Introduction

Organophosphate (OP) poisoning, primarily resulting from pesticide exposure, is a well-documented cause of autonomic dysfunction, neuromuscular impairment, and cardiovascular complications [

1]. However, acute atrial fibrillation (AF) as a direct consequence of OP poisoning is a rare clinical manifestation. Atrial fibrillation is an unusual cardiac manifestation of organophosphate poisoning, often triggered by autonomic dysfunction and excessive vagal stimulation [

2]. Organophosphates exert their toxic effects by irreversibly inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, leading to an excessive accumulation of acetylcholine at synapses [

3]. This cholinergic overactivity can precipitate a spectrum of cardiovascular abnormalities, including bradyarrhythmia’s, QT prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias, and, in rare cases, atrial fibrillation.

The underlying mechanisms may involve autonomic nervous system imbalance, direct myocardial toxicity, electrolyte disturbances, and oxidative stress [

4]. While AF is often associated with structural heart disease, metabolic disturbances, and systemic inflammation, toxicological causes are less frequently reported. Acute cardiac arrhythmias, ranging from bradycardia to AF, are common in organophosphate poisoning due to excessive cholinergic stimulation [

2]. Diagnosis relies on clinical history, ECG findings, and tests like serum cholinesterase levels [

5]. Treatment involves reversing poisoning with atropine and pralidoxime, while managing arrhythmias with rate control or electrical cardioversion as needed [

6]. This case report describes a rare presentation of acute atrial fibrillation triggered by organophosphate poisoning. The report highlights the clinical features, diagnostic approach, and management strategies employed, emphasizing the need for early recognition and intervention to prevent potential complications.

Case Presentation

The patient was a 53-year-old female housewife who was brought to the emergency department by neighbors who found her unconscious. She had been last seen in stable condition the previous evening. She had ingested an unknown quantity of a 35% emulsified concentration of endosulfan pesticide approximately four and a half hours prior to arrival. Upon arrival, she exhibited profound cholinergic toxicity, including miosis, hypersalivation, lacrimation, muscle fasciculations, bradycardia followed by tachyarrhythmia, hypertension transitioning into hypotension, and respiratory distress. Her symptoms worsened rapidly, and an irregularly irregular tachycardia was detected. She had no history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, or thyroid dysfunction. She had never been diagnosed with arrhythmias or structural heart disease. She had no previous episodes of poisoning or psychiatric illnesses, was not taking any regular medications, and had no known drug allergies. There was no history of cardiovascular diseases, arrhythmias, or sudden cardiac death in her family. No familial predisposition to pesticide toxicity was reported. The patient had been living alone after divorcing her husband. She had no known history of smoking, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. However, she had been experiencing significant financial difficulties and psychological distress, raising concerns about possible self-harm. She had no occupational exposure to pesticides.

On general examination, the patient appeared disoriented, restless, and in respiratory distress. Her skin was cold and clammy, with increased sweating. Her vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 97/65 mmHg, a heart rate of 129 beats per minute with an irregular rhythm, a respiratory rate of 25 breaths per minute, an oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, and a body temperature of 36.8°C. Neurological examination showed altered mental status, muscle twitching, and hyperreflexia. Cardiovascular examination revealed an irregularly irregular pulse, no murmurs, and mild peripheral edema. Respiratory examination showed bilateral crackles, suggesting pulmonary congestion, along with signs of mild respiratory distress. Gastrointestinal examination revealed abdominal tenderness and hyperactive bowel sounds.

