1. Introduction

Pneumococcal disease is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among the elderly and individuals with specific underlying diseases [

1].

The introduction of multivalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) has decreased the burden of pneumococcal disease [

2], and carriage of pneumococcal serotypes targeted by PCVs [

3] in the overall population.

PCV effectiveness in preventing pneumococcal disease in children has been documented, initially for 7-valent PCV [

4] and then for higher valency vaccines such as 10-valent PCV [

5] and 13-valent PCV [

6,

7]. Vaccination programs for children have also led to indirect protection of older adults via herd immunity, but based on the considerable and persisting burden of disease in the elderly, there has been a push towards targeted vaccination in this age group.

In Italy, despite the implementation of pneumococcal vaccination in Italian newborns starting from the beginning of the twentieth century, IPD remain the most common type of invasive bacterial disease [

8] with regional disparities highlighting the need for enhanced public health interventions [

9]. The Italian National Immunization Programme (NIP) 2012-2014 [

10] recommended pneumococcal vaccination to individuals at higher risk independently by the age and the following NIP 2017-2019 [

11] extended the recommendations to the elderly population advising to vaccinate them with PCV13 followed by 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). The latter has been available for many years before the approval of PCV7 and widely used to provide protection in adults and high-risk populations. PPSV23 targets a broader spectrum of pneumococcal strains but does not induce a strong immune memory response as the conjugate vaccines do and is not able to elicit a protective immune response in children under the 2 years of age. PPSV23 has been an important tool for the prevention of pneumococcal diseases in individuals at higher risk and was proven effective in preventing IPD and community-acquired pneumonia, particularly [

12].

More recently, in 2022, the 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV15) has been approved in Italy for adults first [

13] and for pediatric use later [

14]. PCV15 includes two additional serotypes (22F and 33F) compared to PCV13, and shows a stronger response to serotype 3 which remains one of the leading causes of IPD in older adults [

15]. Another conjugate vaccine, the 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20), was approved for adults in 2021 [

16] and for children in 2023 [

17]. It includes additional serotypes not covered by PCV13 and PCV15 offering enhanced and more comprehensive coverage.

Based on the new available PCVs, the CDC [

18] recommends administering PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21—the last PCV become available that covers eight serotypes not included in any of the other currently available vaccines [

19] to all adults 50 years or older who have never received any PCV or with an unknown vaccination history. The recommendations also foresee administering a following dose of PPSV23, if PCV15 is used.

The last and current Italian NIP 2023-2025 [

20] does not provide indications about the use of different available vaccines for the elderly vaccination. Nevertheless, for practical reasons and to simplify vaccination management, many regions in Italy have started implementing protocols favoring the use of PCV20.

For an appropriate deployment of elderly pneumococcal vaccination, data on coverage are needed to both better understand which strategies can be implemented and monitor the vaccination campaign. Nevertheless, comprehensive and updated information on pneumococcal vaccination coverage is available for the pediatric population only, with national data showing a coverage rate of 91.73% and 94.38% in 2022 and 2023 respectively [

21]. In contrast, knowledge about adult at risk and elderly vaccination coverage remains limited. In the Emilia-Romagna region, the coverage with at least one dose of a PCV among cohorts born between 1952 and 1958 is reported to be 36.1% [

22]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no data are available regarding the adherence to the sequential pneumococcal vaccination.

Starting in 2018, the Lazio region implemented the sequential pneumococcal vaccination to offer elderly with broader protection against pneumococcal diseases. With this research we aim to monitor the vaccination strategy launched in 2018 by evaluating the coverage of sequential pneumococcal vaccination among individuals turning 65 years old in the Local Health Authority (LHA) of Viterbo, a province of Lazio Region, Italy.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Setting

