Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cybersecurity Readiness of SMEs

2.2. Cyber Risks of SMEs

2.3. Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process

2.4. Factors Influencing the Cybersecurity Readiness Capability

2.4.1. Personnel Readiness

2.4.2. Process Readiness

2.4.3. Technology Readiness

3. Methodology

3.1. Fuzzy AHP

3.1.1. Planning

3.1.2. AHP Execution

- Pairwise Comparison: Experts evaluate the relative importance of each risk factor by comparing them in pairs. When one risk (risk i) is judged to be more significant than another (risk j), a numerical value representing this importance is assigned to the corresponding cell at row i, column j. Conversely, the reciprocal of this value is placed in the cell at row j, column i. An example of this comparison matrix is shown in Table 2.

- Calculation of the Consistency Ratio (CR)

- Calculate the sum of each column as shown in equation (1).

3.1.3. Fuzzy Operation

3.1.4. Ranking

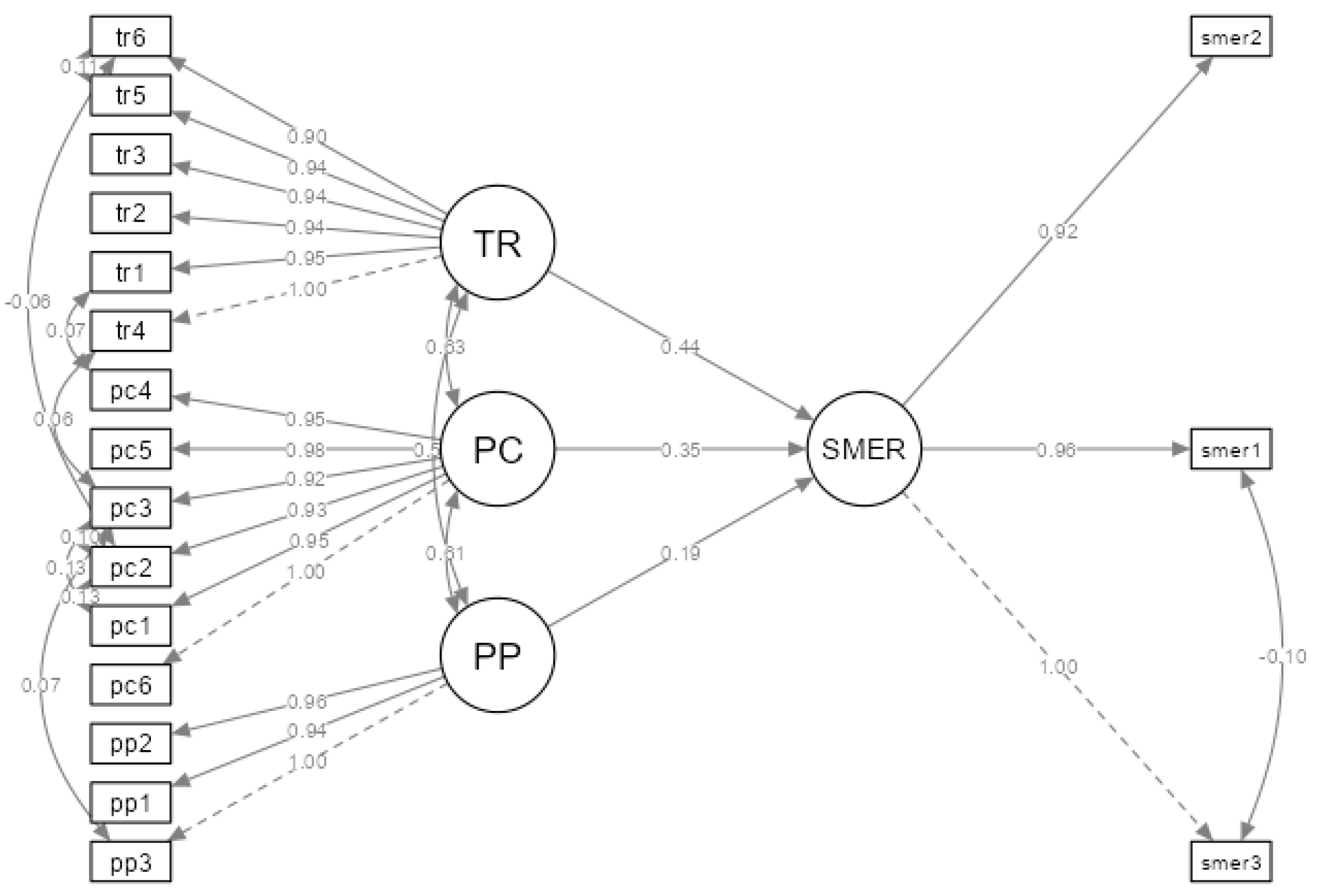

3.2. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

3.2.1. Population and Sample

3.2.2. Instrument

3.3. Indicator Development

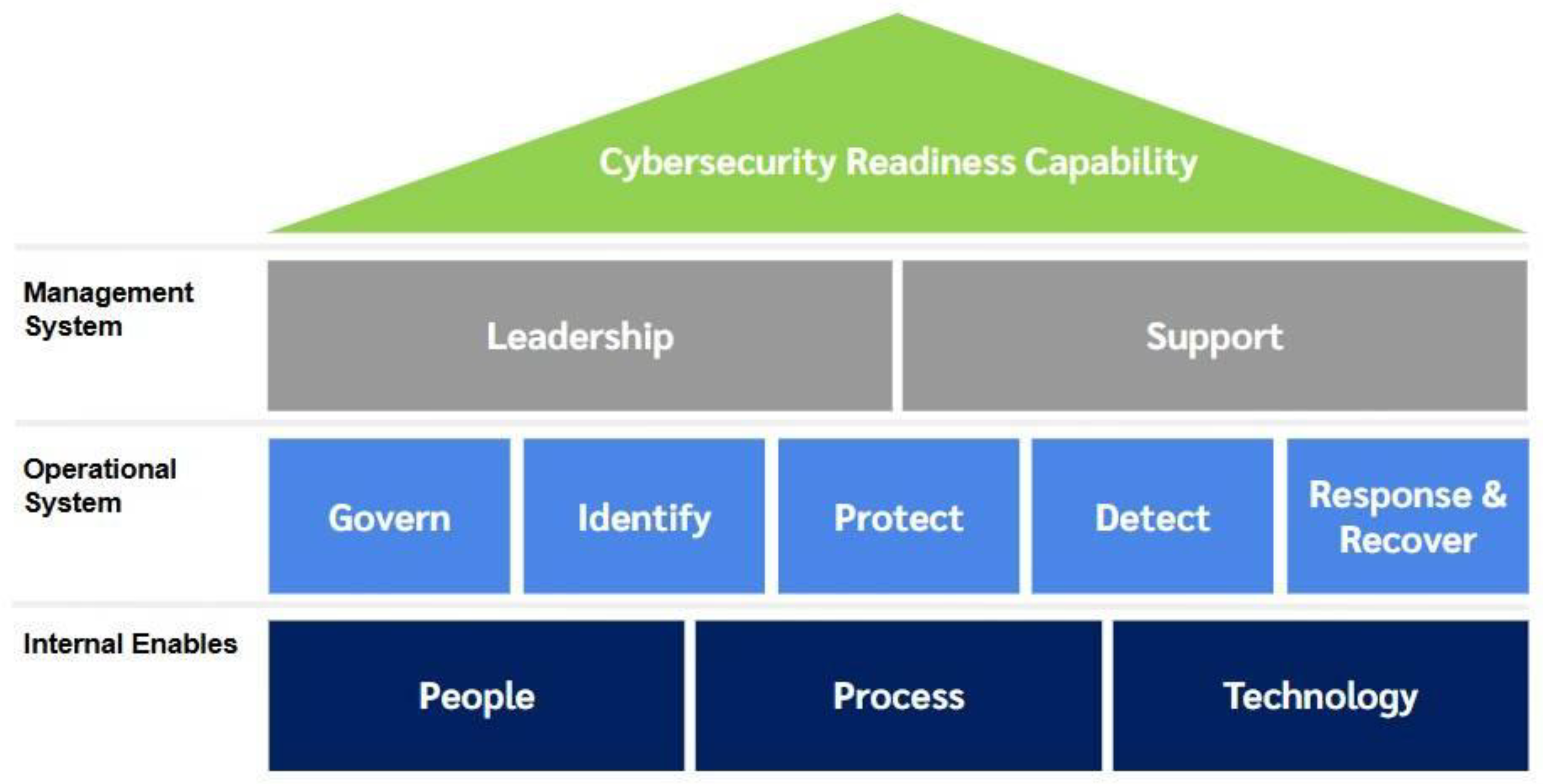

3.4. Development of the Capability Readiness Framework for Cybersecurity Protection

- Tier 1: Management System, aligned with ISO/IEC 27001:2022, targeting senior leadership and governance roles;

- Tier 2: Operational System, derived from the NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0, focusing on day-to-day cybersecurity operations and procedures;

- Tier 3: Internal Enablers, addressing the management of resources necessary to support readiness.

