Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations and Convergence Analysis of Mixture of Experts

2.1. Function Approximation Capacity

2.2. Optimization Landscape and Convergence

2.3. Generalization Bounds

2.4. Open Problems and Future Directions

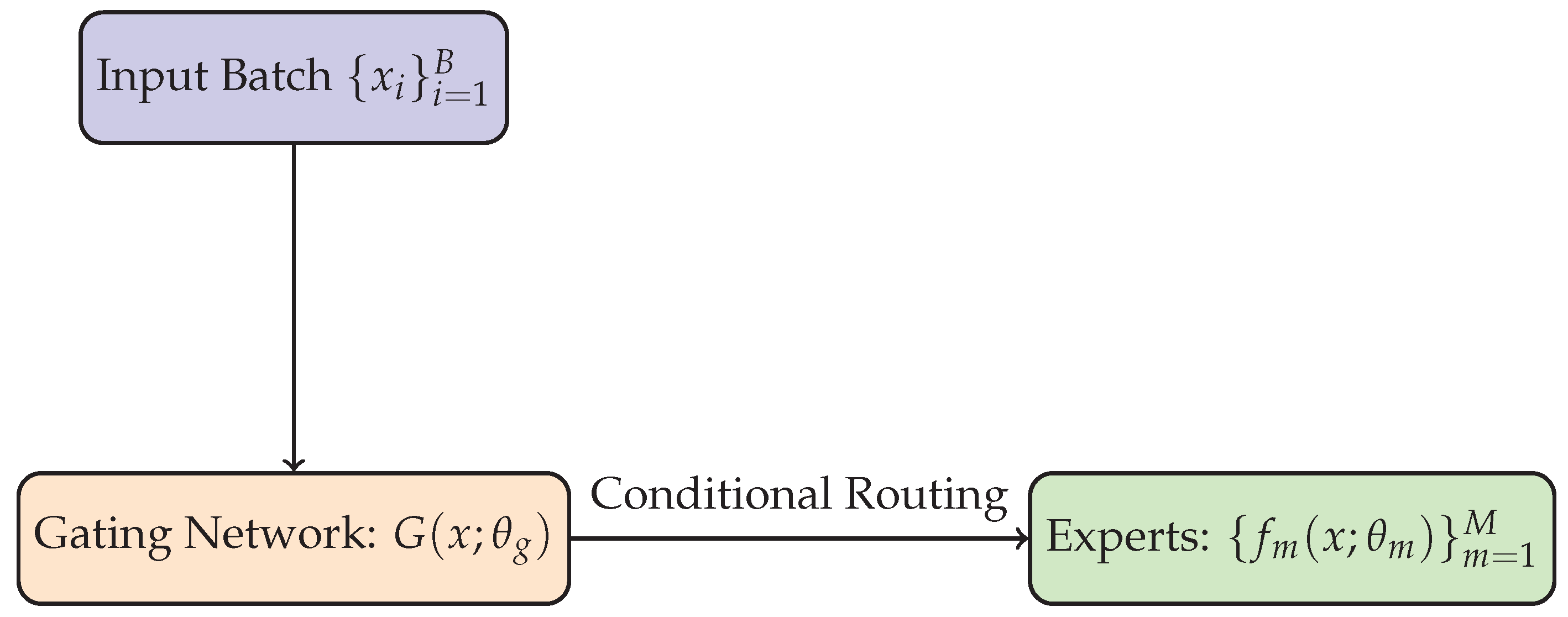

3. Architectural Foundations of Mixture of Experts

4. Training Paradigms and Optimization Challenges in Mixture of Experts

5. Explainability and Interpretability of Mixture of Experts

6. Efficiency Considerations and Scalability in Mixture of Experts

7. Applications and Case Studies of Mixture of Experts

7.1. Natural Language Processing

7.2. Computer Vision

7.3. Reinforcement Learning

7.4. Healthcare and Biomedical Informatics

7.5. Industrial and Systems Applications

7.6. Summary and Outlook

8. Conclusion

References

- Guanzheng Chen, Fangyu Liu, Zaiqiao Meng, and Shangsong Liang. Revisiting Parameter-Efficient Tuning: Are We Really There Yet? In Yoav Goldberg, Zornitsa Kozareva, and Yue Zhang, editors, Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2612–2626, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, December 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/2022.emnlp-main.168. URL https://aclanthology.org/2022.emnlp-main.168. [CrossRef]

- Dengchun Li, Yingzi Ma, Naizheng Wang, Zhiyuan Cheng, Lei Duan, Jie Zuo, Cal Yang, and Mingjie Tang. MixLoRA: Enhancing Large Language Models Fine-Tuning with LoRA based Mixture of Experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.15159, arXiv:2404.15159, 2024.

