Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Main Players in the Immune Response and Their Interaction in MS Animal Models

3. Herpesviruses Associated with Immune Function

3.1. EBV

3.2. CMV

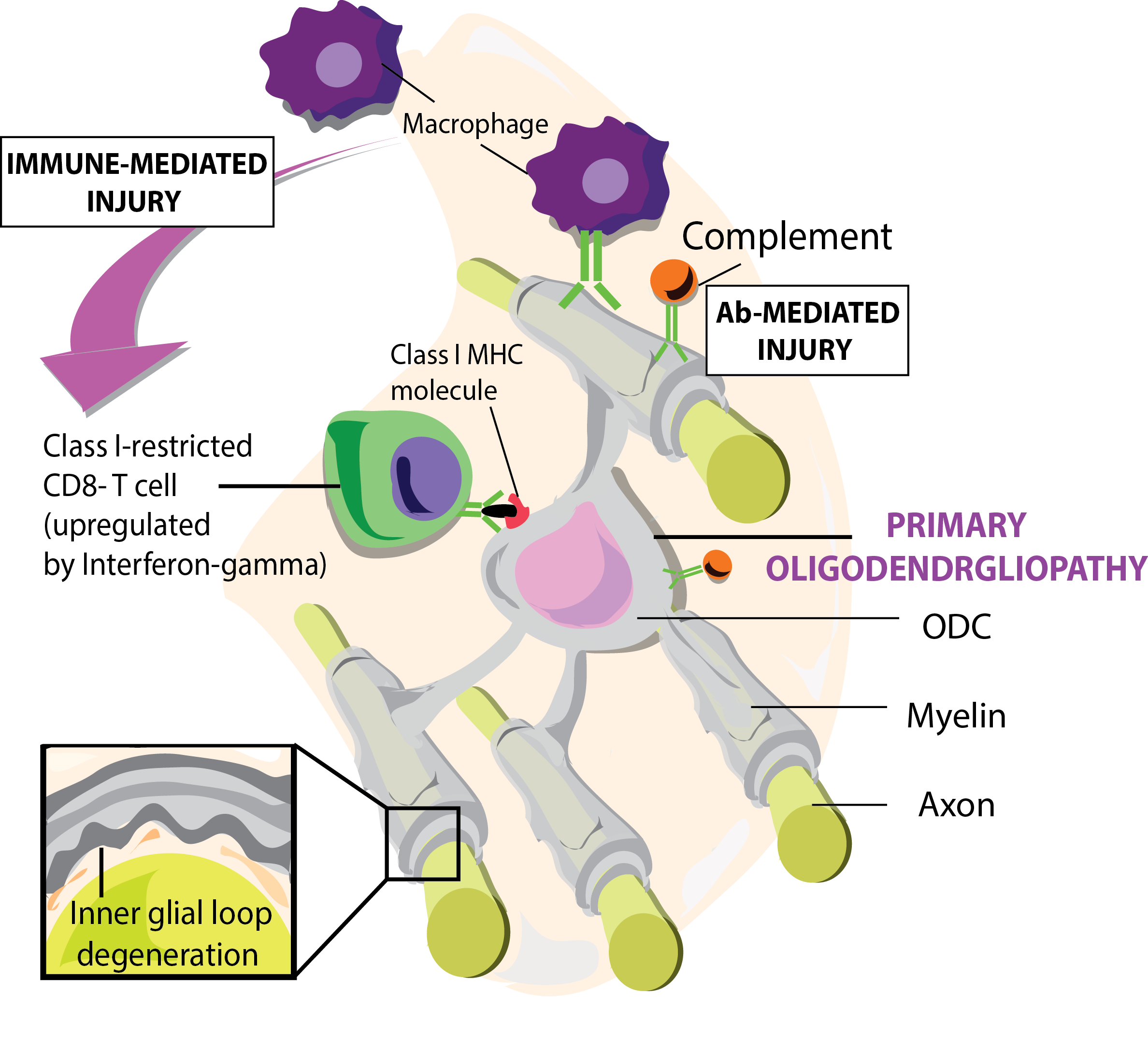

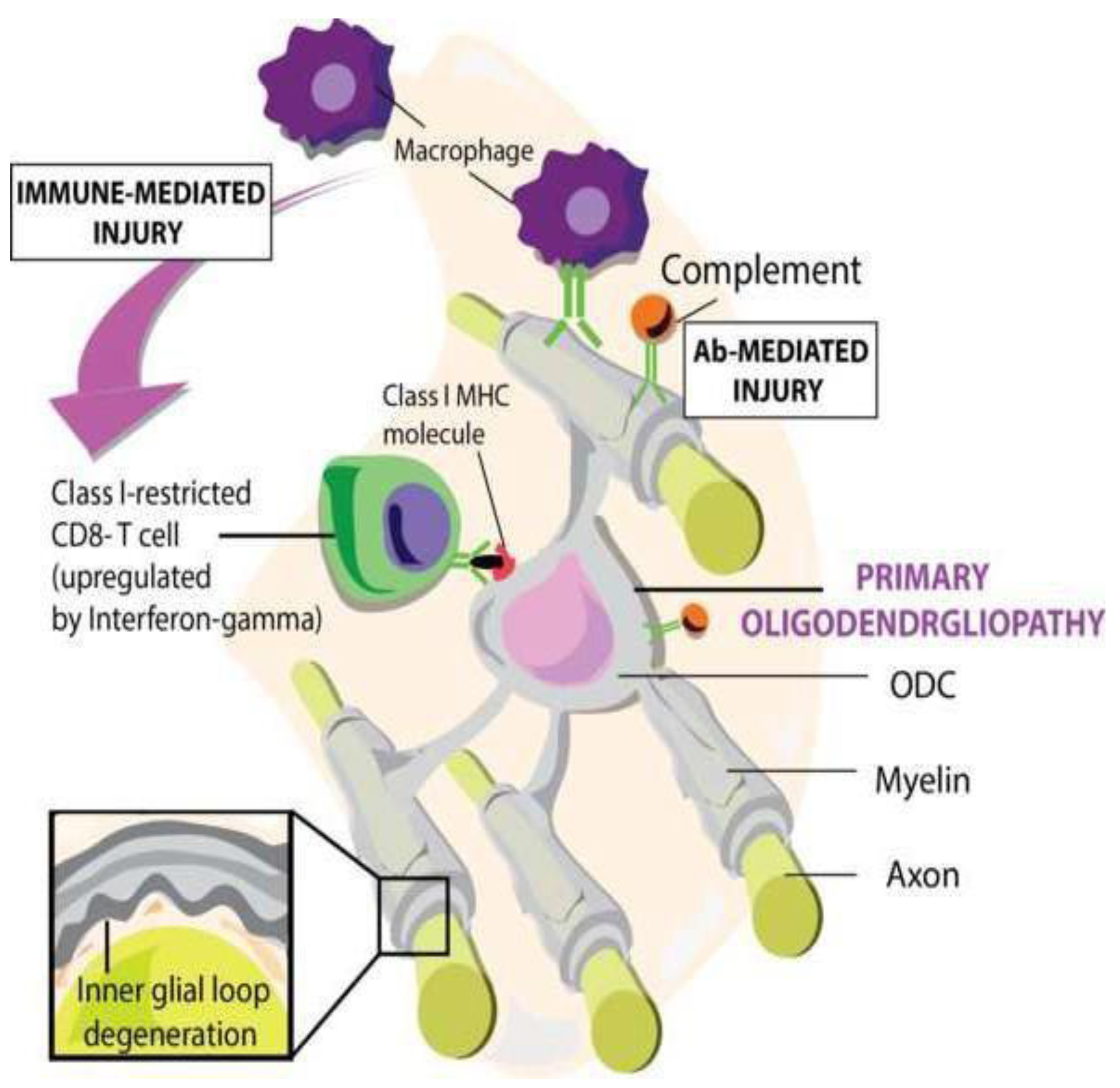

4. The Proverbial Primary Lesion

4.1. A Putative Viral Cause of Primary Lesions: HHV-6

5. MS Etiopathogenesis, a Conspiracy of Herpesviruses?

5.1. Where Does the Immune Pathogenic Process Start?

5.2. Where Do EBV-Infected B Cells Pick up Released Myelin Antigens?

5.3. Which Myelin Antigens Are Selected for Presentation to Pathogenic T Cells?

5.4. Is the Encephalitogenic MOG34-56 Peptide Differentially Processed in LCV-Infected and Non-Infected B Cells.

5.5. Which Pathogenic T Cells Respond to the MOG34-56 Peptide?

5.6. where Does T Cell Activation by EBV-Infected B Cells Occur?