4. Results

4.1. Cybersecurity Risk Analysis Results

4.2. Results of the Analysis of Internal Factors Affecting SMEs’ Cybersecurity Readiness Capability

4.2.1. Validity and Reliability

4.2.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.3. Indicators of Cybersecurity Readiness Capability for SMEs

4.4. Framework for Developing Cybersecurity Readiness Capability for SMEs

4.4.1. Description of Framework Implementation

| Framework | Description |

|---|---|

| TIER 1: Management System | |

| Leadership | |

|

Senior management must demonstrate leadership and prioritize the implementation of the cybersecurity management system by establishing policies and objectives aligned with the SME’s strategic direction. They should integrate the system into various processes, allocate necessary resources, communicate the importance of the system, support personnel, promote continuous improvement, and encourage other managers to fulfill their respective roles. |

|

Senior management must ensure that clear roles, responsibilities, and authorities related to cybersecurity within the SME are defined and communicated. They should delegate these responsibilities to designated individuals who can ensure the system’s compliance with requirements and appropriately report the system’s performance to senior management. |

| Support | |

|

SMEs must allocate sufficient and appropriate resources to support the implementation, maintenance, and continuous improvement of the cybersecurity system to ensure effective and sustainable outcomes. |

|

SMEs must define, assess, and develop the competencies of personnel responsible for information security to ensure they possess appropriate knowledge, skills, or experience through continuous training and development, while maintaining documented evidence to verify competencies in accordance with requirements. |

|

SMEs must establish clear communication guidelines both internally and externally regarding the cybersecurity system, specifying what information will be communicated, when, by whom, and through which channels, to ensure understanding and effective implementation. |

|

SMEs must create, control, and maintain documented information related to the cybersecurity system to support operations and demonstrate compliance with requirements. This includes ensuring that the documentation is appropriate, comprehensive in detail, properly formatted, stored securely, approved, and accessible, as well as controlling against loss, alteration, or unauthorized use. |

| TIER 2: Operational System | |

| Govern | |

|

SMEs must understand the organization’s mission and use it as a guideline for managing cyber risks. They need to identify and comprehend the expectations of both internal and external stakeholders, including relevant legal requirements, and clearly communicate the SME’s context to these stakeholders. |

|

SMEs must establish a clear approach to cyber risk management by defining the objectives of risk management, setting the acceptable risk levels (Risk Appetite), and determining risk tolerance levels. These must be communicated effectively to employees and relevant stakeholders to ensure a shared understanding. Additionally, risk management activities should align with organizational policies and take into account the potential cyber impacts on business operations. |

|

The monitoring and evaluation of risk management and cybersecurity performance must be conducted regularly. The outcomes of risk management strategies should be communicated to relevant stakeholders and used to inform improvements in the organization’s strategies and direction, ensuring alignment with actual circumstances. Existing strategies must be continuously reviewed and developed. |

|

SMEs should establish clear guidelines for managing cybersecurity risks within the supply chain, especially concerning external service providers or partners. This includes defining roles and responsibilities, clearly communicating cybersecurity requirements, establishing agreements or contracts that comprehensively address security issues, continuously monitoring and evaluating partner performance, as well as developing response and recovery plans in the event of an incident. |

| Identify | |

|

SMEs should maintain a comprehensive asset inventory covering hardware, software, systems, data, services, and personnel related to business operations. This inventory must identify all assets relevant to cybersecurity risk management, be regularly updated, and categorize assets to facilitate access control and management. Additionally, the importance of each asset should be assessed to prioritize risks accordingly. |

|

SMEs should conduct systematic cybersecurity risk assessments to identify weaknesses or vulnerabilities in assets, personnel, and operational systems. They should regularly monitor cyber threat intelligence from reliable sources and evaluate potential impacts on both business operations and organizational reputation. Furthermore, emphasis should be placed on risk prioritization, response planning, thorough inspection of software and hardware to ensure no critical vulnerabilities exist, and assessment of third-party service providers. |

|

SMEs should establish guidelines for the continuous improvement of processes, workflows, and activities related to cybersecurity. This should be based on assessment results, user feedback, and lessons learned from past security incidents. Additionally, the outcomes of these improvements must be clearly communicated to all relevant stakeholders. |

| Protect | |

|

SMEs must define and control access to systems, data, and services, granting permissions only to authorized personnel or systems. This requires systematic user account management, assigning access rights based on roles and responsibilities, and enforcing multi-factor authentication to enhance security. Clear policies for access rights management should be established, periodic access reviews conducted, unauthorized access prevented, and permissions promptly revoked when no longer needed. |

|

SMEs must implement measures to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data, such as encryption, access control, and validation of data accuracy before use. Additionally, storage systems should be tested regularly to ensure they are operational when needed. Any data transferred outside the organization’s systems must be protected according to its level of sensitivity. |