- Kang Min Yoo, Jaegeun Han, Sookyo In, Heewon Jeon, Jisu Jeong, Jaewook Kang, Hyunwook Kim, Kyung-Min Kim, Munhyong Kim, Sungju Kim, et al. HyperCLOVA X Technical Report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.01954, arXiv:2404.01954, 2024.

- Brandon McKinzie, Zhe Gan, Jean-Philippe Fauconnier, Sam Dodge, Bowen Zhang, Philipp Dufter, Dhruti Shah, Xianzhi Du, Futang Peng, Floris Weers, et al. Mm1: Methods, analysis & insights from multimodal llm pre-training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09611, arXiv:2403.09611, 2024.

- Zewen Chi, Li Dong, Shaohan Huang, Damai Dai, Shuming Ma, Barun Patra, Saksham Singhal, Payal Bajaj, Xia Song, Xian-Ling Mao, et al. On the representation collapse of sparse mixture of experts. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 34600–34613.

- Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, ukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Shwai He, Liang Ding, Daize Dong, Boan Liu, Fuqiang Yu, and Dacheng Tao. Pad-net: An efficient framework for dynamic networks. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 14354–14366, 2023.

- Vladislav Lialin, Vijeta Deshpande, and Anna Rumshisky. Scaling down to scale up: A guide to parameter-efficient fine-tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.15647, arXiv:2303.15647, 2023.

- Amjad Almahairi, Nicolas Ballas, Tim Cooijmans, Yin Zheng, Hugo Larochelle, and Aaron Courville. Dynamic capacity networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 2549–2558. PMLR, 2016.

- Ze Liu, Yutong Lin, Yue Cao, Han Hu, Yixuan Wei, Zheng Zhang, Stephen Lin, and Baining Guo. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pages 10012–10022, 2021.

- Tadas Baltrušaitis, Chaitanya Ahuja, and Louis-Philippe Morency. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2018, 41, 423–443.

- Tianlong Chen, Zhenyu Zhang, AJAY KUMAR JAISWAL, Shiwei Liu, and Zhangyang Wang. Sparse MoE as the New Dropout: Scaling Dense and Self-Slimmable Transformers. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023a. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=w1hwFUb_81.

- Zihao Zeng, Yibo Miao, Hongcheng Gao, Hao Zhang, and Zhijie Deng. Adamoe: Token-adaptive routing with null experts for mixture-of-experts language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.13233, arXiv:2406.13233, 2024.

- Samyam Rajbhandari, Jeff Rasley, Olatunji Ruwase, and Yuxiong He. Zero: Memory optimizations toward training trillion parameter models. In SC20: International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, pages 1–16. IEEE, 2020.

- Yanrui Du, Sendong Zhao, Danyang Zhao, Ming Ma, Yuhan Chen, Liangyu Huo, Qing Yang, Dongliang Xu, and Bing Qin. Mogu: A framework for enhancing safety of open-sourced llms while preserving their usability. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14488, arXiv:2405.14488, 2024.

- Zihan Qiu, Zeyu Huang, and Jie Fu. Unlocking emergent modularity in large language models. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 2638–2660, 2024.

- Hugo Touvron, Louis Martin, Kevin Stone, Peter Albert, Amjad Almahairi, Yasmine Babaei, Nikolay Bashlykov, Soumya Batra, Prajjwal Bhargava, Shruti Bhosale, et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288, arXiv:2307.09288, 2023.

- Ze-Feng Gao, Peiyu Liu, Wayne Xin Zhao, Zhong-Yi Lu, and Ji-Rong Wen. Parameter-efficient mixture-of-experts architecture for pre-trained language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.01104, arXiv:2203.01104, 2022.

- Robert A Jacobs, Michael I Jordan, Steven J Nowlan, and Geoffrey E Hinton. Adaptive mixtures of local experts. Neural computation 1991, 3, 79–87.

