1. Introduction

Floods caused by dam failure or dam breaching represent a hydrological phenomenon of great relevance due to their potential to generate flood peaks significantly greater than those caused by natural events such as intense rainfall [

1]. Throughout history, dams have failed due to different events or loading conditions [

2]. Generally, most documented dam and levee failures are often linked to exceedances of design water levels according to the United States Army Corps of Engineers [

3]. In addition, the scientific community has identified other types of failures, such as piping and internal filtration in the dam inner structure, which results in a piping process [

4]. Although dam-break flood hydrographs calculated for these failures usually have lower values than those produced by exceeding the water level, they are still significantly higher than the values generated by discharge through the spillway or the emergency flood drains [

4].

Over the past 100 years, there have been around 200 dam failures, resulting in more than 30,000 deaths [

2,

5]. One example was the failure of the Vaiont Dam in Italy, where 2,600 lives were lost [

2]. Another recent dam failure event due to exceeding storage capacity occurred in Derna, Libya, where more than 11,000 people lost their lives [

5].

Although a time-based analysis shows that the frequency of large dam failures has decreased by a factor of four over the past 40 years, dam failure events continue to occur with significant frequency [

6]. Given the high risk that dam failure poses to nearby communities, studies based on mathematical simulation are often required for risk assessment of new construction. These studies include an assessment of how the new construction would affect river flows, its banks, and floodplains [

1,

7]. According to Bellos

, et al. [

8] dam breach analyses are divided into two submodels: (a) the dam breach submodel, which is responsible for producing the flood hydrograph, and (b) the hydrodynamic submodel, which uses the flood hydrograph to determine flood peaks and maximum water depths downstream of the dam.

Studies have developed equations to estimate the size of a dam breach or failure (width, slope, eroded volume, etc.), as well as failure time. These equations were derived from data obtained from earth dams, dams with impermeable cores (e.g., clay, concrete, etc.), and rockfill dams, so they are not directly applicable to concrete dams or earth dams with concrete cores [

3]. Notable works in this area include Froehlich David [

9], y Froehlich David [

10], which performed multiple linear regressions to develop an equation that predicts the peak discharge following an earth dam failure. In 2008, the same presented an improved mathematical expressions based on 74 data points of dam failures (both piping and overtopping), characterizing the phenomenon and analyzing the uncertainty in predicting peak flows and water levels by using Monte Carlo simulations [

11]. In addition, the author recommended caution with the results, suggesting their application in situations with a low probability of human fatalities and low potential for property damage. Other authors Xu and Zhang [

12], have presented empirical equations to predict dam failure parameters based on 182 failure cases. This study showed the importance of dam erodibility in predicting failure, along with the reservoir shape coefficient and failure mode. In addition, they recommended a multiparameter nonlinear regression model where two case studies are included to demonstrate the applicability of the developed models. Other proposed models include MacDonald y Langridge-Monopolis (1984) and Van Thun y Gillete (1990), which can be found in [

13]. Peramuna

, et al. [

14] reviewed the techniques used in traffic modeling of the flood generated by the phenomenon and explored the different one-dimensional hydrodynamic models (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) hydrodynamic models to simulate the propagation of the flood. USACE [

7] explored advantages, disadvantages and differences between these simulations and suggests 2D modeling for some cases, since it can produce better results than 1D modeling.

A well-known tool for flood analysis is the Hydrologic Engineering Center's River Analysis System (HEC-RAS) model. It has been used to analyze water flow (Socas

, et al. [

15], and to determine floodplains, and design hydraulic engineering solutions such as dam breach studies [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In Albu et al. (2020) HEC-RAS was used to model a dam breach in a mountainous area, highlighting the importance of topographic features in flood propagation. Meanwhile, Marangoz & Anilan (2022) focused on simulating partial dam failures, demonstrating how different dam breaching configurations affect flood dynamics. [

21] discusses a management system designed for dam-break hazard mapping using MIKE-21 in complex basin environments. It outlines methodologies for data integration and simulation of dam failure scenarios, which are crucial for generating hazard maps. The research emphasizes the importance of establishing a database for dam-break hazard mapping and spatializing hydrological calculations to create effective flood hazard maps. Ongdas et al. (2020) applied HEC-RAS in an urban context, assessing the impact of dam failure in densely populated areas. The results helped identify critical areas for the implementation of mitigation strategies. This provided valuable information for designing containment and protective structures, highlighting the importance of integrating urban planning with flood management. Another discussion highlights the use of 2D hydraulic models for producing flood hazard maps [

22]. Pilotti et al. (2020) explored the model's sensitivity to different hydraulic and terrain parameters, providing a framework to improve simulation accuracy and to reduce uncertainty in results. Thus, the use of HEC-RAS allows for the development of multiple failure scenarios (overtopping or piping), by varying parameters such as the size of the dam breach, the initial conditions of the reservoir, and the topographic characteristics of the valley. These capabilities are vital for risk assessment and hazard management under potential dam failure.

Cuba has faced unique challenges in dam management due to its geography and tropical climate. According to the Cuban National Institute of Hydraulic Resources (INRH in Spanish), a total of 242 dams have been counted, 238 of which are earth dams, and more than 200 of which were built between 1960 and 1980 [

23]. Due to frequent slope failures, several authors [

24,

25,

26] have studied the influence of unsaturated soil permeability on slopes, and slope stability during rapid drawdown in earth dams with partially saturated soils. In addition, the occurrence of seismic phenomena on the east side of the island has also been observed by Urquiza-López

, et al. [

27] in the area, even without events that endanger the mechanical or structural integrity of the dam. Despite the documentation on the problems of Cuban´s earth dams, studies on flood failure and catastrophic flow events are not well documented. These is a need to update methodologies and to provide helpful information to local authorities. The only guideline for calculating time and dam breach parameters for Cuba is the Cuban Standard NC 974 2013. However, this standard does not offer information on the outflow hydrograph, which is essential for assessing the magnitude of the impact of the failure over time. The absence of this information hinders the understanding of risk involving these events, as well as the ability to prepare comprehensive strategies aimed at minimizing the impact of disasters. In addition, the impact of the phenomenon on a regional scale has not been quantified either, although Stucchi

, et al. [

28] and Socas, González, Marín, Castillo-García, Jiménez, da Silva and González-Rodríguez [

15] reported flooding events due to rainfall episodes, these conditions are not similar to dam failure events.

