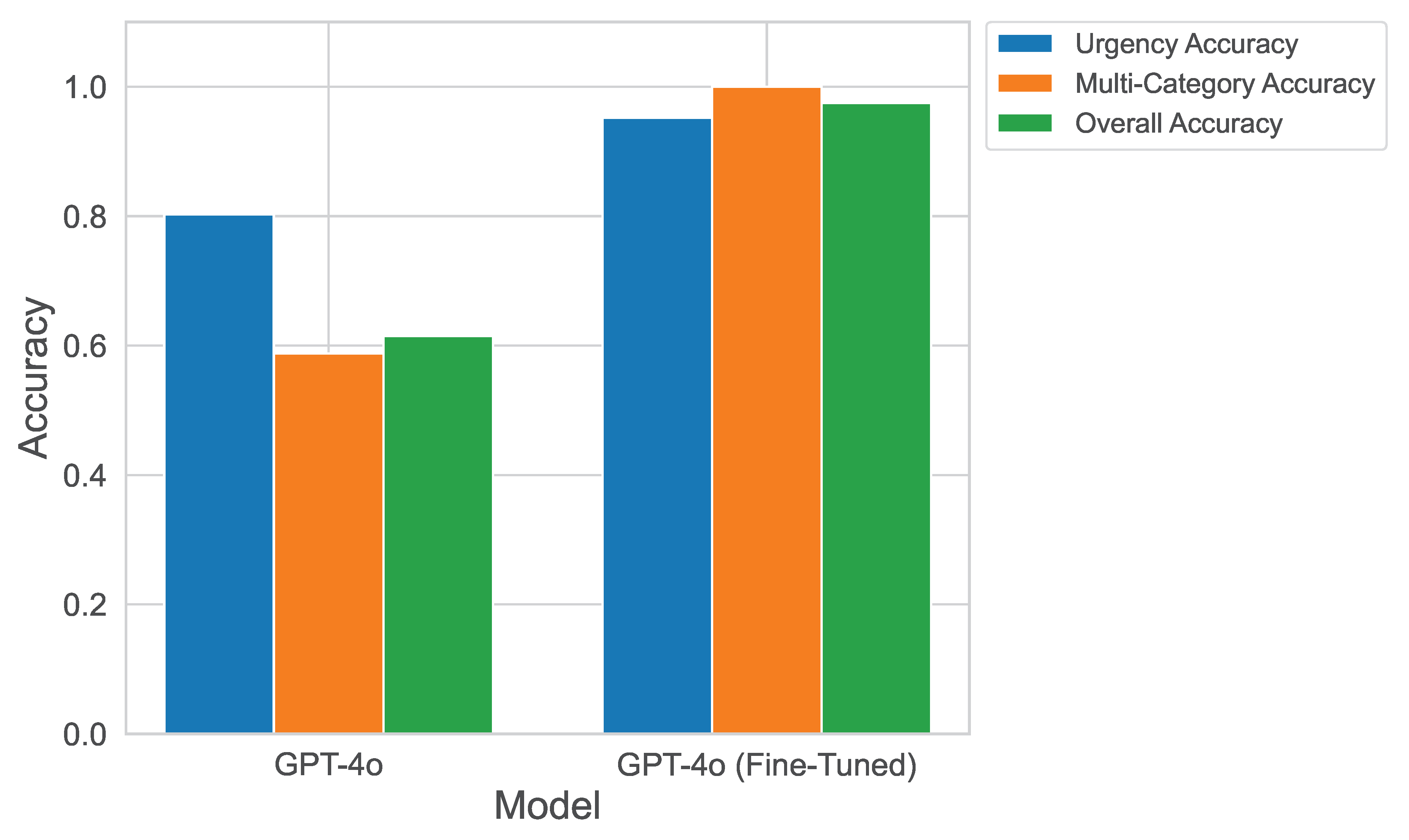

Figure 10 illustrates the improvement in GPT-4o’s classification performance after fine-tuning. Compared to its few-shot performance, fine-tuning enabled the model to better understand hospital-specific terminology, patient communication styles, and urgency nuances.