A range of biochemical, hematological, and toxicological tests were performed to evaluate systemic involvement and confirm the diagnosis. The patient’s white blood cell count was elevated at 13,200/mm3. Hemoglobin (12.9 g/dL) and platelet count (182,600/mm3) were within normal limits. The patient’s sodium level was 137 mmol/L (normal range = 135-145 mEq/L), and magnesium 2.1 mg/dL (normal value = 1.7-2.2 mg/dL), within the normal range. Potassium was 2.8 mmol/L (normal range = 3.5-5.0 mEq/L), which was low, and critical. Serum creatinine (1.0 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen (16 mg/dL) were within normal limits. The patient’s aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 147 U/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 136 U/L. Total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels were normal. The results showed a pH of 7.14, partial carbon dioxide of 59 mmHg, and bicarbonate of 11 mmol/L. The patient’s cholinesterase level was 2,430 U/L (reference range: 5,000-12,000 U/L). The patient’s troponin I was 0.13 ng/mL (reference range <0.04 ng/mL), and creatine kinase-MB was within normal limits. The patient’s thyroid-stimulating hormone was 1.9 µIU/mL, and free T4 was 0.9 ng/dL. The toxicological results were positive for organophosphate compounds, specifically endosulfan. The patient’s prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio were all within normal ranges. The patient’s random blood glucose was 89 mg/dL, within the normal range.

Electrocardiography (ECG) confirmed atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response, with no evidence of ST-segment elevation or ischemic changes. QT prolongation was noted. Chest X-ray showed pulmonary congestion without signs of aspiration pneumonia. Echocardiography demonstrated normal left ventricular function with no structural abnormalities. A brain CT scan was performed to rule out stroke due to the new-onset atrial fibrillation but showed no acute ischemic changes. The CT scan showed no evidence of bleeding. Based on the clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and ECG results, the patient was diagnosed with acute atrial fibrillation secondary to organophosphate poisoning due to endosulfan ingestion.

The patient was immediately admitted to the intensive care unit for close monitoring and supportive management. Airway protection was ensured, and she was placed on oxygen therapy via nasal cannula at 4 L/min. Due to respiratory distress, she was subsequently intubated and mechanically ventilated. She received 20 mL/kg intravenous fluids (normal saline) to maintain hemodynamic stability. She was given atropine as a 2 mg IV bolus, repeated every 5 minutes until secretions decreased, followed by continuous infusion. Pralidoxime (2-PAM) was administered at an initial dose of 1 g IV over 30 minutes, followed by continuous infusion for 24 hours. She received 10 mg /hour of potassium chloride intravenously for 12 hours and after serum potassium ≥ 3.0 mEq/L changed to 10 mEq of potassium supplementation orally once daily for 3 days and discontinued it after her hypokalemia was corrected. Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers were avoided due to concerns about exacerbating hypotension. For atrial fibrillation, she received IV amiodarone for rate control. Due to the acute nature of the poisoning, rhythm control was not attempted initially, and electrical cardioversion was avoided. Anticoagulation was withheld due to the uncertain thromboembolic risk in acute, toxin-mediated AF, underlining the complexity of balancing bleeding risks in poisoned patients. She received diazepam prophylactically to prevent seizures.

The patient remained in the ICU for 60 hours, during which she showed gradual improvement. Spontaneous conversion to normal sinus rhythm occurred after 36 hours without requiring electrical cardioversion. By day 2, she was weaned off ventilatory support and transferred to the general ward. A psychiatric evaluation was conducted, revealing severe emotional distress but no underlying psychiatric disorder. She was discharged on day 8 with appropriate counseling, monthly follow-up with a cardiologist, and a psychiatrist.

Discussion

Organophosphate poisoning primarily affects the nervous system through excessive cholinergic stimulation. Cardiovascular manifestations, though less common, include arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, and myocardial dysfunction [

7]. Acute AF caused by organophosphate poisoning is a rare but significant complication [

8]. Organophosphates like endosulfan, a widely used pesticide, inhibit acetylcholinesterase, leading to the accumulation of acetylcholine at nerve synapses and overstimulation of muscarinic and nicotinic receptors [

9]. This disruption in neurotransmission can result in a range of clinical manifestations, including cardiovascular arrhythmias such as AF. The typical clinical manifestations of acute organophosphate poisoning include muscarinic effects such as excessive salivation, sweating, nausea, vomiting, and bradycardia, as well as nicotine-like effects such as muscle twitching, fasciculations, and weakness. Central nervous system symptoms may range from confusion to seizures or coma [

10]. In this case, the 56-year-old woman, after ingesting the pesticide, likely presents with these classical symptoms alongside atrial fibrillation. This arrhythmia may be worsened by underlying electrolyte imbalances (e.g., hypokalemia) and acidosis, which are common in poisoning scenarios.