The primary goal of this study was to create a comprehensive hazard map for a potential breach of the Alacranes Dam in Villa Clara, Cuba, using the HEC-RAS software and a 2D downstream flow mode. This study provides useful information for urban planners of how to simulate flood scenarios with a high degree of accuracy and detail for preparing a strategy for early warning systems and evacuation routes to prevent human losses.

3. Results

After running the simulation for the 13 potential dam failure scenarios, the most relevant parameters were extracted in order to emphasize the comparison between scenarios. The most relevant parameters involved (a) TFA, (b) MWD at Sagua Road Bridge (CP1), (c) MWV at Sagua Road Bridge (CP1), (d) FAT from the time the breach occurs, until the flood peak reaches El Triunfo Bridge (CP2), and enters the floodplain downstream to Sagua La Grande, (e) RET; (f) the total time of flooding Sagua La Grande city (TTF), and (g) AWV at El Triunfo Bridge (

Table 3).

The results of the comparative analysis between the different dam failure scenarios indicated that the total flooded area varies considerably between the scenarios, with the HEC-RAS physical model (Scenario 13) showing the largest affected area with 604.6 km2, while Von Thun and Gillette (1990) A* (Scenario 9) from piping presented the smallest flooded area, with 501.7 km2; this range shows the differences in methodologies and their impact on the magnitude of the flooded areas. Likewise, the maximum water depth in CP1 varied notably with the HEC-RAS physical model reaching 12.47 m, in contrast to the Von Thun and Gillette (1990) B* from piping that reports 8.58 m (Scenario 10). These values indicated the potential severity of the flood depending on the scenario considered. The maximum water velocity and flood arrival time also showed a wide variability of FAT between 1.33 h and 3.33 h, this range is crucial for emergency response planning.

In terms of average water velocity, the HEC-RAS model (Scenario 13) predicted values of 3.21 m/s, implying a significant destructive potential compared to the channel erosion velocities specified in Te Chow and Saldarriaga [

34]. Overall, the consistency of results across different methods and models emphasized the importance of considering multiple approaches for an accurate and robust assessment of dam failure hazard.

Table 4 shows the results related to dam breach formation such as: average breach width, time to failure, total duration of each simulation, error in estimating the total generated volume, and maximum peak flow during the breach. It was observed that the widths of the breach base vary significantly, from 85 m to 350 m. In the case of the overtopping scenarios, it should be noted that the average breach width value calculated in NC 974-2013 for the Alacranes Dam was 250 m, being within the range of values obtained, and the breach development times ranged from 0.40 h to 11.88 h, while in the NC standard the time obtained was 6.2 h. The overall volume accounting error was generally low, with values from 0.004% to 2.35%. Maximum flows (Q

max) also showed wide variability, with values from 6,860 m³/s to 35,726 m

3/s. For all scenarios, the Courant coefficient remained constant between 1 and 0.45. These results reinforce the conclusion of including several types of analysis in these studies.

The 13 scenarios analyzed revealed the exposure of buildings to backwater flooding.

Figure 6 shows the saturation of the floodplain with floodwater, highlighting Scenario 13 as the most critical predicted by the HEC-RAS DL Breach physical model. In addition,

Figure 6 shows the city of Sagua la Grande, a populated town located downstream the dam. Both averaged and maximum depths were significant (≤10 m) due to the greater destructive potential of flood waves in deeper water layers

A relationship was found between the maximum break discharge variables Qmax and the Total flooded area (TFA) with an R

2 of 0.90. Despite the limitations from establishing this relationship from only 13 scenarios, the equation that relates to both variables was:

Between flow rates of 7,000 m3/s and 35,000 m3/s, by applying this potential equation it was found that the TFA would range between 500 km2 and 600 km2. The most critical simulated scenario involved the formation of a 350 m gap in just 0.67 h (Scenario 13).

