1. Introduction

Periodontal disease, being the 11th most prevalent disease worldwide is significant as it affects a large proportion of the population and is associated with several systemic health problems. Poor oral health has been linked to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory infections, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and dementia. As such, addressing periodontal disease can have far-reaching implications for improving overall health and quality of life for individuals and populations [

1]. The chronic inflammatory nature of periodontitis often leads to the infective destruction of the tooth-supporting apparatus, eventually culminating in tooth loss [

2].

While non-surgical and surgical open-flap debridement procedures are the conventional treatment modalities for periodontitis, they have limitations. These treatments aim to limit the further progression of the disease but do not target the reconstruction of the lost periodontal tissues [

3]. Additionally, these procedures can be invasive and require a long healing period, leading to discomfort and decreased quality of life for patients. Regenerative periodontal approaches such as Guided Tissue Regeneration (GTR) and Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) have the potential to overcome these limitations by the use of barrier membrane scaffolds thereby promoting the regeneration of lost periodontal tissues and improving the overall outcomes for patients.

The tensile properties of barrier membrane scaffolds are crucial to ensure the preservation of structural integrity and handling properties and to withstand the tensile forces of tissues and bones. Barrier function relies on the ability of the membranes to function as mechanical barricades that prevent the ingression of the fast-growing gingival epithelial and connective tissue cells into the bone defect thereby maintaining a space for regeneration [

4]. A scaffold should have sufficient stiffness to function as a barrier while having enough plasticity to be manipulated over the defect area. Tensile strength measurements will thus give us details on the resistance of the scaffolds to tensile force so that they can efficiently perform as mechanical interface barriers without collapsing into the tissue defect [

5].

Calcium phosphate bioceramics like β-TCP are popular biomaterials used for bone tissue regeneration. Having a similar inorganic composition to that of bone, these materials are known for their bioactivity, osteoconductivity, and non-reactiveness in living systems. When it comes to the mechanical properties of the ceramics themselves, these materials have properties such as high hardness, strength and stiffness, low fracture toughness, poor fatigue resistance, and low resistance to tensile stresses resulting in insignificant plasticity. [

6] With bioceramics, there is always a tug-of-war between bioactivity and mechanical properties, and enhancement of one property results in compromising the other. Current research strategies are working towards finding a balance between these two properties of bioceramics to expand the boundaries of their application. [

7]

Contrary to their bulk properties, in composite systems, bioceramics are known to improve and enhance the overall mechanical properties. A study has shown that reinforcement of β-TCP into silk fibroin scaffold material, not only improved the bioactivity but also have improved the mechanical properties of the scaffolds in terms of compressive strength [

8]. Nanoparticles have revolutionized the field of tissue engineering from enhancing the overall properties of biomaterials to gene delivery and molecular detection because of their size-dependent properties.[

9] Incorporating nanoparticles in scaffold biomaterials has shown promising enhancement of properties. The bioactivity of β-TCP at the nanoscale level in nanocomposite scaffolds has been well documented, in terms of osteoconductivity and tissue ingrowth. [

10]. However, there is very little evidence of their reinforcement effect at the nanoscale at various concentrations, on the tensile properties of GTR/GBR membranes for periodontal regeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was aimed at answering the following review question: What is the effect of beta-tricalcium phosphate nanoparticle reinforcement on the tensile strength of bioresorbable barrier membrane scaffolds for guided tissue and bone regeneration?