- Margaret Li, Suchin Gururangan, Tim Dettmers, Mike Lewis, Tim Althoff, Noah A Smith, and Luke Zettlemoyer. Branch-Train-Merge: Embarrassingly Parallel Training of Expert Language Models. In First Workshop on Interpolation Regularizers and Beyond at NeurIPS 2022, 2022a.

- Qwen Team. Introducing Qwen1.5, February 2024a. URL https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen1.5/.

- Ning Ding, Yujia Qin, Guang Yang, Fuchao Wei, Zonghan Yang, Yusheng Su, Shengding Hu, Yulin Chen, Chi-Min Chan, Weize Chen, et al. Delta tuning: A comprehensive study of parameter efficient methods for pre-trained language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.06904, arXiv:2203.06904, 2022.

- Zijian Zhang, Shuchang Liu, Jiaao Yu, Qingpeng Cai, Xiangyu Zhao, Chunxu Zhang, Ziru Liu, Qidong Liu, Hongwei Zhao, Lantao Hu, et al. M3oe: Multi-domain multi-task mixture-of experts recommendation framework. In Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, pages 893–902, 2024a.

- David Eigen, Marc’Aurelio Ranzato, and Ilya Sutskever. Learning factored representations in a deep mixture of experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.4314, arXiv:1312.4314, 2013.

- Rahaf Aljundi, Punarjay Chakravarty, and Tinne Tuytelaars. Expert gate: Lifelong learning with a network of experts. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 3366–3375, 2017.

- Noam Shazeer, Azalia Mirhoseini, Krzysztof Maziarz, Andy Davis, Quoc Le, Geoffrey Hinton, and Jeff Dean. Outrageously large neural networks: The sparsely-gated mixture-of-experts layer. arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.06538, arXiv:1701.06538, 2017.

- Angela Fan, Shruti Bhosale, Holger Schwenk, Zhiyi Ma, Ahmed El-Kishky, Siddharth Goyal, Mandeep Baines, Onur Celebi, Guillaume Wenzek, Vishrav Chaudhary, et al. Beyond english-centric multilingual machine translation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2021, 48.

- Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, Olga Golovneva, Vasu Sharma, Hu Xu, Xi Victoria Lin, Baptiste Rozière, Jacob Kahn, Daniel Li, Wen-tau Yih, Jason Weston, et al. Branch-Train-MiX: Mixing Expert LLMs into a Mixture-of-Experts LLM. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.07816, arXiv:2403.07816, 2024.

- Carlos Riquelme, Joan Puigcerver, Basil Mustafa, Maxim Neumann, Rodolphe Jenatton, André Susano Pinto, Daniel Keysers, and Neil Houlsby. Scaling vision with sparse mixture of experts. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 8583–8595.

- Yaqing Wang, Sahaj Agarwal, Subhabrata Mukherjee, Xiaodong Liu, Jing Gao, Ahmed Hassan Awadallah, and Jianfeng Gao. AdaMix: Mixture-of-Adaptations for Parameter-efficient Model Tuning. In Yoav Goldberg, Zornitsa Kozareva, and Yue Zhang, editors, Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 5744–5760, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, December 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/2022.emnlp-main.388. URL https://aclanthology.org/2022.emnlp-main.388. [CrossRef]

- Renrui Zhang, Jiaming Han, Chris Liu, Aojun Zhou, Pan Lu, Hongsheng Li, Peng Gao, and Yu Qiao. LLaMA-Adapter: Efficient Fine-tuning of Large Language Models with Zero-initialized Attention. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2024b. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=d4UiXAHN2W.

- Damai Dai, Chengqi Deng, Chenggang Zhao, RX Xu, Huazuo Gao, Deli Chen, Jiashi Li, Wangding Zeng, Xingkai Yu, Y Wu, et al. Deepseekmoe: Towards ultimate expert specialization in mixture-of-experts language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.06066, arXiv:2401.06066, 2024.

- Zhengyan Zhang, Zhiyuan Zeng, Yankai Lin, Chaojun Xiao, Xiaozhi Wang, Xu Han, Zhiyuan Liu, Ruobing Xie, Maosong Sun, and Jie Zhou. Emergent modularity in pre-trained transformers. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023, pages 4066–4083, 2023a.

- Jinguo Zhu, Xizhou Zhu, Wenhai Wang, Xiaohua Wang, Hongsheng Li, Xiaogang Wang, and Jifeng Dai. Uni-perceiver-moe: Learning sparse generalist models with conditional moes. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 2664–2678.