|

SMEs must establish clear guidelines for managing the security of platforms, including hardware, software, operating systems, and applications. They should define and implement secure configuration practices and regularly maintain, update, and replace outdated equipment or software. Additionally, SMEs should retain log data to enable timely analysis of anomalous events and ensure that only licensed software is installed. |

|

SMEs should establish a flexible technology infrastructure that can continuously withstand threats or disruptions. Equipment, systems, and environments must be protected against unauthorized access. Additionally, preparedness for emergencies such as power outages, system failures, or natural disasters should be in place. This includes having backup resources or alternative solutions available for temporary use to enable rapid recovery and resumption of operations. |

| Detect | |

|

SMEs should have continuous monitoring and anomaly detection systems in all parts of their infrastructure, including networks, endpoints, environments, and user behaviors, to promptly identify indicators of compromise and enable rapid response actions. |

|

SMEs should have a systematic approach for analyzing cybersecurity incidents or anomalies. When a suspicious event or potential attack occurs, relevant data should be thoroughly collected and analyzed to identify the cause, origin, and impact of the incident, as well as to assess any connections with other threats. |

| Response & Recover | |

|

SMEs must develop a response plan for potential cybersecurity incidents, clearly specifying the response procedures, events that require notification, and responsible personnel. When an incident occurs, there should be systematic reporting, investigation, and response processes in place, including thorough management of evidence and assessment of the incident to prioritize its severity. |

|

SMEs should have a clear and actionable recovery plan to restore systems and services to normal operation following a cybersecurity incident. The recovery plan should clearly define roles and responsibilities, prioritize the assets that need to be recovered first, and include regular drills or tests to assess preparedness. |

| TIER 3: Internal Enablers | |

| People Readiness | |

|

SMEs must promote cybersecurity awareness among personnel at all levels by organizing training sessions or providing information about cyber threats. They should clearly communicate organizational policies and practices, regularly conduct educational activities or awareness campaigns, and continuously evaluate employees’ understanding. |

|

SMEs must promote continuous training and learning for personnel in cybersecurity, focusing on developing skills, knowledge, and competencies aligned with their roles. For example, technical training should be provided for IT staff, while security best practice training should be offered to general users. |

|

SMEs should promote research and development in cybersecurity by collaborating with research institutes, universities, or external organizations to exchange knowledge. This enables personnel to stay updated on new technologies, emerging threat trends, and modern prevention approaches, which can then be applied to their operations. |

| Process Readiness | |

|

The formulation of policies, strategies, and plans for cybersecurity must be clear. Policies should demonstrate the management’s commitment to protecting information and information systems. Strategies should align with the SME’s objectives, and plans must specify operational actions within defined timeframes, such as risk assessment, prevention, incident response, and system recovery. This ensures that cybersecurity efforts are purposeful and continuous. |

|

Cybersecurity assessments must be conducted regularly to measure the levels of risk, vulnerabilities, and the effectiveness of implemented measures. These assessments may include system testing (e.g., penetration testing), vulnerability analysis, compliance audits with policies or standards, and ongoing performance |

|

SMEs should establish a clear and systematic cybersecurity management framework that at minimum encompasses the approaches for prevention, detection, response, and recovery from cyber incidents. This framework should be based on international standards or best practices tailored to the specific characteristics of each SME, ensuring that cyber risk management is conducted in a structured manner, aligned with business operations, and practically implementable. |

|

SMEs should ensure effective coordination of cybersecurity efforts both within their organization and with relevant external agencies to enable a rapid and consistent response to threats. This coordination should include clearly defined roles and responsibilities, incident notification, joint incident management, and continuous communication of security-related information to strengthen defense systems and minimize risks arising from communication gaps. |

|

The improvement and development of the cybersecurity system must be carried out continuously, based on evaluation results, identified vulnerabilities, incidents that have occurred, and changes in technology or threats. These improvements should encompass policies, processes, technology, and personnel. |

| Technology Readiness | |

|

The allocation of tools, equipment, and technology used for cybersecurity must be sufficient in quantity and appropriate in quality, such as computers with antivirus software, backup systems, and monitoring tools. |

|

The devices, tools, and technologies used must be capable of responding rapidly to emerging threats. Utilizing modern and efficient technologies and equipment enhances the effectiveness of cybersecurity defenses and allows for future improvements as needed. |

|

SMEs must have measures in place to protect devices such as computers, servers, and network equipment by installing antivirus systems, firewalls, encryption software, and access controls. These measures help prevent attacks, data leaks, and unauthorized use, thereby reducing the risk of devices becoming vulnerabilities for cyber threats. |

|

SMEs should have systems and processes that support the rapid detection of cyber incidents or anomalies, along with a clear response plan when threats are identified. This is to limit the impact, restore operations, and prevent recurrence. |

|

Digital devices and tools must have their software and operating systems regularly updated to close security vulnerabilities that could be exploited by cyber threats. Updates should be continuous and up-to-date for both core systems and supporting programs to ensure that all devices remain secure and function efficiently. |

|

SMEs must allocate secure and appropriate devices and systems that personnel can access conveniently, both during normal operations and in the event of a security threat. Access controls should be in place, such as secure authentication and permission settings, to prevent unauthorized access to data or systems. |

|

SMEs must have appropriate infrastructure to support cybersecurity, such as secure network systems, intrusion prevention systems, data backup, and secure data storage. This infrastructure should effectively support threat prevention, incident detection, and system recovery. |