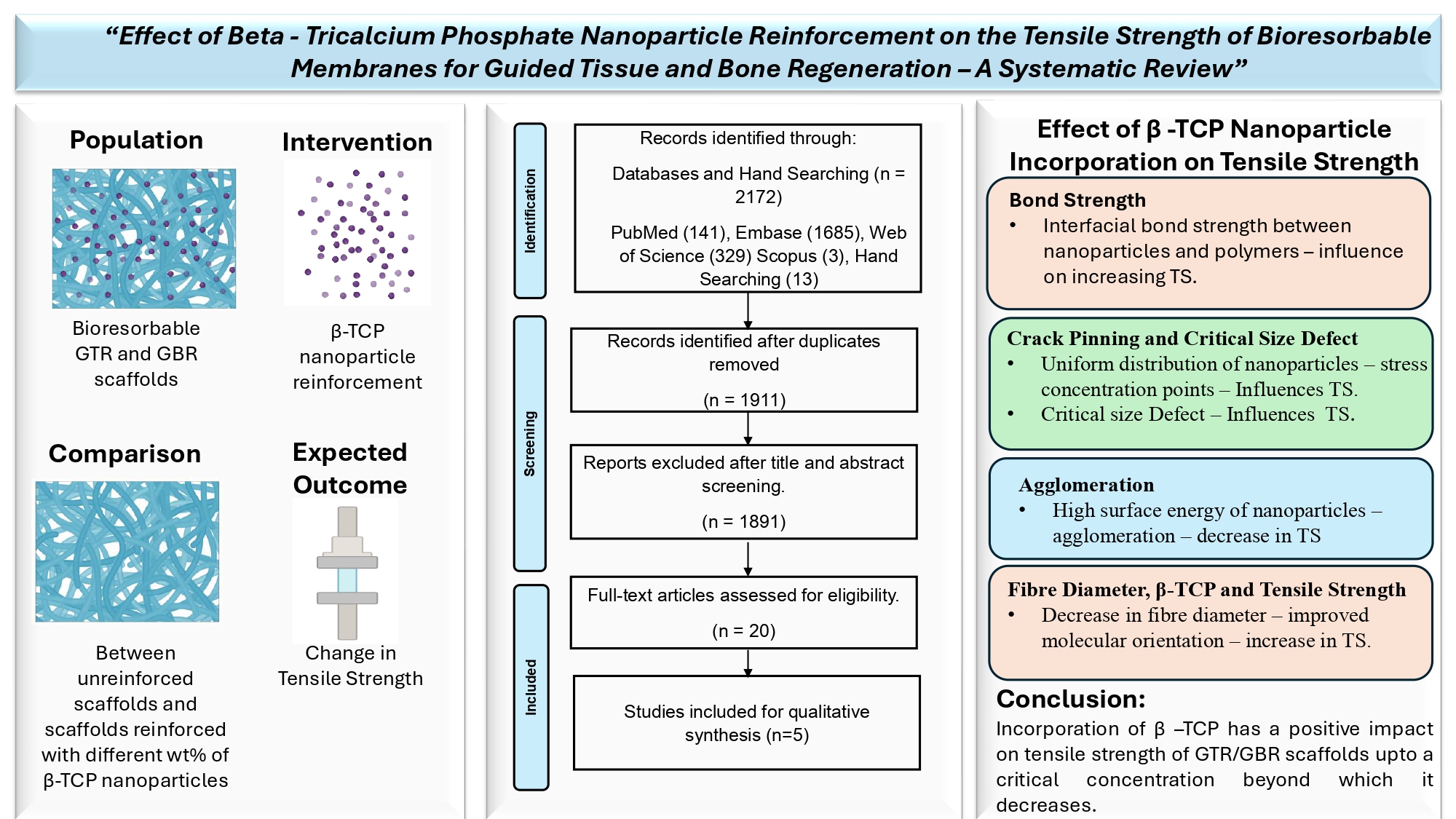

According to the PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) statement, an unregistered protocol was prepared, and a literature search was conducted using the PICO approach: Population–bioresorbable GTR and GBR scaffolds, Intervention – beta-tricalcium phosphate nanoparticle reinforcement, Comparison – between unreinforced scaffolds and scaffolds reinforced with different wt% of beta-tricalcium phosphate nanoparticles, Outcome – change in tensile strength, Study design – in vitro experimental studies.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The studies were selected based on eligibility criteria such as studies in the English language, in-vitro experimental studies that evaluated the properties of only bioresorbable GTR and GBR barrier membrane scaffolds, reinforcement of β-TCP nanoparticles at various concentrations, and studies that evaluated tensile strength as one of their parameters. Those studies that involved reinforcement of nanoparticles other than β - TCP, studies that involved reinforcement of β - TCP particles at sizes other than the nanoscale, studies that included scaffolds other than GTR/GBR membranes, in vivo studies, clinical trials, and non-dental studies were excluded.

2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed in electronic databases PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science (Core Collection) for relevant reports published in the English language till the month of October 2022 with no restriction to publication year limit. The search strategy was developed in PubMed using keywords and Mesh terms, and later the search was translated for other databases without restriction to filters during the search. Hand-searching of articles in relevant journals related to material science was also performed. The keywords employed included “Beta – Tricalcium phosphate”, “Nanoparticles”, “Tissue Regeneration”, “Guided Tissue Regeneration” and “Membranes”. The details of the text block approach of the search strategy employed is given in

Table 1.

2.3. Data Collection, Screening, and Selection:

Data was imported in CSV format and screened using the Rayyan software tool. Following the removal of duplicate records, two independent reviewers (RSV and PMT) screened the titles of records in the specified databases according to the eligibility criteria. The second step involved screening abstracts of the included titles, followed by a full-text screening of relevant reports by the investigators. The inclusion of studies was based on mutual agreement between the investigators. Disagreements among the reviewing investigators regarding study selection were resolved through discussion.

2.4. Risk Of Bias:

The quality appraisal for the included reports was performed by two authors (RSV and PM) individually and in case of discrepancy, it was resolved by a third author. The risk of bias assessment was carried out using the QUIN tool (Quality Assessment Tool for In-Vitro Studies) [

11]. The reports were evaluated on the basis of a 12-scale scoring criteria mentioned in

Table 2. Studies were scored as 0 (not specified), 1 (inadequately specified), 2 (adequately specified), and NA (not applicable) for each criterion and were graded based on their final scores as high risk (<50%), moderate risk (50% - 70%) and low risk (>70%).

Table 2.

QUIN (Quality Assessment Tool for In-Vitro Studies).

Table 2.

QUIN (Quality Assessment Tool for In-Vitro Studies).

| AUTHOR/ YEAR

|

Masoudi Rad M et al., 2017 |

Ezati M et al., 2018 |

Yu S et al., 2019 |

Tayebi M et al., 2021 |

Castro V O et al., 2020 |

| ITEM/GRADE

|

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 3 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| 4 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

| 5 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

| 6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 7 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| 8 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| 9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 11 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 12 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| Total score |

9 |

8 |

9 |

9 |

12 |

| Grading |

High Risk |

High Risk |

High Risk |

High Risk |

Medium Risk |

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis:

A standard data extraction form was created by the reviewing investigators and used for data extraction. The parameters that were included in the data extraction form were study/author, date of publication, β-TCP reinforcement method, wt% of β TCP incorporated, Test conditions (Wet/Dry Specimen), Specimen Size, Instrument Used, Mechanical Load, Strain Rate, Gauge Length, Tensile strength of control MPa, Tensile strength β - TCP MPa, secondary outcome and other properties evaluated and conclusion. The primary outcome, ultimate tensile strength of GTR/GBR membranes reinforced with β-TCP nanoparticles, was given priority during data synthesis. If it was reported in the selected studies, Young's modulus was taken as the secondary outcome.