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interests

References

- ‘t Hart, B.A.; Chalan, P.; Koopman, G.; Boots, A.M. Chronic autoimmune-mediated inflammation: a senescent immune response to injury. Drug Discov Today 2013, 18(7-8), 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ‘t Hart, B.A.; Dunham, J.; Faber, B.W.; Laman, J.D.; van Horssen, J.; Bauer, J.; Kap, Y.S. A B Cell-Driven Autoimmune Pathway Leading to Pathological Hallmarks of Progressive Multiple Sclerosis in the Marmoset Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Model. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ‘t Hart, B.A.; Gran, B.; Weissert, R. EAE: imperfect but useful models of multiple sclerosis. Trends Mol Med 2011, 17(3), 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ‘t Hart, B.A.; Kap, Y.S. An essential role of virus-infected B cells in the marmoset experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model. MS journal Exp Translat Clin 2017, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- ‘t Hart, B.A.; Kap, Y.S.; Morandi, E.; Laman, J.D.; Gran, B. EBV Infection and Multiple Sclerosis: Lessons from a Marmoset Model. Trends Mol Med 2016, 22(12), 1012–1024. [Google Scholar]

- ‘t Hart, B.A.; Luchicchi, A.; Schenk, G.J.; Stys, P.K.; Geurts, J.J.G. Mechanistic underpinning of an inside-out concept for autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis. Annals of clinical and translational neurology 2021, 8(8), 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablashi, D.V.; Eastman, H.B.; Owen, C.B.; Roman, M.M.; Friedman, J.; Zabriskie, J.B.; Peterson, D.L.; Pearson, G.R.; Whitman, J.E. Frequent HHV-6 reactivation in multiple sclerosis (MS) and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients. J Clin Virol 2000, 16(3), 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Lafuente, R.; Garcia-Montojo, M.; De las Heras, V.; Bartolome, M.; Arroyo, R. Clinical parameters and HHV-6 active replication in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. J Clin Virol 2006, 37 Suppl 1, S24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, M.H.; Prineas, J.W. Relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis: pathology of the newly forming lesion. Ann Neurol 2004, 55(4), 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, P.A.; Chang, William, W.L. Primate betaherpesviruses. In Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis; Arvin, A., Campadelli-Fiume, G., Mocarski, E., Moore, P.S., Roizman, B., Whitley, R., Yamanishi, K., Eds.; Cambridge, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, A.G. The origin and application of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Rev Immunol 2007, 7(11), 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasi, G.; Facchinetti, A.; Monastra, G.; Mezzalira, S.; Sivieri, S.; Tavolato, B.; Gallo, P. Protection from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE): non-depleting anti-CD4 mAb treatment induces peripheral T-cell tolerance to MBP in PL/J mice. J Neuroimmunol 1997, 73(1-2), 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjornevik, K.; Munger, K.L.; Cortese, M.; Barro, C.; Healy, B.C.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Kuhle, J.; Ascherio, A. Serum Neurofilament Light Chain Levels in Patients With Presymptomatic Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA neurology 2020, 77(1), 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornevik, K.; Munz, C.; Cohen, J.I.; Ascherio, A.; Brodin, P.; Davis, M.M.; Epstein-Barr virus as a leading cause of multiple sclerosis: mechanisms and implications. Human immune system variation. Nat Rev Neurol;Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 19(3) 17(1), 160-171 21-29. [Google Scholar]

