1. Introduction

In HIV/HBV co-infection, although the implementation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) effectively suppresses HIV replication and concurrently inhibits HBV replication, complete elimination of intrahepatic covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) remains challenging. As a result, residual HBV transcription and translation in hepatocytes may persist despite antiviral therapy [

1,

2], ultimately leading to enhanced hepatic inflammatory responses and accelerating the progression of liver disease [

3,

4]. Among individuals with HIV/HBV co-infection, liver-related mortality ranks second only to AIDS-related mortality following long-term ART, with 83% of liver-related deaths attributable to viral hepatitis [

5].

Previous studies have reported that point mutations and deletion mutations within the HBV PreS region are associated with aggravated liver disease in HBV mono-infection, and have been identified as independent risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Notably, patients harboring PreS deletions exhibit a higher incidence of end-stage liver disease [

6,

8]. Our research group has previously found that people co-infected with HIV and HBV harbor a high proportion of PreS deletion mutantions within the viral quasispecies population [

12]. However, the long-term hepatic outcomes in people co-infected with HIV and HBV carrying a high proportion of PreS point mutations and deletions under sustained antiviral therapy remain inadequately characterized.

Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the impact of PreS deletion mutations on long-term liver prognosis in people co-infected with HIV and HBV. This will be achieved through a comprehensive analysis of clinical data, laboratory parameters, and PreS region clonal sequencing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort

Among the HIV clinical cohort in Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital (No. 20180307),435 people living with HIV and HBV co-infection with initial anti-virus treatment between 2009 to 2019 were recruited, with excluded criteria at treatment baseline as follows: (1) HBV DNA < 1000IU/L in plasma; (2) individuals with cancer or end-stage liver disease (ESLD); (3) individuals co-infected with other types of hepatitis virus (such as HAV, HCV, HDV) and/or other apparent opportunistic infections; (4) individuals with age <18 years or >65 years, (5) pregnant or lactating women; (6) individuals with cardiovascular disease or renal failure, (7)No available plasma samples at baseline, (8) PCR and/or sequencing of the HBV PreS region was unsuccessful. Based on the presence of HCC-associated point mutations in the PreS region (G2950A, G2951A, A2962G, and C2964A), cases were classified into the point mutation group (PM) and the non-point mutation group (Non-PM). According to the location of deletion mutations, cases were further categorized as PreS1 region deletion (PreS1 del), PreS2 region deletion (PreS2 del), deletions in both PreS1 and PreS2 regions (PreS1+2 del), and without deletion in the PreS region (w/o del). The study protocol conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Eighth People's Hospital (Ethics Approval: 202033166). Written informed consent was obtained from individuals.

2.2. Clinical Data Collection and Serological Examination

Demographic, clinical characteristics and laboratory data were collected from the clinical cohort.

2.3. Analysis of HBV PreS Region with T-A Cloning and Sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from a 200 μL serum sample collected from each patient using a fully automated nucleic acid extractor (Smart 32 Daan Genetics), with kit No. DA0623. The primers for the first round of nested PCR were 5ʹ-GCCTCATTTTGYGGGTCACCATATTC-3ʹ and 5'-CTGTTCCKGAACTGGAGCCACC-3'. The primers for the second round of nested PCR were 5ʹ-GGGTCACCATATTCTTGGGAACAAGA-3ʹ and 5'-CTGTTCCKGAACTGGAGCCACC-3'. The first round of PCR amplification was performed in a 25 μL reaction system using 4 μL of DNA template (DNA extracted from serum). The amplification conditions (20 cycles) of the first round were as follows: denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 56°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. The second round of PCR amplification was performed in a 50 μL reaction system using 3 μL of DNA template. The amplification conditions (35 cycles) of the second round were as follows: denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 56°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. The purified product was ligated into a pMD19-T vector and transformed into JM109 cells. 50-60 clones were selected and sequenced. PreS regions were aligned with the reference sequences (genotype C2, GenBank accession no. AB014378 and genotype C2, GenBank accession no. AB048705) using Bioedit (V.7.0) software. All mutations were checked manually. PreS1 region, nt 2848– 3204; PreS2 region, nt 3205–154. HCC-associated point mutations: G2950A, G2951A, A2962G, and C2964A

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 25.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA), and graphs were produced using GraphPad Prism 9.5 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Continuous variables are described as the median (interquartile range [IQR]). Categorical variables are described by the frequency (percentage [%]). Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. All of the statistical tests were two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Result

3.1. Baseline Clinical Characteristics of People Living with HIV and HBV Co-Infection with HCC-Associated Point Mutations or Different Deletion Mutations in the PreS Region

A total of 435 people living with HIV and HBV co-infection were included in this study. The median age was 40 years (IQR: 33.5-50), with 376 participants (86.4%) being male. Regarding transmission routes, 197 patients (45.3%) were infected through men who have sex with men (MSM), 198 (45.5%) through heterosexual transmission (HST), 7 (1.6%) through injection drug use (IDU), and 33 (7.6%) had unknown transmission routes (

Table 1).