Table 5 summarizes the improvements observed after fine-tuning. The testing accuracy for multi-class categorization reached 100%, while urgency classification and full message categorization exceeded 95% accuracy. These results confirm that fine-tuning significantly enhances classification reliability in healthcare settings.

4.3.1. BioBERT vs. ClinicalBERT vs. GPT-4o

BioBERT and ClinicalBERT showed moderate performance in Urgency Classification, but struggled with multi-label classification due to their domain-specific pretraining on structured clinical notes rather than conversational messages. Their low precision suggests a high false positive rate, meaning they frequently misclassified non-urgent messages as urgent.

GPT-4o achieved significantly higher precision and recall, especially in multi-label classification, due to its broader training on diverse datasets. The improvement in F1-score confirms its balanced performance in identifying correct categories while minimizing false classifications.

The confusion matrices highlight these differences:

BioBERT and ClinicalBERT showed high recall but low precision, meaning they captured many actual urgent cases but also produced many false positives.

GPT-4o exhibited both high precision and recall, demonstrating its ability to correctly classify messages while minimizing incorrect predictions.

4.4. Implications for Hospital Message Classification

High recall is crucial for urgent messages, ensuring that no critical cases are missed.

High precision is important for non-urgent messages, preventing unnecessary escalations.

For multi-label classification, F1-score provides a balanced measure of performance, ensuring accurate categorization without excessive false positives.

4.5. Key Observations and Insights

BioBERT and ClinicalBERT performed well in urgency classification but struggled with multi-label classification due to their pretraining focus on structured clinical documentation.

GPT-4o demonstrated strong few-shot performance, highlighting its ability to generalize across medical and patient communication tasks.

Fine-tuning GPT-4o significantly improved accuracy, particularly for multi-class and exact match classification, ensuring reliable message triage.

The secure Azure OpenAI cloud environment provided a HIPAA-compliant infrastructure for fine-tuning without compromising patient privacy.

5. Discussion

LLMs demonstrated high accuracy and adaptability, reducing manual effort in message classification. Challenges include computational costs, sensitivity to biased data, and the need for domain expertise. Ethical considerations, such as secure handling of sensitive data and fairness in model predictions, are critical for deployment in healthcare.

5.1. Strengths

High accuracy and adaptability to different message categories.

Effective handling of multi-label classification tasks.

Reduction in manual effort for message classification and sorting.

5.2. Limitations

High computational cost for training and inference.

Sensitivity to biased or imbalanced training data.

Requirement of domain expertise for effective fine-tuning.

5.3. Ethical Considerations

De-identification and secure handling of sensitive patient data.

Ensuring fairness and mitigating biases in model predictions.

Need for explainability in high-stakes decision-making.

5.4. Practical Applications

Operational Efficiency : Integration with hospital management systems for automatic triage and message sorting from enormous volume of received patients’ messages. This enables healthcare workers on focusing more time on patient caring rather than message handling.

Clinical Decision Support : Flagging urgent clinical messages for immediate attention.

Patient Communication : Automated responses for frequently asked questions, enhancing patient satisfaction.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

Large language models (LLMs) have great potential in automating hospital message classification, reducing manual workload, and improving response efficiency. This study focused on classifying patients messages on EMR health care system using a number of LLMs and evaluated their performance against a number of different performance matrices. The result showed that GPT-4o outperformed other studied models (BioBERT and ClinicalBERT) due to its strong few-shot performance across multiple classification tasks.

Fine-tuning GPT-4o in a secure hospital cloud environment further enhanced its accuracy, particularly in urgency classification and multi-label categorization. The results demonstrated that:

LLMs can effectively classify hospital messages, streamlining administrative workflows and improving patient communication.

GPT-4o, even without fine-tuning, achieved strong performance, justifying its selection for further refinement.

Fine-tuned GPT-4o outperformed other models, achieving high accuracy and demonstrating adaptability to real-world hospital data.

These findings highlight the advantages of leveraging large-scale general-purpose LLMs in healthcare settings, particularly when fine-tuned with domain-specific data. To further enhance LLM-based classification in better hospital communication, patient outcomes, and operational efficiency, future research might focus on:

Implementing real-time deployment to assist clinicians and administrative staff in urgent message triage.