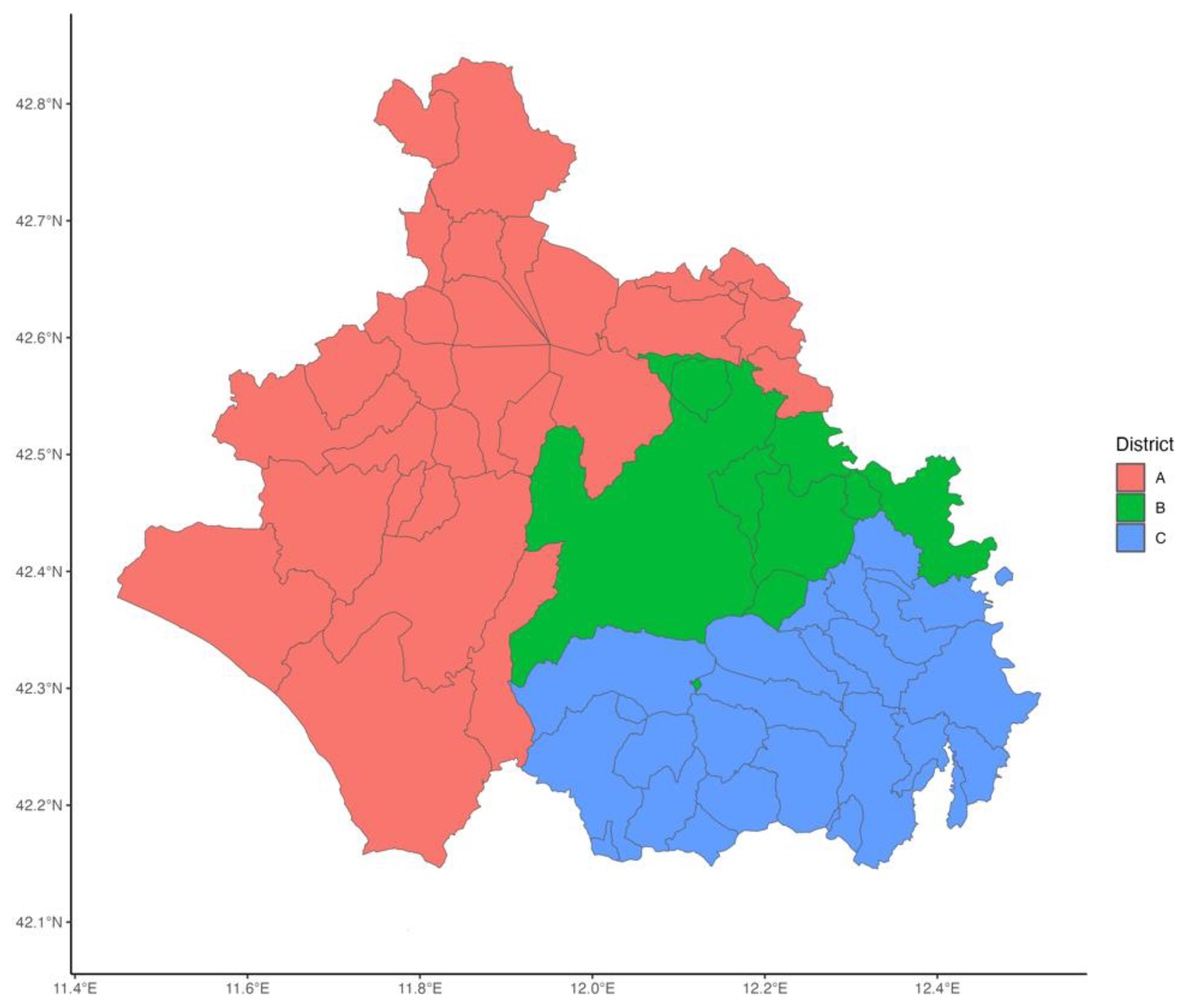

The study was conducted within Viterbo LHA, which encompasses the city of Viterbo and 59 municipalities within Viterbo province. The LHA is administratively divided into three districts: A, B, and C, representing distinct territorial subdivisions for healthcare service delivery. These districts are illustrated in

Figure 1. The LHA features vaccination centers specifically dedicated to adult immunization. District A hosts two vaccination centers, while Districts B and C have one vaccination center each one. The delivery of vaccination services is organized consistently across all districts with both GPs and vaccination centers providing vaccination.

Study Design and Data Sources

This study is a retrospective observational cohort study considering all individuals residing in the LHA of Viterbo, Lazio Region, Italy, who turned 65 years of age between 2018 and 2023.