Among the 435 cases, 317 (72.9%) had HCC-associated point mutations (PM), and 118 (27.1%) had no point mutations (Non-PM). PM exhibited significantly different characteristics compared to Non-PM: the male sex was more prevalent in PM (

p = 0.027). HBV genotype C was significantly less frequent in PM (

p<0.001). HBV DNA levels were significantly lower in PM (median 7.62 vs 8.06 Log10 IU/L,

p=0.005). HBsAg levels were significantly higher in PM (median 2815 vs 1504 COI,

p<0.001). HBeAg levels were significantly lower in PM (median 72.37 vs 1123.5 COI,

p<0.001), with HBeAg positivity also being significantly lower (

p<0.001). Conversely, HBeAb levels were significantly lower in PM (median 1.3 vs 4.72 COI,

p<0.001), and HBeAb positivity was significantly higher in PM (

p=0.001). As for liver function indicators, no significant differences were observed (

Table 1).

PreS deletion mutations were identified in 95 patients (21.8%), with 46 patients (10.6%) having PreS1 deletions(PreS1 del), 22 (5.1%) having PreS2 deletions(PreS2 del), 27 (6.2%) having PreS1 and PreS2 deletions(PreS1+2 del), and 340 (78.2%) having no deletions(w/o del). Patients with different deletion patterns showed significant age differences (

p=0.014), PreS2 del group being older (median age 50 years). HBV genotype C distribution varied significantly across deletion groups (

p<0.001). HBV DNA levels differed significantly between groups (

p=0.006), PreS2 del group showing the lowest levels (median 6.62 Log10 IU/L). HBsAg levels were significantly different across groups (

p<0.001), being highest in the PreS1+2 del group (median 6915 COI). HBeAg levels and positivity rates were the lowest in the PreS2 del group, varied significantly among deletion groups (

p=0.015 and

p<0.001). HBeAb levels and positivity rates also showed significant differences (

p=0.009 and

p<0.001). No significant differences were observed in HBsAb positivity, HBcAb positivity (

Table 2).

Liver function parameters demonstrated significant associations with deletion mutations (Table2). AFP levels were significantly elevated in patients with deletions (p<0.001), PreS1+2 del group showing the highest levels (median 7.19 μg/L). ALT and AST levels were significantly higher in deletion groups (p=0.039 and p<0.001), PreS1+2 del group showing the highest values. Total bilirubin was highest in the PreS2 del group (median 12.18 μmol/L), and the difference was statistically significant (p=0.020). Platelet counts were significantly lower in deletion groups (p=0.014), particularly in PreS2 deletion patients (median 124×10^9/L). Liver fibrosis markers APRI and FIB-4 were significantly elevated in deletion groups (both p<0.001), with PreS2 deletion patients showing the highest values (median APRI 1.06, median FIB-4 3.15).

3.2. HCC-Associated Point Mutations Had No Significant Impact on Liver Function Prognosis in People Living with HIV and HBV Co-Infection