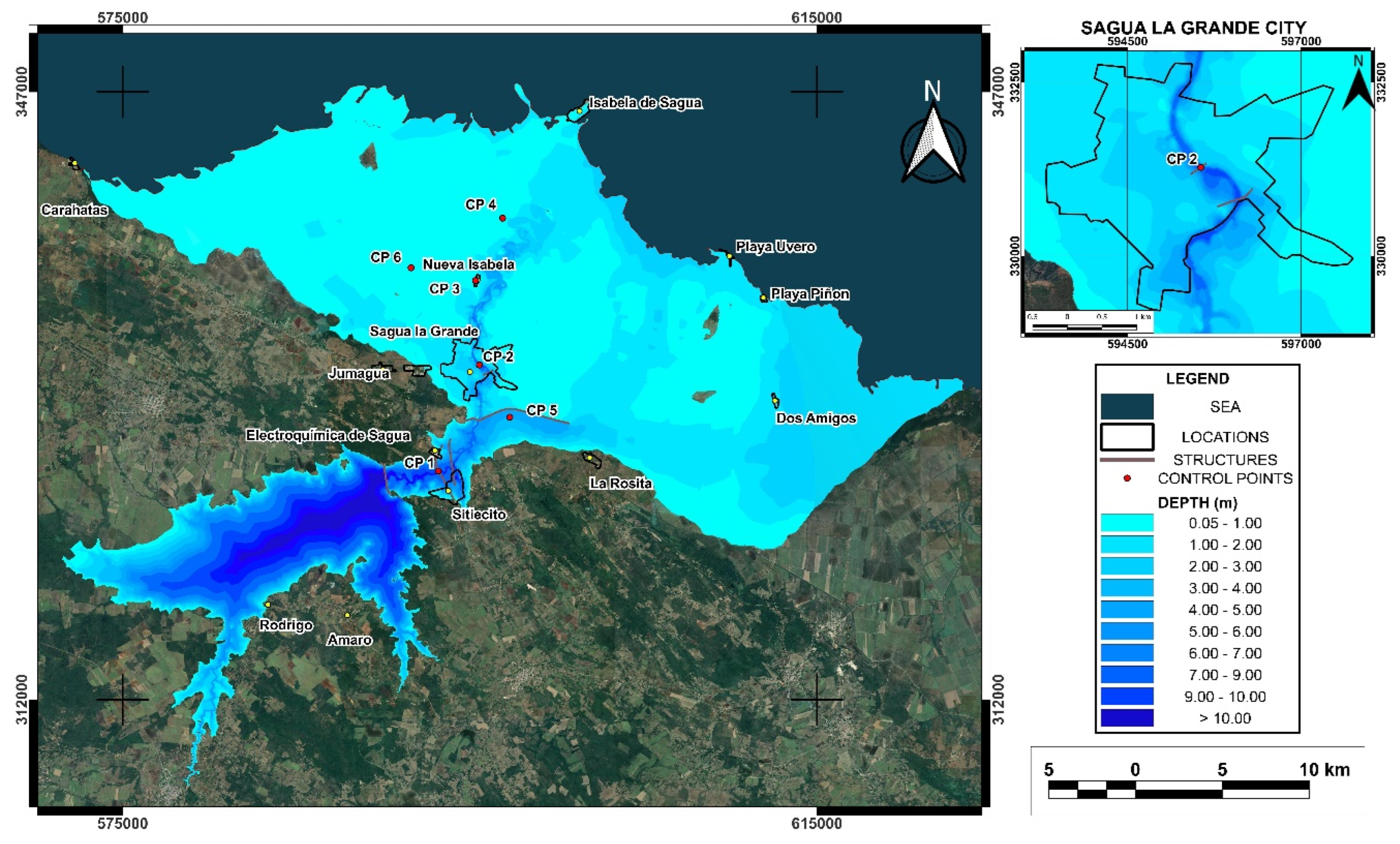

Figure 6.

The Alacranes reservoir flood map for the event of a dam failure obtained for Scenario 13. To the right is the city of Sagua la Grande, with CP 2 marked in the center.

Figure 6.

The Alacranes reservoir flood map for the event of a dam failure obtained for Scenario 13. To the right is the city of Sagua la Grande, with CP 2 marked in the center.

Figure 7 shows the velocity map obtained from the simulation of Scenario 13 (see Video SI1). Water flow presented erosive velocities between 3 m/s and 5 m/s near structures such as bridges and protective dikes. The analysis at different CP and at the flood protection structures known as Puertas de Sagua allowed to establish that a dam breach greater than 10,000 m

3/s during the peak of the flood would overflow these protective structures. If the cause of a dam failure were piping occurs, there is a probability that the overflow threshold of these dikes could not be reached. However, if this threshold were exceeded, the flood would overflow these protective structures. The coastline would be affected for an estimated length of 105 km, and several settlements and communities within the flood plain would be somehow impacted. It was preliminarily estimated that more than 49,000 population could be exposed to this risk, affecting residents mainly in the city of Sagua La Grande (38,773 inhab.), as well as in the towns of Isabela de Sagua (2,963 inhab.), Sitiocito (3,871 inhab.), La Rosita (1,635 inhab.), Nueva Isabela (980 inhab.), Dos Amigos (289 inhab.), Playa Uvero (200 inhab.), Playa Piñón (24 inhab.) Caharatas (633 inhab.), among other villages and isolated individual homes (population data were obtained from the Cuban Collaborative Encyclopedia (EcuRed) [

38].

Figure 8 shows the hazard map developed for the study area with six different color levels defining red as extreme risk, yellow as severe risk, light green as significant risk, dark green as moderate risk, light blue as caution, and dark blue as low risk. The simulation revealed that, in the event of dam failure, the areas adjacent to the reservoir will experience significant flooding, affecting both critical infrastructure and local communities. The areas identified as being at extreme risk are concentrated in the lower valley, where the city of Sagua la Grande, and towns such as Sitiecito, Nueva Isabela, Isabela de Sagua, Dos Amigos, Playa Piñon, and Playa Uvero are located. This finding is consistent with previous studies indicating that topography directly influences water propagation following a structural failure of the dam. It is important to emphasize that the city of Sagua la Grande, with a population of 38,733, would be one of the most affected areas, as it is in the severe to extreme risk classification zone. Likewise, the town closest to the dam, Sitiecito, is in an area with this same hazard classification. Identifying these areas allows for prioritizing mitigation actions, such as creating evacuation routes and implementing early warning systems, which could reduce human loss and property damage.

Table 5 shows the percentage of urban areas near the reservoir along with their flood hazard classification. The city of Sagua La Grande has 91% of its area under a flood hazard classification of severe to extreme flooding risk, which was expected given its location downstream of the reservoir. Similarly, the town of Sitiecito, has 63% of its area classified as extreme risk for flooding. In the case of the town of Isabela de Sagua, since it is located on the coast, the hazard classification ranges from moderate to significant risk. Other populated areas classified as caution and moderate risk for flooding include La Rosita, Playa Uvero, Dos Amigos, and Playa Piñón. Even the town Caharatas, located far from the dam breach, could be affected by the rising water level and humidity of the surrounding soil.