3. Results

3.1. Data Selection

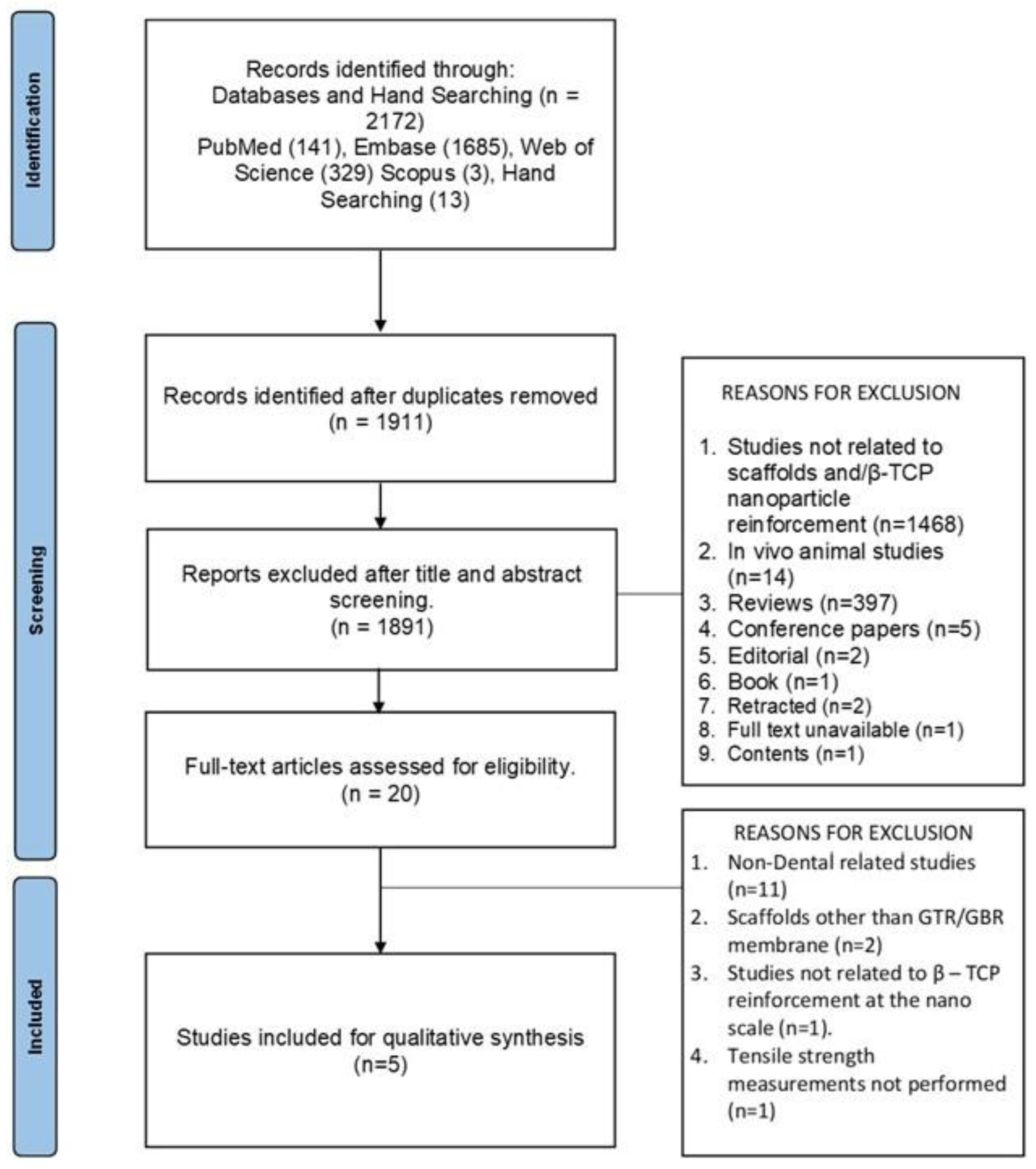

The PRISMA flow diagram for searches from databases and other sources is outlined in

Figure 1. Out of the total of 2172 records identified from databases and hand searching, 1911 articles were subjected to title and abstract screening after duplicate removal. On the basis of specific exclusion reasons 1891 articles were excluded and 20 full-text reports were assessed for eligibility. Out of the 20 studies 15 studies were excluded based on exclusion reasons such as non-dental studies (n=11), scaffolds other than GTR/GBR membranes (n=2), studies not related to β-TCP reinforcement at the nanoscale (n=1) and tensile strength measurements not performed (n=1). After full-text screening 5 articles were included based on the eligibility criteria [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The high clinical and methodological heterogeneity in terms of the matrix material used, the use of wet and dry samples for assessment, different measurement criteria used, and the lack of mean values projected in certain studies led to the inability to perform a meta-analysis.

3.2. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias assessment was done using the QUIN tool (Quality Assessment Tool for In-Vitro Studies) [

11]. The analysis was done based on 12 scale scoring criteria and the final score was calculated using the formula, Final score= (Total score×100)/ (2×number of criteria applicable) and studies were graded according to the final scores. Four of the five included studies were deemed high-risk and one moderate risk, due to lack of details on sample size calculation, operator information, outcome assessor details, and blinding. There was no mention of sample size calculation in any of the articles. The standard of outcome measurement used was only mentioned in one study [

14].

Table 3. gives the summary of the data extracted from the 5 included reports and

Table 4. details the overall effect of β-TCP nanoparticle reinforcement on the tensile strength in all the included reports at various concentrations and their reasons. Factors such as interfacial bond strength, crack pinning and crack deflection, and agglomeration were reported to influence the tensile strength.

Taybei M et al., 2021 incorporated β-TCP nanoparticles into the matrix material at concentrations of 3wt%, 5wt% and 7 wt%, and reported an increase in tensile strength up to a concentration of 5wt% and a further decline in the tensile properties as the concentration increased to 7wt%. The increase in tensile strength was attributed to the interfacial bond strength between the nanoparticles and the molecular chains.

Yu S et al., 2019 reported an increase in ultimate tensile strength and Young’s modulus with the increasing concentration of β-TCP from 0wt% to 10 wt% and 50wt%. The homogenous distribution of nanoparticles that acted as stress concentration points when tensile stresses were applied and the phenomenon of crack pinning and crack deflection was attributed to this mechanism. A further increase to 90wt% deteriorated the properties due to agglomeration.

Four out of the five included reports stated that β-TCP tended to agglomerate at higher concentrations and the concentration at which agglomeration and decline of tensile strength was observed, varied from study to study. The authors have reported evidence of agglomeration and decline of tensile strength at 7wt% (Tayebi M et al.,), 15wt% (Masoudi Rad M et al.,) 20wt% (Castro V O et al.,) and 90 wt% (Yu S et al.,) β-TCP nanoparticle reinforcement.

The five studies that were included for synthesis, used different natural and synthetic polymers and their blends, different fabrication techniques, and different tensile testing criteria which impeded going for a meta-analysis. Hence a narrative synthesis was performed to identify the factors that influence the tensile strength of GTR/GBR membranes and the effect of β-TCP nanoparticle reinforcement at various concentrations on the tensile strength of different polymer scaffold biomaterials used for periodontal regeneration. The factors identified have been discussed under various subheadings.