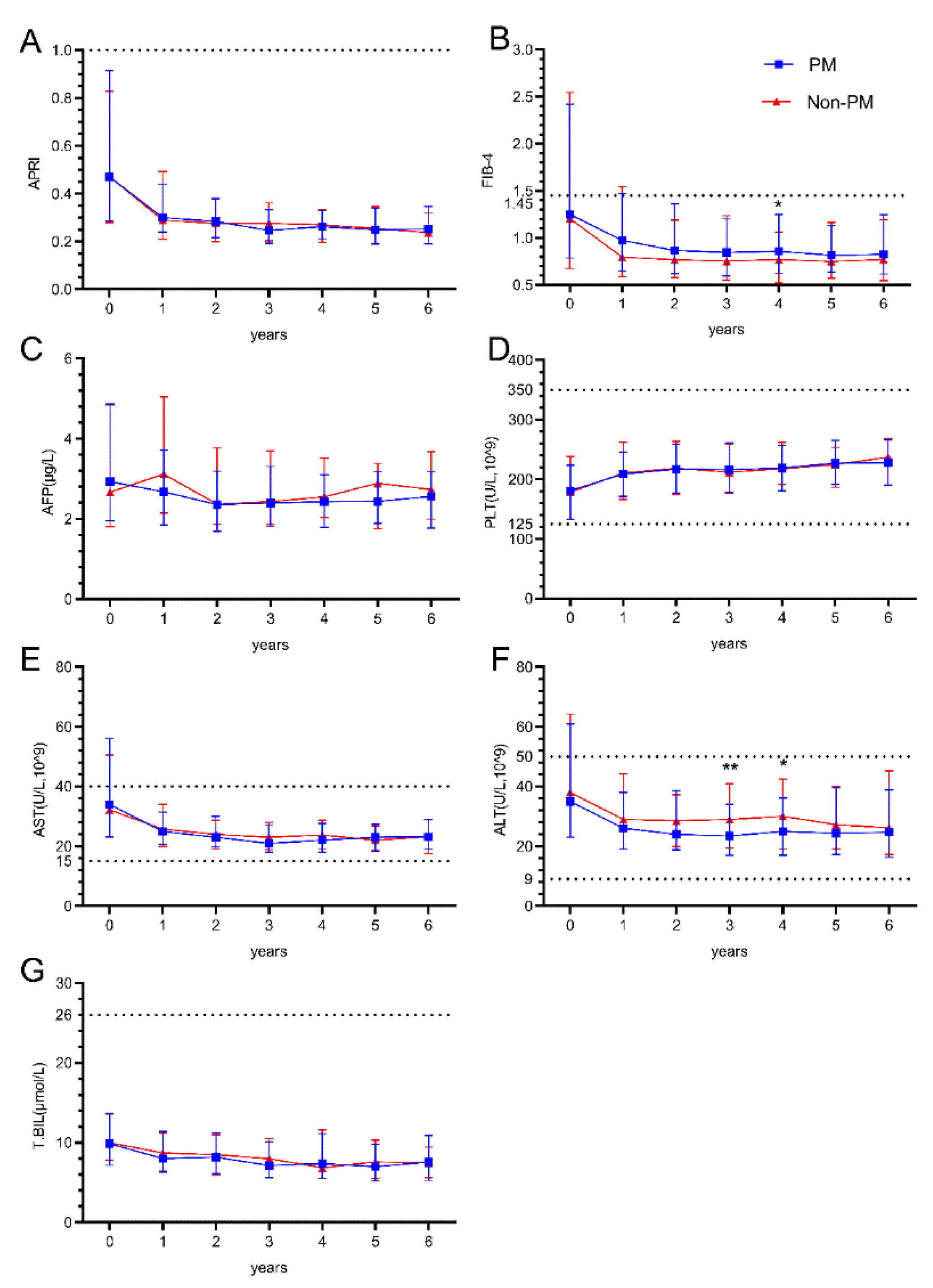

During the 6-year follow-up period after ART initiation, hepatic parameters showed distinct patterns between PM and Non-PM group. APRI values demonstrated a sharp decline from baseline to year 1 in both groups, then remained stable throughout the follow-up period with no significant differences between groups (Figure1A). FIB-4 values showed a similar pattern of initial decline and stabilization, with a significant difference observed at year 4 (p=0.042), where the non-PM group maintained slightly lower values (Figure1B).

ALT levels showed significant differences at years 3 and 4 (p=0.009 and p=0.036). Both groups demonstrated a decline from baseline values (median 35 and 38 U/L) to lower levels (median 26 and 29 U/L) by year 1, which were maintained throughout follow-up (Figure1F). AST levels followed similar trajectories with initial decline from baseline and stabilization at lower levels, without significant between-group differences (Figure1E). Total bilirubin levels remained stable around 8-10 μmol/L throughout the follow-up period in both groups (Figure1G). AFP levels showed slight fluctuations but remained within the range of 2.5-3.0 μg/L across all time points without significant differences (Figure1C). Platelet counts demonstrated a gradual increase from baseline values (median 181 and 178×10^9/L) to higher levels (median 228 and 237×10^9/L) by year 6 in both groups (Figure1D).

Figure 1.

The impact of HBV PreS point mutations on Hepatic outcomes in People living with HIV and HBV co-infection. (A.B) Longitudinal changes in liver fibrosis and cirrhosis risk scores (APRI/FIB-4) over six years after treatment; (C~G) Longitudinal changes in liver function Indicators (AFP, PLT, AST, ALT, T.BIL) over six years after treatment; The Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups. p < 0.05 represents the difference is statistically significant. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ,***p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

The impact of HBV PreS point mutations on Hepatic outcomes in People living with HIV and HBV co-infection. (A.B) Longitudinal changes in liver fibrosis and cirrhosis risk scores (APRI/FIB-4) over six years after treatment; (C~G) Longitudinal changes in liver function Indicators (AFP, PLT, AST, ALT, T.BIL) over six years after treatment; The Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups. p < 0.05 represents the difference is statistically significant. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ,***p < 0.001.