- Brok, H.P.; Boven, L.; van Meurs, M.; Kerlero de Rosbo, N.; Celebi-Paul, L.; Kap, Y.S.; Jagessar, A.; Hintzen, R.Q.; Keir, G.; Bajramovic, J.; Ben-Nun, A.; Bauer, J.; Laman, J.D.; Amor, S.; t Hart, B.A. The human CMV-UL86 peptide 981-1003 shares a crossreactive T-cell epitope with the encephalitogenic MOG peptide 34-56, but lacks the capacity to induce EAE in rhesus monkeys. J Neuroimmunol 2007, 182(1-2), 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilli, G.; Cassotta, A.; Battella, S.; Palmieri, G.; Santoni, A.; Paladini, F.; Fiorillo, M.T.; Sorrentino, R. Regulation and trafficking of the HLA-E molecules during monocyte-macrophage differentiation. J Leukoc Biol 2016, 99(1), 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challoner, P.B.; Smith, K.T.; Parker, J.D.; MacLeod, D.L.; Coulter, S.N.; Rose, T.M.; Schultz, E.R.; Bennett, J.L.; Garber, R.L.; Chang, M. Plaque-associated expression of human herpesvirus 6 in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92(16), 7440–7444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirone, M.; Cuomo, L.; Zompetta, C.; Ruggieri, S.; Frati, L.; Faggioni, A.; Ragona, G. Human herpesvirus 6 and multiple sclerosis: a study of T cell cross-reactivity to viral and myelin basic protein antigens. J Med Virol 2002, 68(2), 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croft, M.; Bradley, L.M.; Swain, S.L. Naive versus memory CD4 T cell response to antigen. Memory cells are less dependent on accessory cell costimulation and can respond to many antigen- presenting cell types including resting B cells. J Immunol 1994, 152(6), 2675–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos, A.F.; van Meurs, M.; Brok, H.P.; Boven, L.A.; Hintzen, R.Q.; van der Valk, P.; Ravid, R.; Rensing, S.; Boon, L.; t Hart, B.A.; Laman, J.D. Transfer of central nervous system autoantigens and presentation in secondary lymphoid organs. J Immunol 2002, 169(10), 5415–5423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elong Ngono, A.; Lepetit, M.; Reindl, M.; Garcia, A.; Guillot, F.; Genty, A.; Chesneau, M.; Salou, M.; Michel, L.; Lefrere, F.; Schanda, K.; Imbert-Marcille, B.M.; Degauque, N.; Nicot, A.; Brouard, S.; Laplaud, D.A.; Soulillou, J.P. Decreased Frequency of Circulating Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein B Lymphocytes in Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. J Immunol Res 2015, 2015, 673503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelhardt, B.; Carare, R.O.; Bechmann, I.; Flugel, A.; Laman, J.D.; Weller, R.O. Vascular, glial, and lymphatic immune gateways of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 2016, 132(3), 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabriek, B.O.; Zwemmer, J.N.; Teunissen, C.E.; Dijkstra, C.D.; Polman, C.H.; Laman, J.D.; Castelijns, J.A. In vivo detection of myelin proteins in cervical lymph nodes of MS patients using ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology. J Neuroimmunol 2005, 161(1-2), 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldacre, R. Risk of multiple sclerosis in individuals with infectious mononucleosis: a national population-based cohort study using hospital records in England, 2003-2023. Mult Scler 2024, 30(4-5), 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A.D.; Mock, D.J.; Powers, J.M.; Baker, J.V.; Blumberg, B.M.; Goronzy, J.J.; Weyand, C.M.; Human herpesvirus 6 genome and antigen in acute multiple sclerosis lesions. Understanding immunosenescence to improve responses to vaccines. J Infect Dis;Nat Immunol 2003, 187(9) 14(5), 1365-1376 428-436. [Google Scholar]