- Chenyu Jiang, Ye Tian, Zhen Jia, Shuai Zheng, Chuan Wu, and Yida Wang. Lancet: Accelerating Mixture-of-Experts Training via Whole Graph Computation-Communication Overlapping. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.19429, arXiv:2404.19429, 2024a.

- Tianwen Wei, Liang Zhao, Lichang Zhang, Bo Zhu, Lijie Wang, Haihua Yang, Biye Li, Cheng Cheng, Weiwei Lü, Rui Hu, et al. Skywork: A more open bilingual foundation model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.19341, arXiv:2310.19341, 2023.

- Shenggui Li, Fuzhao Xue, Chaitanya Baranwal, Yongbin Li, and Yang You. Sequence parallelism: Long sequence training from system perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.13120, arXiv:2105.13120, 2021.

- Xiao Ma, Liqin Zhao, Guan Huang, Zhi Wang, Zelin Hu, Xiaoqiang Zhu, and Kun Gai. Entire space multi-task model: An effective approach for estimating post-click conversion rate. In The 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, pages 1137–1140, 2018.

- Yikang Shen, Zhen Guo, Tianle Cai, and Zengyi Qin. JetMoE: Reaching Llama2 Performance with 0.1 M Dollars. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.07413, arXiv:2404.07413, 2024.

- Xin Wang, Fisher Yu, Lisa Dunlap, Yi-An Ma, Ruth Wang, Azalia Mirhoseini, Trevor Darrell, and Joseph E Gonzalez. Deep mixture of experts via shallow embedding. In Uncertainty in artificial intelligence, pages 552–562. PMLR, 2020.

- Shaohuai Shi, Xinglin Pan, Xiaowen Chu, and Bo Li. Pipemoe: Accelerating mixture-of-experts through adaptive pipelining. In IEEE INFOCOM 2023-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, pages 1–10. IEEE, 2023.

- Jie Ren, Samyam Rajbhandari, Reza Yazdani Aminabadi, Olatunji Ruwase, Shuangyan Yang, Minjia Zhang, Dong Li, and Yuxiong He. {Zero-offload}: Democratizing {billion-scale} model training. In 2021 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 21), pages 551–564, 2021.

- Xing Han, Huy Nguyen, Carl Harris, Nhat Ho, and Suchi Saria. FuseMoE: Mixture-of-Experts Transformers for Fleximodal Fusion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03226, arXiv:2402.03226, 2024.

- Do Huu Dat, Po Yuan Mao, Tien Hoang Nguyen, Wray Buntine, and Mohammed Bennamoun. HOMOE: A Memory-Based and Composition-Aware Framework for Zero-Shot Learning with Hopfield Network and Soft Mixture of Experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.14747, arXiv:2311.14747, 2023.

- Shagun Uppal, Sarthak Bhagat, Devamanyu Hazarika, Navonil Majumder, Soujanya Poria, Roger Zimmermann, and Amir Zadeh. Multimodal research in vision and language: A review of current and emerging trends. Information Fusion 2022, 77, 149–171.

- Luowei Zhou, Hamid Palangi, Lei Zhang, Houdong Hu, Jason Corso, and Jianfeng Gao. Unified vision-language pre-training for image captioning and vqa. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, volume 34, pages 13041–13049, 2020.

- Yongxin Guo, Zhenglin Cheng, Xiaoying Tang, and Tao Lin. Dynamic mixture of experts: An auto-tuning approach for efficient transformer models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14297, arXiv:2405.14297, 2024.

- Zonglin Li, Chong You, Srinadh Bhojanapalli, Daliang Li, Ankit Singh Rawat, Sashank J Reddi, Ke Ye, Felix Chern, Felix Yu, Ruiqi Guo, et al. The lazy neuron phenomenon: On emergence of activation sparsity in transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.06313, arXiv:2210.06313, 2022b.

- xAI. Grok-1, March 2024. URL https://github.com/xai-org/grok-1.

- Fuzhao Xue, Ziji Shi, Futao Wei, Yuxuan Lou, Yong Liu, and Yang You. Go wider instead of deeper. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 36, pages 8779–8787, 2022a.

- Yijiang Liu, Rongyu Zhang, Huanrui Yang, Kurt Keutzer, Yuan Du, Li Du, and Shanghang Zhang. Intuition-aware Mixture-of-Rank-1-Experts for Parameter Efficient Finetuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.08985, arXiv:2404.08985, 2024.