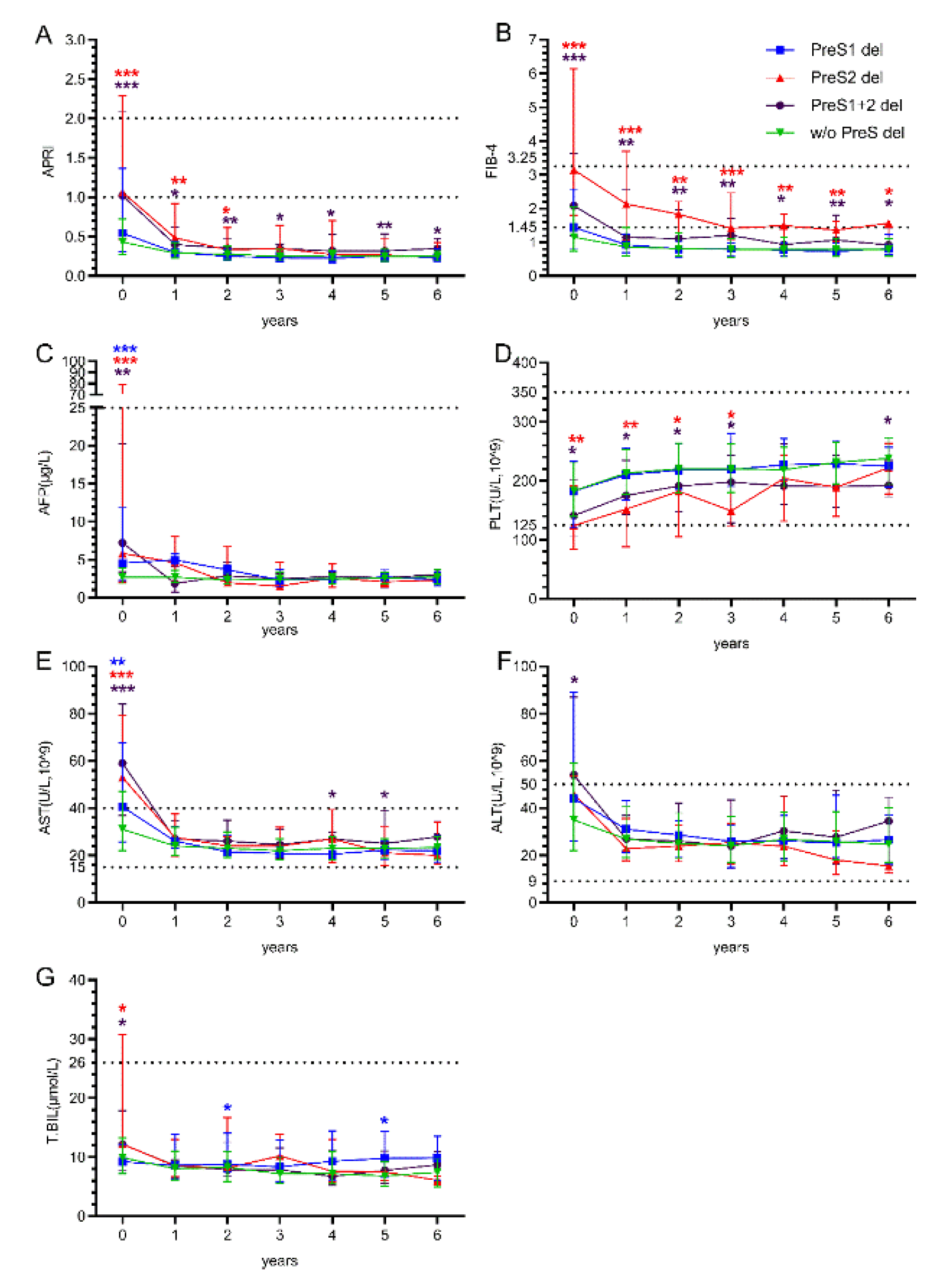

3.3. Deletion Mutations in the PreS2 Region Exacerbate the Risk of Liver Fibrosis and Cirrhosis in People Living with HIV and HBV Co-Infection

Patients with different PreS deletion patterns showed markedly distinct long-term outcomes. APRI values at baseline were significantly elevated in PreS2 del group (median 1.06,IQR 0.5-2.09) and PreS1+2 del group (median 1.02,IQR 0.6-1.5) compared to w/o del group (Below the risk range). Significant differences persisted at years 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, the PreS1+2 del group consistently showing the highest values throughout follow-up (Figure2A). FIB-4 values demonstrated the most pronounced differences, PreS2 and PreS1+2 del group showing markedly elevated baseline values (median 3.15, almost reached the high-risk range) compared to w/o del group. Significant differences were maintained at years 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, PreS2 del group consistently exhibiting the highest values throughout the follow-up period (Figure2B). Although AFP levels were significantly higher in the deletion groups at baseline, they remained consistently below 25 during the treatment period (Figure2C). Platelet counts showed initial recovery patterns across all groups, with values increasing from baseline to the reference value range by year 6, but PreS2 and PreS1+2 deletion groups remained significantly lower at baseline and during years 1 to 3 of treatment without significant between-group differences during 4-6 year (Figure2D).