For the construction of the dataset, data on individuals belonging to the birth cohorts of interest (1952–1958) were first extracted from the Regional Vaccination Registry (AVR), a digital platform for managing and recording vaccinations in the Lazio region. This initial dataset included the list of individuals along with summary information on the uptake of pneumococcal vaccination with number of doses, but without information on the specific vaccine types that were administered. To clarify whether individuals who had received at least two doses did the sequential pneumococcal vaccination a second internal dataset was retrieved, containing details of pneumococcal vaccine types administered from 2018 to 2024 in the LHA of Viterbo, including the vaccination dates and the associated individuals. These two datasets were merged using a unique individual code as the key. All data were processed exclusively by LHA personnel, as data controllers, through procedures ensuring the confidentiality and security of the information, in compliance with EU Regulation 2016/679 (GDPR) and national legislation, based on consent obtained at the time of vaccination.

Variables Considered

The outcome variable—adherence to the sequential pneumococcal vaccination—was determined by evaluating these conditions:

The presence of at least two doses of pneumococcal vaccines registered in the AVR.

The registration of both PCV13 and PPSV23 in the internal database, with the latter administered after the PCV.

A time interval between individual’s 65th birthday and the administration date of the PPSV23 vaccine less than two years.

The independent variables included sex, citizenship, district of residence, and municipality size, determined by linking ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) population data to everyone’s place of residence.

Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis of the coverage in respect to the sequential pneumococcal vaccination was performed across cohorts of individuals turning 65 years old each year. Coverages were reported in percentages.

Additionally, a univariable analysis through Chi square test and a logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the factors associated with the outcome variable. Independent variables included sex, citizenship, municipality size, and district of residence, and the results were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals.

The significance level was set at 0.05 and statistical analysis were performed using RStudio (version 4.3.3).

Geomapping and Geocoding

Vaccination coverages were also geocoded using address information recorded in AVR. A geographic database with county and regional boundaries in vector format (SHP file) was obtained from Open Data Lazio Region (

https://dati.lazio.it/home). RStudio (version 4.3.3) was used for spatial analysis.

3. Results

The characteristics of individuals turning 65 years old across the whole study period and their vaccination coverage are summarized in

Table 1. This cohort included a total of 27,657 individuals, of whom 640 completed the sequential pneumococcal vaccination, resulting in an overall coverage of 2.32%. Significant differences in vaccination coverage were identified in respect to all the independent variables considered. Females demonstrated a higher coverage (2.58%) compared to males (2.04%) (p = 0.003). Coverage also varied by citizenship, with Italian citizens exhibiting a higher coverage (2.45%) compared to foreign residents (0.64%). Across health districts, differences were observed, with District C showing the highest coverage (3.03%), followed by District B (2.76%) and District A (1.08%). Furthermore, the size of the municipality of residence was associated with significant differences, as individuals residing in municipalities with 10,000 or fewer inhabitants showed higher coverage (2.52%) compared to those in municipalities with more than 10,000 inhabitants (1.98%).

These differences resulted in an increased OR for the sequential pneumococcal vaccination in females compared to males (OR: 1.324, 95% CI: 1.13–1.553, p < 0.001), residents in municipalities with 10,000 or fewer inhabitants compared to those in larger municipalities (OR: 1.482, 95% CI: 1.233–1.786, p < 0.001) and residents in Districts B and C as compared to those in District A (OR: 3.074, 95% CI: 2.4–3.963, and OR: 2.822, 95% CI: 2.255–3.563, respectively, both p < 0.001) (

Table 2). On the contrary foreign citizens had substantially lower odds of completing the sequential pneumococcal vaccination compared to Italian citizens (OR: 0.245, 95% CI: 0.134–0.407, p < 0.001).