4. Discussion

In this study, the methodology applied in Ferrari, Vacondio and Mignosa [

29] was adapted to the local conditions and data limitations of this particular study area in Cuba, starting with hydrological and hydraulic analyses until obtaining the dam failure hazard map similar to those developed by Paşa, Peker, Hacı and Gülbaz [

37]. Using the hazard model reported by NSW and DPIE [

31], the flood hazard in the area was analyzed and mapped for better understanding of the extent of the affected areas. The depth and velocity values produced by the simulations (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) can lead to significant riverbed erosion and landslides. Therefore, the river geometry can change during the flood event as reported in [

20,

29,

32,

39]. Furthermore, mud and debris carried by the current can affect the dynamic conditions of the flow, which turns the water into a non-Newtonian fluid [

3]. However, the results obtained do not take this into consideration; models with greater capacity and improvements in the implementation of roughness coefficients and/or non-Newtonian models are needed for future work.

Simulation results reported that dam failure affects traffic roads and nearby populated areas such as the city of Sagua La Grande and nearby towns and communities such as Carahatas and Uvero and Isabela beaches in Sagua. Based on the use of rupture models, the most catastrophic event was determined to be the sudden failure of 350 m in 0.67 h (Scenario 13). Although the scenarios related to a piping type dam failure were the least dangerous, simulated flows up to 8,000 m

3/s could produce an overtopping of the protective dike at the entrance to the city of Sagua La Grande (See Figure SI4). The results are consistent with the events recorded by USACE [

3]; Fattorelli and Fernández [

1] and Aureli, Maranzoni and Petaccia [

6], which suggested that piping events are less dangerous compared to overtopping dam failure. For the study area, flood depth, flow, and flow velocity were determined to be as high as 12.47 m, 35,727 m

3/s, and 5.55 m/s, respectively, at the Sagua La Grande Highway Bridge (CP1) cross-section. Furthermore, results showed that flooding could reach a maximum flow of 35,727 m

3/s in 1.13 hours at the same cross-section of the El Triunfo Bridge in the city of Sagua La Grande.

Comparing these results in

Table 6 with simulations performed on dams with similar characteristics, it was observed that for dams of similar size and volume, the results of scenarios 1-12 are consistent with other studies [

1,

2,

3]. An example is the Oros Dam in Brazil, with a height of 35.4 m and 700 Mm

3, which produced a discharge flow close to 10,000 m

3/s. However, Scenario 13 exceeds the values recorded in similar episodes, which is significant since other dams smaller than the Alacranes Dam also increase their peak discharge, mainly influenced by the volume and height as it may occur with the Malpasset Dam in France. These differences can be attributed to several factors including the dam height, crest length, the volume of water stored, data quality, and model accuracy. Furthermore, geographic conditions such as slope, land cover, etc. are other factors that may lead to varying flood depth and velocity as the reported values in studies presented in

Table 6.

It is important to consider that simulations are based on hydrological models that, although accurate, cannot predict all variables of water behavior in a real-life scenario [

40]. Factors such as soil erosion and climate variability, as well as the presence of atmospheric events, can influence the results. Therefore, follow-up studies are recommended to validate and adjust the model to combinations with intense rainfall, drought, or other initial boundary conditions, including breach parameters.

The use of web-based mapping tools such as DWR and SDSOD [

45] to map reservoir breach flooding and flooding hazards in different locations across the state of California is an example of how scientific research can be integrated with state agencies responsible for public safety. Furthermore, future research could explore the effectiveness of different mitigation strategies in specific areas, which would contribute to more informed and effective urban planning. The flood velocity and hazard maps developed in this study indicated exposed areas with high population density. By delimiting these areas and the number of inhabitants affected by the potential of the Alacranes Dam failure this would allow for establishing a relationship between the total flooded area and peak break runoff. While this is an empirical equation and is only valid for use in the study area with limitations, it is a first approximation of a regional study in the province of Villa Clara, Cuba. It is believed that the methodology presented in this research can be replicated in other areas, as a useful tool for preliminary risk assessment for flooding events. This could provide insights and useful information for further implementing a warning system for emergency and evacuation plans for communities living in flood-prone areas.

5. Conclusions

The results of hazard maps for the Alacranes Dam failure scenarios provided valuable information for risk assessment and urban planning by identifying areas effected by potential flooding from dam breaching events. This could provide useful information to develop strategies to minimize the risks associated with dam failure. The simulation of multiple failure scenarios using different mathematical models showed significant variations in parameters such as flooded area, maximum depth and maximum flow velocity, which depended of the type of structural failure of the dam. According to the HEC-RAS physical model, the most critical failure scenario was Scenario 13, with the formation of a 350 m breach in just 0.67 h. The depth, velocity, and maximum discharge could be a significant hazard, endangering important infrastructure and several populated areas downstream of the dam.

For the first time, depth, velocity, and flood hazard maps were generated for the affected areas downstream of the Alacranes Dam in Cuba, allowing the identification of populated areas potentially affected by a potential failure event. Further improvements in methodologies are needed, as well as more detailed studies on the impact of potential dam failures, considering factors such as process dynamics, interaction with channel geometry, and real-time data. These types of studies are useful for emergency planning by identifying exposed areas and potential impacts to minimize the risks associated with dam failures.