4. Discussion

Tensile strength refers to the resistance of a material to withstand tensile forces. The manipulability of GTR/GBR membranes in a clinical setting is directly influenced by the tensile strength measurements. The bioresorbable membranes that are currently commercially available have been reported to have a tensile strength between 3.5 MPa to 22.5 MPa [

17]. Tensile strength of a biomaterial can vary depending on the material, thickness, method of preparation, testing set up and criteria. Hence to obtain precise comparative results these tests should be carried out following a standard protocol. Tensile testing is normally carried out using the ASTM standard depending on the type of polymer composite. ASTM D638 is recommended for discontinuous, mouldable, randomly oriented and low reinforcement to volume composites whereas ASTM D3039 is recommended for highly oriented fibre reinforced composites with high tensile modulus [

18]. Among the included reports, only one study (Tayebi et al.,) reported the ASTM criteria that was followed for their tensile testing. ASTM D882-02 which is the testing criteria for thin plastic sheeting has been used by Tayebi et al., [

14].

Variation in the matrix/substrate material can greatly influence the tensile strength of a scaffold. In general, there is a lot of variation in tensile strengths between polymers, and synthetic polymers materials tend to have a higher tensile strength than natural polymers [

19]. The tensile strengths of some of the commonly used polymer materials used as biomedical membranes is tabulated in

Table 5. In order to enhance and improve their properties, these polymers are usually modified or blended with other polymer materials. All the five included studies have used different polymers and polymer blends as matrix materials for their nanocomposite biomaterials (

Table 4). A study evaluated the tensile strength of Poly (lactic – co-glycolic acid) for GTR applications, fabricated using solvent casting method and found that dried PLGA membranes had a tensile strength of 16.7± 1.9 MPa [

33]. This value was comparatively higher than pure PLGA control membranes without β-TCP reinforcement in the study by Castro V O et., which was 3.04± 1.74 MPa [

15].

Among the other synthetic polymers, Polyhydroxy butyrate (PHB) which was used in the study by Tayebi M et al., is known for its rigidity and brittleness [

13,

18]. Their study recorded a tensile strength of pure PHB without reinforcement to be 1.3744± 0.37 MPa which was lower compared to the matrix materials used in the other included studies. Yu S et al., has used PEGylated Polyglycerol sebacate having a tensile strength of 6.59± 0.34 MPa. The introduction of PEG fragments in the PGS backbone (PEGylation) is done to improve the hydrophilicity and controlled degradation behaviour of Polyglycerol Sebecate. However, it has been reported in a study that PEGylation decreases the tensile strength of PGS to about 690± 160 kPa [

34].

Ezati M et al., has used a blend of synthetic (PCL) and natural polymers (gelatin and chitosan). Their results show that this electrospun polymer blend comprising of PCL(40 wt%), Chitosan (20 wt%) and Gelatin (40 wt%) has a tensile strength approximately of 6.5 MPa [

13]. In Masoudi Rad M et al., study, the polymer blend of PCL and PGS in the ratio of 50:50 had a tensile strength of roughly around 1 MPa [

16]. Thus different substrate/matrix materials have different tensile strengths and their blends in different ratios and modifications like cross-linking agents can also alter the tensile properties of the biopolymers. Out of the 5 studies that were included, the dried PEGylated poly (glycerol sebecate) membrane scaffold material had the highest tensile strength.

Table 5.

Tensile strengths of commonly used synthetic and natural matrix materials for biomedical membranes.

Table 5.

Tensile strengths of commonly used synthetic and natural matrix materials for biomedical membranes.

| MATERIAL |

FABRICATION METHOD |

TENSILE STRENGTH

|

REINFORCEMENT |

EFFECT OF REINFORCEMENT |

REFERENCE |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) |

Electrospinning |

9.5±1.75 MPa |

Silica nanoparticles |

Increase in tensile strength with 20wt% nanosilica and decreased tensile strength on further increase in concentration to 33wt% |

Castro AGB et al., 2018 [20] |

| Polylactide (PLA) |

Electrospinning |

0.063±0.004 MPa |

Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles |

Increase in tensile strength with increasing concentration of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles and highest strength observed at 20wt% concentration. |

Jeong et al., 2008 [21] |

Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

(PLGA) |

Electrospinning |

3.04±1.74 MPa |

β-TCP nanoparticles |

Increase in tensile strength at 5wt% β-TCP nanoparticle concentration and decrease in tensile strength at 10wt% and 20wt% concentrations. |

Castro VO et al., 2020 [15] |

Polyhydroxybutyrate

(PHB) |

Electrospinning |

1.3744±0.37 MPa |

β-TCP nanoparticles |

Increase in tensile strength from unreinforced to reinforced scaffolds at 3wt% and 5wt% and decline at 7wt% |

Tayebi M et al., 2021 [14] |

Polyetherurethanes

(PU) |

Casting and freeze drying |

4.91±0.49 MPa |

Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles |

Increase in tensile strength with increasing concentration of nanohydroxyapatite and decline on further increase. |

Liu H et al., 2010 [22] |

Polyvinyalchohol

(PVA) |

Casting |

28.2±5.3 MPa |

Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles |

Increased tensile strength observed at 5wt% and 10wt% concentration and decreased on further increase of nanohydroxyapatite. |

Zeng S et al., 2011 [23] |

Polypropylene Carbonate

(PPC) |

Casting |

17 MPa |

Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles |

Increased tensile strength with increase in concentration at 30wt% and 40wt% |

Zou Q et al., 2017 [24] |

| Collagen |

Casting and freeze drying |

0.43 MPa |

Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles |

Increase in tensile strength by 4 times at 20wt% and 6 times at 40 wt% concentration of nanohydroxyapatite. |

Song JH et al., 2007 [25] |

| Silk fibroin |

Electrospinning |

0.22N/mm |

Nano silver fluoride |

Increase in tensile strength at 1% nanosilver fluoride |

Pandey A et al., 2021 [26] |

| Fibrinogen |

Casting |

45kPa |

Unreinforced |

- |

Elvin CM et al., 2009 [27] |

| Gelatin |

Electrospinning |

4.6±1.4 MPa |

Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles |

Increase in tensile strength at 20wt% and decreased tensile strength at 40wt% concentration of nanohydroxyapatite. |