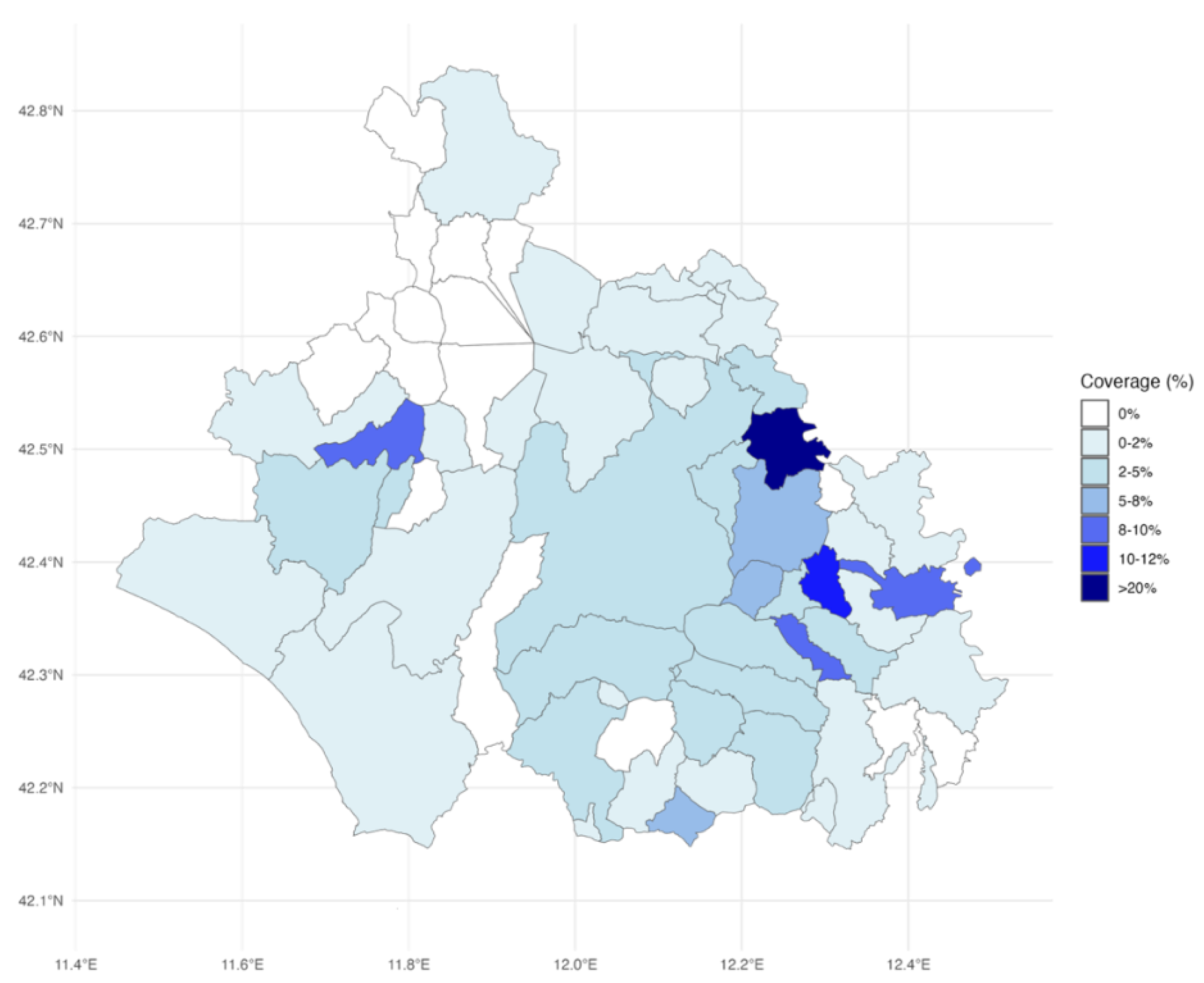

The spatial analysis highlights geographic disparities in vaccination coverage across the Viterbo LHA (

Figure 2). Areas with the highest vaccination coverage were concentrated in specific municipalities in the eastern and southeastern regions, corresponding largely to District C, as indicated by the darker shades on the map. These municipalities were also characterized by smaller populations. In contrast, the northern region, which encompasses District A, exhibited lower coverage, with 10 municipalities recording zero newly 65-year-old residents who completed the sequential pneumococcal vaccination during the study period.