Previous case reports of organophosphate poisoning rarely emphasize AF as a primary clinical manifestation. Typically, organophosphate poisoning leads to muscarinic and nicotinic symptoms (e.g., bradycardia, miosis, salivation, and muscle weakness) [

11]. However, cases of arrhythmias, including AF, are documented, though less common, and might result from severe poisoning or concurrent comorbidities. Typically, organophosphate poisoning leads to symptoms like nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and, in severe cases, respiratory distress [

5]. However, this peculiar case also presents with acute AF, which may be related to electrolyte imbalances, hypoxia, or autonomic dysfunction caused by the poisoning. Organophosphate poisoning primarily works by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, leading to the excessive buildup of acetylcholine [

2]. This overstimulation of muscarinic receptors in the heart results in an increase in vagal tone, which typically causes bradycardia. However, direct myocardial toxicity and resultant disturbances in electrolyte homeostasis can predispose the heart to arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation. Altered action potentials, particularly from disruptions in calcium and potassium channels, contribute to the development of AF [

12].

Atrial fibrillation can manifest in three main forms: paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent [

13]. Paroxysmal AF occurs in episodes that resolve spontaneously, while persistent AF requires medical intervention for conversion to sinus rhythm. Permanent AF refers to a chronic state where the arrhythmia persists despite attempts at cardioversion. In the case of organophosphate poisoning, the AF is likely paroxysmal, directly linked to the acute toxicity of the pesticide, although it may progress to persistent or permanent AF if left untreated. In this case report, the patient experienced paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after ingesting endosulfan organophosphate poisoning. While bradycardia is more commonly observed in organophosphate poisoning due to parasympathetic overdrive, acute AF has been reported in some severe cases [

11]. It is generally considered a rare complication but can occur in individuals with severe poisoning or specific risk factors, such as age, heart disease, or electrolyte disturbances. The patient developed acute atrial fibrillation, which is a transient arrhythmia that might occur during or after poisoning. The mechanism could involve both direct effects on the heart’s electrical system from acetylcholine and secondary effects from metabolic disturbances.

Pathophysiological, organophosphate poisoning usually causes bradycardia due to excessive parasympathetic stimulation [