Kim HW et al., 2005 [28] |

| Keratin |

Doctor Blade Casting and Wet Spinning Method |

3.5 MPa |

Unreinforced |

- |

Ma B et al., 2016 [29] |

| Starch |

Casting |

48.56± 0.50 MPa |

Unreinforced |

- |

Rodrigues S et al., 2021 [30] |

| Chitosan |

Casting |

Dry – 56.7±3.9 MPa

Wet – 6.3±0.8 MPa |

Bioactive glass |

Decrease in tensile strength at 0.3% (w/v) concentration of bioactive glass |

Mota J et al., 2012 [31] |

| Cellulose |

Casting and coagulation |

103± 8.3 MPa |

Unreinforced |

- |

Li X et al., 2019 [32] |

4.1. Fabrication Method and Tensile Strength:

The fabrication method also determines the tensile strength of a biomaterial. A study evaluated the tensile strength of polycaprolactone fabricated using 2 different fabrication methods. It was observed that compression moulded electrospun samples exhibited higher tensile strength when compared with samples fabricated with only compression moulding technique. This was attributed to the nanofibre structured phenomenon that was observed in the electrospun compression moulded materials. The advantage of electrospinning combined with the compression moulding technique could increase the density of the fibres and therefor contributing to the increase in tensile strength [

35]. Among the included reports 4 studies have used electrospinning fabrication method and one study (Yu S et al.,) has used prepolymer mixing in-situ crosslinking and casting method of fabrication, which reported a higher tensile strength compared to the electrospun membranes. This disparity maybe due to the thickness of the electrospun membranes and their packing density which also plays an important role in determining the tensile strength [

36].

4.2. Fibre Alignment and Tensile Strength:

Electrospinning has become a popular method of scaffold fabrication as it produces a structural morphology that mimic ECM. It has been reported that fibre alignment in GTR membranes can also influence the mechanical properties. Aligned fibres have shown to exhibit significantly higher tensile strength than randomly oriented fibres due to the fact that alignment of fibres causes more force resistance in the direction of loading [

35]. All the 4 included studies that used electrospinning fabrication technique shows evidence of randomly oriented electrospun fibres [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]

4.3. Effect of β -TCP Nanoparticle Incorporation on Tensile Strength:

4.3.1. Bond Strength and β-TCP Nanoparticle Reinforcement:

All the included studies have reported that β-TCP nanoparticle reinforcement does influence the tensile properties of the substrate materials. It has been reported that the interfacial bond strength between the nanoparticles and the molecular chains of the polymer matrix depends on the uniform dispersion of the nanoparticles within the matrix material which in turn significantly influences and increases the tensile strength. However, agglomeration and ununiform distribution, can cause weak points in the matrix and interfere with, or break the bond strength, thereby resulting in a decrease in tensile strength [

37].

Tayebi M et al., in their study incorporated various concentrations of 3wt%, 5wt% and 7wt% β-TCP in their bilayered GTR/GBR membrane. With the increase in β-TCP concentration up to 5wt%, the mechanical properties increased, which was attributed to an increase in bonding between nanoparticles and molecular chains. This concentration provided thin fibres and uniform distribution. However, a further increase in concentration to 7wt% decreased the mechanical properties due to the agglomeration of the nanoparticles observed at this concentration [

13].

4.3.2. Crack Pinning and Critical Defect Size on Tensile Strength:

Yu S et al., in their study, the authors noticed an increase in ultimate tensile strength and Young’s modulus with the increasing concentration of β-TCP incorporation. The homogenous distribution of the nanoparticles that acted as stress concentration points when tensile stresses were applied, and the phenomenon of crack pinning and crack deflection was imputed to this mechanism. However, when the concentration increased from 50wt% to 90 wt% there was a deterioration of mechanical properties because of the agglomeration of the particles observed at 90 wt% concentration.

A non-dental study evaluated the tensile strength of β-TCP nanoparticle reinforced Poly – L – Lactide (PLLA) biomaterial and reported that β-TCP reinforcement at 0.25 wt% showed a slight increase in tensile strength due to the ability of β-TCP to act as barrier to molecular movement. However, upon further increase to 1 wt%, there was a decrease in tensile strength. The authors explained that critical defect size of a polymer largely affects the tensile properties and increasing the concentration of β-TCP nanoparticles can result in stress concentration points due to agglomeration that can disrupt the polymer structure eventually resulting in decreased tensile strength [

38].

4.3.3. Agglomeration:

Agglomeration of β-TCP nanoparticles occurs at higher concentrations and this agglomeration tends to affect the above-mentioned properties of interfacial bonding and formation of stress concentration points [

39]. Four out of the five included reports stated that β TCP tended to agglomerate at higher concentrations

. In general nanoparticles tend to decrease the high surface energy caused by their increased surface volume to area ratio by the process of agglomeration, thereby increasing their size and decreasing the surface area. The agglomerated nanoparticles are held together by weak van der Walls forces, surface tension and electrostatic interactions [

40]. Across the four included reports, it was observed that as the concentration of nanoparticles increased beyond a critical concentration, it resulted in agglomeration which in turn was positively linked to a decline in tensile strength. This concentration varied from study to study with 7wt% (Tayebi M et al.,), 15wt% (Masoudi Rad M et al.,) 20wt% (Castro V O et al.,) and 90 wt% (Yu S et al.,). What was unusual was the fact that in one of the studies, agglomeration was not reported at 50wt %, which was a concentration that was comparatively higher than the highest concentration at which agglomeration was reported in the other included reports [

12]. Their study only reported agglomeration at a much higher concentration of 90wt%. Another fact is that in their study there was no usage of capping agents or surfactants during the fabrication process which can allow such a large concentration of nanoparticles to be incorporated. One of the parameters that will influence agglomeration is the dispersion of nanoparticles within the polymer matrix and it was reported in a study that β-TCP nanoparticles are difficult to be uniformly dispersed in the polymer, thus creating pores and uneven force which eventually affects its properties. Therefore it is recommended to improve the method of dispersion of these particles [

41]. The dispersion methods used for homogenization includes 20 minutes ultrasound dispersion (Masoudi Rad M et al.,), sonication using ultrasonic probe for 5 minutes after mixing (Castro VO et al.,), slow magnetic stirring for 24 hours (Ezati M et al.,) and stirring with plastic rod followed by sonification for 10 minutes (Yu S et al.,).