- Grut, V.; Bistrom, M.; Salzer, J.; Stridh, P.; Jons, D.; Gustafsson, R.; Fogdell-Hahn, A.; Huang, J.; Butt, J.; Lindam, A.; Alonso-Magdalena, L.; Bergstrom, T.; Kockum, I.; Waterboer, T.; Olsson, T.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Andersen, O.; Nilsson, S.; Sundstrom, P. Human herpesvirus 6A and axonal injury before the clinical onset of multiple sclerosis. Brain 2024, 147(1), 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, G.; Jores, R.; Mocarski, E.S. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95(7), 3937–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, S.L.; Waubant, E.; Arnold, D.L.; Vollmer, T.; Antel, J.; Fox, R.J.; Bar-Or, A.; Panzara, M.; Sarkar, N.; Agarwal, S.; Langer-Gould, A.; Smith, C.H.; Group, H.T. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2008, 358(7), 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagessar, S.A.; Heijmans, N.; Blezer, E.L.; Bauer, J.; Blokhuis, J.H.; Wubben, J.A.; Drijfhout, J.W.; van den Elsen, P.J.; Laman, J.D.; t Hart, B.A. Unravelling the T-cell-mediated autoimmune attack on CNS myelin in a new primate EAE model induced with MOG34-56 peptide in incomplete adjuvant. Eur J Immunol 2012, 42(1), 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagessar, S.A.; Holtman, I.R.; Hofman, S.; Morandi, E.; Heijmans, N.; Laman, J.D.; Gran, B.; Faber, B.W.; van Kasteren, S.I.; Eggen, B.J.; t Hart, B.A. Lymphocryptovirus Infection of Nonhuman Primate B Cells Converts Destructive into Productive Processing of the Pathogenic CD8 T Cell Epitope in Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein. J Immunol 2016, 197(4), 1074–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagessar, S.A.; Kap, Y.S.; Heijmans, N.; van Driel, N.; van Straalen, L.; Bajramovic, J.J.; Brok, H.P.; Blezer, E.L.; Bauer, J.; Laman, J.D.; t Hart, B.A. Induction of progressive demyelinating autoimmune encephalomyelitis in common marmoset monkeys using MOG34-56 peptide in incomplete freund adjuvant. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2010, 69(4), 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagessar, S.A.; Smith, P.A.; Blezer, E.; Delarasse, C.; Pham-Dinh, D.; Laman, J.D.; Bauer, J.; Amor, S.; t Hart, B. Autoimmunity against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein is dispensable for the initiation although essential for the progression of chronic encephalomyelitis in common marmosets. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2008, 67(4), 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamei, A.; Ichinohe, S.; Onuma, R.; Hiraga, S.; Fujiwara, T. Acute disseminated demyelination due to primary human herpesvirus-6 infection. Eur J Pediatr 1997, 156(9), 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kap, Y.S.; Smith, P.; Jagessar, S.A.; Remarque, E.; Blezer, E.; Strijkers, G.J.; Laman, J.D.; Hintzen, R.Q.; Bauer, J.; Brok, H.P.; t Hart, B.A. Fast progression of recombinant human myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in marmosets is associated with the activation of MOG34-56-specific cytotoxic T cells. J Immunol 2008, 180(3), 1326–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, N.; Flugel, A. Knocking at the brain’s door: intravital two-photon imaging of autoreactive T cell interactions with CNS structures. Semin Immunopathol 2010, 32(3), 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.; Miyashita, E.M.; Yang, B.; Babcock, G.J.; Thorley-Lawson, D.A. Is EBV persistence in vivo a model for B cell homeostasis? Immunity 1996, 5(2), 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.W.; Gao, W.; Lichti, C.F.; Gu, X.; Dykstra, T.; Cao, J.; Smirnov, I.; Boskovic, P.; Kleverov, D.; Salvador, A.F.M.; Drieu, A.; Kim, K.; Blackburn, S.; Crewe, C.; Artyomov, M.N.; Unanue, E.R.; Kipnis, J. Endogenous self-peptides guard immune privilege of the central nervous system. Nature 2025, 637(8044), 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, K.K.; Brewer, J.H.; Henry, J.M.; Harrington, D.J.; Carrigan, D.R. Human herpesvirus 6 and multiple sclerosis: systemic active infections in patients with early disease. Clin Infect Dis 2000, 31(4), 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krovi, S.H.; Kuchroo, V.K. Activation pathways that drive CD4(+) T cells to break tolerance in autoimmune diseases(). Immunol Rev 2022, 307(1), 161–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, J.; Spieker, T.; Wustrow, J.; Strickler, G.J.; Hansmann, L.M.; Rajewsky, K.; Kuppers, R. EBV-infected B cells in infectious mononucleosis: viral strategies for spreading in the B cell compartment and establishing latency. Immunity 2000, 13(4), 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laderach, F.; Piteros, I.; Fennell, E.; Bremer, E.; Last, M.; Schmid, S.; Rieble, L.; Campbell, C.; Ludwig-Portugall, I.; Bornemann, L.; Gruhl, A.; Eulitz, K.; Gueguen, P.; Mietz, J.; Muller, A.; Pezzino, G.; Schmitz, J.; Ferlazzo, G.; Mautner, J.; Munz, C.; Laman, J.D.; Weller, R.O.; EBV induces CNS homing of B cells attracting inflammatory T cells. Drainage of cells and soluble antigen from the CNS to regional lymph nodes. Nature;J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2025, 8(4), 840–856. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, H.L.; Jacobsen, H.; Ikemizu, S.; Andersson, C.; Harlos, K.; Madsen, L.; Hjorth, P.; Sondergaard, L.; Svejgaard, A.; Wucherpfennig, K.; Stuart, D.I.; Bell, J.I.; Jones, E.Y.; Fugger, L. A functional and structural basis for TCR cross-reactivity in multiple sclerosis. Nat Immunol 2002, 3(10), 940–943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lanz, T.V.; Brewer, R.C.; Ho, P.P.; Moon, J.S.; Jude, K.M.; Fernandez, D.; Fernandes, R.A.; Gomez, A.M.; Nadj, G.S.; Bartley, C.M.; Schubert, R.D.; Hawes, I.A.; Vazquez, S.E.; Iyer, M.; Zuchero, J.B.; Teegen, B.; Dunn, J.E.; Lock, C.B.; Kipp, L.B.; Cotham, V.C.; Ueberheide, B.M.; Aftab, B.T.; Anderson, M.S.; DeRisi, J.L.; Wilson, M.R.; Bashford-Rogers, R.J.M.; Platten, M.; Garcia, K.C.; Steinman, L.; Robinson, W.H. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603(7900), 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibovitch, E.; Wohler, J.E.; Cummings Macri, S.M.; Motanic, K.; Harberts, E.; Gaitan, M.I.; Maggi, P.; Ellis, M.; Westmoreland, S.; Silva, A.; Reich, D.S.; Jacobson, S. Novel marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) model of human Herpesvirus 6A and 6B infections: immunologic, virologic and radiologic characterization. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9(1), e1003138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libbey, J.E.; Cusick, M.F.; Fujinami, R.S. Role of pathogens in multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Immunol 2014a, 33(4), 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libbey, J.E.; Fujinami, R.S. Viral mouse models used to study multiple sclerosis: past and present. Arch Virol 2021, 166(4), 1015–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Libbey, J.E.; Lane, T.E.; Fujinami, R.S. Axonal pathology and demyelination in viral models of multiple sclerosis. Discov Med 2014b, 18(97), 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, H.L.; Dal Canto, M.C. Chronic neurologic disease in Theiler’s virus infection of SJL/J mice. J Neurol Sci 1976, 30(1), 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Luchicchi, A.; Hart, B.; Frigerio, I.; van Dam, A.M.; Perna, L.; Offerhaus, H.L.; Stys, P.K.; Schenk, G.J.; Geurts, J.J.G. Axon-Myelin Unit Blistering as Early Event in MS Normal Appearing White Matter. Ann Neurol 2021, 89(4), 711–725. [Google Scholar]