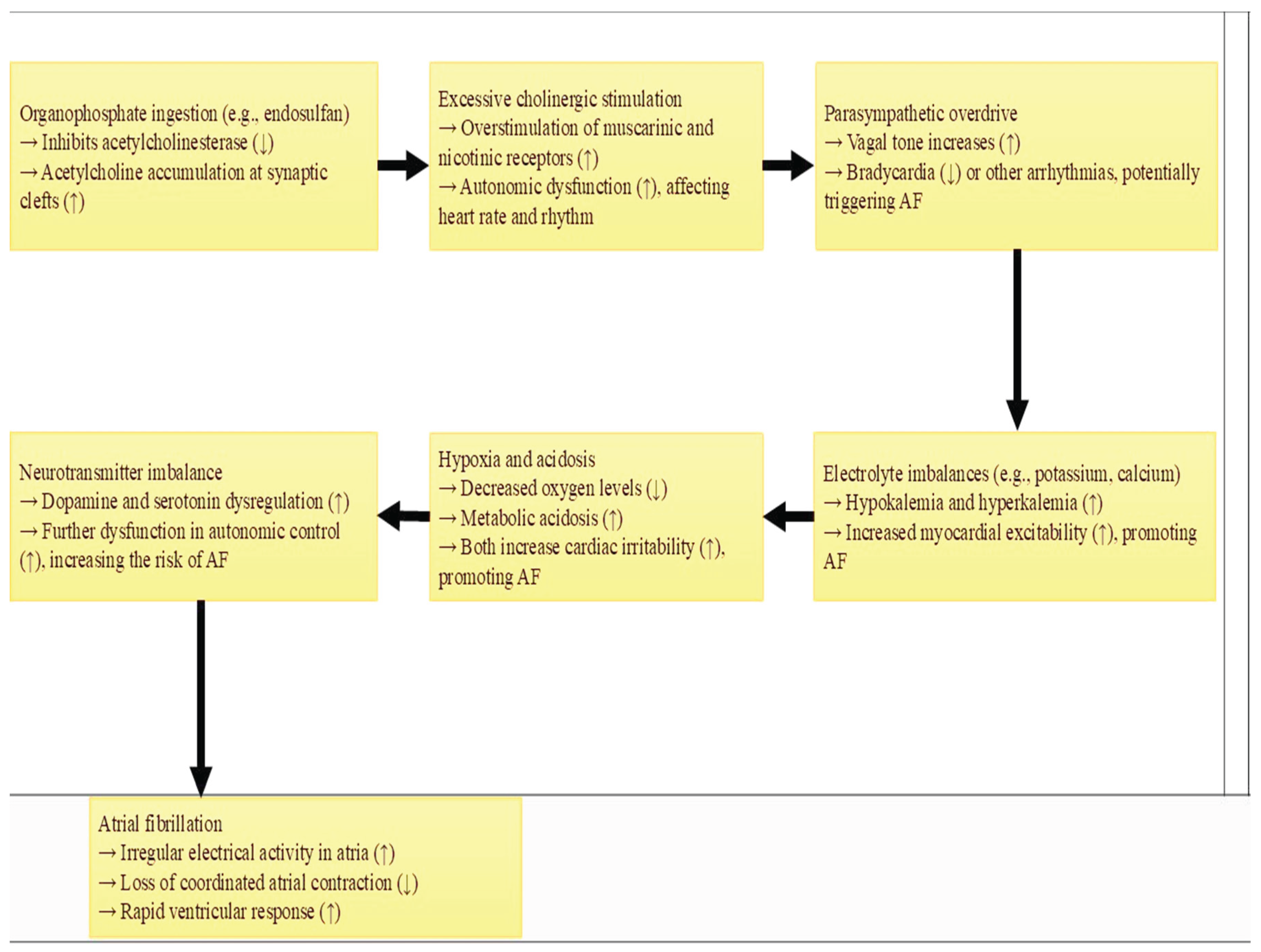

7]. However, more severe cases may result in dysrhythmias such as AF, often in individuals with predisposing conditions like electrolyte imbalances or underlying cardiac disease. Organophosphates like endosulfan inhibit acetylcholinesterase, leading to the accumulation of acetylcholine at synaptic clefts (

Figure 1). Organophosphates inhibit acetylcholinesterase, leading to excessive acetylcholine, which can trigger parasympathetic overactivity and potentially disrupt cardiac conduction, leading to AF [

4]. Oxidative stress and electrolyte imbalances, especially hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia, could further contribute to arrhythmias [

14]. This causes overstimulation of both muscarinic and nicotinic receptors, disrupting autonomic control over the heart and possibly precipitating AF. Additionally, the imbalance in electrolytes, hypoxia, and acidosis resulting from severe poisoning can trigger arrhythmias.

The diagnosis of AF in the setting of organophosphate toxicity requires a high index of suspicion and timely recognition of other poisoning symptoms. An ECG is essential for confirming the presence of AF, which is characterized by an irregularly irregular rhythm and the absence of P waves [

15]. The diagnosis of organophosphate poisoning is largely clinical and requires a detailed history of pesticide exposure, such as ingestion of endosulfan. Laboratory tests, such as serum cholinesterase levels, can confirm exposure to organophosphates, while arterial blood gases can assess acid-base disturbances and electrolyte imbalances.