4.4.2. Evaluation Results of the Capability Development Framework for Cybersecurity Readiness for SMEs

5. Conclusions

References

- Neri, M.; Niccolini, F.; Pugliese, R. Assessing SMEs’ Cybersecurity Organizational Readiness: Findings from an Italian Survey. Open J. Adv. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perozzo, H.; Zaghloul, F.; Ravarini, A. CyberSecurity Readiness: A Model for SMEs Based on the Socio-Technical Perspective. Complex Syst. Inform. Model. Q. 2022, 33, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szedlak, C.; Reinemann, H.; Hatzelmann, S. Ensuring Cybersecurity Compliance: Assessing SME Awareness and Preparedness for the Cyber Resilience Act. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management; IEOM Society International, Tokyo, Japan, 10 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laarhoven, P.J.M.; Pedrycz, W. A Fuzzy Extension of Saaty’s Priority Theory. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1983, 11, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization; International Electrotechnical Commission. ISO/IEC 27001:2022—Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements; ISO/IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyabe, M.F.; Arranz, C.F.A.; Fernandez De Arroyabe, I.; Fernandez De Arroyabe, J.C. Exploring the Economic Role of Cybersecurity in SMEs: A Case Study of the UK. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanda, S.; Tanner, M.; Kent, C. Exploring SME Cybersecurity Practices in Developing Countries. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2018, 28, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Hinteregger, C.; Zieba, M. The Effect of Environmental Turbulence on Cyber Security Risk Management and Organizational Resilience. Comput. Secur. 2024, 137, 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, C.R.; Becker, I.; Johnson, S. Unaware, Unfunded and Uneducated: A Systematic Review of SME Cybersecurity. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.17186. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.17186 (accessed on 18 June 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). Risk Assessment in Practice; COSO: Durham, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO); International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). ISO/IEC 27005:2018—Information Technology—Security Techniques—Information Security Risk Management; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. A Scaling Method for Priorities in Hierarchical Structures. J. Math. Psychol. 1977, 15, 234–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.-Y. Applications of the Extent Analysis Method on Fuzzy AHP. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1996, 95, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.J. Fuzzy Hierarchical Analysis. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1985, 17, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, A.; Neo, L.S.; Goh, P.; Lee, S.; Khader, M.; Ong, G.; Chin, J. Cyber Hygiene: The Concept, Its Measure, and Its Initial Tests. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 128, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, W.D.; Kruger, H.A. Can Perceptual Differences Account for Enigmatic Information Security Behaviour in an Organisation? Comput. Secur. 2016, 61, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.; McCormac, A.; Butavicius, M.; Pattinson, M.; Jerram, C. Determining Employee Awareness Using the Human Aspects of Information Security Questionnaire (HAIS-Q). Comput. Secur. 2014, 42, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldabbas, H.; Oberholzer, N. The Influence of Transformational and Learning through R&D Capabilities on the Competitive Advantage of Firms. Arab Gulf J. Sci. Res. 2024, 42, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Makridis, C.A.; Smeets, M. Determinants of Cyber Readiness. J. Cyber Policy 2019, 4, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Ali, M.; Kurnia, S.; Thurasamy, R. Evaluating the Cyber Security Readiness of Organizations and Its Influence on Performance. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 58, 102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, A.; Çağlar, D.; Zoubi, K. The Impact of Production and Operations Management Practices in Improving Organizational Performance: The Mediating Role of Supply Chain Integration. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Yadav, U.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, K. Enhancing Cyber Resilience through Synergistic Cybersecurity and Cyber Defence Strategies. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Cutting-Edge Developments in Engineering Technology and Science (ICCDETS 2024), India; 2024; pp. 862–866. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Manzano, J.A.; San Feliu, T.; Herranz, Á.; Mariño, J.; Fredlund, L.-Å.; Colomo-Palacios, R.; Moreno, A.M. Towards an Integrated Cybersecurity Framework for Small and Medium Enterprises. In Systems, Software and Services Process Improvement; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 2179, pp. 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Syed, A.A.; Shaikh, M.Z. A Two-Decade Literature Review on Challenges Faced by SMEs in Technology Adoption. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2021, 25, 3. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3823849 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Saad, S.M.; Bahadori, R.; Jafarnejad, H. The Smart SME Technology Readiness Assessment Methodology in the Context of Industry 4.0. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 32, 1037–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukimin, R.; Mahmood, W.H.W.; Nordin, M.M. Application of Fuzzy AHP for Supplier Development Prioritization. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2022, 9, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision Making with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. 2008, 1, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781483377445. [Google Scholar]