Developing multi-modal models that integrate structured EHR data with textual inputs for improved context understanding.

Expanding training datasets to enhance model generalization across diverse patient demographics and healthcare institutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.M.N.A. and R.F.; methodology, G.G.M.N.A. and A.S.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S., G.G.M.N.A. and R.F.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, X.X.; resources, R.F.; data curation, R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and G.G.M.N.A.; writing—review and editing, R.F.; visualization, A.S. and G.G.M.N.A.; supervision, G.G.M.N.A. and R.F.; project administration, G.G.M.N.A. and R.F.; funding acquisition, G.G.M.N.A. and R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research was funded by OSF BU Alliance IFH (Innovation for Health) project under grant number 1330007.“

Institutional Review Board Statement: Study title

[2115351-2] Automated Message Classification and Response based OpenAI System. Submission type: Response/Follow-up. Approval date: April 1, 2024. Review type: Expedited review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are unavailable on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to hospital confidentiality policies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the IFH grant between Bradley University and OSF Hospital. The authors thank the hospital administration for anonymized datasets and the data science team for preprocessing and model training support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HIPAA |

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 in the Unites States. |

| EHR |

Electronic Health Record |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| ChatGPT |

ChatGPT is a one kind of LLM [20] |

| BioBERT |

BioBERT is a one of LLM [11] |

| ClinicalBERT |

ClinicalBERT is a one kind of LLM [12] |

References

- Consulting, L. Tapping Into New Potential: Realising the Value of Data in the Healthcare Sector. https://www.ibm.com/thought-leadership/institute-business-value/report/healthcare-data, 2025. Last accessed on 05-27-2025.

- Peter, B. Jensen, Lars J. Jensen, S.B. Mining Electronic Health Records: Towards Better Research Applications and Clinical Care. Nature Reviews Genetics 2012, 13, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Chen, B. Optimizing Healthcare Delivery: Investigating Key Areas for AI Integration and Impact in Clinical Settings. preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hond, A.; et al. Guidelines and quality criteria for artificial intelligence-based prediction models in healthcare: a scoping review. npj Digital Medicine 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paucar, E.; Paucar, H.; Paucar, D.; Paucar, G.; Sotelo, C. Artificial intelligence as an innovation tool in hospital management: a study based on the sdgs. jlsdgr 2024, 5, e04089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorencin, I.; Tanković, N.; Etinger, D. Optimizing healthcare efficiency with local large language models 2025. 160. [CrossRef]

- Nashwan, A.; Abujaber, A. Harnessing the power of large language models (llms) for electronic health records (ehrs) optimization. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Doe, J. Automated Classification of Clinical Text using Machine Learning. Journal of Medical Informatics 2019, 36, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; White, S. Medical Text Classification Using Deep Learning Techniques. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2020, 45, 210–222. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.; Taylor, M. Deep Learning Models for Electronic Health Record Classification. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2021, 68, 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; So, J.; Kang, H. BioBERT: A Pre-trained Biomedical Language Representation Model for Biomedical Text Mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsentzer, E.; Murphy, J.R.; Boag, W.; Weng, W.H.; Jin, H.; Naumann, T.; McDermott, M.B. Publicly Available Clinical BERT Embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.03323, 2019; arXiv:1904.03323 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. GPT-4: OpenAI’s Multimodal Large Language Model. OpenAI Technical Report 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Kumar, A.; Smith, L. Comparing Domain-Specific and Generalist Large Language Models for Medical Text Classification. Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare 2023, 47, 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. GPT-4o: OpenAI’s latest multimodal model, 2024. Available at: https://openai.com/research/gpt-4o.

- Jianing Qiu, Meng Jiang, T.Z. Large Language Models for Medical Applications: Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023, 34, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Zhang, Xiaoyu Liu, J. P. Generative AI for Clinical Report Generation: A Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Informatics 2023, 45, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang Dai, Yujie Qian, F. L. Automating Healthcare Administrative Workflows with Large Language Models. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2023, 147, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIPAA for Professionals. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/index.html. Last accessed date: 03-14-2025.

- GPT-4o. https://openai.com/index/hello-gpt-4o/. Last accessed date: 05-21-2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).