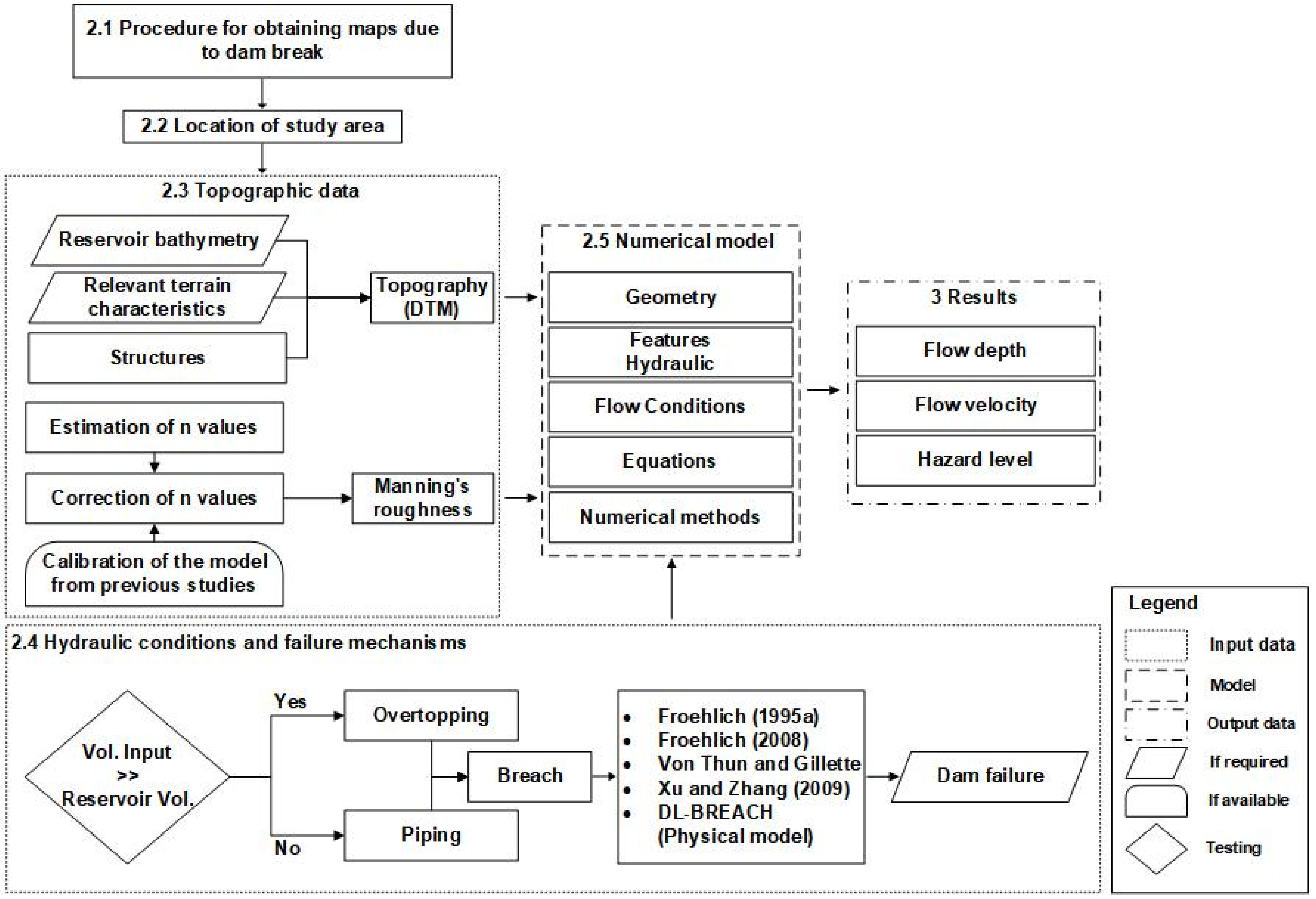

Figure 1.

Flowchart for obtaining depth, speed and hazard maps for the Alacranes Dam.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for obtaining depth, speed and hazard maps for the Alacranes Dam.