- William Fedus, Barret Zoph, and Noam Shazeer. Switch transformers: Scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2022, 39, 1–39.

- Mohammed Nowaz Rabbani Chowdhury, Shuai Zhang, Meng Wang, Sijia Liu, and Pin-Yu Chen. Patch-level routing in mixture-of-experts is provably sample-efficient for convolutional neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 6074–6114. PMLR, 2023.

- Shawn Tan, Yikang Shen, Zhenfang Chen, Aaron Courville, and Chuang Gan. Sparse Universal Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 169–179, 2023.

- Joshua Ainslie, James Lee-Thorp, Michiel de Jong, Yury Zemlyanskiy, Federico Lebron, and Sumit Sanghai. GQA: Training Generalized Multi-Query Transformer Models from Multi-Head Checkpoints. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 4895–4901, 2023.

- Joan Puigcerver, Carlos Riquelme Ruiz, Basil Mustafa, and Neil Houlsby. From Sparse to Soft Mixtures of Experts. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Yun Zhu, Nevan Wichers, Chu-Cheng Lin, Xinyi Wang, Tianlong Chen, Lei Shu, Han Lu, Canoee Liu, Liangchen Luo, Jindong Chen, et al. Sira: Sparse mixture of low rank adaptation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.09179, arXiv:2311.09179, 2023.

- Edward J Hu, Phillip Wallis, Zeyuan Allen-Zhu, Yuanzhi Li, Shean Wang, Lu Wang, Weizhu Chen, et al. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021.

- Szymon Antoniak, Sebastian Jaszczur, Michał Krutul, Maciej Pióro, Jakub Krajewski, Jan Ludziejewski, Tomasz Odrzygóźdź, and Marek Cygan. Mixture of Tokens: Efficient LLMs through Cross-Example Aggregation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.15961, arXiv:2310.15961, 2023.

- Yihua Zhang, Ruisi Cai, Tianlong Chen, Guanhua Zhang, Huan Zhang, Pin-Yu Chen, Shiyu Chang, Zhangyang Wang, and Sijia Liu. Robust Mixture-of-Expert Training for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pages 90–101, 2023b.

- Shizhe Diao, Tianyang Xu, Ruijia Xu, Jiawei Wang, and Tong Zhang. Mixture-of-Domain-Adapters: Decoupling and Injecting Domain Knowledge to Pre-trained Language Models’ Memories. In The 61st Annual Meeting Of The Association For Computational Linguistics, 2023.

- Samyam Rajbhandari, Olatunji Ruwase, Jeff Rasley, Shaden Smith, and Yuxiong He. Zero-infinity: Breaking the gpu memory wall for extreme scale deep learning. In Proceedings of the international conference for high performance computing, networking, storage and analysis, pages 1–14, 2021.

- Shaoxiang Chen, Zequn Jie, and Lin Ma. Llava-mole: Sparse mixture of lora experts for mitigating data conflicts in instruction finetuning mllms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16160, arXiv:2401.16160, 2024.

- Yassine Zniyed, Thanh Phuong Nguyen, et al. Efficient tensor decomposition-based filter pruning. Neural Networks 2024, 178, 106393. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronald J Williams. Simple statistical gradient-following algorithms for connectionist reinforcement learning. Machine learning 1992, 8, 229–256. [CrossRef]

- Lucas Theis and Matthias Bethge. Generative image modeling using spatial lstms. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 28.

- Wuyang Chen, Yanqi Zhou, Nan Du, Yanping Huang, James Laudon, Zhifeng Chen, and Claire Cui. Lifelong language pretraining with distribution-specialized experts. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 5383–5395. PMLR, 2023b.

- Jiquan Ngiam, Aditya Khosla, Mingyu Kim, Juhan Nam, Honglak Lee, and Andrew Y Ng. Multimodal deep learning. In Proceedings of the 28th international conference on machine learning (ICML-11), pages 689–696, 2011.

- Andrew Davis and Itamar Arel. Low-rank approximations for conditional feedforward computation in deep neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.4461, arXiv:1312.4461, 2013.

- Ted Zadouri, Ahmet Üstün, Arash Ahmadian, Beyza Ermiş, Acyr Locatelli, and Sara Hooker. Pushing mixture of experts to the limit: Extremely parameter efficient moe for instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.05444, arXiv:2309.05444, 2023.