4.3.4. Fibre Diameter, β-TCP and Tensile Strength:

Fibre diameter has shown to influence the tensile properties of electrospun fibres. It has been reported that when the diameter of the fibres decreases, it results in improved molecular orientation and crystallinity of the polymers, thereby increasing the tensile strength [

42]. Masoudi Rad M et al., has reported that reinforcement of β-TCP nanoparticles at 10wt% and 5wt% concentration reduced the fibre diameter to 453±18nm and 361±23nm respectively. This can be correlated with the increase in tensile strengths at these concentrations. However, a further increase in concentration of β-TCP to 15wt% resulted in larger diameter fibres and a decrease in tensile strength. It was reported in a study that the incorporation of silver nanoparticles in polymer resulted in an increase in charge density that subjects the jets to stronger stretching forces that resulted in thinner fibres with decrease in fibre diameter during the electrospinning process [

43]. Similarly this phenomenon could have been due to the fact that β-TCP has been reported to have a higher charge density [

44]. These findings suggest that reinforcement of β-TCP nanoparticles up to an optimal concentration can result in smaller diameter fibres which in turn can positively influence the tensile strength [

15]. A similar finding can be seen in the other 2 included reports that used electrospinning method of fabrication [

13,

14].

4.4. Effect of Β-TCP on Properties Other Than Tensile Strength:

The current evidence showed that incorporation of β-TCP nanoparticles not only affected the tensile strength, but also had an influence on surface morphology, hydrophilicity, in-vitro degradation and cell adhesion and proliferation. Contact angle, a measure of surface hydrophilicity, largely depends on factors such as surface roughness, particle size and shape and also surface chemistry.

48 Four out of the five studies reported an increase in surface hydrophilicity with the increasing concentration of β-TCP nanoparticles [

12,

13,

14,

16]. Ezati M et al., compared the surface roughness of the β-TCP nanoparticle reinforced scaffolds with their contact angles and reported that incorporation of the nanoparticles increased the surface roughness of the membranes and as the concentration of β-TCP nanoparticle was increased, the surface roughness increased which in turn resulted in a decrease in contact angle and an increase in hydrophilicity [

13]. In another study, the author concluded the inherent hydrophilic property of β-TCP nanoparticles was responsible for the decrease in contact angle [

15]. It was postulated that increasing the concentration of β-TCP nanoparticles, increased the surface roughness and influenced the surface tension of the substrate material, which in turn influenced the surface hydrophilicity [

12,

13,

14,

16].

In – vitro degradation test is an important test, especially with bioresorbable membranes as the rate of degradation should parallel the formation of new tissue in the defect area. Too fast and too slow degradation both will have their influence in the healing process. Yu S et al., found an inverse relationship between weight loss and β-TCP concentration. The slow degradation of β-TCP compared to the polymer was responsible for the slow degradation of the reinforced membranes [

12].

Another important factor is cell adhesion and proliferation. β-TCP in general is known for its good biocompatibility and osteogenic properties. It was observed that cell adhesion property increased with an increase in concentration of β-TCP nanoparticle reinforcement. This was attributed to the increase in surface roughness and hydrophilicity produced by these particles [

12,

13].

Ezati M et al., reported that cell proliferation was optimal at 3 wt% concentration of β-TCP at day 7 of culture [

13]. It was also observed that the level of alkaline phosphatase used in osteogenic differentiation test also increased with β-TCP nanoparticle reinforcement, especially at 50wt% concentration as reported by

Yu S et.,[

12].

The concentration of β-TCP nanoparticles is a critical factor in biomedical applications. The optimal concentration can affect the physicochemical properties, mechanical strength, and biocompatibility of the material. Too low a concentration may result in poor mechanical properties and insufficient cell attachment, while too high a concentration can lead to agglomeration, decreased biocompatibility, and other negative effects. Therefore, determining the optimal concentration of β-TCP nanoparticles is crucial for the success of biomedical applications, such as bone tissue engineering and drug delivery systems.

Overall, the concentrations of β-TCP nanoparticles used varied from 1wt%, 3wt%, 5wt%, 7wt%, 10wt%, 15wt%, 20wt%, 50wt% and 90wt% across the 5 included reports. In four of the five reports that were included, 5wt% β-TCP was used, resulting in improved tensile strength, bioactivity, and physicochemical properties. The highest cell attachment, proliferation, and expression of Type I collagen in 3wt% β-TCP were reported by Ezati M et al. However, when it came to mechanical properties 5wt% concentration had the highest tensile strength exhibited in their study. Decreased percentage of fibre density and porosity along with decreased mechanical strength and ununiform thick fibres were observed at 7 wt% concentration in Tayebi M et al., study. At 10wt% concentration, good physical, mechanical properties along with cell behaviour was observed in one study (Maryam masoudi Rad et al.,). However the same concentration was reported to have a decrease in mechanical properties compared to 5 wt% concentration and lower cell proliferation in another study. (Castero et al.,). Agglomeration, decrease in mechanical properties and decrease in cell proliferation were observed at 15wt% concentration. (Maryam Masoudi Rad) Highest cell metabolic activity and decreased mechanical properties were observed at 20 wt% concentration. (Castero et al.,). Although in Yu S et al., study they have reported good biocompatibility at 50wt% and 90wt% concentration, these are still very high concentrations exceeding the critical concentration mentioned in the rest of the reports. Thus the optimal concentration that was observed to have the ideal physico-mechanical and biocompatibility was at 5wt% in all the four included reports that used this concentration.