Standard treatment includes atropine to counteract parasympathetic effects, and if arrhythmias like AF are detected, pharmacologic agents such as amiodarone or electrical cardioversion might be employed. However, in most existing case reports, the focus is typically on treating the poisoning rather than specifically managing AF unless it becomes life-threatening. Treatment would involve the usual management of organophosphate poisoning, including atropine to reverse muscarinic effects and pralidoxime to reactivate acetylcholinesterase [

16]. The management of AF in this context would require rate control (e.g., beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers) and careful monitoring of electrolytes and oxygenation [

17]. The prognosis in cases of severe organophosphate poisoning with arrhythmias largely depends on early diagnosis and treatment. Those with AF due to organophosphate poisoning generally have a more favorable prognosis, though the risk of sudden death or other complications due to the underlying toxicity or arrhythmia still exists. The prognosis in this case depends on the severity of the poisoning and the speed of intervention. If treated promptly with appropriate antidotes and supportive care, recovery from both poisoning and AF is possible [

18]. However, the presence of AF may increase the risk of complications such as stroke or hemodynamic instability.

The new case report on OP poisoning compares an unusual presentation with acute AF to many existing reports that typically describe AF alongside clinical manifestations like bradycardia, tachycardia, or QT prolongation. While both cases involve cholinergic symptoms managed with atropine (0.02–0.08 mg/kg/hr) and pralidoxime (10–20 mg/kg/hr), the AF case required higher atropine doses and additional rate control measures. This case underscores the need for tailored cardiac interventions in OP poisoning and reinforces the importance of continuous cardiac assessment. Existing literature regarding AF typically uses beta blockers or calcium channel blockers for rate control; however, in this case report, the patient received amiodarone cautiously to avoid exaggerated hypotension (

Table 1).

Strengths and Limitations of the Case Report

The report highlights an uncommon complication of organophosphate poisoning, specifically the onset of acute AF, adding new insight into its potential cardiovascular effects. The case report offers a detailed exploration of the mechanisms through which organophosphate toxicity can contribute to arrhythmias, particularly AF, involving autonomic dysfunction, electrolyte imbalances, and other metabolic disturbances. As a single case report, the findings are limited in terms of generalizability to the broader population. The report does not provide long-term follow-up on the patient’s recovery, including the persistence or recurrence of AF after initial treatment.

Key Points

This case presents a unique and clinically significant manifestation of acute organophosphate poisoning with the development of atrial fibrillation, a rarely reported complication. The patient’s atrial fibrillation developed in the absence of underlying cardiovascular disease or structural heart abnormalities, indicating a direct toxic effect of the OP compound on cardiac conduction. Importantly, this case demonstrates that organophosphate-induced AF can be transient and reversible with appropriate antidotal and supportive therapy.

Conclusion

Organophosphate poisoning can trigger acute atrial fibrillation, highlighting the need for careful cardiovascular monitoring in such cases. The development of AF in this context is likely multifactorial—driven by autonomic dysfunction, direct myocardial toxicity, oxidative stress, and associated metabolic derangements such as hypokalemia and acidosis. Early intervention, including the use of atropine and other supportive treatments, is crucial for preventing severe complications like AF and ensuring better patient outcomes. In this case due to the patient’s hemodynamic instability and risk of exacerbated hypotension, commonly used rate control agents like beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers were avoided. Instead, amiodarone was carefully selected, marking a deviation from standard protocols and highlighting the need for individualized treatment in toxicological emergencies.

Author Contributions

GB: Conceptualization, curating the data, investigation, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, critical review and editing of the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from a patient for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Further detail about the report can be made available by request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ramadori, G.P. Organophosphorus Poisoning: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) and Cardiac Failure as Cause of Death in Hospitalized Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, N. Exploring the effect of organophosphate (OP) pesticide exposure on the development of the autonomic stress response in the children of agricultural workers (Doctoral dissertation, Iowa State University).