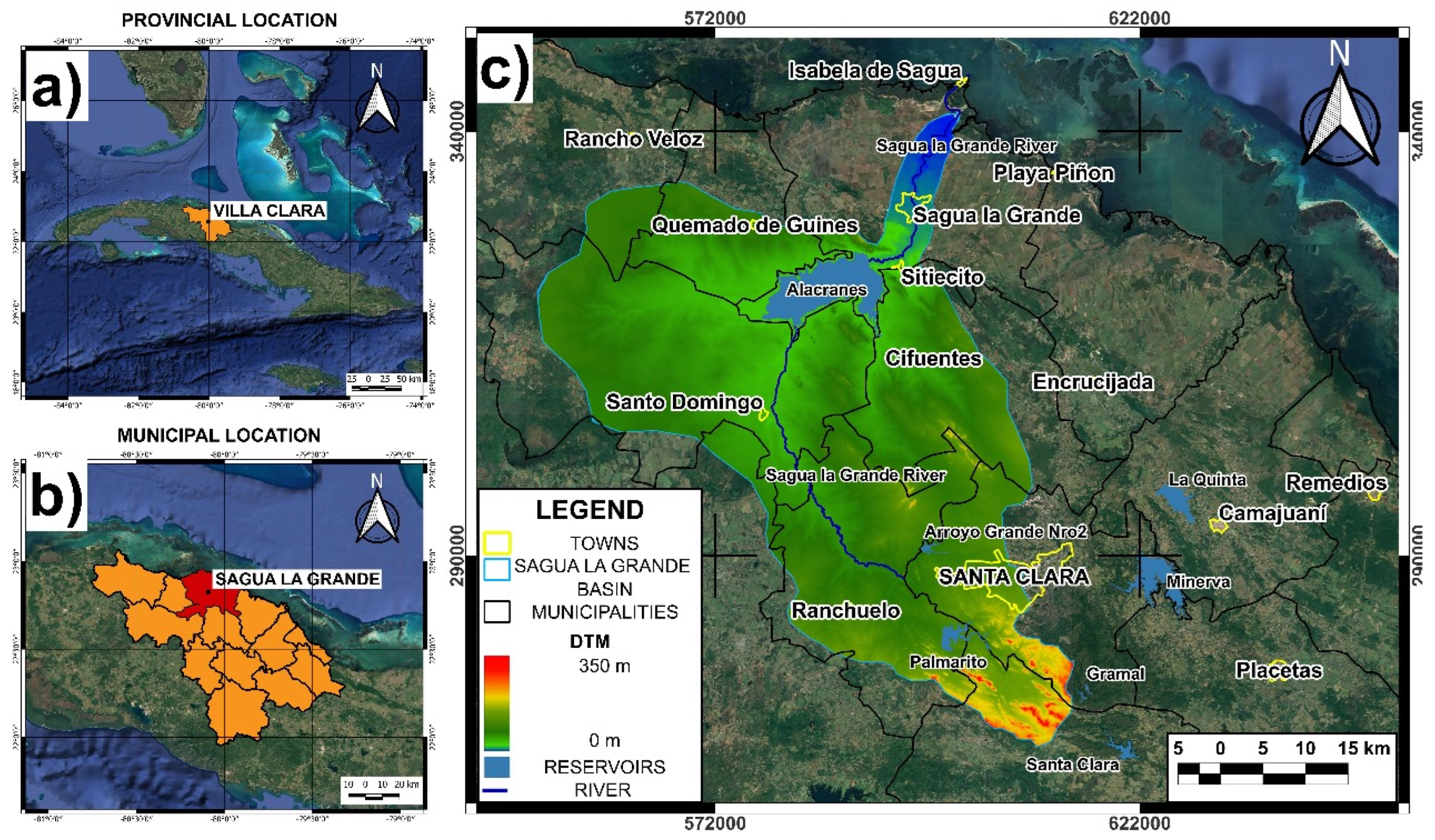

Figure 2.

(a) Location of the island of Cuba, with the Villa Clara region represented in orange, (b) zoom of Villa Clara with the division by cities (the city of Sagua La Grande highlighted), (c) the represent the DTM around the Alacranes Dam in the extension of the Sagua La Grande basin and nearby towns and other reservoirs.

Figure 2.

(a) Location of the island of Cuba, with the Villa Clara region represented in orange, (b) zoom of Villa Clara with the division by cities (the city of Sagua La Grande highlighted), (c) the represent the DTM around the Alacranes Dam in the extension of the Sagua La Grande basin and nearby towns and other reservoirs.

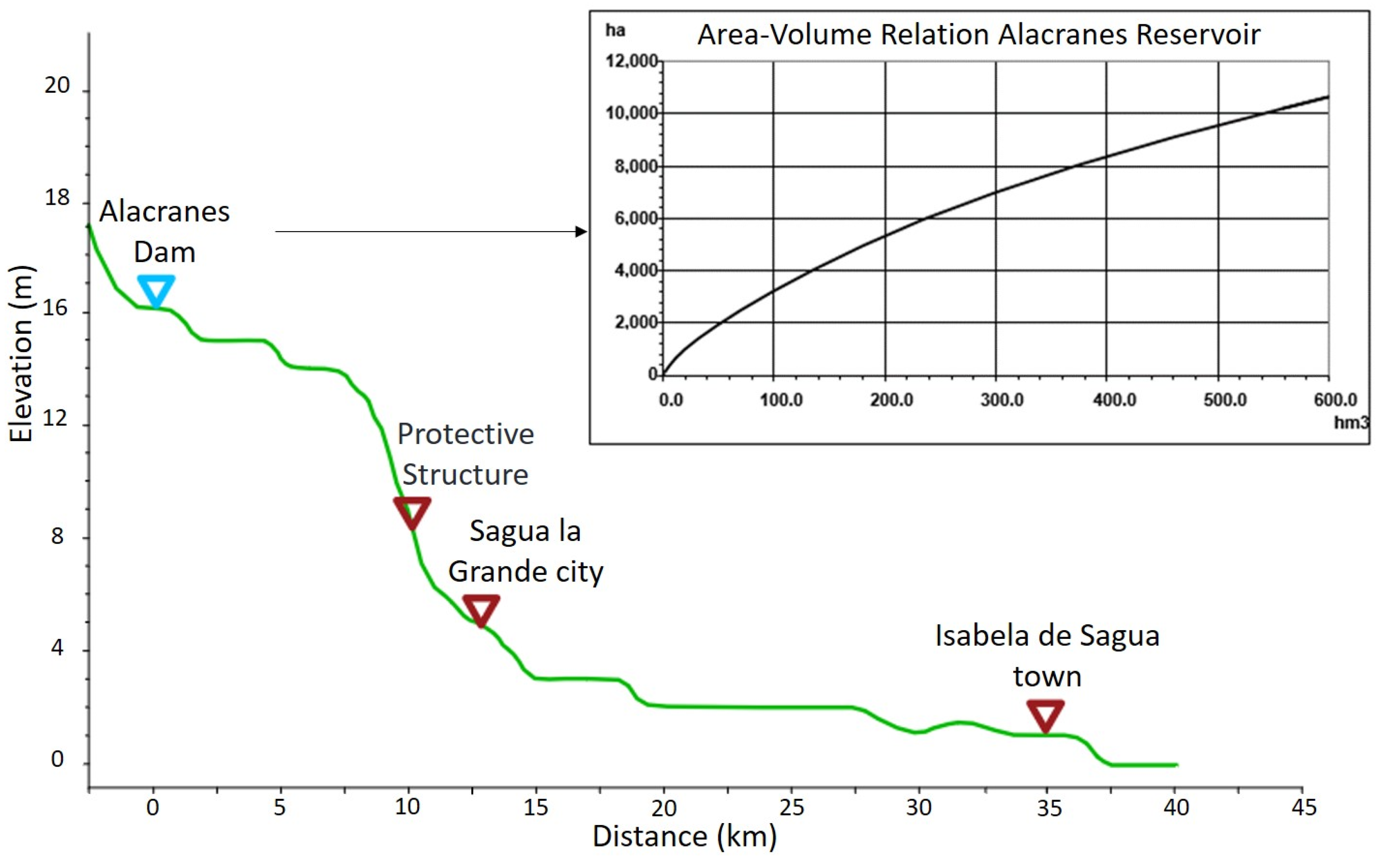

Figure 3.