Vaccination coverage among the newly 65-year-old residents in Viterbo LHA remained low from 2018 to 2023, with significant variability across years and subgroups (

Table 3). In particular, coverage increased from 0.60% in 2018 to a peak of 3.27% in 2020, reflecting initial improvements in adherence to the vaccination campaign. However, this was followed by a plateau in 2021–2022 and a decline to 2.53% in 2023.

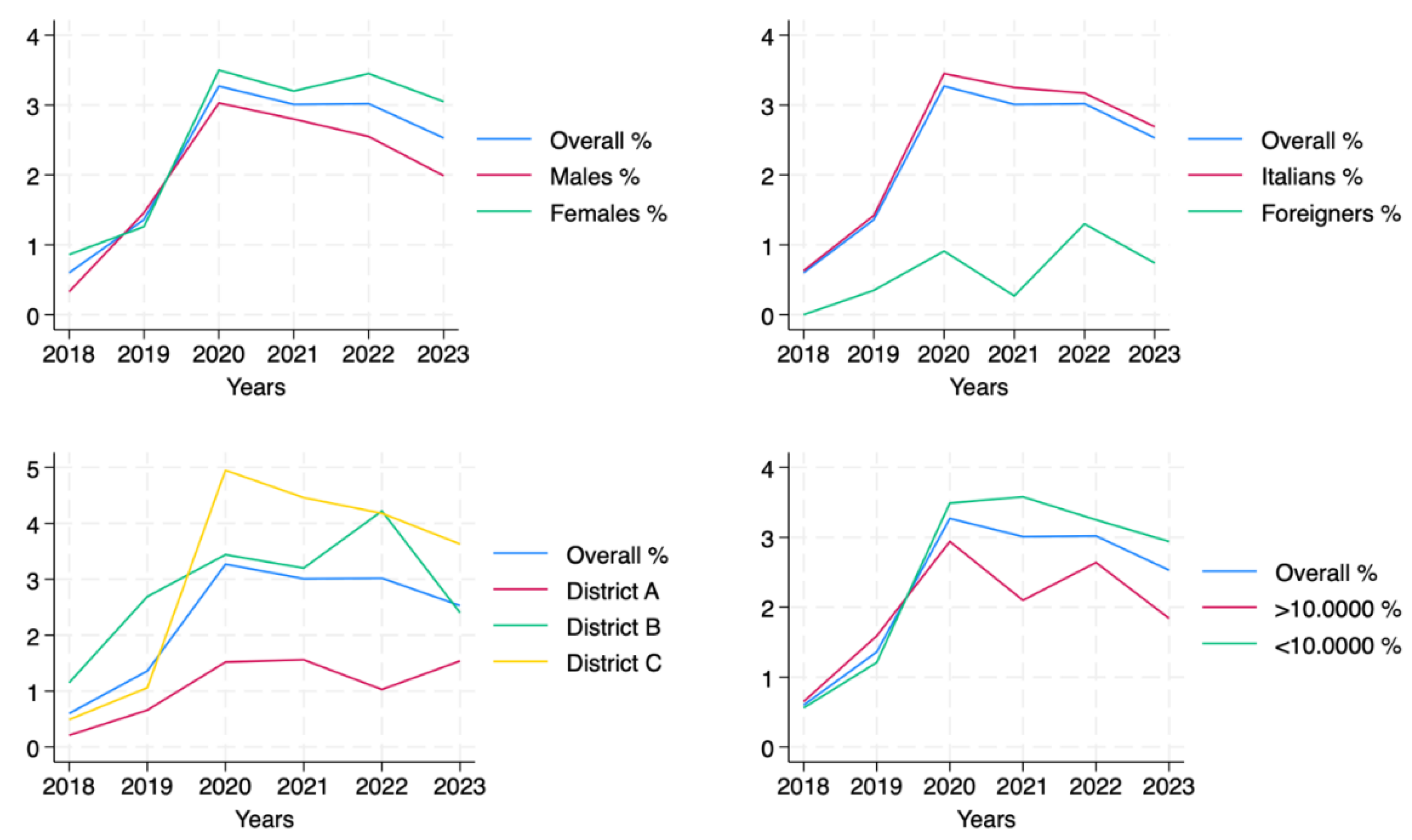

As illustrated in

Figure 3, vaccination coverage trends among the newly 65-year-old residents showed variability across demographic and geographic subgroups. Females showed higher coverage than males, with a rise in the first years and a moderate decline after 2020. Italian citizens followed a similar trend, maintaining higher coverage than foreign residents. Geographic analysis revealed that District C led in coverage, peaking at 4.72% in 2020, while District A had the lowest values, never exceeding 1.53%. Interestingly, District B showed sustained growth, reaching 4.05% in 2022, before a slight decrease in 2023. Coverage was also higher in smaller municipalities (≤100,000 inhabitants), where the trend mirrored the overall population with a marked rise in 2020, followed by a stabilization and subsequent decline.

4. Discussion

This retrospective observational cohort study examined the coverage of the sequential pneumococcal vaccination (PCV13 followed by PPSV23) among newly 65-year-old residents in Viterbo LHA between 2018, which was the year of the launch of the sequential vaccination strategy in the Lazio region, and 2023. The overall coverage across the whole study period was very low, with improvements between 2018 and 2020 followed by a plateau and a decline.

Differences between demographic and geographical subgroups were also found. In particular females, Italian citizens and residents of smaller municipalities showed higher coverages. In geographical terms, there was significant variability in coverage, with Districts B and C showing higher coverage than District A, which also had municipalities without any elderly with the sequential vaccination completed.

The observed decline seen after the peak in 2020 can be attributed to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted health care services and vaccination campaigns worldwide. Nevertheless, after the pandemic, the introduction of PCV20 might also have contributed to the decline, as it has gradually replaced the sequential pneumococcal vaccination for newly 65-year-olds in Italy. Nevertheless, this effect concerns 2023 and, in Lazio region, applies only to those not previously vaccinated because those already vaccinated with PCV13 continue with the sequential schedule, without serotype catch-up using PCV20.

The low coverage found in our study is in line with the 4% uptake of the pneumococcal sequential vaccination in a German study [

23] that investigated a high-priority group. While our study included people only based on age, without collecting data on underlying health conditions, both our study and the German one illustrate the difficulty of achieving appropriate coverage, even in high-priority groups.