- Berlilana, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Noparumpa, T.; Ruangkanjanases, A.; Hariguna, T. Sarmini Organization Benefit as an Outcome of Organizational Security Adoption: The Role of Cyber Security Readiness and Technology Readiness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; Niccolini, F.; Martino, L. Organizational Cybersecurity Readiness in the ICT Sector: A Quanti-Qualitative Assessment. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2024, 32, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badi, S.; Nasaj, M. Cybersecurity Effectiveness in UK Construction Firms: An Extended McKinsey 7S Model Approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 4482–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweheyo, G.; Abaho, E.; Verma, A.M.; Musenze, I. The Mediating Role of Transformational Leadership in the Relationship Between Institutional Pressures and Collaboration with Commercialization of University Research Output: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2024, 21, 2450008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781462523351. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom, J.T. Some Clarifications and Recommendations on Fit Indices. USP 2012, 655, 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, F.; Gatzert, N.; Gruner, P. Cyber Risk Management in SMEs: Insights from Industry Surveys. J. Risk Finance 2021, 22, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustiarini, N.W.; Bhegawati, D.A.S.; Mendra, N.P.Y.; Vipriyanti, N.U. Resource Orchestration in Enhancing Green Innovation and Environmental Performance in SME. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2023, 13, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chege, S.M.; Wang, D. The Influence of Technology Innovation on SME Performance through Environmental Sustainability Practices in Kenya. Technology in Society 2020, 60, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Vergara, M.; García-Pérez-de-Lema, D. Product Innovation and Performance in SME’s: The Role of the Creative Process and Risk Taking. Innovation 2021, 23, 470–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe-Walsh, L.; Kirk, S.; Oruh, E. Are People the Greatest Asset: Talent Management in SME Hotels in Nigeria during the COVID-19 Crisis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 2708–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartamorn, S.; Oe, H. Cyberspace Communication in the SME Business Context: Exploring Ways to Improve Technological Readiness and Capability of Thai SMEs. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME); IEEE: Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain, 19 July, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadian, H.D.; Alijani, O.; Moghadam, M.R.; Ameri, B. Navigating the Future by Fuzzy AHP Method: Enhancing Global Tech-Sustainable Governance, Digital Resilience, & Cybersecurity via the SME 5.0, 7PS Framework & the X.0 Wave/Age Theory in the Digital Age. AIMS Geosci. 2024, 10, 371–398. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan, G.; Thamrongthanakit, T. Cybersecurity Management Practices in Thai SMEs. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth Midwest Association for Information Systems Conference (MWAIS 2024), Peoria, IL, USA, 16–17 May 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haastrecht, M.; Sarhan, I.; Shojaifar, A.; Baumgartner, L.; Mallouli, W.; Spruit, M. A Threat-Based Cybersecurity Risk Assessment Approach Addressing SME Needs. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES 2021), Vienna, Austria, 17 August 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ajmi, L.; Hadeel; Alqahtani, N.; Ur Rahman, A.; Mahmud, M. A Novel Cybersecurity Framework for Countermeasure of SME’s in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Computer Applications & Information Security (ICCAIS), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, May 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–9.

| Intensity of Importance | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Equal importance |

| 3 | Moderate importance |

| 5 | Strong importance |

| 7 | Demonstrated important |

| 9 | Extreme importance |

| 2,4,6,8 | Intermediate values between two adjacent judgments |

| RISK | …. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 7 | |

| 1/5 | 1 | 3 | |

| …. | 1/7 | 1/3 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.89 | 1.12 | 1.26 | 1.36 | 1.41 | 1.46 | 1.49 |

| Level of Importance | TFNs | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (1,1,1) | Equally important |

| 3 | (1,3,5) | Little less important |

| 5 | (3,5,7) | More important |

| 7 | (5,7,9) | Much more important |

| 9 | (7,9,9) | Maximum important |

| Factor | Finance | Operation | Monitoring | People | Reputation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance | 1.0 | 1.6022 | 2.5822 | 2.0473 | 2.8300 |