- Siddharth Singh, Olatunji Ruwase, Ammar Ahmad Awan, Samyam Rajbhandari, Yuxiong He, and Abhinav Bhatele. A Hybrid Tensor-Expert-Data Parallelism Approach to Optimize Mixture-of-Experts Training. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Supercomputing, pages 203–214, 2023.

- Aakanksha Chowdhery, Sharan Narang, Jacob Devlin, Maarten Bosma, Gaurav Mishra, Adam Roberts, Paul Barham, Hyung Won Chung, Charles Sutton, Sebastian Gehrmann, et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2023; 24, 1–113.

- Aidan Clark, Diego de Las Casas, Aurelia Guy, Arthur Mensch, Michela Paganini, Jordan Hoffmann, Bogdan Damoc, Blake Hechtman, Trevor Cai, Sebastian Borgeaud, et al. Unified scaling laws for routed language models. In International conference on machine learning, pages 4057–4086. PMLR, 2022.

- Long Ouyang, Jeffrey Wu, Xu Jiang, Diogo Almeida, Carroll Wainwright, Pamela Mishkin, Chong Zhang, Sandhini Agarwal, Katarina Slama, Alex Ray, et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 27730–27744.

- Woosuk Kwon, Zhuohan Li, Siyuan Zhuang, Ying Sheng, Lianmin Zheng, Cody Hao Yu, Joseph Gonzalez, Hao Zhang, and Ion Stoica. Efficient memory management for large language model serving with pagedattention. In Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, pages 611–626, 2023.

- Weilin Cai, Juyong Jiang, Le Qin, Junwei Cui, Sunghun Kim, and Jiayi Huang. Shortcut-connected Expert Parallelism for Accelerating Mixture-of-Experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.05019, arXiv:2404.05019, 2024.

- Aran Komatsuzaki, Joan Puigcerver, James Lee-Thorp, Carlos Riquelme Ruiz, Basil Mustafa, Joshua Ainslie, Yi Tay, Mostafa Dehghani, and Neil Houlsby. Sparse Upcycling: Training Mixture-of-Experts from Dense Checkpoints. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022.

- Jingwei Xu, Junyu Lai, and Yunpeng Huang. Meteora: Multiple-tasks embedded lora for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.13053, arXiv:2405.13053, 2024.

- Fuzhao Xue, Xiaoxin He, Xiaozhe Ren, Yuxuan Lou, and Yang You. One student knows all experts know: From sparse to dense. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.10890, arXiv:2201.10890, 2022b.

- LLaMA-MoE Team. LLaMA-MoE: Building Mixture-of-Experts from LLaMA with Continual Pre-training, Dec 2023. URL https://github.com/pjlab-sys4nlp/llama-moe.

- David Raposo, Sam Ritter, Blake Richards, Timothy Lillicrap, Peter Conway Humphreys, and Adam Santoro. Mixture-of-Depths: Dynamically allocating compute in transformer-based language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.02258, arXiv:2404.02258, 2024.

- Qwen Team. Qwen1.5-MoE: Matching 7B Model Performance with 1/3 Activated Parameters", February 2024b. URL https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen-moe/.

- Yassine Zniyed, Thanh Phuong Nguyen, et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2024.

- Xiang Lisa Li and Percy Liang. Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4582–4597, 2021.

- Xiaonan Nie, Pinxue Zhao, Xupeng Miao, Tong Zhao, and Bin Cui. HetuMoE: An efficient trillion-scale mixture-of-expert distributed training system. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.14685, arXiv:2203.14685, 2022.

- Yongqi Huang, Peng Ye, Xiaoshui Huang, Sheng Li, Tao Chen, and Wanli Ouyang. Experts weights averaging: A new general training scheme for vision transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.06093, arXiv:2308.06093, 2023.

- Jason Wei, Yi Tay, Rishi Bommasani, Colin Raffel, Barret Zoph, Sebastian Borgeaud, Dani Yogatama, Maarten Bosma, Denny Zhou, Donald Metzler, et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07682, arXiv:2206.07682, 2022.

- Mikel Artetxe, Shruti Bhosale, Naman Goyal, Todor Mihaylov, Myle Ott, Sam Shleifer, Xi Victoria Lin, Jingfei Du, Srinivasan Iyer, Ramakanth Pasunuru, et al. Efficient large scale language modeling with mixtures of experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.10684, arXiv:2112.10684, 2021.