Longitudinal topographic profile and locations of points of interest from the Alacranes Reservoir to the mouth of the Sagua River in the town of Isabela de Sagua. The reservoir's area-volume curve is shown on the right.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal topographic profile and locations of points of interest from the Alacranes Reservoir to the mouth of the Sagua River in the town of Isabela de Sagua. The reservoir's area-volume curve is shown on the right.

Figure 4.

DTM Modified digital elevation model of the Sagua La Grande basin highlighting the names of nearby towns.

Figure 4.

DTM Modified digital elevation model of the Sagua La Grande basin highlighting the names of nearby towns.

Figure 5.

Representation of (a) Water footprint (b), estimated Manning´s coefficient, (c) modeled flood and (d) modified Manning´s coefficient. The different control points (CP) are represented in red circles.

Figure 5.

Representation of (a) Water footprint (b), estimated Manning´s coefficient, (c) modeled flood and (d) modified Manning´s coefficient. The different control points (CP) are represented in red circles.

Figure 7.

Map of simulated velocities at the time of greatest flood intensity obtained in Scenario 13. To the right is the city of Sagua la Grande, with CP 2 marked in the center.

Figure 7.

Map of simulated velocities at the time of greatest flood intensity obtained in Scenario 13. To the right is the city of Sagua la Grande, with CP 2 marked in the center.

Figure 8.

The Alacranes reservoir hazard map for Scenario 13 reservoir failure. To the right is the city of Sagua la Grande, with CP 2 marked in the center.

Figure 8.

The Alacranes reservoir hazard map for Scenario 13 reservoir failure. To the right is the city of Sagua la Grande, with CP 2 marked in the center.

Table 1.

Variation of depth and speed under a sensitivity analysis for Manning´s coefficients.

Table 1.

Variation of depth and speed under a sensitivity analysis for Manning´s coefficients.

| Point Name |

Modified Mannig´s Coefficent |

0 Variation Manning´s coefficent |

-20% Variation Manning´s coefficent |

+20% Variation Manning´s coefficent |

| Depth (m) |

Velocity (m/s) |

Depth (m) |

Velocity (m/s) |

Depth (m) |

Velocity (m/s) |

| CP1 |

0.074 |

8.41 |

1.35 |

7.95 |

1.57 |

8.82 |

1.21 |

| CP2 |

0.091 |

9.37 |

2.28 |

9.15 |

2.76 |

9.55 |

1.99 |

| CP3 |

0.029 |

0.20 |

0.21 |

0.17 |

0.22 |

0.23 |

0.2 |

| CP4 |

0.056 |

0.52 |

0.36 |

0.45 |

0.41 |

0.57 |

0.31 |

| CP5 |

0.029 |

0.69 |

1.04 |

0.51 |

1.05 |

0.85 |

1.00 |

| CP6 |

0.029 |

0.24 |

0.39 |

0.20 |

0.43 |

0.27 |

0.36 |

Table 2.

Modeling scenarios for the Alacranes Dam failure.

Table 2.

Modeling scenarios for the Alacranes Dam failure.

| Scenarios |

Formulation |

Type of Dam failure |

| Scenario 1 |

Froehlich David [9] |

Overtopping |

| Scenario 2 |

Froehlich David [11] |

| Scenario 3 |

Von Thun y Gillette (1990) A* |

| Scenario 4 |

Von Thun y Gillette (1990) B* |

| Scenario 5 |

Von Thun y Gillette (1990) C* |

| Scenario 6 |

Xu and Zhang [12] |

| Scenario 7 |

Froehlich David [9] |

Piping |

| Scenario 8 |

Froehlich David [11] |

| Scenario 9 |

Von Thun y Gillette (1990) A* |

| Scenario 10 |

Von Thun y Gillette (1990) B* |

| Scenario 11 |

Von Thun y Gillette (1990) C* |

| Scenario 12 |

Xu and Zhang [12] |

| Scenario 13 |

Modelo Físico de HEC RAS [30] |

Overtopping |

| *According to USACE [3] the Von Thun and Gillette breach formation time equations are presented for both erosion-resistant and easily erodible dams, the original publication of both authors suggests that these limits be considered as upper limit and lower limit (A and C, respectively), while B is an intermediate value of erosion resistance. |

Table 3.

Key parameters extracted from the modeling of the breakage scenarios.

Table 3.

Key parameters extracted from the modeling of the breakage scenarios.

| Scenarios |

Dam failures |

TFA (km2) |

MWD (CP1) (m) |

MWV (CP1) (m/s) |

FAT (CP2) (h) |

RET (h) |

TTF (h) |

AWV (CP2) (m/s) |

| Scenario 1 |

Overtopping |

595.7 |

10.76 |

3.46 |

1.67 |

40.00 |

26.66 |

2.57 |

| Scenario 2 |

594.1 |

10.80 |

3.42 |

1.67 |

34.00 |

29.00 |

2.50 |

| Scenario 3 |

562.1 |

9.73 |

3.60 |

1.58 |

49.50 |

64.75 |

2.63 |

| Scenario 4 |

561.5 |

9.68 |

3.38 |

1.67 |

49.50 |

64.00 |

2.94 |

| Scenario 5 |

567.9 |

9.79 |

3.60 |

1.33 |

52.00 |

38.00 |

3.07 |

| Scenario 6 |

585.1 |

10.16 |

3.32 |

1.83 |

46.00 |

29.34 |

2.60 |

| Scenario 7 |

Piping |

556.6 |

9.57 |

3.22 |

3.00 |

36.00 |

23.67 |

2.29 |

| Scenario 8 |

548.8 |

9.35 |

3.22 |

3.00 |

34.00 |

25.00 |

2.32 |

| Scenario 9 |

501.7 |

8.48 |

3.31 |

2.67 |

49.50 |

34.66 |

2.74 |

| Scenario 10 |

510.8 |

8.58 |

3.35 |

2.21 |

45.25 |

32.37 |

2.65 |

| Scenario 11 |

519.9 |

8.69 |

3.40 |

1.75 |

41.00 |

30.08 |

2.56 |

| Scenario 12 |

530.7 |

8.81 |

3.19 |

3.33 |

45.00 |

30.34 |

2.53 |

| Scenario 13 |

Overtopping |

604.6 |

12.47 |

5.55 |

1.33 |

43.67 |

23.34 |

3.21 |

Table 4.