| Operation | 1.6466 | 1.0 | 2.1022 | 2.0906 | 2.8928 |

| Monitoring | 1.2400 | 1.0188 | 1.0 | 1.5062 | 1.9967 |

| People | 2.1372 | 2.4101 | 2.1711 | 1.0 | 2.8667 |

| Reputation | 1.4463 | 1.6309 | 1.7806 | 0.4455 | 1.0 |

| Factor | Finance | Operation | Monitoring | People | Reputation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Operation | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Monitoring | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| People | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Reputation | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Value in Metrix | TFNs (Lower, Middle, Upper) |

|---|---|

| 1 | (1, 1, 1) |

| 3 | (1, 3, 5) |

| 5 | (3, 5, 7) |

| 7 | (5, 7, 9) |

| 9 | (7, 9, 9) |

| Factor | Finance | Operation | Monitoring | People | Reputation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 3, 5) | (3, 5, 7) | (1, 3, 5) | (3, 5, 7) |

| Operation | (1, 3, 5) | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 3, 5) | (1, 3, 5) | (3, 5, 7) |

| Monitoring | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 3, 5) | (1, 3, 5) |

| People | (1, 3, 5) | (1, 3, 5) | (1, 3, 5) | (1, 1, 1) | (3, 5, 7) |

| Reputation | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 3, 5) | (1, 3, 5) | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1, 1) |

| Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Finance | 5 | 9 | 13 |

| Operation | 5 | 11 | 17 |

| Monitoring | 7 | 15 | 23 |

| People | 5 | 11 | 17 |

| Reputation | 11 | 19 | 27 |

| Factor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance | 0.0769, 0.1111, 0.2 |

0.0588, 0.2727, 1 |

0.1304, 0.3333, 1 |

0.0588, 0.2727, 1 |

0.1111, 0.2632, 0.6364 |

| Operation | 0.0769, 0.3333, 1 |

0.0588, 0.0909, 0.2 |

0.0435, 0.2, 0.7143 |

0.0588, 0.2727, 1 |

0.1111, 0.2632, 0.6364 |

| Monitoring | 0.0769, 0.1111, 0.2 |

0.0588, 0.0909, 0.2 |

0.0435, 0.0667, 0.1429 | 0.0588, 0.2727, 1 |

0.0370, 0.1579, 0.4545 |

| People | 0.0769, 0.3333, 1 |

0.0588, 0.2727, 1 |

0.0435, 0.2, 0.7143 |

0.0588, 0.0909, 0.2 |

0.1111, 0.2632, 0.6364 |

| Reputation | 0.0769, 0.1111, 0.2 |

0.0588, 0.2727, 1 |

0.0435, 0.2, 0.7143 |

0.0588, 0.0909, 0.2 |

0.0370, 0.0526, 0.0909 |

| Factor | |||

| Finance | 0.0872 | 0.2506 | 0.7673 |

| Operation | 0.0698 | 0.2320 | 0.7101 |

| Monitoring | 0.0550 | 0.1399 | 0.3995 |

| People | 0.0698 | 0.2320 | 0.7101 |

| Reputation | 0.0550 | 0.1455 | 0.4410 |

| Factor | Defuzzified Weight |

|---|---|

| Finance | 0.3684 |

| Operation | 0.3373 |

| Monitoring | 0.1981 |

| People | 0.3373 |

| Reputation | 0.2138 |

| Order of Importance | Factor | Defuzzified Weight |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Finance | 0.3684 |

| 2 | Operation | 0.3373 |

| 2 | Personnel | 0.3373 |

| 4 | Reputation | 0.2138 |

| 5 | Monitoring | 0.1981 |

| Factors | Items | Loadings | AVE | CR | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thresholds | > 0.7 | > 0.5 | > 0.7 | > 0.7 | |

| People Readiness (PP) | .668 | .858 | .858 | ||

| PP1 | .785 | ||||

| PP2 | .812 | ||||

| PP3 | .854 | ||||

| Process Readiness (PC) | .673 | .925 | .931 | ||

| PC1 | .814 | ||||

| PC2 | .794 | ||||

| PC3 | .801 | ||||

| PC4 | .819 | ||||

| PC5 | .841 | ||||

| PC6 | .853 | ||||

| Technology Readiness (TR) | .719 | .939 | .942 | ||

| TR1 | .852 | ||||

| TR2 | .844 | ||||

| TR3 | .843 | ||||

| TR4 | .891 | ||||

| TR5 | .842 | ||||

| TR6 | .813 | ||||

| SME’s Cybersecurity Readiness (SMER) | .672 | .860 | .852 | ||

| SMER | .812 | ||||

| SMER | .773 | ||||

| SMER | .872 | ||||

| PP | PC | TR | SMER | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTMT | ||||