5. Conclusions

The tensile strength of a GTR/GBR membrane depends on many factors such as scaffold matrix material, their inherent properties, modifications, cross-linking agents, fabrication methods, testing criteria used, reinforcement materials, and their synthesis and dispersion within the matrix. Reinforcement of nanoparticles like β-TCP nanoparticles, is evolving to modify and achieve desirable properties for GTR/GBR applications. It is clear from the available evidence that β-TCP nanoparticle reinforcement does have a positive influence on the tensile strength of GTR/GBR membranes at lower concentrations. However, increasing the concentration tends to have the opposite effect. In all 5 studies, this effect is observed at different concentrations. Based on the limitations of the study, it can be concluded that the ideal concentration of β-TCP nanoparticles required to improve the tensile strength of barrier membranes is not precisely known. Hence it is always better to reinforce the particles from the lowest possible concentration and work the way up to get the desirable effect. It is also observed that β TCP nanoparticles do have other desirable properties that can be exploited to achieve an ideal scaffold membrane for the regeneration of tissues.

Funding

The study has not been supported by any funding agency.

Data Availability Statement

The manuscript contains all the data associated with the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest pertaining to the study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GTR |

Guided Tissue Regeneration |

| GBR |

Guided Bone Regeneration |

| β-TCP |

Beta – Tricalcium Phosphate |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QUIN |

Quality Assessment Tool for In-Vitro Studies |

| PCL |

Poly Caprolactone |

| PLA |

Polylactide |

| PLGA |

Poly(lactic – co-glycolic acid) |

| PHB |

Polyhydroxybutyrate |

| PU |

Polyurethanes |

| PVA |

Polyvinylalchohol |

| PPC |

Polypropylene Carbonate |

References

- Nazir M, Al-Ansari A, Al-Khalifa K, Alhareky M, Gaffar B, Almas K. Global prevalence of periodontal disease and lack of its surveillance. The Scientific World Journal. 2020;2020:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. The Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1809–20. [CrossRef]

- Villar CC, Cochran DL. Regeneration of periodontal tissues: Guided tissue regeneration. Dental Clinics of North America. 2010;54(1):73–92. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki JI, Abe GL, Li A, Thongthai P, Tsuboi R, Kohno T, Imazato S. Barrier membranes for tissue regeneration in dentistry. Biomater Investig Dent. 2021;8(1):54-63. [CrossRef]

- Raz P, Brosh T, Ronen G, Tal H. Tensile properties of three selected collagen membranes. BioMed Research International. 2019;2019:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Vaiani L, Boccaccio A, Uva AE, Palumbo G, Piccininni A, Guglielmi P, Cantore S, Santacroce L, Charitos IA, Ballini A. Ceramic Materials for Biomedical Applications: An Overview on Properties and Fabrication Processes. J Funct Biomater. 2023 Mar 4;14(3):146. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Feng C, Cao Q, Wang W, Ma Z, Wu Y, He T, Jing Y, Tan W, Liao T, Xing J, Li X, Wang Y, Xiao Y, Zhu X, Zhang X. Strategies of strengthening mechanical properties in the osteoinductive calcium phosphate bioceramics. Regen Biomater. 2023 Feb 17;10: rbad013. [CrossRef]

- Lee DH, Tripathy N, Shin JH, Song JE, Cha JG, Min KD, Park CH, Khang G. Enhanced osteogenesis of β-tricalcium phosphate reinforced silk fibroin scaffold for bone tissue biofabrication. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;95:14-23. [CrossRef]

- Hasan A, Morshed M, Memic A, Hassan S, Webster TJ, Marei HE. Nanoparticles in tissue engineering: applications, challenges and prospects. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:5637-55. [CrossRef]

- Ibara A, Miyaji H, Fugetsu B, Nishida E, Takita H, Tanaka S, Sugaya T, Kawanami M. Osteoconductivity and biodegradability of collagen scaffold coated with nano-βTCP and fibroblast growth factor 2. J Nanomaterials 2013; ID639502: 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Sheth VH, Shah NP, Jain R, Bhanushali N, Bhatnagar V. Development and validation of a risk-of-bias tool for assessing in vitro studies conducted in dentistry: The QUIN. J Prosthet Dent. 2022 Jun 22:S0022-3913(22)00345-6. [CrossRef]

- Yu S, Shi J, Liu Y, Si J, Yuan Y, Liu C. A mechanically robust and flexible PEGylated poly(glycerol sebacate)/β-TCP nanoparticle composite membrane for guided bone regeneration. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7(20):3279–90. [CrossRef]

- Ezati M, Safavipour H, Houshmand B, Faghihi S. Development of a PCL/gelatin/chitosan/β-TCP electrospun composite for guided bone regeneration. Prog Biomater. 2018;7(3):225–37. [CrossRef]

- Tayebi M, Parham S, Abbastabbar Ahangar H, Zargar Kharazi A. Preparation and evaluation of bioactive bilayer composite membrane PHB / Β-TCP with ciprofloxacin and vitamin D3 delivery for regenerative damaged tissue in periodontal disease. J Appl Polym Sci. 2022;139(3):51507. [CrossRef]

- Castro VO, Fredel MC, Aragones Á, de Oliveira Barra GM, Cesca K, Merlini C. Electrospun fibrous membranes of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) with β-tricalcium phosphate for guided bone regeneration application. Polym Test. 2020;86:106489. [CrossRef]

- Masoudi Rad M, Nouri Khorasani S, Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L, Prabhakaran MP, Foroughi MR, Kharaziha M, et al. Fabrication and characterization of two-layered nanofibrous membrane for guided bone and tissue regeneration application. Mater Sci Eng C. 2017;80:75–87. [CrossRef]

- Zhang HY, Jiang HB, Ryu JH, Kang H, Kim KM, Kwon JS. Comparing Properties of Variable Pore-Sized 3D-Printed PLA Membrane with Conventional PLA Membrane for Guided Bone/Tissue Regeneration. Materials. 2019;12(10):1718. [CrossRef]

- Rahman R, Firdaus SZ, Putra S. Tensile properties of natural and synthetic fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Mechanical and Physical Testing of Biocomposites, Fibre-Reinforced Composites and Hybrid Composites. 2019;81–102. [CrossRef]

- Reddy MSB, Ponnamma D, Choudhary R, Sadasivuni KK. A Comparative Review of Natural and Synthetic Biopolymer Composite Scaffolds. Polymers. 2021;13(7):1105. [CrossRef]

- Castro AGB, Diba M, Kersten M, Jansen JA, Van Den Beucken JJJP, Yang F. Development of a PCL-silica nanoparticles composite membrane for Guided Bone Regeneration. Mater Sci Eng C. 2018; 85:154–61. [CrossRef]

