Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivations

- resource constraints on the Galaxy server hosting the analysis may limit data uploading speed, available storage space, and/or computational capacity, potentially slowing down workflows during periods of high usage;

- the availability of dozens of tools for similar tasks (e.g., multiple aligners, trimmers, and differential expression packages) can be overwhelming—particularly for users who prefer a more streamlined and minimal environment;

- tool selection is not guided and terminology (e.g., GTF vs GFF3, strandedness, normalization methods) assumes bioinformatics background;

- the interface, while point-and-click, becomes dense and overwhelming quickly;

- as a result, despite its apparent simplicity, gaining proficiency in Galaxy’s internal logic (histories, datasets, job statuses, and parameter settings) can require a significant learning curve;

- on the other hand, for experienced users, Galaxy can feel less transparent, flexible, and customizable than command-line alternatives;

- integrating Galaxy tools into custom command-line pipelines can also be challenging;

- error reporting is often opaque, especially for tools that rely on complex stacks of dependencies and configurations.

1.2. Key Features

- Remote operability

- Standardization

- Simplification

- Automation

- Completeness

- No bioinformatics skills required

- Reproducibility

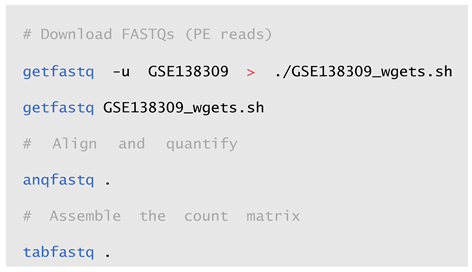

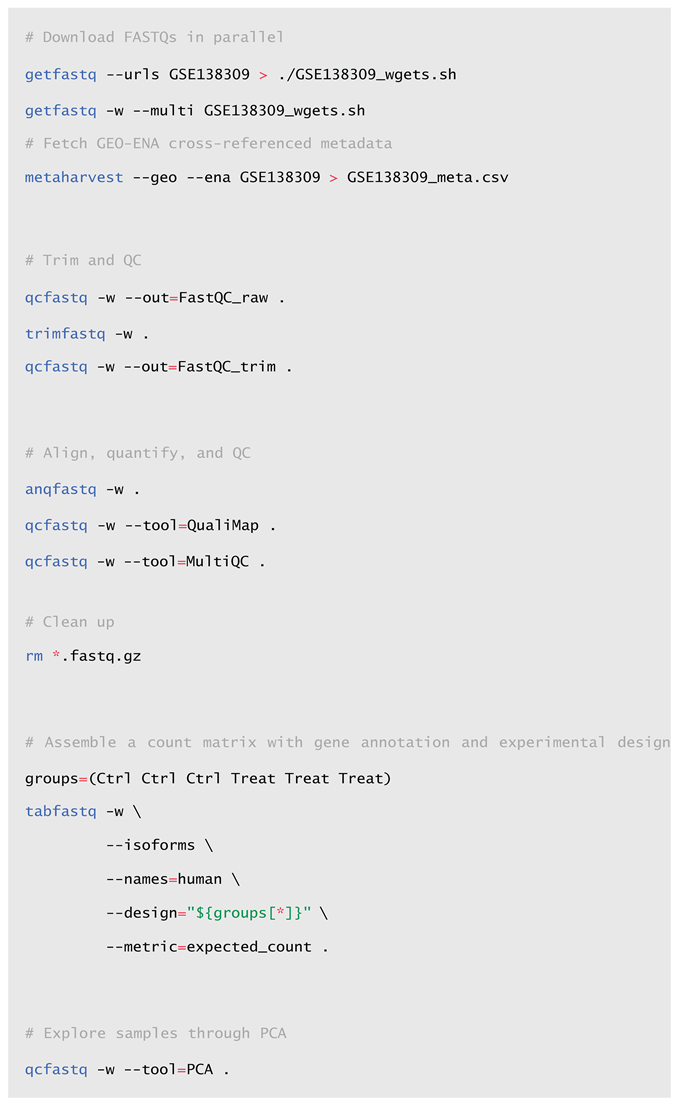

2. From Reads to Counts

2.1. x.FASTQ Modules

- getFASTQ allows the user to download NGS raw data in FASTQ format from the ENA database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home) to the machine hosting x.FASTQ;

- trimFASTQ uses BBDuk, from the BBTools suite [10] (https://archive.jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/software-tools/bbtools/), to remove adapter sequences and perform quality trimming;

- anqFASTQ uses STAR [3] (https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR) and RSEM [4] (https://github.com/deweylab/RSEM) to align reads and quantify transcript abundance, respectively, supporting both gene-level and isoform-level analyses;

- qcFASTQ is an interface for multiple quality-control tools, including FastQC [9] (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/), MultiQC [11] (https:// multiqc.info/), and PCA analysis;

- tabFASTQ merges counts from multiple samples into a single TSV expression table, choosing among multiple metrics (TPM, FPKM, RSEM expected counts) and levels (gene or isoform). Optionally, it inserts experimental design information into the matrix header and appends annotations regarding gene symbol, gene name, and gene type (Ensembl gene/transcript IDs are required for annotation);

- metaharvest fetches Sample and Study metadata from GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and/or ENA (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home) databases, then it parses the retrieved metadata and saves a local copy of them as a CSV-formatted table;

- x.FASTQ is a cover-script that performs a number of common tasks of general utility, such as dependency checking, symlink creation, version monitoring, and disk usage reporting.