AST levels demonstrated significant baseline differences among deletion groups, with PreS2 deletion patients showing the highest values. All groups showed improvement over time, with convergence toward normal ranges by year 1-6(Figure2E). ALT levels showed less pronounced differences among deletion groups during follow-up, with all groups maintaining relatively stable values after the initial year (Figure2F). Total bilirubin levels remained stable across all deletion groups throughout the 6-year follow-up period, A significant increase was observed in the PreS1 del group in the second and fifth years of treatment (Figure2G).

Figure 2.

The impact of HBV PreS deletions mutations on Hepatic outcomes in People living with HIV and HBV co-infection. (A.B) Longitudinal changes in liver fibrosis and cirrhosis risk scores (APRI/FIB-4) over six years after treatment; (C~G) Longitudinal changes in liver function Indicators (AFP, PLT, AST, ALT, T.BIL) over six years after treatment; The Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups. p < 0.05 represents the difference is statistically significant. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ,***p < 0.001. Blue asterisks indicate the comparison between "PreS1 del" and "w/o del"; Red asterisks indicate the comparison between "PreS2 del" and "w/o del"; Purple asterisks indicate the comparison between "PreS1+2 del" and "w/o del".

Figure 2.

The impact of HBV PreS deletions mutations on Hepatic outcomes in People living with HIV and HBV co-infection. (A.B) Longitudinal changes in liver fibrosis and cirrhosis risk scores (APRI/FIB-4) over six years after treatment; (C~G) Longitudinal changes in liver function Indicators (AFP, PLT, AST, ALT, T.BIL) over six years after treatment; The Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups. p < 0.05 represents the difference is statistically significant. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ,***p < 0.001. Blue asterisks indicate the comparison between "PreS1 del" and "w/o del"; Red asterisks indicate the comparison between "PreS2 del" and "w/o del"; Purple asterisks indicate the comparison between "PreS1+2 del" and "w/o del".

4. Discussion

Our study included 435 individuals co-infected with HIV and HBV and found that the prevalence of HCC-associated point mutations was 72.9%. These point mutations were predominantly of HBV genotype B (84.5%), which differs from previous findings in HBV mono-infected individuals, where genotype C–related mutations were more common [

7].We found that the point mutations reduced HBV DNA and HBeAg levels, and showed higher HBsAg and HBeAb positivity. However, some studies have indicated that point mutations do not result in significant changes in HBV DNA or HBsAg levels [

13]. In fact, certain studies have reported that T123A/C/K/S and P142L/R/S/T mutations in the PreS region lead to decreased HBsAg secretion due to intracellular accumulation [

14].

The prevalence of PreS region deletion mutations was 21.83%. Although genotype C was less prevalent among the co-infected individuals (36.6%), the majority of those with PreS deletions were infected with genotype C (67.4%). A 2017 study from Guangxi [

15] similarly reported a PreS deletion mutation rate of 23% among 61 HIV/HBV co-infected individuals, with genotype C being more common than genotype B. Given that HBV genotypes B and C may differ in pathogenic potential, and that genotype C infection is associated with higher incidences of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma compared to genotype B [

16], these findings may also be influenced by the interactions between HIV and HBV.

Recent studies have established that HBV preS deletion is positively associated with liver fibrosis progression in chronic HBV-infected patients, with preS2 deletions serving as warning indicators for liver fibrosis progression [

8,

17,

18]. Our baseline data showing significantly elevated APRI and FIB-4 scores in patients with PreS deletions, particularly PreS2 deletions (APRI: 1.06, FIB-4: 3.15), strongly supports this association. The age distribution showing older patients in the PreS2 deletion group (median age 50 years) is consistent with the progressive nature of fibrosis development over time.

Longitudinal studies in young HIV patients have demonstrated slow progression of APRI and Fib-4 scores over time, with liver fibrosis scores remaining elevated in HIV-HBV patients regardless of HBsAg status [

19]. Our follow-up data showing persistently elevated fibrosis markers in deletion groups, with statistical significance maintained through 6 years of follow-up, reinforces the prognostic importance of these mutations.