Information and education are two pillars in making it possible to increase vaccination coverage. The evidence [

24,

25] already provides clear proofs of the effectiveness of the sequential pneumococcal vaccination. In respect to safety also, a study conducted in Puglia [

26] reported serious adverse events after PCV13 and PPSV23 in less than 0.1‰ of doses administered, with the vast majority being mild and self-limiting. Health professionals entrusted to deliver pneumococcal vaccination in the elderly, mostly represented in Italy by General practitioners (GPs), should take advantage of their relationship with the patients to provide them with accurate and reliable information about both the efficacy and safety of the sequential pneumococcal vaccination. This is a fundamental step to encourage patients’ adherence to vaccination.

The observed limited vaccination coverage is concerning also considering that a recent cost-effectiveness analysis conducted in Italy [

27] supports to pursue the sequential strategy independently by the PCV used because PPSV23 is affordable and increase health outcomes. If this is going to happen, it is necessary to develop and put in place interventions to increase the uptake of the second dose to protect people from pneumococcal diseases.

Strengths exist within this work. it gives a thorough assessment of the sequential pneumococcal vaccination coverage among newly turned 65-year-olds in a six-year time frame, revealing trends in vaccination and disparities in a natural setting. The findings of the study can be useful to inform public health interventions also based on differences shown across subgroups. Furthermore, the use of the regional vaccination registry as source of data enhances the validity and reliability of the results.

However, there are also some limitations. The study did not collect data on potential health-related conditions that could impact the uptake of vaccination, thus preventing the analysis of coverage among high-risk subgroups. Additionally, the analysis considered people who completed the sequential vaccination within 2 years from their 65th birthday. Nevertheless, there may have been individuals who completed the sequential vaccination after this time window. Similarly, as the study considered only the resident population in Viterbo LHA it could not be excluded that someone completed the vaccination outside the Lazio region. Individual reasons for being not vaccinated were not evaluated, leaving some gaps in understanding potential barriers to pneumococcal vaccination. Another relevant aspect that emerged was the gap in completeness of data in the AVR, which was overcome by consulting another internal database. This can limit the transferability of our approach to other contexts. Finally, our findings, in particular those regarding the geographical disparities, cannot be considered generalizable because they are strictly related to Viterbo LHA organizational context. In fact, despite the districts share the same organization of the vaccination delivery, differences that were observed could be explained by GP participation in the campaign and logistical access issues.