| PP | ||||

| PC | .857 | |||

| TR | .711 | .782 | ||

| SMER | .852 | .871 | .802 | |

| Fornell-Larcker criterion | ||||

| PP | .817 | |||

| PC | .767 | .821 | ||

| TR | .642 | .737 | .848 | |

| SMER | .726 | .775 | .705 | .820 |

| X2 | df | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model tests | |||

| User model | 355 | 120 | <.001 |

| Baseline model | 5246 | 153 | <.001 |

| Fit indices | |||

| CFI | 0.954 | NFI | 0.932 |

| TLI | 0.941 | RFI | 0.914 |

| NNFI | 0.941 | IFI | 0.954 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Estimate | β | z | p | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PP -> SMER | 0.185 | 0.183 | 2.35 | 0.019 | Support |

| H2 | PC -> SMER | 0.351 | 0.354 | 3.91 | <.001 | Support |

| H3 | TR -> SMER | 0.438 | 0.554 | 7.39 | <.001 | Support |

| 95% Confidence Intervals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent | Observed | β | Lower | Upper | z | p |

| PP | pp3 | 0.846 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| pp1 | 0.787 | 0.821 | 1.052 | 15.9 | <.001 | |

| pp2 | 0.807 | 0.846 | 1.075 | 16.5 | <.001 | |

| PC | pc6 | 0.857 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| pc1 | 0.812 | 0.843 | 1.051 | 17.9 | <.001 | |

| pc2 | 0.797 | 0.827 | 1.037 | 17.4 | <.001 | |

| pc3 | 0.792 | 0.816 | 1.026 | 17.2 | <.001 | |

| pc5 | 0.842 | 0.882 | 1.083 | 19.1 | <.001 | |

| pc4 | 0.816 | 0.851 | 1.057 | 18.2 | <.001 | |

| TR | tr4 | 0.893 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 22.2 | |

| tr1 | 0.864 | 0.865 | 1.032 | 20.9 | <.001 | |

| tr2 | 0.841 | 0.849 | 1.025 | 21.1 | <.001 | |

| tr3 | 0.845 | 0.854 | 1.029 | 20.9 | <.001 | |

| tr5 | 0.843 | 0.851 | 1.027 | 19.5 | <.001 | |

| tr6 | 0.814 | 0.807 | 0.987 | <.001 | ||

| SMER | smer3 | 0.849 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| smer1 | 0.818 | 0.840 | 1.086 | 15.3 | <.001 | |

| smer2 | 0.784 | 0.811 | 1.034 | 16.2 | <.001 | |

| Item | Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Factor 1: People Readiness | ||||

| 1. | SME: Promotes raising cybersecurity awareness among their personnel. | 0.545 | ||

| 2. | SME: Encourages personnel to undergo training in internationally recognized cybersecurity courses. | 0.741 | ||

| 3. | SME: There is research and development in cybersecurity within organizations and network agencies. | 0.631 | ||

| Factor 2: Process Readiness | ||||

| 1. | SME There are strategies, policies, and planning related to cybersecurity. | 0.728 | ||

| 2. | SMEs continuous monitoring and evaluation of cybersecurity operations. | 0.806 | ||

| 3. | SMEs utilize internationally standardized cybersecurity frameworks as the foundation for their cybersecurity operations. | 0.718 | ||

| 4. | SMEs seek collaboration with external agencies to develop, enhance, and strengthen their cybersecurity capabilities. | 0.664 | ||

| 5. | SMEs have continuously developed and improved their cybersecurity measures. | 0.693 | ||

| Factor 3: Technology Readiness | ||||

| 1. | SMEs have sufficient cybersecurity technology in terms of both quantity and quality. | 0.780 | ||

| 2. | SMEs use modern and effective cybersecurity technologies. | 0.690 | ||

| 3. | Most of the equipment used by SMEs is installed with cybersecurity software (such as antivirus or malware protection programs). | 0.763 | ||

| 4. | SMEs possess cybersecurity technologies capable of rapidly and accurately detecting and responding to cyber threats. | 0.761 | ||

| 5. | The tools, equipment, and technologies of SMEs are regularly updated. | 0.825 | ||

| 6 | SME personnel have access to tools and equipment that can support operations when encountering cyber threats or attacks. | 0.788 | ||

| 7. | SMEs have sufficiently quality management processes for critical cybersecurity infrastructure systems. | 0.589 | ||

| Questions | Assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Suitability of the Capability Development Framework for Cybersecurity Readiness for SMEs | 4.50 | The most |

| 2. | Acceptance of the Capability Development Framework for Cybersecurity Readiness for SMEs | 4.67 | The most |

| 3. | Feasibility of Implementing the Capability Development Framework for Cybersecurity Readiness for SMEs | 4.17 | Very much |

| The sum of average | 4.44 | The most | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).