- Jeong SI, Ko EK, Yum J, Jung CH, Lee YM, Shin H. Nanofibrous Poly(lactic acid)/Hydroxyapatite Composite Scaffolds for Guided Tissue Regeneration. Macromol Biosci. 2008;8(4):328–38. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Zhang L, Li J, Zou Q, Zuo Y, Tian W, et al. Physicochemical and Biological Properties of Nano-hydroxyapatite-Reinforced Aliphatic Polyurethanes Membranes. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2010 Jan;21(12):1619–36. [CrossRef]

- Zeng S, Fu S, Guo G, Liang H, Qian Z, Tang X, et al. Preparation and Characterization of Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Poly(vinyl alcohol) Composite Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2011;7(4):549–57. [CrossRef]

- Zou Q, Liao J, Li J, Li Y. Evaluation of the osteoconductive potential of poly(propylene carbonate)/nano-hydroxyapatite composites mimicking the osteogenic niche for bone augmentation. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2017;28(4):350–64. [CrossRef]

- Song JH, Kim HE, Kim HW. Collagen-apatite nanocomposite membranes for guided bone regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;83B(1):248–57. [CrossRef]

- Pandey A, Yang TS, Yang TI, Belem WF, Teng NC, Chen IW, et al. An Insight into Nano Silver Fluoride-Coated Silk Fibroin Bioinspired Membrane Properties for Guided Tissue Regeneration. Polymers. 2021;13(16):2659. [CrossRef]

- Elvin CM, Brownlee AG, Huson MG, Tebb TA, Kim M, Lyons RE, et al. The development of photochemically crosslinked native fibrinogen as a rapidly formed and mechanically strong surgical tissue sealant. Biomaterials. 2009;30(11):2059-65. [CrossRef]

- Kim HW, Song JH, Kim HE. Nanofiber Generation of Gelatin-Hydroxyapatite Biomimetics for Guided Tissue Regeneration. Adv Funct Mater. 2005;15(12):1988–94. [CrossRef]

- Ma B, Qiao X, Hou X, Yang Y. Pure keratin membrane and fibers from chicken feather. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;89:614–21. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues S, Fornazier M, Magalhães D, Ruggiero R. Potential utilization of glycerol as crosslinker in starch films for application in Regenerative Dentistry. Res Soc Dev. 2021 Dec 12;10(16):e148101623640–e148101623640. [CrossRef]

- Mota J, Yu N, Caridade SG, Luz GM, Gomes ME, Reis RL, et al. Chitosan/bioactive glass nanoparticle composite membranes for periodontal regeneration. Acta Biomaterialia. 2012;8(11):4173–80. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Li HC, You TT, Wu YY, Ramaswamy S, Xu F. Fabrication of regenerated cellulose membranes with high tensile strength and antibacterial property via surface amination. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;140:111603. [CrossRef]

- Sousa BGB de, Pedrotti G, Sponchiado AP, Cunali RS, Aragones Á, Sarot JR, et al. Analysis of tensile strength of poly(lactic-coglycolic acid) (PLGA) membranes used for guided tissue regeneration. RSBO Online. 2014 Mar;11(1):59–65. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Zhang W, Wang Z, Wang Z, Xie Q, Niu H, Guo H, Yuan Y, Liu C. PEGylated poly(glycerol sebacate)-modified calcium phosphate scaffolds with desirable mechanical behavior and enhanced osteogenic capacity. Acta Biomaterialia. 2016;44:110–24. [CrossRef]

- Wong SC, Baji A, Leng S. Effect of fiber diameter on tensile properties of electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone). Polymer. 2008;49:4713–22. [CrossRef]

- Conte AA, Sun K, Hu X, Beachley VZ. Effects of Fiber Density and Strain Rate on the Mechanical Properties of Electrospun Polycaprolactone Nanofiber Mats. Front Chem. 2020;8:610. [CrossRef]

- Saravanan N, Yamunadevi V, Mohanavel V, Chinnaiyan VK, Bharani M, Ganeshan P, et al. Effects of the interfacial bonding behavior on the mechanical properties of E-Glass Fiber/Nanographite reinforced hybrid composites. Advances in Polymer Technology. 2021;2021:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Yusof MR, Shamsudin R, Zakaria S, Abdul Hamid MA, Yalcinkaya F, Abdullah Y, Yacob N. Fabrication and Characterization of Carboxymethyl Starch/Poly(l-Lactide) Acid/β-Tricalcium Phosphate Composite Nanofibers via Electrospinning. Polymers (Basel). 2019;11(9):1468. [CrossRef]

- Keikhaei S, Mohammadalizadeh Z, Karbasi S, Salimi A. Evaluation of the effects of β-tricalcium phosphate on physical, mechanical and biological properties of Poly (3-hydroxybutyrate)/chitosan electrospun scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering applications. Mater Technol. 2019;34(10):615–25. [CrossRef]

- Gosens I, Post JA, de la Fonteyne LJ, Jansen EH, Geus JW, Cassee FR, de Jong WH. Impact of agglomeration state of nano- and submicron sized gold particles on pulmonary inflammation. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010 Dec 2;7(1):37. [CrossRef]

- Dong X, Cheng Q, Long Y, Xu C, Fang H, Chen Y, Dai H. A chitosan based scaffold with enhanced mechanical and biocompatible performance for biomedical applications. Polym Degrad Stab. 2020;181:109322. [CrossRef]

- Wong SC, Baji A, Leng S. Effect of fiber diameter on tensile properties of electrospun poly(ɛ-caprolactone). Polymer. 2008;49(21):4713–22. [CrossRef]

- Tarus BK, Mwasiagi JI, Fadel N, Al-Oufy A, Elmessiry M. Electrospun cellulose acetate and poly(vinyl chloride) nanofiber mats containing silver nanoparticles for antifungi packaging. SN Applied Sciences. 2019;1(3):245. [CrossRef]

- Farias, J. R. S, Rocha G M, Carvalho G K G, Pereira G G S, Silva P F, Martins M M, Simões V N et. al. "Beta tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP): A scientific and technological mapping.”American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER), vol. 11(06), 2022, pp. 125-138.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).