- Databricks. Introducing DBRX: A New State-of-the-Art Open LLM, March 2024. URL https://www.databricks.com/blog/introducing-dbrx-new-state-art-open-llm.

- Shaohuai Shi, Xinglin Pan, Qiang Wang, Chengjian Liu, Xiaozhe Ren, Zhongzhe Hu, Yu Yang, Bo Li, and Xiaowen Chu. Schemoe: An extensible mixture-of-experts distributed training system with tasks scheduling. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth European Conference on Computer Systems, pages 236–249, 2024.

- Yanping Huang, Youlong Cheng, Ankur Bapna, Orhan Firat, Dehao Chen, Mia Chen, HyoukJoong Lee, Jiquan Ngiam, Quoc V Le, Yonghui Wu, et al. Gpipe: Efficient training of giant neural networks using pipeline parallelism. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2019; 32.

- Shihan Dou, Enyu Zhou, Yan Liu, Songyang Gao, Jun Zhao, Wei Shen, Yuhao Zhou, Zhiheng Xi, Xiao Wang, Xiaoran Fan, et al. The Art of Balancing: Revolutionizing Mixture of Experts for Maintaining World Knowledge in Language Model Alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.09979, arXiv:2312.09979, 2023.

- Neil Houlsby, Andrei Giurgiu, Stanislaw Jastrzebski, Bruna Morrone, Quentin De Laroussilhe, Andrea Gesmundo, Mona Attariyan, and Sylvain Gelly. Parameter-efficient transfer learning for NLP. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 2790–2799. PMLR, 2019.

- Barret Zoph, Irwan Bello, Sameer Kumar, Nan Du, Yanping Huang, Jeff Dean, Noam Shazeer, and William Fedus. St-moe: Designing stable and transferable sparse expert models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.08906, arXiv:2202.08906, 2022.

- Albert Q Jiang, Alexandre Sablayrolles, Antoine Roux, Arthur Mensch, Blanche Savary, Chris Bamford, Devendra Singh Chaplot, Diego de las Casas, Emma Bou Hanna, Florian Bressand, et al. Mixtral of experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.04088, arXiv:2401.04088, 2024b.

- James Kirkpatrick, Razvan Pascanu, Neil Rabinowitz, Joel Veness, Guillaume Desjardins, Andrei A Rusu, Kieran Milan, John Quan, Tiago Ramalho, Agnieszka Grabska-Barwinska, et al. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 3521, 114, 3521–3526.

- Opher Lieber, Barak Lenz, Hofit Bata, Gal Cohen, Jhonathan Osin, Itay Dalmedigos, Erez Safahi, Shaked Meirom, Yonatan Belinkov, Shai Shalev-Shwartz, et al. Jamba: A hybrid transformer-mamba language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.19887, arXiv:2403.19887, 2024.

- Changho Hwang, Wei Cui, Yifan Xiong, Ziyue Yang, Ze Liu, Han Hu, Zilong Wang, Rafael Salas, Jithin Jose, Prabhat Ram, et al. Tutel: Adaptive mixture-of-experts at scale. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 2023, 5.

- Yoshua Bengio, Nicholas Léonard, and Aaron Courville. Estimating or propagating gradients through stochastic neurons for conditional computation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1308.3432, arXiv:1308.3432, 2013.

- Hongyi Wang, Felipe Maia Polo, Yuekai Sun, Souvik Kundu, Eric Xing, and Mikhail Yurochkin. Fusing Models with Complementary Expertise. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Clemens Rosenbaum, Tim Klinger, and Matthew Riemer. Routing networks: Adaptive selection of non-linear functions for multi-task learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.01239, arXiv:1711.01239, 2017.

- Yunhao Gou, Zhili Liu, Kai Chen, Lanqing Hong, Hang Xu, Aoxue Li, Dit-Yan Yeung, James T Kwok, and Yu Zhang. Mixture of cluster-conditional lora experts for vision-language instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.12379, arXiv:2312.12379, 2023.

- Sam Ade Jacobs, Masahiro Tanaka, Chengming Zhang, Minjia Zhang, Leon Song, Samyam Rajbhandari, and Yuxiong He. Deepspeed ulysses: System optimizations for enabling training of extreme long sequence transformer models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.14509, arXiv:2309.14509, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).