- Luchicchi, A.; Munoz-Gonzalez, G.; Halperin, S.T.; Strijbis, E.; van Dijk, L.H.M.; Foutiadou, C.; Uriac, F.; Bouman, P.M.; Schouten, M.A.N.; Plemel, J.; t Hart, B.A.; Geurts, J.J.G.; Schenk, G.J. Micro-diffusely abnormal white matter: An early multiple sclerosis lesion phase with intensified myelin blistering. Annals of clinical and translational neurology 2024, 11(4), 973–988. [Google Scholar]

- Lyman, M.G.; Enquist, L.W. Herpesvirus interactions with the host cytoskeleton. J Virol 2009, 83(5), 2058–2066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magliozzi, R.; Serafini, B.; Rosicarelli, B.; Chiappetta, G.; Veroni, C.; Reynolds, R.; Aloisi, F. B-cell enrichment and Epstein-Barr virus infection in inflammatory cortical lesions in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2013, 72(1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzinger, P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol 1994, 12, 991–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalban, X.; Hauser, S.L.; Kappos, L.; Arnold, D.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Comi, G.; de Seze, J.; Giovannoni, G.; Hartung, H.P.; Hemmer, B.; Lublin, F.; Rammohan, K.W.; Selmaj, K.; Traboulsee, A.; Sauter, A.; Masterman, D.; Fontoura, P.; Belachew, S.; Garren, H.; Mairon, N.; Chin, P.; Wolinsky, J.S.; Investigators, O.C. Ocrelizumab versus Placebo in Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017, 376(3), 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, E.; Jagessar, S.A.; t Hart, B.A.; Gran, B. EBV Infection Empowers Human B Cells for Autoimmunity: Role of Autophagy and Relevance to Multiple Sclerosis. J Immunol 2017, 199(2), 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Moretta, L.; Romagnani, C.; Pietra, G.; Moretta, A.; Mingari, M.C. NK-CTLs, a novel HLA-E- restricted T-cell subset. Trends Immunol 2003, 24(3), 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Muhe, J.; Wang, F. Non-human Primate Lymphocryptoviruses: Past, Present, and Future. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2015, 391, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muller, L.; Di Benedetto, S. How Immunosenescence and Inflammaging May Contribute to Hyperinflammatory Syndrome in COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22(22). [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy, J.H.; Lucchinetti, C.; Rodriguez, M.; Weinshenker, B.G. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2000, 343(13), 938–952. [Google Scholar]

- Pawelec, G. Latent CMV makes older adults less naive. EBioMedicine 2022, 77, 103887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietilainen-Nicklen, J.; Virtanen, J.O.; Uotila, L.; Salonen, O.; Farkkila, M.; Koskiniemi, M. HHV-6-positivity in diseases with demyelination. J Clin Virol 2014, 61(2), 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietra, G.; Romagnani, C.; Mazzarino, P.; Falco, M.; Millo, E.; Moretta, A.; Moretta, L.; Mingari, M.C. HLA-E-restricted recognition of cytomegalovirus-derived peptides by human CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100(19), 10896–10901. [Google Scholar]

- Pietra, G.; Romagnani, C.; Moretta, L.; Mingari, M.C. HLA-E and HLA-E-bound peptides: recognition by subsets of NK and T cells. Curr Pharm Des 2009, 15(28), 3336–3344. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M. Virus-induced demyelination in mice: “dying back” of oligodendrocytes. Mayo Clin Proc 1985, 60(7), 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M.; Leibowitz, J.L.; Lampert, P.W. Persistent infection of oligodendrocytes in Theiler’s virus-induced encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol 1983, 13(4), 426–433. [Google Scholar]