Computational, mathematical and hydraulic parameters of the breach formation at the Alacranes Dam outlet.

Table 4.

Computational, mathematical and hydraulic parameters of the breach formation at the Alacranes Dam outlet.

| Scenarios |

Dam failures |

Breach bottom width (m) |

Breach development time (h) |

Running time |

Overall volume accounting error |

Qmax

(m3/s) |

Courant |

| h |

min |

s |

1000 m3

|

% |

|

Max |

Min |

| Scenario 1 |

Overtopping |

345.0 |

11.88 |

32 |

26 |

2 |

21,303.0 |

2.352 |

19,505 |

1 |

0.45 |

| Scenario 2 |

311.0 |

10.34 |

19 |

3 |

8 |

94.44 |

0.011 |

19,893 |

| Scenario 3 |

100.4 |

0.50 |

26 |

32 |

12 |

71.60 |

0.008 |

13,480 |

| Scenario 4 |

100.4 |

1.00 |

27 |

13 |

14 |

76.85 |

0.009 |

12,983 |

| Scenario 5 |

95.0 |

0.65 |

13 |

14 |

9 |

34.07 |

0.004 |

15,184 |

| Scenario 6 |

207.0 |

11.71 |

31 |

51 |

59 |

89.96 |

0.010 |

15,553 |

| Scenario 7 |

Piping |

171.0 |

6.69 |

23 |

50 |

14 |

93.14 |

0.020 |

12,423 |

| Scenario 8 |

166.0 |

6.02 |

15 |

17 |

37 |

85.00 |

0.018 |

11,291 |

| Scenario 9 |

90.0 |

0.40 |

19 |

55 |

27 |

55.38 |

0.012 |

6,860 |

| Scenario 10 |

90.0 |

1.20 |

20 |

15 |

7 |

50.58 |

0.011 |

7,064 |

| Scenario 11 |

85.0 |

0.57 |

18 |

58 |

40 |

59.86 |

0.013 |

8,122 |

| Scenario 12 |

109.0 |

9.70 |

26 |

46 |

36 |

66.49 |

0.014 |

8,297 |

| Scenario 13 |

Overtopping |

350.0 |

0.67 |

31 |

29 |

40 |

22,928.0 |

2.531 |

35,726 |

Table 5.

Surface classification (in percentage) according to the level of flood hazard for the main populated areas affected by the reservoir failure.

Table 5.

Surface classification (in percentage) according to the level of flood hazard for the main populated areas affected by the reservoir failure.

| |

Flood Risk Ratings |

| City or locality |

Low |

Caution |

Moderate |

Significant |

Severe |

Extreme |

| Sagua La Grande |

1 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

61 |

30 |

| Sitiecito |

3 |

2 |

6 |

9 |

16 |

63 |

| Isabela de Sagua |

11 |

16 |

49 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

| La Rosita1

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

50 |

| Nueva Isabela |

26 |

32 |

40 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

| Dos Amigos |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

| Playa Uvero |

0 |

0 |

0 |

64 |

36 |

0 |

| Playa Piñon |

0 |

0 |

0 |

81 |

19 |

0 |

| Caharatas2

|

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Total affected area |

9 |

10 |

27 |

18 |

30 |

6 |

1The town of La Rosita is located near areas of extreme risk for flooding, therefore the surface of this town was classified as 50% Severe, 50% Extreme risk of flooding.

2The town of Caharatas is not located directly within the flood hazard area, due to its proximity to the affected area, this town was classified as 100% Low risk for flooding. |

Table 6.

Comparisons between this study and other studies of dam failure using HEC-RAS 2D model.

Table 6.

Comparisons between this study and other studies of dam failure using HEC-RAS 2D model.

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

| Alacranes |

Cuba |

21 |

350 |

O |

350 |

604.6 |

10.8 |

3.5 |

35,726 |

This study |

| Ain Kouachia |

Marruecos |

22 |

11 |

O |

88 |

3.2 |

20.3 |

8.0 |

9,238 |

[20] |

| Yabous |

Argelia |

43 |

8 |

O |

26 |

23.9 |

14.1 |

38.6 |

8,767 |

[41] |

| Kibimba |

Uganda |

4.5 |

15 |

O |

43 |

N/A |

6.0 |

10.0 |

1,935 |

[35] |

| Xe Namnoy |

Laos |

34 |

1050 |

O |

N/A |

46,0 |

9.5 |

12,0 |

8,500 |

[39] |

| Chengbi River |

China |

70 |

1121 |

O |

125 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

33,5693 |

[32] |

| Wadi Al-Arab |

Jordania |

84 |

20 |

O |

102 |

N/A |

37.6 |

8.9 |

10,800 |

[42] |

| Wala |

Jordania |

54 |

25 |

O |

133 |

N/A |

43.0 |

17.1 |

12 |

[43] |

| Grand Ethiopian Renaissance (GERD) |

Etiopía |

145 |

74000 |

O |

200 |

N/A |

50.0 |

7,0 |

325 |

[44] |

1: Reservoir name, 2: Country, 3: Dam height (m), 4: Dam volume (Mm3), 5: Overtopping (O: Overtopping), 6: Breach width (m)

7: Total flooding area (km2), 8: Maximum water depth (m), 9: Maximum water velocity (m/s), 10: Peak discharge (m3/s), 11: References N/A: Not available |