- Pulkrabkova, L.; Svobodova, B.; Konecny, J.; Kobrlova, T.; Muckova, L.; Janousek, J.; Pejchal, J.; Korabecny, J.; Soukup, O. Neurotoxicity evoked by organophosphates and available countermeasures. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 97, 39–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladěnka, P.; Applová, L.; Patočka, J.; Costa, V.M.; Remiao, F.; Pourová, J.; Mladěnka, A.; Karlíčková, J.; Jahodář, L.; Vopršalová, M.; et al. Comprehensive review of cardiovascular toxicity of drugs and related agents. Med. Res. Rev. 2018, 38, 1332–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T.; Arai, Y.; Yuasa, S.; Abe, Y.; Takayama, M.; Sasaki, T.; Kunitomi, A.; Inagaki, H.; Endo, M.; Morinaga, J.; et al. Associations of cardiovascular biomarkers and plasma albumin with exceptional survival to the highest ages. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong M, Cleveland E. Envenomation, Poisoning, and Toxicology. Surgical Critical Care and Emergency Surgery: Clinical Questions and Answers. 2022 Jun 24:261-72.

- Pannu, A.K.; Bhalla, A.; I Vishnu, R.; Garg, S.; Dhibar, D.P.; Sharma, N.; Vijayvergiya, R. Cardiac injury in organophosphate poisoning after acute ingestion. Toxicol. Res. 2021, 10, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorhead, JC. Nervous System Disorders. Essentials of Emergency Medicine. 2010 Oct 22:371.

- Madhani, N.B. , King, A.M., Menke, N.B., et al. Abesamis, M. and Pizon, A.F., 2014. 70. Non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction after phenylephrine misdosing. In XXXIV International Congress of the European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists (EAPCCT) , Brussels, Belgium (Vol. 52, No. 4, p. 323). 27–30 May.

- Bereda, G. Poisoning by Organophosphate Pesticides: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14, e29842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavonas, E.J.; Akpunonu, P.D.; Arens, A.M.; Babu, K.M.; Cao, D.; Hoffman, R.S.; Hoyte, C.O.; Mazer-Amirshahi, M.E.; Stolbach, A.; St-Onge, M.; et al. 2023 American Heart Association Focused Update on the Management of Patients With Cardiac Arrest or Life-Threatening Toxicity Due to Poisoning: An Update to the American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2023, 148, E149–E184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Villar, J.D.; Petronilho, E.C.; Kuca, K.; Franca, T.C.C. Review about Structure and Evaluation of Reactivators of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibited with Neurotoxic Organophosphorus Compounds. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 1422–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenasa M, Camm AJ, editors. Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press, USA; 2015.

- Negru, A.G.; Pastorcici, A.; Crisan, S.; Cismaru, G.; Popescu, F.G.; Luca, C.T. The Role of Hypomagnesemia in Cardiac Arrhythmias: A Clinical Perspective. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, N. 40th International Congress of the European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists (EAPCCT) 19-22 May 2020, Tallinn, Estonia. Clin. Toxicol. 2020, 58, 505–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey RD, Grant AO. 14 Agents Used in Cardiac Arrhythmias. Basic & clinical pharmacology. 2018:228.

- Bar-Meir, E.; Schein, O.; Eisenkraft, A.; Rubinshtein, R.; Grubstein, A.; Militianu, A.; Glikson, M. Guidelines for Treating Cardiac Manifestations of Organophosphates Poisoning with Special Emphasis on Long QT and Torsades De Pointes. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2007, 37, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-S.; Yen, C.-C.; Wu, C.-I.; Li, Y.-H.; Chen, J.-Y. Organophosphate poisoning presenting as out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A clinical challenge. J. Cardiol. Cases 2017, 16, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwari, M.; Chaudhary, S. Acute atrial fibrillation complicating organophosphorus poisoning. Hear. Views 2017, 18, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelnaby, MH. Acute atrial fibrillation induced by organophosphorus poisoning: case report. Journal of Clinical Toxicology. 2018;8(1):1-2.

- Patel, S.; Mathew, R.; Patel, R. Atrial Fibrillation: A Rare ECG Finding in Organophosphate Poisoning. Mathews J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faluomi, M.; Cialini, M.; Naviganti, M.; Mastromauro, A.; Marinangeli, F.; Angeletti, C. Organophosphates pesticide poisoning: a peculiar case report. J. Emerg. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 6, 30–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).