The frequency of PreS2 deletions has been reported to be higher in HBV coinfected patients with genotypes A and C, though not always reaching statistical significance [

20]. Our finding of significantly higher HBV genotype C prevalence in deletion groups (76% overall in deletion patients vs. 28% without deletions) provides robust evidence for this genotype-specific mutation pattern.

HBsAg persistence has been correlated with mutations and deletions in envelope regions that play key roles in immune recognition, suggesting that envelope variability could favor immune escape [

21]. The elevated HBsAg levels observed in PreS deletion groups, particularly PreS2 and PreS12 deletions, support this mechanism of immune evasion.

The limitation of this study is that prognosis was assessed solely through non-invasive clinical examinations, without direct observation of liver pathology. Additionally, the follow-up endpoint did not include progression to hepatocellular carcinoma, which will be the focus of our future research.

In conclusion, the longitudinal nature of study, extending to 6 years of follow-up, addresses a critical gap in understanding the long-term clinical consequences of HBV mutations in HIV coinfection. The persistent elevation of fibrosis markers and liver enzymes in mutation groups suggests that these viral variants may require more intensive monitoring and potentially modified treatment approaches.

Author Contributions

LX: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WY: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LL: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. HF: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou (2024A03J0883; 2025A03J3863; 2023A03J0792; 2024A03J0880; 2023A03J0800); Plan on enhancing scientific research in GMU (GMUCR2024- 02028); The Key Medical Discipline of Guangzhou (Infectious Diseases, 2025-2027).

Acknowledgments

We thank all study participants and data collectors for their cooperation. We thank the BioBank of Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital for biosamples and services.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- LISKER-MELMAN M, WAHED A S, GHANY M G, et al. HBV transcription and translation persist despite viral suppression in HBV-HIV co-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy [J]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md), 2023, 77(2): 594-605.

- HOFMANN E, SURIAL B, BOILLAT-BLANCO N, et al. Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Replication During Tenofovir Therapy Is Frequent in Human Immunodeficiency Virus/HBV Coinfection [J]. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 2023, 76(4): 730-3.

- HONG F, SAIMAN Y, SI C, et al. X4 Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 promotes human hepatic stellate cell activation and collagen I expression through interactions with CXCR4 [J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(3): e33659.

- SINGH K P, ZERBATO J M, ZHAO W, et al. Intrahepatic CXCL10 is strongly associated with liver fibrosis in HIV-Hepatitis B co-infection [J]. PLoS pathogens, 2020, 16(9): e1008744.

- ZHANG F, ZHU H, WU Y, et al. HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus co-infection in patients in the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program, 2010-12: a retrospective observational cohort study [J]. The Lancet Infectious diseases, 2014, 14(11): 1065-72.

- FANG Z L, SABIN C A, DONG B Q, et al. Hepatitis B virus pre-S deletion mutations are a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma: a matched nested case-control study [J]. The Journal of general virology, 2008, 89(Pt 11): 2882-90.

- LIU W, CAI S, PU R, et al. HBV preS Mutations Promote Hepatocarcinogenesis by Inducing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Upregulating Inflammatory Signaling [J]. Cancers, 2022, 14(13).

- LIANG Y J, TENG W, CHEN C L, et al. Clinical Implications of HBV PreS/S Mutations and the Effects of PreS2 Deletion on Mitochondria, Liver Fibrosis, and Cancer Development [J]. Hepatology, 2021, 74(2): 641-55.

- CHEN B, F. Hepatitis B virus pre-S/S variants in liver diseases [J]. World journal of gastroenterology, 2018, 24(14): 1507-20.

- WUNGU C D K, ARIYANTO F C, PRABOWO G I, et al. Meta-analysis: Association between hepatitis B virus preS mutation and hepatocellular carcinoma risk [J]. Journal of viral hepatitis, 2021, 28(1): 61-71.

- JIA J A, ZHANG S, BAI X, et al. Sparse logistic regression revealed the associations between HBV PreS quasispecies and hepatocellular carcinoma [J]. Virology journal, 2022, 19(1): 114.

- NIE Y, DENG X Z, LAN Y, et al. Pre-S Deletions are Predominant Quasispecies in HIV/HBV Infection: Quasispecies Perspective [J]. Infection and drug resistance, 2020, 13(1643-9.

- WANG H, WANG A H, GRESSNER O A, et al. Association between HBV Pre-S mutations and the intracellular HBV DNAs in HBsAg-positive hepatocellular carcinoma in China [J]. Clinical and experimental medicine, 2015, 15(4): 483-91.

- SONG S, SU Q, YAN Y, et al. Identification and characteristics of mutations promoting occult HBV infection by ultrasensitive HBsAg assay [J]. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2025, 63(5): e0207124.