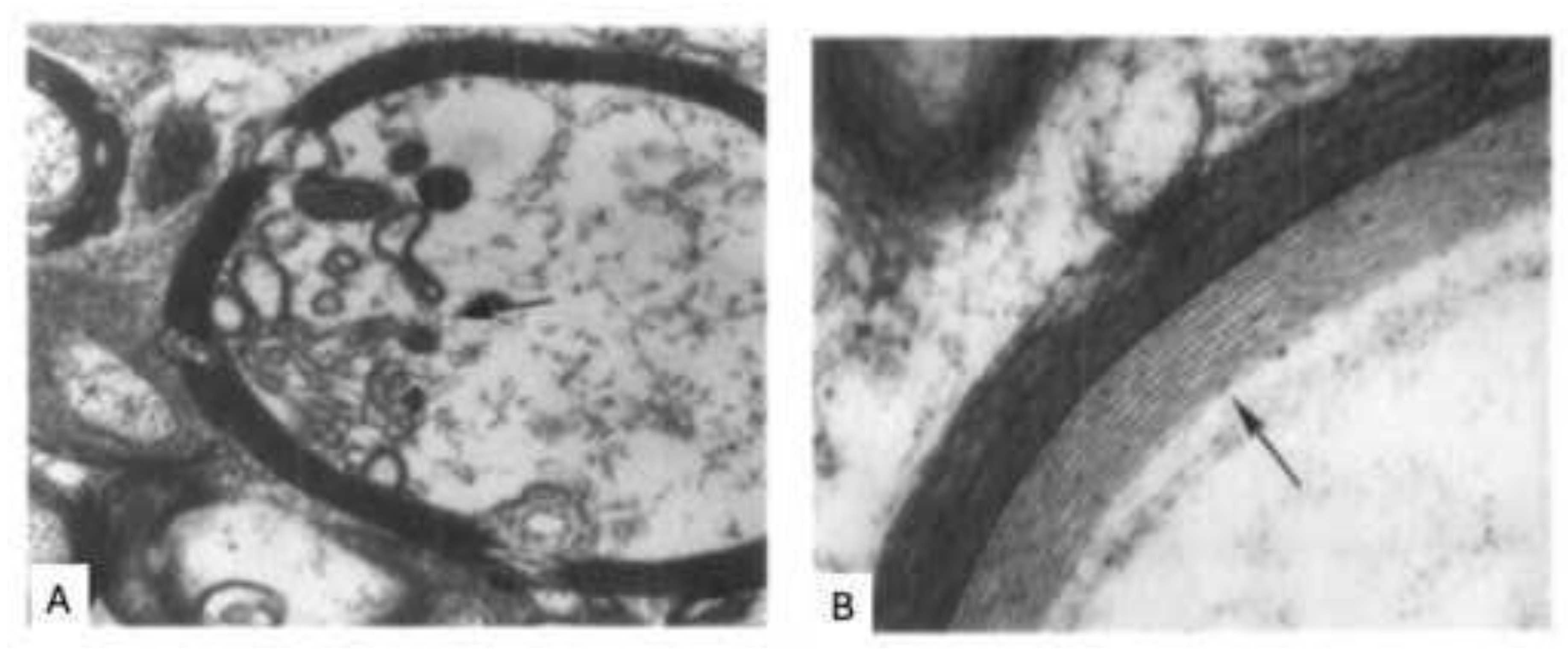

- Rodriguez, M.; Scheithauer, B. Ultrastructure of multiple sclerosis. Ultrastruct Pathol 1994, 18(1-2), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnani, C.; Pietra, G.; Falco, M.; Mazzarino, P.; Moretta, L.; Mingari, M.C. HLA-E- restricted recognition of human cytomegalovirus by a subset of cytolytic T lymphocytes. Hum Immunol 2004, 65(5), 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, M.A.; Gilardini Montani, M.S.; Gaeta, A.; D’Orazi, G.; Faggioni, A.; Cirone, M. HHV- 6A infection dysregulates autophagy/UPR interplay increasing beta amyloid production and tau phosphorylation in astrocytoma cells as well as in primary neurons, possible molecular mechanisms linking viral infection to Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866(3), 165647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saikali, P.; Antel, J.P.; Newcombe, J.; Chen, Z.; Freedman, M.; Blain, M.; Cayrol, R.; Prat, A.; Hall, J.A.; Arbour, N. NKG2D-mediated cytotoxicity toward oligodendrocytes suggests a mechanism for tissue injury in multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci 2007, 27(5), 1220–1228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarkkinen, J.; Yohannes, D.A.; Kreivi, N.; Durnsteiner, P.; Elsakova, A.; Huuhtanen, J.; Nowlan, K.; Kurdo, G.; Linden, R.; Saarela, M.; Tienari, P.J.; Kekalainen, E.; Perdomo, M.; Laakso, S.M. Altered immune landscape of cervical lymph nodes reveals Epstein-Barr virus signature in multiple sclerosis. Sci Immunol 2025, 10(104), eadl3604. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Metz, I.; Amor, S.; van der Valk, P.; Stadelmann, C.; Bruck, W. Microglial nodules in early multiple sclerosis white matter are associated with degenerating axons. Acta Neuropathol 2013, 125(4), 595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Skuja, S.; Zieda, A.; Ravina, K.; Chapenko, S.; Roga, S.; Teteris, O.; Groma, V.; Murovska, M. Structural and Ultrastructural Alterations in Human Olfactory Pathways and Possible Associations with Herpesvirus 6 Infection. PloS one 2017, 12(1), e0170071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.A.; Heijmans, N.; Ouwerling, B.; Breij, E.C.; Evans, N.; van Noort, J.M.; Plomp, A.C.; Delarasse, C.; t Hart, B.; Pham-Dinh, D.; Amor, S. Native myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein promotes severe chronic neurological disease and demyelination in Biozzi ABH mice. Eur J Immunol 2005, 35(4), 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldan, S.S.; Lieberman, P.M. Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21(1), 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriram, S.; Steiner, I. Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: a misleading model of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2005, 58(6), 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steininger, C. Clinical relevance of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with disorders of the immune system. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007, 13(10), 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stys, P.K.; Zamponi, G.W.; van Minnen, J.; Geurts, J.J. Will the real multiple sclerosis please stand up? Nature reviews. Neuroscience 2012, 13(7), 507–514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sylwester, A.W.; Mitchell, B.L.; Edgar, J.B.; Taormina, C.; Pelte, C.; Ruchti, F.; Sleath, P.R.; Grabstein, K.H.; Hosken, N.A.; Kern, F.; Nelson, J.A.; Picker, L.J. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med 2005, 202(5), 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- t Hart, B.A.; Luchicchi, A.; Schenk, G.J.; Killestein, J.; Geurts, J.J.G. Multiple sclerosis and drug discovery: A work of translation. EBioMedicine 2021, 68, 103392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorley-Lawson, D.A. Epstein-Barr virus: exploiting the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2001, 1(1), 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorley-Lawson, D.A. EBV Persistence--Introducing the Virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2015, 390 Pt 1, 151–209. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch, A.M.R.; Hummert, S.; Steyer, A.; Ruhwedel, T.; Hamann, J.; Smolders, J.; Nave, K.A.; Stadelmann, C.; Kole, M.H.P.; Mobius, W.; Huitinga, I. Ultrastructural Axon-Myelin Unit Alterations in Multiple Sclerosis Correlate with Inflammation. Ann Neurol 2023, 93(4), 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oosten, B.W.; Lai, M.; Hodgkinson, S.; Barkhof, F.; Miller, D.H.; Moseley, I.F.; Thompson, A.J.; Rudge, P.; McDougall, A.; McLeod, J.G.; Ader, H.J.; Polman, C.H. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with the monoclonal anti-CD4 antibody cM-T412: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, MR-monitored phase II trial. Neurology 1997, 49(2), 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanheusden, M.; Stinissen, P.; t Hart, B.A.; Hellings, N. Cytomegalovirus: a culprit or protector in multiple sclerosis? Trends Mol Med 2015, 21(1), 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voumvourakis, K.I.; Fragkou, P.C.; Kitsos, D.K.; Foska, K.; Chondrogianni, M.; Tsiodras, S. Human herpesvirus 6 infection as a trigger of multiple sclerosis: an update of recent literature. BMC Neurol 2022, 22(1), 57. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, J.T.; Zheng, J.; Smirnov, I.; Lorenz, U.; Tung, K.; Kipnis, J.; Wilkin, T.J.; Regulatory T cells in central nervous system injury: a double-edged sword. The primary lesion theory of autoimmunity: a speculative hypothesis. J Immunol;Autoimmunity 2014, 193(10) 7(4), 5013-5022 225-235. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Tan, D.; Piao, H. Myelin Basic Protein Citrullination in Multiple Sclerosis: A Potential Therapeutic Target for the Pathology. Neurochem Res 2016, 41(8), 1845–1856. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, T. Human herpesvirus 6 infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Br J Haematol 2004, 124(4), 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaguia, F.; Saikali, P.; Ludwin, S.; Newcombe, J.; Beauseigle, D.; McCrea, E.; Duquette, P.; Prat, A.; Antel, J.P.; Arbour, N. Cytotoxic NKG2C+ CD4 T cells target oligodendrocytes in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2013, 190(6), 2510–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).