- x.funx.sh contains variables and functions that must be shared (i.e., sourced) by all other x.FASTQ modules;

- progress_funx.sh collects all the functions for tracking the progress of the different modules (see the -p option below);

- trimmer.sh is the actual BBDuk wrapper, called by trimFASTQ;

- starsem.sh is the actual STAR/RSEM wrapper, called by trimFASTQ;

- assembler.R implements the matrix assembly procedure required by tabFASTQ;

- pca_hc.R implements Principal Component Analysis and Hierarchical Clustering of samples as required by the qcfastq --tool=PCA ... option;

- fuse_csv.R is called by metaharvest to merge the cross-referenced metadata down- loaded from both GEO and ENA databases;

- parse_series.R is called by metaharvest to extract metadata from a GEO-retrieved SOFT formatted family file;

- re_uniq.py is used to reduce redundancy when STAR and RSEM logs are displayed in the console as anqFASTQ progress reports.

- upon running x.fastq.sh -l <target_path> from the local x.FASTQ repository directory, each x.FASTQ module can be invoked from any location on the remote machine using its fully lowercase name (provided that <target_path> is already included in $PATH);

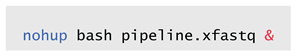

- by default, each script launches in the background a persistent job (or a queue of jobs) by using a custom re-implementation of the nohup command (namely the _hold_on function from x.funx.sh);

- each module (except x.FASTQ and metaharvest) saves its own log file inside the project directory using the filename pattern

-

some common flags keep the same meaning across all modules (even if not all of them are always available):

- ‣

- -h | --help to display the script-specific help;

- ‣

- -v | --version to display the script-specific version;

- ‣

- -q | --quiet to run the script silently;

- ‣

- -w | --workflow to make processes run in the foreground, useful when used in pipelines;

- ‣

- -p | --progress to see the progress of possibly ongoing processes;

- ‣

- -k | --kill to gracefully terminate possibly ongoing processes;

- ‣

- -a | --keep-all not to delete intermediate files upon script execution;

- all core modules are versioned according to the three-number Semantic Versioning system (https://semver.org/). x.fastq -r can be used to get a version report of all scripts along with the summary version of the whole x.FASTQ suite;

- if -p is followed by no other arguments, the script will search the current directory for log files from which to infer the progress of the last namesake task;

- with the -q option, scripts do not print anything to the screen except for possible error messages that stop execution (i.e., fatal errors); however, logging is never disabled.

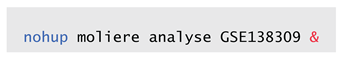

2.2. Usage and Workflow Examples

2.3. Installation and Deployment

2.4. Practical Considerations and Advanced Hints

- Adapter trimming: adapters are automatically detected based on BBDuk’s adapters.fa database and then right-trimmed using 23-to-11 base-long kmers allowing for one mismatch (i.e., Hamming distance =1). See the KTrimmed stat in the log file.

- Quality trimming: it is performed on both sides of each read using a quality score threshold trimq=10. See the QTrimmed stat in the log file.

- Length filtering: all reads shorter than 25 bases are discarded. See the Total Removed stat in the log file.

3. Conclusions

4. Software Availability

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. File Naming

Appendix A.2. Dependencies

| • Development Environments | https://www.java.com/ |

| ► Java | https://www.python.org/ |

| ► Python | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| ► R | https://www.bioconductor.org/ |

| ► Bioconductor Packages | |

| - BiocManager | |

| - PCAtools | |

| - org.Hs.eg.db | |

| - org.Mm.eg.db | |

| ► CRAN Packages | https://cran.r-project.org/ |

| - gtools | |

| - stringi | |

| • Linux Tools | |

| ► hostname | |

| ► jq | https://jqlang.org/ |

| ► figlet (optional) | |

| • QC Tools | |

| ► FastQC | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ |

| ► MultiQC | https://seqera.io/multiqc/ |

| ► QualiMap | http://qualimap.conesalab.org/ |

| • NGS Software | |

| ► BBDuk | https://archive.jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/software-tools/bbtools/ |

| ► STAR | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

| ► RSEM | https://github.com/deweylab/RSEM |

References

- Conesa, A.; et al. A survey of best practices for RNA-seq data analysis. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, R. , Duggal, G., Love, M.I., Irizarry, R.A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B. & Dewey, C.N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I. , Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, N.; et al. Reproducible bioinformatics project: a community for reproducible bioinformatics analysis pipelines. BMC Bioinformatics 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccuti, M.; et al. SeqBox: RNAseq/ChIPseq reproducible analysis on a consumer game computer. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 871–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afgan, E.; et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W3–W10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S.; et al. Babraham Bioinformatics - FastQC: A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. (2012). at https://www.bioinformatics.babraham. ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Bushnell, B. , Rood, J. & Singer, E. BBMerge – Accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e185056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P. , Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinform. (Oxf. Engl. ) 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandve, G.K. , Nekrutenko, A., Taylor, J. & Hovig, E. Ten Simple Rules for Reproducible Computational Research. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9, e1003285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, M. , Karsch-Mizrachi, I. & Cochrane, G. The international nucleotide sequence database collaboration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D121–D124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.R. , Baccarella, A., Parrish, J.Z. & Kim, C.C. Trimming of sequence reads alters RNA-Seq gene expression estimates. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).