- LI K W, KRAMVIS A, LIANG S, et al. Higher prevalence of cancer related mutations 1762T/1764A and PreS deletions in hepatitis B virus (HBV) isolated from HBV/HIV co-infected compared to HBV-mono-infected Chinese adults [J]. Virus research, 2017, 227(88-95.

- LIN Y C, LI J, IRWIN C R, et al. Vaccinia virus DNA ligase recruits cellular topoisomerase II to sites of viral replication and assembly [J]. Journal of virology, 2008, 82(12): 5922-32.

- LI F, LI X, YAN T, et al. The preS deletion of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is associated with liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic HBV infection [J]. Hepatology international, 2018, 12(2): 107-17.

- CHEN Y, WANG G, LI M, et al. Virological and Immunological Characteristics of HBeAg-Positive Chronic Hepatitis B Patients With Low HBsAg Levels [J]. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 2025, 61(5): 814-23.

- IACOB D G, LUMINOS M, BENEA O E, et al. Liver fibrosis progression in a cohort of young HIV and HIV/ HBV co-infected patients: A longitudinal study using non-invasive APRI and Fib-4 scores [J]. Frontiers in medicine, 2022, 9(888050.

- AUDSLEY J, LITTLEJOHN M, YUEN L, et al. HBV mutations in untreated HIV-HBV co-infection using genomic length sequencing [J]. Virology, 2010, 405(2): 539-47.

- ESCHLIMANN M, MALVé B, VELAY A, et al. The variability of hepatitis B envelope is associated with HBs antigen persistence in either chronic or acute HBV genotype A infection [J]. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology, 2017, 94(115-22.

Table 1.

Basic clinical information for People living with HIV and HBV co-infection Between with Point Mutations and Without Point Mutations.

Table 1.

Basic clinical information for People living with HIV and HBV co-infection Between with Point Mutations and Without Point Mutations.

| |

Overall |

PM |

Non-PM |

p value |

| (n=435) |

(n=317) |

(n=118) |

| |

|

|

|

|

| AGE |

40(33.5-50) |

41(34-50) |

38(33.25-48.75) |

0.184 |

| Sex(male,%) |

376(86.44) |

267(84.23) |

109(92.37) |

0.027 |

| Route of transmission(n,%) |

|

|

|

|

| MSM |

197(45.29) |

138(43.53) |

59(50) |

0.229 |

| HST |

198(45.52) |

152(47.95) |

46(38.98) |

| IDU |

7(1.61) |

6(1.89) |

1(0.85) |

| NA |

33(7.59) |

21(6.62) |

12(10.17) |

| HBV |

|

|

|

|

| HBV genotype(C,%) |

159(36.55) |

49(15.46) |

110(93.22) |

<0.001 |

| HBV DNA(Log10,IU/L) |

7.74(6.68-8.63) |

7.62(6.6-8.53) |

8.06(7.25-8.7) |

0.005 |

| HBsAg(COI) |

2426(1220.5-6604.5) |

2815(1399-6984) |

1504(763.28-4735.25) |

<0.001 |

| HBsAb(+,%) |

7(1.61) |

5(1.58) |

2(1.69) |

0.931 |

| HBeAg(COI) |

263.2(0.09-1395.5) |

72.37(0.09-1348) |

1123.5(11.24-1441.5) |

<0.001 |

| HBeAg(+,%) |

276(63.45) |

183(57.73) |

93(78.81) |

<0.001 |

| HBeAb(COI) |

1.78(0.02-5.98) |

1.3(0.01-5.71) |

4.72(0.85-6.55) |

<0.001 |

| HBeAb(+,%) |

176(40.46) |

143(45.11) |

33(27.97) |

0.001 |

| HBcAb(+,%) |

420(96.55) |

308(97.16) |

112(94.92) |

0.254 |

| Hepatic |

|

|

|

|

| AFP(μg/L) |

2.88(1.94-4.82) |

2.93(1.97-4.82) |

2.67(1.81-4.8) |

0.224 |

| ALT(U/L) |

36(23-61) |

35(23-61) |

38(23-63.25) |

0.755 |

| AST(U/L) |

33(23.1-55.1) |

34(23.2-56) |

32.2(23.25-49.75) |

0.500 |

| T.BIL(μmol/L) |

9.96(7.33-13.59) |

9.87(7.19-13.57) |

9.99(7.82-13.58) |

0.564 |

| PLT(10^9/L) |

181(133-228) |

181(133-224) |

178.5(132.75-236.75) |

0.694 |

| APRI |

0.47(0.28-0.89) |

0.47(0.29-0.91) |

0.47(0.28-0.83) |

0.577 |

| FIB-4 |

1.24(0.76-2.4) |

1.25(0.79-2.42) |

1.2(0.68-2.52) |

0.264 |

Table 1.