These limitations suggest the need for additional research to create a more holistic understanding of pneumococcal vaccination uptake.5.

5. Conclusions

The present study highlighted that the coverage of the sequential pneumococcal vaccination has remained very low after the launch of the strategy. Furthermore, significant differences emerged in respect to individual and geographical characteristics. This underscores a significant gap between recommendations and their actual implementation.

Monitoring vaccination coverage and assessing also inequalities allows for the implementation of public health strategies to address potential criticisms. The introduction of electronic vaccination registries has clearly elevated the capacity to monitor coverage with secure and timely access to data. Nevertheless, resources and methods should be implemented to routinely do it. Furthermore, the assessment of coverage cannot be complete, though, without the addition of other important information, like patients’ health status or medical indications/contraindications for vaccination. While these data are typically requested when a patient is registered for the vaccine, they are often not complete, meaning they remain mostly unusable.

Improving the completeness and accuracy of data would enable health authorities to better understand how the vaccination strategy is deployed and adjust their approaches to suit various population groups’ needs, ultimately enhancing the success of vaccination campaigns.

Author Contributions

For Conceptualization A.B., C.D.W; methodology, A.B., C.D.W.; formal analysis, A.B., C.D.W; data curation, A.B; writing—original draft preparation, A.B., C.D.W, F.C., F.V., G.S., S.A.; writing—review and editing, A.B., C.D.W, F.C., F.V., G.S., S.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed Consent Statement

All vaccination data used in this study were obtained from the Regional Vaccination Registry platform, where information is recorded upon administration. Informed consent for both vaccination and data processing was collected at the time of vaccination, in accordance with current national regulations. All data were processed exclusively by personnel of the Local Health Authority (LHA) of Viterbo, acting as data controller.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Demirdal T, Sen P, Emir B. Predictors of mortality in invasive pneumococcal disease: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. July 2021;19(7):927–44. [CrossRef]

- Wahl B, O’Brien KL, Greenbaum A, Majumder A, Liu L, Chu Y, et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000–15. Lancet Glob Health. June 13, 2018;6(7):e744–57. [CrossRef]

- Félix S, Handem S, Nunes S, Paulo AC, Candeias C, Valente C, et al. Impact of private use of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) on pneumococcal carriage among Portuguese children living in urban and rural regions. Vaccine. July 22, 2021;39(32):4524–33. [CrossRef]

- Schuchat A, Hilger T, Zell E, Farley MM, Reingold A, Harrison L, et al. Active bacterial core surveillance of the emerging infections program network. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(1):92–9. [CrossRef]

- De Wals P, Lefebvre B, Defay F, Deceuninck G, Boulianne N. Invasive pneumococcal diseases in birth cohorts vaccinated with PCV-7 and/or PHiD-CV in the province of Quebec, Canada. Vaccine. October 5, 2012;30(45):6416–20. [CrossRef]

- von Gottberg A, de Gouveia L, Tempia S, Quan V, Meiring S, von Mollendorf C, et al. Effects of vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease in South Africa. N Engl J Med. November 13, 2014;371(20):1889–99. [CrossRef]

- Gambia Pneumococcal Surveillance Group, Mackenzie GA, Hill PC, Jeffries DJ, Ndiaye M, Sahito SM, et al. Impact of the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia in The Gambia: 10 years of population-based surveillance. Lancet Infect Dis. September 2021;21(9):1293–302. [CrossRef]

- Fazio C. National surveillance of invasive bacterial diseases [Internet]. Rome: Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS); 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/meningite/pdf/RIS%202-2024.pdf.