Basic clinical information for People living with HIV and HBV co-infection Between different PreS region deletions.

Table 1.

Basic clinical information for People living with HIV and HBV co-infection Between different PreS region deletions.

| |

Overall |

PreS1 del |

PreS2 del |

PreS1+2 del |

w/o del |

p value |

| (n=435) |

(n=46) |

(n=22) |

(n=27) |

(n=340) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AGE |

40(33.5-50) |

40(35-47.75) |

50(42.25-56) |

43(36-55.5) |

39(33-49) |

0.014 |

| Sex(male,%) |

376(86.44) |

9(19.57) |

3(13.64) |

6(22.22) |

41(12.06) |

0.284 |

| Route of transmission(n,%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MSM |

197(45.29) |

19(41.3) |

5(22.73) |

10(37.04) |

163(47.94) |

0.136 |

| HST |

198(45.52) |

21(45.65) |

13(59.09) |

13(48.15) |

151(44.41) |

| IDU |

7(1.61) |

2(4.35) |

0(0) |

0(0) |

5(1.47) |

| NA |

33(7.59) |

4(8.7) |

4(18.18) |

4(14.81) |

21(6.18) |

| HBV |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HBV genotype(C,%) |

159(36.55) |

35(76.09) |

16(72.73) |

13(48.15) |

95(27.94) |

<0.001 |

HBV DNA

(Log10,IU/L) |

7.74

(6.68-8.63) |

7.93

(7.13-8.7) |

6.62

(5.55-7.59) |

7.55

(6.55-8.61) |

7.76

(6.8-8.7) |

0.006 |

| HBsAg(COI) |

2426

(1220.5-6604.5) |

2843.5

(1165-6329.75) |

5984.5

(2745-6576) |

6915

(4286.5-7765) |

2079

(1137.5-6271.5) |

<0.001 |

| Deletion mutation (frequency,%) |

- |

41.11

(21.39-66.78) |

100

(95.34-100) |

84.21

(44.61-100) |

- |

- |

| HBsAb(+,%) |

7(1.61) |

1(2.17) |

0(0) |

2(7.41) |

5(1.47) |

0.149 |

| HBeAg (COI) |

263.2

(0.09-1395.5) |

708.3

(49.99-1295.25) |

2.11

(0.09-61.11) |

59.21

(3.89-712.5) |

456.4

(0.09-1435.5) |

0.015 |

| HBeAg (+,%) |

276(63.45) |

42(91.3) |

12(54.55) |

21(77.78) |

201(59.12) |

<0.001 |

| HBeAb(COI) |

1.78

(0.02-5.98) |

3.04

(1.26-5.63) |

0.21

(0-1.5) |

1.24

(0.63-2.69) |

2.65

(0.01-6.21) |

0.009 |

| HBeAb(+,%) |

176(40.46) |

9(19.57) |

22(100) |

27(100) |

144(42.35) |

<0.001 |

| HBcAb(+,%) |

420(96.55) |

45(97.83) |

22(100) |

27(100) |

326(95.88) |

0.488 |

| Hepatic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AFP(μg/L) |

2.88

(1.94-4.82) |

4.52

(2.39-11.15) |

5.81

(2.13-71.85) |

7.19

(3.53-16.6) |

2.69

(1.91-3.87) |

<0.001 |

| ALT(U/L) |

36

(23-61) |

44

(26.5-86.75) |

46

(26.75-52) |

54

(30-82.5) |

35

(22-59) |

0.039 |

| AST(U/L) |

33

(23.1-55.1) |

40.5

(26-65.5) |

53

(40.25-77.5) |

59

(38.5-82) |

31

(22-47) |

<0.001 |

| T.BIL(μmol/L) |

9.96

(7.33-13.59) |

9.22

(7.38-11.31) |

12.18

(8.78-28.02) |

12.15

(7.83-17.6) |

9.87

(7.21-13.24) |

0.020 |

| PLT(10^9/L) |

181

(133-228) |

182.5

(122.75-229.5) |

124

(91.25-184.75) |

141

(108-199) |

183

(139-230) |

0.014 |

| APRI |

0.47

(0.28-0.89) |

0.54

(0.32-1.27) |

1.06

(0.5-2.09) |

1.02

(0.6-1.5) |

0.43

(0.27-0.72) |

<0.001 |

| FIB-4 |

1.24

(0.76-2.4) |

1.44

(0.83-2.56) |

3.15

(2.08-5.65) |

2.1

(1.2-2.73) |

1.15

(0.74-2.06) |

<0.001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).