- Monali R, De Vita E, Mariottini F, Privitera G, Lopalco PL, Tavoschi L. Impact of vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease in Italy 2007-2017: surveillance challenges and epidemiological changes. Epidemiol Infect. May 18, 2020;148:e187. [CrossRef]

- Italian Ministry of Health. National Immunization Prevention Plan (PNPV) 2012–2014 [Internet]. Rome: Ministry of Health; 2012 [cited 2025 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1721_allegato.pdf.

- Italian Ministry of Health. National Immunization Prevention Plan (PNPV) 2017–2019 [Internet]. Rome: Ministry of Health; 2017 [cited 2025 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf12.

- Falkenhorst G, Remschmidt C, Harder T, Hummers-Pradier E, Wichmann O, Bogdan C. Effectiveness of the 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine (PPV23) against Pneumococcal Disease in the Elderly: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS One. 2017;12(1):e0169368. [CrossRef]

- Italian Official Gazette. Determination no. 22A01494—VAXNEUVANCE approval [Internet]. 2022 Mar 8 [cited 2025 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.codiceRedazionale=22A01494&atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2022-03-08&elenco30giorni=false.

- Italian Official Gazette. Determination no. 23A00126 [Internet]. 2023 Jan 17 [cited 2025 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.codiceRedazionale=23A00126&atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2023-01-17&elenco30giorni=true.

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. National surveillance of invasive bacterial diseases. Data 2021–2023 [Internet]. Rome: ISS; 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/meningite/pdf/RIS%202-2024.pdf.

- Italian Official Gazette. Determination no. 22A02832 [Internet]. 2022 May 14 [cited 2025 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.codiceRedazionale=22A02832&atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2022-05-14.

- Italian Official Gazette. Determination no. 23A04549 [Internet]. 2023 Aug 17 [cited 2025 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.codiceRedazionale=23A04549&atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2023-08-17.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pneumococcal disease: vaccine recommendations [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/hcp/vaccine-recommendations/index.html.

- The Medical Letter, Inc. The Medical Letter® on Drugs and Therapeutics. Capvaxive—21-Val Pneumococcal Conjug Vaccine. 2024;66.

- Italian Ministry of Health. National Immunization Prevention Plan (PNPV) 2023–2025 [Internet]. Rome: Ministry of Health; 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.quotidianosanita.it/allegati/allegato1679488094.pdf.

- EpiCentro—Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Vaccination coverage in Italy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 20]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/vaccini/dati_Ita#pneumo.

- Regional Health Directorate, Emilia-Romagna. Vaccination coverage by birth cohort in Emilia-Romagna. Bologna: Emilia-Romagna Region; 2024.

- Sprenger R, Häckl D, Kossack N, Schiffner-Rohe J, Wohlleben J, von Eiff C. Pneumococcal vaccination rates in immunocompromised patients in Germany: A retrospective cohort study to assess sequential vaccination rates and changes over time. PLoS ONE. March 22, 2022;17(3):e0265433. [CrossRef]

- Cripps AW, Folaranmi T, Johnson KD, Musey L, Niederman MS, Buchwald UK. Immunogenicity following revaccination or sequential vaccination with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) in older adults and those at increased risk of pneumococcal disease: a review of the literature. Expert Rev Vaccines. March 2021;20(3):257–67. [CrossRef]

- Niederman MS, Folaranmi T, Buchwald UK, Musey L, Cripps AW, Johnson KD. Efficacy and effectiveness of a 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine against invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal disease and related outcomes: a review of available evidence. Expert Rev Vaccines. March 2021;20(3):243–56. [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo A, Martinelli A, Bianchi FP, Scazzi FL, Diella G, Tafuri S, et al. The safety of pneumococcal vaccines at the time of sequential schedule: data from surveillance of adverse events following 13-valent conjugated pneumococcal and 23-valent polysaccharidic pneumococcal vaccines in newborns and the elderly, in Puglia (Italy), 2013-2020. Ann Ig Med Prev E Comunita. 2023;35(4):459–67.

- Restivo V, Baldo V, Sticchi L, Senese F, Prandi GM, Pronk L, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Pneumococcal Vaccination in Adults in Italy: Comparing New Alternatives and Exploring the Role of GMT Ratios in Informing Vaccine Effectiveness. Vaccines. July 18, 2023;11(7):1253. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).